You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Ruyuf Alfurayhi.

Polyacetylene phytochemicals are emerging as potentially responsible for the chemoprotective effects of consuming apiaceous vegetables. There is some evidence suggesting that polyacetylenes (PAs) impact carcinogenesis by influencing a wide variety of signalling pathways, which are important in regulating inflammation, apoptosis, cell cycle regulation, etc.

- polyacetylenes

- phytochemicals

- anti-inflammatory

- cancer prevention

- falcarinol

1. Introduction

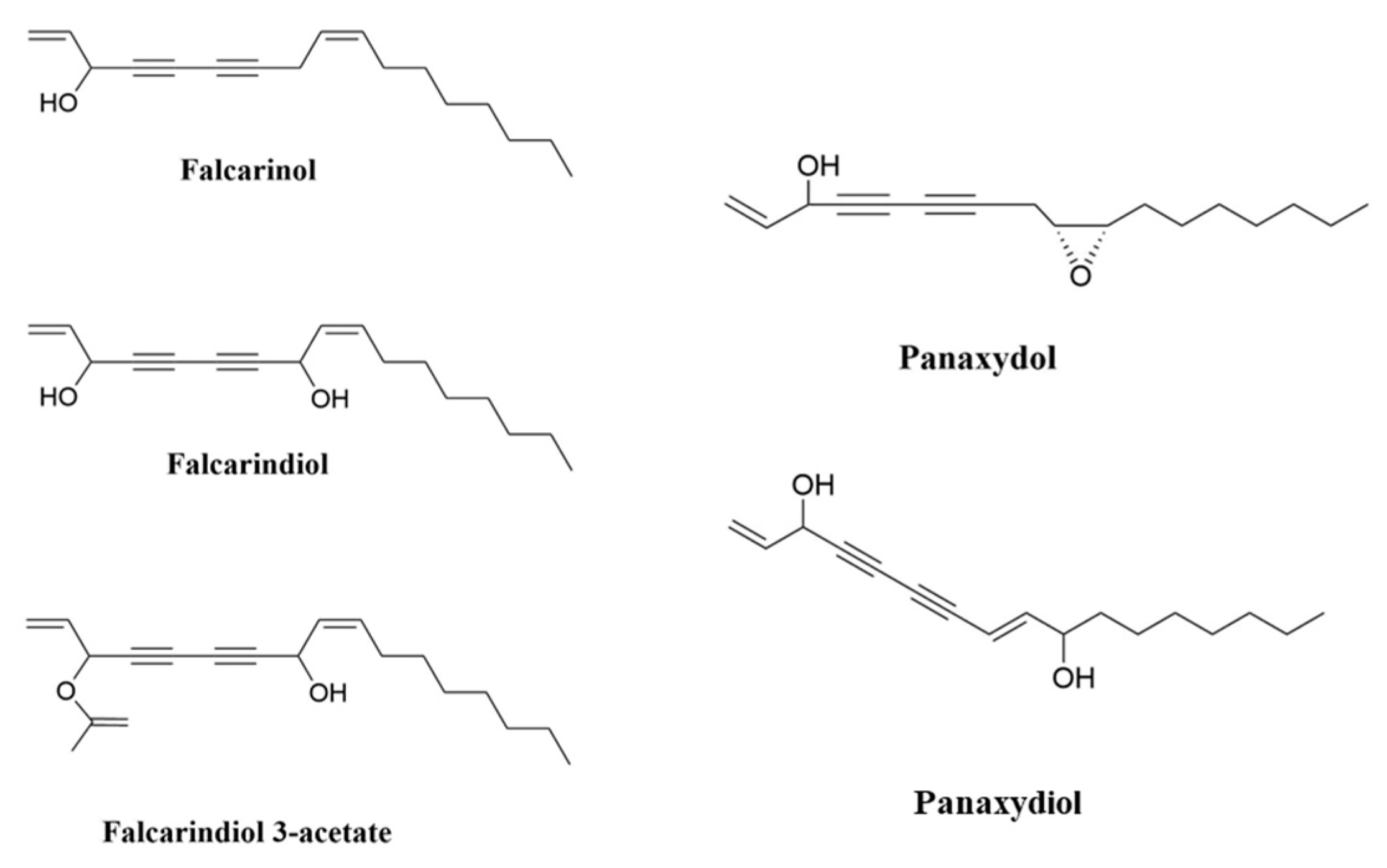

Studies have indicated the beneficial impact of eating vegetables and fruits on human health in preventing chronic diseases including cancer, which is one of the major causes of death around the world [1]. Polyacetylenes (PAs) are a class of chemicals defined by the presence of two or more carbon–carbon triple bonds in the carbonic skeleton [2]. Falcarinol-type PAs are biologically active compounds that are widely found in plants in the Apiaceae family, such as carrots, celery and parsley, and the Araliaceae family, such as ginseng. Carrot is the main dietary source of polyacetylenic oxylipins, including falcarinol (FaOH), falcarindiol (FaDOH) and falcarindiol 3-acetate (FaDOH3Ac) (Figure 1), with FaOH serving as the intermediate metabolite of PA, from which the other forms are generated [3,4,5][3][4][5]. Carrots have been studied for their nutritional value, in addition to their disease-curative effects, for almost 90 years [6]. Carrot is a rich source of the vitamin A precursor β-carotene and also provides some potentially beneficial dietary fibre. Carrot also contains other potentially bioactive phytochemicals including carotenoids, phenolics, PAs, isocoumarins, terpenes and sesquiterpenes, many of which have been extensively investigated for potential therapeutic properties against a wide range of diseases including cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, anaemia, colitis, ocular diseases and obesity [7]. Ginseng is also rich in PAs; in addition to FaOH (also called panaxynol), they include panaxydiol and panaxydol (Figure 1) [8], which have similar properties to FaOH [9,10,11][9][10][11]. Despite the extensive research on the analytical and biochemical identification and characterization of plant PAs, as well as the large number of papers on their putative biological functions, little is known about the structures and functions of the enzymes involved in PA biosynthesis [12]. Furthermore, the molecular genetic principles underlying PA production in various plant tissues are poorly understood, and little is known about the genetics and inheritance of specific PA patterns and concentrations in (crop) plants [3].

