Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Edilson Silva.

Os lagos de terras altas (ULs) em Carajás, sudeste da Amazônia, têm sido extensivamente estudados no que diz respeito à sua geologia estrutural de alta resolução, geomorfologia, estratigrafia, geoquímica de multielementos e isótopos, palinologia e limnologia.

The upland lakes (ULs) in Carajás, southeastern Amazonia, have been extensively studied with respect to their high-resolution structural geology, geomorphology, stratigraphy, multielement and isotope geochemistry, palynology and limnology.

- upland lakes

- Carajás mountain range

- landscape evolution

1. Introduçãction

Os

The uplagos de terras altand lakes (ULs) na Amazônia brasileira são formas de relevoin the Brazilian Amazon are singulares de média a mid-altitude (defrom 400 m ato 800 m) formadas sobre crostas lateríticas de ferro e ferrolandforms formed over iron and iron-aluminosas comous lateritic crusts as a resultado de processos tectônicos cíclicos, intemperismo of cyclic tectonic, weathering and the erosão em condições climáticas tropicaiional processes under tropical climate conditions [1,2,3][1][2][3]. EThestes lagos sãoe lakes are classificados como sistemas lacustres ativos e inativos,ed as active and inactive lake systems, the latter correspondendo este último a pântanos de terras altaing to upland swamps [4].

A d

Theposição de sedimentos em ULs é altamente deposition in ULs is highly influenciada pelas ced by the natural and local characterísticas naturais e locais da bacia hidrográficaistics of the catchment basin, incluindo ading the geologia, a cobertura vegetal, ay, vegetation cover, primary produtividade primária da bacia cctivity of the central [5,6,7]basin e[5][6][7] a indade relativa do lagoe lake age [3]. ADespesar daite the relativae homogeneidade, as bacias hidrográficas do sudeste amazônico apresentamty, the drainage basins in southeastern Amazonia localmente vários litotipos e cenáriosly present various lithotypes and geomorfológicophological settings. Consequentemente, eles mantêm comunidades vegetais com dily, they hold plant communities with differentes estruturas e structures and composiçõetions [8]. Além dissMo, os processosreover, diagenéticos etic processes have modificaram a composição dosed sedimentos composition [5]. TAll odos esses fatores têmf these factors have controlado as características geoquímicas eled the geochemical and limnológicas desses MSs ao longo do tempoogical characteristics of these ULs over time [9,10][9][10].

Os d

Thepósitos qQuaternários em ULs amazônicos têm espessuras diary deposits in Amazonian ULs have differentes. Alguns apresentam thicknesses. Some display continuous sedimentação contínua, comotion, as evidenciado nas serras de ed in the Seis Lagos (noroeste da Amazôthwestern Amazonia), Maicuru/Maraconaí (centro-nordeste da Amazônia) eal-northeastern Amazonia) and Carajás (sudeste da Amazônia) [4,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]outheastern Amazonia) mountain ranges [4][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]. AsThe investigações realizadas nessastions conducted at these localidades permitiram avaliar os efeitos dos últimos períodosties have allowed an evaluation of the effects of the last glacial eand interglacial na Amazôniaperiods on tropical. Os ULs podem se tornar mais semelhantes aos Amazonia. ULs may become more similar to terrestrial habitats terrestres durante o período during the negativo dee water balanço hídricoce period produzido pelo eced by prolonged water stresse hídrico prolongado, o que pode afetar os atributos ecológicos da biota , which may affect the ecological attributes of water-dependente d biota água [19,20][19][20]. EmIn contraste, ULs mais, more resilientes podem atuar como microrrefúgios para esses ULs may act as microrefuges for such organismos. Assim, tanto os aspectos físicos quanto biológicos, bem como sua natureza dinâmica, devem ser cuidadosamente avaliados em escalas de tempo mais curtas (anuais as. Thus, both the physical and biological aspects, as well as their dynamic nature, must be carefully evaluated over shorter (annual to decadais) e mais longas (século a milenar)l) and longer (century to millennial) time scales.

Geologiay, FiPhysiografia e phy and Climate

A árThea de estudo está localizada na porção leste da Província de study area is located in the eastern portion of Carajás, sudeste da Amazô Province, southeastern Amazonia (Figura 1e 1), and the a geologia é y is representada pored by: (1) sériesMesoarchean tonalita-e–trondhjemita-e–granodiorito mesoarqueanoe (TTG) e unidadesseries and granulíticas (Ortogranulito itic units (Xikrin-Cateté Orthogranulite) [36,37][21][22]; (2) SNequênciasoarchean metavuolcano-sedimentares neoarqueanay sequences [38][23]; (3) RNeochasarchean intrusivas neoarqueanas [39] e coe rposcks [24] estratificados máfico-nd mafic–ultramáficoafic stratified bodies [40][25]; (4) RPaleoproterozochasic sedimentarey rocks p[26]; and (5) Paleoproterozoicas [41]; e (5) intrusões anorogêenicas paleoproterozoica intrusions [42][27].

Figurae 1. MaUpa superior com área de estudo noper map with study area in the contexto da América do Sul e Floresta Amazônica (área verde: cobertura florestal, áreas vermelh of South America and Amazon Rainforest (green area: forest cover, red areas: desmatamento). Mapa inferior com legendasforestation). Lower map with associadas: mapa geológico mostrando as principais unidades litológicas da cordilheira de ted legends: geological map showing the main lithological units of the Carajás, na Amazônia brasileira. Os lagos estudados estão localizados nas crostas mountain range in the Brazilian Amazon. The studied lakes are located in the lateríticas doitic crusts in the Sul (lagos ativoactive lakes: Três Irmãs, Amendoim, Violão; lagos cheiofilled lakes: R1, R2, R4, R5), Norte (lago cheiofilled lake: Trilha da mata), Leste (lago ativoactive lake: lagoa Serra Leste – —LSL), Tarzan (lago ativoactive lake: Tarzan) eand Bocaína (lagos cheiofilled lakes: LB3, LB4); Província de Carajás (RM + S-CC + CB: Rio Maria + Sapucaia + domínios Canaã dos Carajás + Bacia do Carajás) plateaus.

2. ProcLakessos de Formação do Lago

AsFormation Processes

The crostas lateríticas da cordilheira do Sul são deslocadas por conjuntos de falhas E-W que são itic crusts of the Sul mountain range are displaced by sets of E–W faults that are responsáveis pela morfologia dos planaltos, falhas normais NW-SE para fraturas NE-SW e falhasible for the morphology of the plateaus, NW–SE normal faults to NE–SW fractures, and sinistral-normai—normal faults [3]. AThe partial dissolução parcial da crostation of the lateríticaitic crust orientada por essas fraturas e falhaed by these fractures and faults formou características cársticas, como cavernas, sumidouros e córregos subterrâneoed karst-like features, such as caves, sinkholes and underground streams [1]. UmaA série de reativações de falhas promoveu o colapso de blocos ao longo das falhaseries of fault reactivations promoted the collapse of blocks along the normais, que formaram os lagos rasos de terras altas. A dissolução parcial dal faults, which formed the shallow upland lakes.

