Human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs), once external pathogens, now occupy more than 8% of the human genome and represent the merge of genomic and external factors leading to the development of cancers. Certain HERVs have perfectly assimilated into the cellular environment preventing oncogenesis, while others maintain their pathogenic potential and remain undercover until a time of cellular dysregulation. In particular, HERV genes such as gag, env, pol, np9, and rec have been discovered to carry central roles in immune regulation, checkpoint blockade, cell differentiation, cell fusion, proliferation, metastasis, and cell transformation in tumor environments. In addition, HERV long terminal repeat (LTR) regions have been shown to be involved in transcriptional regulation, creation of fusion proteins, expression of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and promotion of genome instability through recombination influencing oncogenesis.

- human endogenous retrovirus

- breast cancer

- leukemia

- lymphoma

- skin cancer

- reproductive cancer

- liver cancer

- prostate cancer

- gastrointestinal cancer

- renal cancer

- ERV

- retroelements

- LTR

1. Introduction

2. HERVs in Breast Cancer—The Rise of New Biomarkers

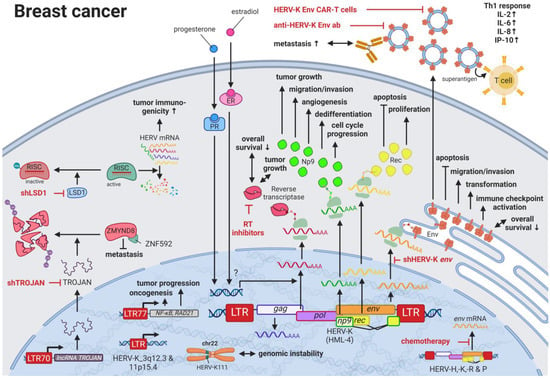

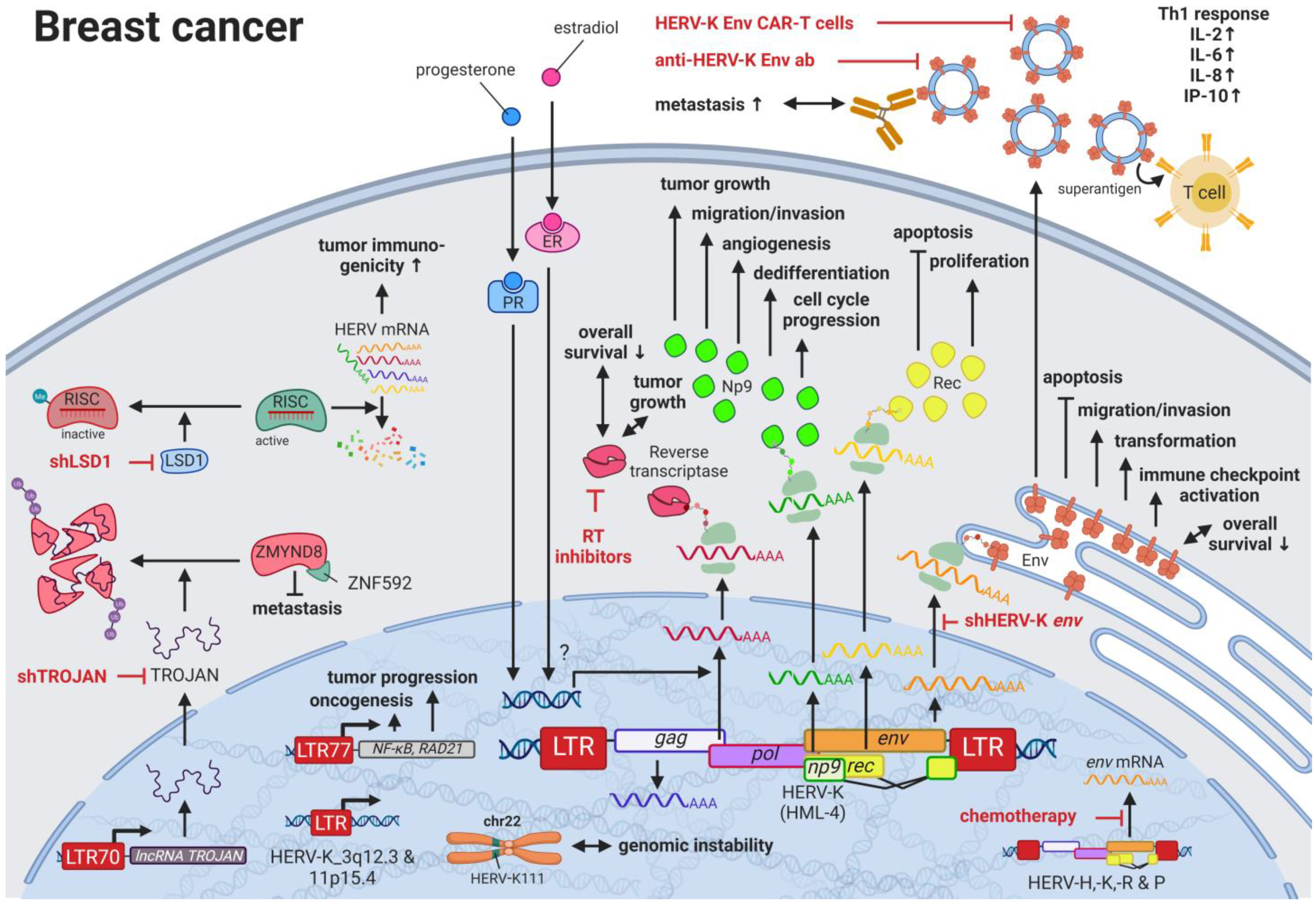

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide [28][62]. Due to the many breast cancer subtypes and their varying treatment responses [29][63], targeted treatments that evolved in recent years have become a success story. However, the field is still in need of preventive and early detection methods. HERVs might be able to close this gap providing new targets for prognostics, diagnostics, and treatments. Several groups have independently reported the overexpression of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and proteins from multiple HERV families in breast cancer cell lines and patient tissues compared to healthy tissues [30][64]. Interestingly, the menstruation-associated hormones estradiol and progesterone were observed to increase HERV-K (HML-4) env [31][65] and HERV-K (HML-4) RT transcripts as well as HERV-K (HML-4) RT protein levels [32][66] in breast cancer cell lines (Figure 1). In breast cancer patients, increased HERV-K (HML-4) RT as well as HERV-K (HML-4) Env protein levels were shown to be associated with shorter metastasis-free and overall survival [32][33][66,67]. Conversely, Montesion et al. (2018) [34][68] identified two HERV-K (HML-2) LTRs (HGCN: ERVK-5 at position 3q12.3 and ERVK3-4 at 11p15.4) that had specifically increased promoter activity in breast cancer while decreased activity in immortalized human mammary epithelial cells. Additionally, several stage-specific transcription factor (TF)-binding sites within the two LTRs were predicted to potentially contribute to promoter activity during neoplasia [34][68]. While the ERVK-5 (HERV-KII) was fixed in humans, the ERVK3-4 (HERV-K7) was found to be polymorphic in the human population with an allele frequency of 51%, presenting the prospect of a newly identified risk facto r [34][68]. In addition, breast cancer cell lines were shown to harbor HERV-K111 gene conversion/deletion events in the pericentromeric region of chromosome 22, suggesting a contribution to genomic instability [35][69].

