Human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs), once external pathogens, now occupy more than 8% of the human genome and represent the merge of genomic and external factors leading to the development of cancers. Certain HERVs have perfectly assimilated into the cellular environment preventing oncogenesis, while others maintain their pathogenic potential and remain undercover until a time of cellular dysregulation. In particular, HERV genes such as gag, env, pol, np9, and rec have been discovered to carry central roles in immune regulation, checkpoint blockade, cell differentiation, cell fusion, proliferation, metastasis, and cell transformation in tumor environments. In addition, HERV long terminal repeat (LTR) regions have been shown to be involved in transcriptional regulation, creation of fusion proteins, expression of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and promotion of genome instability through recombination influencing oncogenesis.

- human endogenous retrovirus

- breast cancer

- leukemia

- lymphoma

- skin cancer

- reproductive cancer

- liver cancer

- prostate cancer

- gastrointestinal cancer

- renal cancer

- ERV

- retroelements

- LTR

1. Introduction

2. HERVs in Breast Cancer—The Rise of New Biomarkers

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide [62][28]. Due to the many breast cancer subtypes and their varying treatment responses [63][29], targeted treatments that evolved in recent years have become a success story. However, the field is still in need of preventive and early detection methods. HERVs might be able to close this gap providing new targets for prognostics, diagnostics, and treatments. Several groups have independently reported the overexpression of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and proteins from multiple HERV families in breast cancer cell lines and patient tissues compared to healthy tissues [64][30]. Interestingly, the menstruation-associated hormones estradiol and progesterone were observed to increase HERV-K (HML-4) env [65][31] and HERV-K (HML-4) RT transcripts as well as HERV-K (HML-4) RT protein levels [66][32] in breast cancer cell lines (Figure 1). In breast cancer patients, increased HERV-K (HML-4) RT as well as HERV-K (HML-4) Env protein levels were shown to be associated with shorter metastasis-free and overall survival [66,67][32][33]. Conversely, Montesion et al. (2018) [68][34] identified two HERV-K (HML-2) LTRs (HGCN: ERVK-5 at position 3q12.3 and ERVK3-4 at 11p15.4) that had specifically increased promoter activity in breast cancer while decreased activity in immortalized human mammary epithelial cells. Additionally, several stage-specific transcription factor (TF)-binding sites within the two LTRs were predicted to potentially contribute to promoter activity during neoplasia [68][34]. While the ERVK-5 (HERV-KII) was fixed in humans, the ERVK3-4 (HERV-K7) was found to be polymorphic in the human population with an allele frequency of 51%, presenting the prospect of a newly identified risk facto r [68][34]. In addition, breast cancer cell lines were shown to harbor HERV-K111 gene conversion/deletion events in the pericentromeric region of chromosome 22, suggesting a contribution to genomic instability [69][35].

3. HERVs in Lymphoma—The Silent Inducers

4. HERVs in Leukemia—The Lifesavers for Cancer Cells

Leukemias are the most common childhood cancers worldwide [62,121][28][60] and among the cancers with the lowest somatic mutational burden [122][61]. Both characteristics suggest genomic risk factors that can be inherited, and when accumulated, lead to carcinogenesis. Analogous to observations made for HERV LTRs in prostate cancer (see HERVs in Prostate Cancer—The Dancing Partner of the Androgen Receptor), THE-7 LTRs were discovered as drivers of a translocation of chromosome 14q32 to chromosome 7q21 in a female patient with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) [123][62]. Furthermore, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) was found to be constitutively activated through the fusion between a HERV-K3 (HML-6) sequence (HGCN: ERVK3-1) and the FGFR1 gene in a male patient with an atypical stem cell myeloproliferative disorder [124,125][63][64]. The fusion and resulting aberrant growth signal were the result of a translocation involving chromosomes 19q13.3 and chromosome 8q12 [124,125][63][64]. Furthermore, deletions of pericentromeric HERV-K111 regions in adult T-cell leukemia cell lines were enriched leading to chromosomal instabilities [69][35]. Additional to these chromosomal abnormalities as prognostic markers, Schmidt et al., (2015) identified single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers near two endogenous retroviral loci, HERV-K (HML-2) on chromosome 1 (HGCN: ERVK-7) and HERV-Fc1 on chromosome X (HGCN: ERVFC1) associated with multiple myeloma [126][65]. Both HERV regions encode nearly complete viral proteins, suggesting a functional involvement of the gene products in disease development [126][65]. Similar to the observations in lymphomas, the immune response against HERV-K (HML-2) and other HERVs appears to be rather weak or unexplored (see also HERVs in Lymphoma—The Silent Inducers) [100][66]. This might also be due to the fact that HERV-K108 (HGCN: ERVK-6) Env TM has immunosuppressive properties and has been reported to induce IL10 in PBMCs [127][67]. IL10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine, which terminates T-cell responses and leads to immune tolerance [128][68]. In a comparable way, surface CD5 expression on B cells regulates their functional fate and immunological activity. CD5 expression is tightly controlled through a HERV-E sequence located upstream of the CD5 locus (HERV-E::CD5). The HERV-E::CD5 sequence was shown to induce the integration of an alternate exon, resulting in low levels of membrane CD5 in normal B cells [129][69].5. HERVs in Skin Cancer—The Highly Addictive Treatment Targets

Compared to other organs, the skin is exposed to some of the highest amounts of mutagens; therefore, skin cancer is the malignancy with the highest mutational burden [122][61]. Accordingly, several physical and chemical agents with mutagenic potential have been proven to influence the regulation of HERV sequences [9,10][9][10]. As such, UV radiation, the primary risk factor for both melanomas and non-epithelial skin cancers, was shown to induce gag expression of HERV-K (HML-2) [143][70] in melanoma cell lines and tumor tissues; to reduce rec and np9 expression of HERV-K (HML-2) in primary human melanocytes and melanoma [144][71]; and to reduce pol expression of HERV-K, -H, -L, -FRD, -E, and ERV9 in melanoma cell lines [145][72], primary keratinocytes [146][73], and skin biopsies (Figure 43) [147][74].

6. HERVs in Testicular Cancer—The Governors of Tumor Suppressor Genes

7. HERVs in Other Genital Cancers (Ovary Cancer, Choriocarcinoma, and Endometrial Cancer)—The Ascent of New Possibilities

8. HERVs in Colorectal and Gastrointestinal Cancers—The Hopes and Hazards of Family H

Colorectal cancers (CRCs) are among the most common cancers worldwide with strikingly low 5-year survival rates of less than 65–70% in Northern America, Australia/New Zealand, and many European countries [62][28]. While early diagnosis has markedly improved for older patients due to routine screenings in individuals >50 years of age, rising rates in the population under 45 years of age highlight the need for improved non-invasive prognostic and diagnostic tools [213][107]. In the last decade, research has started to focus on the influence of HERV elements on CRCs and has revealed interesting interactions, especially involving HERV-H. With over 1000 loci in the human genome, HERV-H is the most abundant HERV family carrying coding regions in the human genome [214][108]. A link between chronic inflammation and cancer has been established for various tumors, and, specifically for CRCs, an inflammatory microenvironment has been recognized to be a cause, hallmark, and consequence of disease [221][109]. A subset of patients with colon cancer was shown to express a HERV-H_9q24.1::IL33 fusion transcript required for tumor growth [222][110]. IL33 is a proinflammatory cytokine produced by epithelial and endothelial cells [223][111] that has been demonstrated to correlate in its expression with CRC progression and metastasis [224][112]. The particular function of the HERV-H_9q24.1::IL33 product is unknown but, based on the function of native IL33, might include roles as a modified cytokine or nuclear factor regulating gene transcription [223][111]. Further, HERV LTR promoted chimeric transcripts detected specifically in CRC tissues and cell lines including the ion transporter SLCO1B3λπ, which is frequently mutated in CRC [222][110]. In contrast to fusion transcripts that result in aberrant cellular genes, TIP60 (HGNC: KAT5) has been described as a regulator of the inflammatory effects of HERV expression inside the cell [225][113]. KAT5 is a tumor suppressor that is found to be repressed in early stages of CRCs and breast cancers [225][113]. A publication by Rajagopalan et al. (2018) indicated that KAT5 downregulation results in increased levels of HERV expression and associated inflammatory responses [225][113]. In normal cells, KAT5 induces H3K9 trimethylating enzymes SUV39H1 and SETDB1 in a BRD4-dependent manner, which leads to global inhibitory methylation of HERV loci [225][113]. In KAT5-repressed cancer cells, the study investigators detected induction of IRF7 mediated by the intracellular pathogen sensing STING (HGNC: TMEM173), resulting in an inflammatory response and further tumor growth [225][113]. While viral gene products are readily detected by innate immune receptors, most cellular lncRNAs escape the surveillance mechanisms and, in this fashion, are able to interfere with regulatory pathways. For instance, the lncRNA EVADR on chromosome 6q13 was observed to be induced by the ERV1 LTR MER48 specifically in colon, rectal, lung, pancreas, and stomach adenocarcinomas [226][114]. In a similar way, the ERV1 LTR MER61C on chromosome 514.1 drives transcription of the lncRNA PURPL (LINC01021), which is increased in CRC cell lines and tumors [227,228][115][116]. While higher EVADR expression was associated with slightly decreased patient survival rates [226][114], CRC tumors with higher levels of PURPL RNA resulted in improved survival rates, and induced expression in CRC cell lines lead to increased chemosensitivity according to Kaller et al. (2017) [227][115].9. HERVs in Liver Cancer—The Opening Chapter