The crosta laterítica e o escoamento intenso, particularmente durante a estação chuvosa, favorecem o transporte e a deposição de sedimentos clásticos no lago [44]. Em hallow-water seismic transects and their reflection charalguncteris casos, a sobrecarga da base dos lagos, juntamente com reativações de falhas, promoveu novos colapsos e aumentou o espaço de acomodação dos lagos [44].

Os transtics, as well as the sediment cores, allowectosd sísmicos em águas rasas e suas características de reflexão, bem como os núcleos sedimentares, permitiramresearchers to identificar ay the geometria das unidades sy of the seismostratigráficaaphic units depositadas nas ULs ded in the Carajás [3]ULs [3] (Figurae 2). AsThe características acústicas estãoacoustic features are associadas à morfometria e morfologia doted with the morphometry and morphology of the bedrock refletor do leito rochoso, fluxos de detritos, estruturasctor, debris flows, synsedimentary deformacionais sinsedimentares, refletores planotional structures, plane-paralelos e múltiploslel reflectors and multiple refletores da interface águactors from the water-substratoe interface (Figurae 2). AThe interface entre osbetween the bottom sedimentos de fundo e a crosta laterítica é marcada por umas and the lateritic crust is marked by a total acoustic reflexão acústica total da crosta, quection of the crust, which produz múltiplos de fundo de lago de forte amplitude (refletores de rocha). Os depósitos basais de grão fino localizados perto das principais entradas de drenagemces strong-amplitude lake-bottom multiples (bedrock reflectors). The basal fine-grained deposits located near the main drainage inflows correspondem aos clinoformes de to the fault-collapsed, basinward progradação em direção à bacia colapsados por falhaing clinoforms relacionados aos ventiladorested to the delta. Os fans. Underflow processos de subfluxo são es are responsáveis pelo transporte de partículas de grão fino em direção ao ible for carrying fine-grained particles toward the lake depocentro do lagoer, interrompidas por leitos supted by siderite. Os depósitos superiores estão relacionados à lama maciça beds. The top deposits are related to massive aggradactional e sem estrutura com algunsand structureless mud with some scattered peat fragmentos de turfa dispersos s (Figurae 2). IsThiso cria um arranjo que facies an arrangement that produz ciclos ascendentes de aletamento e desbaste, que podem variar em espessuraces fining and thinning upward cycles, which might vary in thickness dependendo da taxa do espaço de acomodaçãoing on the rate of the accommodation space.

Figurae 2. TransectosNW–SE sísmicos longitudinais NW-SE mostrando os diferentes níveis morfológicos observados, unidades deposicionais, refletores basais e múltiplos e falha. A interpretação sl seismic transects showing the different observed morphologic levels, depositional units, basement and multiple reflectors, and fault. The seismostratigráfica na parte inferior da figura. Figura superior (imagem sísmica rasa), figura média (interpretação saphic interpretation in the lower part of the figure. Upper figure (shallow seismic image), middle figure (seismostratigráfica) eaphic interpretation) and lower figura inferiore (legendas e localização do perfil sísmico na batimetria do lagos and location of the seismic profile in the lake bathymetry).

3. Surface Geologia de Superfície e y and Geobotânica das Bacias Hidrográficaany of the Catchment Basins

AsThe crostas lateríticas da área de estudo sãoitic crusts of the study area are geneticamentelly classificadas como crostas estruturadas (minério de ferroed as structured (iron ore), detríticas e ricaital and Al-rich crusts em[28] Al [48] (Figurae 3). Crostas esStruturadas e detríticas foram formadas pelactured and detrital crusts were formed by the lateritização do BIF e pelo intemperismo das crostas estruturadation of BIF and the weathering of the structured crusts, respectivamente, e contêmely, and contain hematitae, magnetitae, goethita e, secundariamente, minerais de e and secondarily quartzo e argila and clay minerals [9]. EThessas crostas são geralmente espessas e mais e crusts are generally thick and more resistentes ao intemperismo modernoant to modern weathering, formando apenas ping only Petric Plinthossolos petrânicos/aols/Petroferric Acrustox petroférricos, que , which dominam os níveiste the higher topográficos mais altos. Por outro lado, as crostas ricas em Al formadas pelaaphic levels. Conversely, the Al-rich crusts formed by the lateritização de rochas máficas são mais ricas em minerais argilosos e tion of mafic rocks are richer in clay minerals and gibbsitae, especialmente perto do horizontlly close to the saprólito. Além disso, são menoolite horizon. Additionally, they are less resistentes ao intemperismo e ocorrem em cotas mais baixas do que crostas estruturadas e detríticas. Assim, essas crostas podemant to weathering and occur on lower quotas than structured and detrital crusts. Thus, these crusts may produzir solos mais espessos (ou sejace thicker soils (i.e., Ferrasols/LatossoloOxisols).

The detrital and structured crusts have some peculiar characteristics, including shallow, patchy and acidic soils, with low water retention and nutrient availability and high insolation and temperature [49[30][31],50], which allowed the widespread development of canga vegetation and hindered the colonization of tree species (Figure 3a–d), such as SDF and HETF [8,49][8][30]. This interpretation is supported by the high δ13C values of the canga vegetation compared to soils in neotropical forests, which are related to more pronounced water shortages in cangas than forests [51][32]. Mafic sills and dikes are predominant on the slopes of the Carajás mountain range and marginal to the Três Irmãs and Violão lakes, extending toward Amendoim Lake (Figure 3a–d). Palms and macrophytes occur extensively in filled lakes (Figure 3e–h). Moreover, macrophytes, especially Isoëtes cangae, which is a very rare and endemic species, are widely found at the bottom of Amendoim Lake at depths up to 7 m [52][33]. The dominant plant species of each physiognomy are described in Table 1.

The detrital and structured crusts have some peculiar characteristics, including shallow, patchy and acidic soils, with low water retention and nutrient availability and high insolation and temperature [49[30][31],50], which allowed the widespread development of canga vegetation and hindered the colonization of tree species (Figure 3a–d), such as SDF and HETF [8,49][8][30]. This interpretation is supported by the high δ13C values of the canga vegetation compared to soils in neotropical forests, which are related to more pronounced water shortages in cangas than forests [51][32]. Mafic sills and dikes are predominant on the slopes of the Carajás mountain range and marginal to the Três Irmãs and Violão lakes, extending toward Amendoim Lake (Figure 3a–d). Palms and macrophytes occur extensively in filled lakes (Figure 3e–h). Moreover, macrophytes, especially Isoëtes cangae, which is a very rare and endemic species, are widely found at the bottom of Amendoim Lake at depths up to 7 m [52][33]. The dominant plant species of each physiognomy are described in Table 1.

Figure 3. (a,b) Digital elevation model (DEM) integrated with bathymetric data showing the western and eastern portions of the Serra Sul Plateau and the main lithotypes described in the catchment basins of active ULs. Aerial photograph of (c) Três Irmãs (TI1, TI2 and TI3), (d) Amendoim (AM) and Violão lakes (VL). (e,f) DEM showing the main lithotypes described in the catchment basins of filled ULs, also a detail (black arrow) for the direction of view of photo (e,f). (g,h) Aerial photograph of the filled ULs.

