Here we describe the pathophysiology of type II allergic asthma and the role that dendritic cells (DCs) play in the instruction of allergen specific, T-cell mediated immune responses. Moreover, we provide an overview of our current understanding pertinent to DCs that acquire tolerogenic properties and thus represent essential regulators of aberrant Th2 asthmatic responses.

In this review we describe the pathophysiology of type II allergic asthma and the role that dendritic cells (DCs) play in the instruction of allergen specific, T-cell mediated immune responses. Moreover, we provide an overview of our current understanding pertinent to DCs that acquire tolerogenic properties and thus represent essential regulators of aberrant Th2 asthmatic responses.

- allergic asthma, dendritic cells, tolerogenic

Note:Dear author, the following contents are excerpts from your papers. They are editable. And the entry will be online only after authors edit and submit it.

Definition:

Allergic asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways characterized by airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), chronic airway inflammation, and excessive T helper (Th) type 2 immune responses against harmless airborne allergens. Dendritic cells (DCs) represent the most potent antigen-presenting cells of the immune system that act as a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity. Pertinent to allergic asthma, distinct DC subsets are known to play a central role in initiating and maintaining allergen driven Th2 immune responses in the airways.

1. Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) denote the “professional” antigen presenting cells of our immune system and are responsible for the initiation and propagation of effective innate and subsequent adaptive immune responses [1]. DCs are highly specialized immune cells that constantly recognize and sample foreign antigens/allergens and infectious agents at mucosal sites. Upon antigen uptake, DCs migrate to secondary lymphoid tissues and efficiently activate naive CD4

+ T cells [2]. Depending on the DC subset involved, the cytokine micromilieu and the nature of the activation signal, DCs resourcefully prime CD4

T cells [2]. Depending on the DC subset involved, the cytokine micromilieu and the nature of the activation signal, DCs resourcefully prime CD4

+ T helper (Th) cells which subsequently differentiate in several distinct subsets, such as Th1, Th2, Th9, and Th17 cells [3]. Apart from the efficient activation of effector T cell-mediated immune responses, DCs are also critically involved in the maintenance of immune homeostasis. Immune homeostasis is accomplished through the employment of several tolerogenic mechanisms, such as the induction of T cell anergy, the instruction of regulatory T (Treg) cells, and the production of regulatory cytokines, such as, IL-10, IL-27, and TGF-beta [4]. It becomes evident that DCs represent an attractive cell-target that can be utilized in vaccination settings aimed at boosting inefficient immune responses for the treatment of infectious diseases and cancer [5][6]. Alternatively, DCs could be utilized to diminish aberrant immune responses in the context of chronic inflammation, autoimmunity, and allergy [5][6]. Pertinent to asthma, a growing body of evidence suggests that the therapeutic transfer of DCs with immunoregulatory properties suppresses aberrant Th2 allergic responses and prevents, or even reverses, established allergic airway inflammation in experimental asthma [7][8][9]. In the first part of this review we briefly describe the immunopathophysiology of type II allergic asthma, as well as the role that DCs play in the instruction of allergen-specific Th-cell mediated immune responses. Moreover, we provide an overview of our current understanding regarding DCs that acquire tolerogenic properties, thus representing critical controllers of excessive Th2-driven allergic airway inflammation in experimental asthma.

T helper (Th) cells which subsequently differentiate in several distinct subsets, such as Th1, Th2, Th9, and Th17 cells [3]. Apart from the efficient activation of effector T cell-mediated immune responses, DCs are also critically involved in the maintenance of immune homeostasis. Immune homeostasis is accomplished through the employment of several tolerogenic mechanisms, such as the induction of T cell anergy, the instruction of regulatory T (Treg) cells, and the production of regulatory cytokines, such as, IL-10, IL-27, and TGF-beta [4]. It becomes evident that DCs represent an attractive cell-target that can be utilized in vaccination settings aimed at boosting inefficient immune responses for the treatment of infectious diseases and cancer [5,6]. Alternatively, DCs could be utilized to diminish aberrant immune responses in the context of chronic inflammation, autoimmunity, and allergy [5,6]. Pertinent to asthma, a growing body of evidence suggests that the therapeutic transfer of DCs with immunoregulatory properties suppresses aberrant Th2 allergic responses and prevents, or even reverses, established allergic airway inflammation in experimental asthma [7,8,9]. In the first part of this review we briefly describe the immunopathophysiology of type II allergic asthma, as well as the role that DCs play in the instruction of allergen-specific Th-cell mediated immune responses. Moreover, we provide an overview of our current understanding regarding DCs that acquire tolerogenic properties, thus representing critical controllers of excessive Th2-driven allergic airway inflammation in experimental asthma.

2. DC Subsets and Their Role in the Regulation of Allergic Asthma

2.1. Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses in Lung Allergic Inflammation

2.1. Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses in Lung Allergic Inflammation

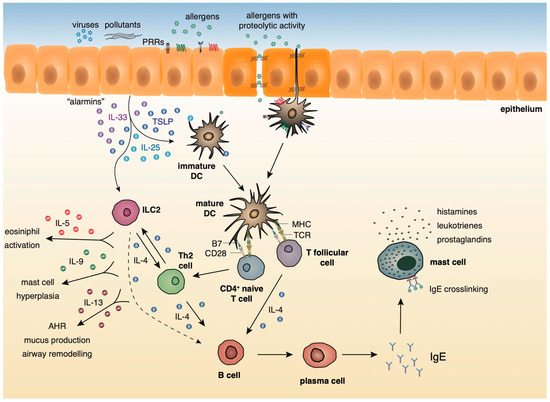

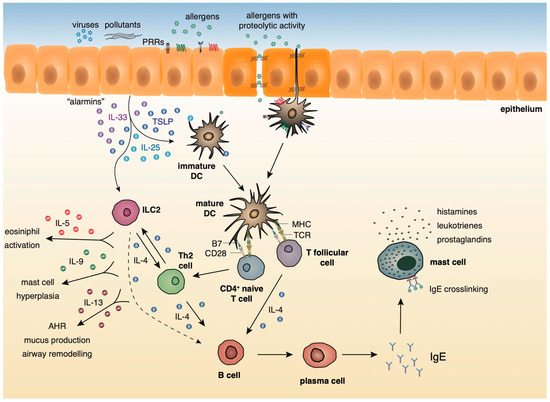

A growing body of evidence underlies the importance of the crosstalk between bronchial epithelial cells and DCs following allergen encounter during the initiation of asthmatic responses [2]. The asthmatic airway epithelium represents a vital supplier of cytokines termed “alarmins”, such as IL-25, IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and chemokines, including CCL5, CCL17, CCL11, and CCL22 that trigger Th2 cell polarization upon exposure to allergens, pollutants, and other pathogenic components [14,15,16,17,18,19]. After encountering airborne allergens in the airways, DCs process them into small peptides, generate MHC-peptide complexes and traffic through the lymphatics to the mediastinal lymph nodes (MLNs) where they present allergen components to naive CD4+ Th cells [20]. Recent studies have highlighted a critical role for group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) in type 2 immunity, as well as in asthma immunopathogenesis [21,22,23,24,25]. ILC2s are activated in response to TSLP, IL-25, and IL-33 signaling, and produce type 2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-13) [21,22,23,24,25] and prostaglandin [26], further enhancing Th2-driven allergic responses in the airways. Allergens that possess proteolytic activity, such as those derived from HDM, pollen grains, cockroach, and animal and fungal allergens, stimulate protease activated receptors expressed on the surface of DCs and disrupt epithelial tight junctions instigating inflammatory responses [27,28]. Additionally, environmental stimuli, such as respiratory viruses and air pollutants are also capable of disrupting tight junctions and impairing barrier function [29,30,31,32,33]. Furthermore, several allergens contain microbial components named pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that interact with pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) on DCs and airway epithelial cells, and serve as “danger signals” for the host immune response [34,35]. The interaction of allergen loaded DCs with naive Th cells leads to the differentiation of the latter into Th1, Th2, Th9, or Th17 cells, depending on the type and dose of allergen, as well as, the cytokine micromilieu [36]. In the presence of type 2 cytokines, allergen specific Th2 or T follicular helper cells (TFH) are generated. Th2 and ILC2 cells migrate towards the site of inflammation, where upon allergen challenge, produce type 2 cytokines (IL-5, IL-9, IL-13, etc.). IL-5 and IL-9 are critical for promoting tissue eosinophilia and mast cell hyperplasia, whereas IL- 13 stimulates mucus production by goblet cells and AHR [37]. Seminal studies by Halim and colleagues revealed that IL-13, secreted by ILC2s, stimulates CD11b+CD103− lung DCs to produce the chemokine CCL17, which in turn enhances the recruitment of CCR4+ memory Th2 cells. Moreover, the depletion of ILC2s in papain-sensitized mice during re-challenge resulted in significantly diminished numbers of IL-4-producing memory Th2 cells in the airways [38]. TFH cells represent a specialized T cell subset that upon interaction with allergen- specific B cells induces the production of IgE antibodies. The crosslinking of these allergen-specific IgE antibodies to the high-affinity FcεR on the surface of mast cells leads to the activation of the latter and the release of several inflammatory mediators, such as, histamine, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes [37] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Innate and adaptive type 2 immunity during allergic airway inflammation.

During the initiation of asthmatic responses, a plethora of cytokines and chemokines produced by the airway epithelium stimulates immature DCs that upon allergen encounter traffic to the MLNs and stimulate naive CD4+ Th cells. ILC2s, upon activation by the “alarmins”, produce type 2 cytokines further propagating allergic responses. In the presence of type 2 cytokines, allergen specific Th2 or TFH are generated. Th2 cells migrate towards the site of inflammation, where upon allergen challenge, produce mainly, IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13. IL-5 and IL-9 are critical for promoting tissue eosinophilia and mast cell hyperplasia, whereas IL- 13 stimulates mucus production by goblet cells and AHR. TFH cells produce IL-4 and, upon interaction with allergen-specific B cells, induce the production of IgE antibodies. The crosslinking of these allergen-specific IgE antibodies to the high-affinity FcεR on the surface of mast cells leads to the activation of the latter and the release of several inflammatory mediators, such as, histamines, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes.

