Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Freya Hammar.

The mtDNA of the myxomycete Physarum polycephalum can contain as many as 81 genes. These genes can be grouped in three different categories. The first category includes 46 genes that are classically found on the mtDNA of many organisms. A second category of gene is putative protein-coding genes represented by 26 significant open reading frames. The third category of gene is found in the mtDNA of some strains of P. polycephalum. These genes derive from a linear mitochondrial plasmid with nine significant, but unassigned, open reading frames which can integrate into the mitochondrial DNA by recombination.

- myxomycetes

- mitochondrial DNA

- RNA editing

- cryptogenes

1. Introduction

Mitochondrial DNA Evolution

Although most of the genes of eukaryotic organisms are located on nuclear chromosomes, a small number of genes are located on the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in mitochondria. These genes are necessary for mitochondrial function and biogenesis. They include genes that encode mRNAs for protein subunits of complexes of the ETC (electron transport chain) and mitochondrial ATP synthase involved in the OXPHOS (oxidative phosphorylation) pathway. In addition, some of the genes encode tRNAs and rRNAs necessary for mitochondrial protein synthesis and often genes encoding mRNAs for protein subunits for the mitochondrial ribosomes [1].

It is nearly universally accepted that mitochondria derive from a single endosymbiotic event in which a eubacterium was taken up by either a proto-eukaryote [2] or an archaebacterium [1]. The eubacterium is widely accepted to have been of the class α-proteobacterium and order Rickettsiales based on the sequence similarity and gene organization between Rickettsia and the mtDNA of certain protists, exemplified by Reclinomonas americana [1]. The gene content and size of the protomitochondrial genome is difficult to predict since contemporary mtDNAs vary extensively in size, structure, and gene content [3,4,5,6,7][3][4][5][6][7]. Gene reduction has been a universal result of mtDNA evolution, although the extent of gene loss varies widely among the mtDNAs of animals [5], plants [6], fungi, and protists [7]. Even the number of protein-coding genes in the mtDNA of R. americana (69 genes) is greatly reduced relative to Rickettsia (834 protein-coding genes), indicating a tendency of gene reduction due to gene loss or to transfer of mitochondrial genes to the nucleus known as endosymbiotic gene transfer (EGT) [1].