Table 1. Main plant species of canga vegetation, SDF (semideciduous tropical dry forests) HETF (humid evergreen tropical forest) and filled lakes according to their based on [9[9][34],30], reviewed according to Carajás Flora Project [53][35].

| Vegetation Type | Species | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canga | Dyckia duckei | (Bromeliaceae), | Ipomoea marabensis | (Convolvulaceae), | Erythroxylum nelson-rosae | (Erythroxylaceae), | Bauhinia pulchella | , | Mimosa acutistipula var. ferrea | and | M. skinneri var. carajarum | (Fabaceae), | Byrsonima chrysophylla | (Malpighiaceae), | Norantea goyasensis | (Marcgraviaceae), | Tibouchina edmundoi | and | Pleroma carajasensis | (Melastomataceae), | Sobralia liliastrum | (Orchidaceae), | Axonopus carajasensis | , | Panicum millegrana | , | Paspalum cangarum | , | P. carajasense | and | Sporobolus multiramosus | (Poaceae), | Borreria | (Rubiaceae), | Vellozia glauca | (Velloziaceae) | , Callisthene microphylla | (Vochysiaceae). |

| SDF | Licania blackii | (Chrysobalanaceae), | Aparisthmium cordatum | and | Maprounea guianensis | (Euphorbiaceae), | Myrcia splendens | (Myrtaceae), | Henriettea ramiflora | , | Miconia chrysophylla | (Melastomataceae), | Matayba inelegans | (Sapindaceae). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HETF | Tapirira guianensis | (Anacardiaceae), | Guatteria punctata | and | G | . | tomentosa | (Annonaceae), | Oenocarpus distichus | (Arecaceae), | Cordia sellowiana | (Boraginaceae), | Licania laxiflora | (Chrysobalanaceae), | Deguelia negrensis | , | Pseudopiptadenia suaveolens | (Fabaceae), | Emmotum nitens | (Icacinaceae), | Sacoglottis mattogrossensis | (Humiriaceae), | Mezilaurus itauba | (Lauraceae), | Miconia piperifolia | (Melastomataceae), | Myrcia silvatica | (Myrtaceae), | Neea ovalifolia | (Nyctaginaceae), | Matayba arborescens | (Sapindaceae), | Erisma uncinatum | (Vochysiaceae). | ||||

| Filled lakes | Mauritiella armata | (Arecaceae), | Eleocharis pedroviane | , | Cyperus, Scleria | (Cyperaceae), | Hydrochorea corymbosa | (Fabaceae), | Miconia alternans | (Melastomataceae), | Styrax griseus | (Styracaceae). |

4. Modern Sedimentation Patterns: Basin Morphology and Source-to-Sink Relationship

The active Carajás ULs have mid-altitude ranges (695–725 m), very small surface areas (<0.5 km2), shallow to very shallow depths (<10 m: mean depth) and catchments with relatively high declivities (>20° and maximum of ~60°) [21][36]. The Violão (VL) and Amendoim (AM) lakes are separated by an intermediate basin that prevents any surface connection of water between them (Figure 3b). The catchment of Amendoim Lake was composed of two lakes (Figure 3d), but the smaller lake, located in the western portion, was progressively filled by detritic and organic sediments and currently represents a filled lake (swamp) colonized by macrophytes [30][34]. In contrast, the three lakes (TI1, TI2 and TI3) of Três Irmãs are connected, and the water flow follows the elevation gradient from TI1 to TI3 (Figure 3c), forming a small waterfall between the lakes [21][36].

The statistical distribution of the major and trace elements in the lake sediments shows that there is considerable variation in the chemical elements among the lakes, which is reinforced by the Kruskal–Wallis test, which indicated p values of <0.05 for most of the elements. Si was the highest in VL and the lowest in TI2, which had the highest total organic carbon (TOC) values. The concentrations of Al, P, Ti and Zr are mainly enriched in TI1, followed by VL. This enrichment is due to the presence of Al-enriched lateritic crusts (including basalts) and soils. When compared to upper the continental crust (UCC) values, Fe is highly enriched in all of the lake sediments, followed by P and Se, while the concentrations of Na, K and Ca are highly depleted. The strong depletion of these mobile elements is due to intense chemical weathering in the source areas, which is an indication of a typical lateritic environment.

