Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Valentina Cazzetta and Version 2 by Dean Liu.

Targeting NKG2A immune checkpoint by gene knockout or blocking antibodies improves the cytotoxicity of Vδ2 T cells, a specific subset of human unconventional γδ T lymphocytes. Thus, a suitable selection of NKG2A+ or NKG2A− Vδ2 T cells for expansion or engineering could help to narrow the Vδ2 T cell population according to the expression of HLA-E on tumor cells. With this emerging knowledge, approaches to target NKG2A in Vδ2 T cells might be a promising step forward to boosting Vδ2 T cell-based cancer immunotherapies.

- γδ T cells

- NKG2A

- inhibitory receptors

- immune checkpoint inhibitors

1. Introduction

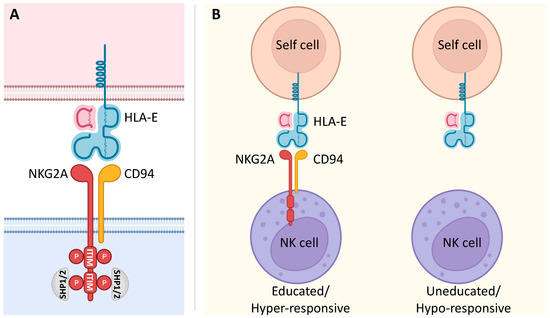

NKG2A is a member of the C-type lectin receptors for MHC class I and is encoded by the gene complex located within the Natural Killer (NK) complex (NKC) on human chromosome 12p12-13. This gene complex varies in gene content between species and can encode both activating and inhibitory polymorphic receptors [1][21]. In humans, KLRC1 is one of four functional killer cell lectin-like receptor KLRC genes (NKG2A, C, E, and F) that, together with KLRD1 (CD94), form a heterodimeric NKG2A/CD94 inhibitory receptor (Figure 1A) [2][22]. NKG2A is a single-pass type II integral membrane glycoprotein that contains cytoplasmic, transmembrane, and extracellular lectin-like domains [3][23]. The intracellular portion has two immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs (ITIMs), whose phosphorylation recruits the intracellular phosphatases SHP-1 and -2 and induces an inhibitory signal upon binding to its ligand, the non-classical class I human leukocyte antigen E (HLA-E) [4][5][6][7][24,25,26,27]. The expression of NKG2A was detected in cytotoxic lymphocytes, including most NK cells, type 1 innate lymphocytes (ILC1), unconventional NKT cells, different subsets of CD8 αβ T and γδ T cells, specifically on Vδ2 T cell subset, in which its inhibitory signal suppresses their activation and its blocking can effectively unleash their effector response [8][9][10][11][12][13][28,29,30,31,32,33].

Figure 1. NKG2A signaling and its involvement in NK cell education. (A) The C-type lectin NKG2A receptor forms a heterodimer with CD94. It is characterized by a long cytoplasmic domain that contains two ITIMs. Upon binding to its ligand, inhibitory signaling of the non-classical MHC class I molecule HLA-E is based on the phosphorylation of two ITIMs with the consequent recruitment of the intracellular phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2. (B) NKG2A is known to be involved in NK cell education. In fact, the interaction of NKG2A with its ligand HLA-E renders NK cells educated and hyper-responsive, setting their effector functions at higher levels in response to stimulatory activation. On the other hand, NK cells that fail this interaction due to the lack of NKG2A are uneducated and hypo-responsive.

HLA-E, the ligand of NKG2A, is lowly expressed on almost all cell surfaces in human tissues, displays limited polymorphism, and presents peptides derived from the leader sequences of the classical MHC class I molecules HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C [14][15][34,35]. Thus, the expression of HLA-E is directly related to the number of HLA-I molecules in a given cell, and NKG2A acts as a sensor to assess the net overall expression of HLA-I molecules on a target cell. Importantly, the expression of HLA-E greatly increases in several human malignancies with consequent inhibition of the effector functions of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) through its binding with NKG2A [16][36]. This interaction between NKG2A and HLA-E contributes to tumor immune escape; therefore, NKG2A-mediated mechanisms are currently being exploited to develop potential anti-tumor therapeutic strategies [10][14][17][30,34,37].