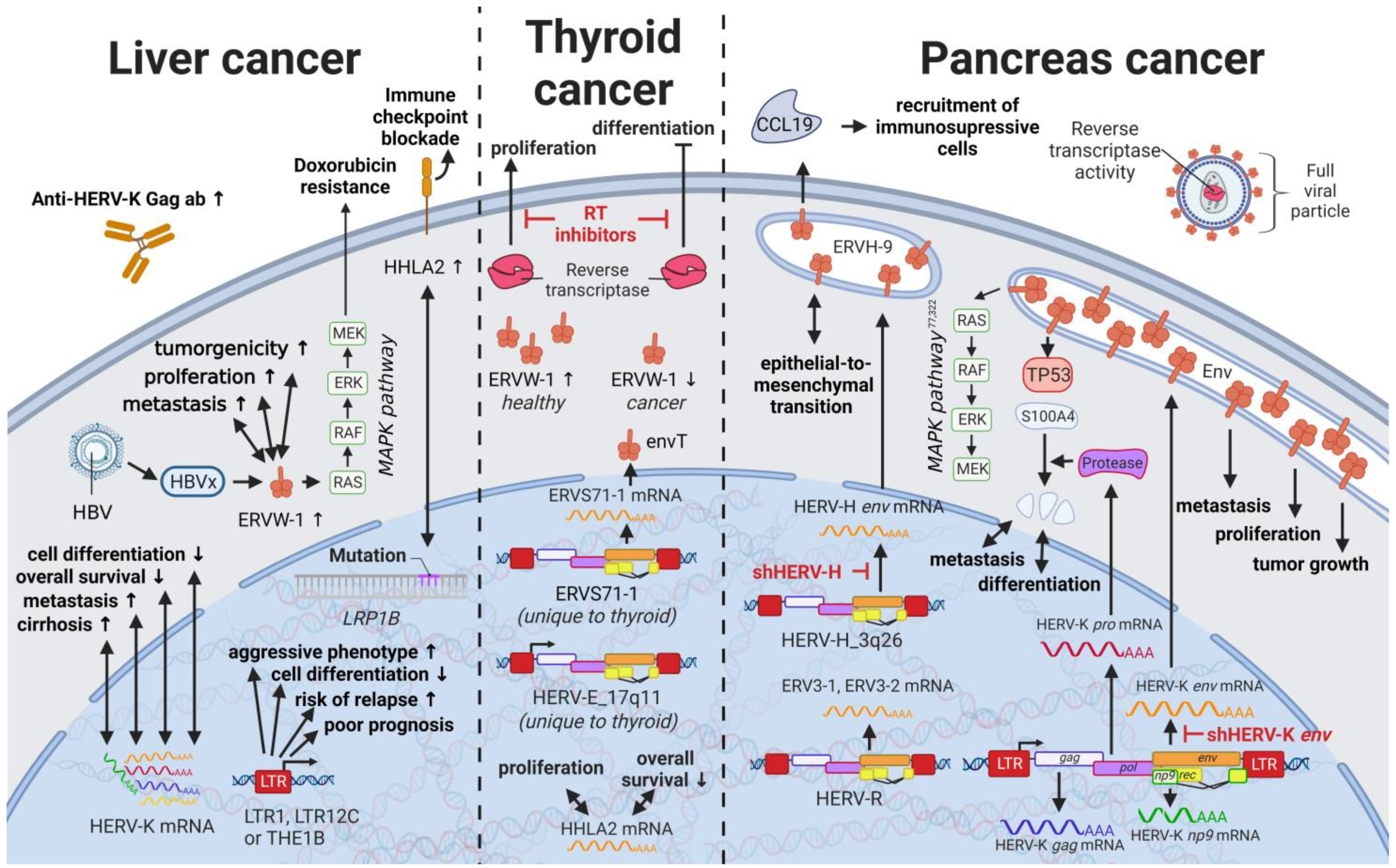

Liver cancers are the third leading cause of cancer-related death in males worldwide [235][117]; however, only limited reports are available on the influence of HERVs in liver cancer oncogenesis. Ahn and Kim (2009) together with Liang et al. (2009) reported increased expression of HERV-H, HERV-R.3-1, and HERV-P in overall liver cancers without taking into consideration distinct cancer subtypes [236[118][119],237], while several other groups reported the distinct activation of HERV-K (HML-2) and HERV-P in hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) specifically [238,239][120][121]. However, a study by Liu et al. (2021) demonstrated that the LRP1B mutation was associated with the overexpression of HERV-H LTR-Associating 2 (HHLA2) in patients with HCC [231][122]. HCC has a high morbidity and constitutes more than three-fourths of all cases with liver cancer [62][28]. Interestingly, a large number of HERV LTRs, including LTR1, LTR12C, and THE1B, were found upregulated in human HCC tumors (Figure 75) [240][123]. HCC tumors with high LTR activation were associated with high risk of relapse [240[123][124],241], a more aggressive phenotype [240[123][124],241], poor prognosis [241][124], and impaired cell differentiation in animal models [16,242][16][125]. Moreover, HERV-K (HML-2) gene products, while only moderately elevated in patients [243][126], were described to positively correlate in their expression with tumor cell dedifferentiation, mortality rates, TNM stage, and cirrhosis in HCCs [239][121]. Furthermore, in a subgroup of patients with HCC antibodies against HERV-K (HML-2) Gag were found indicating the immunogenicity of the viral gene product [238,243][120][126]. Additional to its potential as prognostic marker and therapeutic target, HERV-K (HML-2) expression might also provide resolution to a dispute concerning the origin of a liver cancer cell line. It is still debated whether HepG2 cells are derived from HCC or hepatoblastoma.