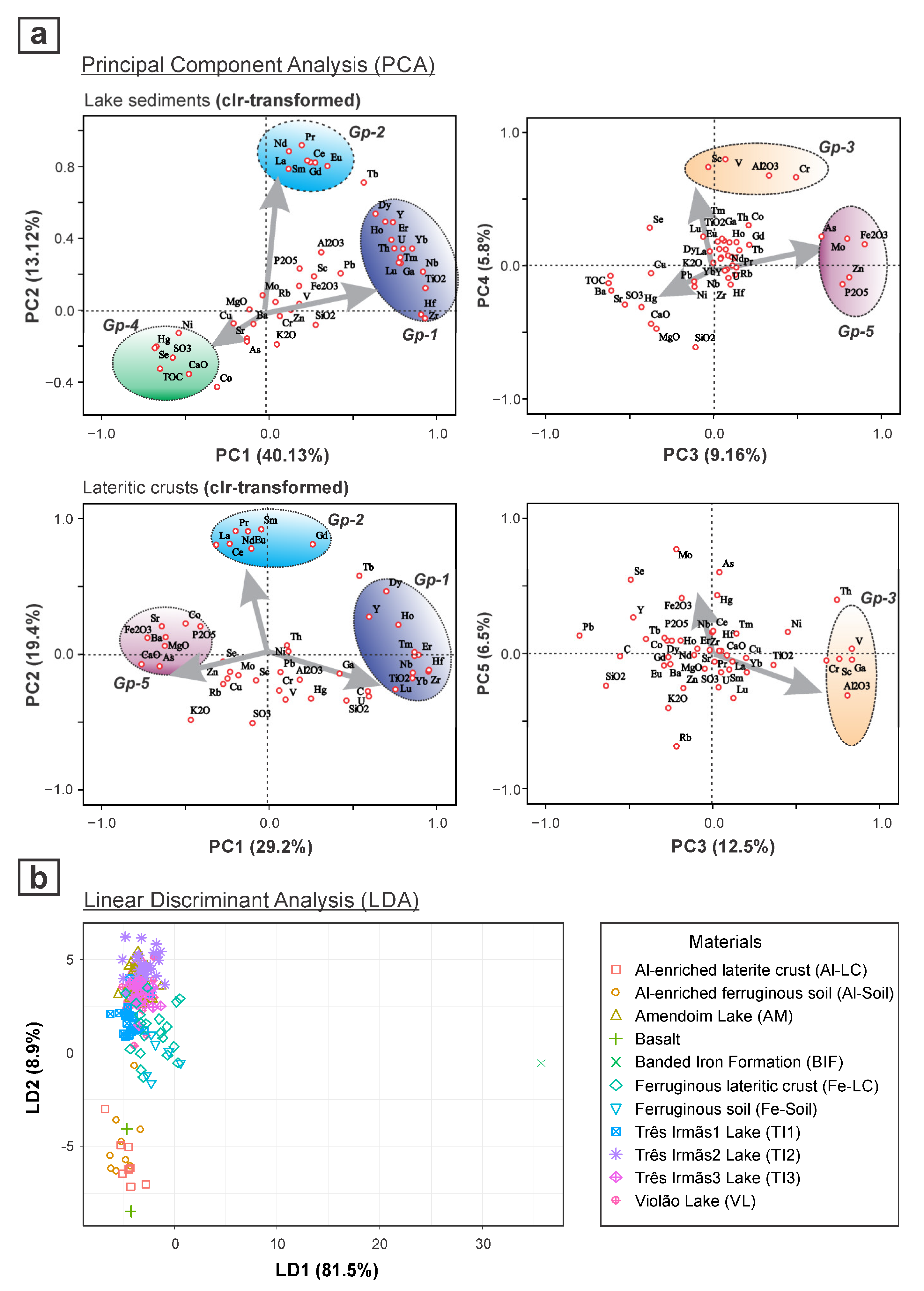

Integrating the geochemical data from active ULs, based on principal components analysis (PCA), five major groups of geochemical associations are distinguished (Figure 4a), with the major detritic groups being similar to the catchment basin laterites [25][29]. The Ti-Zr-Hf-Y-Nb-HREE (Gp-1) corresponds to resistant minerals, which possibly remained stable during lateritization, while the different behavior of the LREE (Gp-2) relative to the HREE indicates their relative mobility during laterite formation and reprecipitation by REE-bearing minerals. The Al-Sc-V-Cr association (Gp-3) in the sediments reflects the signature of the local country rock, such as mafic sills. TOC-SO3-Hg-Se (Gp-4) is controlled by organic matter, while the Fe-P-Mo-As-Zn (Gp-5) in the sediments is influenced by Fe-oxyhydroxide precipitation.

Figure 4. Principal component analysis (PCA) biplot of PC1 vs. PC2 and PC3 vs. PC4 for active lake sediments and catchment lateritic crusts, based on centered log-ratio (clr)-transformed data, showing the different geochemical associations and the major detrital signatures that are similar among them (a); and linear discriminate analysis (LDA) showing the distribution of lake sediments and the relationship with catchment basin materials (b).

The detritic association of Gps 1, 2 and 3, similar to the catchment rocks indicates a strong influence on the catchment basin lithology and laterization processes. The multivariate analysis, such as the linear discriminant analysis (LDA), further indicates that the detritic sediments are not directly derived from the parent rocks (Figure 4b), but are well correlated with the underlying weathered crusts (mainly ferruginous) and soils, while the ferruginous laterite crusts are the major source of detrital sediments. This inference demonstrates that lake sediments can be a potential tool for identifying and describing the catchment processes and basin lithology.

