Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Pasquale Pagliaro and Version 2 by Catherine Yang.

Nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO) represent a pair of biologically active gases with an increasingly well-defined range of effects on circulating platelets. These gases interact with platelets and cells in the vessels and heart and exert fundamentally similar biological effects, albeit through different mechanisms and with some peculiarity. Within the cardiovascular system, for example, the gases are predominantly vasodilators and exert antiaggregatory effects, and are protective against damage in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Differently from NO, only a limited number of studies have been carried out on CO effects on platelets and CO and cardioprotection.

- platelets

- preconditioning

- remote conditioning

- nitrosating agents

1. CO and Cardioprotection

The cardioprotective action of CO is mediated by the opening of KATP and consequent inhibition of the opening of the MPTP. It has been observed that CO donors (CORM) [1][109] demonstrate a protective effect, reporting a certain influence of sex on cardioprotection. In fact, as known from the literature, sex determines the expression of specific genes and proteins involved in protection of mitochondrial and myocardial function, such as Akt [1][109].

The protective action exerted by CO at low doses allows the maintenance of mitochondrial function, in fact, it has been observed that in these conditions it is able to maintain the mitochondrial membrane potential stable, which is altered in ischemia/reperfusion injury [2][97].

It has also been reported that CO is able to modulate the synthesis of mitochondrial ROS, the activity of some hemoproteins, including cytochrome c, and inflammation (inflammasome-dependent) [3][4][110,111]. Although mitochondrial ROS are involved in cardioprotection [5][6][7][8][8,9,10,112] and mitochondrial ROS induced by NO are cardioprotective [9][113], it is not known if ROS generated by exogenous CO are cardioprotective.

2. CO and Platelets

Although early studies showed stimulating CO effects on platelet aggregation, more recent studies have indicated a CO ability to inhibit platelet aggregation and release of ADP and serotonin from their granules [10][11][114,115] (Table 1).

CO and NO share some chemical and biological properties [12][116]. Indeed, exogenously added CO inhibits platelet aggregation mainly by elevating intracellular levels of cGMP [12][116]. Gaseous CO shows antiaggregating properties with similarity with NO in increasing sGC activity as result of direct binding of CO to the iron present in the heme moiety of sGC, even if CO is 30–100 times less potent than NO [11][13][115,117]. There is agreement on the concept that the inhibitory actions of CO on platelets are relatively low in comparison to those exerted by the endothelium-released agents NO and prostacyclin [14][118]. Actually, only high concentrations of gaseous CO (100%) seem to reduce platelet aggregation via sGC activation [13][117].

Platelets are the target but also the source of CO given that platelets express heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) and are involved in multiple steps of heme and bilirubin metabolism [15][119]. In the presence of HO-1 activators, such as hemin- and sodium arsenite, platelet agonist-induced aggregations are reduced and margination and rolling are prevented, these effects are abolished by the HO-1 inhibitor zinc protoporphyrin IX (ZnPP-IX) and reproduced by CO [16][17][120,121]. Even if under basal condition, HO-1 does not significantly influence platelet-dependent clot formation in vivo, in the presence of increased HO-1 production, platelet-dependent thrombus formation is suppressed [18][122]. These findings induced the authors to suggest that the enhanced HO-1 expression may be a mechanism able to reduce platelet activation under prothrombotic states. A study using HO-1 knockout mice found normal platelet number, bleeding time, and platelet aggregating characteristics, but accelerated thrombosis, at least partially, due to platelet activation, which was rescued by inhaled CO [19][123] or CO-donor [20][124].

The unexpected physiological roles of CO in the cardiovascular system have justified the development of CO-releasing compounds [21][125] and the evaluation of their effects also on platelet function. Actually, CO-donor compounds have been shown to effectively inhibit human platelets without involving the activation of sGC [10][114] even if NO- and CO-mediated effects on platelets seem to be interlinked given that the inhibition of sGC increases the inhibitory CO effects.

CO is able to reduce the calcium signal elicited by platelet agonists by a direct effect on calcium entry [22][126], thus, confirming a role for HO activity in modulating platelet response. Different mechanisms could explain CO effect on intraplatelet calcium levels. On the one hand, CO can induce a cGMP-mediated decrease in calcium release from intracellular stores or an acceleration in the rate of its back-sequestration. On the other hand, CO shows the ability to directly inhibit the pathway involved in calcium entry [22][126]. The direct role of CO on capacitative calcium entry may be responsible for its antiaggregatory action.