2. The Mitochondrial DNA of P. polycephalum

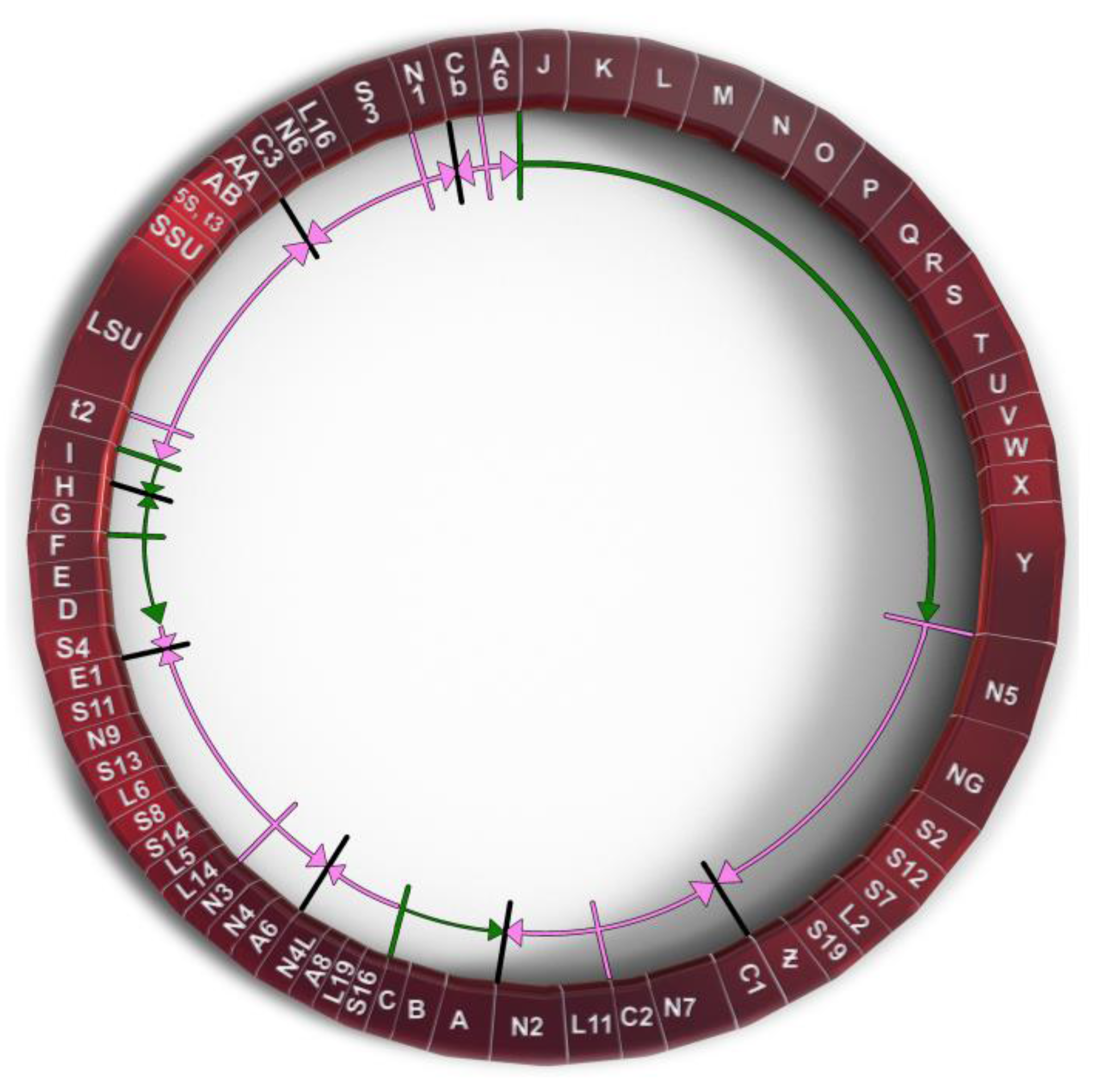

P. polycephalum is a myxomycete or acellular slime mold and is a eukaryote belonging to a clade whose ancestor diverged early from those of plants, animals, and fungi. The most common mtDNA structure in strains of P. polycephalum is circular and contains 72 genes (Figure 1). The mtDNA varies in size from 56 to 62 kb, depending on the presence of some small deletions in the mtDNA of some strains [8], reviewed in [9]. This mtDNA is unique in that it is composed of two different types of gene. The first type includes 46 genes which are homologous to genes found on the mtDNA of R. americana and together account for 38.5 kb of the mtDNA (red arrows in Figure 1), indicating that they are derived from the common eubacterial ancestor. A second type of potential gene includes 26 significant open reading frames located on 24.3 kb of the mtDNA (green arrows in Figure 1). The 26 unassigned open reading frames are interspersed with the classical, ancestral genes at four positions (group 1, URFs A, B, C; group 2, URFs D–I; group 3, URFs J–Y; group 4, URF Z; Figure 1). Only one ORF (URF Z) is transcribed, the other 25 URFs are not transcribed [10,11][10][11].

Figure 1. Genetic map of P. polycephalum’s mtDNA showing its 72 genes. Gene symbols are as defined in Table 1. Genes which have their direction of potential transcription marked by green arrows are unassigned reading frames. Genes marked with pink arrows show the direction of transcription for classic mitochondrial genes.

