The involvement of the changed expression/function of neurotrophic factors in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), has been suggested. AD is one of the age-related dementias, and is characterized by cognitive impairment with decreased memory function. Developing evidence demonstrates that decreased cell survival, synaptic dysfunction, and reduced neurogenesis are involved in the pathogenesis of AD. On the other hand, it is well known that neurotrophic factors, especially brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and its high-affinity receptor TrkB, have multiple roles in the central nervous system (CNS), including neuronal maintenance, synaptic plasticity, and neurogenesis, which are closely linked to learning and memory function.

- BDNF

- TrkB

- p75NTR

- Alzheimer’s disease

1. Introduction

2. Neurotrophins, Receptors, and Intracellular Signaling

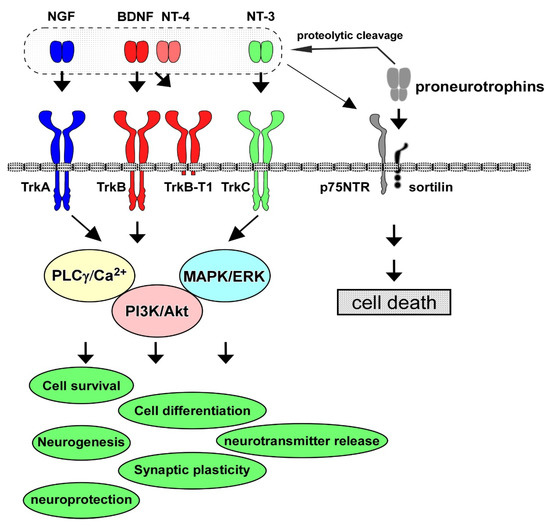

Neurotrophins have multiple roles in the PNS and CNS. The neurotrophin family consists of NGF, BDNF, NT-4/5, and NT-3, and their contribution to cell maintenance and survival in the neuronal population has been extensively investigated. The specific high-affinity receptors for each neurotrophin, Trk receptors, are a family of tyrosine kinase receptors. TrkA is the high-affinity receptor for NGF; similarly, TrkB binds to both BDNF and NT-4, and TrkC is for NT-3, and the low-affinity common receptor for neurotrophins, p75NTR, also has functional roles in the PNS and CNS [1] (Figure 1). Among these neurotrophins and their receptors, the contribution of the BDNF/TrkB system to cell survival and synaptic function has been especially investigated [6][8]. The BDNF/TrkB system exerts a positive influence on neurons, including the potentiation of synaptic plasticity (the basis for learning and memory) and cell protection against intrinsic and extrinsic stress. The activation (phosphorylation) of TrkB, which is stimulated after binding with BDNF (or NT-4), triggers three signaling pathways, including the MAPK/ERK, PI3K/Akt, and PLCγ cascades. During development, in the establishment of accurate and adequate network connections of neurons with targets, limiting the quantity of neurotrophins derived from target tissues is critical since the regulation of the number of surviving neurons depends on each neurotrophin [7][9]. Generally, the promotion of cell survival is dependent on the PI3K/Akt pathway [6][8]. Growing evidence demonstrates that the MAPK/ERK signal pathway stimulates the activation of anti-apoptotic proteins to promote neuronal survival, and the PI3K/Akt pathway suppresses pro-apoptotic proteins [8][10].