Figure 1. Chemical structures of FaOH, (3R)-falcarinol (also known as panaxynol); FaDOH, (3R,8S)-falcarindiol; FaDOH3Ac, (3R,8S)-falcarindiol-3-acetate; panaxydol; and panaxydiol.

β-carotene was initially believed to be protective against multiple chronic diseases, particularly cardiovascular disease and cancer, due to observations of associations of reduced risk of these diseases with a high dietary intake (with carrots as the primary dietary source of β-carotene) [13,14,15,16][13][14][15][16]. However, meta-analyses of subsequent intervention studies ruled out a role of β-carotene in suppressing non-communicable diseases affecting lifespan [17]. for example, dietary supplementation with purified β-carotene showed a dose-dependent increased risk of lung cancer for intakes higher than what can be obtained from food [18]. Thus, it was suggested that other bioactive substances such as PAs (FaOH and FaDOH) could be responsible for the health benefits of carrot [19]. Phytochemicals have been used as the main sources of the primary structures for conventional drugs used for curing cancer. Natural products historically have been essential in the development of new treatments for cancer and infectious diseases [20,21,22,23][20][21][22][23].

2. Polyacetylenes and Inflammation

2.1. Chronic Inflammation Disease and Cancer

Chronic inflammation is recognized as a leading promoting factor of diseases including carcinogenesis [24], which continues to be the leading cause of mortality and disability around the world [25,26,27,28][25][26][27][28]. Tumour-promoting inflammation is recognised as an enabling hallmark of cancer [29]. Cancer and inflammation are linked by intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Intrinsically, oncogenes regulate the inflammatory microenvironment, whereas extrinsically, the inflammatory microenvironment promotes the growth and spread of cancer [30]. Various cell types involved in chronic inflammation can be found in tumours, both in the surrounding stroma and within the tumour itself. Neoplasms, including some of epithelial origin, contain a significant inflammatory cell component [31]. Multiple studies on human clinical samples have revealed that inflammation influences epithelial cell turnover [32,33][32][33]. Significantly, human susceptibility to breast, liver, large bowel, bladder, prostate, gastric mucosa, ovary and skin carcinoma is increased when proliferation occurs in the context of chronic inflammation [32,33,34,35,36,37][32][33][34][35][36][37]. Chronic inflammation is linked to approximately 25% of all human cancers and increases cancer risk [38] by stimulating angiogenesis and cell proliferation, inducing gene mutations and/or inhibiting apoptosis [38]. Chronic inflammation can develop from acute inflammation if the irritant persists, although in most cases the response is chronic from the start. Chronic inflammation is characterized by the infiltration of injured tissue by mononuclear cells such as macrophages, lymphocytes and plasma cells, as well as tissue destruction and attempts at repair [31]. Helicobacter pylori infections in gastric cancer, human papillomavirus infections in cervical cancer, hepatitis B or C infections in hepatocellular carcinoma and inflammatory bowel disease in colorectal cancer (CRC) are common causes of chronic inflammation associated with cancer development [39,40][39][40]. Inflammation also causes epigenetic changes that are linked to cancer development. Natural PAs from diverse food and medicinal plants and their derivatives exert multiple bioactivities, including anti-inflammatory properties [41]. PAs can impact inflammation through known and unknown pathways. Evidence supports that PA compounds improve human health by stimulating anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory mechanisms [3]. These PAs contain triple bonds that functionality convert them into highly alkylating compounds that are reactive to proteins and other biomolecules. This unique molecular structure might be the key to understanding the beneficial effects of PAs such as their anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective function [41]. Recent research has suggested that the anti-cancer role of certain foods might be attributed to their anti-inflammatory function. Root vegetables, and particularly carrots, are promising natural sources in this respect thanks to their rich content of PAs [3,41,42,43][3][41][42][43]. The anti-inflammatory properties of purple carrots have been suggested to be due to the high levels of anthocyanin pigments [44]; however, another study showed that PAs, not anthocyanins, are responsible for the anti-inflammatory bioactivity of purple carrots [45]. In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that the health-benefitting effects of carrots and other root vegetables might be attributed to PAs, such as FaOH and FaDOH [46]. Other dietary compounds, including several different phytochemicals, have been examined in the context of cancer chemoprevention; however, until now the measured effects [47,48,49,50][47][48][49][50] have been quite small and inconsistent compared with those found for PAs.2.2. Inhibition of Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB) Pathways

