The new era of nanomedicine offers significant opportunities for cancer diagnostics and treatment. Magnetic nanoplatforms could be highly effective tools for cancer diagnosis and treatment in the future. Due to their tunable morphologies and superior properties, multifunctional magnetic nanomaterials and their hybrid nanostructures can be designed as specific carriers of drugs, imaging agents, and magnetic theranostics. Multifunctional magnetic nanostructures are promising theranostic agents due to their ability to diagnose and combine therapies. This revisewarch provides a comprehensive overview of the development of advanced multifunctional magnetic nanostructures combining magnetic and optical properties, providing photoresponsive magnetic platforms for promising medical applications. Moreover, this reviewresearchers discusses various innovative developments using multifunctional magnetic nanostructures, including drug delivery, cancer treatment, tumor-specific ligands that deliver chemotherapeutics or hormonal agents, magnetic resonance imaging, and tissue engineering. Additionally, artificial intelligence (AI) can be used to optimize material properties in cancer diagnosis and treatment, based on predicted interactions with drugs, cell membranes, vasculature, biological fluid, and the immune system to enhance the effectiveness of therapeutic agents. Furthermore, this reviewsearch provides an overview of AI approaches used to assess the practical utility of multifunctional magnetic nanostructures for cancer diagnosis and treatment. Finally, the review presents the current knowledge and perspectives on hybrid magnetic systems as cancer treatment tools with AI models.

- magnetic nanostructures

- smart magnetic nanoparticles

- cancer diagnostics

- cancer therapies

- artificial neural network

1. Introduction

2. Magnetic Nanomaterials and Their Magnetic Hybrids Nanostructures (MHNs)

The advent and development of nanomedicine offer new avenues to improve conventional cancer therapies. Magnetic nanomaterials and hybrid nanostructures are set to hold a lot of interest in the future because of their physicochemical properties, adjustable size and shape, and ease of functionalization. In biomedical applications, iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs), especially maghemite and magnetite oxides, ferrites are commonly used because of their ability to decompose in the body and release oxygen and iron [25]. They can be easily excreted from the body after degradation through oxygen transport and metabolic systems.2.1. Morphological Effects of Magnetic Nanomaterials on Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment

When nanoparticles with a diameter of approximately 10 nm are synthesized, they exhibit superparamagnetic properties due to better dispersibility without a magnetic field [26,27][26][27]. Cancer therapy relies on the accumulation of these compounds at a target site in the presence of a magnetic field. The size, shape, and surface coating of magnetic nanoparticles can all play a role in their effectiveness for cancer applications such as drug delivery, imaging, hyperthermia, and theranostics [18,28][18][28]. The size of magnetic nanoparticles can influence their behavior in cancer therapy. Smaller nanoparticles (~10 nm) tend to be more stable and have a higher surface area-to-volume ratio, which can make them more effective for drug delivery and imaging. However, larger nanoparticles (~50 nm) may be more effective in hyperthermia treatment to kill cancer cells by utilizing heat [29]. The shape of magnetic nanoparticles can also influence their behavior in cancer therapy. For example, rod-shaped nanoparticles may be more effective at inducing hyperthermia than spherical nanoparticles. Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) with rod shapes have greater magnetic torque, more intense oscillation, and a greater area involved in the AMF, which results in a higher hyperthermia effect. Moreover, the demagnetization effect indirectly influenced the morphological features through the coercivity of the MNPs. MNPs with rod-shaped shapes had similar saturation magnetic inductions, but their coercivity was 110.42 Gs, which was twice as high as that of spheres (53.185 Gs) [30]. Rod-shaped MNPs consume more energy in vibration than spherical MNPs, i.e., mechanical movement consumes more energy [30,31][30][31]. Furthermore, the surface coating of magnetic nanoparticles can influence their stability, biocompatibility, and ability to target cancer cells. For example, nanoparticles coated with biomolecules, such as antibodies or peptides, may be more effective at targeting cancer cells [32]. On the other hand, smaller MNPs can more easily enter into the cancerous tissues and accumulate at the tumor site due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [32,33][32][33]. Larger MNPs may have a higher payload capacity but may have lesser diffusivity in the tumor tissue. In drug delivery, magnetic nanoparticles with smaller diameters may be able to target cancer cells and release their payloads, such as chemotherapy drugs or gene therapies, more effectively [34]. This can help to minimize the side effects of treatment and improve the overall effectiveness of the therapy. For example, magnetic nanoparticles can be used to deliver chemotherapy drugs to cancer cells or to deliver gene therapies to modify the expression of specific genes in cancer cells. Magnetic nanoparticles can be used for imaging cancer cells in vivo. Smaller magnetic nanoparticles tend to be more effective at producing high-contrast images of cancer cells and tissues, as they have a higher surface area-to-volume ratio and are more susceptible to the magnetic field [35,36,37][35][36][37]. In hyperthermia, larger magnetic nanoparticles may be more effective at inducing heat in cancer cells. This can be achieved by exposing the nanoparticles to an alternating magnetic field, which causes them to oscillate and generate heat. The heat generated by the nanoparticles can then be used to kill cancer cells while minimizing the impact on healthy cells [28]. The quality and effectiveness of MNPs mainly depend on the size and shape of nanoparticles in the final product. The size of the MNPs can be effectively controlled by suitable synthesis methods and reaction conditions. The most important parameters are solvent, pH surfactant, reaction temperature, pressure, residence time, salt source, and precursor. Park et al. reported a large-scale synthesis method for monodisperse nanocrystal synthesis within a size range of 5–22 nm using inexpensive metal salts as reactants in varying solvents [38]. Peng et al. reported the synthesis of self-assembled amorphous core-shell Fe–Fe3O4 nanoparticles within a controlled size-range of 2.5–3.5 nm [39]. Overall, the size of magnetic nanoparticles can play a role in their effectiveness for cancer therapy, depending on the specific application. Further research is needed to fully understand the optimal size of magnetic nanoparticles for different cancer therapy applications. Magnetic nanoparticles have been explored as a potential tool for cancer therapy due to their ability to be selectively delivered to cancer cells and then activated using an external magnetic field [40]. The shape of the magnetic nanoparticles can affect their behavior and performance in cancer therapy applications such as hyperthermia and targeted drug delivery. Several morphologies such as spherical, octahedrons, rods, plates, cubes, rings, hexagons, capsules, wires, tubes, and flower-shaped, depending on the reaction conditions, have been reported in the literature for MNPs suitable for different cancer treatment and therapy applications [40,41][40][41]. The shape of MNPs is a key factor in determining their effectiveness in cancer therapy. Research has shown that MNPs with different shapes can have different properties, such as magnetic moments, surface area, stability, binding affinity with certain drugs, and their ability to deliver a uniform distribution of drug payload [42]. These properties can influence the behavior of the MNPs in the body, as well as their ability to target and treat cancer cells. For example, rod-shaped MNPs may have a higher binding affinity for certain drugs, whereas sphere-shaped MNPs may have a more uniform distribution of drug payload [43]. Magnetic nanoparticles with spherical shapes penetrate tissues better than rods and wires and can reach cancer cells more easily. They may also be more easily activated using a magnetic field, as the longer shape allows for a stronger interaction with the field [44]. Additionally, rod-shaped MNPs may have a higher binding affinity for certain drugs, whereas sphere-shaped MNPs may have a more uniform distribution of drug payload. On the other hand, spherical particles may be more stable and easier to synthesize and may also have a lower toxicity profile [45]. MNPs that are spherical or ellipsoidal tend to have higher stability and lower toxicity compared to MNPs with more complex shapes [46]. This makes them more suitable for use in cancer therapy, as they are less likely to cause side effects. On the other hand, MNPs with more complex shapes, such as rod- or wire-shaped MNPs, tend to have a higher surface area and a stronger magnetic moment. Nanocube morphologies can have a better response for guided chemo-photothermal therapy [47]. This can make them more effective at targeting and treating cancer cells, as they can be more easily manipulated using external magnetic fields. Hyperthermia damages the cancer cells by supplying heat from an external source. For this purpose, magnetic nanoparticles can be used to induce a current in the particles using an alternating magnetic field, which generates heat [32]. The shape of the nanoparticles can affect their heating efficiency and the distribution of heat within the tissue. For example, elongated nanoparticles have been shown to produce more efficient heating than spherical nanoparticles [48]. Targeted drug delivery is another potential application of magnetic nanoparticles in cancer therapy. The nanoparticles can be coated with drugs and directed to specific locations within the body using a magnetic field [49]. The shape of the nanoparticles can affect the stability of the drug coating and the ability of the nanoparticles to reach their target location. For example, nanoparticles with a high aspect ratio (i.e., those that are long and thin) have been shown to have improved targeting ability and stability compared to spherical nanoparticles. Cao et al. reported high drug loading and release efficiency of hierarchically nanostructured magnetic hollow spheres for ibuprofen suggesting the role of shape in drug delivery applications [50]. In addition to their use in magnetic drug targeting, MNPs can also be used in other cancer treatment approaches, such as photothermal therapy, in which MNPs are used to convert light energy into heat to destroy cancer cells. The size and shape of MNPs will influence their ability to absorb and convert light energy, as well as their distribution in the body. Overall, the shape of MNPs plays a critical role in their effectiveness in cancer therapy. By carefully controlling the shape of the MNPs, researchers can optimize their properties and maximize their potential for use in cancer treatment. In particular, the following sections demonstrate the controlled synthesis of MNPs and their functionalization for cancer diagnosis and therapy toward the development of modern medicine.2.2. Polymeric–Magnetic Hybrid Nanostructures

