Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 1 by Jonathan J Kopel.

Obeticholic acid (OCA) or 6-alpha-ethyl-chenodeoxycholic acid is a semisynthetic modified bile acid derivative that acts on the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) as an agonist with a higher potency than bile acid. The FXR is a nuclear receptor highly expressed in the liver and small intestine and regulates bile acid, cholesterol, glucose metabolism, inflammation, and apoptosis.

- obeticholic acid

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- metabolic syndrome

1. Introduction

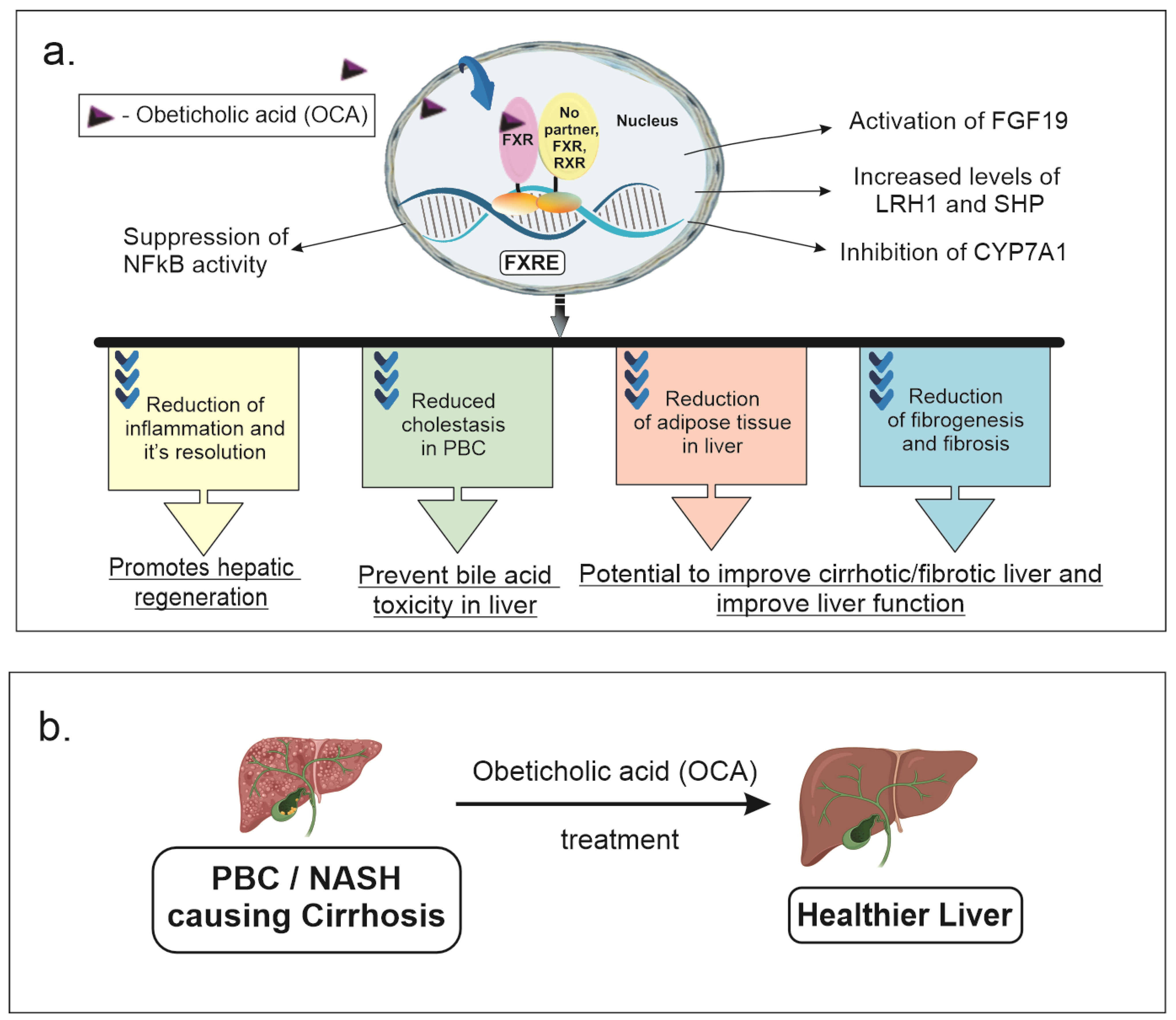

The farnesoid X receptor (FXR) is a nuclear receptor that can form a heterodimer with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) or bind to its gene response element in its monomeric form. The binding to the FXR element (FXRE) can result in differential activation or repression of downstream targets [1,2,3,4,5,6][1][2][3][4][5][6]. The FXR is a nuclear receptor highly expressed in the liver and small intestine, especially the distal ileum, as well as the kidneys, adrenal glands, muscles, adipose tissue, and cardiac muscle, that regulates bile acid, cholesterol, glucose metabolism, inflammation, and apoptosis [1,2,3,4,6,7][1][2][3][4][6][7]. The role of FXR in liver and small intestine has been extensively studied in regulating bile acid, cholesterol, glucose metabolism, inflammation, and apoptosis [8]. In the liver, FXR primarily acts as a bile acid sensor. FXR activation causes release of FGF19, acts as an endocrine signaling molecule from enterocytes to the liver, which causes a decrease in bile acid synthesis and release. LRH1 and SHP levels are increased due to FXR activation, which also decreases bile acid synthesis via inhibition of CYP7A1, cholesterol utilization and fatty acid metabolism. Several animal and clinical studies are underway to target therapies, such as Obeticholic acid (OCA), towards FXR for the treatment of cardiovascular disease, male infertility, kidney failure, obesity, and vascular disease [9,10,11][9][10][11]. Obeticholic acid (OCA) or 6-alpha-ethyl-chenodeoxycholic acid is a semisynthetic modified bile acid (BA) derived from chenodeoxycholic acid that is a potent activator of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) [1,2,3,4,12][1][2][3][4][12]. Figure 1 shows the effects of OCA on physiology and pathology where it crosses the cell membrane in liver and enterocytes to activate FXR that can form a heterodimer with the RXR, homodimer with FXR, or bind to DNA as a monomer.The FXR is a nuclear receptor highly expressed in the liver and small intestine that regulates bile acid, cholesterol, glucose metabolism, inflammation, and apoptosis. Several animal and clinical studies are underway for targeted therapies towards FXR for the treatment of cardiovascular disease, male infertility, kidney failure, obesity, and vascular disease [9,10,11][9][10][11].