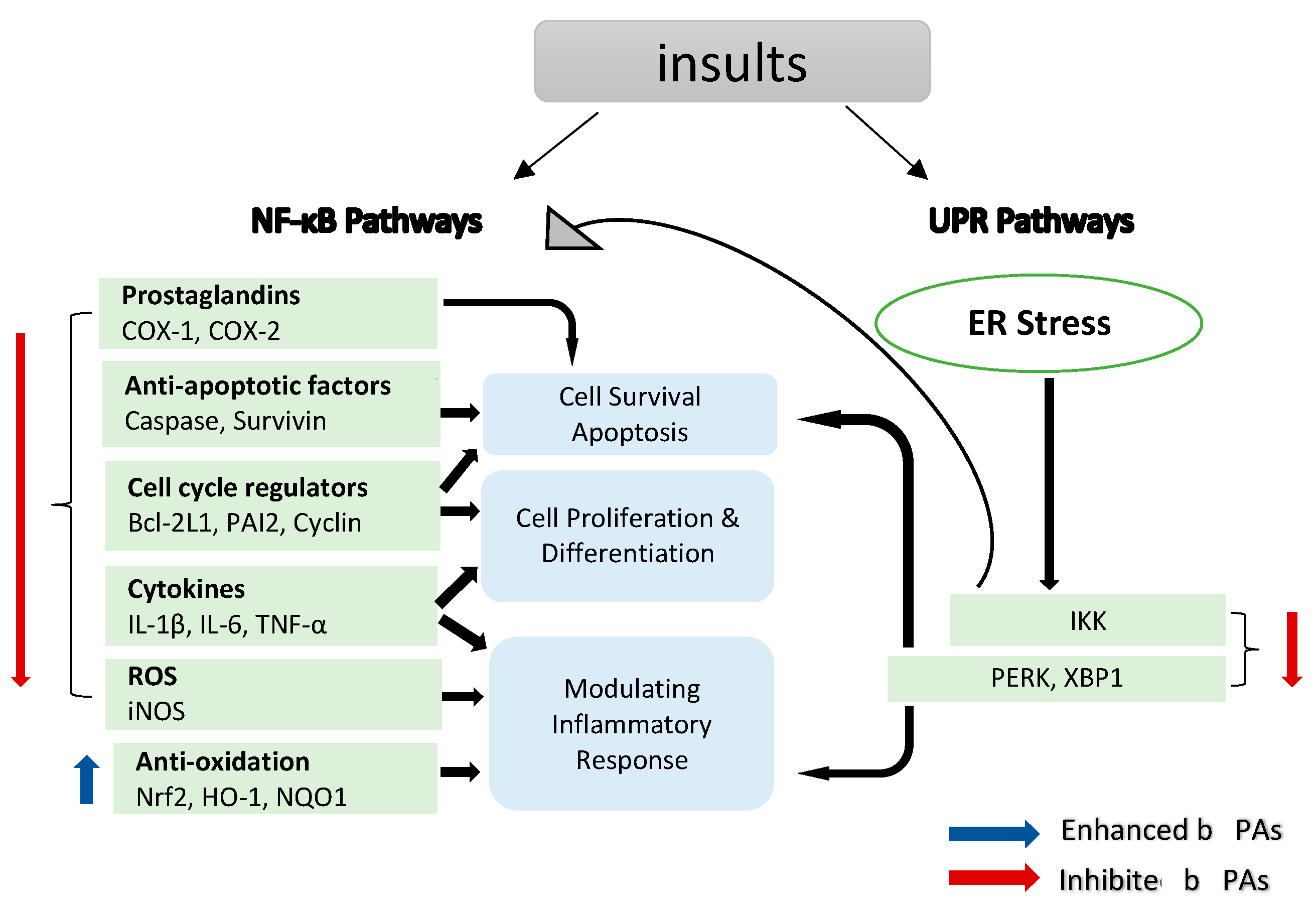

NF-κB is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of many genes involved in the regulation of inflammation and autoimmune diseases [51,52][51][52]. Moreover, NF-κB plays a significant role in inflammation-induced cancers, as NF-κB is one of the major inflammatory pathways that are triggered by, for example, infections causing chronic inflammation [39,40,53][39][40][53]. Cellular immunity, inflammation and stress are all regulated by NF-κB signalling, as are cell differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis (Figure 2) [54,55][54][55]. Both solid and hematologic malignancies frequently modify the NF-κB pathway in ways that promote tumour cell proliferation and survival [56,57,58][56][57][58].

Figure 2. NF-κB target genes implicated in the onset and progression of inflammation. NF-κB is a transcription factor that is inducible. After activation, it can regulate inflammation by activating the transcription of several genes. NF-κB regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation in addition to promoting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress results in an inflammatory unfolded protein response (UPR). Stress on the ER induces apoptosis by activating inflammation. This can be accomplished by stimulating IKK complex (element of the NF-κB) or (X-box binding protein 1) XBP1 and (protein kinase R-like ER kinase) PERK through a mediator. These trigger the release of pro-inflammatory molecules, hence accelerating cell death.