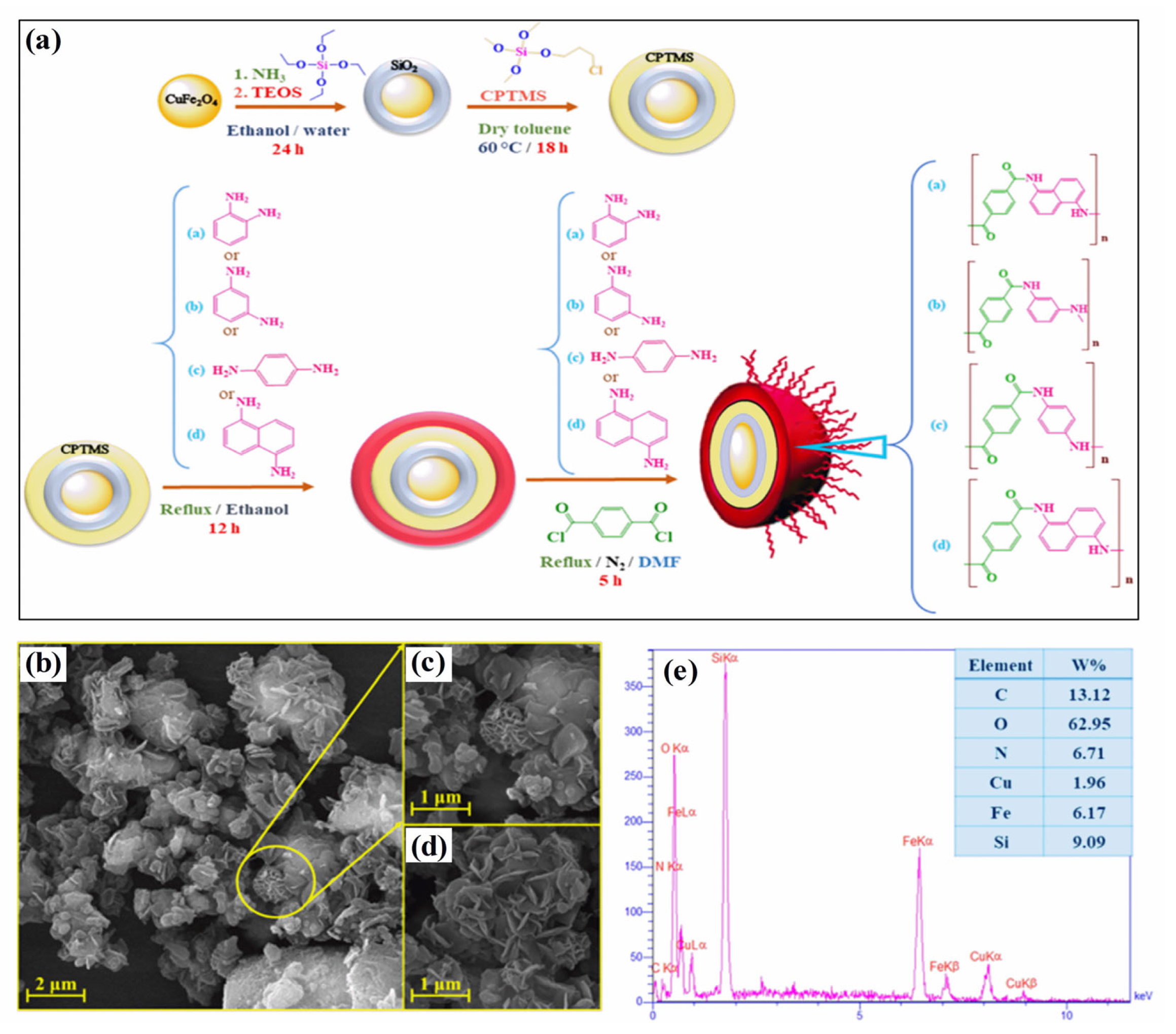

Polymer–magnetic hybrid nanostructures have emerged as a promising approach for cancer treatment due to their unique physicochemical properties [51]. These nanostructures are composed of a polymer matrix and magnetic nanoparticles, which can be functionalized with therapeutic agents such as chemotherapy drugs or imaging agents [52]. The magnetic nanoparticles can be attracted to a specific location in the body using an external magnetic field, allowing for targeted delivery of the therapeutic agents to cancerous tumors [53]. Several methods can be used to synthesize polymer–magnetic hybrid nanostructures for cancer treatment. The most common approaches are layer-by-layer assembly, self-assembly, and co-precipitation. Polymer–magnetic hybrid nanostructures are particularly useful for improving the therapeutic efficacy of chemotherapy drugs [54]. In many cases, chemotherapy drugs are insoluble in water, making it difficult to deliver them to cancerous tumors in the desired concentrations. A polymer matrix can improve the solubility of chemotherapy drugs, leading to higher drug concentrations at the tumor site [55]. Furthermore, the polymer matrix can protect chemotherapy drugs from degradation in the body and prevent side effects. Polymer–magnetic hybrid nanostructures can also improve the targeting of therapeutic agents for cancerous tumors [56]. An external magnetic field can be used to attract nanostructures to a specific location in the body by attaching magnetic nanoparticles to their surfaces. Targeted delivery of therapeutic agents can improve the therapeutic efficacy of the treatment by delivering them to the tumor. Recently, CuFe2O4@SiO2-poly(m-phenylene terephthalamide) nanocomposites have been successfully developed by incorporating poly(m-phenylene terephthalamide) onto CuFe2O4@SiO2 nanostructures, as shown in Figure 1a [46]. The SEM images in Figure 1b–d show a unique nanoflower morphology of CuFe2O4@SiO2-poly(m-phenylene terephthalamide) in the present case, which results from the formation of nanoplates oriented in specific directions. EDX spectra also show copper (1.96%), iron (6.17%), and oxygen (62.95%) peaks, which support the presence of CuFe2O4 cores, as shown in Figure 1e. Spectral analysis confirms the successful polymerization reaction and the formation of p-phenylene terephthalamide chains (13.12%), nitrogen (6.71%), and oxygen (0.72%). TEOS and CPTMS shells are responsible for the presence of the silicon peak (9.09%). This hybrid CuFe2O4@SiO2-poly(m-phenylene terephthalamide) nanostructure shows potential for magnetic hyperthermia while exhibiting low toxicity, making this material promising for cancer diagnosis and therapy.