Figure 1. OCA effects on physiology and pathology: (a) OCA crosses the cell membrane in liver and enterocytes to activate FXR (FXR) that can form a heterodimer with the retinoid x receptor (RXR), a homodimer with FXR, or bind to DNA as a monomer. This can activate various signaling pathways, decreasing bile acid synthesis, fatty acid and cholesterol metabolism, glucose metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis. FXR activation causes release of fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) which acts as an endocrine signaling molecule released from enterocytes to the liver causing decreased bile acid. Liver related homolog 1 (LRH1) and small heterodimer protein (SHP) levels are increased due to FXR activation, which also decreased bile acid synthesis via inhibition of CYP7A1, cholesterol utilization and fatty acid metabolism. This all improves cholestasis in patients with PBC. In mouse models, anti-inflammatory effects of OCA are mediated via suppression of nuclear factor k activator of B cells (NFkB) signaling. This mediates reduction in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis seen in mouse models of non-alcoholic steato hepatitis (NASH). (b) Improvement in liver functional status after OCA treatment in mouse models of cirrhosis due to NASH or primary biliary cholangitis (PBC).

2. The Effects of OCA on Different Physiological Processes through FXR Activation

2.1. OCA Effect on Bile Acid Synthesis

One of FXR’s main roles is to inhibit bile acid synthesis through regulating the expression of small heterodimer partner (SHP). SHP inactivates liver-related homolog-1 protein (LRH-1), which in turn represses the expression of the cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) enzyme [13]. CYP7A1 is the rate-limiting step in BA synthesis within the liver. Another mechanism by which FXR can downregulate CYP7A1 is via the induction of fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) within enterocytes located in the ileal region. This molecule can act as an endocrine signaling hormone, activating the JNK signaling cascade, and causing a downregulation of CYP7A1 expression after reaching the liver via enterohepatic circulation [14,15][14][15]. Through inhibiting and downregulating CYP7A1, FXR is believed to exert hepatoprotective properties by preventing the accumulation of toxic BA buildup in the liver and promoting hepatic regeneration after liver damage in mouse models [16,17,18][16][17][18]. The primary method by which OCA reduces circulating bile salts is through upregulation of the bile salt exporter pump (BSEP) to increase bile salt excretion into the biliary tree [19,20,21][19][20][21]. In addition, OCA decreases intestinal cholesterol absorption rather than increasing biliary cholesterol production [22]. OCA also inhibits hepatic sterol 12 hydroxylase (CYP8B1) and cholesterol 7 hydroxylase (CYP7A1), in part by inducing a small heterodimer partner [22]. This results in a smaller bile acid pool and a change in the composition of the bile, with an increase in the proportion of α/β-muricholic acid and a decrease in taurocholic acid [22]. Additional studies using primary hepatocytes showed that OCA treatment suppressed bile acid synthesis genes (CYP7A1, CYP27A1) and increased bile efflux genes (ABCB4, ABCB11, OSTA, OSTB) [23,24][23][24].2.2. OCA Effect on Fatty Acid Metabolism