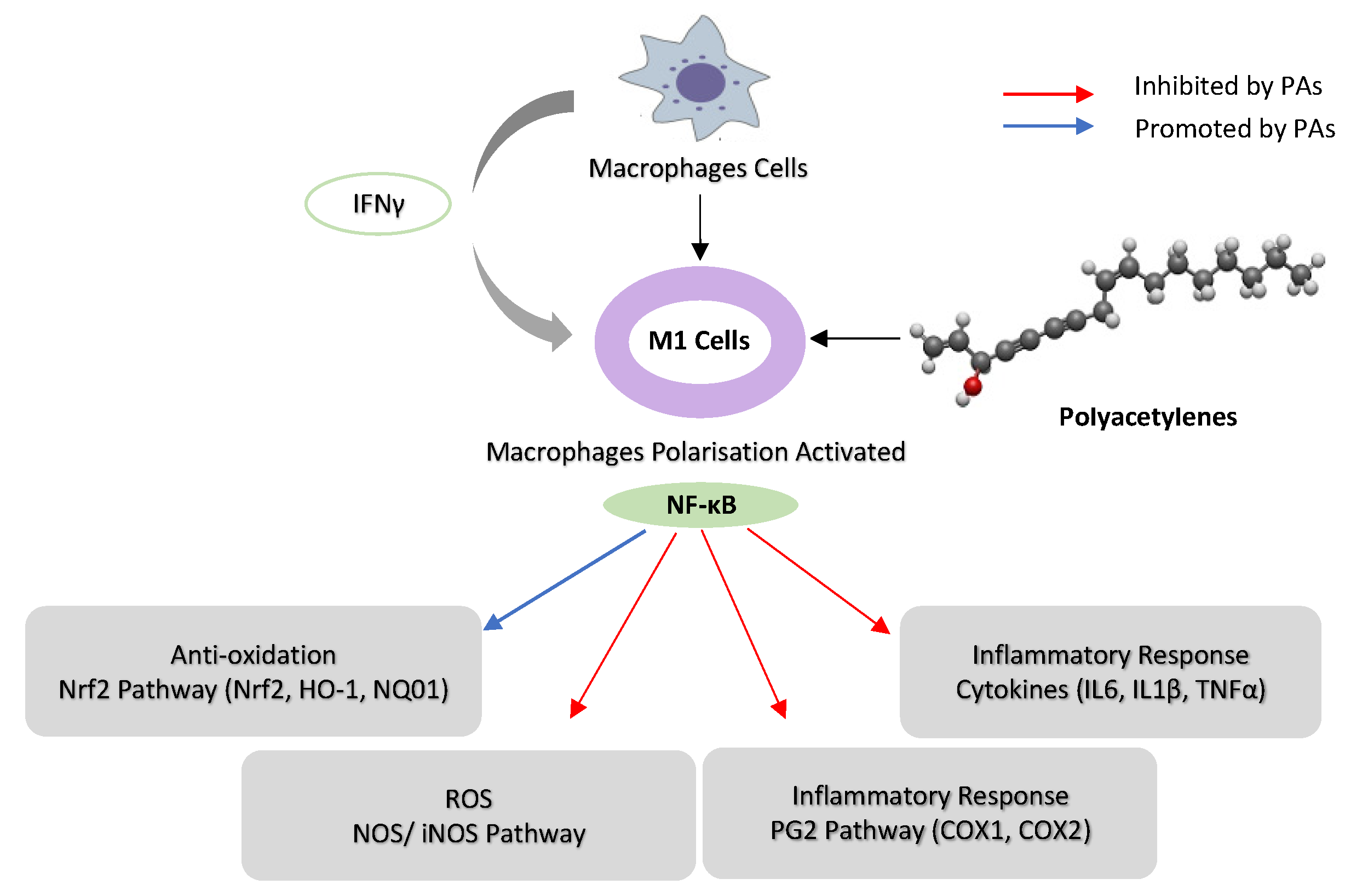

Figure 3. Schematic representation of the possible mechanism of immunoregulation activity of poly-acetylenes (PAs) in macrophages. (Interferon-γ) IFN-γ activates macrophage cells to M1, and PAs downregulate NF-κB activities in M1 macrophages by inhibiting iNOS, COX-1 and COX-2. PAs suppress the inflammatory response by inhibiting cytokines (IL-16, IL-1β and TNF-α) and upregulating Nrf2 pathway (HO-1 and NQO1) in macrophages.

2.3. Oxidative Stress

2.3.1. Inhibition of Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS) and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Pathways

Nitric oxide (NO) is essential in a number of physiological functions, such as host defence, where it prevents the spread of disease-causing microbes within cells by stifling their reproduction [80]. The upregulation of NO expression in response to cytokines or pathogen-derived chemicals is a crucial part of the host’s defence against different types of intracellular pathogens. Different cell types produce the enzyme NOS, which catalyses the synthesis of NO, at high levels in a number of different tumour types [81]. Inflammation induces a specific form of NOS, i.e., the inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), via activating iNOS gene transcription (Figure 2) [82]. iNOS is involved in complex immunomodulatory and antitumor mechanisms, which have a role in eliminating bacteria, viruses and parasites [83]. A considerable number of studies have been published on the role of PAs in iNOS expression in inflammation. Studies have demonstrated that FaOH extracted from P. quinquefolius inhibited iNOS expression in ANA-1 mΦ macrophage cells that were polarized to M1 [8] and LPS-induced iNOS expression in macrophages [84[84][85],85], leading to colitis suppression [8]. Moreover, FaDOH was tested on rat primary astrocytes for its impact on LPS/IFN-γ-induced iNOS expression. FaDOH blocked 80% of LPS/IFN-γ-induced iNOS by reducing iNOS protein and mRNA in a dose-dependent manner. FaDOH was shown to suppress iNOS expression, and it inhibited IKK, JAK, NF-κB and Stat1 (Figure 2 and Figure 3) [64]. Another study showed a dose-dependent reduction in nitric oxide production in macrophage cells, where treatment with an extract of purple carrots containing PAs significantly reduced iNOS activity and iNOS expression in macrophage cells [45]. PAs reduced nitric oxide production in macrophage cells without cytotoxicity [45]. In vivo, purple carrots also inhibited inflammation in colitic mice and reduced colonic mRNA expression of iNOS [44]. FaOH from H. moellendorffii roots inhibits the LPS-induced overexpression of iNOS in RAW264.7 cells [65]. FaOH and other PAs from P. quinquefolius such as panaxydiol have a suppressive effect on iNOS expression in macrophages treated with LPS [85].2.3.2. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Pathways