2.3. Carbon–Magnetic Hybrid Nanostructures

Carbon–magnetic hybrid nanostructures have emerged as a promising approach for cancer treatment [67]. These nanostructures are composed of both carbon-based materials, such as graphene and carbon nanotubes, and magnetic materials, which allow them to be easily manipulated and targeted to specific areas within the body [68]. The potential applications of carbon–magnetic hybrid nanostructures are in the delivery of cancer therapeutics, detection, and diagnosis of cancer [69,70][69][70]. The magnetic material allows the nanostructures to be directed to specific areas within the body using an external magnetic field, whereas the carbon-based material can be used to encapsulate and release the therapeutic agent at a controlled rate [70]. The most widely used carbon-hybrid materials are graphene and carbon nanotubes both of which can be used to deliver cancer therapeutics, such as small interfering RNA (siRNA) molecules, which can help to inhibit the expression of specific genes that are involved in cancer development and progression [71]. Song et al. reported the synthesis of core-shell morphology with 10 nm FeCo and poly(ethylene glycol) decorated graphitic carbon coated on FeCo nanoparticles for enhanced cancer imaging and therapy [72]. Graphitic carbon coating on FeCo prevents FeCo leaching and makes the magnetic nanoparticle more stable, whereas poly(ethylene glycol) coating on functionalized MNP surfaces enhances particle stability, dispersibility, and biocompatibility. Moreover, several hollow carbon nanospheres embedded with γ-Fe2O3 and GdPO4 (Fe–Gd/HCS), dual-Fe nanoparticles embedded within synchronized carbon nanostructures, and co-functionalized mesoporous carbon spheres with γ-Fe2O3 and GdPO4 have also been successfully developed and applied for the integration of magnetic resonance imaging and drug delivery [73,74,75,76,77][73][74][75][76][77]. Multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCN) with magneto-fluorescent carbon quantum dots resulted in synergistic effects toward dual-modal targeted imaging [78]. Poly(acrylic acid) functionalized magnetic multiwall carbon tubes and magnetic-activated carbon particles were synthesized and compared as a nanocarrier for drug delivery and cancer lymphatic-node metastasis treatment. The results suggest poly(acrylic acid) functionalized magnetic multiwall carbon tubes are superior for regression and inhibition of metastasis using gemcitabine loading [79]. Dual functioning magnetic MWCN were also prepared by the addition of iron NPs inside the capillary and surface functionalized with gadolinium using the wet chemical method. The developed magnetic carbon structures can be used in MRI imaging and magnetic hyperthermia applications in cancer treatment [80]. Graphene-oxide hybrid with magnetic material could significantly enhance the efficiency of antitumor efficiencies both in vitro and in vivo through magneto thermal effect and reactive oxygen species-related immunologic effect [81]. These studies demonstrate the potential of carbon–magnetic hybrid nanostructures for cancer treatment and suggest that these nanostructures may be effective for delivering a wide range of cancer therapeutics to specific areas within the body.2.4. Noble-Metal-Based Magnetic Hybrid Nanostructures

Cancer treatment using noble-metal-based magnetic hybrid nanostructures is a promising area of research that holds great potential for improving the effectiveness of cancer therapies. Noble metals, such as gold, silver, platinum, and palladium, have unique chemical and physical properties that make them attractive for use in medicine. These properties, combined with the ability to manipulate their size and shape at the nanoscale, make them ideal candidates for use in cancer treatment. The morphology of the as-prepared nanostructures depends on the synthesis conditions used. Based on the synthesis techniques (such as sol-gel, vacuum sputtering, ion implantation, laser ablation, vacuum evaporation, electrochemical method, two-phase method, seed growth method, and other techniques as described earlier), different morphologies such as rod-like, film, spherical, hierarchical, powder, and other morphologies can be attained [82,83,84,85][82][83][84][85]. The physiochemical properties of noble NPs change as their size and size change [83,84][83][84]. A typical example is the change of absorption spectra of gold NPs for spherical (visible region) and rod-shaped (near-infrared region) structures due to the localized surface plasmon resonance effect [86]. Additionally, the unique photothermal and electronic properties of noble metal NPs are a result of the surface-enhanced Raman scattering and metal-enhanced fluorescence effect that can be useful in cancer diagnostic applications [87,88][87][88]. The most common structures of noble-metal-based magnetic hybrid nanostructures include nanorods, nanoprisms, nanocages, nanowires, nanocubes, hexagonal sheets, and nanospheres [84,89,90,91,92,93][84][89][90][91][92][93]. Gold nanoparticles are being explored to treat tumors by antitumor drug administration, hyperthermia, and angiogenesis inhibition [94]. When exposed to near-infrared light, these nanoparticles have been shown to have a toxic effect on cancer cells. By incorporating these nanoparticles into nanostructures and targeting them in cancer cells, it is possible to use light to trigger the release of the antitumor drug and kill the cancer cells. This approach, known as photothermal therapy, has shown promising results in preclinical studies and is currently being tested in clinical trials. Additionally, gold-based NPs have been utilized in photothermal chemotherapy to kill cancer cells through cell apoptosis and protein denaturation [95,96][95][96]. Song et al. reported the synthesis of hybrid gold nanorods decorated on a mixture of doxorubicin and reduced graphene oxide with excellent photothermal effects. Such a hybrid can effectively be used in hyperthermia and drug delivery applications [97]. Silver nanoparticles have been shown to have a toxic effect on cancer cells and can be used to induce cell death through a process known as apoptosis. In addition, silver nanoparticles have been shown to inhibit the growth of cancer cells, making them potentially useful for preventing the spread of cancer. Bian et al. reported the synthesis of silver nanocages decorated on an octreotide template based on peptide-directed silver mineralization. The particle size and morphology were fine-tuned through the addition of silver nitrate resulting in an optimized surface plasmon resonance behavior. The resulting catalysts were reported to have excellent antitumor properties and photothermal efficiency [98]. Additionally, noble-metal-based magnetic hybrid nanostructures are being used in cancer treatment by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Sun et al. reported the synthesis of surface-modified 64Cu integrated gold nanorods using polyethylene glycol (PEG) and Cu as surface modifiers for enhanced optical imaging and high targetability [99]. In addition to their use in drug delivery and photothermal therapy, noble nanoparticles are also being explored for use in imaging and diagnosis. By incorporating these nanoparticles into contrast agents, it is possible to enhance the visibility of cancerous tumors during imaging procedures such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). This can help doctors to more accurately diagnose and stage cancer, as well as to monitor the effectiveness of treatment. Palladium-based nanostructures have been reported to enhance the photothermal-related process (used in cancer treatment) efficiency and biocompatibility. The inclusion of functionalized palladium structures through polymers significantly improves water dispersion, physiochemical stability, and biocompatibility. Bharathiraja et al. reported the synthesis of chitosan-modified palladium NPs followed by functionalization with RGD peptide resulting in enhanced efficiency of prepared nanoparticles towards near-infrared region imaging for better tumor diagnosis [100]. Hence, noble-metal-based magnetic hybrid nanostructures show great promise for improving the effectiveness of cancer treatment and increasing the chances of survival for cancer patients. Further research is needed to fully understand the potential of these nanostructures and to optimize their use in the clinic. However, these materials have the potential to significantly impact the way that cancer is diagnosed and treated in the future.2.5. Semiconducting Fluorescent Nanomaterials Magnetic Hybrid Nanostructures