Other cGMP-independent mechanisms by which CO-donors can inhibit platelet function include the CO ability to interfere with glycoprotein-mediated HS1 phosphorylation, a signaling molecule involved downstream of glycoprotein activation. In particular, it has been shown that during lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced platelet activation, the signal transmitted between membrane glycoproteins and HS1 is suppressed by CO-releasing molecules [23][24][127,128].

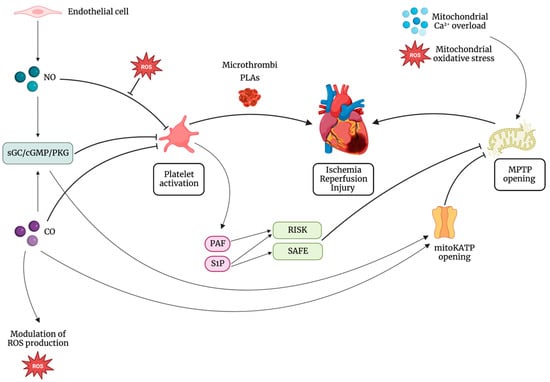

The effect of CO on platelets may be also due to its effect on the cytochrome P450 enzymes with subsequent prevention of generation of arachidonic acid, a powerful proaggregating agent [25][26][129,130]. Figure 12 summarizes platelet–gases interactions in the cardioprotective scenario.

Figure 12. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) opening is the main end effector in ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI). On one side, platelets contribute to IRI mainly by microthrombi formation and platelet-leukocyte aggregates (PLAs). On the other side, molecules of platelet origin, such as platelet activating factor phosphoglyceride (PAF) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), lead to the activation of cardioprotective pathways, such as the reperfusion injury salvage kinase (RISK) pathway and the survivor activating factor enhancement (SAFE) pathway, all targeting inhibition of MPTP opening. Besides, the interaction between platelets and gasotransmitters has a central role in cardioprotection. Nitric oxide (NO) activates the soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC)/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)/cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) pathway, leading to the inhibition of platelet adhesion, activation, and aggregation. NO can inhibit platelet response also by cGMP-independent mechanisms. NO inhibitory effect on platelets is reduced in the presence of increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Also, PKG leads to the opening of the mitochondrial ATP-dependent K+ channel (mitoKATP) and subsequent inhibition of MPTP. Carbon monoxide (CO) exerts its cardioprotective action triggering the opening of mitoKATP with consequent inhibition of the opening of MPTP and modulating mitochondrial ROS production. Furthermore, it can inhibit platelet activation both by cGMP-dependent and cGMP-independent mechanisms.

Table 1. The main stimuli and pathways involved in nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO)-induced effects on platelets. Abbreviations: eNOS endothelial nitric oxide synthase; iNOS inducible nitric oxide synthase; HO-1 heme oxygenase 1; cGMP cyclic guanosine monophosphate; HNO Nitroxyl; PKG protein kinase cGMP-dependent; IL-1β interleukin-1 β; PKC protein kinase C; ONOO− peroxynitrite.

| Gas | Stimuli | Production | Main Pathway | Effect(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO | Shear stress, VEGF, insulin | Endothelial cells (eNOS) |

NO/cGMP/PKG | Vasodilation |

| [Ca]i increase, interaction protein (HSP70, HSP90, caveolin), insulin, β2 stimulation, acetylsalicylic acid, adenosine, and forskolin |

Platelets (eNOS) |

NO/cGMP/PKG | Reduction of adhesion, activation, and aggregation |

|

| Inflammation | Platelets iNOS |

NO/cGMP/PKG | Increased production of NO correlates with IL-1β |

|

| Conditioning ischemia | Cardiac cells (eNOS or iNOS) |

NO/cGMP/PKG S-nitrosylation |

Cardioprotection | |

| HNO | Conditioning ischemia | Cardiac cells (eNOS?) | PKCε translocation to the mitochondria |

Cardioprotection |

| ONOO− | Metabolic diseases | NO + O2− | nitration carbonylation and peroxidation |

Alteration of haemostatic functions |

| CO | Hemin and sodium arsenite | Platelet HO-1 |

cGMP/PKG | Reduction of aggregation and release of ADP and 5-HT |

| Conditioning ischemia | Cardiac cells HO-1 |

Opening of KATP channel and closure of the MPTP. |

Cardioprotection |