A growing body of evidence underlies the importance of the crosstalk between bronchial epithelial cells and DCs following allergen encounter during the initiation of asthmatic responses

2.2. Localization and Phenotype of DC Subsets in the Lung

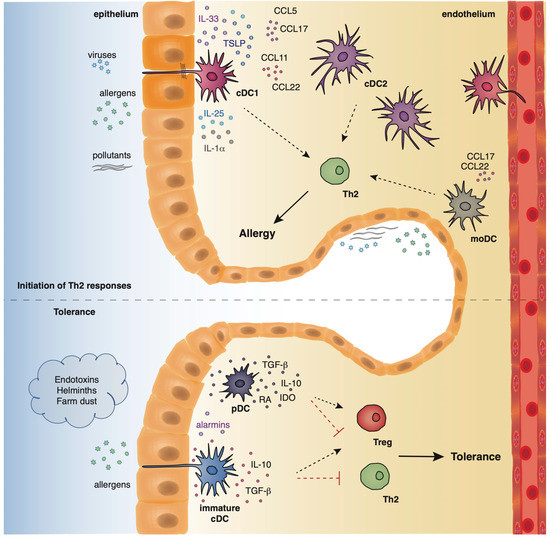

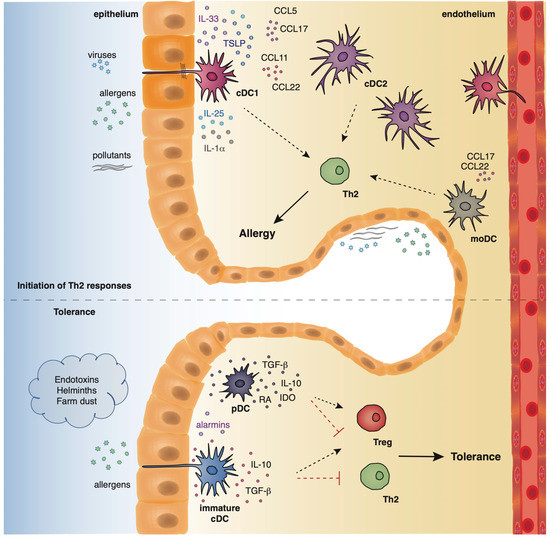

Dendritic cells originate from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow from where they start to traffic in order to populate the lymphatic tissues and other organs [39,40]. The divergence in the expression profile of several surface markers, as well as the functional properties of DCs has allowed researchers to classify and characterize different DC subsets that play essential roles in preserving immune homeostasis in the lungs, as well as promoting Th2 immune responses in allergic asthma. Under steady state conditions, mouse pulmonary DCs represent a heterogeneous cell population that mainly comprises of two types of conventional DCs (cDCs), the cDCs type 1 (cDCs1) and type 2 (cDCs2), and also a very small percentage of plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) [39,40]. Mouse cDCs which are characterized by high expression of the CD11c surface marker are found throughout the lungs, including the large conducting airways, lung parenchyma, alveolar compartment, pleura, and perivascular space. The integrin CD103 is a specific marker for the cDCs1 subset whereas cDCs2 express the cell surface marker, CD11b [41,42,43]. On the contrary, mouse pDCs express low levels of CD11c and are characterized by the expression of other characteristic surface markers, such as, CD45R (B220) and CD317 (PDCA1) [44]. pDCs reside predominantly in the conducting airways, although in a lower density, and have also been described to be present in the lung parenchyma [45]. Under inflammatory conditions, such as, exposure to allergens, pathogens, or pollutants, inflammatory monocyte-derived DCs (mo-DCs) are also recruited to the conducting airways and lung parenchyma [46] (Figure 2). Inflammatory DCs which can be either CD11b+ or CD103+ originate from Ly6C+ blood monocytes under the influence of a granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor [40,47].

Figure 2. The location and function of different DC subsets in the airways.

Pertinent to humans, DCs are generally categorized in analogous subgroups to their murine counterparts. Three pulmonary DCs subsets have been described in humans, two of myeloid origin (mDcs) and one population of pDCs. The mDC1 subset expresses BDCA1 (CD1c), whereas the mDC2 subset expresses BDCA3 (CD141). Human pDCs are mainly characterized by the expression of BDCA2 (CD123) [39,40]. It has been shown that BDCA1+ cDCs are increased in the airway epithelium of asthmatics with a high Th2 phenotype, whereas this is not observed in patients with a Th2 low profile [48]. Notably, using unbiased single-cell RNA sequencing, Villani and colleagues provided a revised taxonomy pertinent to human blood DCs. They identified 6 DC populations (DC1-DC6): DC1 cluster is characterized as CD141/BDCA-3+CLEC9A+, DC2 and DC3 clusters represent subdivisions of CD1c/BDCA-1+ cDCs, DC4 cluster is described as CD1c-CD141-CD11c+CD16+, DC5 is a cluster defined by the unique expression of the surface markers AXL and SIGLEC6, and DC6 is a cluster that corresponds to the interferon-producing CD123+CD303/BDCA-2+ pDCs [49,50]. Nevertheless, due to the lack of adequate lung material containing epithelium and interstitium from both healthy controls and asthmatics, the localization of human DC subsets in the asthmatic lung, during steady state and under inflammatory conditions, remains ill defined.

2.3. The Role of Human DC Subsets in Shaping Asthmatic Responses

Patients with allergic asthma display heightened numbers of mDC1s and mDC2s in the peripheral blood (PB), induced sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) upon allergen inhalation [65,66,67,68]. Nevertheless, upon allergen inhalation only the percentages of cDC2s are increased in bronchial tissues [68]. PB CD1c+ mDC2s loaded with Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus antigen P1 (Der p1) allergen-IgE immune complexes induced the release of IL-4 and concomitantly lowered IFN-γ-expression. As a result, the use of these DCs in in vitro co-cultures with naive T cells promoted Th2 cell differentiation [69]. Moreover, the co-culture of Der p1-loaded CD1c+ mDC2s from asthmatics with allogeneic CD4+ T cells from non-asthmatic, non-allergic donors promoted the differentiation of the latter towards a Th2 phenotype [70]. Furthermore, when TSLP-pulsed mDC2s from the same donors were used in the co-cultures, they drove the in vitro development of both Th2 and Th9 cells [70].

Pertinent to the numbers of pDCs in the PB of patients with asthma, there are contradictory results demonstrating that this subset is either increased or decreased [71,72]. Nevertheless, upon allergen challenge the numbers of pDCs are increased in the BAL and sputum of asthmatics [66,73]. During infancy, numbers of circulating pDCs are inversely correlated with symptoms of lower respiratory tract infections, wheezing and asthma diagnosis by 5 years of age [74]. Moreover, co-culture of Derp1–pulsed mo-DCs from HDM-sensitive patients with autologous CD4+ T cells resulted in the secretion of large amounts of IL-4 compared to CD4+ T cells stimulated with unpulsed DCs. These findings underlie the capacity of mo-DCs to orientate CD4+ T cells towards a Th2 response [75]. Importantly, IL-4 production by CD4+ T cells from allergic patients was dependent on CD86, as the administration of a blocking antibody against CD86 reduced the secretion of IL-4 [75].

2.4. The Role of Tolerogenic DCs in the Resolution of Allergic Airway Inflammation in the Airways

Under physiological conditions, in the absence of a “danger signal”, such as proinflammatory cytokines and microbial products, harmless environmental allergens cannot fully activate lung-derived cDCs or even recruit in the lungs novel inflammatory DCs subsets [76,77]. As a consequence, pulmonary tolerance is achieved as DCs remain in an immature state and are incapable of inducing effective T-cell responses [76,77]. Several studies have shown that DCs not only promote but can also restrain Th2-driven allergic responses through instructing the generation of Treg cells and/or secreting cytokines with immunosuppressive properties, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, suggesting that DCs have acquired tolerogenic/immunosuppressive properties [78,79]. It has been demonstrated that CD103+ DCs from OVA-tolerized mice efficiently induced the de novo generation of CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells, a process mediated by retinaldehyde dehydrogenase and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ [78,79]. Importantly, OVA-tolerized Batf3−/− mice that lack CD103+ DCs showed increased signs of allergic airway inflammation compared to OVA-tolerized WT mice, underlying the importance of CD103+ DCs in the maintenance of pulmonary tolerance [78]. In line with the aforementioned studies, CD103-/- mice sensitized and challenged with OVA or HDM exhibited increased eosinophilic infiltration, severe tissue inflammation, and heightened IL-5 and IFN-γ secretion from lung cells compared to WT mice, strengthening the notion that CD103 DCs display an important role in the control of airway inflammation in asthma [79,80]. Notably, using a HDM-induced chronic asthma model, the authors showed that HDM-immunized Batf3–/– mice developed increased eosinophil and neutrophil influx, enhanced airway inflammation, goblet cell metaplasia, mucus production, and airway collagen deposition compared to WT mice [80]. It has been also demonstrated that in OVA-sensitized and challenged mice, administration of H. pylori reduces AHR, bronchoalveolar eosinophilia, pulmonary inflammation, and Th2 cytokine production. Notably, CD103+ DCs are required for H. pylori-induced protection against allergic airway inflammation as BATF3−/− mice were significantly less protected than WT mice against allergen-induced asthma upon infection with H. pylori [81].

Pertinent to the role of pDCs in the regulation of asthmatic responses, several studies have demonstrated that pDCs confer protection against allergic airway inflammation through at least the instruction of T reg cells [90,91]. Notably, the depletion of pDC before the sensitization phase with Ova resulted in increased lung inflammation and Th2 cell cytokine production from MLNs compared to WT mice with sufficient numbers of pDCs, revealing that pDCs restrain sensitization to otherwise harmless tolerogenic protein antigens [92]. In line with the above, the in vivo depletion of pDCs before Ova challenge resulted in heightened numbers of eosinophils and lymphocytes in the airways of mice [93]. Notably, the in vivo administration of OVA-pulsed pDCs before allergen challenge resulted in a strong decrease in the numbers of BAL fluid eosinophils and lymphocytes, underlying the regulatory role of pDCs in allergic airway inflammation [93]. Moreover, the in vivo transfer of Ova-pulsed CD8α+β− or CD8α+β+ pDCs before allergen sensitization and challenge prevented the induction of AHR and lung inflammation and decreased Th2 cell cytokine production from MLNs and OVA-specific IgE serum levels [64]. Nevertheless, another study showed that in an acute model of allergic airway inflammation, pDC depletion after Ova challenge reduced AHR, the numbers of eosinophils and T cells in the BAL fluid, as well as peribronchial and perivascular inflammation and OVA-specific Th2 responses in MLNs, suggesting that pDCs promote allergic inflammatory responses in the airways once disease has been established [94].