2.1. Mitochondrial Insertional Cotranscriptional RNA Editing in the Myxomycetes (MICOTREM)

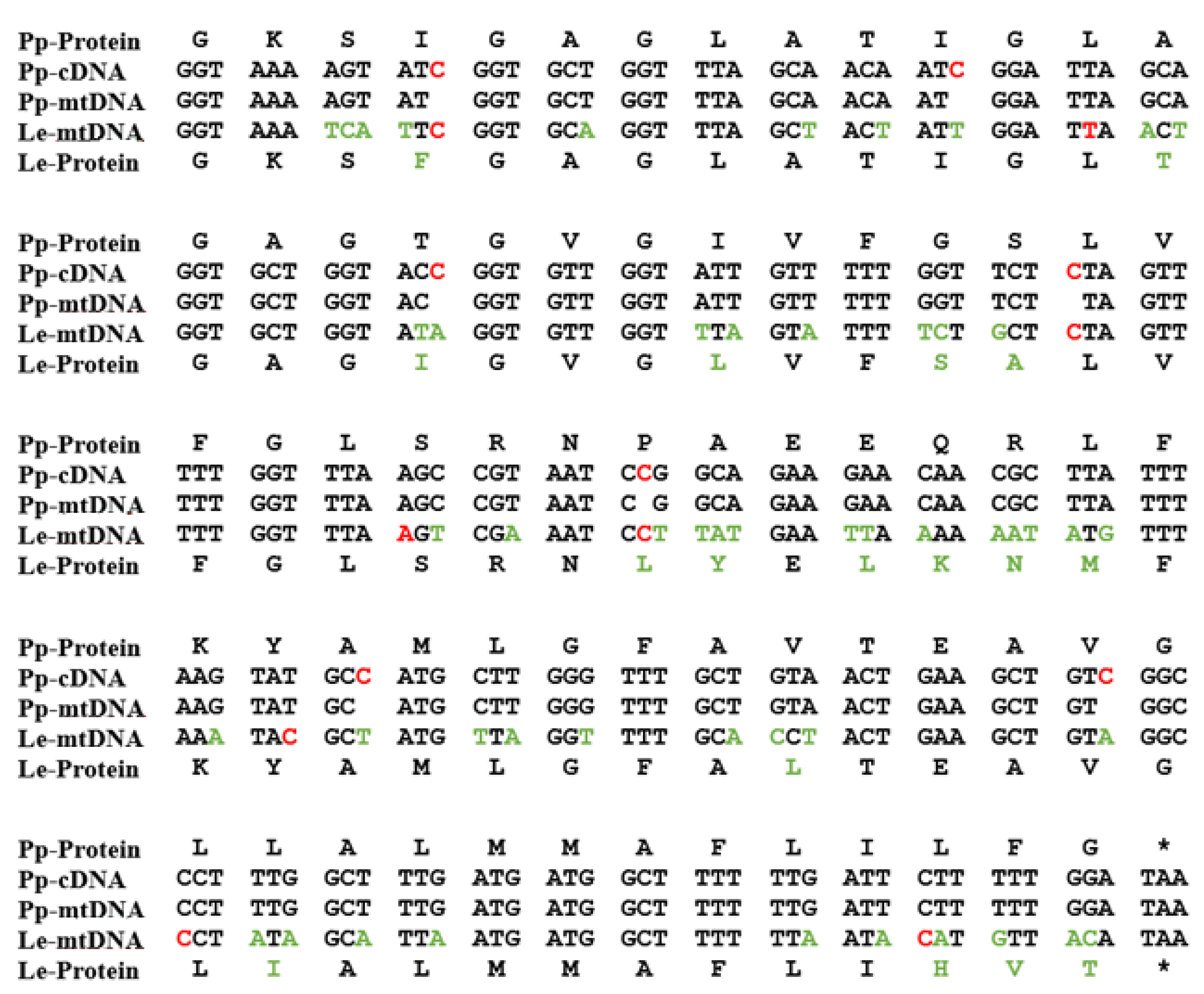

Probably the most unique derived characteristic of the P. polycephalum mtDNA is the RNA editing needed to express 43 of the 47 transcribed genes (recently reviewed in [9] and [12]). This unique type of RNA editing was first identified and characterized by Mahendran et al. [13] in the α subunit of the ATP synthase cryptogene (genes requiring RNA editing to provide genetic information necessary for their expression) in the mtDNA of P. polycephalum and later extended to additional cryptogenes in the P. polycephalum mtDNA [14,15,16,17,18,19][14][15][16][17][18][19]. This unique type of RNA editing has been designated MICOTREM (Mitochondrial Insertional, Cotranscriptional RNA Editing in Myxomycetes). Currently, MICOTREM has only been found in the mtDNAs of the myxomycetes [20] and produces genetic information lacking in the cryptogenes by inserting nucleotides in RNA relative to the template DNA to create open reading frames in mRNAs and functional RNA structure in tRNAs and rRNAs. These non-templated nucleotide insertions are most commonly single cytidines but can also be single uridines or a subset of the possible dinucleotides (CU or UC, AA, GC or CG, UU, UA). These non-templated insertions are separated by an average of about 25 nucleotides in mRNAs, so that about 4% of the mRNA nucleotides are non-templated. Although the distribution of editing sites appears essentially random, no two insertion sites have been observed closer than nine nucleotides (Figure 2). Overall, 1324 RNA editing sites have been identified in the RNAs produced from the classical, ancestral genes of P. polycephalum, 1301 single-nucleotide sites and 23 dinucleotide sites for a total of 1347 non-templated nucleotides added to mitochondrial RNAs [11].