Semiconducting fluorescent nanomaterials are a type of nanomaterial that exhibits fluorescent properties when exposed to light [101]. These nanomaterials can absorb and emit light, making them useful for a variety of applications, including cancer diagnostics [102,103][102][103]. The magnetic component of the nanostructure allows it to be guided to the site of the cancer cells using an external magnetic field [104]. Once the nanostructure reaches the cancer cells, the semiconducting fluorescent material can be activated using light, which can then be used to trigger the release of the therapeutic agent [105,106,107][105][106][107]. In photodynamic therapy, the light emitted by the fluorescent nanomaterials activates a photosensitizer, which generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) [108]. These ROS can damage the cancer cells and kill them while minimizing the impact on healthy cells. Semiconducting fluorescent nanomaterial magnetic hybrid nanostructures have several attractive properties for use in cancer treatment, due to their high fluorescence efficiency, tunable emission wavelengths, and ability to be functionalized with a variety of biomolecules [109]. There are several examples of semiconducting fluorescent nanomaterials that have been used in magnetic hybrid nanostructures for cancer treatment. Some of these materials include quantum dots, hybrid nanoparticles, carbon dots, graphene quantum dots, and fluorescent dyes [108]. Quantum dots are nanoscale semiconductor particles that can emit light of different colors depending on their size when excited. They have been used in magnetic hybrid nanostructures for cancer treatment because of their high photostability, which means they can retain their fluorescence over a long period. Hybrid nanoparticles can absorb low-energy light and emit higher-energy light, which makes them useful for photodynamic therapy [110]. They have been incorporated into magnetic hybrid nanostructures for cancer treatment because of their ability to generate ROS when excited. Carbon dots are nanoscale particles made of carbon that have been shown to have fluorescent properties [111]. They have been used in magnetic hybrid nanostructures for cancer treatment because of their biocompatibility and low toxicity. Graphene quantum dots are made of graphene, which is a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice [112]. They have been shown to have fluorescence properties and have been incorporated into magnetic hybrid nanostructures for cancer treatment because of their high stability and low toxicity. Fluorescent dyes are organic molecules that can absorb light at one wavelength and emit it at a different wavelength. Magnetic hybrid nanostructures have been developed for cancer treatment because they can be easily synthesized and have a wide range of emission wavelengths. Fluorescence-based imaging techniques and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) have been used in a variety of cancer diagnostic applications. Lanthanide-doped nanomaterials are materials that are doped with rare earth elements, such as europium or terbium. These materials can emit light when excited and have been explored for use in cancer diagnosis and imaging. Hence, there are many different types of semiconducting fluorescent nanomaterials that have been used in magnetic hybrid nanostructures for cancer treatment, and more are being developed as research in this area continues.2.6. Biomolecular (Genetic Materials Conjugated) Magnetic Hybrid Nanostructures