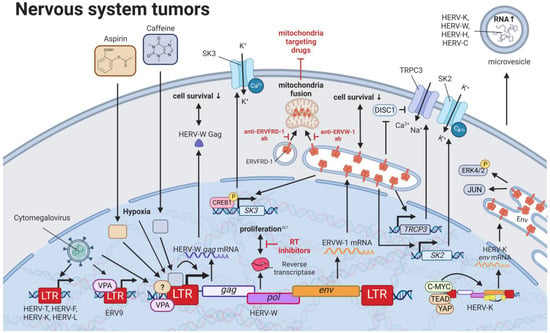

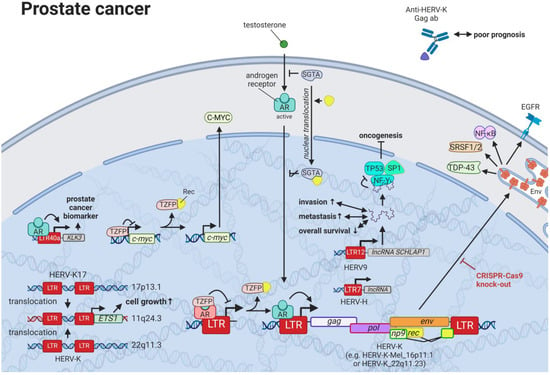

10. HERVs in Nervous System Cancers—The Wicked Side of HERV-W

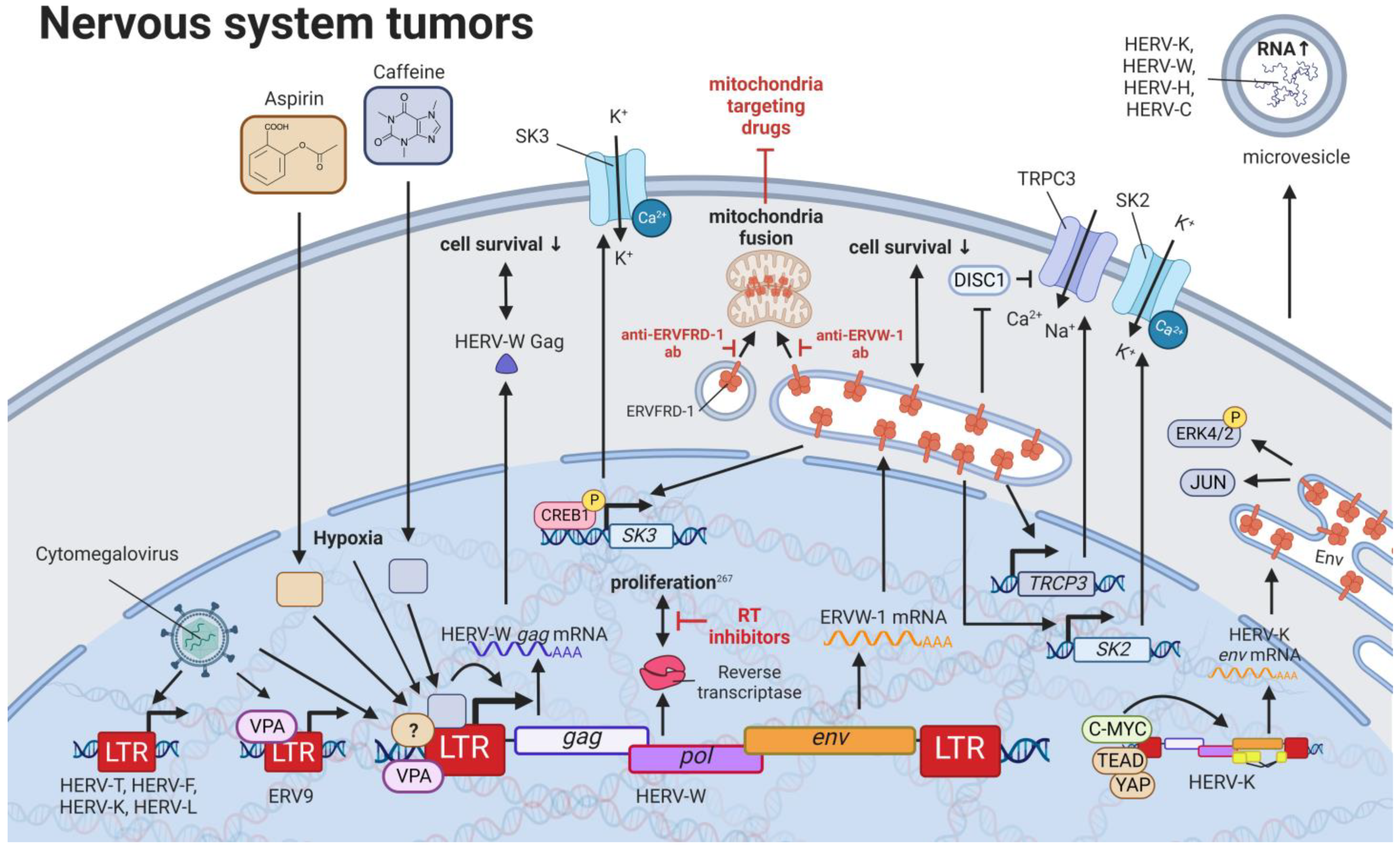

11. HERVs in Prostate Cancer—The Dancing Partner of the Androgen Receptor

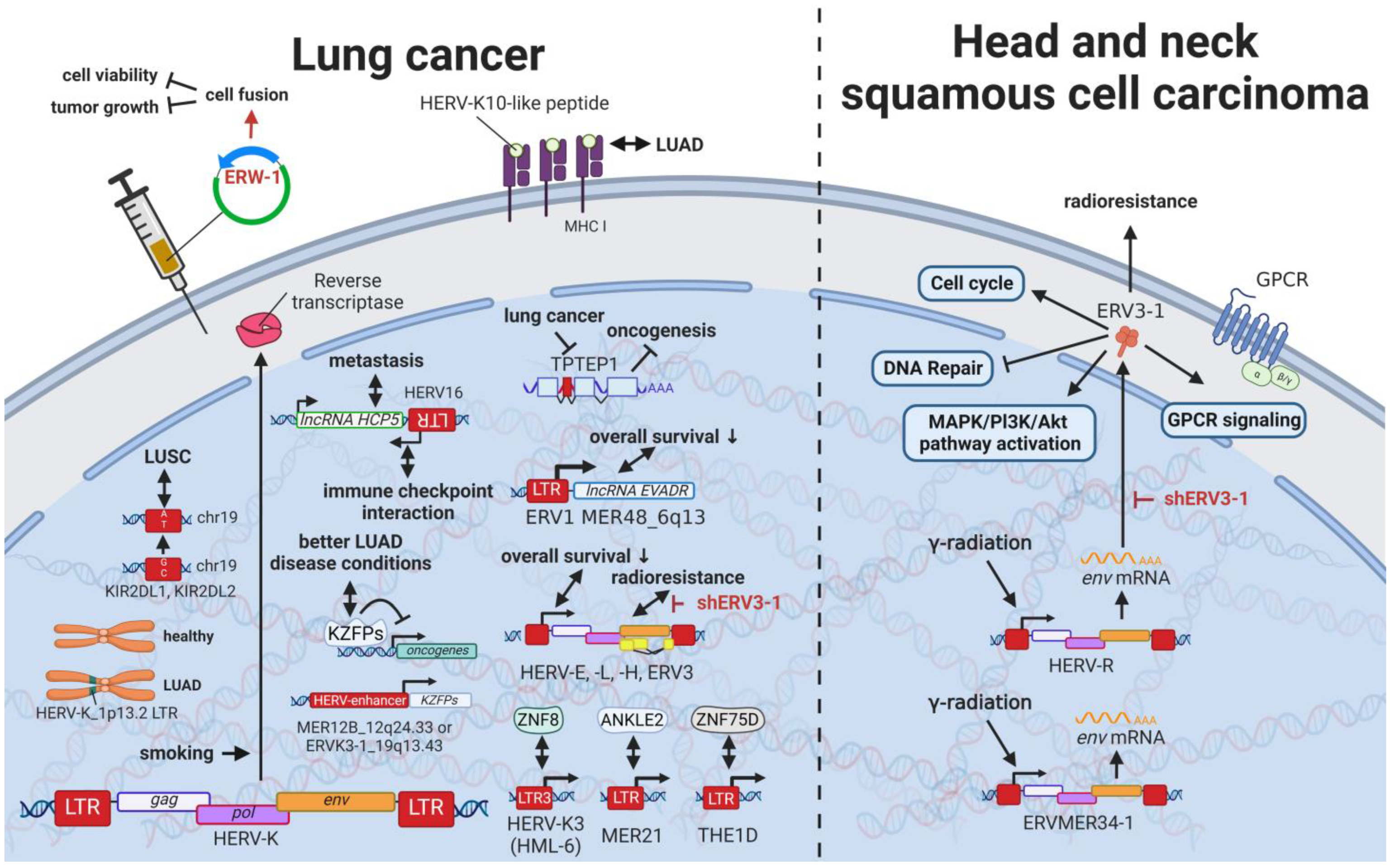

12. HERVs in Lung Cancer—The Love for Long Noncoding RNAs and Pseudogenes

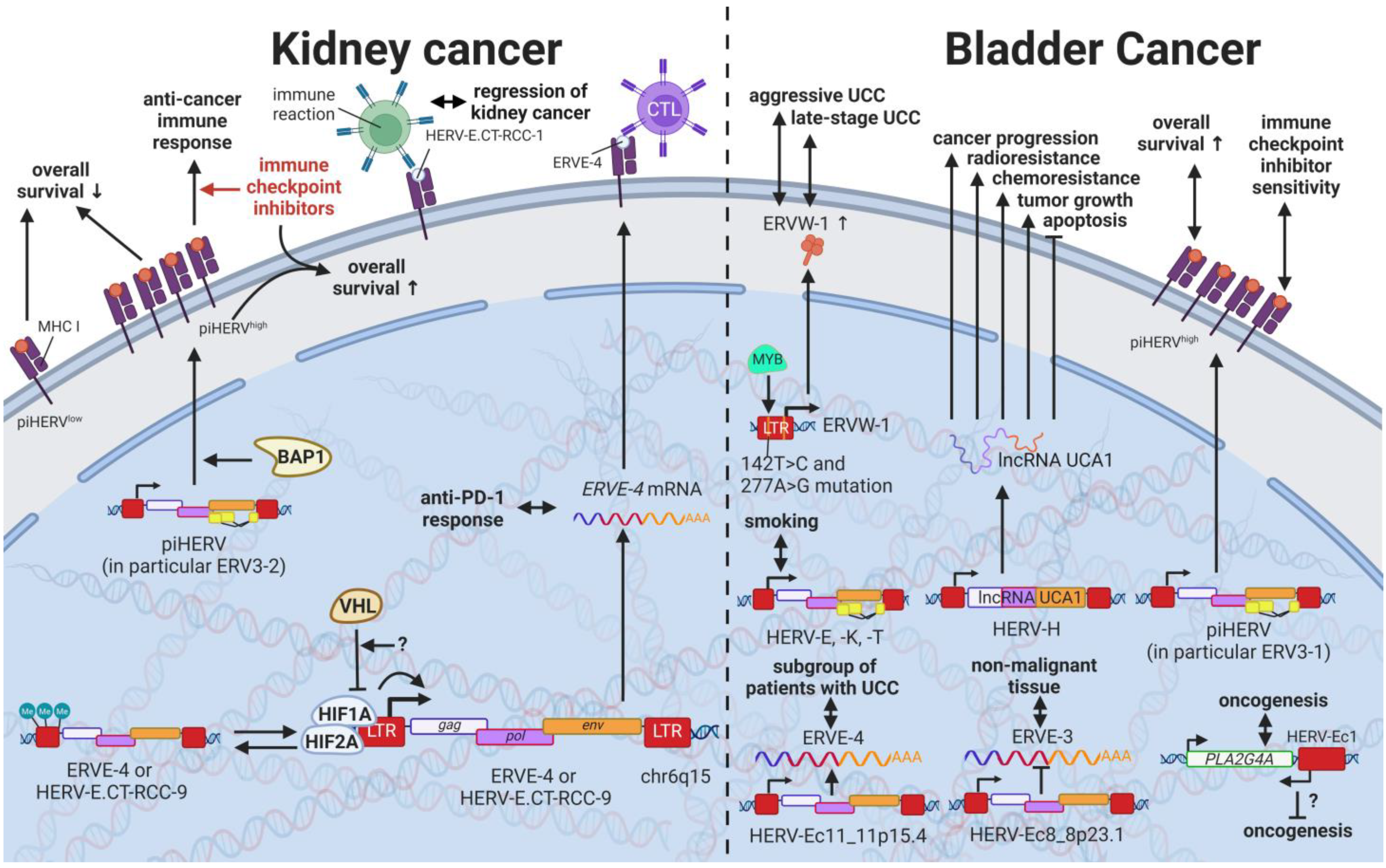

13. HERVs in Cancers of the Urinary System (Kidney and Bladder Cancer)—The Future Fire Fighters

While most HERVs operate below immune detection, research has shown that upregulation of HERVs in transformed cells can serve as a physiological tumor recognition signal, preventing the propagation of cancerous cells in early stages [117,140,203,230][146][147][148][149]. In advanced-stage cancers, such tumor suppressive functions are disrupted on multiple levels, one being through immune checkpoint activation [299][150]. Hence, newly developed immune checkpoint inhibitors have proven to be effective regimens for persistent cancers, especially for clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), where clinically significant and robust responses have been observed [300][151]. To further enhance antitumor immune responses upon immune checkpoint blockade, Panda et al. (2018) examined HERVs as prospective inducible targets in patients with ccRCC [71][37]. The study investigators determined the subset of potentially immunogenic HERVs (piHERVs) with the greatest potential to induce immune responses, such as immune infiltration, higher cytotoxic T-cell levels, and M1 macrophage abundance (Figure 119) [71][37]. Despite lower overall survival of patients with higher expression of such HERVs, piHERVhigh patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors experienced significantly improved prognosis and treatment responsiveness compared to their piHERVlow counterparts [71][37]. Out of all piHERVs, HERV-R.3-2 env (ERV3-2) expression was particularly increased in responders compared to non-responders, highlighting its tumor suppressive functions mentioned for other cancers (see HERVs in Lymphoma—The Silent Inducers and HERVs in Other Genital Cancers (Ovary Cancer, Choriocarcinoma, and Endometrial Cancer)—The Ascent of New Possibilities) [71][37]. Interestingly, similar results have been observed for patients with urothelial cancer who displayed high piHERV expression [301][152].

14. HERVs in Endocrine Cancers (Pancreas and Thyroid Cancer)—The Unknown Potential

15. HERVs in Other Cancers (Osteosarcoma, Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma)—The Hodgepodge of Hope for Novel Therapies

Rare cancers, by definition, only provide limited case numbers for investigation. Accordingly, only single reports of HERVs evaluated in such cancers are available. Despite a high incidence in children, osteosarcoma is a rare malignancy in adults [337][165]. A single study on human osteosarcoma reported the statistically significant upregulation of 35 and downregulation of 47 HERV mRNAs in osteosarcoma tissues compared to healthy controls [337][165]. The most significant HERV elements differentially expressed included LTRs of the HERV-L, HERV-K (HML-2), and ERV-1 [337][165]. Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) comprise 90% of all head and neck cancers and are relatively common [341,342][166][167]. HNSCCs are often inoperable due to the complex anatomy, making radio- and chemotherapy the only option [343][168]. Accordingly, radioresistance poses a major problem resulting in very low survival rates [62,343][28][168]. Findings by Michna et al. (2016) documenting an induction of ERV3-1 and ERVMER34-1 env upon exposure of HNSCC cell lines to γ-radiation indicate a potential target to overcome radioresistance [341][166].16. Novel Options for Cancer Treatment Facilitated by HERVs

Many studies have demonstrated increased HERV levels in tumor cell lines and tumor tissues compared to normal healthy tissues, suggesting two potential treatment approaches. On the one hand, strategies have been proposed that target pathways in which HERVs are involved [234,345,346][169][170][171], as outlined for various cancers above. HERVs might provide another pharmacological target in this way. Moreover, HERV-derived HERV restriction factors such as suppressyn (HGCN: ERVH48-1), a HERV-F-derived inhibitor of ERVW-1ε-mediated fusion, might serve as a starting point for drug development. However, discoveries of HERV genes and LTRs involved in regulatory mechanisms are very new and still advancing with the recent development of more accurate and affordable sequencing techniques.

On the other hand, treatment strategies targeting HERV proteins as tumor-specific antigens have been suggested [83[172][173],84], assuming HERV expression is a consequence of transcriptional changes in tumors. HERVs as cancer-specific antigens in hematological cancers appear to be particularly promising. Saini et al. (2020) found HERV-specific T cells are present in 17 of the 34 patients with leukemia, recognizing 29 HERV-derived peptides representing 18 different HERV loci, among which ERVH-5, ERVW-1, and ERVE-3 had the strongest responses [347][174]. Furthermore, the ancestral retroviral HEMO envelope gene (Human Endogenous MER34 ORF) is hailed as a pan-cancer target for leukemia, lung, adrenal, thyroid, breast, ovarian, uterus, cervical, prostate, esophagus, stomach, colon, liver, pancreas, renal, bladder, brain, and skin cancer [348][175]. Vaccinations of mice with HERV epitopes were shown to be safe and able to generate tumor-specific immune cells [219,339,349,350][176][177][178][179].