Figure 2. A portion of the atp9 gene on the mtDNA of P. polycephalum (Pp-mtDNA) and Lycogala epidendrum (Le-mtDNA) aligned with P. polycephalum cDNA (Pp-cDNA) and the inferred protein products using the classic genetic code. The alignment shows the editing site distribution and variation in editing site locations in different myxomycetes. Red letters in Pp-cDNA are experimentally determined RNA editing sites in P. polycephalum. Red letters in Le-mtDNA are RNA editing sites inferred by alignment. Green letters in Le-mtDNA and Le-Protein show differences between the P. polycephalum and L. epidendrum sequences. * indicates termination codon.

Evolution of RNA Editing Site Location

Comparison of RNA editing sites within the same genes of different myxomycetes shows that while they all display MICOTREM editing, the location of RNA editing sites varies relative to conserved regions within analogous genes (Figure 2). In contrast to the conservation of editing sites in the mtDNA of individual myxomycetes, this observation implies an unanticipated dynamic in the location of editing sites over evolutionary time periods and provides insight into the constraints on editing site location and distribution, as well as the mechanism of editing site fixation and elimination. Krishnan et al. [20] compared editing site location in a 452-nucleotide region of the small subunit rRNA among six myxomycetes. Each myxomycete had a similar number of editing sites (eight to ten) which were distributed such that no two editing sites were closer than nine nucleotides and, in each case, restored the conserved sequence of the SSU rRNA. However, these editing sites were distributed in different patterns in the six different RNAs and were located at 29 different sites relative to the conserved sequence of the RNA. In general, the more closely related the myxomycetes, the more editing sites they have at the same location. These variations indicate that editing sites can be created and/or removed over evolutionary time. Analysis of these editing patterns in relationship to established phylogenetic trees confirm that editing sites have been both created and deleted during the evolution of the mtDNA to produce the editing patterns observed in contemporary organisms. Editing site patterns may also be altered by the removal of RNA editing sites. Landweber [27][25] and Simpson and colleagues [28,29][26][27] have proposed retrotranscription as a mechanism of eliminating insertional editing sites. Integration of cDNAs produced from reverse transcription of edited RNAs would remove the deletions in the mtDNA and eliminate the need for a compensating insertion of nucleotides in the RNA.2.2. Unidentified, Untranscribed but Significant Open Reading Frames in the mtDNA of P. polycephalum

