Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 3 by Conner Chen.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a worldwide chronic disease that can cause severe inflammation to damage the surrounding tissue and cartilage. There are many different factors that can lead to osteoarthritis, but abnormally progressed programmed cell death is one of the most important risk factors that can induce osteoarthritis. Prior studies have demonstrated that programmed cell death, including apoptosis, pyroptosis, necroptosis, ferroptosis, autophagy, and cuproptosis, has a great connection with osteoarthritis.

- programmed cell death

- osteoarthritis

- pathogenesis

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis is a chronic disease [1] involving inflammatory reactions [2] that mainly damage the surrounding tissue and cartilage [3]. The effect of osteoarthritis on cartilage leads to many other diseases as well as increases the severity of osteoarthritis itself [4]. The most common symptom of osteoarthritis is pain; in the early stages of the disease, pain is felt mainly upon exercise, while later stages are characterized by pressing pain and continuous pain [5]. In addition, osteoarthritis causes joint stiffness and loss of motor function [6], resulting in loss of confidence and self-abasement [6][7]. There are many risk factors for osteoarthritis, including dyslipidemia and type Ⅱ diabetes [8], high-intensity joint impact [4], lack of antioxidants [4], high bone mineral density, and high age [9]. Recently, several studies on the correlation between programmed cell death and osteoarthritis have revealed that programmed cell death may be an important risk factor for osteoarthritis.

Programmed cell death (PCD) is an active mode of cell death that is regulated by various genes. All types of programmed cell death play an important role in the development of an organism, and uncontrolled programmed cell death can cause developmental damage. For example, uncontrolled programmed cell death can cause neurological diseases [10], such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, as well as cancer. Uncontrolled programmed cell death is also a risk factor for secondary osteoarthritis.

Programmed cell death may be lytic or non-lytic [11], The main type of non-lytic cell death, wherein cell contents don’t overflow upon cell death, is apoptosis. In apoptosis, cell growth and development stop, and a cell undergoes a controlled death [12]. There are two main pathways that mediate apoptotic cell death, intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. In many osteoarthritis cases, apoptosis is found to occur in the arthrodial cartilage [13]. Pyroptosis is another important type of programmed cell death [14], which causes membrane perforation, nuclear condensation, and chromosomal lysis [15]. Pyroptosis in osteoblasts can cause loss of arthrodial cartilage, leading to osteoarthritis. Ferroptosis is a type of programmed cell death in which iron and reactive oxygen species (ROS) cause structural changes in mitochondria, such as cleavage of the outer mitochondrial membrane and degeneration of mitochondrial cristae [16][17][18][19][20][21]. Although there are only a few studies on the relationship between ferroptosis and osteoarthritis (OA), it has been shown that, in cartilage cells, ferrostatin-1 can decrease the activity of ferroptosis-related proteins [22]. Unlike necrosis, which is caused by wounds, necroptosis is a type of caspase-independent programmed cell death [23]. Autophagy eliminates internal aggregates of damaged cells, such as aggregates of misfolded proteins, as well as senescent or damaged organelles [24]. The process of autophagy starts with the formation of an isolation membrane by the endoplasmic reticulum and the trans-Golgi network [25]. This isolation membrane then wraps around the protein aggregates and damaged and senescent organelles, enabling their fusion with lysosomes [26]. The lysosomal enzymes can then break these components down so that they can be reused to produce new proteins and organelles; autophagy is thus called a “recycling factory” [27][28][29]. In general, different types of programmed cell death play different roles in OA. Most of these, such as apoptosis, pyroptosis, cuproptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis, can induce or exacerbate OA. Autophagy can inhibit the exacerbation of OA and, thereby, protect cartilage. Due to these functions of PCD, there has been research into the discovery of drugs targeting signal pathways involved in various types of PCD in order to treat or relieve the symptoms of OA.

There are currently many treatment options for osteoarthritis. The main therapeutic prescription for OA involves conservative treatments to reduce symptoms. However, this treatment strategy does not treat OA at the source. Therefore, drugs targeting programmed cell death, such as anti-cytokine drugs, can be a good option for treating the OA pathology [30].

2. Mechanisms of Cell Death in Osteoarthritis

2.1. Apoptosis

Lacunar emptying and reduced cell density in osteoarthritic cartilage were discovered through histological analysis, suggesting that cell death may occur in this cartilage throughout the duration of OA and may even contribute to OA development [31][32]. A positive correlation was found between the number of apoptotic chondrocytes and the extent of OA-mediated degradation in the human cartilage [33]. The apoptosis of chondrocytes and inflammatory responses are important factors in the pathogenesis of OA, with osteoarthritic chondrocytes releasing inflammatory mediators, including, Interleukin-1β(IL-1β), Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), prostaglandins, and nitric oxide (NO) [34][35].

Chondrocyte destruction, involving inflammation and apoptosis, is facilitated by mitochondrial malfunctioning brought on by excessive oxidative stress, abnormalities in the respiratory chain, and an imbalance in the mitochondrial dynamics [36]. Excess superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and NO, resulting from elevated oxidative stress due to intrinsic apoptosis, are crucial in the pathogenesis of OA [37][38].