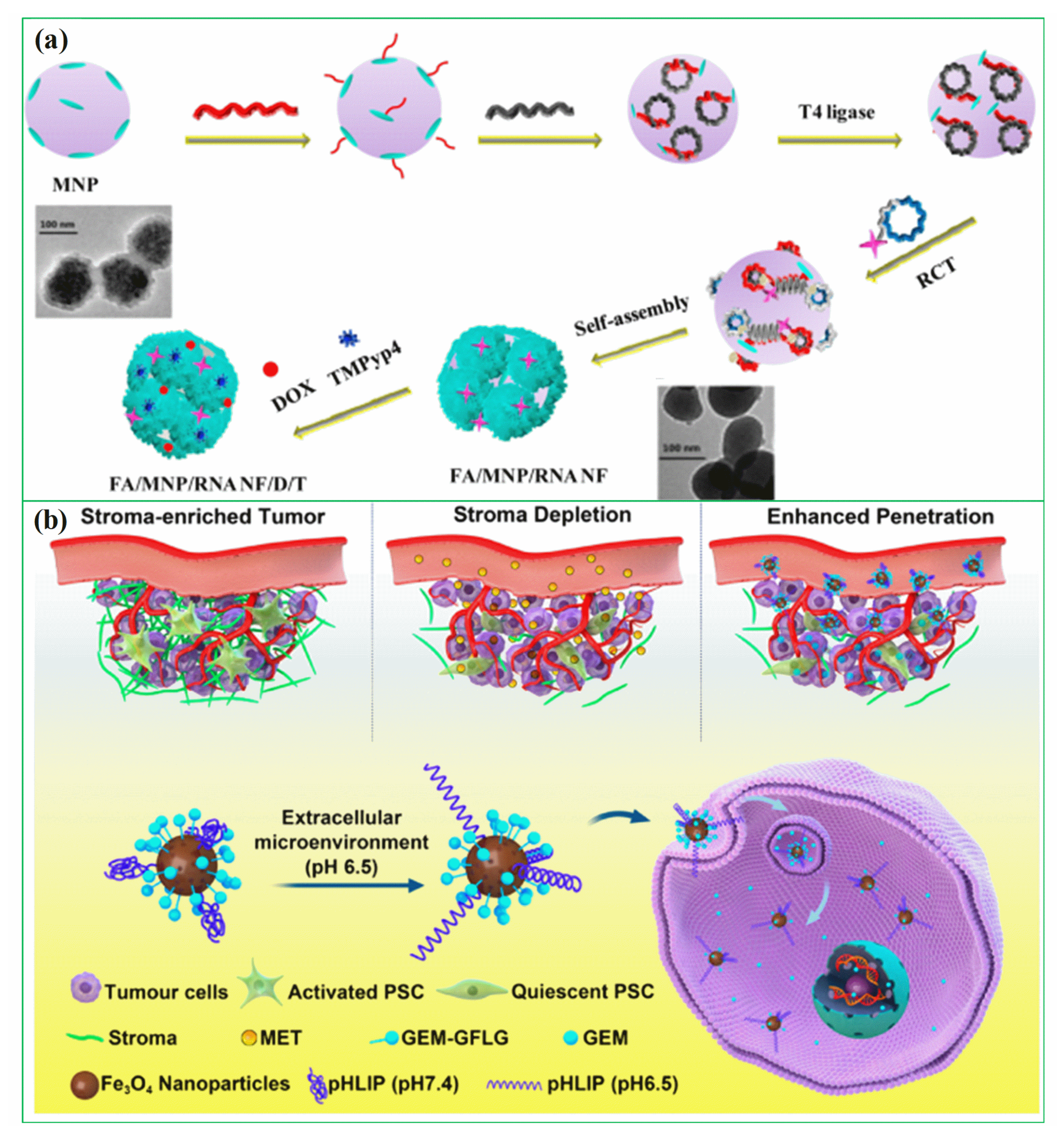

In recent years, researchers have been exploring the use of biomolecules conjugated to magnetic hybrid nanostructures for cancer diagnostics [113,114,115][113][114][115]. There are several examples of biomolecules, such as genetic materials, that can be conjugated into magnetic hybrid nanostructures for use in cancer diagnostics [116,117][116][117]. A new study was developed a magnetic RNA nanoflower delivery system (RNA NF) has been developed to target cancer therapy, as shown in Figure 2a [113]. Nucleic acid can be conveniently separated by introducing magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) instead of the traditional nucleic acid structure. MNP/RNA NF modified with folic acid (FA) demonstrated excellent biocompatibility. This FA/MNP/RNA NF is small in size, easy to synthesize, biocompatible, and has high binding affinity and selectivity, making it ideal for drug delivery, imaging of cancer cells, and biomolecule detection. Moreover, gemcitabine-loaded magnetic nanoparticles have been successfully used in the treatment of pancreatic cancer targeted treatments, as shown schematically in Figure 2b [114]. In this work, PEGylated Fe3O4 nanoparticles with carboxyl groups on the surface were successfully prepared and gemcitabine and peptide (pHLIP) were incorporated to make MET/GEM-MNP-pHLIP. A new cascade treatment for pancreatic cancer utilized MET in an innovative way that could have greatly improved therapeutic outcomes.

References

- Hiam-Galvez, K.J.; Allen, B.M.; Spitzer, M.H. Systemic immunity in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 345–359.

- Preethi, K.A.; Lakshmanan, G.; Sekar, D. Antagomir technology in the treatment of different types of cancer. Future Med. 2021, 13, 481–484.

- Aram, E.; Moeni, M.; Abedizadeh, R.; Sabour, D.; Sadeghi-Abandansari, H.; Gardy, J.; Hassanpour, A. Smart and Multi-Functional Magnetic Nanoparticles for Cancer Treatment Applications: Clinical Challenges and Future Prospects. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3567.

- Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Wu, H.X.; Xu, R.H. Asdvancing to the era of cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Commun. 2021, 41, 803–829.

- Yahya, E.B.; Alqadhi, A.M. Recent trends in cancer therapy: A review on the current state of gene delivery. Life Sci. 2021, 269, 119087.

- Kemp, J.A.; Kwon, Y.J. Cancer nanotechnology: Current status and perspectives. Nano Converg. 2021, 8, 34.

- Zhang, L.; Zhai, B.-Z.; Wu, Y.-J.; Wang, Y. Recent progress in the development of nanomaterials targeting multiple cancer metabolic pathways: A review of mechanistic approaches for cancer treatment. Drug Deliv. 2023, 30, 1–18.

- Lone, S.N.; Nisar, S.; Masoodi, T.; Singh, M.; Rizwan, A.; Hashem, S.; El-Rifai, W.; Bedognetti, D.; Batra, S.K.; Haris, M. Liquid biopsy: A step closer to transform diagnosis, prognosis and future of cancer treatments. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 79.

- Bharath, G.; Rambabu, K.; Banat, F.; Anwer, S.; Lee, S.; BinSaleh, N.; Latha, S.; Ponpandian, N. Mesoporous hydroxyapatite nanoplate arrays as pH-sensitive drug carrier for cancer therapy. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 085409.

- Bharath, G.; Rambabu, K.; Banat, F.; Ponpandian, N.; Alsharaeh, E.; Harrath, A.H.; Alrezaki, A.; Alwasel, S. Shape-controlled rapid synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles and their morphological dependent magnetic and thermal studies for cancer therapy applications. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 066104.

- Bharath, G.; Latha, B.S.; Alsharaeh, E.H.; Prakash, P.; Ponpandian, N. Enhanced hydroxyapatite nanorods formation on graphene oxide nanocomposite as a potential candidate for protein adsorption, pH controlled release and an effective drug delivery platform for cancer therapy. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 240–252.

- Khizar, S.; Ahmad, N.M.; Zine, N.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Errachid-el-salhi, A.; Elaissari, A. Magnetic nanoparticles: From synthesis to theranostic applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 4284–4306.

- Włodarczyk, A.; Gorgoń, S.; Radoń, A.; Bajdak-Rusinek, K. Magnetite Nanoparticles in Magnetic Hyperthermia and Cancer Therapies: Challenges and Perspectives. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1807.

- Hu, H.; Fu, M.; Huang, X.; Huang, J.; Gao, J. Risk factors for lower extremity lymphedema after cervical cancer treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 1713.

- Huo, Y.; Yu, J.; Gao, S. Magnetic nanoparticle-based cancer therapy. In Synthesis and Biomedical Applications of Magnetic Nanomaterials; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2022; pp. 261–290.

- Farzin, A.; Etesami, S.A.; Quint, J.; Memic, A.; Tamayol, A. Magnetic nanoparticles in cancer therapy and diagnosis. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, 1901058.

- Zhu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. Recent advances in magnetic nanocarriers for tumor treatment. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 159, 114227.

- Shen, Z.; Chen, T.; Ma, X.; Ren, W.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, A.; Liu, Y.; Song, J.; Li, Z. Multifunctional theranostic nanoparticles based on exceedingly small magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for T 1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and chemotherapy. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 10992–11004.

- Tan, P.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Wei, Q.; Luo, K. Artificial Intelligence Aids in Development of Nanomedicines for Cancer Management. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 89, 61–75.

- Adir, O.; Poley, M.; Chen, G.; Froim, S.; Krinsky, N.; Shklover, J.; Shainsky-Roitman, J.; Lammers, T.; Schroeder, A. Integrating artificial intelligence and nanotechnology for precision cancer medicine. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1901989.

- Hedayatnasab, Z.; Saadatabadi, A.R.; Shirgahi, H.; Mozafari, M. Heat induction of iron oxide nanoparticles with rational artificial neural network design-based particle swarm optimization for magnetic cancer hyperthermia. Mater. Res. Bull. 2023, 157, 112035.

- Coïsson, M.; Barrera, G.; Celegato, F.; Allia, P.; Tiberto, P. Specific loss power of magnetic nanoparticles: A machine learning approach. APL Mater. 2022, 10, 081108.

- Khan, S.A.; Sharma, R. Super Para-Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPIONs) in the Treatment of Cancer: Challenges, Approaches, and Its Pivotal Role in Pancreatic, Colon, and Prostate Cancer. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2023. (online ahead of print).

- Sohail, A.; Fatima, M.; Ellahi, R.; Akram, K.B. A videographic assessment of Ferrofluid during magnetic drug targeting: An application of artificial intelligence in nanomedicine. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 285, 47–57.

- Materón, E.M.; Miyazaki, C.M.; Carr, O.; Joshi, N.; Picciani, P.H.; Dalmaschio, C.J.; Davis, F.; Shimizu, F.M. Magnetic nanoparticles in biomedical applications: A review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 6, 100163.