3. HERVs in Lymphoma—The Silent Inducers

4. HERVs in Leukemia—The Lifesavers for Cancer Cells

Leukemias are the most common childhood cancers worldwide [28][60][62,121] and among the cancers with the lowest somatic mutational burden [61][122]. Both characteristics suggest genomic risk factors that can be inherited, and when accumulated, lead to carcinogenesis. Analogous to observations made for HERV LTRs in prostate cancer (see HERVs in Prostate Cancer—The Dancing Partner of the Androgen Receptor), THE-7 LTRs were discovered as drivers of a translocation of chromosome 14q32 to chromosome 7q21 in a female patient with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) [62][123]. Furthermore, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) was found to be constitutively activated through the fusion between a HERV-K3 (HML-6) sequence (HGCN: ERVK3-1) and the FGFR1 gene in a male patient with an atypical stem cell myeloproliferative disorder [63][64][124,125]. The fusion and resulting aberrant growth signal were the result of a translocation involving chromosomes 19q13.3 and chromosome 8q12 [63][64][124,125]. Furthermore, deletions of pericentromeric HERV-K111 regions in adult T-cell leukemia cell lines were enriched leading to chromosomal instabilities [35][69]. Additional to these chromosomal abnormalities as prognostic markers, Schmidt et al., (2015) identified single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers near two endogenous retroviral loci, HERV-K (HML-2) on chromosome 1 (HGCN: ERVK-7) and HERV-Fc1 on chromosome X (HGCN: ERVFC1) associated with multiple myeloma [65][126]. Both HERV regions encode nearly complete viral proteins, suggesting a functional involvement of the gene products in disease development [65][126]. Similar to the observations in lymphomas, the immune response against HERV-K (HML-2) and other HERVs appears to be rather weak or unexplored (see also HERVs in Lymphoma—The Silent Inducers) [66][100]. This might also be due to the fact that HERV-K108 (HGCN: ERVK-6) Env TM has immunosuppressive properties and has been reported to induce IL10 in PBMCs [67][127]. IL10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine, which terminates T-cell responses and leads to immune tolerance [68][128]. In a comparable way, surface CD5 expression on B cells regulates their functional fate and immunological activity. CD5 expression is tightly controlled through a HERV-E sequence located upstream of the CD5 locus (HERV-E::CD5). The HERV-E::CD5 sequence was shown to induce the integration of an alternate exon, resulting in low levels of membrane CD5 in normal B cells [69][129].5. HERVs in Skin Cancer—The Highly Addictive Treatment Targets