Oxidative stress is described as an imbalance between the generation of free radicals and reactive metabolites, also known as oxidants or reactive oxygen species (ROS), and their removal by protective mechanisms, also known as antioxidants. Electron transfer is involved in oxidative and antioxidative processes, which influence the redox state of cells and the organism. The altered redox state stimulates or inhibits the activities of various signal proteins, which have an effect on cell fate [86,87][86][87]. PAs promote apoptosis preferentially in cancer cells mediated ROS stress. A study has analysed ROS production in MCF-7 cells after treating with panaxydol. The increase in the ROS levels started at 10–20 min after the panaxydol treatment. The role of NADPH oxidase was investigated in order to determine the source of ROS after panaxydol treatment. The creation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by NADPH oxidase appeared to take precedence, while ROS production in the mitochondria was secondary but also necessary, suggesting that NADPH oxidase generates ROS in the presence of panaxydol. Panaxydol was tested on different cell lines to investigate whether the induction of apoptosis occurred preferentially in cancer cells. In this study, panaxydol induced apoptosis only in cancer cells [88]. FaOH and FaDOH from carrot were tested for their effects on the oxidative stress responses of primary myotube cultures. The effects of 100 μM of H2O2 on the intracellular formation of ROS, the transcription of the antioxidative enzyme, cytosolic glutathione peroxidase (cGPx), and the heat shock proteins (HSP) HSP70 and heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) were studied after 24 h treatment with FaOH and FaDOH at a wide range of concentrations. At intermediate concentrations, under which only moderate cytotoxicity was shown, intracellular ROS formation was slightly enhanced by PAs. In addition, PAs increased the transcription of cGPx and decreased the transcription of HSP70 and HO-1. The enhanced cGPx transcription may have decreased the need for the protective properties of HSPs as an adaptive response to the elevated ROS production. However, ROS production was significantly reduced with higher doses of PAs (causing substantial cytoxicity), and the transcription of HSP70 and HO-1 decreased to a lesser extent, while the induction of cGPx was marginally reduced, showing a necessity for the protective and repairing functions of HSPs [89]. Transcription factor Nrf2 (also known as nuclear factor erythroid 2-like 2) regulates the expression of various antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective factors, including heme oxygenase-1 (Hmox1, HO-1) and NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase-1 (NQO1). S-alkylation of the protein Keap1, which normally inhibits Nrf2, is induced by FaDOH extracted from Notopterygium incisum (N. incisum), as reported in [90]. Moreover, nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 and expression of HO-1 were both enhanced in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells by FaOH from H. moellendorffii roots [65]. FaOH also inhibited the inflammatory factor level and reduced nitric oxide production in BV-2 microglia. FaOH also reduced the levels of LPS-induced oxidative stress in BV-2 microglia [61]. In addition, FaOH inhibited inflammation in macrophages by activating Nrf2 [85]. HO-1 is linked to redox-regulated gene expression. Chemical and physical stimuli that produce ROS either directly or indirectly cause the expression of HO-1 to respond [91]. A one-week study looked at the effects of FaOH (5 mg/kg twice per day in CB57BL/6 mice) pre-treatment on acute intestinal and systemic inflammation. FaOH effectively increased HO-1 mRNA and protein levels in both the mouse liver and intestine and reduced the levels of the plasma chemokine eotaxin and the myeloid inflammatory cell growth factor GM-CSF, both of which are involved in the recruitment and maintenance of first-responder immune cells [92].References

- Wang, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, G.; Bao, W.; Hu, F.B. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Postgrad. Med. J. 2014, 349, g4490.

- Negri, R. Polyacetylenes from terrestrial plants and fungi: Recent phytochemical and biological advances. Fitoterapia 2015, 106, 92–109.

- Dawid, C.; Dunemann, F.; Schwab, W.; Nothnagel, T.; Hofmann, T. Bioactive C17-polyacetylenes in carrots (Daucus carota L.): Current knowledge and future perspectives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 9211–9222.

- Hansen, L.; Boll, P.M. Polyacetylenes in Araliaceae: Their chemistry, biosynthesis and biological significance. Phytochemistry 1986, 25, 285–293.

- Stefanson, A.; Bakovic, M. Dietary polyacetylene falcarinol upregulated intestinal heme oxygenase-1 and modified plasma cytokine profile in late phase lipopolysaccharide-induced acute inflammation in CB57BL/6 mice. Nutr. Res. 2020, 80, 89–105.

- Moore, T. Vitamin A and carotene: The association of vitamin A activity with carotene in the carrot root. Biochem. J. 1929, 23, 803.

- Butnariu, M. Therapeutic Properties of Vegetable. J. Bioequivalence Bioavailab. 2014, 6, e55.

- Chaparala, A.; Poudyal, D.; Tashkandi, H.; Witalison, E.E.; Chumanevich, A.A.; Hofseth, J.L.; Nguyen, I.; Hardy, O.; Pittman, D.L.; Wyatt, M.D. Panaxynol, a bioactive component of American ginseng, targets macrophages and suppresses colitis in mice. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 2026.

- Cambria, C.; Sabir, S.; Shorter, I.C. Ginseng; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2019.

- Hong, H.; Baatar, D.; Hwang, S.G. Anticancer activities of ginsenosides, the main active components of ginseng. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 8858006.

- Yang, S.; Li, F.; Lu, S.; Ren, L.; Bian, S.; Liu, M.; Zhao, D.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. Ginseng root extract attenuates inflammation by inhibiting the MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway and activating autophagy and p62-Nrf2-Keap1 signaling in vitro and in vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 283, 114739.