Allergens with proteolytic activity, air pollutants, and viruses (asthma risk factors) stimulate the epithelium to produce alarmins and inflammatory factors that activate cDCs and moDCs which in turn initiate and propagate Th2-driven allergic responses. On the contrary, exposure to endotoxins, helminths, and farm dust reduces the epithelial responses, favoring the maintenance of cDCs in an immature state. Along with immature cDCs, pDCs produce immunosuppressive factors, facilitating the establishment of pulmonary tolerance.

3. Conclusions

Emerging evidence underlies the vital role that DCs play in fine tuning the balance between protective immunity and pulmonary tolerance in the airways in the context of allergic asthma. The functions of different DC subsets during the initiation and propagation of allergic asthma are very complex and highly dependent on both the nature and the levels of inhaled allergen, route of administration, composition of the local microenvironment, localization of DCs in the airways, as well as the phase of the immune response. As mentioned above, several studies have revealed that cDC1s, cDC2s, and mo-DCs are critical in orchestrating inflammatory responses in the airways, whereas CD103+ cDC1s and pDCs mainly contribute to the resolution of inflammation in the airways through the release of immunoregulatory cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, and the instruction of Treg cells. Although vaccination strategies involving the therapeutic transfer of tolerogenic immune cells are increasingly being utilized to limit detrimental self-reactive responses in autoimmune diseases, their use in the control of allergic responses has not been exploited.

Since DCs represent major drivers of immune polarization, they could be used as potential therapeutic targets in several diseases, including allergic asthma. Currently, allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT), involving exposure of individuals to escalating concentrations of an allergen, represents the only approved therapy for the control of allergic disorders, including asthma (108). The primary objective of AIT is to reestablish peripheral immune tolerance towards allergens, and diminish early- and late-phase allergic reactions through the induction of allergen-specific regulatory cell subsets, the production of suppressor cytokines (e.g., IL-10 and TGF-b) and inhibitory molecules (e.g., PD-1 and CTLA-4) and limitation of IgE production [106]. Towards the same direction, the administration of genetically engineered tolerogenic DCs could induce allergen-specific tolerance, holding the potential to be used as a therapeutic regime in allergic disorders. Indeed, monocyte-derived DCs from atopic individuals, treated ex vivo with the immunosuppressive agent IL-10, were able to suppress allergen-induced T-cell proliferation of autologous naive and memory CD4+ T helper cells and type 2 cytokine release [107]. In the context of contact dermatitis, dexamethasone-treated DCs from the peripheral blood of individuals with IgE-mediated latex allergy restrain allergen-specific T cell proliferation and IgE production in vitro and induce the generation of IL-10-producing Tregs [108]. A better understanding of the underlying cellular and molecular pathways involved in the generation of novel DC subsets that possess immunosuppressive properties may facilitate the design of novel DC-based immunotherapies for the re-establishment of tolerance in the airways.

. The asthmatic airway epithelium represents a vital supplier of cytokines termed “alarmins”, such as IL-25, IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and chemokines, including CCL5, CCL17, CCL11, and CCL22 that trigger Th2 cell polarization upon exposure to allergens, pollutants, and other pathogenic components

. After encountering airborne allergens in the airways, DCs process them into small peptides, generate MHC-peptide complexes and traffic through the lymphatics to the mediastinal lymph nodes (MLNs) where they present allergen components to naive CD4+ Th cells [16]. Recent studies have highlighted a critical role for group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) in type 2 immunity, as well as in asthma immunopathogenesis [17][18][19][20][21]. ILC2s are activated in response to TSLP, IL-25, and IL-33 signaling, and produce type 2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-13) [17][18][19][20][21] and prostaglandin [22], further enhancing Th2-driven allergic responses in the airways. Allergens that possess proteolytic activity, such as those derived from HDM, pollen grains, cockroach, and animal and fungal allergens, stimulate protease activated receptors expressed on the surface of DCs and disrupt epithelial tight junctions instigating inflammatory responses [23][24]. Additionally, environmental stimuli, such as respiratory viruses and air pollutants are also capable of disrupting tight junctions and impairing barrier function [25][26][27][28][29]. Furthermore, several allergens contain microbial components named pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that interact with pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) on DCs and airway epithelial cells, and serve as “danger signals” for the host immune response [30][31]. The interaction of allergen loaded DCs with naive Th cells leads to the differentiation of the latter into Th1, Th2, Th9, or Th17 cells, depending on the type and dose of allergen, as well as, the cytokine micromilieu [32]. In the presence of type 2 cytokines, allergen specific Th2 or T follicular helper cells (TFH) are generated. Th2 and ILC2 cells migrate towards the site of inflammation, where upon allergen challenge, produce type 2 cytokines (IL-5, IL-9, IL-13, etc.). IL-5 and IL-9 are critical for promoting tissue eosinophilia and mast cell hyperplasia, whereas IL- 13 stimulates mucus production by goblet cells and AHR [33]. Seminal studies by Halim and colleagues revealed that IL-13, secreted by ILC2s, stimulates CD11b+CD103− lung DCs to produce the chemokine CCL17, which in turn enhances the recruitment of CCR4+ memory Th2 cells. Moreover, the depletion of ILC2s in papain-sensitized mice during re-challenge resulted in significantly diminished numbers of IL-4-producing memory Th2 cells in the airways [34]. TFH cells represent a specialized T cell subset that upon interaction with allergen- specific B cells induces the production of IgE antibodies. The crosslinking of these allergen-specific IgE antibodies to the high-affinity FcεR on the surface of mast cells leads to the activation of the latter and the release of several inflammatory mediators, such as, histamine, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes [33] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Innate and adaptive type 2 immunity during allergic airway inflammation.

During the initiation of asthmatic responses, a plethora of cytokines and chemokines produced by the airway epithelium stimulates immature DCs that upon allergen encounter traffic to the MLNs and stimulate naive CD4+ Th cells. ILC2s, upon activation by the “alarmins”, produce type 2 cytokines further propagating allergic responses. In the presence of type 2 cytokines, allergen specific Th2 or TFH are generated. Th2 cells migrate towards the site of inflammation, where upon allergen challenge, produce mainly, IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13. IL-5 and IL-9 are critical for promoting tissue eosinophilia and mast cell hyperplasia, whereas IL- 13 stimulates mucus production by goblet cells and AHR. TFH cells produce IL-4 and, upon interaction with allergen-specific B cells, induce the production of IgE antibodies. The crosslinking of these allergen-specific IgE antibodies to the high-affinity FcεR on the surface of mast cells leads to the activation of the latter and the release of several inflammatory mediators, such as, histamines, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes.

2.2. Localization and Phenotype of DC Subsets in the Lung

Dendritic cells originate from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow from where they start to traffic in order to populate the lymphatic tissues and other organs [35][36]]. The divergence in the expression profile of several surface markers, as well as the functional properties of DCs has allowed researchers to classify and characterize different DC subsets that play essential roles in preserving immune homeostasis in the lungs, as well as promoting Th2 immune responses in allergic asthma. Under steady state conditions, mouse pulmonary DCs represent a heterogeneous cell population that mainly comprises of two types of conventional DCs (cDCs), the cDCs type 1 (cDCs1) and type 2 (cDCs2), and also a very small percentage of plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) [35][36]. Mouse cDCs which are characterized by high expression of the CD11c surface marker are found throughout the lungs, including the large conducting airways, lung parenchyma, alveolar compartment, pleura, and perivascular space. The integrin CD103 is a specific marker for the cDCs1 subset whereas cDCs2 express the cell surface marker, CD11b [37][38][39]. On the contrary, mouse pDCs express low levels of CD11c and are characterized by the expression of other characteristic surface markers, such as, CD45R (B220) and CD317 (PDCA1) [40]. pDCs reside predominantly in the conducting airways, although in a lower density, and have also been described to be present in the lung parenchyma [41]. Under inflammatory conditions, such as, exposure to allergens, pathogens, or pollutants, inflammatory monocyte-derived DCs (mo-DCs) are also recruited to the conducting airways and lung parenchyma [42] (Figure 2). Inflammatory DCs which can be either CD11b+ or CD103+ originate from Ly6C+ blood monocytes under the influence of a granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor [36][43].

Figure 2. The location and function of different DC subsets in the airways.

Pertinent to humans, DCs are generally categorized in analogous subgroups to their murine counterparts. Three pulmonary DCs subsets have been described in humans, two of myeloid origin (mDcs) and one population of pDCs. The mDC1 subset expresses BDCA1 (CD1c), whereas the mDC2 subset expresses BDCA3 (CD141). Human pDCs are mainly characterized by the expression of BDCA2 (CD123) [35][36]. It has been shown that BDCA1+ cDCs are increased in the airway epithelium of asthmatics with a high Th2 phenotype, whereas this is not observed in patients with a Th2 low profile [44]. Notably, using unbiased single-cell RNA sequencing, Villani and colleagues provided a revised taxonomy pertinent to human blood DCs. They identified 6 DC populations (DC1-DC6): DC1 cluster is characterized as CD141/BDCA-3+CLEC9A+, DC2 and DC3 clusters represent subdivisions of CD1c/BDCA-1+ cDCs, DC4 cluster is described as CD1c-CD141-CD11c+CD16+, DC5 is a cluster defined by the unique expression of the surface markers AXL and SIGLEC6, and DC6 is a cluster that corresponds to the interferon-producing CD123+CD303/BDCA-2+ pDCs [45][46]. Nevertheless, due to the lack of adequate lung material containing epithelium and interstitium from both healthy controls and asthmatics, the localization of human DC subsets in the asthmatic lung, during steady state and under inflammatory conditions, remains ill defined.