- Polenz, M.F.; Sante, L.G.G.; Malschitzky, E.; Bail, A. The challenge to produce magnetic nanoparticles from waste containing heavy metals aiming at biomedical application: New horizons of chemical recycling. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 27, 100678.

- Gribanovsky, S.L.; Zhigachev, A.O.; Golovin, D.Y.; Golovin, Y.I.; Klyachko, N.L. Mechanisms and conditions for mechanical activation of magnetic nanoparticles by external magnetic field for biomedical applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 553, 169278.

- Tong, S.; Quinto, C.A.; Zhang, L.; Mohindra, P.; Bao, G. Size-Dependent Heating of Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 6808–6816.

- Peiravi, M.; Eslami, H.; Ansari, M.; Zare-Zardini, H. Magnetic hyperthermia: Potentials and limitations. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2022, 99, 100269.

- Cheng, D.; Li, X.; Zhang, G.; Shi, H. Morphological effect of oscillating magnetic nanoparticles in killing tumor cells. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 195.

- Mamiya, H.; Fukumoto, H.; Cuya Huaman, J.L.; Suzuki, K.; Miyamura, H.; Balachandran, J. Estimation of magnetic anisotropy of individual magnetite nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 8421–8432.

- Gavilán, H.; Avugadda, S.K.; Fernández-Cabada, T.; Soni, N.; Cassani, M.; Mai, B.T.; Chantrell, R.; Pellegrino, T. Magnetic nanoparticles and clusters for magnetic hyperthermia: Optimizing their heat performance and developing combinatorial therapies to tackle cancer. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 11614–11667.

- Cheng, G. Circulating miRNAs: Roles in cancer diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 81, 75–93.

- Amani, A.; Alizadeh, M.R.; Yaghoubi, H.; Ebrahimi, H.A. Design and fabrication of novel multi-targeted magnetic nanoparticles for gene delivery to breast cancer cells. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102151.

- Park, K.; Lee, S.; Kang, E.; Kim, K.; Choi, K.; Kwon, I.C. New generation of multifunctional nanoparticles for cancer imaging and therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 1553–1566.

- Vangijzegem, T.; Lecomte, V.; Ternad, I.; Van Leuven, L.; Muller, R.N.; Stanicki, D.; Laurent, S. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPION): From Fundamentals to State-of-the-Art Innovative Applications for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 236.

- Darwish, M.S.; Mostafa, M.H.; Al-Harbi, L.M. Polymeric nanocomposites for environmental and industrial applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1023.

- Park, J.; An, K.; Hwang, Y.; Park, J.-G.; Noh, H.-J.; Kim, J.-Y.; Park, J.-H.; Hwang, N.-M.; Hyeon, T. Ultra-large-scale syntheses of monodisperse nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 891–895.

- Peng, S.; Sun, S. Synthesis and Characterization of Monodisperse Hollow Fe3O4 Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 4155–4158.

- Amiri, M.; Salavati-Niasari, M.; Akbari, A. Magnetic nanocarriers: Evolution of spinel ferrites for medical applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 265, 29–44.

- Das, P.; Colombo, M.; Prosperi, D. Recent advances in magnetic fluid hyperthermia for cancer therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 174, 42–55.

- Das, P.; Fatehbasharzad, P.; Colombo, M.; Fiandra, L.; Prosperi, D. Multifunctional magnetic gold nanomaterials for cancer. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 995–1010.

- Knežević, N.Ž.; Gadjanski, I.; Durand, J.-O. Magnetic nanoarchitectures for cancer sensing, imaging and therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 9–23.

- Gul, S.; Khan, S.B.; Rehman, I.U.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, M. A comprehensive review of magnetic nanomaterials modern day theranostics. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 179.

- Stueber, D.D.; Villanova, J.; Aponte, I.; Xiao, Z.; Colvin, V.L. Magnetic nanoparticles in biology and medicine: Past, present, and future trends. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 943.

- Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R.; Asgharnasl, S.; Bani, M.S.; Radinekiyan, F.; Maleki, A.; Mahdavi, M.; Babaniamansour, P.; Bahreinizad, H.; Shalan, A.E.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Magnetic copper ferrite nanoparticles functionalized by aromatic polyamide chains for hyperthermia applications. Langmuir 2021, 37, 8847–8854.

- Xie, W.; Guo, Z.; Gao, F.; Gao, Q.; Wang, D.; Liaw, B.S.; Cai, Q.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Shape-, size- and structure-controlled synthesis and biocompatibility of iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic theranostics. Theranostics 2018, 8, 3284–3307.

- Fatima, H.; Charinpanitkul, T.; Kim, K.-S. Fundamentals to apply magnetic nanoparticles for hyperthermia therapy. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1203.

- Rezaeian, M.; Soltani, M.; Naseri Karimvand, A.; Raahemifar, K. Mathematical modeling of targeted drug delivery using magnetic nanoparticles during intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 324.

- Cao, S.-W.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Ma, M.-Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, L. Hierarchically Nanostructured Magnetic Hollow Spheres of Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3: Preparation and Potential Application in Drug Delivery. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 1851–1856.

- Soares, D.C.F.; Domingues, S.C.; Viana, D.B.; Tebaldi, M.L. Polymer-hybrid nanoparticles: Current advances in biomedical applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110695.

- Mohammed, L.; Ragab, D.; Gomaa, H. Bioactivity of hybrid polymeric magnetic nanoparticles and their applications in drug delivery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 3332–3352.

- Bonilla, A.M.; Gonzalez, P.H. Hybrid polymeric-magnetic nanoparticles in cancer treatments. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 5392–5402.

- Pandita, D.; Kumar, S.; Lather, V. Hybrid poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles: Design and delivery prospectives. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 95–104.

- Hu, X.; Liu, S. Recent advances towards the fabrication and biomedical applications of responsive polymeric assemblies and nanoparticle hybrid superstructures. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 3904–3922.

- Diaconu, A.; Chiriac, A.P.; Neamtu, I.; Nita, L.E. Magnetic Polymeric Nanocomposites. Polym. Nanomater. Nanotherapeutics 2019, 359–386.

- Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Guo, C.; Wang, J.; Ma, J.; Liang, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, H.; Magnetite, T.-R. PEO− PPO− PEO Block Copolymer Nanoparticles for Controlled Drug Targeting Delivery. Langmuir 2007, 23, 12669–12676.

- Ashjari, M.; Panahandeh, F.; Niazi, Z.; Abolhasani, M.M. Synthesis of PLGA–mPEG star-like block copolymer to form micelle loaded magnetite as a nanocarrier for hydrophobic anticancer drug. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 56, 101563.

- Khaledian, M.; Nourbakhsh, M.S.; Saber, R.; Hashemzadeh, H.; Darvishi, M.H. Preparation and evaluation of doxorubicin-loaded pla–peg–fa copolymer containing superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (Spions) for cancer treatment: Combination therapy with hyperthermia and chemotherapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 6167.

- Lee, S.-Y.; Yang, C.-Y.; Peng, C.-L.; Wei, M.-F.; Chen, K.-C.; Yao, C.-J.; Shieh, M.-J. A theranostic micelleplex co-delivering SN-38 and VEGF siRNA for colorectal cancer therapy. Biomaterials 2016, 86, 92–105.

- Chang, D.; Ma, Y.; Xu, X.; Xie, J.; Ju, S. Stimuli-Responsive Polymeric Nanoplatforms for Cancer Therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 707319.