- Jeon, J.E.; Kim, J.-G.; Fischer, C.R.; Mehta, N.; Dufour-Schroif, C.; Wemmer, K.; Mudgett, M.B.; Sattely, E. A pathogen-responsive gene cluster for highly modified fatty acids in tomato. Cell 2020, 180, 176–187.e119.

- Mares-Perlman, J.A.; Millen, A.E.; Ficek, T.L.; Hankinson, S.E. The body of evidence to support a protective role for lutein and zeaxanthin in delaying chronic disease. Overview. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 518S–524S.

- Sommer, A.; Vyas, K.S. A global clinical view on vitamin A and carotenoids. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 1204S–1206S.

- Tapiero, H.; Townsend, D.M.; Tew, K.D. The role of carotenoids in the prevention of human pathologies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2004, 58, 100–110.

- Deding, U.; Baatrup, G.; Christensen, L.P.; Kobaek-Larsen, M. Carrot intake and risk of colorectal cancer: A prospective cohort study of 57,053 Danes. Nutrients 2020, 12, 332.

- Bjelakovic, G.; Nikolova, D.; Gluud, C. Antioxidant Supplements to Prevent Mortality. JAMA-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013, 310, 1178–1179.

- Kordiak, J.; Bielec, F.; Jabłoński, S.; Pastuszak-Lewandoska, D. Role of Beta-Carotene in Lung Cancer Primary Chemoprevention: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1361.

- Brandt, K.; Christensen, L.P.; Hansen-Møller, J.; Hansen, S.; Haraldsdottir, J.; Jespersen, L.; Purup, S.; Kharazmi, A.; Barkholt, V.; Frøkiær, H. Health promoting compounds in vegetables and fruits: A systematic approach for identifying plant components with impact on human health. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 15, 384–393.

- Atanasov, A.G.; Waltenberger, B.; Pferschy-Wenzig, E.-M.; Linder, T.; Wawrosch, C.; Uhrin, P.; Temml, V.; Wang, L.; Schwaiger, S.; Heiss, E.H. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1582–1614.

- Harvey, A.L.; Edrada-Ebel, R.; Quinn, R.J. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 111–129.

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Supuran, C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216.

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803.

- Singh, N.; Baby, D.; Rajguru, J.P.; Patil, P.B.; Thakkannavar, S.S.; Pujari, V.B. Inflammation and cancer. Ann. Afr. Med. 2019, 18, 121.

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1822–1832.

- Ju, T.; Hernandez, L.; Mohsin, N.; Labib, A.; Frech, F.; Nouri, K. Evaluation of risk in chronic cutaneous inflammatory conditions for malignant transformation. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 231–242.

- Park, J.M.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Bae, S.U.; Lee, H.W. Inflammatory bowel disease–associated intestinal fibrosis. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2023, 57, 60–66.

- Lirhus, S.S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Health Registry Data: Estimates of Incidence, Prevalence and Regional Treatment Variation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, January 2022.

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, 31–46.

- Raposo, T.; Beirão, B.; Pang, L.; Queiroga, F.; Argyle, D. Inflammation and cancer: Till death tears them apart. Vet. J. 2015, 205, 161–174.

- Macarthur, M.; Hold, G.L.; El-Omar, E.M. Inflammation and Cancer II. Role of chronic inflammation and cytokine gene polymorphisms in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal malignancy. Am. J. Physiol. -Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2004, 286, G515–G520.

- De Marzo, A.M.; Marchi, V.L.; Epstein, J.I.; Nelson, W.G. Proliferative inflammatory atrophy of the prostate: Implications for prostatic carcinogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 155, 1985–1992.

- Kuper, H.; Adami, H.O.; Trichopoulos, D. Infections as a major preventable cause of human cancer. J. Intern. Med. 2001, 249, 61–74.

- Scholl, S.; Pallud, C.; Beuvon, F.; Hacene, K.; Stanley, E.; Rohrschneider, L.; Tang, R.; Pouillart, P.; Lidereau, R. Anti-colony-stimulating factor-1 antibody staining in primary breast adenocarcinomas correlates with marked inflammatory cell infiltrates and prognosis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1994, 86, 120–126.

- Ernst, P.B.; Gold, B.D. The disease spectrum of Helicobacter pylori: The immunopathogenesis of gastroduodenal ulcer and gastric cancer. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000, 54, 615.

- Ness, R.B.; Cottreau, C. Possible role of ovarian epithelial inflammation in ovarian cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999, 91, 1459–1467.

- Bröcker, E.; Zwadlo, G.; Holzmann, B.; Macher, E.; Sorg, C. Inflammatory cell infiltrates in human melanoma at different stages of tumor progression. Int. J. Cancer 1988, 41, 562–567.

- Kundu, J.K.; Surh, Y.-J. Inflammation: Gearing the journey to cancer. Mutat. Res./Rev. Mutat. Res. 2008, 659, 15–30.

- Coussens, L.M.; Werb, Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867.

- Multhoff, G.; Molls, M.; Radons, J. Chronic inflammation in cancer development. Front. Immunol. 2012, 2, 98.

- Christensen, L.P. Bioactive C17 and C18 acetylenic oxylipins from terrestrial plants as potential lead compounds for anticancer drug development. Molecules 2020, 25, 2568.

- Xie, Q.; Wang, C. Polyacetylenes in herbal medicine: A comprehensive review of its occurrence, pharmacology, toxicology, and pharmacokinetics (2014–2021). Phytochemistry 2022, 113288.