2.3. The Role of Human DC Subsets in Shaping Asthmatic Responses

Patients with allergic asthma display heightened numbers of mDC1s and mDC2s in the peripheral blood (PB), induced sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) upon allergen inhalation [47][48][49][50]. Nevertheless, upon allergen inhalation only the percentages of cDC2s are increased in bronchial tissues [50]. PB CD1c+ mDC2s loaded with Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus antigen P1 (Der p1) allergen-IgE immune complexes induced the release of IL-4 and concomitantly lowered IFN-γ-expression. As a result, the use of these DCs in in vitro co-cultures with naive T cells promoted Th2 cell differentiation [51]. Moreover, the co-culture of Der p1-loaded CD1c+ mDC2s from asthmatics with allogeneic CD4+ T cells from non-asthmatic, non-allergic donors promoted the differentiation of the latter towards a Th2 phenotype [52]. Furthermore, when TSLP-pulsed mDC2s from the same donors were used in the co-cultures, they drove the in vitro development of both Th2 and Th9 cells [52].

Pertinent to the numbers of pDCs in the PB of patients with asthma, there are contradictory results demonstrating that this subset is either increased or decreased [53][54]. Nevertheless, upon allergen challenge the numbers of pDCs are increased in the BAL and sputum of asthmatics [48][55]. During infancy, numbers of circulating pDCs are inversely correlated with symptoms of lower respiratory tract infections, wheezing and asthma diagnosis by 5 years of age [56]. Moreover, co-culture of Derp1–pulsed mo-DCs from HDM-sensitive patients with autologous CD4+ T cells resulted in the secretion of large amounts of IL-4 compared to CD4+ T cells stimulated with unpulsed DCs. These findings underlie the capacity of mo-DCs to orientate CD4+ T cells towards a Th2 response [57]. Importantly, IL-4 production by CD4+ T cells from allergic patients was dependent on CD86, as the administration of a blocking antibody against CD86 reduced the secretion of IL-4 [57].

2.4. The Role of Tolerogenic DCs in the Resolution of Allergic Airway Inflammation in the Airways

Under physiological conditions, in the absence of a “danger signal”, such as proinflammatory cytokines and microbial products, harmless environmental allergens cannot fully activate lung-derived cDCs or even recruit in the lungs novel inflammatory DCs subsets [58][59]. As a consequence, pulmonary tolerance is achieved as DCs remain in an immature state and are incapable of inducing effective T-cell responses [58][59]. Several studies have shown that DCs not only promote but can also restrain Th2-driven allergic responses through instructing the generation of Treg cells and/or secreting cytokines with immunosuppressive properties, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, suggesting that DCs have acquired tolerogenic/immunosuppressive properties [60][61]. It has been demonstrated that CD103+ DCs from OVA-tolerized mice efficiently induced the de novo generation of CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells, a process mediated by retinaldehyde dehydrogenase and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ [60][61]. Importantly, OVA-tolerized Batf3−/− mice that lack CD103+ DCs showed increased signs of allergic airway inflammation compared to OVA-tolerized WT mice, underlying the importance of CD103+ DCs in the maintenance of pulmonary tolerance [60]. In line with the aforementioned studies, CD103-/- mice sensitized and challenged with OVA or HDM exhibited increased eosinophilic infiltration, severe tissue inflammation, and heightened IL-5 and IFN-γ secretion from lung cells compared to WT mice, strengthening the notion that CD103 DCs display an important role in the control of airway inflammation in asthma [61][62]. Notably, using a HDM-induced chronic asthma model, the authors showed that HDM-immunized Batf3–/– mice developed increased eosinophil and neutrophil influx, enhanced airway inflammation, goblet cell metaplasia, mucus production, and airway collagen deposition compared to WT mice [62]. It has been also demonstrated that in OVA-sensitized and challenged mice, administration of H. pylori reduces AHR, bronchoalveolar eosinophilia, pulmonary inflammation, and Th2 cytokine production. Notably, CD103+ DCs are required for H. pylori-induced protection against allergic airway inflammation as BATF3−/− mice were significantly less protected than WT mice against allergen-induced asthma upon infection with H. pylori [63].

Pertinent to the role of pDCs in the regulation of asthmatic responses, several studies have demonstrated that pDCs confer protection against allergic airway inflammation through at least the instruction of T reg cells [64][65]. Notably, the depletion of pDC before the sensitization phase with Ova resulted in increased lung inflammation and Th2 cell cytokine production from MLNs compared to WT mice with sufficient numbers of pDCs, revealing that pDCs restrain sensitization to otherwise harmless tolerogenic protein antigens [66]. In line with the above, the in vivo depletion of pDCs before Ova challenge resulted in heightened numbers of eosinophils and lymphocytes in the airways of mice [67]. Notably, the in vivo administration of OVA-pulsed pDCs before allergen challenge resulted in a strong decrease in the numbers of BAL fluid eosinophils and lymphocytes, underlying the regulatory role of pDCs in allergic airway inflammation [67]. Moreover, the in vivo transfer of Ova-pulsed CD8α+β− or CD8α+β+ pDCs before allergen sensitization and challenge prevented the induction of AHR and lung inflammation and decreased Th2 cell cytokine production from MLNs and OVA-specific IgE serum levels [68]. Nevertheless, another study showed that in an acute model of allergic airway inflammation, pDC depletion after Ova challenge reduced AHR, the numbers of eosinophils and T cells in the BAL fluid, as well as peribronchial and perivascular inflammation and OVA-specific Th2 responses in MLNs, suggesting that pDCs promote allergic inflammatory responses in the airways once disease has been established [69].

Allergens with proteolytic activity, air pollutants, and viruses (asthma risk factors) stimulate the epithelium to produce alarmins and inflammatory factors that activate cDCs and moDCs which in turn initiate and propagate Th2-driven allergic responses. On the contrary, exposure to endotoxins, helminths, and farm dust reduces the epithelial responses, favoring the maintenance of cDCs in an immature state. Along with immature cDCs, pDCs produce immunosuppressive factors, facilitating the establishment of pulmonary tolerance.

3. Conclusions

Emerging evidence underlies the vital role that DCs play in fine tuning the balance between protective immunity and pulmonary tolerance in the airways in the context of allergic asthma. The functions of different DC subsets during the initiation and propagation of allergic asthma are very complex and highly dependent on both the nature and the levels of inhaled allergen, route of administration, composition of the local microenvironment, localization of DCs in the airways, as well as the phase of the immune response. As mentioned above, several studies have revealed that cDC1s, cDC2s, and mo-DCs are critical in orchestrating inflammatory responses in the airways, whereas CD103+ cDC1s and pDCs mainly contribute to the resolution of inflammation in the airways through the release of immunoregulatory cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, and the instruction of Treg cells. Although vaccination strategies involving the therapeutic transfer of tolerogenic immune cells are increasingly being utilized to limit detrimental self-reactive responses in autoimmune diseases, their use in the control of allergic responses has not been exploited.

Since DCs represent major drivers of immune polarization, they could be used as potential therapeutic targets in several diseases, including allergic asthma. Currently, allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT), involving exposure of individuals to escalating concentrations of an allergen, represents the only approved therapy for the control of allergic disorders, including asthma (108). The primary objective of AIT is to reestablish peripheral immune tolerance towards allergens, and diminish early- and late-phase allergic reactions through the induction of allergen-specific regulatory cell subsets, the production of suppressor cytokines (e.g., IL-10 and TGF-b) and inhibitory molecules (e.g., PD-1 and CTLA-4) and limitation of IgE production [70]. Towards the same direction, the administration of genetically engineered tolerogenic DCs could induce allergen-specific tolerance, holding the potential to be used as a therapeutic regime in allergic disorders. Indeed, monocyte-derived DCs from atopic individuals, treated ex vivo with the immunosuppressive agent IL-10, were able to suppress allergen-induced T-cell proliferation of autologous naive and memory CD4+ T helper cells and type 2 cytokine release [71]. In the context of contact dermatitis, dexamethasone-treated DCs from the peripheral blood of individuals with IgE-mediated latex allergy restrain allergen-specific T cell proliferation and IgE production in vitro and induce the generation of IL-10-producing Tregs [72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101]. A better understanding of the underlying cellular and molecular pathways involved in the generation of novel DC subsets that possess immunosuppressive properties may facilitate the design of novel DC-based immunotherapies for the re-establishment of tolerance in the airways.

[102][103][104][105][106][107][108]

References

- Schuijs, M.J.; Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N. Professional and ‘Amateur’ Antigen-Presenting Cells In Type 2 Immunity. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 22–34, doi:10.1016/j.it.2018.11.001.

- Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N. Barrier Epithelial Cells and the Control of Type 2 Immunity. Immunity 2015, 43, 29–40, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.007.

- Roy, S.; Rizvi, Z.A.; Awasthi, A. Metabolic Checkpoints in Differentiation of Helper T Cells in Tissue Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3036, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.03036.

- Schülke, S. Induction of Interleukin-10 Producing Dendritic Cells As a Tool to Suppress Allergen-Specific T Helper 2 Responses. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 455, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00455.

- Gaurav, R.; Agrawal, D.K. Clinical view on the importance of dendritic cells in asthma. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2013, 10, 899–919, doi:10.1586/1744666X.2013.837260.

- Hasegawa, H.; Matsumoto, T. Mechanisms of Tolerance Induction by Dendritic Cells In Vivo. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 350, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00350.

- Oertli, M.; Sundquist, M.; Hitzler, I.; Engler, D.B.; Arnold, I.C.; Reuter, S.; Maxeiner, J.; Hansson, M.; Taube, C.; Quiding-Järbrink, M.; et al. DC-derived IL-18 drives Treg differentiation, murine Helicobacter pylori-specific immune tolerance, and asthma protection. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 1082–1096, doi:10.1172/JCI61029.

- Hammad, H.; Kool, M.; Soullié, T.; Narumiya, S.; Trottein, F.; Hoogsteden, H.C.; Lambrecht, B.N. Activation of the D prostanoid 1 receptor suppresses asthma by modulation of lung dendritic cell function and induction of regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 357–367, doi:10.1084/jem.20061196.