2. Impact of NKG2A on the Effector Potential of Vδ2 T Cells

The earliest remark on the expression of NKG2A in human γδ T cells dates back to 1997 and shows that human γδ T cells, mostly Vδ2 T cells, harbor the CD94/NKG2A heterodimer [18][19][120,121]. Although this analysis was performed on a limited number of peripheral blood samples of healthy adults, our and other studies have confirmed these results by performing extensive multiparametric flow cytometry analyses on a vast number of analyzed samples [9][20][29,122]. NKG2A shows a high range of expression among Vδ2 T cells which, in healthy adults, covers from 20% to 90% of cells with a median of 50%, independently of age and gender. This high expression of NKG2A by Vδ2 T cells was further confirmed by transcriptional analysis [9][21][22][29,123,124]. On the other hand, low expression levels of NKG2A were observed in Vδ1 and Vδ3 T cells in the blood and in the liver tissue where these cells preferably reside [18][21][22][23][24][15,17,120,123,124]. Differently, NKG2C, which also binds HLA-E, although with a 6-fold lower affinity [25][125], is rarely expressed on Vδ2 T cells [9][20][29,122]. NKG2A plays a key role in the development of NK cells. In fact, theour current knowledge on the development of NK cells states that NKG2A is the only HLA-specific inhibitory receptor expressed on the precursor CD56bright cell subset of human NK cells, and its expression gradually diminishes on the mature CD56dim NK cell subset [10][26][30,126]. Additionally, reconstitution of NK cells following allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) demonstrated that circulating NK cells present a transient phenotype of CD56dim cells expressing high levels of NKG2A that is progressively lost over time, thus implying NKG2A an important receptor for early stages of NK cell ontogenesis [27][127]. Instead, the role of NKG2A in the ontogeny of human γδ T cells is not defined yet. Interestingly, our and other studies indicate that the expression of this inhibitory receptor on Vδ2 T cells is already programmed in the postnatal pediatric thymus and can be detected in the blood soon after birth (within 10 weeks) [9][28][29][29,128,129]. On the other hand, neither the expression of NKG2A nor that of CD94 has been detected in cord blood [20][29][122,129]. The absence of CD94 in Vδ2 T cells in neonates and infants is not due to a generalized lack of CD94 expression, as NK cells express a level of CD94 that is comparable to that of adult NK cells [20][122]. This suggests that the acquisition of NKG2A could be triggered by the postnatal thymus environment and, once these cells are in the periphery, their concentration can expand in response to environmental and pathogenic microbes, resulting in the predominance of Vδ2 T cells in the majority of the adult population. Little is also known about the possible regulation of NKG2A expression in adults. The expression of NKG2A in Vδ2 T cells expanded in vitro does not increase upon PhAgs and IL-2 activation. Indeed, an unrelated in vitro expansion of NKG2A+ and NKG2A− Vδ2 T cells was observed, suggesting the autonomous self-renewal of these two subpopulations [9][29]. In adults, NKG2A+ and NKG2A− Vδ2 T cells show few phenotypical differences at both the protein and transcriptional levels, resulting in similarities in differentiation status and clonal expansion [9][29]. Moreover, differently from CD8 αβ T cells, in which the expression of NKG2A is induced during viral infections such as human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) [30][130], in γδ T cells, HCMV infection does not seem to impact the expression of NKG2A [9][29]. However, further studies are necessary to understand their possible roles in viral infections. Importantly, minor phenotypic differences are offset by an evident functional divergency between NKG2A+ and NKG2A− Vδ2 T cells [9][22][29,124]. Indeed, researchwers and others have observed a paradigm whereby Vδ2 T cells harboring this negative receptor NKG2A are characterized by hyper-responsiveness [9][18][29,120]. Indeed, NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells produce significantly higher amounts of IFN-γ and TNF-α upon PhAg TCR activation. In addition, NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells present higher cytotoxic potential against HLA class I deficient tumor cell targets that do not express the NKG2A ligand, HLA-E. These data were also confirmed by transcriptional analysis at single-cell resolution, showing that Vδ2 T cells expressing NKG2A harbor a greater cytotoxic potential and ability to produce IFN-γ and TNF-α cytokines [9][20][21][31][29,48,122,123]. Interestingly, NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells require higher amounts of PhAgs to produce their maximal cell response [18][120], thus indicating that the CD94/NKG2A complex does not prevent the activation of Vδ2 T cells by their ligands but rather affects their activation thresholds. In this context, there is growing evidence of the role of NKG2A in the so-called “education” of NK cells [32][33][34][131,132,133]. This process is finely tuned by the interactions of inhibitory receptors with their ligands to set the effector functions of NK cells at hyper-responsive levels in response to stimulatory activation (Figure 1B). In the case of γδ T cells, it is still not clear whether the hyper-responsive NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells are “educated” or whether they represent more mature cells. In fact, the higher effector potential of NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells could be a consequence of both their education and their maturation process. However, the presence of highly differentiated and clonally expanded NKG2A+ and NKG2A− Vδ2 T cells in healthy adults indicates that the expression of NKG2A identifies a subset of Vδ2 T “educated” cells [9][31][29,48]. NK cell education primarily appears during cell development, although new findings suggest that this phenomenon also occurs under disease conditions [35][134]. The observed increase in the expression of NKG2A in postnatal γδ thymocytes indicates their possible educational process in the thymus early after birth [9][28][29][29,128,129]. These data are also in line with the observation that Vδ2 T cells acquire higher levels of cytotoxic mediators (e.g., granzymes, perforin, granulysin) in correlation with increased expression of NKG2A rapidly after birth [29][129]. In addition, it was observed that IL-23 drives in CD94− Vδ2 T cells the acquisition of a cytotoxic program and the CD94+ phenotype [20][122]. The mechanisms that drive the education of NK cells through NKG2A are poorly understood, but it has been reported that HLA-E expression is fundamental. In particular, genetic modifications that influence HLA-E expression have shown a correlation between NKG2A expression and NK cell education. In fact, cell membrane expression of HLA-E requires the supply of peptides from classical HLA-A, HLA-B, or HLA-C for appropriate folding and transport to the cell surface [36][135]. There is a dimorphism of the leader sequence supplied by HLA-B encoding either threonine (T) or methionine (M) [37][38][136,137]. This separates individuals into those who can provide functional peptides for high HLA-E expression and NKG2A ligation, which leads to education and increased functional potency (MT or MM), and those who cannot (TT) and therefore have low HLA-E expression [39][138]. A role for this HLA-B dimorphism is emerging in patients with leukemia and GvHD [40][41][139,140]. Thus, it could be interesting to evaluate whether the functional potency of γδ T cells might be influenced by HLA-B alleles. Overall, the expression of the NKG2A receptor defines distinct Vδ2 T cells with higher anti-tumor potential that may be useful for Vδ2 T-cell-based cancer immunotherapies. However, further studies are necessary to unveil the ability of NKG2A to enhance the cytotoxic potential of Vδ2 T cells. In this regard, several features of the human Vδ2 T cell compartment suggest similarities to mouse γδ T cell subsets [42][141]. Thus, it would be interesting to evaluate NKG2A expression in different subsets/effector-linage of murine γδ T cells. Indeed, recently the NKG2A knockout mouse model has been used to unveil the role of NKG2A in the education process of tissue-resident NK cells [34][133].3. NKG2A Immune Checkpoint in Vδ2 T Cells