- Ahmad, T.; Cawood, M.; Iqbal, Q.; Ariño, A.; Batool, A.; Tariq, R.M.S.; Azam, M.; Akhtar, S. Phytochemicals in Daucus carota and their health benefits. Foods 2019, 8, 424.

- Kim, Y.-J.; Ju, J.; Song, J.-L.; Yang, S.-g.; Park, K.-Y. Anti-colitic effect of purple carrot on dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in C57BL/6J Mice. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2018, 23, 77.

- Metzger, B.T.; Barnes, D.M.; Reed, J.D. Purple carrot (Daucus carota L.) polyacetylenes decrease lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of inflammatory proteins in macrophage and endothelial cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3554–3560.

- Kobaek-Larsen, M.; Baatrup, G.; Notabi, M.K.; El-Houri, R.B.; Pipó-Ollé, E.; Christensen Arnspang, E.; Christensen, L.P. Dietary polyacetylenic oxylipins falcarinol and falcarindiol prevent inflammation and colorectal neoplastic transformation: A mechanistic and dose-response study in a rat model. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2223.

- George, B.P.; Chandran, R.; Abrahamse, H. Role of phytochemicals in cancer chemoprevention: Insights. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1455.

- Islam, S.U.; Ahmed, M.B.; Ahsan, H.; Islam, M.; Shehzad, A.; Sonn, J.K.; Lee, Y.S. An update on the role of dietary phytochemicals in human skin cancer: New insights into molecular mechanisms. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 916.

- Rahman, M.A.; Rahman, M.H.; Hossain, M.S.; Biswas, P.; Islam, R.; Uddin, M.J.; Rahman, M.H.; Rhim, H. Molecular insights into the multifunctional role of natural compounds: Autophagy modulation and cancer prevention. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 517.

- Kumar, S.; Gupta, S. Dietary phytochemicals and their role in cancer chemoprevention. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2021, 7, 51.

- Spooner, R.; Yilmaz, Ö. The role of reactive-oxygen-species in microbial persistence and inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 334–352.

- Kauppinen, A.; Suuronen, T.; Ojala, J.; Kaarniranta, K.; Salminen, A. Antagonistic crosstalk between NF-κB and SIRT1 in the regulation of inflammation and metabolic disorders. Cell. Signal. 2013, 25, 1939–1948.

- Crusz, S.M.; Balkwill, F.R. Inflammation and cancer: Advances and new agents. Nat. Rev. Clin. Ocol. 2015, 12, 584–596.

- Song, W.; Mazzieri, R.; Yang, T.; Gobe, G.C. Translational significance for tumor metastasis of tumor-associated macrophages and epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1106.

- Kwon, H.-J.; Choi, G.-E.; Ryu, S.; Kwon, S.J.; Kim, S.C.; Booth, C.; Nichols, K.E.; Kim, H.S. Stepwise phosphorylation of p65 promotes NF-κB activation and NK cell responses during target cell recognition. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11686.

- Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. Shared principles in NF-κB signaling. Cell 2008, 132, 344–362.

- Sau, A.; Lau, R.; Cabrita, M.A.; Nolan, E.; Crooks, P.A.; Visvader, J.E.; Pratt, M.C. Persistent activation of NF-κB in BRCA1-deficient mammary progenitors drives aberrant proliferation and accumulation of DNA damage. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 19, 52–65.

- Salazar, L.; Kashiwada, T.; Krejci, P.; Meyer, A.N.; Casale, M.; Hallowell, M.; Wilcox, W.R.; Donoghue, D.J.; Thompson, L.M. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 interacts with and activates TGFβ-activated kinase 1 tyrosine phosphorylation and NFκB signaling in multiple myeloma and bladder cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86470.

- Burstein, E.; Fearon, E.R. Colitis and cancer: A tale of inflammatory cells and their cytokines. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 464–467.

- Sun, S.-C. The non-canonical NF-κB pathway in immunity and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 545–558.

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, S.; Cai, E.; Zhu, H. Study on the antidepressant effect of panaxynol through the IκB-α/NF-κB signaling pathway to inhibit the excessive activation of BV-2 microglia. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111387.

- Chen, T.; Mou, Y.; Tan, J.; Wei, L.; Qiao, Y.; Wei, T.; Xiang, P.; Peng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z. The protective effect of CDDO-Me on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 25, 55–64.

- Kang, H.; Bang, T.-S.; Lee, J.-W.; Lew, J.-H.; Eom, S.H.; Lee, K.; Choi, H.-Y. Protective effect of the methanol extract from Cryptotaenia japonica Hassk. against lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 199.

- Shiao, Y.-J.; Lin, Y.-L.; Sun, Y.-H.; Chi, C.-W.; Chen, C.-F.; Wang, C.-N. Falcarindiol impairs the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase by abrogating the activation of IKK and JAK in rat primary astrocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 144, 42.

- Kim, H.N.; Kim, J.D.; Yeo, J.H.; Son, H.-J.; Park, S.B.; Park, G.H.; Eo, H.J.; Jeong, J.B. Heracleum moellendorffii roots inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory mediators through the inhibition of NF-κB and MAPK signaling, and activation of ROS/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 310.

- Yao, C.; Narumiya, S. Prostaglandin-cytokine crosstalk in chronic inflammation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 337–354.

- Lee, S.; Shin, S.; Kim, H.; Han, S.; Kim, K.; Kwon, J.; Kwak, J.-H.; Lee, C.-K.; Ha, N.-J.; Yim, D. Anti-inflammatory function of arctiin by inhibiting COX-2 expression via NF-κB pathways. J. Inflamm. 2011, 8, 16.