- Semitekolou, M.; Morianos, I.; Banos, A.; Konstantopoulos, D.; Adamou-Tzani, M.; Sparwasser, T.; Xanthou, G. Dendritic cells conditioned by activin A-induced regulatory T cells exhibit enhanced tolerogenic properties and protect against experimental asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 671–684, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.03.047.

- Fort, M.M.; Cheung, J.; Yen, D.; Li, J.; Zurawski, S.M.; Lo, S.; Menon, S.; Clifford, T.; Hunte, B.; Lesley, R.; et al. IL-25 induces IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 pathologies and Th2-associated pathologies in vivo. Immunity 2001, 15, 985–995, doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00243-6.Theofani, E.; Semitekolou, M.; Morianos, I.; Samitas, K.; Xanthou, G. Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Severe Asthma. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1615, doi:10.3390/jcm8101615.

- Schmitz, J.; Owyang, A.; Oldham, E.; Song, Y.; Murphy, E.; McClanahan, T.K.; Zurawski, G.; Moshrefi, M.; Qin, J.; Li, X.; et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type-2 associated cytokines. Immunity 2005, 23, 479–490, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015.Holgate, S.T.; Holloway, J.; Wilson, S.; Howarth, P.H.; Haitchi, H.M.; Babu, S.; Davies, D.E. Understanding the pathophysiology of severe asthma to generate new therapeutic opportunities. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 496–506, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.039.

- Wang, Y.-H.; Angkasekwinai, P.; Lu, N.; Voo, K.S.; Arima, K.; Hanabuchi, S.; Hippe, A.; Corrigan, C.J.; Dong, C.; Homey, B.; et al. IL-25 augments type 2 immune responses by enhancing the expansion and functions of TSLP-DC-activated Th2 memory cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 1837–1847, doi:10.1084/jem.20070406.Wenzel, S.E. Asthma phenotypes: The evolution from clinical to molecular approaches. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 716–725, doi:10.1038/nm.2678.

- Ying, S.; O’Connor, B.; Ratoff, J.; Meng, Q.; Fang, C.; Cousins, D.; Zhang, G.; Gu, S.; Gao, Z.; Shamji, B.; et al. Expression and cellular provenance of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and chemokines in patients with severe asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 2790–2798, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2790.Finotto, S. Resolution of allergic asthma. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019, 41, 665–674, doi:10.1007/s00281-019-00770-3.

- Zhou, B.; Comeau, M.R.; De Smedt, T.; Liggitt, H.D.; Dahl, M.E.; Lewis, D.B.; Gyarmati, D.; Aye, T.; Campbell, D.J.; Ziegler, S.F. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin as a key initiator of allergic airway inflammation in mice. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 1047–1053, doi:10.1038/ni1247.Fort, M.M.; Cheung, J.; Yen, D.; Li, J.; Zurawski, S.M.; Lo, S.; Menon, S.; Clifford, T.; Hunte, B.; Lesley, R.; et al. IL-25 induces IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 pathologies and Th2-associated pathologies in vivo. Immunity 2001, 15, 985–995, doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00243-6.

- Kearley, J.; Buckland, K.F.; Mathie, S.A.; Lloyd, C.M. Resolution of allergic inflammation and airway hyper-reactivity is dependent upon disruption of the T1/ ST2–IL-33 pathway. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2009, 179, 772–781, doi:10.1164/rccm.200805-666OC.Schmitz, J.; Owyang, A.; Oldham, E.; Song, Y.; Murphy, E.; McClanahan, T.K.; Zurawski, G.; Moshrefi, M.; Qin, J.; Li, X.; et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type-2 associated cytokines. Immunity 2005, 23, 479–490, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015.

- Banchereau, J.; Steinman, R.M. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 1998, 392, 245–252, doi:10.1038/32588.Wang, Y.-H.; Angkasekwinai, P.; Lu, N.; Voo, K.S.; Arima, K.; Hanabuchi, S.; Hippe, A.; Corrigan, C.J.; Dong, C.; Homey, B.; et al. IL-25 augments type 2 immune responses by enhancing the expansion and functions of TSLP-DC-activated Th2 memory cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 1837–1847, doi:10.1084/jem.20070406.

- Neill, D.R.; Wong, S.H.; Bellosi, A.; Flynn, R.J.; Daly, M.; Langford, T.K.A.; Bucks, C.; Kane, C.M.; Fallon, P.D.; Pannell, R.; et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature 2010, 464, 1367–1370, doi:10.1038/nature08900.Ying, S.; O’Connor, B.; Ratoff, J.; Meng, Q.; Fang, C.; Cousins, D.; Zhang, G.; Gu, S.; Gao, Z.; Shamji, B.; et al. Expression and cellular provenance of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and chemokines in patients with severe asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 2790–2798, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2790.

- Moro, K.; Yamada, T.; Tanabe, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Ikawa, T.; Kawamoto, H.; Furusawa, J.; Ohtani, M.; Fujii, H.; Koyasu, S. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature 2010, 463, 540–544, doi:10.1038/nature08636.Zhou, B.; Comeau, M.R.; De Smedt, T.; Liggitt, H.D.; Dahl, M.E.; Lewis, D.B.; Gyarmati, D.; Aye, T.; Campbell, D.J.; Ziegler, S.F. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin as a key initiator of allergic airway inflammation in mice. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 1047–1053, doi:10.1038/ni1247.

- Price, A.E.; Liang, H.E.; Sullivan, B.M.; Reinhardt, R.L.; Eisley, C.J.; Erle, D.J.; Locksley, R.M. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11489–11494, doi:10.1073/pnas.1003988107.Kearley, J.; Buckland, K.F.; Mathie, S.A.; Lloyd, C.M. Resolution of allergic inflammation and airway hyper-reactivity is dependent upon disruption of the T1/ ST2–IL-33 pathway. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2009, 179, 772–781, doi:10.1164/rccm.200805-666OC.

- Saenz, S.A.; Siracusa, M.C.; Perrigoue, J.G.; Spencer, S.P.; Urban, J.F.; Tocker, J.E.; Budelsky, A.L.; Kleinschek, M.A.; Kastelein, R.A.; Kambayashi, T.; et al. IL25 elicits a multipotent progenitor cell population that promotes T(H)2 cytokine responses. Nature 2010, 464, 1362–1366, doi:10.1038/nature08901.Banchereau, J.; Steinman, R.M. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 1998, 392, 245–252, doi:10.1038/32588.

- Barlow, J.L.; McKenzie, A.N. Type-2 innate lymphoid cells in human allergic disease. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 14, 397–403, doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000090.Neill, D.R.; Wong, S.H.; Bellosi, A.; Flynn, R.J.; Daly, M.; Langford, T.K.A.; Bucks, C.; Kane, C.M.; Fallon, P.D.; Pannell, R.; et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature 2010, 464, 1367–1370, doi:10.1038/nature08900.

- Chang, J.E.; Doherty, T.A.; Baum, R.; Broide, D. Prostaglandin D2 regulates human type 2 innate lymphoid cell chemotaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 899–901, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.020.Moro, K.; Yamada, T.; Tanabe, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Ikawa, T.; Kawamoto, H.; Furusawa, J.; Ohtani, M.; Fujii, H.; Koyasu, S. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature 2010, 463, 540–544, doi:10.1038/nature08636.

- Lewkowich, I.P.; Day, S.B.; Ledford, J.R.; Zhou, P.; Dienger, K.; Wills-Karp, M.; Page, K. Protease-activated receptor 2 activation of myeloid dendritic cells regulates allergic airway inflammation. Respir. Res. 2011, 12, 122, doi:10.1186/1465-9921-12-122.Price, A.E.; Liang, H.E.; Sullivan, B.M.; Reinhardt, R.L.; Eisley, C.J.; Erle, D.J.; Locksley, R.M. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11489–11494, doi:10.1073/pnas.1003988107.

- Runswick, S.; Mitchell, T.; Davies, P.; Robinson, C.; Garrod, D.R. Pollen proteolytic enzymes degrade tight junctions. Respirology 2007, 12, 834–842, doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01175.x.Saenz, S.A.; Siracusa, M.C.; Perrigoue, J.G.; Spencer, S.P.; Urban, J.F.; Tocker, J.E.; Budelsky, A.L.; Kleinschek, M.A.; Kastelein, R.A.; Kambayashi, T.; et al. IL25 elicits a multipotent progenitor cell population that promotes T(H)2 cytokine responses. Nature 2010, 464, 1362–1366, doi:10.1038/nature08901.

- Sajjan, U.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Gruenert, D.C.; Hershenson, M.B. Rhinovirus disrupts the barrier function of polarized airway epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 1271–1281, doi:10.1164/rccm.200801-136OC.Barlow, J.L.; McKenzie, A.N. Type-2 innate lymphoid cells in human allergic disease. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 14, 397–403, doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000090.

- Comstock, A.T.; Ganesan, S.; Chattoraj, A.; Faris, A.N.; Margolis, B.J.; Hershenson, M.B.; Sajjan, U.S. Rhinovirus-induced barrier dysfunction in polarized airway epithelial cells is mediated by NADPH oxidase 1. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 6795–6808, doi:10.1128/JVI.02074-10. .Chang, J.E.; Doherty, T.A.; Baum, R.; Broide, D. Prostaglandin D2 regulates human type 2 innate lymphoid cell chemotaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 899–901, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.020.

- Schamberger, A.C.; Mise, N.; Jia, J.; Genoyer, E.; Yildirim, A.O.; Meiners, S.; Eickelberg, O. Cigarette smoke-induced disruption of bronchial epithelial tight junctions is prevented by transforming growth factor-beta. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 50, 1040–1052, doi:10.1165/rcmb.2013-0090OC.Lewkowich, I.P.; Day, S.B.; Ledford, J.R.; Zhou, P.; Dienger, K.; Wills-Karp, M.; Page, K. Protease-activated receptor 2 activation of myeloid dendritic cells regulates allergic airway inflammation. Respir. Res. 2011, 12, 122, doi:10.1186/1465-9921-12-122.