Furthermore, HERV-H LTR-associating proteins 1 and 2 (HHLA1 and HHLA2) on chromosomes 3q13.13 and 8q24.22 have been shown to carry immune checkpoint functions [353][180]. First described by Mager et al. in 1999, HHLA1 and HHLA2 are both members of the B7 family and obtain their polyadenylation signal through HERV-H LTR regions [354[181][182],355], thus revealing a control mechanism of viral origin [356][183]. While both proteins are part of oncogenic signaling pathways, HHLA2 has been detected in several human cancers [195][184]. HHLA2 was found to be overexpressed in basal breast cancer [357][185], triple-negative breast cancer [357][185], colorectal cancer [358][186], lung cancer [359[187][188][189],360,361], liver cancer [362][190], bladder urothelial carcinoma [363][191], ccRCC [364[192][193][194],365,366], pancreatic cancer [367[195][196][197],368,369], osteosarcoma [370][198], oral squamous cell carcinoma [371][199], and many other cancers [357,364][185][192] compared to adjacent normal tissue or healthy controls. Additionally, elevated HHLA2 protein levels were associated with tumor size, tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, and low relapse-free and overall survival in these cancers [357,358,359,360,361,362,363,364,365,366,367,368,369,370,371][185][186][187][188][189][190][191][192][193][194][195][196][197][198][199].

In summary, HERVs are involved in various homeostatic and pathogenic pathways with potential effects on cancer development and progression. The usage of HERVs themselves as therapeutic agents, as well as the HERV proteins as tumor-specific targets, are promising but must be further evaluated to exclude any undesired side effects.

References

- Hartung, H.-P.; Derfuss, T.; Cree, B.A.; Sormani, M.P.; Selmaj, K.; Stutters, J.; Prados, F.; MacManus, D.; Schneble, H.-M.; Lambert, E.; et al. Efficacy and safety of temelimab in multiple sclerosis: Results of a randomized phase 2b and extension study. Mult. Scler. J. 2022, 28, 429–440.

- Nali, L.H.; Olival, G.S.; Montenegro, H.; da Silva, I.T.; Dias-Neto, E.; Naya, H.; Spangenberg, L.; Penalva-De-Oliveira, A.C.; Romano, C.M. Human endogenous retrovirus and multiple sclerosis: A review and transcriptome findings. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 57, 103383.

- Yao, W.; Zhou, P.; Yan, Q.; Wu, X.; Xia, Y.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Zhu, F. ERVWE1 Reduces Hippocampal Neuron Density and Impairs Dendritic Spine Morphology through Inhibiting Wnt/JNK Non-Canonical Pathway via miR-141-3p in Schizophrenia. Viruses 2023, 15, 168.

- Li, X.; Wu, X.; Li, W.; Yan, Q.; Zhou, P.; Xia, Y.; Yao, W.; Zhu, F. HERV-W ENV Induces Innate Immune Activation and Neuronal Apoptosis via linc01930/cGAS Axis in Recent-Onset Schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3000.

- Curtin, F.; Champion, B.; Davoren, P.; Duke, S.; Ekinci, E.; Gilfillan, C.; Morbey, C.; Nathow, T.; O’Moore-Sullivan, T.; O’Neal, D.; et al. A safety and pharmacodynamics study of temelimab, an antipathogenic human endogenous retrovirus type W envelope monoclonal antibody, in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020, 22, 1111–1121.

- Levet, S.; Charvet, B.; Bertin, A.; Deschaumes, A.; Perron, H.; Hober, D. Human Endogenous Retroviruses and Type 1 Diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2019, 19, 141.

- HERV-E TCR Transduced Autologous T Cells in People With Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Available online: https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03354390 (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Dolei, A.; Uleri, E.; Ibba, G.; Caocci, M.; Piu, C.; Serra, C. The aliens inside human DNA: HERV-W/MSRV/syncytin-1 endogenous retroviruses and neurodegeneration. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2015, 9, 577–587.

- Bannert, N.; Kurth, R. Retroelements and the human genome: New perspectives on an old relation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14572–14579.

- Deininger, P.L.; Batzer, M.A. Mammalian retroelements. Genome Res. 2002, 12, 1455–1465.

- Lindemann, D.; Steffen, I.; Pohlmann, S. Cellular entry of retroviruses. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2013, 790, 128–149.

- Tongyoo, P.; Avihingsanon, Y.; Prom-On, S.; Mutirangura, A.; Mhuantong, W.; Hirankarn, N. EnHERV: Enrichment analysis of specific human endogenous retrovirus patterns and their neighboring genes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177119.

- Kim, H.S. Genomic impact, chromosomal distribution and transcriptional regulation of HERV elements. Mol. Cells 2012, 33, 539–544.

- Crosslin, D.R.; Carrell, D.S.; Burt, A.; Kim, D.S.; Underwood, J.G.; Hanna, D.S.; Comstock, B.A.; Baldwin, E.; de Andrade, M.; Kullo, I.J.; et al. Genetic variation in the HLA region is associated with susceptibility to herpes zoster. Genes Immun. 2015, 16, 1–7.

- Kassiotis, G. Endogenous retroviruses and the development of cancer. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 1343–1349.

- Chuong, E.B.; Elde, N.C.; Feschotte, C. Regulatory activities of transposable elements: From conflicts to benefits. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 71–86.

- Ohnuki, M.; Tanabe, K.; Sutou, K.; Teramoto, I.; Sawamura, Y.; Narita, M.; Nakamura, M.; Tokunaga, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Watanabe, A.; et al. Dynamic regulation of human endogenous retroviruses mediates factor-induced reprogramming and differentiation potential. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 12426–12431.

- Durruthy-Durruthy, J.; Sebastiano, V.; Wossidlo, M.; Cepeda, D.; Cui, J.; Grow, E.J.; Davila, J.; Mall, M.; Wong, W.H.; Wysocka, J.; et al. The primate-specific noncoding RNA HPAT5 regulates pluripotency during human preimplantation development and nuclear reprogramming. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 44–52.

- Frendo, J.-L.; Olivier, D.; Cheynet, V.; Blond, J.-L.; Bouton, O.; Vidaud, M.; Rabreau, M.; Evain-Brion, D.; Mallet, F. Direct Involvement of HERV-W Env Glycoprotein in Human Trophoblast Cell Fusion and Differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 3566–3574.

- Soygur, B.; Sati, L. The role of syncytins in human reproduction and reproductive organ cancers. Reproduction 2016, 152, R167–R178.

- Ting, C.N.; Rosenberg, M.P.; Snow, C.M.; Samuelson, L.C.; Meisler, M.H. Endogenous retroviral sequences are required for tissue-specific expression of a human salivary amylase gene. Genes Dev. 1992, 6, 1457–1465.

- Gogvadze, E.; Stukacheva, E.; Buzdin, A.; Sverdlov, E. Human-specific modulation of transcriptional activity provided by endogenous retroviral insertions. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 6098–6105.

- Emera, D.; Casola, C.; Lynch, V.J.; Wildman, D.E.; Agnew, D.; Wagner, G.P. Convergent Evolution of Endometrial Prolactin Expression in Primates, Mice, and Elephants Through the Independent Recruitment of Transposable Elements. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012, 29, 239–247.

- Suntsova, M.; Garazha, A.; Ivanova, A.; Kaminsky, D.; Zhavoronkov, A.; Buzdin, A. Molecular functions of human endogenous retroviruses in health and disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 3653–3675.

- Tuan, D.; Pi, W. In Human Beta-Globin Gene Locus, ERV-9 LTR Retrotransposon Interacts with and Activates Beta- but Not Gamma-Globin Gene. Blood 2014, 124, 2686.

- Chen, T.; Meng, Z.; Gan, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, F.; Gu, Y.; Xu, X.; Tang, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. The viral oncogene Np9 acts as a critical molecular switch for co-activating β-catenin, ERK, Akt and Notch1 and promoting the growth of human leukemia stem/progenitor cells. Leukemia 2013, 27, 1469–1478.

- Heyne, K.; Kölsch, K.; Bruand, M.; Kremmer, E.; Grässer, F.A.; Mayer, J.; Roemer, K. Np9, a cellular protein of retroviral ancestry restricted to human, chimpanzee and gorilla, binds and regulates ubiquitin ligase MDM2. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 2619–2633.

- Global Cancer Facts & Figures 2021 American Cancer Society. 2021. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2021/cancer-facts-and-figures-2021.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Sledge, G.W.; Mamounas, E.P.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Burstein, H.J.; Goodwin, P.J.; Wolff, A.C. Past, Present, and Future Challenges in Breast Cancer Treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1979–1986.

- Tavakolian, S.; Goudarzi, H.; Faghihloo, E. Evaluating the expression level of HERV-K env, np9, rec and gag in breast tissue. Infect. Agents Cancer 2019, 14, 42.

- Wang-Johanning, F.; Frost, A.R.; Jian, B.; Epp, L.; Lu, D.W.; Johanning, G.L. Quantitation of HERV-K env gene expression and splicing in human breast cancer. Oncogene 2003, 22, 1528–1535.

- Golan, M.; Hizi, A.; Resau, J.H.; Yaal-Hahoshen, N.; Reichman, H.; Keydar, I.; Tsarfaty, I. Human endogenous retrovirus (HERV-K) reverse transcriptase as a breast cancer prognostic marker. Neoplasia 2008, 10, 521–533.

- Zhao, J.; Rycaj, K.; Geng, S.; Li, M.; Plummer, J.B.; Yin, B.; Liu, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; et al. Expression of Human Endogenous Retrovirus Type K Envelope Protein is a Novel Candidate Prognostic Marker for Human Breast Cancer. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 914–922.

- Montesion, M.; Williams, Z.H.; Subramanian, R.P.; Kuperwasser, C.; Coffin, J.M. Promoter expression of HERV-K (HML-2) provirus-derived sequences is related to LTR sequence variation and polymorphic transcription factor binding sites. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 57.

- Saha, A.K.; Mourad, M.; Kaplan, M.H.; Chefetz, I.; Malek, S.N.; Buckanovich, R.; Markovitz, D.M.; Contreras-Galindo, R. The Genomic Landscape of Centromeres in Cancers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11259.

- Wang-Johanning, F.; Radvanyi, L.; Rycaj, K.; Plummer, J.B.; Yan, P.; Sastry, K.J.; Piyathilake, C.J.; Hunt, K.K.; Johanning, G.L. Human endogenous retrovirus K triggers an antigen-specific immune response in breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 5869–5877.