A second unique feature of P. polycephalum mtDNA is the presence of 26 open readings that do not correspond to any of the genes classically observed on mitochondrial DNAs [8,9][8][9]. Most of these reading frames are significantly long (greater than 100 codons), so that they are not likely to have been generated by chance, but with one exception are not transcribed [10,11][10][11] The fact that these significant unassigned reading frames (SURFs) remain intact in the absence of the transcription that would provide the selection to maintain open reading frames, implies that they may be recently acquired. The 26 SURFs are interspersed within the classical genes of the mtDNA in four groups. Group 1 SURFs are designed A, B, and C and would be transcribed counterclockwise in Figure 1 in the order CBA. URFs A and B would code for proteins of 238 and 411 amino acids, respectively. These proteins have transmembrane characteristics consistent with being membrane proteins. However, they do not have significant homology with any protein in GenBank. URF C, a smaller open reading frame, also does not have significant homology to any gene in GenBank. The Group 2 untranscribed region has six SURFs, two that would be transcribed clockwise in Figure 1 (G and H), and four which would be transcribed counterclockwise in Figure 1 (I, F, E, D). SURFs D, E, H, and I have transmembrane characteristics but none of these SURFs have significant similarity to proteins in GenBank. The largest group of SURFs is Group 3 which includes SURFs J to Y and covers 18,022 base pairs of the mtDNA. These 16 SURFs would all be transcribed clockwise in Figure 1 and have very little noncoding space between reading frames. These SURFs are predicted to code for proteins ranging in size from 112 amino acids (SURF V) to 724 amino acids (URF Y). SURFs J, K, L, N, O, Q, S, T, and U would code for proteins predicted to have transmembrane features and could be membrane proteins. Most of these SURFs would code for proteins that do not have similarity to any proteins in GenBank; however, several of the proteins predicted to be produced from these SURFs have recently been matched with proteins. SURF N (400 amino acids) and SURF Q (389 amino acids) have similarity to each other and to a hypothetical protein from Flavobacteriales bacterium (328 amino acids, GenBank sequence ID: NQX98395.1) recently identified during a metagenomic search of ocean water from the marine abyssalpelagic zone, Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Gyre, Station ALOHA (Leu, A. O., 2020, unpublished). All three hypothetical proteins have a region of similarity of about 200 amino acids starting at 139 amino acids from the N-terminus. SURF R (663 nucleotides, 221 amino acids) has a region of identity to SURF 7 (1098 nucleotides, 366 amino acids) in the mitochondrial mF plasmid (see below). This region of identity in SURF R is 474 nucleotides (158 amino acids) in length starting near the N-terminus. This region of identity is the site of homologous recombination between the circular P. polycephalum mtDNA and the mF plasmid (see below). The one SURF with the potential to produce a protein with a known function is SURF Y. SURF Y has the potential to produce a protein 724 amino acids in length. This protein has significant homology to a number of single subunit RNA polymerases from linear mitochondrial plasmids. This RNA polymerase is presumably not the mitochondrial RNA polymerase used to transcribe genes on the mtDNA of P. polycephalum, since this SURF is not transcribed, and the encoded RNA polymerase is not produced. (The actual RNA polymerase used to transcribe the mtDNA is encoded in the nucleus and is well characterized [24][21].) The similarity of the SURF Y amino acid sequence to RNA polymerases on linear mitochondrial plasmids and the identity of the portion of SURF R with SURF 7 of the mF linear mitochondrial plasmid argues that this region of the mtDNA may derive from a linear mitochondrial plasmid or a related bacteriophage with a linear double stranded DNA such as phi 29 [30][28]. Group 4 consists of one SURF, ORF Z. In contrast to the other unassigned reading frames, ORF Z is transcribed and in a clockwise direction. It is possible that this unidentified ORF is a classical mitochondrial gene but has diverged to an extent that it cannot be identified. However, the absence of MICOTREM RNA editing argues against it being classical and argues for it being recently acquired.References

- Gray, M.W.; Burger, G.; Lang, B.F. Mitochondrial Evolution. Science 1999, 283, 1476–1482.

- Thorsness, P.E.; Hanekamp, T. Mitochondria: Origin; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2001.

- Kolesnikov, A.A.; Gerasimov, E.S. Diversity of mitochondrial genome organization. Biochemistry 2012, 77, 1424–1435.

- Smith, D.R.; Keeling, P.J. Mitochondrial and plastid genome architecture: Reoccurring themes, but significant differences at the extremes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10177–10184.

- Lavrov, D.V.; Pett, W. Animal mitochondrial DNA as we do not know it: Mt-genome organization and evolution in nonbilaterian lineages. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 2896–2913.

- Gualberto, J.M.; Mileshina, D.; Wallet, C.; Niazi, A.K.; Weber-Lotfi, F.; Dietrich, A. The plant mitochondrial genome: Dynamics and maintenance. Biochimie 2014, 100, 107–120.

- Zikova, A.; Hampl, V.; Paris, Z.; Tyc, J.; Lukes, J. Aerobic mitochondria of parasitic protists: Diverse genomes and complex functions. Mol. Biochem. Parisitol. 2016, 209, 45–57.

- Takano, H.; Abe, T.; Sakurai, R.; Moriyama, Y.; Miyazawa, Y.; Nozaki, H.; Kawano, S.; Sasaki, N.; Kuroiwa, T. The complete DNA sequence of the mitochondrial DNA of P. polycephalum. Mol. Gen. Genet. 2001, 264, 539–545.

- Miller, D.; Padmanabhan, R.; Sarcar, S.N. Genomics and gene expression in myxomycetes. In Myxomycetes: Biology, Systematics, Biogeography and Ecology, 2nd ed.; Rojas, C., Stephenson, S.L., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 153–193.