- Jaidev, L.R.; Chellappan, D.R.; Bhavsar, D.V.; Ranganathan, R.; Sivanantham, B.; Subramanian, A.; Sharma, U.; Jagannathan, N.R.; Krishnan, U.M.; Sethuraman, S. Multi-functional nanoparticles as theranostic agents for the treatment & imaging of pancreatic cancer. Acta Biomater. 2017, 49, 422–433.

- Le Fèvre, R.; Durand-Dubief, M.; Chebbi, I.; Mandawala, C.; Lagroix, F.; Valet, J.P.; Idbaih, A.; Adam, C.; Delattre, J.Y.; Schmitt, C.; et al. Enhanced antitumor efficacy of biocompatible magnetosomes for the magnetic hyperthermia treatment of glioblastoma. Theranostics 2017, 7, 4618–4631.

- Rahmani, E.; Pourmadadi, M.; Zandi, N.; Rahdar, A.; Baino, F. pH-Responsive PVA-Based Nanofibers Containing GO Modified with Ag Nanoparticles: Physico-Chemical Characterization, Wound Dressing, and Drug Delivery. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1847.

- Ramnandan, D.; Mokhosi, S.; Daniels, A.; Singh, M. Chitosan, Polyethylene Glycol and Polyvinyl Alcohol Modified MgFe(2)O(4) Ferrite Magnetic Nanoparticles in Doxorubicin Delivery: A Comparative Study In Vitro. Molecules 2021, 26, 3893.

- Taheri-Ledari, R.; Zolfaghari, E.; Zarei-Shokat, S.; Kashtiaray, A.; Maleki, A. A magnetic antibody-conjugated nano-system for selective delivery of Ca(OH)2 and taxotere in ovarian cancer cells. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 995.

- Boncel, S.; Herman, A.P.; Walczak, K.Z. Magnetic carbon nanostructures in medicine. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 31–37.

- Bagheri, A.R.; Aramesh, N.; Bilal, M.; Xiao, J.; Kim, H.-W.; Yan, B. Carbon nanomaterials as emerging nanotherapeutic platforms to tackle the rising tide of cancer–A review. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2021, 51, 116493.

- Han, C.; Zhang, A.; Kong, Y.; Yu, N.; Xie, T.; Dou, B.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, K. Multifunctional iron oxide-carbon hybrid nanoparticles for targeted fluorescent/MR dual-modal imaging and detection of breast cancer cells. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1067, 115–128.

- Pooresmaeil, M.; Namazi, H. Fabrication of a smart and biocompatible brush copolymer decorated on magnetic graphene oxide hybrid nanostructure for drug delivery application. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 142, 110126.

- Charbe, N.B.; Amnerkar, N.D.; Ramesh, B.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Bakshi, H.A.; Aljabali, A.A.A.; Khadse, S.C.; Satheeshkumar, R.; Satija, S.; Metha, M.; et al. Small interfering RNA for cancer treatment: Overcoming hurdles in delivery. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 2075–2109.

- Song, G.; Kenney, M.; Chen, Y.-S.; Zheng, X.; Deng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.X.; Gambhir, S.S.; Dai, H.; Rao, J. Carbon-coated FeCo nanoparticles as sensitive magnetic-particle-imaging tracers with photothermal and magnetothermal properties. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 325–334.

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, T.; Lu, M.; Chen, Z.; Jia, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ling, Y.; Zhou, Y. Hollow carbon nanospheres embedded with stoichiometric γ-Fe 2 O 3 and GdPO 4: Tuning the nanospheres for in vitro and in vivo size effect evaluation. Nanoscale Adv. 2022, 4, 1414–1421.

- Zhang, H.; Wu, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Ling, Y.; Jia, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y. Hollow carbon nanospheres dotted with Gd–Fe nanoparticles for magnetic resonance and photoacoustic imaging. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 10943–10952.

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Ling, Y.; Zhou, Y. In situ embedding dual-Fe nanoparticles in synchronously generated carbon for the synergistic integration of magnetic resonance imaging and drug delivery. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 5296–5304.

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, P.; Ling, Y.; Li, X.; Xia, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Y. Single Molecular Wells–Dawson-Like Heterometallic Cluster for the In Situ Functionalization of Ordered Mesoporous Carbon: AT 1-and T 2-Weighted Dual-Mode Magnetic Resonance Imaging Agent and Drug Delivery System. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1605313.

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Ling, Y.; Zhou, Y. Preparation of highly dispersed γ-Fe 2 O 3 and GdPO 4 co-functionalized mesoporous carbon spheres for dual-mode MR imaging and anti-cancer drug carrying. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 3765–3770.

- Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, N.; Shen, J. Magnetofluorescent Carbon Quantum Dot Decorated Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes for Dual-Modal Targeted Imaging in Chemo-Photothermal Synergistic Therapy. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 151–162.

- Yang, F.; Jin, C.; Yang, D.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Di, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, C.; Ni, Q.; Fu, D. Magnetic functionalised carbon nanotubes as drug vehicles for cancer lymph node metastasis treatment. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 1873–1882.

- Peci, T.; Dennis, T.J.S.; Baxendale, M. Iron-filled multiwalled carbon nanotubes surface-functionalized with paramagnetic Gd (III): A candidate dual-functioning MRI contrast agent and magnetic hyperthermia structure. Carbon 2015, 87, 226–232.

- Liu, X.; Yan, B.; Li, Y.; Ma, X.; Jiao, W.; Shi, K.; Zhang, T.; Chen, S.; He, Y.; Liang, X.-J.; et al. Graphene Oxide-Grafted Magnetic Nanorings Mediated Magnetothermodynamic Therapy Favoring Reactive Oxygen Species-Related Immune Response for Enhanced Antitumor Efficacy. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 1936–1950.

- Ma, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, H.; Peng, M.; Dong, G.; Yu, X.; Yang, J. Sol-gel preparation of Ag-silica nanocomposite with high electrical conductivity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 436, 732–738.

- Rodrigues, T.S.; da Silva, A.G.M.; Camargo, P.H.C. Nanocatalysis by noble metal nanoparticles: Controlled synthesis for the optimization and understanding of activities. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 5857–5874.

- Zhao, R.; Xiang, J.; Wang, B.; Chen, L.; Tan, S. Recent Advances in the Development of Noble Metal NPs for Cancer Therapy. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2022, 2022, 2444516.

- Ye, W.; Yan, J.; Ye, Q.; Zhou, F. Template-Free and Direct Electrochemical Deposition of Hierarchical Dendritic Gold Microstructures: Growth and Their Multiple Applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 15617–15624.

- Melancon, M.P.; Zhou, M.; Li, C. Cancer Theranostics with Near-Infrared Light-Activatable Multimodal Nanoparticles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 947–956.

- Xie, W.; Schlücker, S. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopic detection of molecular chemo- and plasmo-catalysis on noble metal nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2326–2336.

- Pawar, S.; Bhattacharya, A.; Nag, A. Metal-Enhanced Fluorescence Study in Aqueous Medium by Coupling Gold Nanoparticles and Fluorophores Using a Bilayer Vesicle Platform. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 5983–5990.

- Seo, B.; Lim, K.; Kim, S.S.; Oh, K.T.; Lee, E.S.; Choi, H.-G.; Shin, B.S.; Youn, Y.S. Small gold nanorods-loaded hybrid albumin nanoparticles with high photothermal efficacy for tumor ablation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 179, 340–351.