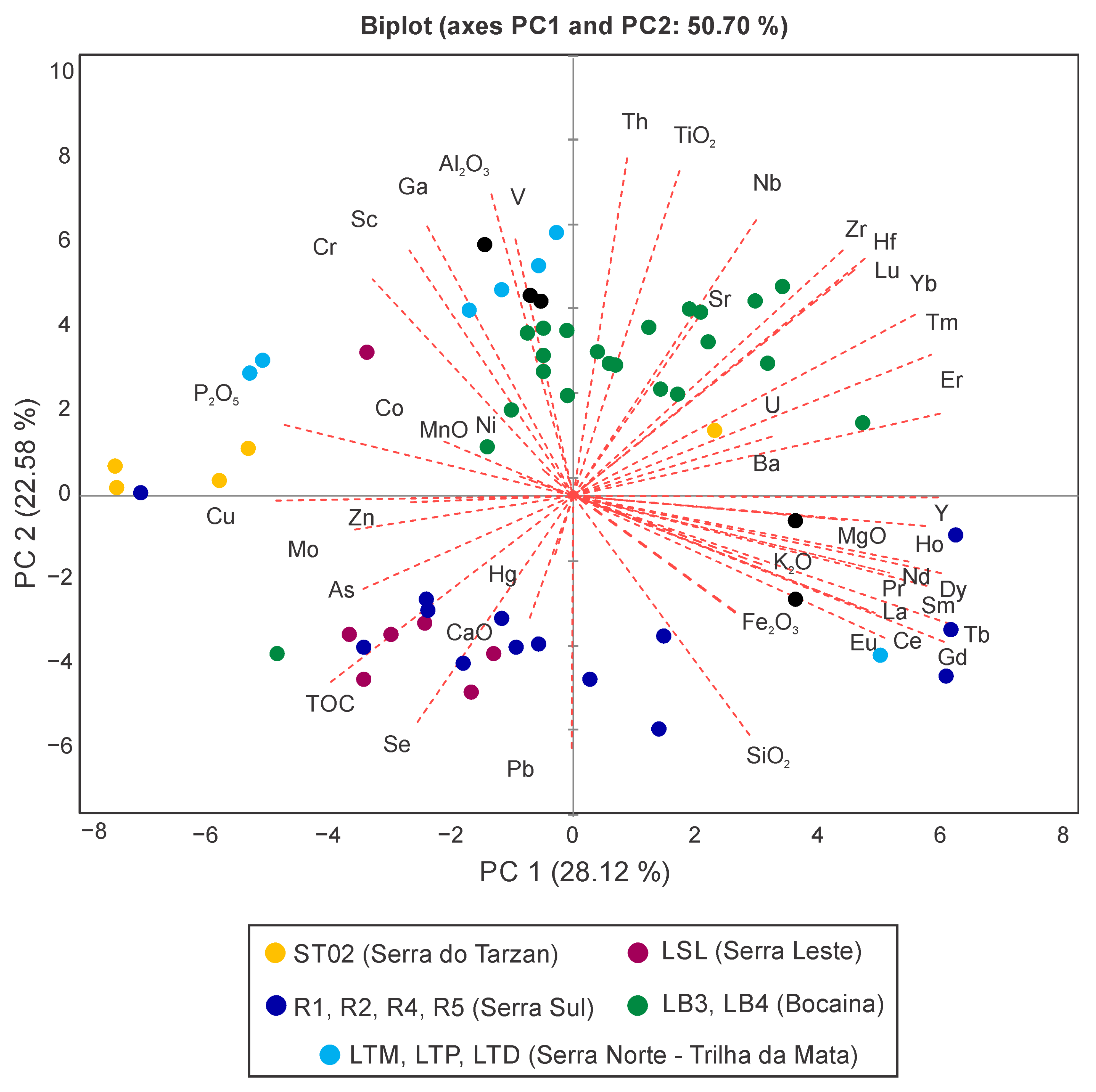

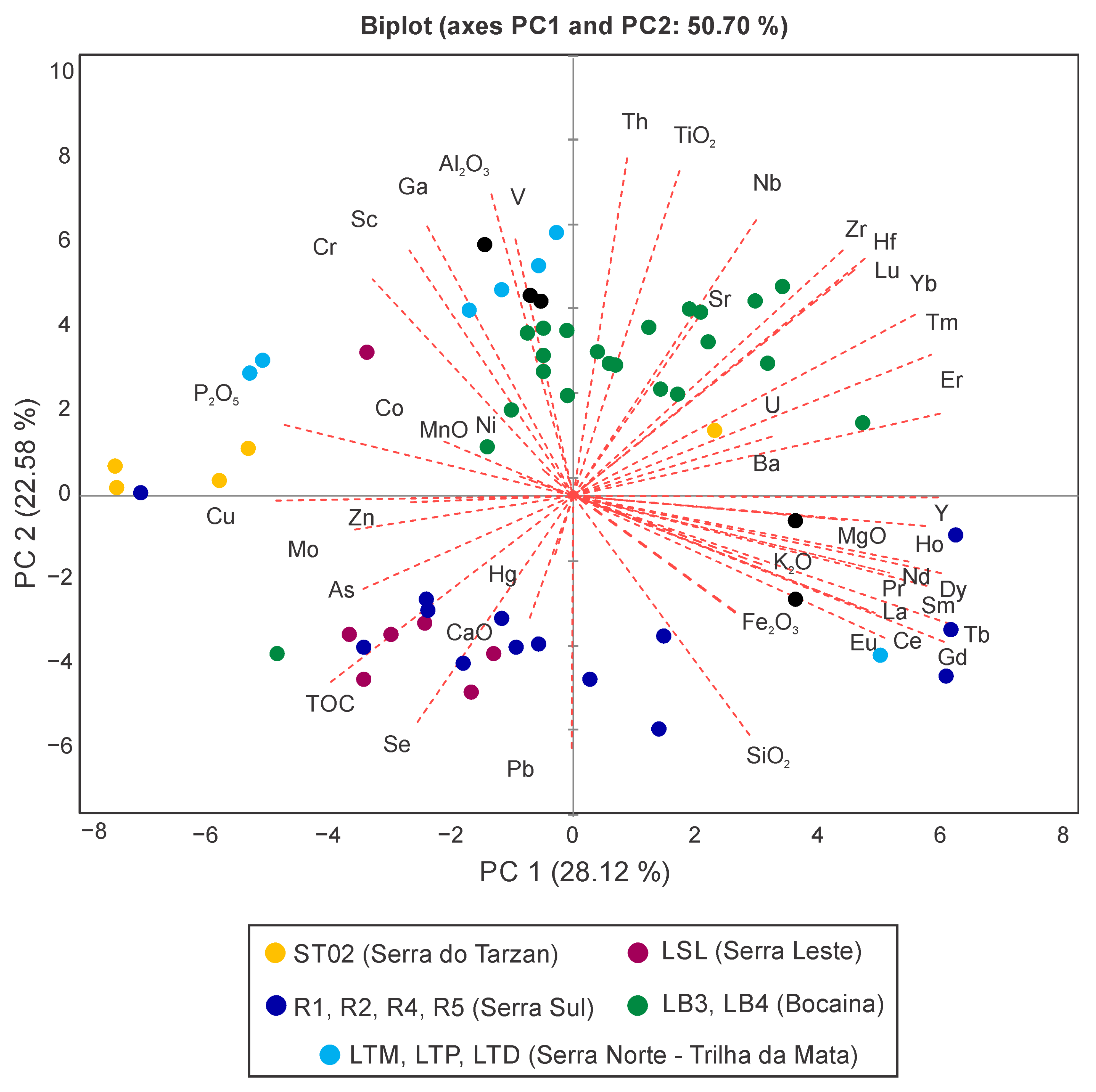

PCA performed on the centered log-ratio (clr)-transformed data was also employed to evaluate the relationships of the geochemistry of the bottom sediments among the filled lakes (Figure 5). The Bocaína (LB3 and LB4) lakes were mostly differentiated from the others as they loaded weakly positively on the PC2. This feature is related to the dominance in that area of Al-enriched lateritic crusts that were formed mostly from metavolcanic rocks. Thus, the geochemical signature of the Bocaína lake sediments shows higher concentrations of Al, Ga, Ti, Cr, V, Sc and REEs [24][37]. In these sediments, there is different geochemical behavior between the LREE and HREE, which is due to their different mobilities during lateralization [25][29]. Similar high enrichment of the detritic elements, such as Al, V, Ga and Cr, which are moderate to highly loaded on PC2, were also observed in the lakes from the Norte mountain range—Trilha da Mata Lake (LTM, LTP and LTD).

Figure 5. Principal component analysis (PCA) performed on centered log-ratio (clr)-transformed data for all filled lakes (sediment cores).

The sediments from Tarzan Lake (ST02) show mostly negative loading on PC1 and positive loading on PC2. This result is partly associated with Fe, suggesting that the crusts are similar to the Sul mountain range, but the high enrichment of Co, Cu, Mo, P, Cr and P in these sediments indicates a strong influence of mafic rocks, which is not exactly similar to that observed in the Bocaína lake sediments.

The sediments from Leste Lake (LSL) are negatively loaded on both PC1 and PC2 and seem very different from the sediments of the other lakes. The high enrichment of TOC in the detritic sediments of these lakes points to the control of different geomorphological and lithological characteristics of the basin. Moreover, in the Leste Lake sediments, As is more enriched, similar to the sediments from Tarzan lakes, suggesting the presence of sulfide minerals in the catchment rocks.

The filled lakes in the Sul mountain range (R1, R2, R4 and R5) have widely variable geochemical compositions, with the samples being positively and negatively loaded on PC1. Most of them are associated with Fe, as well as Si, thus indicating that the crusts developed mainly from iron formations, which have significant concentrations of Fe, while the Si contribution comes from BIF.

All of this fundamental knowledge of the modern lake sedimentary processes of Amazonian ULs and their catchment interactions can thus provide crucial insights for the interpretation of source—sink relationships and paleoclimate reconstruction.

5. Environmental Influences on Limnology and Water Quality

Regarding the ULs in the Carajás region, the lake waters are mostly acidic (avg. pH of 4.9–5.9), with high total Fe (up to 1.52 mg/L) and low SO42− and other metal concentrations [10]. The low pH can be explained by the trivial level of carbonate minerals and the total dominance of ferruginous lateritic material in the catchment, as well as high sedimentary organic carbon in the lake bottom, which releases CO2 and H2S via bacterial decomposition, making the water acidic [54][38]. The high levels of Fe in the lake water are related to the weathering and erosion of the catchment ferruginous soils and lateritic crusts. This evidence indicates that the catchment geology is the dominant factor influencing the lake water chemistry.