- Panda, A.; De Cubas, A.A.; Stein, M.; Riedlinger, G.; Kra, J.; Mayer, T.; Smith, C.C.; Vincent, B.G.; Serody, J.S.; Beckermann, K.E.; et al. Endogenous retrovirus expression is associated with response to immune checkpoint blockade in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e121522.

- Wang-Johanning, F.; Li, M.; Esteva, F.; Hess, K.R.; Yin, B.; Rycaj, K.; Plummer, J.B.; Garza, J.G.; Ambs, S.; Johanning, G.L. Human endogenous retrovirus type K antibodies and mRNA as serum biomarkers of early-stage breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 587–595.

- Rhyu, D.-W.; Kang, Y.-J.; Ock, M.-S.; Eo, J.-W.; Choi, Y.-H.; Kim, W.-J.; Leem, S.-H.; Yi, J.-M.; Kim, H.-S.; Cha, H.-J. Expression of human endogenous retrovirus env genes in the blood of breast cancer patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 9173–9183.

- Zhou, F.; Li, M.; Wei, Y.; Lin, K.; Lu, Y.; Shen, J.; Johanning, G.L.; Wang-Johanning, F. Activation of HERV-K Env protein is essential for tumorigenesis and metastasis of breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 84093–84117.

- Lemaître, C.; Tsang, J.; Bireau, C.; Heidmann, T.; Dewannieux, M. A human endogenous retrovirus-derived gene that can contribute to oncogenesis by activating the ERK pathway and inducing migration and invasion. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006451.

- Grandi, N.; Tramontano, E. HERV Envelope Proteins: Physiological Role and Pathogenic Potential in Cancer and Autoimmunity. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 462.

- Xie, M.; Hong, C.; Zhang, B.; Lowdon, R.F.; Xing, X.; Li, D.; Zhou, X.; Lee, H.J.; Maire, C.L.; Ligon, K.L.; et al. DNA hypomethylation within specific transposable element families associates with tissue-specific enhancer landscape. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 836–841.

- Armbruester, V.; Sauter, M.; Roemer, K.; Best, B.; Hahn, S.; Nty, A.; Schmid, A.; Philipp, S.; Mueller, A.; Mueller-Lantzsch, N. Np9 Protein of Human Endogenous Retrovirus K Interacts with Ligand of Numb Protein X. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 10310–10319.

- Downey, R.F.; Sullivan, F.J.; Wang-Johanning, F.; Ambs, S.; Giles, F.J.; Glynn, S.A. Human endogenous retrovirus K and cancer: Innocent bystander or tumorigenic accomplice? Int. J. Cancer 2015, 137, 1249–1257.

- Roy, M.; Pear, W.S.; Aster, J.C. The multifaceted role of Notch in cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2007, 17, 52–59.

- Reedijk, M.; Odorcic, S.; Chang, L.; Zhang, H.; Miller, N.; McCready, D.R.; Lockwood, G.; Egan, S.E. High-level Coexpression of JAG1 and NOTCH1 Is Observed in Human Breast Cancer and Is Associated with Poor Overall Survival. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 8530–8537.

- Elenitoba-Johnson, K.S.; Lim, M.S. New Insights into Lymphoma Pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2018, 13, 193–217.

- Cerhan, J.R.; Wallace, R.B.; Folsom, A.R.; Potter, J.D.; Sellers, T.A.; Zheng, W.; Lutz, C.T. Medical history risk factors for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in older women. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1997, 89, 314–318.

- Smedby, K.E.; Vajdic, C.M.; Falster, M.; Engels, E.A.; Martínez-Maza, O.; Turner, J.; Hjalgrim, H.; Vineis, P.; Costantini, A.S.; Bracci, P.M.; et al. Autoimmune disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: A pooled analysis within the InterLymph Consortium. Blood 2008, 111, 4029–4038.

- Cenk, H.; Sarac, G.; Karadağ, N.; Berktas, H.B.; Sahin, I.; Sener, S.; Kisaciik, D.; Kapicioglu, Y. Intravascular lymphoma presenting with paraneoplastic syndrome. Dermatol. Online J. 2020, 26.

- Contreras-Galindo, R.; Kaplan, M.H.; Leissner, P.; Verjat, T.; Ferlenghi, I.; Bagnoli, F.; Giusti, F.; Dosik, M.H.; Hayes, D.F.; Gitlin, S.D.; et al. Human Endogenous Retrovirus K (HML-2) Elements in the Plasma of People with Lymphoma and Breast Cancer. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 9329–9336.

- Kewitz, S.; Staege, M.S. Expression and Regulation of the Endogenous Retrovirus 3 in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Cells. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 179.

- Cohen, M.; Kato, N.; Larsson, E. ERV3 human endogenous provirus mRNAs are expressed in normal and malignant tissues and cells, but not in choriocarcinoma tumor cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 1988, 36, 121–128.

- Lin, L.; Xu, B.; Rote, N.S. The cellular mechanism by which the human endogenous retrovirus ERV-3 env gene affects proliferation and differentiation in a human placental trophoblast model, BeWo. Placenta 2000, 21, 73–78.

- Larsson, E.; Venables, P.; Andersson, A.C.; Fan, W.; Rigby, S.; Botling, J.; Oberg, F.; Cohen, M.; Nilsson, K. Tissue and differentiation specific expression on the endogenous retrovirus ERV3 (HERV-R) in normal human tissues and during induced monocytic differentiation in the U-937 cell line. Leukemia 1997, 11 (Suppl. S3), 142–144.

- Åbrink, M.; Larsson, E.; Hellman, L. Demethylation of ERV3, an endogenous retrovirus regulating the Kruppel-related zinc finger gene H-plk, in several human cell lines arrested during early monocyte development. DNA Cell Biol. 1998, 17, 27–37.

- Huff, L.M.; Wang, Z.; Iglesias, A.; Fojo, T.; Lee, J.-S. Aberrant transcription from an unrelated promoter can result in MDR-1 expression following drug selection in vitro and in relapsed lymphoma samples. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 11694–11703.

- Daskalakis, M.; Brocks, D.; Sheng, Y.-H.; Islam, S.; Ressnerova, A.; Assenov, Y.; Milde, T.; Oehme, I.; Witt, O.; Goyal, A.; et al. Reactivation of endogenous retroviral elements via treatment with DNMT- and HDAC-inhibitors. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 811–822.

- Scheurer, M.E.; Lupo, P.J.; Bondy, M.L. Epidemiology of childhood cancer. In Principles and Practices of Pediatric Oncology, 7th ed.; Pizzo, P.A., Poplack, D.G., Eds.; Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016.

- Lawrence, M.S.; Stojanov, P.; Polak, P.; Kryukov, G.V.; Cibulskis, K.; Sivachenko, A.; Carter, S.L.; Stewart, C.; Mermel, C.H.; Roberts, S.A.; et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature 2013, 499, 214–218.

- Wahbi, K.; Hayette, S.; Callanan, M.; Gadoux, M.; Charrin, C.; Magaud, J.-P.; Rimokh, R. Involvement of a human endogenous retroviral sequence (THE-7) in a t(7;14)(q21;q32) chromosomal translocation associated with a B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 1997, 11, 1214–1219.

- Guasch, G.; Popovici, C.; Mugneret, F.; Chaffanet, M.; Pontarotti, P.; Birnbaum, D.; Pébusque, M.-J. Endogenous retroviral sequence is fused to FGFR1 kinase in the 8p12 stem-cell myeloproliferative disorder with t(8;19)(p12;q13.3). Blood 2003, 101, 286–288.

- Mugneret, F.; Chaffanet, M.; Maynadie, M.; Guasch, G.; Favre, B.; Casasnovas, O.; Birnbaum, D.; Pebusque, M.-J. The 8p12 myeloproliferative disorder. t(8;19)(p12;q13.3): A novel translocation involving the FGFR1 gene. Br. J. Haematol. 2000, 111, 647–649.

- Schmidt, K.L.; Vangsted, A.J.; Hansen, B.; Vogel, U.B.; Hermansen, N.E.U.; Jensen, S.B.; Laska, M.J.; Nexø, B.A. Synergy of two human endogenous retroviruses in multiple myeloma. Leuk. Res. 2015, 39, 1125–1128.

- Kaplan, M.H.; Kaminski, M.; Estes, J.M.; Gitlin, S.D.; Zahn, J.; Elder, J.T.; Tejasvi, T.; Gensterblum, E.; Sawalha, A.H.; McGowan, J.P.; et al. Structural variation of centromeric endogenous retroviruses in human populations and their impact on cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Sézary syndrome, and HIV infection. BMC Med. Genom. 2019, 12, 58.

- Morozov, V.A.; Thi, V.L.D.; Denner, J. The transmembrane protein of the human endogenous retrovirus--K (HERV-K) modulates cytokine release and gene expression. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70399.

- Couper, K.N.; Blount, D.G.; Riley, E.M. IL-10: The master regulator of immunity to infection. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 5771–5777.

- Renaudineau, Y.; Hillion, S.; Saraux, A.; Mageed, R.A.; Youinou, P. An alternative exon 1 of the CD5 gene regulates CD5 expression in human B lymphocytes. Blood 2005, 106, 2781–2789.

- Schmitt, K.; Reichrath, J.; Roesch, A.; Meese, E.; Mayer, J. Transcriptional profiling of human endogenous retrovirus group HERV-K(HML-2) loci in melanoma. Genome Biol. Evol. 2013, 5, 307–328.

- Reiche, J.; Pauli, G.; Ellerbrok, H. Differential expression of human endogenous retrovirus K transcripts in primary human melanocytes and melanoma cell lines after UV irradiation. Melanoma Res. 2010, 20, 435–440.

- Schanab, O.; Humer, J.; Gleiss, A.; Mikula, M.; Sturlan, S.; Grunt, S.; Okamoto, I.; Muster, T.; Pehamberger, H.; Waltenberger, A. Expression of human endogenous retrovirus K is stimulated by ultraviolet radiation in melanoma. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2011, 24, 656–665.

- Hohenadl, C.; Germaier, H.; Walchner, M.; Hagenhofer, M.; Herrmann, M.; Stürzl, M.; Kind, P.; Hehlmann, R.; Erfle, V.; Leib-Mösch, C. Transcriptional activation of endogenous retroviral sequences in human epidermal keratinocytes by UVB irradiation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1999, 113, 587–594.

- Schön, U.; Seifarth, W.; Baust, C.; Hohenadl, C.; Erfle, V.; Leib-Mösch, C. Cell type-specific expression and promoter activity of human endogenous retroviral long terminal repeats. Virology 2001, 279, 280–291.

- Golob, M.; Buettner, R.; Bosserhoff, A. Characterization of a Transcription Factor Binding Site, Specifically Activating MIA Transcription in Melanoma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2000, 115, 42–47.