3. Roles of BDNF/TrkB System in CNS Neurons

4. BDNF/TrkB System and AD Models

Sen et al. (2015) reported the increased nuclear translocation of histone deacetylases, HDACs, by apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4), one of the genetic risk factors for AD [33][52]. It was shown that the nuclear translocation of HDACs caused the downregulation of BDNF in human neurons, although ApoE3 induced upregulation of BDNF through the acetylation of histone 3. They also found that Aβ oligomers mimicked the action of ApoE4. Interestingly, ApoE3 indued protein kinase C ε (PKCε), and PKCε activation reversed the nuclear import of HDACs by ApoE4 and the Aβ oligomer, resulting in the inhibition of BDNF downregulation [33][52]. Using human neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cells, it was demonstrated that significant downregulation of basal BDNF after Aβ treatment occurred through CREB transcriptional downregulation [34][53]. It is well recognized that the phosphorylated CREB protein is critical for the regulation of BDNF expression and its essential contribution in the CREB-mediated transcription system to the memory function process [35][54]. As evidence suggested that Aβ reduced BDNF expression mostly by decreasing the levels of pCREB protein, targeting of the CREB/BDNF pathway against Aβ toxicity was considered a beneficial approach to improving AD behaviors [35][54]. In vivo analysis revealed the downregulation of BDNF by Aβ. Xia et al. (2017) found that BDNF protein expression in both the cerebral cortex and the hippocampus of amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 (APP/PS1) Tg mice was markedly downregulated at the ages of 3 and 9 months [36][55]. Higher expression of pTau (phosphorylated Tau) is considered to be a critical hallmark of AD. A recent study using postmortem brain tissues and fluid samples revealed lower levels of proBDNF in the frontal and entorhinal cortices in AD samples compared with healthy controls [37][59]. Furthermore, AD postmortem brains exhibited decreased density of hippocampal TrkB expression compared with the controls. Interestingly, higher serum proBDNF levels correlated with lower hippocampal proBDNF or higher pTau levels [37][59], suggesting a close relationship between BDNF (and/or TrkB) and pTau in the pathology of AD.5. BDNF/TrkB System and Neuroprotection Drug Candidates for AD

Upregulation of the BDNF/TrkB system plays an important role in determining the protective effects of traditional medicine in neurodegenerative disease models. Using an experimental AD model, the effectiveness of Yuk-Gunja-Tang (YG), a Korean traditional medicine, was reported [38][61]. In scopolamine-induced memory impairment in C57BL/6 mice, the administration of YG improved impaired memory function in the Y-maze, passive avoidance, and novel object recognition tests. Interestingly, the administration of YG decreased cell death, and increased the expression of BDNF, in addition to levels of pERK and CREB [38][61]. As mentioned above, the hyperphosphorylation of Tau and its aggregation are typical neuropathological hallmarks of AD. Lin et al. (2022) examined the protective effects of analogous compounds of LM-031 (a coumarin derivative) on SH-SY5Y cells expressing ΔK280 tauRD-DsRed folding reporter [39][62]. ΔK280 tauRD is a deletion mutation of Tau found in patients with tauopathies [40][41][63,64]. Using theΔK280 tauRD-DsRed SH-SY5Y, the authors found that the LM-031 analogs LMDS-1 to -4 reduced Tau aggregation. They also found that LMDS-1 and LMDS-2 decreased the activity of caspase-1, caspase-6, and caspase-3, and the effect was reversed after the knockdown of TrkB, suggesting involvement of the BDNF/TrkB system in neuroprotection by LM-031 analogs [39][62]. Using SH-SY5Y cells expressing Aβ-GFP, the protective effects of the LM-031 analogs LMDS-1 to -4 have also been demonstrated. Since both amyloid plaques, through the accumulation of Aβ, and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), through the accumulation of soluble Tau, are neuropathological hallmarks of AD, the possibility of a relationship between Tau toxicity and Aβ aggregation in the regulation of BDNF expression is very interesting. It was demonstrated, using in vivo system, that the overexpression of Tau caused downregulation of BDNF. To improve behavior in neurodegenerative disorders, including AD, natural products that upregulate the BDNF/TrkB system have been the focused of research [42][69] (see Figure 2). In particular, the beneficial action of flavonoids for achieving neuroprotection in the pathogenesis of AD has been intensively investigated [43][70]. Importantly, 7,8-dihydroxyflavone (7,8-DHF) acted as a TrkB agonist by binding to the extracellular domain of TrkB, and exerted BDNF-like activity [44][71]. Synthetic prodrug R13 has been produced to improve the poor oral bioavailability of parent compound 7,8-DHF [45][72]. The R13 showed significant upregulation of 7,8-DHF’s pharmacokinetic profile. It was also confirmed that the chronic oral administration of R13 induced TrkB activation and inhibited Aβ deposition, hippocampal synapse loss, and decreased memory function in 5XFAD mice [45][72]. Furthermore, using the 5XFAD mice, Li et al. (2022) reported hippocampal activations of TrkB, ERK, and Akt signaling after intragastrical treatment with R13 [46][73]. Because mitochondrial dysfunction is related to AD [47][74], they performed mitochondriomics analysis, and found that R13 increased the levels of ATP and the expression of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation-related proteins, such as complex I, II, III, and IV, in the hippocampus of AD model mice. The downregulation of Aβ plaque and pTau following R13 treatment was also confirmed in their systems. Interestingly, it has been reported that chrysin (5,7-dihydroxyflavone) potentially binds to TrkA, TrkB, and p75NTR [48][75]. Hypothyroidism (which causes AD-like cognitive function) model mice, induced through continuous exposure (31 days) to methimazole in drinking water, exhibited memory deficits (Morris water maze test) and downregulation of BDNF and NGF. However, improved spatial memory function and increased BDNF expression in the hippocampus, and increased NGF in both the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, were observed after the intragastrical administration of chrysin for 28 consecutive days [48][75]. Using an AD mouse model induced through an injection (i.c.v) of Aβ1–42, the effect of Kaempferide (KF), one of the flavonoids derived from Alpinae oxyphylla Miq, was examined. After Aβ1–42 exposure, KF administration (i.c.v) for five consecutive days was performed. As expected, behavioral tests (Y-maze test and Morris water maze test) revealed that KF prevented cognitive decline in the mice that received Aβ1–42 injection. The administration of KF upregulated the activities of BDNF/TrkB and CREB signaling in the hippocampus [49][76].6. Other Neurotrophic Factors in AD