In addition, the FXR plays an important role in fat metabolism, which includes regulating the expression of several lipoproteins, including apolipoprotein E and very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) [25,26,27,28,29,30][25][26][27][28][29][30]. By phosphorylating insulin responsive substrate-1 on serine 312 in the liver and muscles, FXR activation was found to reduce body weight gain, prevent fat from accumulating in the liver and muscles, and reverse insulin resistance [26]. Genes involved in fatty acid production, lipogenesis, and gluconeogenesis had their liver expression decreased by FXR activation. Free fatty acid production in the muscles was also decreased by FXR therapy [26]. A subsequent study using OCA reduced the amount of visceral adipose tissue, steatosis, and other inflammatory markers in rabbits fed a high fat diet [31]. Similar results were also observed in mice, hamsters, and human [32,33,34,35][32][33][34][35].2.3. OCA’s Effect on Vascular and Inflammatory Processes in the Liver

Within vascular smooth muscle cells, OCA can induce smooth muscle cell death and downregulate interleukin (IL)-1β-induced inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 expression [36]. In addition, OCA suppressed smooth muscle cell migration stimulated by platelet-derived growth factor-BB. However, a recent mouse model study suggested that OCA may not help with hepatic regeneration resulting from liver injury [37]. Further studies will need to be done to assess whether OCA may revert liver damage in human patients. The binding of OCA to FXR has also been shown to decrease the expression of nuclear factor κ light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) by inducing expression of cytochrome P450. This process can reduce inflammasome formation and prevent the development of various liver and vascular pathologies [38]. Along with its effects on metabolism, OCA also acts as an anti-inflammatory agent via activation of FXR in liver [36,39,40,41,42,43,44][36][39][40][41][42][43][44]. Several animal studies have shown that loss of FXR or FXR deficiency, results in increased hepatic inflammation and fibrosis [39,40,41,42,45,46][39][40][41][42][45][46]. Specifically, it was found that activation of FXR reduced the production of fibrosis from hepatic stellate cells through altering the activities of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and SHP. In response, there is a corresponding reduction in the pro-fibrotic activities of α1 collagen, TGF-β1, and NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation [43,46][43][46]. Further improvements in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis were also observed when OCA was combined with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists [47]. A similar result was also observed when OCA was combined with an anti-apoptosis inhibitor (IDN-6556), PPAR-α/δ agonists, and statins [48,49,50][48][49][50]. Further studies using primary hepatocytes treated with OCA reduced TGFβ and IL-6 signaling pathways as well as reduced HDL genes (SCARB1, ApoAI, LCAT) while LDL genes (ApoB, CYP7A1) increased [23]. In recent years, the FXR group of bile acid receptors is currently under investigation for its potential role in the treatment of primary biliary colangitis (PBC), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71]. In 2016, the Food and Drug Administration approved OCA for treating PBC refractory to ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) [45]. Besides OCA, several other FXR agonists are under investigation for the treatment of PBC and NASH [72,73,74,75][72][73][74][75]. Recent clinical studies suggest OCA may work synergistically with lipid modifying medications to further improve long-term outcomes with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Specifically, OCA improves morbidity and mortality in NASH patients with their different histological, metabolic, and biochemical issues in PBC, PSC, or liver patients.References

- Pellicciari, R.; Fiorucci, S.; Camaioni, E.; Clerici, C.; Costantino, G.; Maloney, P.R.; Morelli, A.; Parks, D.J.; Willson, T.M. 6alpha-ethyl-chenodeoxycholic acid (6-ECDCA), a potent and selective FXR agonist endowed with anticholestatic activity. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 3569–3572.