- Glinsky, G.V. Transposable Elements and DNA Methylation Create in Embryonic Stem Cells Human-Specific Regulatory Sequences Associated with Distal Enhancers and Noncoding RNAs. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015, 7, 1432–1454.

- Wang, T.; Zeng, J.; Lowe, C.B.; Sellers, R.G.; Salama, S.R.; Yang, M.; Burgess, S.M.; Brachmann, R.K.; Haussler, D. Species-specific endogenous retroviruses shape the transcriptional network of the human tumor suppressor protein p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 18613–18618.

- Bao, F.; LoVerso, P.R.; Fisk, J.N.; Zhurkin, V.B.; Cui, F. p53 binding sites in normal and cancer cells are characterized by distinct chromatin context. Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 2073–2085.

- Chang, N.-T.; Yang, W.K.; Huang, H.-C.; Yeh, K.-W.; Wu, C.-W. The transcriptional activity of HERV-I LTR is negatively regulated by its cis-elements and wild type p53 tumor suppressor protein. J. Biomed. Sci. 2007, 14, 211–222.

- Jacques, P.; Jeyakani, J.; Bourque, G. The Majority of Primate-Specific Regulatory Sequences Are Derived from Transposable Elements. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003504.

- Babaian, A.; Mager, D.L. Endogenous retroviral promoter exaptation in human cancer. Mob. DNA 2016, 7, 24.

- Flockhart, R.J.; Webster, D.E.; Qu, K.; Mascarenhas, N.; Kovalski, J.; Kretz, M.; Khavari, P.A. BRAFV600E remodels the melanocyte transcriptome and induces BANCR to regulate melanoma cell migration. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1006–1014.

- Leucci, E.; Vendramin, R.; Spinazzi, M.; Laurette, P.; Fiers, M.; Wouters, J.; Radaelli, E.; Eyckerman, S.; Leonelli, C.; Vanderheyden, K.; et al. Melanoma addiction to the long non-coding RNA SAMMSON. Nature 2016, 531, 518–522.

- Kalter, S.S.; Helmke, R.J.; Heberling, R.L.; Panigel, M.; Fowler, A.K.; Strickland, J.E.; Hellman, A. Brief communication: C-type particles in normal human placentas. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1973, 50, 1081–1084.

- Bronson, D.L.; Ritzi, D.M.; Fraley, E.E.; Dalton, A.J. Morphologic evidence for retrovirus production by epithelial cells derived from a human testicular tumor metastasis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1978, 60, 1305–1308.

- Boller, K.; Janssen, O.; Schuldes, H.; Tönjes, R.R.; Kurth, R. Characterization of the antibody response specific for the human endogenous retrovirus HTDV/HERV-K. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 4581–4588.

- Ruprecht, K.; Ferreira, H.; Flockerzi, A.; Wahl, S.; Sauter, M.; Mayer, J.; Mueller-Lantzsch, N. Human endogenous retrovirus family HERV-K(HML-2) RNA transcripts are selectively packaged into retroviral particles produced by the human germ cell tumor line Tera-1 and originate mainly from a provirus on chromosome 22q11.21. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 10008–10016.

- Boller, K.; Schönfeld, K.; Lischer, S.; Fischer, N.; Hoffmann, A.; Kurth, R.; Tönjes, R.R. Human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K113 is capable of producing intact viral particles. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 567–572.

- Knössl, M.; Löwer, R.; Löwer, J. Expression of the human endogenous retrovirus HTDV/HERV-K is enhanced by cellular transcription factor YY1. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 1254–1261.

- Ruda, V.M.; Akopov, S.B.; Trubetskoy, D.O.; Manuylov, N.L.; Vetchinova, A.S.; Zavalova, L.L.; Nikolaev, L.G.; Sverdlov, E.D. Tissue specificity of enhancer and promoter activities of a HERV-K(HML-2) LTR. Virus Res. 2004, 104, 11–16.

- Rakoff-Nahoum, S.; Kuebler, P.J.; Heymann, J.J.; Sheehy, M.E.; Ortiz, G.M.; Ogg, G.S.; Barbour, J.D.; Lenz, J.; Steinfeld, A.D.; Nixon, D.F. Detection of T lymphocytes specific for human endogenous retrovirus K (HERV-K) in patients with seminoma. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2006, 22, 52–56.

- Löwer, R.; Tönjes, R.R.; Korbmacher, C.; Kurth, R.; Löwer, J. Identification of a Rev-related protein by analysis of spliced transcripts of the human endogenous retroviruses HTDV/HERV-K. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 141–149.

- Boese, A.; Sauter, M.; Galli, U.; Best, B.; Herbst, H.; Mayer, J.; Kremmer, E.; Roemer, K.; Mueller-Lantzsch, N. Human endogenous retrovirus protein cORF supports cell transformation and associates with the promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein. Oncogene 2000, 19, 4328–4336.

- Armbruester, V.; Sauter, M.; Krautkraemer, E.; Meese, E.; Kleiman, A.; Best, B.; Roemer, K.; Mueller-Lantzsch, N. A novel gene from the human endogenous retrovirus K expressed in transformed cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002, 8, 1800–1807.

- Magin-Lachmann, C.; Hahn, S.; Strobel, H.; Held, U.; Löwer, J.; Löwer, R. Rec (formerly Corf) function requires interaction with a complex, folded RNA structure within its responsive element rather than binding to a discrete specific binding site. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 10359–10371.

- Denne, M.; Sauter, M.; Armbruester, V.; Licht, J.D.; Roemer, K.; Mueller-Lantzsch, N. Physical and functional interactions of human endogenous retrovirus proteins Np9 and rec with the promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 5607–5616.

- Eisenhauer, E.A. Real-world evidence in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, viii61–viii65.

- Torre, L.A.; Trabert, B.; DeSantis, C.E.; Miller, K.D.; Samimi, G.; Runowicz, C.D.; Gaudet, M.M.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 284–296.

- Heidmann, O.; Béguin, A.; Paternina, J.; Berthier, R.; Deloger, M.; Bawa, O.; Heidmann, T. HEMO, an ancestral endogenous retroviral envelope protein shed in the blood of pregnant women and expressed in pluripotent stem cells and tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6642–E6651.

- Menendez, L.; Benigno, B.B.; McDonald, J.F. L1 and HERV-W retrotransposons are hypomethylated in human ovarian carcinomas. Mol. Cancer 2004, 3, 12.

- Iramaneerat, K.; Rattanatunyong, P.; Khemapech, N.; Triratanachat, S.; Mutirangura, A. HERV-K hypomethylation in ovarian clear cell carcinoma is associated with a poor prognosis and platinum resistance. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2011, 21, 51–57.

- Lavie, L.; Kitova, M.; Maldener, E.; Meese, E.; Mayer, J. CpG methylation directly regulates transcriptional activity of the human endogenous retrovirus family HERV-K(HML-2). J. Virol. 2005, 79, 876–883.

- Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Zhu, F. Human Endogenous Retroviral Envelope Protein Syncytin-1 and Inflammatory Abnormalities in Neuropsychological Diseases. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 422.

- Ball, M.; Carmody, M.; Wynne, F.; Dockery, P.; Aigner, A.; Cameron, I.; Higgins, J.; Smith, S.; Aplin, J.; Moore, T. Expression of pleiotrophin and its receptors in human placenta suggests roles in trophoblast life cycle and angiogenesis. Placenta 2009, 30, 649–653.

- Schulte, A.M.; Lai, S.; Kurtz, A.; Czubayko, F.; Riegel, A.T.; Wellstein, A. Human trophoblast and choriocarcinoma expression of the growth factor pleiotrophin attributable to germ-line insertion of an endogenous retrovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 14759–14764.

- Schulte, A.M.; Malerczyk, C.; Cabal-Manzano, R.; Gajarsa, J.J.; List, H.-J.; Riegel, A.T.; Wellstein, A. Influence of the human endogenous retrovirus-like element HERV-E.PTN on the expression of growth factor pleiotrophin: A critical role of a retroviral Sp1-binding site. Oncogene 2000, 19, 3988–3998.

- Weinberg, B.A.; Marshall, J.L.; Salem, M.E. The Growing Challenge of Young Adults With Colorectal Cancer. Oncology 2017, 31, 381–389.

- Bannert, N.; Kurth, R. The Evolutionary Dynamics of Human Endogenous Retroviral Families. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2006, 7, 149–173.

- Wang, K.; Karin, M. Tumor-Elicited Inflammation and Colorectal Cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2015, 128, 173–196.

- Lock, F.E.; Babaian, A.; Zhang, Y.; Gagnier, L.; Kuah, S.; Weberling, A.; Karimi, M.M.; Mager, D.L. A novel isoform of IL-33 revealed by screening for transposable element promoted genes in human colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180659.

- Miller, A.M. Role of IL-33 in inflammation and disease. J. Inflamm. 2011, 8, 22.

- Cui, G.; Qi, H.; Gundersen, M.D.; Yang, H.; Christiansen, I.; Sørbye, S.W.; Goll, R.; Florholmen, J. Dynamics of the IL-33/ST2 network in the progression of human colorectal adenoma to sporadic colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2015, 64, 181–190.

- Rajagopalan, D.; Magallanes, R.T.; Bhatia, S.S.; Teo, W.S.; Sian, S.; Hora, S.; Lee, K.K.; Zhang, Y.; Jadhav, S.P.; Wu, Y.; et al. TIP60 represses activation of endogenous retroviral elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 9456–9470.

- Gibb, E.A.; Warren, R.L.; Wilson, G.W.; Brown, S.D.; Robertson, G.A.; Morin, G.B.; Holt, R.A. Activation of an endogenous retrovirus-associated long non-coding RNA in human adenocarcinoma. Genome Med. 2015, 7, 22.

- Kaller, M.; Götz, U.; Hermeking, H. Loss of p53-inducible long non-coding RNA LINC01021 increases chemosensitivity. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 102783–102800.

- Li, X.L.; Subramanian, M.; Jones, M.F.; Chaudhary, R.; Singh, D.K.; Zong, X.; Gryder, B.; Sindri, S.; Mo, M.; Schetter, A.; et al. Long Noncoding RNA PURPL Suppresses Basal p53 Levels and Promotes Tumorigenicity in Colorectal Cancer. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 2408–2423.

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2022. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Ahn, K.; Kim, H.-S. Structural and quantitative expression analyses of HERV gene family in human tissues. Mol. Cells 2009, 28, 99–103.

- Liang, Q.; Ding, J.; Xu, R.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, S. Identification of a novel human endogenous retrovirus and promoter activity of its 5’ U3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 382, 468–472.

- Reis, B.S.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Frosina, D.; Holz, M.; Ritter, E.; Nakayama, E.; Ishida, T.; Obata, Y.; Carver, B.; Scher, H.; et al. Prostate Cancer Progression Correlates with Increased Humoral Immune Response to a Human Endogenous Retrovirus GAG Protein. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 6112–6125.