Immunostaining of human OA cartilage with anti-nitrotyrosine antibodies revealed that the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) enzyme is upregulated in OA chondrocytes, resulting in the excess production of NO in the cartilage [39][40]. Both endogenous and exogenous NO can induce apoptosis through a mitochondria-dependent mechanism [41][42], involving the obstruction of mitochondrial respiration and production of cytochrome C (Cyt C) and caspase-9 [43]. The phosphate-dependent apoptosis of chondrocytes is also mediated by NO [44]. The inner mitochondrial membrane contains a large conductance channel called PTP [45]. Both high calcium and ROS levels can cause PTP to open, inducing mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MMP) loss [46][47]. It was found that mitochondrial dysfunction, including increased mitochondrial membrane permeability and decreased MMP expression, can promote cytochrome C (Cyt-C) migration from the mitochondrial matrix to the cytoplasm [48], triggering apoptosis through caspase activation and raising the BAX/Bcl-2 ratio [49]. One study showed that, due to the increased ROS burden of aged chondrocytes, OA patients had greater mtDNA damage than individuals with normal chondrocytes [50][51][52]. STING expression was found to be significantly increased in both human and mouse OA tissues and chondrocytes exposed to IL-1β. STING overexpression increased apoptosis in both chondrocytes treated and untreated with IL-1β [53].

As an inflammatory factor, IL-1β plays an extremely important role in the development of osteoarthritis [54][55][56]. In the OA tissues of both humans and mice, as well as in chondrocytes exposed to IL-1β, the expression of STING was noticeably increased. Moreover, an increase in the expression of STING could induce apoptosis by inducing extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation [57].

TRAIL, which can bind to death receptors exposed on the cell surface to trigger apoptosis, can directly cause chondrocyte apoptosis via the extrinsic pathway; in an experimental OA rat model, TRAIL and DR4 were found to be overexpressed in the cartilage [58][59]. These findings indicated that trail-induced chondrocyte apoptosis influences OA pathogenesis.

Many non-coding RNAs, including long-noncoding RNAs and circular RNAs, can regulate chondrocyte apoptosis through different mechanisms. Some of the mechanisms that can promote chondrocyte apoptosis involve Circ_0136474 [60][61], long non-coding RNA plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 [62], LINC00707 [63], and CircZNF652E [64]; the mechanisms that can prevent chondrocyte apoptosis include circANKRD36 [65], long noncoding RNA NAV2-AS5 [66], and circ_0020014 [67]. Circular RNAs act as sponges for miRNAs to suppress their activity and, thereby, regulate the expression of their downstream target genes [68]. The OA cartilage expresses miR-146a upon being triggered by a variety of microbes and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IFN-α and IL-1β [69][70]. For instance, miR-146a-5p expression significantly increased caspase-3 activation, PARP degradation, and Bax expression while repressing Bcl-2 expression in human OA tissues, thereby accelerating the chondrocyte apoptosis [69]. MiR-146a could increase human chondrocyte apoptosis by specifically suppressing Smad4 expression in mechanically damaged cartilage [71].

2.2. Pyroptosis

Pyroptosis is a type of lytic cell death that has many characteristics in common with and many characteristics different from apoptosis. During pyroptosis, the cell first expands and then generates gigantic bubbles from the plasma membrane [72][73]. Pyroptosis is primarily caused by two pathways: the canonical inflammasome pathway, which is mediated by caspase-1, and the non-canonical pathway, which is mediated by caspases 4, 5, and 11 [74]. In the canonical inflammasome pathway, the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome induces pyroptotic cell death through Gasdermin D (GSDMD), the release of which is dependent on caspase-1 [75]. Many risk factors for osteoarthritis, such as obesity, basic calcium phosphate (BCP), and aging, can activate NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and, thus, induce OA [76]. The level of pyroptosis-associated inflammasomes is high in the articular fluid of patients with OA and can increase the levels of IL-1β and IL-18, both of which can increase cartilage cell pyroptosis and inflammatory responses in osteoarthritis [76]. The pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 also play a role in the induction of pain in OA and hyperalgesia. Some inhibitors of NLRP3 inflammasomes, such as CY-09, can significantly inhibit OA deterioration and alleviate the OA development [77]. P2X7 purinergic receptor (P2X7R) can also aid NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and, thereby, cause pyroptosis [78]. Furthermore, pyroptosis not only directly leads to OA but also interacts with other kinds of PCD, such as apoptosis, to promote osteoarthritis. For example, excessive production of apoptotic bodies and increased calcification of cartilage tissue can induce pyroptosis and, thereby, exacerbate OA [79]. During OA development, pyroptosis can cause pathological changes in joints affected by inflammation, such as cartilaginous defects, cartilage fracture, and arthromeningitis [80].

2.3. Necroptosis

Necroptosis, which is mediated by Receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1(RIPK1) and Receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 3(RIPK3), has a mechanism similar to that of apoptosis and a morphology similar to that of necrosis [81][82]. A well-known necroptosis-inducing pathway is Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1(TNFR1) signaling through the complex IIb [83]. Complex IIa can be transformed into complex IIb, which is made up of RIPK1, RIPK3, FADD, and caspase-8; when CASP8 is blocked, complex IIb can develop into a necrosome [84]. The presence of necroptotic chondrocytes in fractured human and mouse cartilages was revealed by immunohistochemical staining for markers of necroptosis, including RIP3, p-MLKL, and MLKL [85]. According to earlier studies, the processes of necroptosis and cartilage destruction may be related to oxidative stress and cytokine generation in OA [86][87][88]; RIPK plays a part in all forms of osteoarthritis. Oxidative stress is a key mediator of programmed necrosis in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis and has a significant impact on the disease. Cartilage breakdown was found to be accelerated by TNF- and RIPK1/RIPK3-mediated programmed necrosis. The programmed necrosis pathway was strengthened when apoptosis was suppressed [89]. However, the TRIM24-RIP3 axis also allows RIP3 to function in cartilage in an MLKL-independent manner [85]. Another study hypothesized that the TLR-TRIF-RIP3-IL-1β axis enhances arthritis development independently of MLKL [90].