- Costantino, G.; Macchiarulo, A.; Entrena-Guadix, A.; Camaioni, E.; Pellicciari, R. Binding mode of 6ECDCA, a potent bile acid agonist of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 1865–1868.

- Claudel, T.; Sturm, E.; Kuipers, F.; Staels, B. The farnesoid X receptor: A novel drug target? Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2004, 13, 1135–1148.

- Chen, J.; Raymond, K. Nuclear receptors, bile-acid detoxification, and cholestasis. Lancet 2006, 367, 454–456.

- Lee, F.Y.; Lee, H.; Hubbert, M.L.; Edwards, P.A.; Zhang, Y. FXR, a multipurpose nuclear receptor. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006, 31, 572–580.

- Wang, Y.-D.; Chen, W.-D.; Moore, D.D.; Huang, W. FXR: A metabolic regulator and cell protector. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 1087–1095.

- Yan, N.; Yan, T.; Xia, Y.; Hao, H.; Wang, G.; Gonzalez, F.J. The pathophysiological function of non-gastrointestinal farnesoid X receptor. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 226, 107867.

- Sun, L.; Cai, J.; Gonzalez, F.J. The role of farnesoid X receptor in metabolic diseases, and gastrointestinal and liver cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 335–347.

- Zhang, T.; Feng, S.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Deng, Q.; Yang, W.; Li, J.; Pan, G. Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonists induce hepatocellular apoptosis and impair hepatic functions via FXR/SHP pathway. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 1829–1843.

- Namisaki, T.; Kaji, K.; Shimozato, N.; Kaya, D.; Ozutsumi, T.; Tsuji, Y.; Fujinaga, Y.; Kitagawa, K.; Furukawa, M.; Sato, S.; et al. Effect of combined farnesoid X receptor agonist and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker on ongoing hepatic fibrosis. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 41, 169–180.

- Malivindi, R.; Santoro, M.; De Rose, D.; Panza, S.; Gervasi, S.; Rago, V.; Aquila, S. Activated-farnesoid X receptor (FXR) expressed in human sperm alters its fertilising ability. Reproduction 2018, 156, 249–259.

- Yu, D.; Mattern, D.L.; Forman, B.M. An improved synthesis of 6α-ethylchenodeoxycholic acid (6ECDCA), a potent and selective agonist for the Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR). Steroids 2012, 77, 1335–1338.

- Lu, T.T.; Makishima, M.; Repa, J.J.; Schoonjans, K.; Kerr, T.A.; Auwerx, J.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Molecular Basis for Feedback Regulation of Bile Acid Synthesis by Nuclear Receptors. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 507–515.

- Chapman, R.W.; Lynch, K.D. Obeticholic acid-a new therapy in PBC and NASH. Br. Med. Bull. 2020, 133, 95–104.

- Zhang, J.H.; Nolan, J.D.; Kennie, S.L.; Johnston, I.M.; Dew, T.; Dixon, P.H.; Williamson, C.; Walters, J.R. Potent stimulation of fibroblast growth factor 19 expression in the human ileum by bile acids. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013, 304, G940–G948.

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.-D.; Chen, W.-D.; Wang, X.; Lou, G.; Liu, N.; Lin, M.; Forman, B.M.; Huang, W. Promotion of liver regeneration/repair by farnesoid X receptor in both liver and intestine in mice. Hepatology 2012, 56, 2336–2343.

- Kast, H.R.; Goodwin, B.; Tarr, P.T.; Jones, S.A.; Anisfeld, A.M.; Stoltz, C.M.; Tontonoz, P.; Kliewer, S.; Willson, T.M.; Edwards, P.A. Regulation of Multidrug Resistance-associated Protein 2 (ABCC2) by the Nuclear Receptors Pregnane X Receptor, Farnesoid X-activated Receptor, and Constitutive Androstane Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 2908–2915.

- Pircher, P.C.; Kitto, J.L.; Petrowski, M.L.; Tangirala, R.K.; Bischoff, E.D.; Schulman, I.G.; Westin, S.K. Farnesoid X Receptor Regulates Bile Acid-Amino Acid Conjugation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 27703–27711.