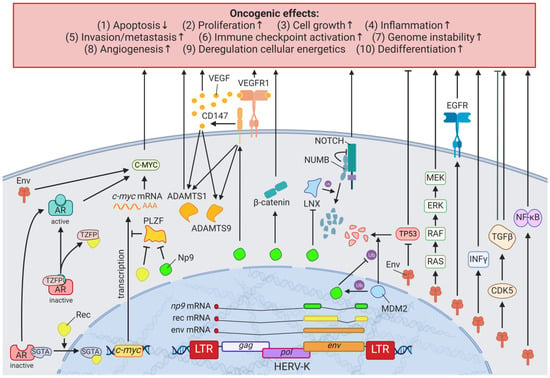

Compared to other organs, the skin is exposed to some of the highest amounts of mutagens; therefore, skin cancer is the malignancy with the highest mutational burden [61][122]. Accordingly, several physical and chemical agents with mutagenic potential have been proven to influence the regulation of HERV sequences [9][10][9,10]. As such, UV radiation, the primary risk factor for both melanomas and non-epithelial skin cancers, was shown to induce gag expression of HERV-K (HML-2) [70][143] in melanoma cell lines and tumor tissues; to reduce rec and np9 expression of HERV-K (HML-2) in primary human melanocytes and melanoma [71][144]; and to reduce pol expression of HERV-K, -H, -L, -FRD, -E, and ERV9 in melanoma cell lines [72][145], primary keratinocytes [73][146], and skin biopsies (Figure 34) [74][147].

6. HERVs in Testicular Cancer—The Governors of Tumor Suppressor Genes

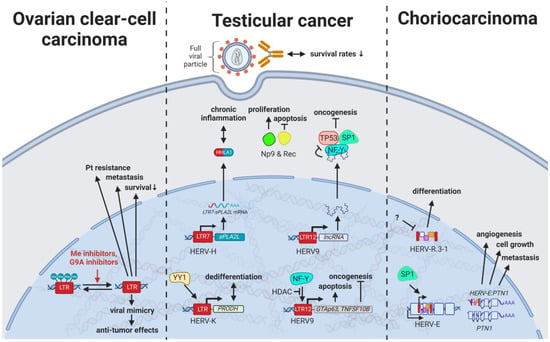

7. HERVs in Other Genital Cancers (Ovary Cancer, Choriocarcinoma, and Endometrial Cancer)—The Ascent of New Possibilities