- Phan, T.T.V.; Nguyen, V.T.; Ahn, S.-H.; Oh, J. Chitosan-mediated facile green synthesis of size-controllable gold nanostars for effective photothermal therapy and photoacoustic imaging. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 118, 492–501.

- Manivasagan, P.; Khan, F.; Hoang, G.; Mondal, S.; Kim, H.; Hoang Minh Doan, V.; Kim, Y.-M.; Oh, J. Thiol chitosan-wrapped gold nanoshells for near-infrared laser-induced photothermal destruction of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 225, 115228.

- Lin, G.; Dong, W.; Wang, C.; Lu, W. Mechanistic study on galvanic replacement reaction and synthesis of Ag-Au alloy nanoboxes with good surface- enhanced Raman scattering activity to detect melamine. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 263, 274–280.

- Huang, X.; Tang, S.; Mu, X.; Dai, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhou, Z.; Ruan, F.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, N. Freestanding palladium nanosheets with plasmonic and catalytic properties. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 28–32.

- Huang, W.; Xing, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhuo, J.; Cai, M. Sorafenib derivatives-functionalized gold nanoparticles confer protection against tumor angiogenesis and proliferation via suppression of EGFR and VEGFR-2. Exp. Cell Res. 2021, 406, 112633.

- Wang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Lin, S.; Huang, J.; Dai, J.; Jiang, Q.; Cheng, D.; Shuai, X. Photothermo-chemotherapy of cancer employing drug leakage-free gold nanoshells. Biomaterials 2016, 78, 40–49.

- Gao, F.; Sun, M.; Xu, L.; Liu, L.; Kuang, H.; Xu, C. Biocompatible Cup-Shaped Nanocrystal with Ultrahigh Photothermal Efficiency as Tumor Therapeutic Agent. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1700605.

- Song, J.; Yang, X.; Jacobson, O.; Lin, L.; Huang, P.; Niu, G.; Ma, Q.; Chen, X. Sequential Drug Release and Enhanced Photothermal and Photoacoustic Effect of Hybrid Reduced Graphene Oxide-Loaded Ultrasmall Gold Nanorod Vesicles for Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9199–9209.

- Bian, K.; Zhang, X.; Liu, K.; Yin, T.; Liu, H.; Niu, K.; Cao, W.; Gao, D. Peptide-Directed Hierarchical Mineralized Silver Nanocages for Anti-Tumor Photothermal Therapy. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 7574–7588.

- Sun, X.; Huang, X.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Jacobson, O.; Liu, D.; Szajek, L.P.; Zhu, W.; Niu, G.; et al. Chelator-Free 64Cu-Integrated Gold Nanomaterials for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging Guided Photothermal Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 8438–8446.

- Bharathiraja, S.; Bui, N.Q.; Manivasagan, P.; Moorthy, M.S.; Mondal, S.; Seo, H.; Phuoc, N.T.; Vy Phan, T.T.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.D.; et al. Multimodal tumor-homing chitosan oligosaccharide-coated biocompatible palladium nanoparticles for photo-based imaging and therapy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 500.

- Ding, X.; Li, D.; Jiang, J. Gold-based inorganic nanohybrids for nanomedicine applications. Theranostics 2020, 10, 8061.

- Pirsaheb, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Salimi, A.; Payandeh, M. Functionalized fluorescent carbon nanostructures for targeted imaging of cancer cells: A review. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 231.

- Chen, M.; Yin, M. Design and development of fluorescent nanostructures for bioimaging. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 365–395.

- Karan, N.S.; Keller, A.M.; Sampat, S.; Roslyak, O.; Arefin, A.; Hanson, C.J.; Casson, J.L.; Desireddy, A.; Ghosh, Y.; Piryatinski, A. Plasmonic giant quantum dots: Hybrid nanostructures for truly simultaneous optical imaging, photothermal effect and thermometry. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 2224–2236.

- Wang, D.; Zhou, J.; Chen, R.; Shi, R.; Zhao, G.; Xia, G.; Li, R.; Liu, Z.; Tian, J.; Wang, H. Controllable synthesis of dual-MOFs nanostructures for pH-responsive artemisinin delivery, magnetic resonance and optical dual-model imaging-guided chemo/photothermal combinational cancer therapy. Biomaterials 2016, 100, 27–40.

- Chen, M.-L.; He, Y.-J.; Chen, X.-W.; Wang, J.-H. Quantum dots conjugated with Fe3O4-filled carbon nanotubes for cancer-targeted imaging and magnetically guided drug delivery. Langmuir 2012, 28, 16469–16476.

- Shen, J.-M.; Guan, X.-M.; Liu, X.-Y.; Lan, J.-F.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, H.-X. Luminescent/magnetic hybrid nanoparticles with folate-conjugated peptide composites for tumor-targeted drug delivery. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012, 23, 1010–1021.

- Zhou, Z.; Song, J.; Nie, L.; Chen, X. Reactive oxygen species generating systems meeting challenges of photodynamic cancer therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 6597–6626.

- Choi, J.; Sun, I.-C.; Hwang, H.S.; Yoon, H.Y.; Kim, K. Light-triggered Photodynamic Nanomedicines for Overcoming Localized Therapeutic Efficacy in Cancer Treatment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 186, 114344.

- Matiushkina, A.; Litvinov, I.; Bazhenova, A.; Belyaeva, T.; Dubavik, A.; Veniaminov, A.; Maslov, V.; Kornilova, E.; Orlova, A. Time-and Spectrally-Resolved Photoluminescence Study of Alloyed CdxZn1− xSeyS1− y/ZnS Quantum Dots and Their Nanocomposites with SPIONs in Living Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4061.

- Molaei, M.J.; Salimi, E. Magneto-fluorescent superparamagnetic Fe3O4@ SiO2@ alginate/carbon quantum dots nanohybrid for drug delivery. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 288, 126361.

- Hassani, S.; Gharehaghaji, N.; Divband, B. Chitosan-coated iron oxide/graphene quantum dots as a potential multifunctional nanohybrid for bimodal magnetic resonance/fluorescence imaging and 5-fluorouracil delivery. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103589.

- Guo, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S. Diagnosis–Therapy integrative systems based on magnetic RNA nanoflowers for Co-drug delivery and targeted therapy. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 2267–2274.

- Han, H.; Hou, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, P.; Kang, M.; Jin, Q.; Ji, J.; Gao, M. Metformin-induced stromal depletion to enhance the penetration of gemcitabine-loaded magnetic nanoparticles for pancreatic cancer targeted therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 4944–4954.

- Hadinoto, K.; Sundaresan, A.; Cheow, W.S. Lipid–polymer hybrid nanoparticles as a new generation therapeutic delivery platform: A review. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013, 85, 427–443.

- Huang, X.; Blum, N.T.; Lin, J.; Shi, J.; Zhang, C.; Huang, P. Chemotherapeutic drug–DNA hybrid nanostructures for anti-tumor therapy. Mater. Horiz. 2021, 8, 78–101.

- Dalmina, M.; Pittella, F.; Sierra, J.A.; Souza, G.R.R.; Silva, A.H.; Pasa, A.A.; Creczynski-Pasa, T.B. Magnetically responsive hybrid nanoparticles for in vitro siRNA delivery to breast cancer cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 99, 1182–1190.