- van Golen, R.F.; Olthof, P.B.; Lionarons, D.A.; Reiniers, M.J.; Alles, L.K.; Uz, Z.; de Haan, L.; Ergin, B.; de Waart, D.R.; Maas, A.; et al. FXR agonist obeticholic acid induces liver growth but exacerbates biliary injury in rats with obstructive cholestasis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16529.

- Roda, A.; Aldini, R.; Camborata, C.; Spinozzi, S.; Franco, P.; Cont, M.; D’Errico, A.; Vasuri, F.; Degiovanni, A.; Maroni, L.; et al. Metabolic Profile of Obeticholic Acid and Endogenous Bile Acids in Rats with Decompensated Liver Cirrhosis. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2017, 10, 292–301.

- Guo, C.; LaCerte, C.; Edwards, J.E.; Brouwer, K.R.; Brouwer, K.L.R. Farnesoid X Receptor Agonists Obeticholic Acid and Chenodeoxycholic Acid Increase Bile Acid Efflux in Sandwich-Cultured Human Hepatocytes: Functional Evidence and Mechanisms. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2018, 365, 413–421.

- Xu, Y.; Li, F.; Zalzala, M.; Xu, J.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Adorini, L.; Lee, Y.K.; Yin, L.; Zhang, Y. Farnesoid X receptor activation increases reverse cholesterol transport by modulating bile acid composition and cholesterol absorption in mice. Hepatology 2016, 64, 1072–1085.

- Dash, A.; Figler, R.A.; Blackman, B.R.; Marukian, S.; Collado, M.S.; Lawson, M.J.; Hoang, S.A.; Mackey, A.J.; Manka, D.; Cole, B.K.; et al. Pharmacotoxicology of clinically-relevant concentrations of obeticholic acid in an organotypic human hepatocyte system. Toxicol. In Vitro 2017, 39, 93–103.

- Zhang, Y.; Jackson, J.P.; St Claire, R.L., 3rd; Freeman, K.; Brouwer, K.R.; Edwards, J.E. Obeticholic acid, a selective farnesoid X receptor agonist, regulates bile acid homeostasis in sandwich-cultured human hepatocytes. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2017, 5, e00329.

- Mencarelli, A.; Renga, B.; Distrutti, E.; Fiorucci, S. Antiatherosclerotic effect of farnesoid X receptor. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009, 296, H272–H281.

- Cipriani, S.; Mencarelli, A.; Palladino, G.; Fiorucci, S. FXR activation reverses insulin resistance and lipid abnormalities and protects against liver steatosis in Zucker (fa/fa) obese rats. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 771–784.

- de Oliveira, M.C.; Gilglioni, E.H.; de Boer, B.A.; Runge, J.H.; de Waart, D.R.; Salgueiro, C.L.; Ishii-Iwamoto, E.L.; Oude Elferink, R.P.; Gaemers, I.C. Bile acid receptor agonists INT747 and INT777 decrease oestrogen deficiency-related postmenopausal obesity and hepatic steatosis in mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 2054–2062.

- Briand, F.; Brousseau, E.; Quinsat, M.; Burcelin, R.; Sulpice, T. Obeticholic acid raises LDL-cholesterol and reduces HDL-cholesterol in the Diet-Induced NASH (DIN) hamster model. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 818, 449–456.

- Singh, A.B.; Dong, B.; Kraemer, F.B.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J. Farnesoid X Receptor Activation by Obeticholic Acid Elevates Liver Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor Expression by mRNA Stabilization and Reduces Plasma Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 2448–2459.

- Zhang, H.; Dong, M.; Liu, X. Obeticholic acid ameliorates obesity and hepatic steatosis by activating brown fat. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 991.

- Maneschi, E.; Vignozzi, L.; Morelli, A.; Mello, T.; Filippi, S.; Cellai, I.; Comeglio, P.; Sarchielli, E.; Calcagno, A.; Mazzanti, B.; et al. FXR activation normalizes insulin sensitivity in visceral preadipocytes of a rabbit model of MetS. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 218, 215–231.

- Mudaliar, S.; Henry, R.R.; Sanyal, A.J.; Morrow, L.; Marschall, H.U.; Kipnes, M.; Adorini, L.; Sciacca, C.I.; Clopton, P.; Castelloe, E.; et al. Efficacy and safety of the farnesoid X receptor agonist obeticholic acid in patients with type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 574–582.e571.