As a primary regulator of cell death, in the presence of appropriate downstream signals, RIP1 promotes not only necroptosis but also apoptosis, unlike RIP3, which predominantly mediates necroptosis [91]. A study by Cheng recently suggested that RIP1 expression is considerably increased in the cartilage of OA patients and OA rat models and provided in vivo evidence that overexpression of intra-articular RIP1 is enough to trigger rat OA symptoms; these findings emphasized the critical function of RIP1 in OA development through the regulation of chondrocyte necroptosis and ECM breakdown. Interestingly, bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7) was discovered as a new downstream target of RIP1 in chondrocytes, revealing a non-canonical necroptosis regulation method; moreover, it was found that MLKL is not necessary for OA pathogenesis and chondrocyte necroptosis induced by RIP1 [92]. However, the physiological and pathological roles of RIP3 and RIPK1 in cartilage are yet to be investigated, and it is unknown whether RIP3-mediated or RIPK1-mediated necroptosis regulation is involved in OA etiology [92][93].

2.4. Ferroptosis

Ferroptosis is a kind of iron-dependent programmed cell death that mainly affects the structures of cellular organelles, especially the mitochondrial structure, and is characterized by the accumulation of lipid peroxides [94]. In ferroptosis, iron accumulation can increase ROS production [95]. These ROS can then induce the peroxidation of lipids on the outer mitochondrial membrane, leading to cell death [96]. In vitro control experiments revealed that the iron ion concentration in the cartilage synovial fluid was significantly higher, and the glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX 4) content in the cartilage was lower in the osteoarthritis group compared to that in the normal group [96]. GPX4 was found to protect chondrocytes by inhibiting the OA-related ferroptosis [97]. The inactivity of the lipid repair enzyme GPX4 can lead to an increase in the lipid-based reactive oxygen species content and, thus, induce ferroptosis [4]. In ferroptosis, iron plays a catalytic role. For example, iron can catalyze LOXs, which are important for phospholipid peroxidation-related metabolism [98]. Moreover, ferroptosis can increase the expression of MMP13 and decrease the expression of collagen Ⅱ [94]. Matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP13) is an important enzyme involved in arthrodial cartilage degeneration, and cartilage ECM degeneration is a hallmark of osteoarthritis [99]. Through clinical experiments, Yao et al. showed that ferrostatin-1 could decrease the expression of ferroptosis-related proteins to inhibit ferroptosis and thereby relieve OA symptoms [22].

2.5. Autophagy

Autophagy is another type of programmed cell death that plays an important role in OA. The main regulatory factor of autophagy is mTOR. mTOR can inhibit autophagy by phosphorylating ULK1, which inhibits the function of AMPK in the ULK1 [100]. The main function of AMPK in ULK1 is that the AMPK can phosphorylate ULK1. Using cell autophagy, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit type 3 (PlK3C3), the mammalian ortholog of yeast Vps34, can phosphorylate PIP2 to PI3P, which is necessary for recruiting autophagic vacuoles [101]. Autophagy is important for OA development. First, chondrocyte autophagy can regulate various chondrocyte activities [102]. Moreover, autophagy can break down misfolded proteins and damaged organelles in cartilage cells for recycling and, thereby, mitigate the development of osteoarthritis [103]. Although mTOR signaling pathway activation is essential for cartilage development, in a mouse model of OA, mTOR signaling pathway overexpression in autophagic cells could induce OA. One study showed that the activation of AMPK by metformin could relieve OA symptoms, as AMPK can inhibit mTORC1 activity. Moreover, their overall effect can induce autophagy to inhibit the senescence of the chondrocytes and the development of OA [104]. Autophagy can be used to break down the source of intracellular ROS. An important step in OA development is ROS, acting as a second message to induce mitochondrial damage and ER activation [105]. If the autophagy of cells with mitochondrial damage (mitophagy) does not occur, excess ROS are released from them and induce abnormal cell death, leading to OA [106]. Many risk factors for OA, such as high-intensity impact, inflammatory cytokines, and high age, can increase ROS in the chondrocytes [107]. Moreover, autophagy is important for mesenchymal stem cells, and mesenchymal stem cells are crucial for the stabilization and repair of cartilage tissue [101].