6.1. Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF)

GDNF, one of the most widely known neurotrophic factors, was discovered as the first member of the GDNF family of ligands in the CNS in a rat glial cell line [50][78]. Generally, it is well known that glial cells, including astrocytes, produce GDNF [51][79]. GDNF is also produced by dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and has protective effects on dopaminergic and other types of neurons. GDNF and its receptors are widely distributed throughout the brain and are present in the spinal cord, kidneys, and other organs [52][80]. Regarding the role of GDNF in the CNS, studies using heterozygous knockout animals have shown that GDNF is involved in neurogenesis and the regulation of brain functions, such as the modification of mental conditions and suppression of drug dependence [53][54][55][81,82,83]. GDNF family receptor alpha (GFRα) is bound to the cell membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor and acts as the main receptor for GDNF [56][84]. Four types of GFRα, including GFRα1, α2, α3, and α4, are known. When GFRα1 binds to the GDNF homodimer, the receptor interacts with rearranged during transfection (RET), and activates it. Activated RET triggers multiple signaling pathways, including the PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways [57][85]. While RET alone has pro-apoptotic activity [58][86], the activation of these downstream signaling pathways is thought to be responsible for GDNF-induced neuronal survival, as both the PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways prevent neuronal cell death [59][87]. Marksteiner et al. (2011) reported that GDNF was reduced in the plasma and increased in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with early-stage AD [60][91]. Straten et al. (2011) showed similar results of reduced serum GDNF and increased in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with AD [61][92]. Another study also reported the downregulated expression of BDNF, NGF, and GDNF in patients with mild cognitive impairment and moderate AD [62][93].6.2. Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF, or FGF-2)

bFGF, also known as FGF-2, is a heparin-binding protein with a molecular weight of 18–34 kDa. This growth factor was identified in 1974 in the bovine pituitary gland as a molecule that promoted fibroblast proliferation [63][101]. bFGF, initially named for its role in fibroblast proliferation, is a multifunctional growth factor involved in a variety of cellular processes. During development, bFGF contributes to mesoderm induction, anterior–posterior axis patterning, limb formation, and neurogenesis [64][102]. In adulthood, bFGF contributes to angiogenesis and wound healing by acting on various cell types [65][103]. bFGF is primarily produced as a polypeptide of 155 amino acids, resulting in an 18 kDa protein. Isoforms of 22 kDa (196 amino acids), 22.5 kDa (201 amino acids), 24 kDa (210 amino acids), and 34 kDa (288 amino acids) are also synthesized due to alternative start codons with N-terminal extensions of 41, 46, 55, or 133 amino acids, respectively [66][67][104,105]. Typically, the low-molecular-weight (LMW) form of 18 kDa (155 amino acids) is located in the cytoplasm and secreted from cells, whereas the high-molecular-weight (HMW) form is delivered to the cell nucleus [68][106]. bFGF binds to FGF receptors (FGFRs) on the cell membrane. The binding induces the formation of FGFR dimers, and the dimerization triggers the activation (phosphorylation) of tyrosine kinase domains, which act as docking sites for other signaling proteins. Heparan sulfate is involved in the dimerization process [69][107]. The signaling pathways stimulated through the activation of FGFR are the Ras, PLC-γ, Janus kinase (JAK) signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat), and PI3K/Akt pathways, which regulate a variety of gene expression and cellular processes [70][108]. In the CNS, bFGF is expressed in various cell populations, such as neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia [71][72][109,110]. bFGF can cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) when applied systemically. Using APP23 transgenic mice as a model of amyloid pathology in AD, Katsouri et al. (2015) found that exogenous bFGF administration improved Tau pathology and spatial memory impairment by downregulating BACE1 [73][121].6.3. Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1)