The hyper-responsiveness of NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells can be counterbalanced by the inhibitory signaling of NKG2A upon binding with its HLA-E ligand, thus affirming that NKG2A is the crucial IC in Vδ2 T cells. Indeed, the CD94/NKG2A complex expressed on Vδ2 T cells is able to efficiently block the killing of tumor cells expressing HLA-E molecules [9][18][19][43][29,120,121,142]. In fact, masking with the monoclonal Ab (mAb) NKG2A/CD94 complex on Vδ2 T cells or MHC class I molecules on target cells increases the cytotoxic response of Vδ2 T cells to HLA-E-expressing tumor cells. Additionally, CRISPR/Cas9-induced NKG2A knockout in Vδ2 T cells activated and expanded in vitro enhances the killing of tumor cells, despite their HLA-E expression [9][29]. In addition, the cross-linking of NKG2A during CD3 stimulation reduces the cytotoxicity of Vδ2 T cells, confirming that NKG2A negatively regulates their cell function [20][122]. Although, in another study, no significant effect on the cytotoxic response of Vδ2 T cells was observed after CD94/NKG2A blocking with mAb. However, only two Vδ2 T cell clones, for which the expression level of NKG2A was not shown, were tested [44][143]. Overall, these results demonstrate that NKG2A is a functional IC in Vδ2 TILs and that the anti-tumor effector functions of NKG2A+ Vδ2 TILs are finely tuned by the degree of HLA-E expression on tumor target cells. Interestingly, the CD94/NKG2A complex on Vδ2 T cells also regulates both lytic and proliferative activities against virus-infected cells [19][121]. Indeed, triggering the mAb CD94 inhibitory signal in Vδ2 T cells significantly reduces the lysis of HIV- and HBV-infected targets. Accordingly, the masking of HLA class I molecules promotes the Vδ2 cytotoxicity of virus-infected targets. Moreover, an in vitro expansion of peripheral blood Vδ2 T is reduced upon CD94 triggering, which can otherwise be induced by HIV-infected cells [19][121]. The NKG2A receptor, which is highly expressed in human small intestinal γδ T IELs, was also found to negatively regulate CD8 αβ T IEL activation in celiac disease [45][144]. This suppression occurred partially as a result of the engagement of NKG2A with its ligand, HLA-E, on enterocytes and/or αβ T IELs. This immunosuppressive effect can be reduced by blocking the NKG2A/HLA-E interaction. Importantly, patients with active celiac disease have significantly decreased frequencies of NKG2A+ γδ T IELs, thus indicating that the NKG2A receptor expressed on γδ T IELs acts as a key regulator of celiac disease. Thus, physiologically, the expression of NKG2A on Vδ2 T interacts with ubiquitously expressed HLA-E, whose expression, although at low levels, on all nucleated cells may represent a mechanism to fine-tune functions of highly responsive NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells [46][47][145,146]. On the other hand, the overexpression of HLA-E in pathological conditions such as solid and hematological malignancies may be responsible for tumor escape from Vδ2 T cell-mediated immunosurveillance [48][147]. It is also possible that the increase of soluble HLA-E plasma levels found in some tumors may be responsible for the inhibition of Vδ2 T cells [49][50][148,149]. Since overexpressed HLA-E can prevent tumor cell lysis mediated by Vδ2 T cells, the blockade of the NKG2A-HLA-E axis may enhance the Vδ2 T cell-based immunotherapeutic efficacy by administering anti-NKG2A/CD94 mAb to unleash Vδ2 T effector functions. Furthermore, the differences in the anti-tumor potential of NKG2A+ and NKG2A− Vδ2 T provide functional indications of their potential uses and indicate the optimal choice according to the immunosuppressive HLA-E-mediated TME.4. NKG2A in Cancer Immunotherapy—The Use of Vδ2 T Cells