2.6. Cuproptosis

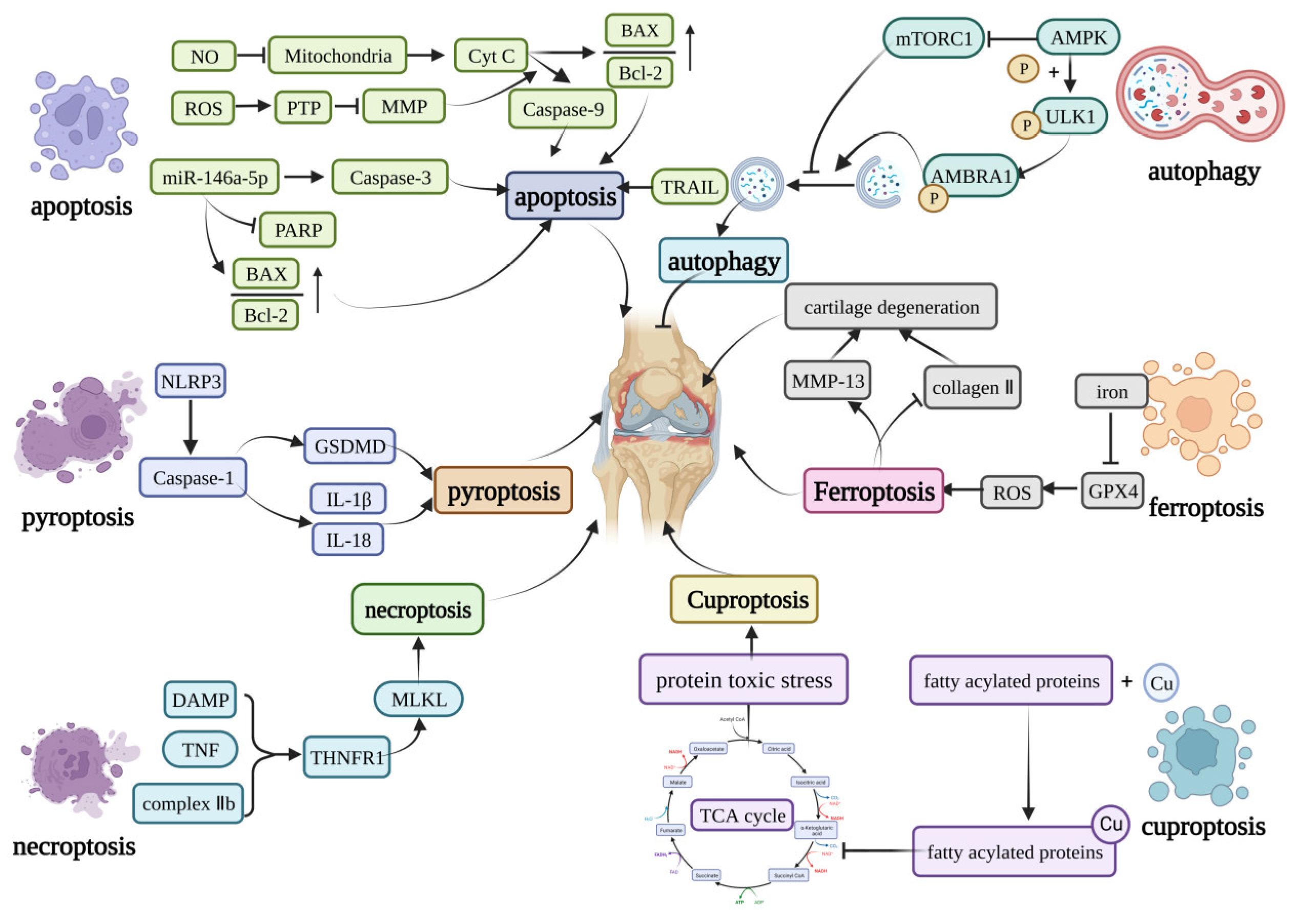

Copper and other trace elements are essential for the body. It is critical for these metals to be present in sufficient quantities in cells [108]. Dysregulation of the intracellular bioavailability of copper, a critical cofactor, can cause oxidative stress and cytotoxicity [109]. Excess copper, for example, disturbs the iron–sulfur cofactors and promotes the formation of hazardous reactive oxygen species via accelerating Fenton reactions [110]. The known cellular mechanisms and enzymatic targets of Cu, however, fall short of adequately explaining the cellular response to the Cu toxicity [108]. The fundamental cause of copper-related cell death is the intracellular buildup of copper ions, which bind to and aggregate the fatty acylated proteins involved in the TCA cycle. Blocking of the TCA cycle by Cu ions causes protein toxic stress, which results in cell death [111]. Further research is necessary to properly understand the precise mechanisms underlying cuproptosis. SLC31A1, PDHB, PDHA1, LIPT1, LIAS, DLD, FDX1, DLST, DLAT, and DBT are the top 10 cuprotosis genes linked to immune infiltration in osteoarthritis. TResults of theis study involving a risk model showed that the copper cell death gene PDHB might be a risk factor for osteoarthritis. Two E1 isoforms of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, PDHB, and PDHA1, are mostly present in cellular mitochondria and catalyze the conversion of glucose-derived pyruvate to acetyl-coA [112][113][114]. A mouse study of osteoarthritis also revealed that high acetyl-coA buildup, induced by matrix metalloproteinases, led to significant cartilage degeneration and chondrocyte apoptosis [115]. LIPT1 and LIAS are both involved in the production of mitochondrial fatty acids [116]. According to one study, the role of free fatty acids in subchondral bone injury may be more dependent on the inflammatory response and immune system than on related signaling pathways [117]. Based on the findings of the abovementioned studies, it can be hypothesized that copper cell death genes are crucial for immune infiltration in osteoarthritis; however, there have been few investigations into the involvement of copper cell death-related genes in the immune regulation of osteoarthritis. Antigen-presenting cells, mast cells, dendritic cells, and chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) may have significant effects on the regulation of copper cell death genes in osteoarthritis [118][119][120][121] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Core molecular mechanisms of programmed cell death in OA. The apoptosis can be induced by caspase-9, caspase-3, TRAIL, and the increase in the BAX/Bcl-2. Pyroptosis is mainly induced by the NLRP3 inflammasome. The NLRP3 inflammasome can activate GSDMD or induce the production of IL-1β and IL-18 to induce pyroptosis. The DAMP, TNF, and complex IIb can induce necroptosis by activating the MLKL. Curprotosis can be induced by the accumulation of copper ions, which can affect the TCA cycle to produce more protein-toxic stress. The over-accumulation of iron can induce ferroptosis by overproduction of ROS, and ferroptosis can lead to the expression of MMP-13 and inhibit the expression of collagen II. The AMPK can inhibit the activation of mTORC1, which can inhibit autophagy or phosphorylation of the ULK1, creating a phosphorylated AMBRA1 to induce autophagy. This figure has been created at https://app.biorender.com (accessed on 21 January 2023).

References

- Das, S.K.; Farooqi, A. Osteoarthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2008, 22, 657–675.

- Reynard, L.N.; Loughlin, J. Genetics and epigenetics of osteoarthritis. Maturitas 2012, 71, 200–204.

- Buckwalter, J.A.; Mankin, H.J. Articular cartilage: Degeneration and osteoarthritis, repair, regeneration, and transplantation. Instr. Course Lect. 1998, 47, 487–504.

- Abramoff, B.; Caldera, F.E. Osteoarthritis: Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 104, 293–311.