- Nagaraju, G.P.; El-Rayes, B.F. Cyclooxygenase-2 in gastrointestinal malignancies. Cancer 2019, 125, 1221–1227.

- Ghosh, N.; Chaki, R.; Mandal, V.; Mandal, S.C. COX-2 as a target for cancer chemotherapy. Pharmacol. Rep. 2010, 62, 233–244.

- Agrawal, U.; Kumari, N.; Vasudeva, P.; Mohanty, N.K.; Saxena, S. Overexpression of COX2 indicates poor survival in urothelial bladder cancer. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2018, 34, 50–55.

- Harris, R.E.; Casto, B.C.; Harris, Z.M. Cyclooxygenase-2 and the inflammogenesis of breast cancer. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 5, 677.

- Petkova, D.; Clelland, C.; Ronan, J.; Pang, L.; Coulson, J.; Lewis, S.; Knox, A. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 in non-small cell lung cancer. Respir. Med. 2004, 98, 164–172.

- Yip-Schneider, M.T.; Barnard, D.S.; Billings, S.D.; Cheng, L.; Heilman, D.K.; Lin, A.; Marshall, S.J.; Crowell, P.L.; Marshall, M.S.; Sweeney, C.J. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 139–146.

- Saba, N.F.; Choi, M.; Muller, S.; Shin, H.J.C.; Tighiouart, M.; Papadimitrakopoulou, V.A.; El-Naggar, A.K.; Khuri, F.R.; Chen, Z.G.; Shin, D.M. Role of Cyclooxygenase-2 in Tumor Progression and Survival of Head and Neck Squamous Cell CarcinomaRole of COX-2 in Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 2009, 2, 823–829.

- Masferrer, J.L.; Leahy, K.M.; Koki, A.T.; Zweifel, B.S.; Settle, S.L.; Woerner, B.M.; Edwards, D.A.; Flickinger, A.G.; Moore, R.J.; Seibert, K. Antiangiogenic and Antitumor Activities of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 1306–1311.

- Shi, G.; Li, D.; Fu, J.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Qu, R.; Jin, X.; Li, D. Upregulation of cyclooxygenase-2 is associated with activation of the alternative nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathway in colonic adenocarcinoma. Am J Transl Res 2015, 7, 1612–1620.

- Qualls, J.E.; Kaplan, A.M.; Van Rooijen, N.; Cohen, D.A. Suppression of experimental colitis by intestinal mononuclear phagocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 80, 802–815.

- Xavier, R.J.; Podolsky, D.K. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2007, 448, 427–434.

- Chen, S. Natural products triggering biological targets-a review of the anti-inflammatory phytochemicals targeting the arachidonic acid pathway in allergy asthma and rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Drug Targets 2011, 12, 288–301.

- Bogdan, C.; Röllinghoff, M.; Diefenbach, A. The role of nitric oxide in innate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2000, 173, 17–26.

- Ekmekcioglu, S.; Grimm, E.A.; Roszik, J. Targeting iNOS to increase efficacy of immunotherapies. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2017, 13, 1105–1108.

- Hausel, P.; Latado, H.; Courjault-Gautier, F.; Felley-Bosco, E. Src-mediated phosphorylation regulates subcellular distribution and activity of human inducible nitric oxide synthase. Oncogene 2006, 25, 198–206.

- Pautz, A.; Art, J.; Hahn, S.; Nowag, S.; Voss, C.; Kleinert, H. Regulation of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nitric Oxide 2010, 23, 75–93.

- Ichikawa, T.; Li, J.; Nagarkatti, P.; Nagarkatti, M.; Hofseth, L.J.; Windust, A.; Cui, T. American ginseng preferentially suppresses STAT/iNOS signaling in activated macrophages. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 125, 145–150.

- Qu, C.; Li, B.; Lai, Y.; Li, H.; Windust, A.; Hofseth, L.J.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P.; Wang, X.L.; Tang, D. Identifying panaxynol, a natural activator of nuclear factor erythroid-2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) from American ginseng as a suppressor of inflamed macrophage-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 168, 326–336.

- Ďuračková, Z. Some current insights into oxidative stress. Physiol. Res. 2010, 59, 459–469.

- Scialo, F.; Sanz, A. Coenzyme Q redox signalling and longevity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 164, 187–205.

- Kim, J.Y.; Yu, S.-J.; Oh, H.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, Y.; Sohn, J. Panaxydol induces apoptosis through an increased intracellular calcium level, activation of JNK and p38 MAPK and NADPH oxidase-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species. Apoptosis 2011, 16, 347–358.

- Young, J.F.; Christensen, L.P.; Theil, P.K.; Oksbjerg, N. The polyacetylenes falcarinol and falcarindiol affect stress responses in myotube cultures in a biphasic manner. Dose-Response 2008, 6, 239–251.

- Ohnuma, T.; Nakayama, S.; Anan, E.; Nishiyama, T.; Ogura, K.; Hiratsuka, A. Activation of the Nrf2/ARE pathway via S-alkylation of cysteine 151 in the chemopreventive agent-sensor Keap1 protein by falcarindiol, a conjugated diacetylene compound. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010, 244, 27–36.

- Chiang, S.K.; Chen, S.E.; Chang, L.C. A Dual Role of Heme Oxygenase-1 in Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 20, 39.

- Stefanson, A.L.; Bakovic, M. Falcarinol is a potent inducer of heme oxygenase-1 and was more effective than sulforaphane in attenuating intestinal inflammation at diet-achievable doses. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 3153527.

More