The overexpression of HLA-E is predictive of poor prognostic outcomes in patients with different tumors (e.g., OC, GBM, CRC, RCC, and NSCLC) [51][52][53][54][55][56][150,151,152,153,154,155]. According to multiple studies, having an increased number of NKG2A+ TILs is correlated with a poor prognosis in patients affected by colorectal, gynecological, breast, and liver cancers [50][53][57][58][59][60][149,152,156,157,158,159]. Collectively, this evidence indicates that it is worth developing NKG2A-HLA-E axis blockade strategies for immunotherapy in cancer patients. Monalizumab (IPH2201) is a humanized mAb that targets NKG2A [61][160]. When tested in preclinical studies, Monalizumab showed the capacity to enhance anti-tumor immunity by unleashing both NK cells and CD8 αβ T cells [62][161]. Andre et al. also showed that the combined blockade of NKG2A with Monalizumab in combination with PD-1/PD-L1 or Cetuximab, an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mAb, enhanced anticancer immunity, suggesting that Monalizumab could be used in combination with other oncology treatments. In patients with pretreated gynecologic cancers, Monalizumab was found to be well tolerated and showed short-term disease stabilization [63][162]. Preliminary data from microsatellite stable (MSS)-CRC patients who do not typically respond to anti-PD-1/PD-L1-based therapy showed the clinical efficacy and safety of the combination of Monalizumab and Durvalumab (an anti-PD-L1 mAb) [61][62][160,161]. On the other hand, the clinical trial (NCT04590963) in patients affected by head and neck cancer (HNSCC) and receiving Monalizumab and Cetuximab as a combination therapy did not meet objective response (https://yhoo.it/3oOARub, accessed on 24 January 2023). Currently, there are a number of ongoing clinical trials testing the efficacy of Monalizumab alone or in combination with other ICIs for the treatment of hematological and solid tumors (Table 2) that will progress the our knowledge.Table 2. Clinical trials with anti-NKG2A mAbs for the treatment of tumors.