- Kunne, C.; Acco, A.; Duijst, S.; de Waart, D.R.; Paulusma, C.C.; Gaemers, I.; Oude Elferink, R.P. FXR-dependent reduction of hepatic steatosis in a bile salt deficient mouse model. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 739–746.

- Haczeyni, F.; Poekes, L.; Wang, H.; Mridha, A.R.; Barn, V.; Geoffrey Haigh, W.; Ioannou, G.N.; Yeh, M.M.; Leclercq, I.A.; Teoh, N.C.; et al. Obeticholic acid improves adipose morphometry and inflammation and reduces steatosis in dietary but not metabolic obesity in mice. Obesity 2017, 25, 155–165.

- Dong, B.; Young, M.; Liu, X.; Singh, A.B.; Liu, J. Regulation of lipid metabolism by obeticholic acid in hyperlipidemic hamsters. J. Lipid Res. 2017, 58, 350–363.

- Li, Y.T.; Swales, K.E.; Thomas, G.J.; Warner, T.D.; Bishop-Bailey, D. Farnesoid x receptor ligands inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell inflammation and migration. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 2606–2611.

- de Haan, L.R.; Verheij, J.; van Golen, R.F.; Horneffer-van der Sluis, V.; Lewis, M.R.; Beuers, U.H.W.; van Gulik, T.M.; Olde Damink, S.W.M.; Schaap, F.G.; Heger, M.; et al. Unaltered Liver Regeneration in Post-Cholestatic Rats Treated with the FXR Agonist Obeticholic Acid. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 260.

- Gai, Z.; Visentin, M.; Gui, T.; Zhao, L.; Thasler, W.E.; Häusler, S.; Hartling, I.; Cremonesi, A.; Hiller, C.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A. Effects of Farnesoid X Receptor Activation on Arachidonic Acid Metabolism, NF-kB Signaling, and Hepatic Inflammation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2018, 94, 802–811.

- Wang, Y.-D.; Chen, W.-D.; Wang, M.; Yu, D.; Forman, B.M.; Huang, W. Farnesoid X receptor antagonizes nuclear factor κB in hepatic inflammatory response. Hepatology 2008, 48, 1632–1643.

- Sinal, C.J.; Tohkin, M.; Miyata, M.; Ward, J.M.; Lambert, G.; Gonzalez, F.J. Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell 2000, 102, 731–744.

- Fiorucci, S.; Antonelli, E.; Rizzo, G.; Renga, B.; Mencarelli, A.; Riccardi, L.; Orlandi, S.; Pellicciari, R.; Morelli, A. The nuclear receptor SHP mediates inhibition of hepatic stellate cells by FXR and protects against liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 1497–1512.

- Fiorucci, S.; Rizzo, G.; Antonelli, E.; Renga, B.; Mencarelli, A.; Riccardi, L.; Morelli, A.; Pruzanski, M.; Pellicciari, R. Cross-talk between farnesoid-X-receptor (FXR) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma contributes to the antifibrotic activity of FXR ligands in rodent models of liver cirrhosis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 315, 58–68.

- Yang, Z.Y.; Liu, F.; Liu, P.H.; Guo, W.J.; Xiong, G.Y.; Pan, H.; Wei, L. Obeticholic acid improves hepatic steatosis and inflammation by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2017, 10, 8119–8129.

- Ding, Z.M.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, X.; Zou, H.; Yang, S.; Shen, Y.; Xu, J.; Workman, H.C.; Usborne, A.L.; Hua, H. Progression and Regression of Hepatic Lesions in a Mouse Model of NASH Induced by Dietary Intervention and Its Implications in Pharmacotherapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 410.

- Parés, A. Therapy of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Novel Approaches for Patients with Suboptimal Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid. Dig. Dis. 2015, 33 (Suppl. S2), 125–133.

- Huang, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, B.; Sun, K.; Wang, H.; Qin, L.; Bai, F.; Leng, Y.; Tang, W. A new mechanism of obeticholic acid on NASH treatment by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophage. Metabolism 2021, 120, 154797.

- Jouihan, H.; Will, S.; Guionaud, S.; Boland, M.L.; Oldham, S.; Ravn, P.; Celeste, A.; Trevaskis, J.L. Superior reductions in hepatic steatosis and fibrosis with co-administration of a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and obeticholic acid in mice. Mol. Metab. 2017, 6, 1360–1370.