8. HERVs in Colorectal and Gastrointestinal Cancers—The Hopes and Hazards of Family H

Colorectal cancers (CRCs) are among the most common cancers worldwide with strikingly low 5-year survival rates of less than 65–70% in Northern America, Australia/New Zealand, and many European countries [28][62]. While early diagnosis has markedly improved for older patients due to routine screenings in individuals >50 years of age, rising rates in the population under 45 years of age highlight the need for improved non-invasive prognostic and diagnostic tools [107][213]. In the last decade, research has started to focus on the influence of HERV elements on CRCs and has revealed interesting interactions, especially involving HERV-H. With over 1000 loci in the human genome, HERV-H is the most abundant HERV family carrying coding regions in the human genome [108][214]. A link between chronic inflammation and cancer has been established for various tumors, and, specifically for CRCs, an inflammatory microenvironment has been recognized to be a cause, hallmark, and consequence of disease [109][221]. A subset of patients with colon cancer was shown to express a HERV-H_9q24.1::IL33 fusion transcript required for tumor growth [110][222]. IL33 is a proinflammatory cytokine produced by epithelial and endothelial cells [111][223] that has been demonstrated to correlate in its expression with CRC progression and metastasis [112][224]. The particular function of the HERV-H_9q24.1::IL33 product is unknown but, based on the function of native IL33, might include roles as a modified cytokine or nuclear factor regulating gene transcription [111][223]. Further, HERV LTR promoted chimeric transcripts detected specifically in CRC tissues and cell lines including the ion transporter SLCO1B3λπ, which is frequently mutated in CRC [110][222]. In contrast to fusion transcripts that result in aberrant cellular genes, TIP60 (HGNC: KAT5) has been described as a regulator of the inflammatory effects of HERV expression inside the cell [113][225]. KAT5 is a tumor suppressor that is found to be repressed in early stages of CRCs and breast cancers [113][225]. A publication by Rajagopalan et al. (2018) indicated that KAT5 downregulation results in increased levels of HERV expression and associated inflammatory responses [113][225]. In normal cells, KAT5 induces H3K9 trimethylating enzymes SUV39H1 and SETDB1 in a BRD4-dependent manner, which leads to global inhibitory methylation of HERV loci [113][225]. In KAT5-repressed cancer cells, the study investigators detected induction of IRF7 mediated by the intracellular pathogen sensing STING (HGNC: TMEM173), resulting in an inflammatory response and further tumor growth [113][225]. While viral gene products are readily detected by innate immune receptors, most cellular lncRNAs escape the surveillance mechanisms and, in this fashion, are able to interfere with regulatory pathways. For instance, the lncRNA EVADR on chromosome 6q13 was observed to be induced by the ERV1 LTR MER48 specifically in colon, rectal, lung, pancreas, and stomach adenocarcinomas [114][226]. In a similar way, the ERV1 LTR MER61C on chromosome 514.1 drives transcription of the lncRNA PURPL (LINC01021), which is increased in CRC cell lines and tumors [115][116][227,228]. While higher EVADR expression was associated with slightly decreased patient survival rates [114][226], CRC tumors with higher levels of PURPL RNA resulted in improved survival rates, and induced expression in CRC cell lines lead to increased chemosensitivity according to Kaller et al. (2017) [115][227].9. HERVs in Liver Cancer—The Opening Chapter

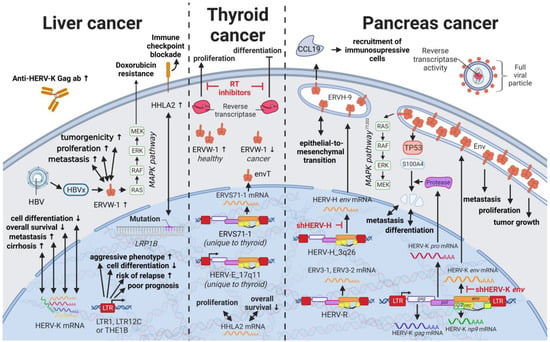

Liver cancers are the third leading cause of cancer-related death in males worldwide [117][235]; however, only limited reports are available on the influence of HERVs in liver cancer oncogenesis. Ahn and Kim (2009) together with Liang et al. (2009) reported increased expression of HERV-H, HERV-R.3-1, and HERV-P in overall liver cancers without taking into consideration distinct cancer subtypes [118][119][236,237], while several other groups reported the distinct activation of HERV-K (HML-2) and HERV-P in hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) specifically [120][121][238,239]. However, a study by Liu et al. (2021) demonstrated that the LRP1B mutation was associated with the overexpression of HERV-H LTR-Associating 2 (HHLA2) in patients with HCC [122][231]. HCC has a high morbidity and constitutes more than three-fourths of all cases with liver cancer [28][62]. Interestingly, a large number of HERV LTRs, including LTR1, LTR12C, and THE1B, were found upregulated in human HCC tumors (Figure 57) [123][240]. HCC tumors with high LTR activation were associated with high risk of relapse [123][124][240,241], a more aggressive phenotype [123][124][240,241], poor prognosis [124][241], and impaired cell differentiation in animal models [16][125][16,242]. Moreover, HERV-K (HML-2) gene products, while only moderately elevated in patients [126][243], were described to positively correlate in their expression with tumor cell dedifferentiation, mortality rates, TNM stage, and cirrhosis in HCCs [121][239]. Furthermore, in a subgroup of patients with HCC antibodies against HERV-K (HML-2) Gag were found indicating the immunogenicity of the viral gene product [120][126][238,243]. Additional to its potential as prognostic marker and therapeutic target, HERV-K (HML-2) expression might also provide resolution to a dispute concerning the origin of a liver cancer cell line. It is still debated whether HepG2 cells are derived from HCC or hepatoblastoma.