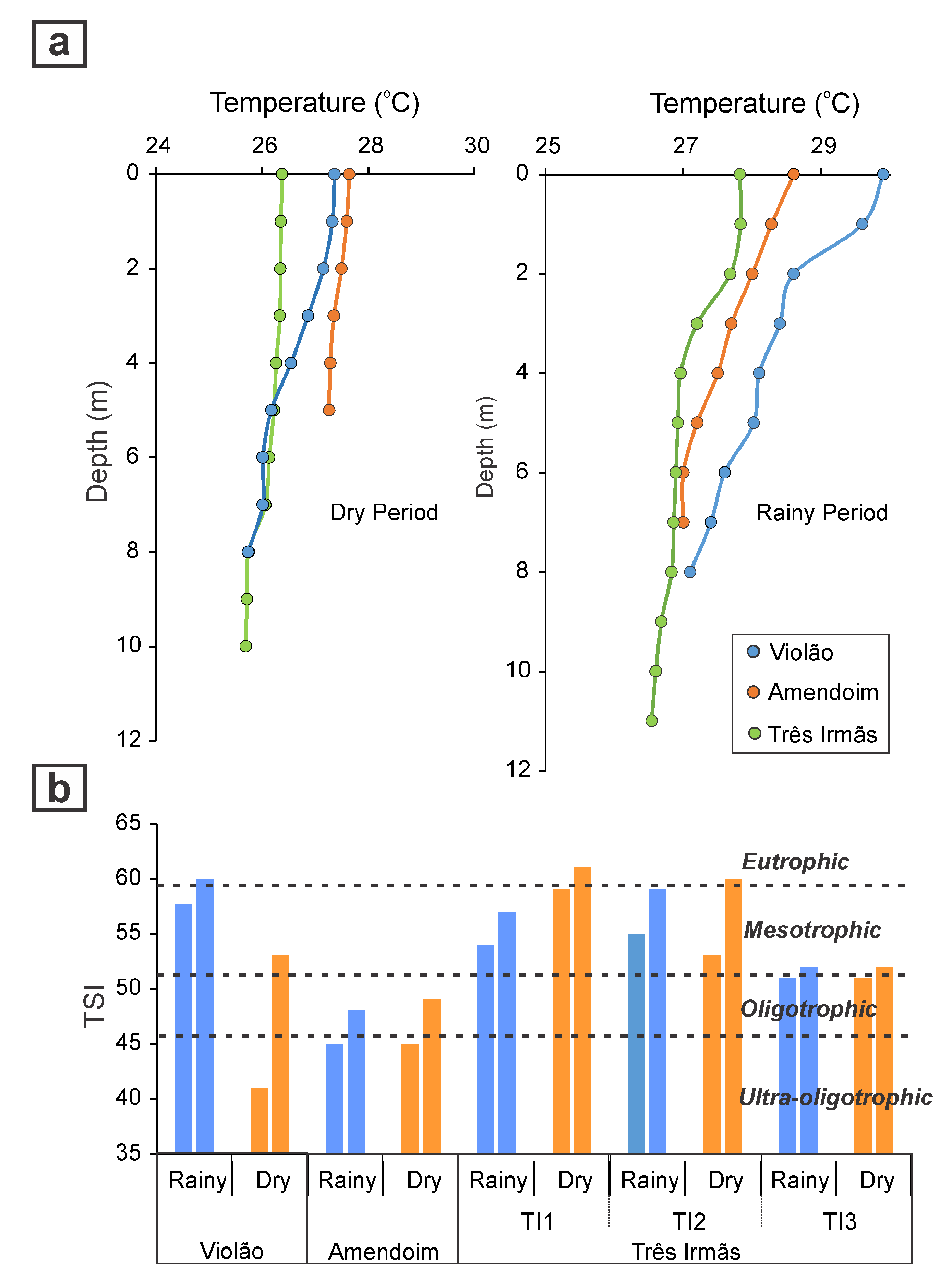

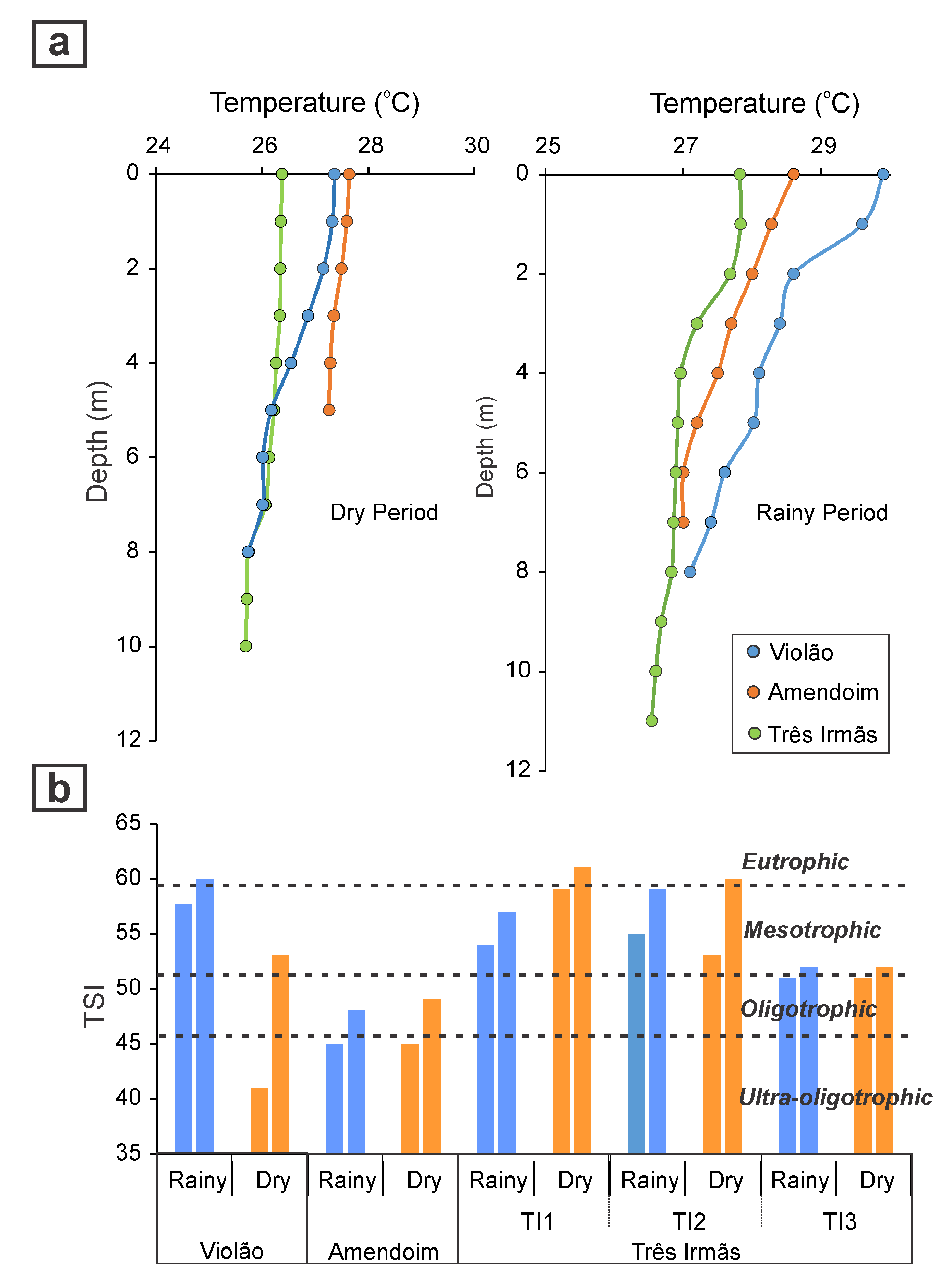

These ULs are shallow, weakly stratified (Figure 6a) and classified as polymictic, which controlled the vertical mixing of the limnological parameters [10]. Although the water quality index (WQI) shows good water quality and high similarity among the studied lakes, the trophic state of these lakes varied significantly between ultraoligotrophic and eutrophic (Figure 6b), with lower values observed for Amendoim Lake [10]. High trophic states are due to nutrient concentrations, mainly total phosphorous (TP), promoting algal growth. The sources of TP for these lakes are associated with the presence of mafic rocks and caves with high guano volume [7,10][7][10]. Although Chl-a and cyanobacteria are mainly influenced by nutrients such as TP, this is not the case for these lakes; rather, they are controlled by additional factors, such as the seasonal climate conditions, catchment lithology specificities and lake morphology [10].