- Jones, E.P.; Mahendran, R.; Spottswood, M.R.; Yang, Y.-C.; Miller, D.L. Mitochondrial DNA of Physarum: Physical Mapping, Cloning, and Transcription Mapping. Curr. Genet. 1990, 17, 331–337.

- Bundschuh, R.; Antmuller, J.; Becker, C.; Nurnburg, P.; Gott, J.M. Complete characterization of the edited transcriptome of the mitochondrion of Physarum polycephalum using deep sequencing of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 6044–6055.

- Houtz, J.; Cremona, N.; Gott, J.M. Editing of mitochondrial RNAs in P. polycephalum. In RNA Metabolism in Mitochondria; Cruz-Reyes, J., Gray, M.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 199–222.

- Mahendran, R.; Spottswood, M.S.; Miller, D.L. RNA editing by cytidine insertion in mitochondria of P. polycephalum. Nature 1991, 349, 434–438.

- Miller, D.L.; Mahendran, R.; Spottswood, M.S.; Costandy, H.; Ling, M.L.; Yang, N. Insertional editing in mitochondria of Physarum. Semin. Cell Biol. 1993, 4, 261–266.

- Miller, D.L.; Mahendran, R.; Spottswood, M.S.; Ling, M.L.; Wang, S.; Yang, N.; Costandy, H. RNA editing in mitochondria of P. polycephalum. In RNA Editing: The Alteration of Protein Coding Sequences of RNA; Benne, R., Ed.; Ellis Horwood: Chichester, UK, 1993; pp. 87–103.

- Miller, D.L.; Mahendran, R.; Spottswood, M.S.; Ling, M.L.; Wang, S.; Yang, N.; Costandy, H. RNA editing in mitochondria of Physarum polycephalum. In Plant Mitochondria; Brennicke, A., Kuck, U., Eds.; VHC: Weinheim, Germany, 1993; pp. 53–62.

- Gott, J.M.; Visomirski, L.M.; Hunter, J.L. Substitutional and insertional RNA editing of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I mRNA of P. polycephalum. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 25483–25486.

- Mahendran, R.; Spottswood, M.S.; Ghate, A.; Ling, M.L.; Jeng, K.; Miller, D.L. Editing of the mitochondrial small subunit rRNA in P. polycehalum. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 232–240.

- Antes, T.; Costandy, H.; Mahendran, R.; Spottswood, M.; Miller, D. Insertional editing of tRNAs of P. polycephalum and Didymium nigripes. Mol. Cell Biol. 1998, 18, 7521–7527.

- Krishnan, U.; Barsamian, A.; Miller, D.L. Evolution of RNA Editing Sites in the Mitochondrial Small Subunit rRNA of the Myxomycetes. Methods Enzymol. 2007, 424, 197–220.

- Miller, M.L.; Antes, T.J.; Qian, F.; Miller, D.L. Identification of a putative mitochondrial RNA polymerase from P. polycephalum: Characterization, expression, purification, and transcription in vitro. Curr. Genet. 2006, 49, 259–271.

- Rhee, A.C.; Somerlot, B.H.; Parmi, N.; Gott, J.M. Distinct roles for sequences upstream of and downstream from Physarum editing sites. RNA 2009, 15, 1753–1765.

- Miller, M.L.; Miller, D.L. Non-DNA-templated addition of nucleotides to the 3′ end of RNAs by the mitochondrial RNA Polymerase of P. polycephalum. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 28, 5795–5802.

- Sarcar, S.N.; Miller, D.L. A specific, promoter-independent activity of T7 RNA polymerase suggests a general model for DNA/RNA editing in single subunit RNA polymerases. Nat. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13885.

- Landweber, L.F. The evolution of RNA editing in kinetoplastid protozoa. Biosystems 1992, 28, 41–45.

- Maslov, D.A.; Avila, H.A.; Lake, J.A.; Simpson, L. Evolution of RNA editing in kinetoplastid protozoa. Nature 1994, 368, 345–348.

- Simpson, L.; Maslov, D.A. Ancient origin of RNA editing in kinetoplastid protozoa. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1994, 4, 887–894.

- Skaguchi, K. Invertrons, a class of structurally and functionally related genetic elements that includes linear DNA plasmids, Transposable Elements, and genomes of adeno-type viruses. Microbiol. Rev. 1990, 54, 66–74.

More