- Zhou, J.; Huang, N.; Guo, Y.; Cui, S.; Ge, C.; He, Q.; Pan, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Hao, H. Combined obeticholic acid and apoptosis inhibitor treatment alleviates liver fibrosis. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2019, 9, 526–536.

- Roth, J.D.; Veidal, S.S.; Fensholdt, L.K.D.; Rigbolt, K.T.G.; Papazyan, R.; Nielsen, J.C.; Feigh, M.; Vrang, N.; Young, M.; Jelsing, J.; et al. Combined obeticholic acid and elafibranor treatment promotes additive liver histological improvements in a diet-induced ob/ob mouse model of biopsy-confirmed NASH. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9046.

- Li, W.C.; Zhao, S.X.; Ren, W.G.; Zhang, Y.G.; Wang, R.Q.; Kong, L.B.; Zhang, Q.S.; Nan, Y.M. Co-administration of obeticholic acid and simvastatin protects against high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 830.

- Nevens, F.; Andreone, P.; Mazzella, G.; Strasser, S.I.; Bowlus, C.; Invernizzi, P.; Drenth, J.P.; Pockros, P.J.; Regula, J.; Beuers, U.; et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Obeticholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 631–643.

- D’Amato, D.; De Vincentis, A.; Malinverno, F.; Viganò, M.; Alvaro, D.; Pompili, M.; Picciotto, A.; Palitti, V.P.; Russello, M.; Storato, S.; et al. Real-world experience with obeticholic acid in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. JHEP Rep. 2021, 3, 100248.

- Kowdley, K.V.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Levy, C.; Floreani, A.; Andreone, P.; LaRusso, N.F.; Shrestha, R.; Trotter, J.; Goldberg, D.; Rushbrook, S.; et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II study of obeticholic acid for primary sclerosing cholangitis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 94–101.

- Kowdley, K.V.; Luketic, V.; Chapman, R.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Poupon, R.; Schramm, C.; Vincent, C.; Rust, C.; Parés, A.; Mason, A.; et al. A randomized trial of obeticholic acid monotherapy in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Hepatology 2018, 67, 1890–1902.

- Younossi, Z.M.; Ratziu, V.; Loomba, R.; Rinella, M.; Anstee, Q.M.; Goodman, Z.; Bedossa, P.; Geier, A.; Beckebaum, S.; Newsome, P.N.; et al. Obeticholic acid for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Interim analysis from a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 2184–2196.

- Ratziu, V.; Sanyal, A.J.; Loomba, R.; Rinella, M.; Harrison, S.; Anstee, Q.M.; Goodman, Z.; Bedossa, P.; MacConell, L.; Shringarpure, R.; et al. REGENERATE: Design of a pivotal, randomised, phase 3 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of obeticholic acid in patients with fibrosis due to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2019, 84, 105803.

- Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Loomba, R.; Sanyal, A.J.; Lavine, J.E.; Van Natta, M.L.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Chalasani, N.; Dasarathy, S.; Diehl, A.M.; Hameed, B.; et al. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): A multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 956–965.

- Pockros, P.J.; Fuchs, M.; Freilich, B.; Schiff, E.; Kohli, A.; Lawitz, E.J.; Hellstern, P.A.; Owens-Grillo, J.; Van Biene, C.; Shringarpure, R.; et al. CONTROL: A randomized phase 2 study of obeticholic acid and atorvastatin on lipoproteins in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patients. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 2082–2093.

- Hirschfield, G.M.; Mason, A.; Luketic, V.; Lindor, K.; Gordon, S.C.; Mayo, M.; Kowdley, K.V.; Vincent, C.; Bodhenheimer, H.C., Jr.; Parés, A.; et al. Efficacy of obeticholic acid in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and inadequate response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 751–761.e758.

- Edwards, J.E.; LaCerte, C.; Peyret, T.; Gosselin, N.H.; Marier, J.F.; Hofmann, A.F.; Shapiro, D. Modeling and Experimental Studies of Obeticholic Acid Exposure and the Impact of Cirrhosis Stage. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2016, 9, 328–336.

- Samur, S.; Klebanoff, M.; Banken, R.; Pratt, D.S.; Chapman, R.; Ollendorf, D.A.; Loos, A.M.; Corey, K.; Hur, C.; Chhatwal, J. Long-term clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of obeticholic acid for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis. Hepatology 2017, 65, 920–928.