Figure 6. Vertical temperature profile in Violão, Amendoim and Três Irmãs lakes during the dry and rainy seasons showing the thermal stratification of the lakes (a), and trophic state index (TSI) of the lakes during both dry and rainy seasons (b), showing the significant variation in trophic state among lakes.

The Phytoplankton taxa in the lakes are characterized by small Chroococcales groups and desmids, together with filamentous algae, which are more commonly observed in the dry season. The Phytoplankton composition also varies among the lakes based on the differences in the water depth and nutrient concentration [10]. The studies conducted thus far have contributed to understanding the common limnological characteristics of the Amazonian ULs and their role in controlling the geochemical distribution of the elements and diagenetic processes in the sediments.

References

- Maurity, C.W.; Kotschoubey, B. Evolução recente da cobertura de alteraçao no platô N1-Serra dos Carajás-PA: Degradação, pseudocarstificaçao, espeleotemas. Bol. Mus. Para. Emilio Goeldi. Ser. Ciênc. Terra 1995, 7, 331–362.

- Costa, M.L.; Carmo, M.S.; Behling, H. Mineralogia e geoquímica de sedimentos lacustres com substrato laterítico na Amazônia Brasileira. Rev. Bras. Geociências 2005, 35, 165–176.

- Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; Pinheiro, R.V.L.; Costa, F.R.; Guimarães, J.T.F.; Sahoo, P.K.; Silva, M.S.; Silva, C.G. The role of fault reactivation in the development of tropical montane lakes. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2020, 45, 3732–3746.

- Reis, L.S.; Guimarães, J.T.F.; Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; Sahoo, P.K.; Figueiredo, M.M.J.C.; Souza, E.B.; Giannini, T.C. Environmental and vegetation changes in southeastern Amazonia during the late Pleistocene and Holocene. Quat. Int. 2017, 449, 83–105.

- Sahoo, P.K.; Souza-Filho, P.W.; Guimarães, J.T.; Da Silva, M.S.; Costa, F.R.; De Oliveira Manes, C.L.; Oti, D.; Júnior, R.O.; Dall’Agnol, R. Use of multi-proxy approaches to determine the origin and depositional processes in modern lacustrine sediments: Carajás Plateau, Southeastern Amazon, Brazil. Appl. Geochem. 2015, 52, 130–146.

- Sahoo, P.K.; Guimaraes, J.T.; Souza-Filho, P.W.; da Silva, M.S.; Maurity, C.W.; Powell, M.A.; Rodrigues, T.M.; Da Silva, D.F.; Mardegan, S.F.; Neto, A.E.; et al. Geochemistry of upland lacustrine sediments from Serra dos Carajás, Southeastern Amazon, Brazil: Implication for catchment weathering, provenance, and sedimentary processes. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2016, 72, 178–190.

- Sahoo, P.K.; Guimarães, J.T.; Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; Da Silva, M.S.; Júnior, R.O.S.; Pessim, G.; De Moraes, B.C.; Pessoa, P.F.; Rodrigues, T.M.; Da Costa, M.F.; et al. Influence of seasonal variation on the hydro-biogeochemical characteristics of two upland lakes in the Southeastern Amazon, Brazil. An. Acad. Bras. Ciências 2016, 88, 2211–2227.

- Nunes, J.A.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R.; Ferreira Júnior, W.G.; Neri, A.V.; Correa, G.R.; Enright, N.J. Soil-vegetation relationships on a banded ironstone ‘island’, Carajás Plateau, Brazilian Eastern Amazonia. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2015, 87, 2097–2110.

- Sahoo, P.K.; Guimarães, J.T.; Souza-Filho, P.W.; da Silva, M.S.; Júnior, W.N.; Powell, M.A.; Reis, L.S.; Pessenda, L.C.; Rodrigues, T.M.; da Silva, D.F.; et al. Geochemical characterization of the largest upland lake of the Brazilian Amazonia: Impact of provenance processes. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2017, 80, 541–558.

- Sahoo, P.K.; Guimarães, J.T.; Souza-filho, P.W.; Bozelli, R.L.; de Araujo, L.R.; de Souza Menezes, R.; Lopes, P.M.; da Silva, M.S.; Rodrigues, T.M.; da Costa, M.F.; et al. Limnological characteristics planktonic diversity of five tropical upland lakes from Brazilian Amazon. Ann. Limnol. Int. J. Limnol. 2017, 53, 467–483.

- Colinvaux, P.A.; Irion, G.; Räsänen, M.E.; Bush, M.B.; Nunes de Mello, J.A.S. A paradigma to be discarded: Geological and paleoecological data falsify the HAFFER & PRANCE refuge hypothesis of Amazonian speciation. Amazoniana 2001, 16, 609–646.

- Bush, M.B.; Oliveira, P.E.; Colinvaux, P.A.; Miller, M.C.; Moreno, J.E. Amazonian palaeoecological histories: One hill three watersheds. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2004, 214, 359–393.

- Sifeddine, A.; Martin, L.; Turcq, B.; Volkmer-Ribeiro, C.; Soubiès, F.; Cordeiro, R.C.; Suguio, K. Variations of the Amazonian rainforest environment: A sedimentological record covering 30,000 years. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2001, 168, 221–235.

- Cordeiro, R.; Turcq, B.; Sifeddine, A.; Lacerda, L.; Filho, E.S.; Gueiros, B.; Potty, Y.; Santelli, R.; Pádua, E.; Patchinelam, S. Biogeochemical indicators of environmental changes from 50Ka to 10Ka in a humid region of the Brazilian Amazon. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2011, 299, 426–436.

- D’Apolito, C.; Absy, M.L.; Latrubesse, E.M. The Hill of Six Lakes revisited: New data and re-evaluation of a key Pleistocene Amazon site. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2013, 76, 140–155.

- Guimarães, J.T.F.; Sahoo, P.K.; Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; Maurity, C.W.; Silva, J.R.O.; Costa, F.R.; Dall’Agnol, R. Late Quaternary environmental climate changes registered in lacustrine sediments of the Serra Sul de Carajás southeast Amazonia. J. Quat. Sci. 2016, 31, 61–74.

- Guimarães, J.T.F.; Sahoo, P.K.; De Figueiredo, M.M.J.C.; Lopes, K.S.; Gastauer, M.; Ramos, S.J.; Caldeira, C.F.; Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; Reis, L.S.; Da Silva, M.S.; et al. Lake sedimentary processes and vegetation changes over the last 45k cal a BP in the uplands of south-eastern Amazonia. J. Quat. Sci. 2021, 36, 255–272.