- Felson, D.T. Developments in the clinical understanding of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, 203.

- Musumeci, G.; Aiello, F.C.; Szychlinska, M.A.; Di Rosa, M.; Castrogiovanni, P.; Mobasheri, A. Osteoarthritis in the XXIst century: Risk factors and behaviours that influence disease onset and progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 6093–6112.

- Pereira, D.; Ramos, E.; Branco, J. Osteoarthritis. Acta Med. Port. 2015, 28, 99–106.

- Sellam, J.; Berenbaum, F. Is osteoarthritis a metabolic disease? Jt. Bone Spine 2013, 80, 568–573.

- Felson, D.T.; Zhang, Y.; Hannan, M.T.; Naimark, A.; Weissman, B.N.; Aliabadi, P.; Levy, D. The incidence and natural history of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38, 1500–1505.

- Moujalled, D.; Strasser, A.; Liddell, J.R. Molecular mechanisms of cell death in neurological diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 2029–2044.

- Jorgensen, I.; Miao, E.A. Pyroptotic cell death defends against intracellular pathogens. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 265, 130–142.

- D’Arcy, M.S. Cell death: A review of the major forms of apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Cell Biol. Int. 2019, 43, 582–592.

- Hwang, H.S.; Kim, H.A. Chondrocyte Apoptosis in the Pathogenesis of Osteoarthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 26035–26054.

- Yu, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, N.; Tang, L.; Peng, C.; Chen, X. Pyroptosis: Mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 128.

- Yang, J.; Hu, S.; Bian, Y.; Yao, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, X.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, S.; Peng, L. Targeting Cell Death: Pyroptosis, Ferroptosis, Apoptosis and Necroptosis in Osteoarthritis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 789948.

- Mou, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; He, D.; Zhang, C.; Duan, C.; Li, B. Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death: Opportunities and challenges in cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 34.

- Yagoda, N.; Von Rechenberg, M.; Zaganjor, E.; Bauer, A.J.; Yang, W.S.; Fridman, D.J.; Wolpaw, A.J.; Smukste, I.; Peltier, J.M.; Boniface, J.J.; et al. RAS-RAF-MEK-dependent oxidative cell death involving voltage-dependent anion channels. Nature 2007, 447, 864–868.

- Yu, H.; Guo, P.; Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G. Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death, and its relationships with tumourous diseases. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 648–657.

- Latunde-Dada, G.O. Ferroptosis: Role of lipid peroxidation, iron and ferritinophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1893–1900.

- Cao, J.Y.; Dixon, S.J. Mechanisms of ferroptosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 2195–2209.

- Xie, Y.; Hou, W.; Song, X.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Ferroptosis: Process and function. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 369–379.

- Yao, X.; Sun, K.; Yu, S.; Luo, J.; Guo, J.; Lin, J.; Wang, G.; Guo, Z.; Ye, Y.; Guo, F. Chondrocyte ferroptosis contribute to the progression of osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Transl. 2021, 27, 33–43.

- Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Chan, F.K.; Kroemer, G. Necroptosis: Mechanisms and Relevance to Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2017, 12, 103–130.

- Glick, D.; Barth, S.; Macleod, K.F. Autophagy: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Pathol. 2010, 221, 3–12.

- Yin, X.M.; Ding, W.X.; Gao, W. Autophagy in the liver. Hepatology 2008, 47, 1773–1785.

- Mizushima, N. Autophagy: Process and function. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 2861–2873.

- Jing, K.; Lim, K. Why is autophagy important in human diseases? Exp. Mol. Med. 2012, 44, 69–72.

- Ma, Y.; Galluzzi, L.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Autophagy and cellular immune responses. Immunity 2013, 39, 211–227.

- Füllgrabe, J.; Klionsky, D.J.; Joseph, B. The return of the nucleus: Transcriptional and epigenetic control of autophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 65–74.

- Michael, J.W.; Schlüter-Brust, K.U.; Eysel, P. The epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2010, 107, 152–162.

- Kerr, J.F.; Wyllie, A.; Currie, A. Apoptosis: A basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer 1972, 26, 239–257.

- Sharif, M.; Whitehouse, A.; Sharman, P.; Perry, M.; Adams, M. Increased apoptosis in human osteoarthritic cartilage corresponds to reduced cell density and expression of caspase-3. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50, 507–515.

- Hashimoto, S.; Ochs, R.L.; Komiya, S.; Lotz, M. Linkage of chondrocyte apoptosis and cartilage degradation in human osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 41, 1632–1638.

- Pelletier, J.P.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; Abramson, S.B. Osteoarthritis, an inflammatory disease: Potential implication for the selection of new therapeutic targets. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44, 1237–1247.

- Abramson, S.B.; Attur, M.; Yazici, Y. Prospects for disease modification in osteoarthritis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 2006, 2, 304–312.

- Mao, X.; Fu, P.; Wang, L.; Xiang, C. Mitochondria: Potential Targets for Osteoarthritis. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 581402.

- Lepetsos, P.; Papavassiliou, A.G. ROS/oxidative stress signaling in osteoarthritis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 576–591.

- Kapoor, M.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; Lajeunesse, D.; Pelletier, J.P.; Fahmi, H. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2011, 7, 33–42.

- Amin, A.R.; Di Cesare, P.E.; Vyas, P.; Attur, M.; Tzeng, E.; Billiar, T.R.; Stuchin, S.A.; Abramson, S.B. The expression and regulation of nitric oxide synthase in human osteoarthritis-affected chondrocytes: Evidence for up-regulated neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J. Exp. Med. 1995, 182, 2097–2102.