- Hameed, B.; Terrault, N.A.; Gill, R.M.; Loomba, R.; Chalasani, N.; Hoofnagle, J.H.; Van Natta, M.L. Clinical and metabolic effects associated with weight changes and obeticholic acid in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 47, 645–656.

- Trauner, M.; Nevens, F.; Shiffman, M.L.; Drenth, J.P.H.; Bowlus, C.L.; Vargas, V.; Andreone, P.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Pencek, R.; Malecha, E.S.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of obeticholic acid for patients with primary biliary cholangitis: 3-year results of an international open-label extension study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 445–453.

- Siddiqui, M.S.; Van Natta, M.L.; Connelly, M.A.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Tonascia, J.; Guy, C.; Loomba, R.; Dasarathy, S.; Wattacheril, J.; et al. Impact of obeticholic acid on the lipoprotein profile in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 25–33.

- Eaton, J.E.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Reddy, R.; Sathapathy, S.; Ali, B.; Kamath, P.S. Liver Injury in Patients With Cholestatic Liver Disease Treated with Obeticholic Acid. Hepatology 2020, 71, 1511–1514.

- Bowlus, C.L.; Pockros, P.J.; Kremer, A.E.; Parés, A.; Forman, L.M.; Drenth, J.P.H.; Ryder, S.D.; Terracciano, L.; Jin, Y.; Liberman, A.; et al. Long-Term Obeticholic Acid Therapy Improves Histological Endpoints in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 1170–1178.e1176.

- Kjærgaard, K.; Frisch, K.; Sørensen, M.; Munk, O.L.; Hofmann, A.F.; Horsager, J.; Schacht, A.C.; Erickson, M.; Shapiro, D.; Keiding, S. Obeticholic acid improves hepatic bile acid excretion in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 58–65.

- Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Obeticholic Acid in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Demographic Subgroup Analysis of 5-Year Results from the POISE Trial. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 17, 2–3.

- Younossi, Z.M.; Stepanova, M.; Nader, F.; Loomba, R.; Anstee, Q.M.; Ratziu, V.; Harrison, S.; Sanyal, A.J.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Barritt, A.S.; et al. Obeticholic Acid Impact on Quality of Life in Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: REGENERATE 18-Month Interim Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 2050–2058.e2012.

- Murillo Perez, C.F.; Fisher, H.; Hiu, S.; Kareithi, D.; Adekunle, F.; Mayne, T.; Malecha, E.; Ness, E.; van der Meer, A.J.; Lammers, W.J.; et al. Greater Transplant-Free Survival in Patients Receiving Obeticholic Acid for Primary Biliary Cholangitis in a Clinical Trial Setting Compared to Real-World External Controls. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 1630–1642.e1633.

- Ng, C.H.; Tang, A.S.P.; Xiao, J.; Wong, Z.Y.; Yong, J.N.; Fu, C.E.; Zeng, R.W.; Tan, C.; Wong, G.H.Z.; Teng, M.; et al. Safety and tolerability of obeticholic acid in chronic liver disease: A pooled analysis of 1878 individuals. Hepatol. Commun. 2023, 7, e0005.

- Harrison, S.A.; Bashir, M.R.; Lee, K.-J.; Shim-Lopez, J.; Lee, J.; Wagner, B.; Smith, N.D.; Chen, H.C.; Lawitz, E.J. A structurally optimized FXR agonist, MET409, reduced liver fat content over 12 weeks in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 25–33.

- Schramm, C.; Wedemeyer, H.; Mason, A.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Levy, C.; Kowdley, K.V.; Milkiewicz, P.; Janczewska, E.; Malova, E.S.; Sanni, J.; et al. Farnesoid X receptor agonist tropifexor attenuates cholestasis in a randomised trial in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. JHEP Rep. 2022, 4, 100544.

- Trauner, M.; Gulamhusein, A.; Hameed, B.; Caldwell, S.; Shiffman, M.L.; Landis, C.; Eksteen, B.; Agarwal, K.; Muir, A.; Rushbrook, S.; et al. The Nonsteroidal Farnesoid X Receptor Agonist Cilofexor (GS-9674) Improves Markers of Cholestasis and Liver Injury in Patients with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Hepatology 2019, 70, 788–801.

- Al-Khaifi, A.; Rudling, M.; Angelin, B. An FXR Agonist Reduces Bile Acid Synthesis Independently of Increases in FGF19 in Healthy Volunteers. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1012–1016.

More