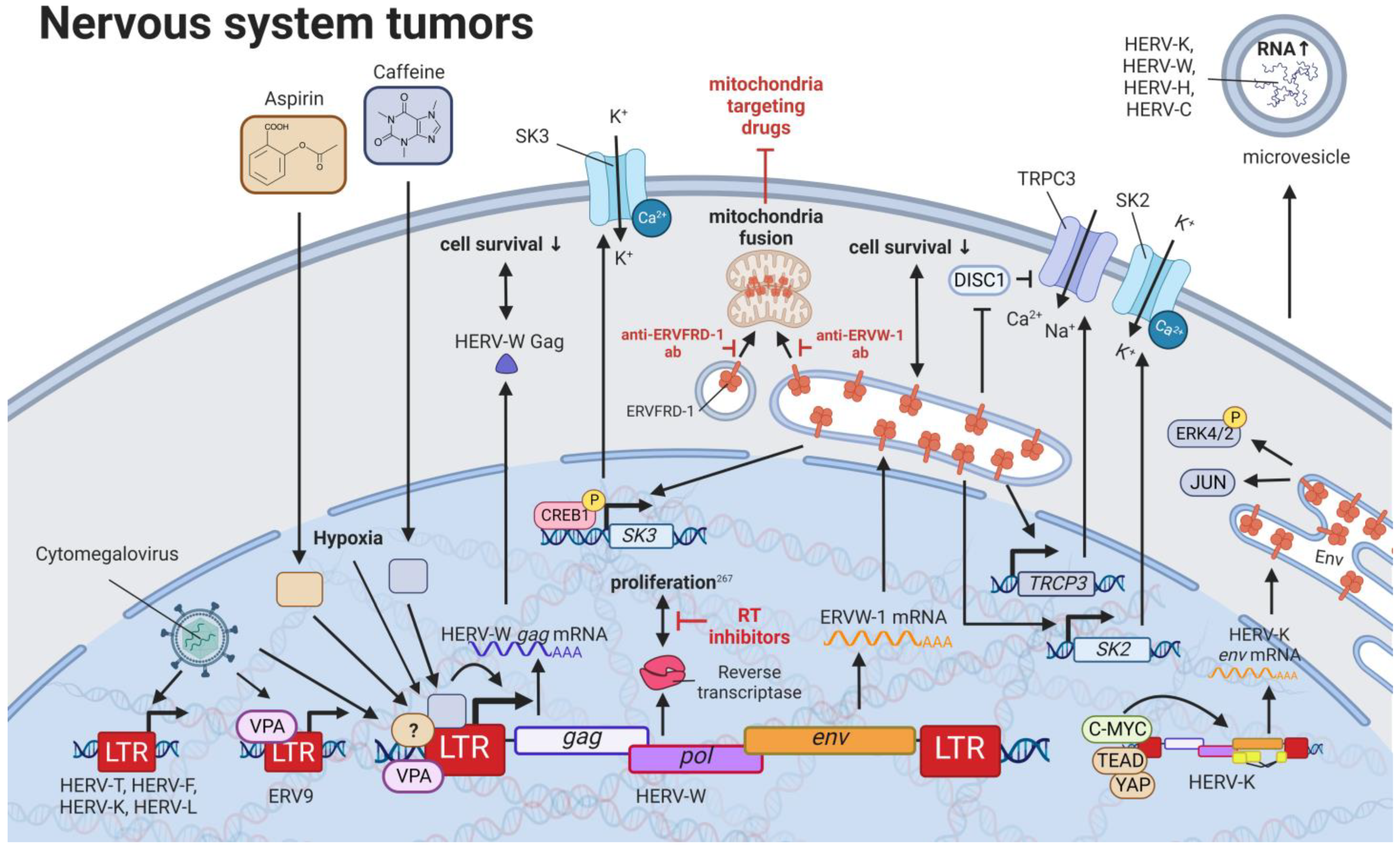

10. HERVs in Nervous System Cancers—The Wicked Side of HERV-W

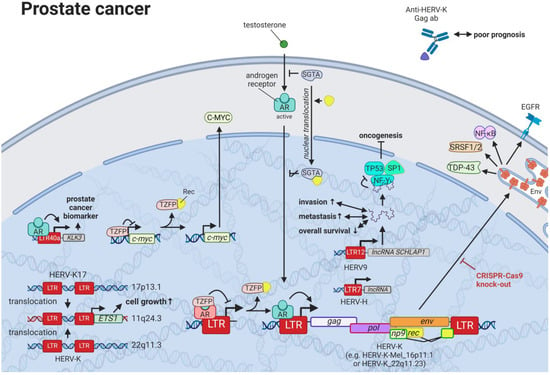

11. HERVs in Prostate Cancer—The Dancing Partner of the Androgen Receptor

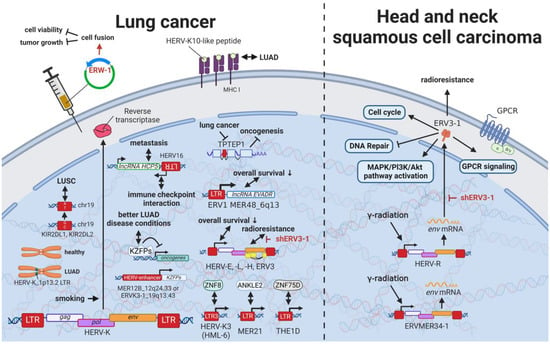

12. HERVs in Lung Cancer—The Love for Long Noncoding RNAs and Pseudogenes

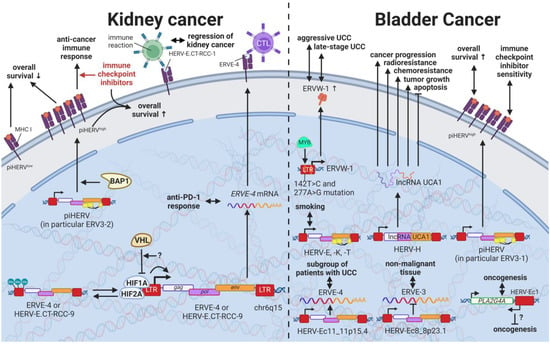

13. HERVs in Cancers of the Urinary System (Kidney and Bladder Cancer)—The Future Fire Fighters

While most HERVs operate below immune detection, research has shown that upregulation of HERVs in transformed cells can serve as a physiological tumor recognition signal, preventing the propagation of cancerous cells in early stages [146][147][148][149][117,140,203,230]. In advanced-stage cancers, such tumor suppressive functions are disrupted on multiple levels, one being through immune checkpoint activation [150][299]. Hence, newly developed immune checkpoint inhibitors have proven to be effective regimens for persistent cancers, especially for clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), where clinically significant and robust responses have been observed [151][300]. To further enhance antitumor immune responses upon immune checkpoint blockade, Panda et al. (2018) examined HERVs as prospective inducible targets in patients with ccRCC [37][71]. The study investigators determined the subset of potentially immunogenic HERVs (piHERVs) with the greatest potential to induce immune responses, such as immune infiltration, higher cytotoxic T-cell levels, and M1 macrophage abundance (Figure 911) [37][71]. Despite lower overall survival of patients with higher expression of such HERVs, piHERVhigh patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors experienced significantly improved prognosis and treatment responsiveness compared to their piHERVlow counterparts [37][71]. Out of all piHERVs, HERV-R.3-2 env (ERV3-2) expression was particularly increased in responders compared to non-responders, highlighting its tumor suppressive functions mentioned for other cancers (see HERVs in Lymphoma—The Silent Inducers and HERVs in Other Genital Cancers (Ovary Cancer, Choriocarcinoma, and Endometrial Cancer)—The Ascent of New Possibilities) [37][71]. Interestingly, similar results have been observed for patients with urothelial cancer who displayed high piHERV expression [152][301].