- Loeser, R.F.; Carlson, C.S.; Del Carlo, M.; Cole, A. Detection of nitrotyrosine in aging and osteoarthritic cartilage: Correlation of oxidative damage with the presence of interleukin-1beta and with chondrocyte resistance to insulin-like growth factor 1. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46, 2349–2357.

- Wu, G.J.; Chen, T.G.; Chang, H.C.; Chiu, W.T.; Chang, C.C.; Chen, R.M. Nitric oxide from both exogenous and endogenous sources activates mitochondria-dependent events and induces insults to human chondrocytes. J. Cell. Biochem. 2007, 101, 1520–1531.

- Maneiro, E.; López-Armada, M.J.; De Andres, M.C.; Caramés, B.; Martín, M.A.; Bonilla, A.; Del Hoyo, P.; Galdo, F.; Arenas, J.; Blanco, F.J. Effect of nitric oxide on mitochondrial respiratory activity of human articular chondrocytes. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64, 388–395.

- Ren, H.; Yang, H.; Xie, M.; Wen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, H.; Tang, W.; Wang, M. Chondrocyte apoptosis in rat mandibular condyles induced by dental occlusion due to mitochondrial damage caused by nitric oxide. Arch. Oral Biol. 2019, 101, 108–121.

- Mansfield, K.; Rajpurohit, R.; Shapiro, I.M. Extracellular phosphate ions cause apoptosis of terminally differentiated epiphyseal chondrocytes. J. Cell. Physiol. 1999, 179, 276–286.

- Antoniel, M.; Giorgio, V.; Fogolari, F.; Glick, G.D.; Bernardi, P.; Lippe, G. The oligomycin-sensitivity conferring protein of mitochondrial ATP synthase: Emerging new roles in mitochondrial pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 7513–7536.

- Bauer, T.M.; Murphy, E. Role of Mitochondrial Calcium and the Permeability Transition Pore in Regulating Cell Death. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 280–293.

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 909–950.

- Wenz, T. PGC-1alpha activation as a therapeutic approach in mitochondrial disease. IUBMB Life 2009, 61, 1051–1062.

- Liang, S.; Sun, K.; Wang, Y.; Dong, S.; Wang, C.; Liu, L.; Wu, Y. Role of Cyt-C/caspases-9,3, Bax/Bcl-2 and the FAS death receptor pathway in apoptosis induced by zinc oxide nanoparticles in human aortic endothelial cells and the protective effect by alpha-lipoic acid. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016, 258, 40–51.

- Akhmedov, A.T.; Marín-García, J. Mitochondrial DNA maintenance: An appraisal. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 409, 283–305.

- McCulloch, K.; Litherland, G.J.; Rai, T.S. Cellular senescence in osteoarthritis pathology. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 210–218.

- Grishko, V.I.; Ho, R.; Wilson, G.L.; Pearsall, A.W.t. Diminished mitochondrial DNA integrity and repair capacity in OA chondrocytes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2009, 17, 107–113.

- Blanco, F.J.; López-Armada, M.J.; Maneiro, E. Mitochondrial dysfunction in osteoarthritis. Mitochondrion 2004, 4, 715–728.

- Schuerwegh, A.J.; Dombrecht, E.J.; Stevens, W.J.; Van Offel, J.F.; Bridts, C.H.; De Clerck, L.S. Influence of pro-inflammatory (IL-1 alpha, IL-6, TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma) and anti-inflammatory (IL-4) cytokines on chondrocyte function. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2003, 11, 681–687.

- Kühn, K.; Hashimoto, S.; Lotz, M. IL-1 beta protects human chondrocytes from CD95-induced apoptosis. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 2233–2239.

- Blanco, F.J.; Ochs, R.L.; Schwarz, H.; Lotz, M. Chondrocyte apoptosis induced by nitric oxide. Am. J. Pathol. 1995, 146, 75–85.

- Guo, Q.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Zheng, G.; Xie, C.; Wu, H.; Miao, Z.; Lin, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, W.; et al. STING promotes senescence, apoptosis, and extracellular matrix degradation in osteoarthritis via the NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 13.

- Pistritto, G.; Trisciuoglio, D.; Ceci, C.; Garufi, A.; D’Orazi, G. Apoptosis as anticancer mechanism: Function and dysfunction of its modulators and targeted therapeutic strategies. Aging 2016, 8, 603–619.

- Lee, S.W.; Lee, H.J.; Chung, W.T.; Choi, S.M.; Rhyu, S.H.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, K.T.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.M.; Yoo, Y.H. TRAIL induces apoptosis of chondrocytes and influences the pathogenesis of experimentally induced rat osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50, 534–542.

- Cheng, S.; Nie, Z.; Cao, J.; Peng, H. Circ_0136474 promotes the progression of osteoarthritis by sponging mir-140-3p and upregulating MECP2. J. Mol. Histol. 2022, 54, 1–12.

- Li, Z.; Yuan, B.; Pei, Z.; Zhang, K.; Ding, Z.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Guan, Z.; Cao, Y. Circ_0136474 and MMP-13 suppressed cell proliferation by competitive binding to miR-127-5p in osteoarthritis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 6554–6564.

- Cai, L.; Huang, N.; Zhang, X.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Ke, Q. Long non-coding RNA plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 and growth arrest specific 5 regulate each other in osteoarthritis to regulate the apoptosis of chondrocytes. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 13680–13688.

- Xu, Y.; Duan, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Shi, L. Long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 00707 regulates chondrocyte apoptosis and proliferation in osteoarthritis by serving as a sponge for microRNA-199-3p. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 11137–11145.

- Yuan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, C.; Liu, C.; Xie, J.; Yi, C. Circular RNA circZNF652 is overexpressed in osteoarthritis and positively regulates LPS-induced apoptosis of chondrocytes by upregulating PTEN. Autoimmunity 2021, 54, 415–421.