IGF-1 is a pleiotropic hormone whose structure is similar to that of insulin. IGF-1 is produced in various tissues, including the brain, is recognized to be an essential factor for cell growth and differentiation, and contributes to the maintenance of various organs [74][75][127,128]. IGF-1 binds to the IGF-1 receptor (IGF1R) and/or insulin receptor (IR). The activation of receptor tyrosine kinases results in the phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrates (IRSs), which are linked to IGF1R and IR. Adaptor proteins bind to the phosphorylated IRSs, thereby transmitting signals to downstream pathways, including PI3K/Akt [76][129]. IRSs have pleckstrin homology and phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domains at the N-terminus, and PI3K-, Grb2-, and SH2-binding domains at the C-terminus. Mammals have four types of IRS (IRS1-4) [77][130]. IRS1 and IRS2 are ubiquitously expressed in almost all organs of the body. IRS3 is observed only in adipocytes (human IRS3 is a pseudogene). IRS4 is mainly expressed in the hypothalamus, showing different expression patterns from those of IRS1 and IRS2 [78][79][131,132]. Although these IRSs display differences in their structure and expression patterns, common downstream signaling pathways are activated. Unlike the peripheral IGF-1-target tissues, there are significant differences in the distribution and expression between IR and IGF1R in the brain, although their expression in some brain regions is still unclear [77][130]. Brain-specific IR-deficient (bIR−/−) and neuron-specific IGF1R-deficient (nIGF1R−/−) mice have been generated [80][133]. To examine the possible involvement of IR and/or IGF1R in the pathogenesis of AD, the AD model mice (Tg2576) were crossed with their respective knockout mice. Tg2576 mice crossed with nIGF1R−/− (Tg2576 X nIGF1R−/−) showed prolonged survival and improved AD pathology and cognitive dysfunction, similar to those crossed with IGF1R heterozygous (IGF1R+/−) mice (Tg2576 X IGF1R+/−) [81][82][83][84][134,135,136,137]. Another study demonstrated that heterozygous brain-specific IGF1R-deficient (bIGF1R+/−) mice showed improved mortality without affecting the pathology of Tg2576 mice (Tg2576 X bIGF1R+/−) [85][138]. Among the four IRSs (IRS1-4), IRS2 has been most thoroughly investigated. For example, it was reported that IRS2 KO mice exhibited a striking phenotype of juvenile lethality associated with insulin resistance and the development of severe diabetes [86][141]. Although IRS2 is expressed throughout the body, it is also widely distributed in the brain and highly expressed in neurons. Using double mutant mice generated by crossing IRS2−/− mice with Tg2576 mice, it was revealed that IRS2 deletion improved all pathological features (decreased cognitive function and mortality in Tg2576 mice) [87][142]. Tg2576 mice crossed with nIGF1R−/− (Tg2576 X nIGF1R−/−) showed similar improvement [81][134]. These AD mouse model studies suggest that IGF-1 signaling exacerbates AD.7. Conclusions

Neurotrophic factors contribute to the growth, survival, and function of brain neurons, and have attracted attention for their application in the treatment of AD. In particular, BDNF, one of the most well-known neurotrophic factors, exhibits diverse physiological activities in the CNS, such as the maintenance of neuronal survival, the morphogenesis of neurites, and the regulation of synaptic plasticity, through its tyrosine kinase-type receptor, TrkB. When administered to the brains of AD animal models, BDNF inhibits the loss of nerve cells and restores neural functions, and thus, is expected to be used as a therapeutic agent for the disease. Moreover, accumulating evidence suggests that other neurotrophic factors, including NGF, GDNF, and bFGF, also have neuroprotective potential and are promising targets for AD.