- Ma, W.; Hong, Z.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Ding, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, F.; Yuan, Y. Human Endogenous Retroviruses-K (HML-2) Expression Is Correlated with Prognosis and Progress of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 8201642.

- Ko, E.-J.; Ock, M.-S.; Choi, Y.-H.; Iovanna, J.; Mun, S.; Han, K.; Kim, H.-S.; Cha, H.-J. Human Endogenous Retrovirus (HERV)-K env Gene Knockout Affects Tumorigenic Characteristics of nupr1 Gene in DLD-1 Colorectal Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3941.

- Hashimoto, K.; Suzuki, A.M.; Dos Santos, A.; Desterke, C.; Collino, A.; Ghisletti, S.; Braun, E.; Bonetti, A.; Fort, A.; Qin, X.-Y.; et al. CAGE profiling of ncRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma reveals widespread activation of retroviral LTR promoters in virus-induced tumors. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1812–1824.

- Liu, F.; Hou, W.; Liang, J.; Zhu, L.; Luo, C. LRP1B mutation: A novel independent prognostic factor and a predictive tumor mutation burden in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 4039–4048.

- Lu, X.; Sachs, F.; Ramsay, L.; Jacques, P.; Göke, J.; Bourque, G.; Ng, H.-H. The retrovirus HERVH is a long noncoding RNA required for human embryonic stem cell identity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 423–425.

- Ishida, T.; Obata, Y.; Ohara, N.; Matsushita, H.; Sato, S.; Uenaka, A.; Saika, T.; Miyamura, T.; Chayama, K.; Nakamura, Y.; et al. Identification of the HERV-K gag antigen in prostate cancer by SEREX using autologous patient serum and its immunogenicity. Cancer Immun. 2008, 8, 15.

- Gruchot, J.; Kremer, D.; Küry, P. Neural Cell Responses Upon Exposure to Human Endogenous Retroviruses. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 655.

- Dolei, A.; Ibba, G.; Piu, C.; Serra, C. Expression of HERV Genes as Possible Biomarker and Target in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3706.

- Misra, A.; Chosdol, K.; Sarkar, C.; Mahapatra, A.K.; Sinha, S. Alteration of a sequence with homology to human endogenous retrovirus (HERV-K) in primary human glioma: Implications for viral repeat mediated rearrangement. Mutat. Res. 2001, 484, 53–59.

- Abrarova, N.; Simonova, L.; Vinogradova, T.; Sverdlov, E. Different transcription activity of HERV-K LTR-containing and LTR-lacking genes of the KIAA1245/NBPF gene subfamily. Genetica 2011, 139, 733–741.

- Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Yu, H.; Zeng, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, F. Activation of elements in HERV-W family by caffeine and aspirin. Virus Genes 2013, 47, 219–227.

- Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Yin, S.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, F. Human endogenous retrovirus W family envelope gene activates the small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel in human neuroblastoma cells through CREB. Neuroscience 2013, 247, 164–174.

- Chen, Y.; Yan, Q.; Zhou, P.; Li, S.; Zhu, F. HERV-W env regulates calcium influx via activating TRPC3 channel together with depressing DISC1 in human neuroblastoma cells. J. NeuroVirology 2019, 25, 101–113.

- Tomlins, S.A.; Laxman, B.; Dhanasekaran, S.M.; Helgeson, B.E.; Cao, X.; Morris, D.S.; Menon, A.; Jing, X.; Cao, Q.; Han, B.; et al. Distinct classes of chromosomal rearrangements create oncogenic ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer. Nature 2007, 448, 595–599.

- Hermans, K.G.; van der Korput, H.A.; van Marion, R.; van de Wijngaart, D.J.; der Made, A.Z.-V.; Dits, N.F.; Boormans, J.L.; van der Kwast, T.H.; van Dekken, H.; Bangma, C.H.; et al. Truncated ETV1, Fused to Novel Tissue-Specific Genes, and Full-Length ETV1 in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 7541–7549.

- Schiavetti, F.; Thonnard, J.; Colau, D.; Boon, T.; Coulie, P.G. A human endogenous retroviral sequence encoding an antigen recognized on melanoma by cytolytic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 5510–5516.

- Goering, W.; Ribarska, T.; Schulz, W. Selective changes of retroelement expression in human prostate cancer. Carcinogenesis 2011, 32, 1484–1492.

- Lawrence, M.G.; Stephens, C.R.; Need, E.F.; Lai, J.; Buchanan, G.; Clements, J.A. Long terminal repeats act as androgen-responsive enhancers for the PSA-kallikrein locus. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3199–3210.

- Lawrence, M.G.; Lai, J.; Clements, J. Kallikreins on steroids: Structure, function, and hormonal regulation of prostate-specific antigen and the extended kallikrein locus. Endocr. Rev. 2010, 31, 407–446.

- Kaufmann, S.; Sauter, M.; Schmitt, M.; Baumert, B.; Best, B.; Boese, A.; Roemer, K.; Mueller-Lantzsch, N. Human endogenous retrovirus protein Rec interacts with the testicular zinc-finger protein and androgen receptor. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 1494–1502.

- Gabriel, U.; Steidler, A.; Trojan, L.; Michel, M.S.; Seifarth, W.; Fabarius, A.; Hanke, K.; Hohn, O.; Bannert, N.; Ohishi, T.; et al. Smoking increases transcription of human endogenous retroviruses in a newly established in vitro cell model and in normal urothelium. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2010, 26, 883–888.

- Kahyo, T.; Tao, H.; Shinmura, K.; Yamada, H.; Mori, H.; Funai, K.; Kurabe, N.; Suzuki, M.; Tanahashi, M.; Niwa, H.; et al. Identification and association study with lung cancer for novel insertion polymorphisms of human endogenous retrovirus. Carcinogenesis 2013, 34, 2531–2538.

- Kawamoto, S.; Hashizume, S.; Katakura, Y.; Tachibana, H.; Murakami, H. Molecular cloning of yeast cytochrome c-like polypeptide expressed in human lung carcinoma: An antigen recognizable by lung cancer-specific human monoclonal antibody. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Anim. 1995, 31, 724–729.

- Ito, J.; Kimura, I.; Soper, A.; Coudray, A.; Koyanagi, Y.; Nakaoka, H.; Inoue, I.; Turelli, P.; Trono, D.; Sato, K. Endogenous retroviruses drive KRAB zinc-finger protein family expression for tumor suppression. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc3020.

- Wang, Y.; Xue, H.; Aglave, M.; Lainé, A.; Gallopin, M.; Gautheret, D. The contribution of uncharted RNA sequences to tumor identity in lung adenocarcinoma. NAR Cancer 2022, 4, zcac001.

- Liu, M.; Ohtani, H.; Zhou, W.; Ørskov, A.D.; Charlet, J.; Zhang, Y.W.; Shen, H.; Baylin, S.B.; Liang, G.; Grønbæk, K.; et al. Vitamin C increases viral mimicry induced by 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10238–10244.

- Roulois, D.; Loo Yau, H.; Singhania, R.; Wang, Y.; Danesh, A.; Shen, S.Y.; Han, H.; Liang, G.; Jones, P.A.; Pugh, T.J.; et al. DNA-Demethylating Agents Target Colorectal Cancer Cells by Inducing Viral Mimicry by Endogenous Transcripts. Cell 2015, 162, 961–973.

- Liu, M.; Thomas, S.L.; DeWitt, A.K.; Zhou, W.; Madaj, Z.B.; Ohtani, H.; Baylin, S.B.; Liang, G.; Jones, P.A. Dual Inhibition of DNA and Histone Methyltransferases Increases Viral Mimicry in Ovarian Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 5754–5766.

- Zhao, H.; Ning, S.; Nolley, R.; Scicinski, J.; Oronsky, B.; Knox, S.J.; Peehl, D.M. The immunomodulatory anticancer agent, RRx-001, induces an interferon response through epigenetic induction of viral mimicry. Clin. Epigenetics 2017, 9, 4.

- Kim, J.W.; Eder, J.P. Prospects for targeting PD-1 and PD-L1 in various tumor types. Oncology 2014, 28 (Suppl. S3), 15–28.

- Motzer, R.J.; Escudier, B.; McDermott, D.F.; George, S.; Hammers, H.J.; Srinivas, S.; Tykodi, S.S.; Sosman, J.A.; Procopio, G.; Plimack, E.R.; et al. Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1803–1813.

- Solovyov, A.; Vabret, N.; Arora, K.S.; Snyder, A.; Funt, S.A.; Bajorin, D.F.; Rosenberg, J.E.; Bhardwaj, N.; Ting, D.T.; Greenbaum, B.D. Global Cancer Transcriptome Quantifies Repeat Element Polarization between Immunotherapy Responsive and T Cell Suppressive Classes. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 512–521.

- LaFave, L.M.; Béguelin, W.; Koche, R.; Teater, M.; Spitzer, B.; Chramiec, A.; Papalexi, E.; Keller, M.D.; Hricik, T.; Konstantinoff, K.; et al. Loss of BAP1 function leads to EZH2-dependent transformation. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1344–1349.

- Cherkasova, E.E.; Malinzak, E.E.; Rao, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Senchenko, V.N.; Kudryavtseva, A.V.; Nickerson, M.L.; Merino, M.; Hong, J.A.; Schrump, D.S.; et al. Inactivation of the von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor leads to selective expression of a human endogenous retrovirus in kidney cancer. Oncogene 2011, 30, 4697–4706.

- Rajabi, S.; Dehghan, M.H.; Dastmalchi, R.; Mashayekhi, F.J.; Salami, S.; Hedayati, M. The roles and role-players in thyroid cancer angiogenesis. Endocr. J. 2019, 66, 277–293.

- Pellegriti, G.; Frasca, F.; Regalbuto, C.; Squatrito, S.; Vigneri, R. Worldwide Increasing Incidence of Thyroid Cancer: Update on Epidemiology and Risk Factors. J. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013, 2013, 965212.

- Smallridge, R.C.; Marlow, L.; Copland, J.A. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: Molecular pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2009, 16, 17–44.

- Rodgers, S.E.; Evans, D.B.; Lee, J.E.; Perrier, N.D. Adrenocortical carcinoma. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2006, 15, 535–553.

- Zheng, G.; Zhang, H.; Hao, S.; Liu, C.; Xu, J.; Ning, J.; Wu, G.; Jiang, L.; Li, G.; Zheng, H.; et al. Patterns and clinical significance of cervical lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer patients with Delphian lymph node metastasis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 57089–57098.

- Fogel, E.L.; Shahda, S.; Sandrasegaran, K.; DeWitt, J.; Easler, J.J.; Agarwal, D.M.; Eagleson, M.; Zyromski, N.J.; House, M.G.; Ellsworth, S.; et al. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Pancreas Cancer in 2016: A Review. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 537–554.