- Zhou, J.L.; Deng, S.; Fang, H.S.; Du, X.J.; Peng, H.; Hu, Q.J. Circular RNA circANKRD36 regulates Casz1 by targeting miR-599 to prevent osteoarthritis chondrocyte apoptosis and inflammation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 120–131.

- Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Ma, B. Long noncoding RNA NAV2-AS5 relieves chondrocyte inflammation by targeting miR-8082/TNIP2 in osteoarthritis. Cell Cycle 2022, 2022, 1–12.

- Yu, Z.; Cong, F.; Zhang, W.; Song, T.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, R. Circular RNA circ_0020014 contributes to osteoarthritis progression via miR-613/ADAMTS5 axis. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2022, 22, 716–727.

- Bach, D.H.; Lee, S.K.; Sood, A.K. Circular RNAs in Cancer. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2019, 16, 118–129.

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, W.; Li, D.; Zheng, J. miR-146a-5p Promotes Chondrocyte Apoptosis and Inhibits Autophagy of Osteoarthritis by Targeting NUMB. Cartilage 2021, 13 (Suppl. S2), 1467s–1477s.

- Yamasaki, K.; Nakasa, T.; Miyaki, S.; Ishikawa, M.; Deie, M.; Adachi, N.; Yasunaga, Y.; Asahara, H.; Ochi, M. Expression of MicroRNA-146a in osteoarthritis cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 1035–1041.

- Jin, L.; Zhao, J.; Jing, W.; Yan, S.; Wang, X.; Xiao, C.; Ma, B. Role of miR-146a in human chondrocyte apoptosis in response to mechanical pressure injury in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 34, 451–463.

- Shi, J.; Gao, W.; Shao, F. Pyroptosis: Gasdermin-Mediated Programmed Necrotic Cell Death. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 42, 245–254.

- Zhaolin, Z.; Guohua, L.; Shiyuan, W.; Zuo, W. Role of pyroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Cell Prolif. 2019, 52, e12563.

- Lacey, C.A.; Mitchell, W.J.; Dadelahi, A.S.; Skyberg, J.A. Caspase-1 and Caspase-11 Mediate Pyroptosis, Inflammation, and Control of Brucella Joint Infection. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, e00361-18.

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 477–489.

- An, S.; Hu, H.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y. Pyroptosis Plays a Role in Osteoarthritis. Aging Dis. 2020, 11, 1146–1157.

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Chen, D.; He, Y. CY-09 attenuates the progression of osteoarthritis via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 553, 119–125.

- Franceschini, A.; Capece, M.; Chiozzi, P.; Falzoni, S.; Sanz, J.M.; Sarti, A.C.; Bonora, M.; Pinton, P.; Di Virgilio, F. The P2X7 receptor directly interacts with the NLRP3 inflammasome scaffold protein. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 2450–2461.

- Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; Bai, L. The P2X7 Receptor in Osteoarthritis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 628330.

- Mapp, P.I.; Walsh, D.A. Mechanisms and targets of angiogenesis and nerve growth in osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2012, 8, 390–398.

- Degterev, A.; Huang, Z.; Boyce, M.; Li, Y.; Jagtap, P.; Mizushima, N.; Cuny, G.D.; Mitchison, T.J.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Yuan, J. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005, 1, 112–119.

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, R.; Wang, X.; Bao, X.; Lu, C. Roles of necroptosis in alcoholic liver disease and hepatic pathogenesis. Cell Prolif. 2022, 55, e13193.

- Roberts, J.Z.; Crawford, N.; Longley, D.B. The role of Ubiquitination in Apoptosis and Necroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 272–284.

- Pasparakis, M.; Vandenabeele, P. Necroptosis and its role in inflammation. Nature 2015, 517, 311–320.

- Jeon, J.; Noh, H.J.; Lee, H.; Park, H.H.; Ha, Y.J.; Park, S.H.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.J.; Kang, H.C.; Eyun, S.I.; et al. TRIM24-RIP3 axis perturbation accelerates osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 1635–1643.

- Sokolove, J.; Lepus, C.M. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: Latest findings and interpretations. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet Dis. 2013, 5, 77–94.

- Riegger, J.; Brenner, R.E. Evidence of necroptosis in osteoarthritic disease: Investigation of blunt mechanical impact as possible trigger in regulated necrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 683.

- Gong, Y.; Qiu, J.; Ye, J. AZ-628 delays osteoarthritis progression via inhibiting the TNF-α-induced chondrocyte necroptosis and regulating osteoclast formation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 111, 109085.

- Li, B.; Guan, G.; Mei, L.; Jiao, K.; Li, H. Pathological mechanism of chondrocytes and the surrounding environment during osteoarthritis of temporomandibular joint. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 4902–4911.

- Lawlor, K.E.; Khan, N.; Mildenhall, A.; Gerlic, M.; Croker, B.A.; D’Cruz, A.A.; Hall, C.; Kaur Spall, S.; Anderton, H.; Masters, S.L.; et al. RIPK3 promotes cell death and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the absence of MLKL. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6282.

- Dannappel, M.; Vlantis, K.; Kumari, S.; Polykratis, A.; Kim, C.; Wachsmuth, L.; Eftychi, C.; Lin, J.; Corona, T.; Hermance, N.; et al. RIPK1 maintains epithelial homeostasis by inhibiting apoptosis and necroptosis. Nature 2014, 513, 90–94.

- Cheng, J.; Duan, X.; Fu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, P.; Cao, C.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. RIP1 Perturbation Induces Chondrocyte Necroptosis and Promotes Osteoarthritis Pathogenesis via Targeting BMP7. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 638382.

- Martens, S.; Hofmans, S.; Declercq, W.; Augustyns, K.; Vandenabeele, P. Inhibitors Targeting RIPK1/RIPK3: Old and New Drugs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41, 209–224.