- Bayram, H.; Rusznak, C.; Khair, O.A.; Sapsford, R.J.; Abdelaziz, M.M. Effect of ozone and nitrogen dioxide on the permeability of bronchial epithelial cell cultures of non-asthmatic and asthmatic subjects. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2002, 32, 1285–1292, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.01435.x.Runswick, S.; Mitchell, T.; Davies, P.; Robinson, C.; Garrod, D.R. Pollen proteolytic enzymes degrade tight junctions. Respirology 2007, 12, 834–842, doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01175.x.

- Lehmann, A.D.; Blank, F.; Baum, O.; Gehr, P.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.M. Diesel exhaust particles modulate the tight junction protein occludin in lung cells in vitro. Part. Fibre. Toxicol. 2009, 6, 26, doi:10.1186/1743-8977-6-26.Sajjan, U.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Gruenert, D.C.; Hershenson, M.B. Rhinovirus disrupts the barrier function of polarized airway epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 1271–1281, doi:10.1164/rccm.200801-136OC.

- van Vliet, S.J.; den Dunnen, J.; Gringhuis, S.I.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.; van Kooyk, Y. Innate signaling and regulation of Dendritic cell immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2007, 19, 435–440, doi:10.1016/j.coi.2007.05.006.Comstock, A.T.; Ganesan, S.; Chattoraj, A.; Faris, A.N.; Margolis, B.J.; Hershenson, M.B.; Sajjan, U.S. Rhinovirus-induced barrier dysfunction in polarized airway epithelial cells is mediated by NADPH oxidase 1. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 6795–6808, doi:10.1128/JVI.02074-10. .

- Vroling, A.B.; Fokkens, W.J.; van Drunen, C.M. How epithelial cells detect danger: Aiding the immune response. Allergy 2008, 63, 1110–1123, doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01785.x.Schamberger, A.C.; Mise, N.; Jia, J.; Genoyer, E.; Yildirim, A.O.; Meiners, S.; Eickelberg, O. Cigarette smoke-induced disruption of bronchial epithelial tight junctions is prevented by transforming growth factor-beta. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 50, 1040–1052, doi:10.1165/rcmb.2013-0090OC.

- Eisenbarth, S.C. Dendritic cell subsets in T cell programming: Location dictates function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 89–103, doi:10.1038/s41577-018-0088-1.Bayram, H.; Rusznak, C.; Khair, O.A.; Sapsford, R.J.; Abdelaziz, M.M. Effect of ozone and nitrogen dioxide on the permeability of bronchial epithelial cell cultures of non-asthmatic and asthmatic subjects. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2002, 32, 1285–1292, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.01435.x.

- Stone, K.D.; Prussin, C.; Metcalfe, D.D. IgE, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, 73–80, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.017.Lehmann, A.D.; Blank, F.; Baum, O.; Gehr, P.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.M. Diesel exhaust particles modulate the tight junction protein occludin in lung cells in vitro. Part. Fibre. Toxicol. 2009, 6, 26, doi:10.1186/1743-8977-6-26.

- Halim, T.Y.F.; Hwang, Y.Y.; Scanlon, S.T.; Zaghouani, H.; Garbi, N.; Fallon, P.G.; McKenzie, A.N.J. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells license dendritic cells to potentiate memory T helper 2 cell responses. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 57–64, doi:10.1038/ni.3294.van Vliet, S.J.; den Dunnen, J.; Gringhuis, S.I.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.; van Kooyk, Y. Innate signaling and regulation of Dendritic cell immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2007, 19, 435–440, doi:10.1016/j.coi.2007.05.006.

- Guilliams, M.; Dutertre, C.A.; Scott, C.L.; McGovern, N.; Sichien, D.; Chakarov, S.; Van Gassen, S.; Chen, J.; Poidinger, M.; De Prijck, S.; et al. Unsupervised high-dimensional analysis aligns dendritic cells across tissues and species. Immunity 2016, 45, 669–684, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.015.Vroling, A.B.; Fokkens, W.J.; van Drunen, C.M. How epithelial cells detect danger: Aiding the immune response. Allergy 2008, 63, 1110–1123, doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01785.x.

- Guilliams, M.; Ginhoux, F.; Jakubzick, C.; Naik, S.H.; Onai, N.; Schraml, B.U.; Segura, E.; Tussiwand, R.; Yona, S. Dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages: A unified nomenclature based on ontogeny. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 571–578, doi:10.1038/nri3712.Eisenbarth, S.C. Dendritic cell subsets in T cell programming: Location dictates function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 89–103, doi:10.1038/s41577-018-0088-1.

- Sung, S.S.; Fu, S.M.; Rose, C.E.; Gaskin, F.; Ju, S.T.; Beaty, S.R. A major lung CD103 (alphaE)-beta7 integrin-positive epithelial dendritic cell population expresSing Langerin and tight junction proteins. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 2161–2172, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2161.Stone, K.D.; Prussin, C.; Metcalfe, D.D. IgE, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, 73–80, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.017.

- von Garnier, C.; Filgueira, L.; Wikstrom, M.; Smith, M.; Thomas, J.A.; Strickland, D.H.; Holt, P.G.; Stumbles, P.A. Anatomical location determines the distribution and function of dendritic cells and other APCs in the respiratory tract. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 1609–1618, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1609.Halim, T.Y.F.; Hwang, Y.Y.; Scanlon, S.T.; Zaghouani, H.; Garbi, N.; Fallon, P.G.; McKenzie, A.N.J. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells license dendritic cells to potentiate memory T helper 2 cell responses. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 57–64, doi:10.1038/ni.3294.

- Thornton, E.E.; Looney, M.R.; Bose, O.; Sen, D.; Sheppard, D.; Locksley, R.; Huang, X.; Krummel, M.F. Spatiotemporally separated antigen uptake by alveolar dendritic cells and airway presentation to T cells in the lung. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 1183–1199, doi:10.1084/jem.20112667.Guilliams, M.; Dutertre, C.A.; Scott, C.L.; McGovern, N.; Sichien, D.; Chakarov, S.; Van Gassen, S.; Chen, J.; Poidinger, M.; De Prijck, S.; et al. Unsupervised high-dimensional analysis aligns dendritic cells across tissues and species. Immunity 2016, 45, 669–684, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.015.

- Asselin-Paturel, C.; Boonstra, A.; Dalod, M.; Durand, I.; Yessaad, N.; Dezutter-Dambuyant, C.; Vicari, A.; O’Garra, A.; Biron, C.; Brière, F.; et al. Mouse type I IFN-producing cells are immature APCs with plasmacytoid morphology. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 1144–1150, doi:10.1038/ni736.Guilliams, M.; Ginhoux, F.; Jakubzick, C.; Naik, S.H.; Onai, N.; Schraml, B.U.; Segura, E.; Tussiwand, R.; Yona, S. Dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages: A unified nomenclature based on ontogeny. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 571–578, doi:10.1038/nri3712.

- Gill, M.A. The role of dendritic cells in asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, 889–901, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.028.Sung, S.S.; Fu, S.M.; Rose, C.E.; Gaskin, F.; Ju, S.T.; Beaty, S.R. A major lung CD103 (alphaE)-beta7 integrin-positive epithelial dendritic cell population expresSing Langerin and tight junction proteins. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 2161–2172, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2161.

- Veres, T.Z.; Voedisch, S.; Spies, E.; Valtonen, J.; Prenzler, F.; Braun, A. Aeroallergen challenge promotes dendritic cell proliferation in the airways. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 897–903, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1200220.von Garnier, C.; Filgueira, L.; Wikstrom, M.; Smith, M.; Thomas, J.A.; Strickland, D.H.; Holt, P.G.; Stumbles, P.A. Anatomical location determines the distribution and function of dendritic cells and other APCs in the respiratory tract. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 1609–1618, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1609.

- Xu, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Lew, A.M.; Naik, S.H.; Kershaw, M.H. Differential development of murine dendritic cells by GM-CSF versus Flt3 ligand has implications for inflammation and trafficking. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 7577–7584, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7577.Thornton, E.E.; Looney, M.R.; Bose, O.; Sen, D.; Sheppard, D.; Locksley, R.; Huang, X.; Krummel, M.F. Spatiotemporally separated antigen uptake by alveolar dendritic cells and airway presentation to T cells in the lung. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 1183–1199, doi:10.1084/jem.20112667.

- Greer, A.M.; Matthay, M.A.; Kukreja, J.; Bhakta, N.R.; Nguyen, C.P.; Wolters, P.J.; Woodruff, P.G.; Fahy, J.V.; Shin, J.S. Accumulation of BDCA1(+) dendritic cells in interstitial fibrotic lung diseases and Th2-high asthma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99084, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099084.Asselin-Paturel, C.; Boonstra, A.; Dalod, M.; Durand, I.; Yessaad, N.; Dezutter-Dambuyant, C.; Vicari, A.; O’Garra, A.; Biron, C.; Brière, F.; et al. Mouse type I IFN-producing cells are immature APCs with plasmacytoid morphology. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 1144–1150, doi:10.1038/ni736.

- Villani, A.-C.; Satija, R.; Reynolds, G.; Sarkizova, S.; Shekhar, K.; Fletcher, J.; Griesbeck, M.; Butler, A.; Zheng, S.; Lazo, S.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science 2017, 356, 6335, doi:10.1126/science.aah4573.Gill, M.A. The role of dendritic cells in asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, 889–901, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.028.

- Calzetti, F.; Tamassia, N.; Micheletti, A.; Finotti, G.; Bianchetto-Aguilera, F.; Cassatella, M.A. Human dendritic cell subset 4 (DC4) correlates to a subset of CD14dim/-CD16++ monocytes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 2276–2279.e3, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.988.Veres, T.Z.; Voedisch, S.; Spies, E.; Valtonen, J.; Prenzler, F.; Braun, A. Aeroallergen challenge promotes dendritic cell proliferation in the airways. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 897–903, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1200220.

- Hayashi, Y.; Ishii, Y.; Hata-Suzuki, M.; Arai, R.; Chibana, K.; Takemasa, A.; Fukuda, T. Comparative analysis of circulating dendritic cell subsets in patients with atopic diseases and sarcoidosis. Respir. Res. 2013, 14, 29, doi:10.1186/1465-9921-14-29.Xu, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Lew, A.M.; Naik, S.H.; Kershaw, M.H. Differential development of murine dendritic cells by GM-CSF versus Flt3 ligand has implications for inflammation and trafficking. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 7577–7584, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7577.