- Reis, L.S.; Bouloubassi, I.; Mendez-Millan, M.; Guimarães, J.T.F.; Romeiro, L.D.A.; Sahoo, P.K.; Pessenda, L.C.R. Hydroclimate and vegetation changes in southeastern Amazonia over the past ∼25,000 years. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2022, 284, 107466.

- Lopes, P.M.; Caliman, A.; Carneiro, L.S.; Bini, L.M.; Esteves, F.A.; Farjalla, V.; Bozelli, R.L. Concordance among assemblages of upland Amazonian lakes and the structuring role of spatial and environmental factors. Ecol. Indic. 2011, 11, 1171–1176.

- Mormul, R.P.; Esteves, F.D.A.; Farjalla, V.F.; Bozelli, R.L. Space and seasonality effects on the aquatic macrophyte community of temporary Neotropical upland lakes. Aquat. Bot. 2015, 126, 54–59.

- Feio, G.; Dall’Agnol, R.; Dantas, E.; Macambira, M.; Santos, J.; Althoff, F.; Soares, J. Archean granitoid magmatism in the Canaã dos Carajás area: Implications for crustal evolution of the Carajás province, Amazonian craton, Brazil. Precambrian Res. 2013, 227, 157–185.

- Moreto, C.P.N.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Xavier, R.P.; Creaser, R.A.; DuFrane, S.A.; Tassinari, C.C.G.; Sato, K.; Kemp, A.I.S.; Amaral, W.S. Neoarchean and Paleoproterozoic Iron Oxide-Copper-Gold Events at the Sossego Deposit, Carajas Province, Brazil: Re-Os and U-Pb Geochronological Evidence. Econ. Geol. 2015, 110, 809–835.

- Martins, P.L.G.; Toledo, C.L.B.; Silva, A.M.S.; Chemale, F., Jr.; Santos, J.O.S.; Assis, L.M. Neoarchean magmatism in the southeastern Amazonian Craton, Brazil: Petrography, geochemistry and tectonic significance of basalts from the Carajás Basin. Precambrian Res. 2017, 302, 340–357.

- Dall’Agnol, R.; da Cunha, I.R.V.; Guimarães, F.V.; de Oliveira, D.C.; Teixeira, M.F.B.; Feio, G.R.L.; Lamarão, C.N. Mineralogy, geochemistry, and petrology of Neoarchean ferroan to magnesian granites of Carajás Province, Amazonian Craton: The origin of hydrated granites associated with charnockites. Lithos 2017, 277, 3–32.

- Mansur, E.T.; Filho, C.F.F.; Oliveira, D.P. The Luanga deposit, Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil: Different styles of PGE mineralization hosted in a medium-size layered intrusion. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 118, 103340.

- Nogueira, A.C.R.; Trunckenbrodt, W.; Pinheiro, R.L.V. Formação Águas Claras, Pré-cambriano da Serra dos Carajás: Redescrição e redefinição litoestratigráfica. Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi 1995, 7, 177–197.

- Dall’Agnol, R.; Teixeira, N.P.; Rämö, O.T.; Moura, C.A.; Macambira, M.J.; de Oliveira, D.C. Petrogenesis of the Paleoproterozoic rapakivi A-type granites of the Archean Carajás metallogenic province, Brazil. Lithos 2005, 80, 101–129.

- Golder. Anexo IV—Geologia. Estudo de Impacto Ambiental, EIA Projeto Ferro Carajás S11D. 2010. Available online: http://licenciamento.ibama.gov.br/Mineracao/Projeto%20Ferro%20Carajas%20S11D/EIA_RIMA/ (accessed on 13 April 2014).

- Sahoo, P.K.; Guimarães, J.T.F.; Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; Powell, M.A.; da Silva, M.S.; Moraes, A.M.; Alves, R.; Leite, A.S.; Júnior, W.N.; Rodrigues, T.M.; et al. Statistical analysis of lake sediment geochemical data for understanding surface geological factors and processes: An example from Amazonian upland lakes, Brazil. Catena 2018, 175, 47–62.

- Skirycz, A.; Castilho, A.; Chaparro, C.; Carvalho, N.; Tzotzos, G.; Siqueira, J.O. Canga biodiversity, a matter of mining. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 653.

- Schaefer, C.G.R.E.; Lima Neto, E.; Corrêa, G.R.; Simas, F.N.B.; Campos, J.F.; De Mendonça, B.A.F. Geoenviroments, soils and carbon stocks at Serra Sul of Carajás, Para State, Brazil. Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi Cienc. Nat. 2016, 11, 85–101.

- Mitre, S.K.; Mardegan, S.F.; Caldeira, C.F.; Ramos, S.J.; Neto, A.E.F.; Siqueira, J.O.; Gastauer, M. Nutrient and water dynamics of Amazonian canga vegetation differ among physiognomies and from those of other neotropical ecosystems. Plant Ecol. 2018, 219, 1341–1353.

- Caldeira, C.F.; Abranches, C.B.; Gastauer, M.; Ramos, S.J.; Guimarães, J.T.F.; Pereira, J.B.S.; Siqueira, J.O. Sporeling regeneration and ex situ growth of Isoëtes cangae (Isoetaceae): Initial steps towards the conservation of a rare Amazonian quillwort. Aquat. Bot. 2018, 152, 51–58.

- Guimarães, J.T.F.; Rodrigues, T.M.R.; Reis, L.S.; de Figueiredo, M.M.J.C.; da Silva, D.F.; Alves, R.; Giannini, T.C.; Carreira, L.M.M.; Dias, A.C.R.; Silva, E.F.; et al. Modern pollen rain as a background for palaeoenvironmental studies in the Serra dos Carajás, southeastern Amazonia. Holocene 2017, 27, 1055–1066.

- Viana, P.L.; Mota, N.F.O.; Gil, A.S.B.; Salino, A.; Zappi, D.C.; Harley, R.M.; Ilkiu-Borges, A.L.; Secco, R.; Almeida, T.E.; Watanabe, M.T.C.; et al. Flora of the cangas of the Serra dos Carajás, Pará, Brazil: History, study area and methodology. Rodriguesia 2016, 67, 1107–1124.

- Silva, M.S.; Guimarães, J.T.F.; Souza Filho, P.W.M.; Nascimento Júnior, W.R.; Sahoo, P.K.; Costa, F.R.; Silva Júnior, R.O.; Rodrigues, T.M.; Costa, M.F. Morphology and morphometry of upland lakes over lateritic crust, Serra dos Carajás, southeastern Amazon region. An. Acad. Bras. Ciências 2018, 90, 1309–1325.

- Moraes, A.M.; Sahoo, P.K.; Guimarães, J.T.F.; Leite, A.S.; Salomão, G.N.; Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; Júniora, W.N.; Dall’Agnol, R. Multivariate statistics and geochemical approaches for understanding source-sink relationship—A case study from close-basin lakes in Southeast Amazon. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2020, 99, 102497.

- Wetzel, R.G. (Ed.) Oxygen. In Limnology; Academic Press: London, UK, 2001; pp. 151–168.

More