- Tong, L.; Yu, H.; Huang, X.; Shen, J.; Xiao, G.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Xing, L.; Chen, D. Current understanding of osteoarthritis pathogenesis and relevant new approaches. Bone Res. 2022, 10, 60.

- Yang, W.S.; SriRamaratnam, R.; Welsch, M.E.; Shimada, K.; Skouta, R.; Viswanathan, V.S.; Cheah, J.H.; Clemons, P.A.; Shamji, A.F.; Clish, C.B.; et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell 2014, 156, 317–331.

- Miao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xue, F.; Liu, K.; Zhu, B.; Gao, J.; Yin, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, G. Contribution of ferroptosis and GPX4’s dual functions to osteoarthritis progression. EBioMedicine 2022, 76, 103847.

- Yan, H.F.; Zou, T.; Tuo, Q.Z.; Xu, S.; Li, H.; Belaidi, A.A.; Lei, P. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 49.

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 266–282.

- Mehana, E.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; El-Blehi, S.S. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in osteoarthritis pathogenesis: An updated review. Life Sci. 2019, 234, 116786.

- Kim, Y.C.; Guan, K.L. mTOR: A pharmacologic target for autophagy regulation. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 25–32.

- Valenti, M.T.; Dalle Carbonare, L.; Zipeto, D.; Mottes, M. Control of the Autophagy Pathway in Osteoarthritis: Key Regulators, Therapeutic Targets and Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2700.

- Luo, P.; Gao, F.; Niu, D.; Sun, X.; Song, Q.; Guo, C.; Liang, Y.; Sun, W. The Role of Autophagy in Chondrocyte Metabolism and Osteoarthritis: A Comprehensive Research Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 5171602.

- Pal, B.; Endisha, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kapoor, M. mTOR: A potential therapeutic target in osteoarthritis? Drugs RD 2015, 15, 27–36.

- Feng, X.; Pan, J.; Li, J.; Zeng, C.; Qi, W.; Shao, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Xiao, G.; Zhang, H.; et al. Metformin attenuates cartilage degeneration in an experimental osteoarthritis model by regulating AMPK/mTOR. Aging 2020, 12, 1087–1103.

- Collins, J.A.; Diekman, B.O.; Loeser, R.F. Targeting aging for disease modification in osteoarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2018, 30, 101–107.

- Wang, S.; Deng, Z.; Ma, Y.; Jin, J.; Qi, F.; Li, S.; Liu, C.; Lyu, F.J.; Zheng, Q. The Role of Autophagy and Mitophagy in Bone Metabolic Disorders. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 2675–2691.

- Duan, R.; Xie, H.; Liu, Z.Z. The Role of Autophagy in Osteoarthritis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 608388.

- Kahlson, M.A.; Dixon, S.J. Copper-induced cell death. Science 2022, 375, 1231–1232.

- Li, S.R.; Bu, L.L.; Cai, L. Cuproptosis: Lipoylated TCA cycle proteins-mediated novel cell death pathway. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 158.

- Cobine, P.A.; Brady, D.C. Cuproptosis: Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying copper-induced cell death. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 1786–1787.

- Tsvetkov, P.; Coy, S.; Petrova, B.; Dreishpoon, M.; Verma, A.; Abdusamad, M.; Rossen, J.; Joesch-Cohen, L.; Humeidi, R.; Spangler, R.D.; et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science 2022, 375, 1254–1261.

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, G.; Yan, W.; Zhan, H.; Sun, P. miR-146b-5p regulates cell growth, invasion, and metabolism by targeting PDHB in colorectal cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017, 7, 1136–1150.

- Saunier, E.; Benelli, C.; Bortoli, S. The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in cancer: An old metabolic gatekeeper regulated by new pathways and pharmacological agents. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 809–817.

- Smolle, M.; Lindsay, J.G. Molecular architecture of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex: Bridging the gap. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006, 34, 815–818.

- Park, S.; Baek, I.J.; Ryu, J.H.; Chun, C.H.; Jin, E.J. PPARα-ACOT12 axis is responsible for maintaining cartilage homeostasis through modulating de novo lipogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3.

- Mayr, J.A.; Feichtinger, R.G.; Tort, F.; Ribes, A.; Sperl, W. Lipoic acid biosynthesis defects. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2014, 37, 553–563.

- Frommer, K.W.; Hasseli, R.; Schäffler, A.; Lange, U.; Rehart, S.; Steinmeyer, J.; Rickert, M.; Sarter, K.; Zaiss, M.M.; Culmsee, C.; et al. Free Fatty Acids in Bone Pathophysiology of Rheumatic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2757.

- Guo, W.; Wei, B.; Sun, J.; Chen, T.; Wei, J.; Hu, Z.; Chen, S.; Xiang, M.; Shu, Y.; Peng, Z. Suppressive oligodeoxynucleotide-induced dendritic cells rein the aggravation of osteoarthritis in mice. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2018, 40, 430–436.

- Farinelli, L.; Aquili, A.; Mattioli-Belmonte, M.; Manzotti, S.; D’Angelo, F.; Ciccullo, C.; Gigante, A. Synovial mast cells from knee and hip osteoarthritis: Histological study and clinical correlations. J. Exp. Orthop. 2022, 9, 13.

- Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Brunner, T.M.; Hu, X.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, L.; Wu, P.; Li, M.; Liu, Q.; et al. Menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells efficiently ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting T cell activation in mice. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 155.

- Wang, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Yu, L.; Sun, Z. Chemokine (C-C Motif) Ligand 2/Chemokine Receptor 2 (CCR2) Axis Blockade to Delay Chondrocyte Hypertrophy as a Therapeutic Strategy for Osteoarthritis. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2021, 27, e930053.

More