- Dua, B.; Watson, R.M.; Gauvreau, G.M.; O’Byrne, P.M. Myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in induced sputum after allergen inhalation in subjects with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, 133–139, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.006.Greer, A.M.; Matthay, M.A.; Kukreja, J.; Bhakta, N.R.; Nguyen, C.P.; Wolters, P.J.; Woodruff, P.G.; Fahy, J.V.; Shin, J.S. Accumulation of BDCA1(+) dendritic cells in interstitial fibrotic lung diseases and Th2-high asthma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99084, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099084.

- Dua, B.; Tang, W.; Watson, R.; Gauvreau, G.; O’Byrne, P.M. Myeloid dendritic cells type 2 after allergen inhalation in asthmatic subjects. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2014, 44, 921–929, doi:10.1111/cea.12297.Villani, A.-C.; Satija, R.; Reynolds, G.; Sarkizova, S.; Shekhar, K.; Fletcher, J.; Griesbeck, M.; Butler, A.; Zheng, S.; Lazo, S.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science 2017, 356, 6335, doi:10.1126/science.aah4573.

- El-Gammal, A.; Oliveria, J.P.; Howie, K.; Watson, R.; Mitchell, P.; Chen, R.; Baatjes, A.; Smith, S.; Al-Sajee, D.; Hawke, T.J.; et al. Allergen-induced changes in bone marrow and airway dendritic cells in subjects with asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 194, 169–177, doi:10.1164/rccm.201508-1623OC.Calzetti, F.; Tamassia, N.; Micheletti, A.; Finotti, G.; Bianchetto-Aguilera, F.; Cassatella, M.A. Human dendritic cell subset 4 (DC4) correlates to a subset of CD14dim/-CD16++ monocytes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 2276–2279.e3, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.988.

- Sharquie, I.K.; Al-Ghouleh, A.; Fitton, P.; Clark, M.R.; Armour, K.L.; Sewell, H.F.; Shakib, F.; Ghaemmaghami, A.M. An investigation into IgE-facilitated allergen recognition and presentation by human dendritic cells. BMC Immunol. 2013, 14, 54, doi:10.1186/1471-2172-14-54.van Rijt, L.S.; Jung, S.; Kleinjan, A.; Vos, N.; Willart, M.; Duez, C.; Hoogsteden, H.C.; Lambrecht, B.N. In vivo depletion of lung CD11c+ dendritic cells during allergen challenge abrogates the characteristic features of asthma. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 981–991, doi:10.1084/jem.20042311.

- Froidure, A.; Shen, C.; Gras, D.; Van Snick, J.; Chanez, P.; Pilette, C. Myeloid dendritic cells are primed in allergic asthma for thymic stromal lymphopoietin-mediated induction of Th2 and Th9 responses. Allergy 2014, 69, 1068–1076, doi:10.1111/all.12435.Vroman, H.; Hendriks, R.W.; Kool, M. Dendritic Cell Subsets in Asthma: Impaired Tolerance or Exaggerated Inflammation? Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 941, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00941.

- Spears, M.; McSharry, C.; Donnelly, I.; Jolly, L.; Brannigan, M.; Thomson, J.; Lafferty, J.; Chaudhuri, R.; Shepherd, M.; Cameron, E.; et al. Peripheral blood dendritic cell subtypes are significantly elevated in subjects with asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2011, 41, 665–672, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03692.x.Plantinga, M.; Guilliams, M.; Vanheerswynghels, M.; Deswarte, K.; Branco-Madeira, F.; Toussaint, W.; Vanhoutte, L.; Neyt, K.; Killeen, N.; Malissen, B.; et al. Conventional and monocyte-derived CD11b+ dendritic cells initiate and maintain T helper 2 cell-mediated immunity to house dust mite allergen. Immunity 2013, 38, 322–335, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.016.

- Wright, A.K.; Mistry, V.; Richardson, M.; Shelley, M.; Thornton, T.; Terry, S.; Barker, B.; Bafadhel, M.; Brightling, C. Toll-like receptor 9 dependent interferon-alpha release is impaired in severe asthma but is not associated with exacerbation frequency. Immunobiology 2015, 220, 859–864, doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2015.01.005.Ho, A.W.; Prabhu, N.; Betts, R.J.; Ge, M.Q.; Dai, X.; Hutchinson, P.E.; Lew, F.C.; Wong, K.L.; Hanson, B.J.; Macary, P.A.; et al. Lung CD103+ dendritic cells efficiently transport influenza virus to the lymph node and load viral antigen onto MHC class I for presentation to CD8 T cells. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 6011–6021, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1100987.

- Bratke, K.; Lommatzsch, M.; Julius, P.; Kuepper, M.; Kleine, H.D.; Luttmann, W.; Virchow, J.C. Dendritic cell subsets in human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after segmental allergen challenge. Thorax 2007, 62, 168–175, doi:10.1136/thx.2006.067793.Nakano, H.; Free, M.E.; Whitehead, G.S.; Maruoka, S.; Wilson, R.H.; Nakano, K.; Cook, D.N. Pulmonary CD103(+) dendritic cells prime Th2 responses to inhaled allergens. Mucosal. Immunol. 2012, 5, 53–65, doi:10.1038/mi.2011.47.

- Upham, J.W.; Zhang, G.; Rate, A.; Yerkovich, S.T.; Kusel, M.; Sly, P.D.; Holt, P.G. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells during infancy are inversely associated with childhood respiratory tract infections and wheezing. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 124, 707–713, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.009.Fear, V.S.; Lai, S.P.; Zosky, G.R.; Perks, K.L.; Gorman, S.; Blank, F.; von Garnier, C.; Stumbles, P.A.; Strickland, D.H. A pathogenic role for the integrin CD103 in experimental allergic airways disease. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 4, e13021, doi:10.14814/phy2.13021.

- Hammad. H.; Charbonnier, A.S.; Duez, C.; Jacquet, A.; Stewart, G.A.; Tonnel, A.B.; Pestel, J. Th2 polarization by Der p 1—Pulsed monocyte-derived dendritic cells is due to the allergic status of the donors. Blood 2001, 98, 1135–1141, doi:10.1182/blood.V98.4.1135.Furuhashi, K.; Suda, T.; Hasegawa, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Hashimoto, D.; Enomoto, N.; Fujisawa, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Inui, I.; Shibata, K.; et al. Mouse lung CD103+ and CD11bhigh dendritic cells preferentially induce distinct CD4+ T-cell responses. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 46, 165–172, doi:10.1165/rcmb.2011-0070OC.

- Geurts van Kessel, C.H.; Lambrecht, B.N. Division of labor between dendritic cell subsets of the lung. Mucosal Immunol. 2008, 1, 442–450, doi:10.1038/mi.2008.39.Raymond, M.; Rubio, M.; Fortin, G.; Shalaby, K.H.; Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Sarfati, M. Selective control of SIRP-alpha-positive airway dendritic cell trafficking through CD47 is critical for the development of T(H)2-mediated allergic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 124, 1333–1242, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.021.

- Worbs, T.; Hammerschmidt, S.I.; Förster, R. Dendritic cell migration in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 30–48, doi:10.1038/nri.2016.Norimoto, A.; Hirose, K.; Iwata, A.; Tamachi, T.; Yokota, M.; Takahashi, K.; Saijo, S.; Iwakura, Y.; Nakajima, H. Dectin-2 promotes house dust mite-induced T helper type 2 and type 17 cell differentiation and allergic airway inflammation in mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 51, 201–209, doi:10.1165/rcmb.2013-0522OC.

- Khare, A.; Krishnamoorthy, N.; Oriss, T.B.; Fei, M.; Ray, P.; Ray, A. Cutting edge: Inhaled antigen upregulates retinaldehyde dehydrogenase in lung CD103+ but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells to induce Foxp3 de novo in CD4+ T cells and promote airway tolerance. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 25–29, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1300193.Mishra, A.; Brown, A.L.; Yao, X.; Yang, S.; Park, S.J.; Liu, C.; Dagur, P.K.; McCoy, J.P.; Keeran, K.J.; Nugent, G.Z.; et al. Dendritic cells induce Th2-mediated airway inflammatory responses to house dust mite via DNA-dependent protein kinase. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6224, doi:10.1038/ncomms7224.

- Bernatchez, E.; Gold, M.J.; Langlois, A.; Lemay, A.M.; Brassard, J.; Flamand, N.; Marsolais, D.; McNagny, K.M.; Blanchet, M.R. Pulmonary CD103 expression regulates airway inflammation in asthma. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2015, 308, L816–826, doi:10.1152/ajplung.00319.2014.Medoff, B.D.; Seung, E.; Hong, S.; Thomas, S.Y.; Sandall, B.P.; Duffield, J.S.; Kuperman, D.A.; Erle, D.J.; Luster, A.D. CD11b+ myeloid cells are the key mediators of Th2 cell homing into the airway in allergic inflammation. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 623–635, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.623.

- Conejero, L.; Khouili, S.C.; Martínez-Cano, S.; Izquierdo, H.M.; Brandi, P.; Sancho, D. Lung CD103+ dendritic cells restrain allergic airway inflammation through IL-12 production. JCI Insight 2017, 2, 90420, doi:10.1172/jci.insight.90420.Lewkowich, I.P.; Lajoie, S.; Clark, J.R.; Herman, N.S.; Sproles, A.A.; Wills-Karp, M. Allergen uptake, activation, and IL-23 production by pulmonary myeloid DCs drives airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma-susceptible mice. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3879, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003879.

- Engler, D.B.; Reuter, S.; van Wijck, Y.; Urban, S.; Kyburz, A.; Maxeiner, J.; Martin, H.; Yogev, N.; Waisman, A.; Gerhard, M.; et al. Effective treatment of allergic airway inflammation with Helicobacter pylori immunomodulators requires BATF3-dependent dendritic cells and IL-10. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 11810–11815, doi:10.1073/pnas.1410579111.Kool, M.; Geurtsvankessel, C.; Muskens, F.; Madeira, F.B.; van Nimwegen, M.; Kuipers, H.; Thielemans, K.; Hoogsteden, H.C.; Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N. Facilitated antigen uptake and timed exposure to TLR ligands dictate the antigen-presenting potential of plasmacytoid DCs. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2011, 90, 1177–1190, doi:10.1189/jlb.0610342.