- Li, M.; Radvanyi, L.; Yin, B.; Rycaj, K.; Li, J.; Chivukula, R.; Lin, K.; Lu, Y.; Shen, J.; Chang, D.Z.; et al. Downregulation of Human Endogenous Retrovirus Type K (HERV-K) Viral env RNA in Pancreatic Cancer Cells Decreases Cell Proliferation and Tumor Growth. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5892–5911.

- Rigogliuso, G.; Biniossek, M.L.; Goodier, J.L.; Mayer, B.; Pereira, G.C.; Schilling, O.; Meese, E.; Mayer, J. A human endogenous retrovirus encoded protease potentially cleaves numerous cellular proteins. Mob. DNA 2019, 10, 36.

- De Parseval, N.; Françoiscasellaa, J.; Gressinb, L.; Heidmann, T. Characterization of the three HERV-H proviruses with an open envelope reading frame encompassing the immunosuppressive domain and evolutionary history in primates. Virology 2001, 279, 558–569.

- Kudo-Saito, C.; Yura, M.; Yamamoto, R.; Kawakami, Y. Induction of immunoregulatory CD271+ cells by metastatic tumor cells that express human endogenous retrovirus H. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1361–1370.

- Ho, X.D.; Nguyen, H.G.; Trinh, L.H.; Reimann, E.; Prans, E.; Kõks, G.; Maasalu, K.; Le, V.Q.; Nguyen, V.H.; Le, N.T.N.; et al. Analysis of the Expression of Repetitive DNA Elements in Osteosarcoma. Front. Genet. 2017, 8, 193.

- Michna, A.; Schötz, U.; Selmansberger, M.; Zitzelsberger, H.; Lauber, K.; Unger, K.; Hess, J. Transcriptomic analyses of the radiation response in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma subclones with different radiation sensitivity: Time-course gene expression profiles and gene association networks. Radiat. Oncol. 2016, 11, 94.

- Rothenberg, S.M.; Ellisen, L.W. The molecular pathogenesis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 1951–1957.

- Yamamoto, V.N.; Thylur, D.S.; Bauschard, M.; Schmale, I.; Sinha, U.K. Overcoming radioresistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2016, 63, 44–51.

- Liang, Q.; Ding, J.; Xu, R.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, S. The novel human endogenous retrovirus-related gene, psiTPTE22-HERV, is silenced by DNA methylation in cancers. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 127, 1833–1843.

- Johanning, G.L.; Malouf, G.G.; Zheng, X.; Esteva, F.J.; Weinstein, J.N.; Wang-Johanning, F.; Su, X. Expression of human endogenous retrovirus-K is strongly associated with the basal-like breast cancer phenotype. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41960.

- Mullins, C.S.; Linnebacher, M. Human endogenous retroviruses and cancer: Causality and therapeutic possibilities. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 6027–6035.

- Dai, L.; Del Valle, L.; Miley, W.; Whitby, D.; Ochoa, A.C.; Flemington, E.K.; Qin, Z. Transactivation of human endogenous retrovirus K (HERV-K) by KSHV promotes Kaposi’s sarcoma development. Oncogene 2018, 37, 4534–4545.

- Jia, L.; Wang, H.; Qu, S.; Miao, X.; Zhang, J. CD147 regulates vascular endothelial growth factor-A expression, tumorigenicity, and chemosensitivity to curcumin in hepatocellular carcinoma. IUBMB Life 2008, 60, 57–63.

- Saini, S.K.; Ørskov, A.D.; Bjerregaard, A.-M.; Unnikrishnan, A.; Holmberg-Thydén, S.; Borch, A.; Jensen, K.V.; Anande, G.; Bentzen, A.K.; Marquard, A.M.; et al. Human endogenous retroviruses form a reservoir of T cell targets in hematological cancers. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5660.

- Kasperek, A.; Béguin, A.; Bawa, O.; De Azevedo, K.; Job, B.; Massard, C.; Scoazec, J.; Heidmann, T.; Heidmann, O. Therapeutic potential of the human endogenous retroviral envelope protein HEMO: A pan-cancer analysis. Mol. Oncol. 2022, 16, 1451–1473.

- Mullins, C.S.; Linnebacher, M. Endogenous retrovirus sequences as a novel class of tumor-specific antigens: An example of HERV-H env encoding strong CTL epitopes. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2012, 61, 1093–1100.

- Probst, P.; Stringhini, M.; Ritz, D.; Fugmann, T.; Neri, D. Antibody-based Delivery of TNF to the Tumor Neovasculature Potentiates the Therapeutic Activity of a Peptide Anticancer Vaccine. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 698–709.

- Sacha, J.B.; Kim, I.-J.; Chen, L.; Ullah, J.H.; Goodwin, D.A.; Simmons, H.A.; Schenkman, D.I.; von Pelchrzim, F.; Gifford, R.J.; Nimityongskul, F.A.; et al. Vaccination with cancer- and HIV infection-associated endogenous retrotransposable elements is safe and immunogenic. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 1467–1479.

- Kraus, B.; Fischer, K.; Sliva, K.; Schnierle, B.S. Vaccination directed against the human endogenous retrovirus-K (HERV-K) gag protein slows HERV-K gag expressing cell growth in a murine model system. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 58.

- Zhao, R.; Chinai, J.M.; Buhl, S.; Scandiuzzi, L.; Ray, A.; Jeon, H.; Ohaegbulam, K.C.; Ghosh, K.; Zhao, A.; Scharff, M.D.; et al. HHLA2 is a member of the B7 family and inhibits human CD4 and CD8 T-cell function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9879–9884.

- Sugimoto, J.; Sugimoto, M.; Bernstein, H.; Jinno, Y.; Schust, D. A novel human endogenous retroviral protein inhibits cell-cell fusion. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 01462.

- Malfavon-Borja, R.; Feschotte, C. Fighting Fire with Fire: Endogenous Retrovirus Envelopes as Restriction Factors. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 4047–4050.

- Mager, D.L.; Hunter, D.; Schertzer, M.; Freeman, J. Endogenous Retroviruses Provide the Primary Polyadenylation Signal for Two New Human Genes (HHLA2 and HHLA3). Genomics 1999, 59, 255–263.

- Kowalski, P.E.; Freeman, J.; Mager, D. Intergenic splicing between a HERV-H endogenous retrovirus and two adjacent human genes. Genomics 1999, 57, 371–379.

- Janakiram, M.; Chinai, J.M.; Fineberg, S.; Fiser, A.; Montagna, C.; Medavarapu, R.; Castano, E.; Jeon, H.; Ohaegbulam, K.C.; Zhao, R.; et al. Expression, Clinical Significance, and Receptor Identification of the Newest B7 Family Member HHLA2 Protein. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 2359–2366.

- Zhu, Z.; Dong, W. Overexpression of HHLA2, a member of the B7 family, is associated with worse survival in human colorectal carcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 11, 1563–1570.

- Cheng, H.; Borczuk, A.; Janakiram, M.; Ren, X.; Lin, J.; Assal, A.; Halmos, B.; Perez-Soler, R.; Zang, X. Wide Expression and Significance of Alternative Immune Checkpoint Molecules, B7x and HHLA2, in PD-L1-Negative Human Lung Cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1954–1964.

- Cheng, H.; Janakiram, M.; Borczuk, A.; Lin, J.; Qiu, W.; Liu, H.; Chinai, J.M.; Halmos, B.; Perez-Soler, R.; Zang, X. HHLA2, a New Immune Checkpoint Member of the B7 Family, Is Widely Expressed in Human Lung Cancer and Associated with EGFR Mutational Status. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 825–832.

- Farrag, M.S.; Ibrahim, E.M.; El-Hadidy, T.A.; Akl, M.F.; Elsergany, A.R.; Abdelwahab, H.W. Human Endogenous Retrovirus-H Long Terminal Repeat- Associating Protein 2 (HHLA2) is a Novel Immune Checkpoint Protein in Lung Cancer which Predicts Survival. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 1883–1889.

- Jing, C.-Y.; Fu, Y.-P.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, M.-X.; Zheng, S.-S.; Huang, J.-L.; Gan, W.; Xu, X.; Lin, J.-J.; Zhang, J.; et al. HHLA2 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: An immune checkpoint with prognostic significance and wider expression compared with PD-L1. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 77.

- Lin, G.; Ye, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C. Immune Checkpoint Human Endogenous Retrovirus-H Long Terminal Repeat-Associating Protein 2 is Upregulated and Independently Predicts Unfavorable Prognosis in Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma. Nephron 2019, 141, 256–264.

- Wang, B.; Ran, Z.; Liu, M.; Ou, Y. Prognostic Significance of Potential Immune Checkpoint Member HHLA2 in Human Tumors: A Comprehensive Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1573.

- Chen, D.; Chen, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Xiao, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, S.; Cao, C.; Xu, X. Upregulated immune checkpoint HHLA2 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: A novel prognostic biomarker and potential therapeutic target. J. Med. Genet. 2019, 56, 43–49.

- Chen, L.; Zhu, D.; Feng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Feng, H.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, J. Overexpression of HHLA2 in human clear cell renal cell carcinoma is significantly associated with poor survival of the patients. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 101.

- Yan, H.; Qiu, W.; de Gonzalez, A.K.K.; Wei, J.-S.; Tu, M.; Xi, C.-H.; Yang, Y.-R.; Peng, Y.-P.; Tsai, W.-Y.; Remotti, H.E.; et al. HHLA2 is a novel immune checkpoint protein in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and predicts post-surgical survival. Cancer Lett. 2019, 442, 333–340.

- Byers, J.T.; Paniccia, A.; Kaplan, J.; Koenig, M.; Kahn, N.; Wilson, L.; Chen, L.; Schulick, R.D.; Edil, B.H.; Zhu, Y. Expression of the Novel Costimulatory Molecule B7-H5 in Pancreatic Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22 (Suppl. S3), S1574–S1579.

- Yuan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Soto, C.; Jiang, X.; An, Z.; Zheng, W. Human Endogenous Retroviruses in Glioblastoma Multiforme. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 764.

- Koirala, P.; Roth, M.E.; Gill, J.; Chinai, J.M.; Ewart, M.R.; Piperdi, S.; Geller, D.S.; Hoang, B.H.; Fatakhova, Y.V.; Ghorpade, M.; et al. HHLA2, a member of the B7 family, is expressed in human osteosarcoma and is associated with metastases and worse survival. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31154.

- Xiao, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, L.-L.; Mao, L.; Wu, C.-C.; Zhang, W.-F.; Sun, Z.-J. The Expression Patterns and Associated Clinical Parameters of Human Endogenous Retrovirus-H Long Terminal Repeat-Associating Protein 2 and Transmembrane and Immunoglobulin Domain Containing 2 in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Dis. Markers 2019, 2019, 5421985.