14. HERVs in Endocrine Cancers (Pancreas and Thyroid Cancer)—The Unknown Potential

15. HERVs in Other Cancers (Osteosarcoma, Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma)—The Hodgepodge of Hope for Novel Therapies

Rare cancers, by definition, only provide limited case numbers for investigation. Accordingly, only single reports of HERVs evaluated in such cancers are available. Despite a high incidence in children, osteosarcoma is a rare malignancy in adults [165][337]. A single study on human osteosarcoma reported the statistically significant upregulation of 35 and downregulation of 47 HERV mRNAs in osteosarcoma tissues compared to healthy controls [165][337]. The most significant HERV elements differentially expressed included LTRs of the HERV-L, HERV-K (HML-2), and ERV-1 [165][337]. Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) comprise 90% of all head and neck cancers and are relatively common [166][167][341,342]. HNSCCs are often inoperable due to the complex anatomy, making radio- and chemotherapy the only option [168][343]. Accordingly, radioresistance poses a major problem resulting in very low survival rates [28][168][62,343]. Findings by Michna et al. (2016) documenting an induction of ERV3-1 and ERVMER34-1 env upon exposure of HNSCC cell lines to γ-radiation indicate a potential target to overcome radioresistance [166][341].16. Novel Options for Cancer Treatment Facilitated by HERVs

Many studies have demonstrated increased HERV levels in tumor cell lines and tumor tissues compared to normal healthy tissues, suggesting two potential treatment approaches. On the one hand, strategies have been proposed that target pathways in which HERVs are involved [169][170][171][234,345,346], as outlined for various cancers above. HERVs might provide another pharmacological target in this way. Moreover, HERV-derived HERV restriction factors such as suppressyn (HGCN: ERVH48-1), a HERV-F-derived inhibitor of ERVW-1ε-mediated fusion, might serve as a starting point for drug development. However, discoveries of HERV genes and LTRs involved in regulatory mechanisms are very new and still advancing with the recent development of more accurate and affordable sequencing techniques.

On the other hand, treatment strategies targeting HERV proteins as tumor-specific antigens have been suggested [172][173][83,84], assuming HERV expression is a consequence of transcriptional changes in tumors. HERVs as cancer-specific antigens in hematological cancers appear to be particularly promising. Saini et al. (2020) found HERV-specific T cells are present in 17 of the 34 patients with leukemia, recognizing 29 HERV-derived peptides representing 18 different HERV loci, among which ERVH-5, ERVW-1, and ERVE-3 had the strongest responses [174][347]. Furthermore, the ancestral retroviral HEMO envelope gene (Human Endogenous MER34 ORF) is hailed as a pan-cancer target for leukemia, lung, adrenal, thyroid, breast, ovarian, uterus, cervical, prostate, esophagus, stomach, colon, liver, pancreas, renal, bladder, brain, and skin cancer [175][348]. Vaccinations of mice with HERV epitopes were shown to be safe and able to generate tumor-specific immune cells [176][177][178][179][219,339,349,350].

Furthermore, HERV-H LTR-associating proteins 1 and 2 (HHLA1 and HHLA2) on chromosomes 3q13.13 and 8q24.22 have been shown to carry immune checkpoint functions [180][353]. First described by Mager et al. in 1999, HHLA1 and HHLA2 are both members of the B7 family and obtain their polyadenylation signal through HERV-H LTR regions [181][182][354,355], thus revealing a control mechanism of viral origin [183][356]. While both proteins are part of oncogenic signaling pathways, HHLA2 has been detected in several human cancers [184][195]. HHLA2 was found to be overexpressed in basal breast cancer [185][357], triple-negative breast cancer [185][357], colorectal cancer [186][358], lung cancer [187][188][189][359,360,361], liver cancer [190][362], bladder urothelial carcinoma [191][363], ccRCC [192][193][194][364,365,366], pancreatic cancer [195][196][197][367,368,369], osteosarcoma [198][370], oral squamous cell carcinoma [199][371], and many other cancers [185][192][357,364] compared to adjacent normal tissue or healthy controls. Additionally, elevated HHLA2 protein levels were associated with tumor size, tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, and low relapse-free and overall survival in these cancers [185][186][187][188][189][190][191][192][193][194][195][196][197][198][199][357,358,359,360,361,362,363,364,365,366,367,368,369,370,371].

In summary, HERVs are involved in various homeostatic and pathogenic pathways with potential effects on cancer development and progression. The usage of HERVs themselves as therapeutic agents, as well as the HERV proteins as tumor-specific targets, are promising but must be further evaluated to exclude any undesired side effects.