- Oriss, T.B.; Ostroukhova, M.; Seguin-Devaux, C.; Dixon-McCarthy, B.; Stolz, D.B.; Watkins, S.C.; Pillemer, B.; Ray, P.; Ray, A. Dynamics of dendritic cell phenotype and interactions with CD4+ T cells in airway inflammation and tolerance. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 854–863, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.854.Lombardi, V.; Speak, A.O.; Kerzerho, J.; Szely, N.; Akbari, O. CD8alpha(+)beta(-) and CD8alpha(+)beta(+) plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells and prevent the induction of airway hyper-reactivity. Mucosal Immunol. 2012, 5, 432–443, doi:10.1038/mi.2012.20.

- Lewkowich, I.P.; Herman, N.S.; Schleifer, K.W.; Dance, M.P.; Chen, B.L.; Dienger, K.M.; Sproles, A.A.; Shah, J.S.; Köhl, J.; Belkaid, Y.; et al. CD4+CD25+ T cells protect against experimentally induced asthma and alter pulmonary dendritic cell phenotype and function. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 202, 1549–1561, doi:10.1084/jem.20051506.Hayashi, Y.; Ishii, Y.; Hata-Suzuki, M.; Arai, R.; Chibana, K.; Takemasa, A.; Fukuda, T. Comparative analysis of circulating dendritic cell subsets in patients with atopic diseases and sarcoidosis. Respir. Res. 2013, 14, 29, doi:10.1186/1465-9921-14-29.

- de Heer, H.J.; Hammad, H.; Soullié, T. Essential role of lung plasmacytoid dendritic cells in preventing asthmatic reactions to harmless inhaled antigen. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 200, 89–98, doi:10.1084/jem.20040035.Dua, B.; Watson, R.M.; Gauvreau, G.M.; O’Byrne, P.M. Myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in induced sputum after allergen inhalation in subjects with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, 133–139, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.006.

- Kool, M.; van Nimwegen, M.; Willart, M.A.; Muskens, F.; Boon, L.; Smit, J.J.; Coyle, A.; Clausen, B.J..; Hoogsteden, H.C.; Lambrecht, B.N.; et al. An anti-inflammatory role for plasmacytoid dendritic cells in allergic airway inflammation. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 1074–1082, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0900471.Dua, B.; Tang, W.; Watson, R.; Gauvreau, G.; O’Byrne, P.M. Myeloid dendritic cells type 2 after allergen inhalation in asthmatic subjects. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2014, 44, 921–929, doi:10.1111/cea.12297.

- Lombardi, V.; Speak, A.O.; Kerzerho, J.; Szely, N.; Akbari, O. CD8alpha(+)beta(-) and CD8alpha(+)beta(+) plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells and prevent the induction of airway hyper-reactivity. Mucosal Immunol. 2012, 5, 432–443, doi:10.1038/mi.2012.20.El-Gammal, A.; Oliveria, J.P.; Howie, K.; Watson, R.; Mitchell, P.; Chen, R.; Baatjes, A.; Smith, S.; Al-Sajee, D.; Hawke, T.J.; et al. Allergen-induced changes in bone marrow and airway dendritic cells in subjects with asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 194, 169–177, doi:10.1164/rccm.201508-1623OC.

- Chairakaki, A.D.; Saridaki, M.I.; Pyrillou, K.; Mouratis, M.A.; Koltsida, O.; Walton, R.P.; Bartlett, N.W.; Stavropoulos, A.; Boon, L.; Rovina, N.; et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells drive acute asthma exacerbations. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 542–556.e12, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.032.Sharquie, I.K.; Al-Ghouleh, A.; Fitton, P.; Clark, M.R.; Armour, K.L.; Sewell, H.F.; Shakib, F.; Ghaemmaghami, A.M. An investigation into IgE-facilitated allergen recognition and presentation by human dendritic cells. BMC Immunol. 2013, 14, 54, doi:10.1186/1471-2172-14-54.

- Kucuksezer, U.C.; Ozdemir, C.; Cevhertas, L.; Ogulur, I.; Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy and allergen tolerance. Allergol. Int. 2020, 69, 549–560, doi:10.1016/j.alit.2020.08.002.Froidure, A.; Shen, C.; Gras, D.; Van Snick, J.; Chanez, P.; Pilette, C. Myeloid dendritic cells are primed in allergic asthma for thymic stromal lymphopoietin-mediated induction of Th2 and Th9 responses. Allergy 2014, 69, 1068–1076, doi:10.1111/all.12435.

- Bellinghausen, I.; Brand, U.; Steinbrink, K.; Enk, A.H.; Knop, J.; Saloga, J. Inhibition of human allergic T-cell responses by IL-10-treated dendritic cells: Differences from hydrocortisone-treated dendritic cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001, 108, 242–249, doi:10.1067/mai.2001.117177.Spears, M.; McSharry, C.; Donnelly, I.; Jolly, L.; Brannigan, M.; Thomson, J.; Lafferty, J.; Chaudhuri, R.; Shepherd, M.; Cameron, E.; et al. Peripheral blood dendritic cell subtypes are significantly elevated in subjects with asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2011, 41, 665–672, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03692.x.

- Escobar, A.; Aguirre, A.; Guzmán, M.A.; González, R.; Catalán, D.; Acuña-Castillo, C.; Larrondo, M.; López, M.; Pesce, B.; Rolland, J.; et al. Tolerogenic dendritic cells derived from donors with natural rubber latex allergy modulate allergen-specific T-cell responses and IgE production. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85930, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085930.Wright, A.K.; Mistry, V.; Richardson, M.; Shelley, M.; Thornton, T.; Terry, S.; Barker, B.; Bafadhel, M.; Brightling, C. Toll-like receptor 9 dependent interferon-alpha release is impaired in severe asthma but is not associated with exacerbation frequency. Immunobiology 2015, 220, 859–864, doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2015.01.005.

- Bratke, K.; Lommatzsch, M.; Julius, P.; Kuepper, M.; Kleine, H.D.; Luttmann, W.; Virchow, J.C. Dendritic cell subsets in human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after segmental allergen challenge. Thorax 2007, 62, 168–175, doi:10.1136/thx.2006.067793.

- Upham, J.W.; Zhang, G.; Rate, A.; Yerkovich, S.T.; Kusel, M.; Sly, P.D.; Holt, P.G. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells during infancy are inversely associated with childhood respiratory tract infections and wheezing. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 124, 707–713, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.009.

- Hammad. H.; Charbonnier, A.S.; Duez, C.; Jacquet, A.; Stewart, G.A.; Tonnel, A.B.; Pestel, J. Th2 polarization by Der p 1—Pulsed monocyte-derived dendritic cells is due to the allergic status of the donors. Blood 2001, 98, 1135–1141, doi:10.1182/blood.V98.4.1135.

- Geurts van Kessel, C.H.; Lambrecht, B.N. Division of labor between dendritic cell subsets of the lung. Mucosal Immunol. 2008, 1, 442–450, doi:10.1038/mi.2008.39.

- Worbs, T.; Hammerschmidt, S.I.; Förster, R. Dendritic cell migration in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 30–48, doi:10.1038/nri.2016.

- Khare, A.; Krishnamoorthy, N.; Oriss, T.B.; Fei, M.; Ray, P.; Ray, A. Cutting edge: Inhaled antigen upregulates retinaldehyde dehydrogenase in lung CD103+ but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells to induce Foxp3 de novo in CD4+ T cells and promote airway tolerance. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 25–29, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1300193.

- Bernatchez, E.; Gold, M.J.; Langlois, A.; Lemay, A.M.; Brassard, J.; Flamand, N.; Marsolais, D.; McNagny, K.M.; Blanchet, M.R. Pulmonary CD103 expression regulates airway inflammation in asthma. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2015, 308, L816–826, doi:10.1152/ajplung.00319.2014.

- Conejero, L.; Khouili, S.C.; Martínez-Cano, S.; Izquierdo, H.M.; Brandi, P.; Sancho, D. Lung CD103+ dendritic cells restrain allergic airway inflammation through IL-12 production. JCI Insight 2017, 2, 90420, doi:10.1172/jci.insight.90420.

- Engler, D.B.; Reuter, S.; van Wijck, Y.; Urban, S.; Kyburz, A.; Maxeiner, J.; Martin, H.; Yogev, N.; Waisman, A.; Gerhard, M.; et al. Effective treatment of allergic airway inflammation with Helicobacter pylori immunomodulators requires BATF3-dependent dendritic cells and IL-10. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 11810–11815, doi:10.1073/pnas.1410579111.

- Koya, T.; Matsuda, H.; Takeda, K.; Matsubara, S.; Miyahara, N.; Balhorn, A.; Dakhama, A.; Gelfand, E.W. IL-10-treated dendritic cells decrease airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation in mice. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 119, 1241–1250, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.039.

- Huang, H.; Dawicki, W.; Lu, M.; Nayyar, A.; Zhang, X.; Gordon, J.R. Regulatory dendritic cell expression of MHCII and IL-10 are jointly requisite for induction of tolerance in a murine model of OVA-asthma. Allergy 2013, 68, 1126–1135, doi:10.1111/all.1220.

- Fujita, S.; Yamashita, N.; Ishii, Y.; Sato, Y.; Sato, K.; Eizumi, K.; Fukaya, T.; Nozawa, R.; Takamoto, Y.; Yamashita, N.; et al. Regulatory dendritic cells protect against allergic airway inflammation in a murine asthmatic model. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 121, 95–104.e7, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.038.

- Lu, M.; Dawicki, W.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Nayyar, A.; Gordon, J.R. Therapeutic induction of tolerance by IL-10-differentiated dendritic cells in a mouse model of house dust mite-asthma. Allergy 2011, 66, 612–620, doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02526.x.