| Clinical Trial | Phase | Status | Drug | Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04307329 | II | Active, not recruiting | Monalizumab + Trastuzumab | Breast cancer |

| NCT04590963 | III | Terminated | Monalizumab + Cetuximab | Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck |

| NCT05221840 | III | Recruiting | Monalizumab + Durvalumab | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| NCT02921685 | I | Unknown status | Monalizumab | Hematologic Malignancies |

| NCT02671435 | I/II | Completed | Monalizumab + Durvalumab | Advanced Solid Tumors |

| NCT02557516 | I/II | Terminated | Monalizumab + Ibrutinib | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| NCT05414032 | II | Not yet recruiting | Monalizumab + Cetuximab | Locoregionally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| NCT05061550 | II | Recruiting | Monalizumab + Durvalumab | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| NCT02643550 | I/II | Active, not recruiting | Monalizumab + Cetuximab + anti-PD-L1 | Head and Neck Neoplasms |

| NCT04333914 | II | Completed | Monalizumab | Advanced or Metastatic Hematological or Solid Tumor |

| NCT03822351 | II | Active, not recruiting | Monalizumab + Durvalumab | Unresectable Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| NCT03088059 | II | Recruiting | Monalizumab | Recurrrent or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck |

| NCT03794544 | II | Completed | Monalizumab + Durvalumab | Resectable Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| NCT03833440 | II | Recruiting | Monalizumab + Durvalumab | Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| NCT05162755 | I | Recruiting | S095029 ± Sym021 (anti-PD-1) | Advanced Solid Tumor Malignancies |

Monalizumab = anti-NKG2A, Trastuzumab = anti-HER2, Cetuximab = anti-EGFR, Durvalumab = anti-PD-L1, Ibrutinib = anti-CD20.

The activity of the above therapies is mainly attributed to the NKG2A+ NK and conventional CD8 αβ T cells [62][161], and nothing is known about γδ T cells. Our study shows that Vδ2 T cells infiltrating tumors such as GBM, NSCLC, HCC, and CRLM express high levels of NKG2A [9][24][17,29]. In some tumors (e.g., GBM, NSCLC), the percentage of NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells can exceed that of those circulating in the blood, although it is not clear whether this higher expression level is induced by the TME or whether it is due to the preferable infiltration of this subset to the tumor side. The degree of infiltration of highly cytotoxic NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells in some tumors can exert different impacts on patients’ OS in relation to the degree of expression of HLA-E. High frequencies of NKG2A+ Vδ2 TILs significantly correlate with improvement in patients’ OS in NSCLC and HCC tumors with similar levels of HLA-E compared to that present in normal tissue. On the other hand, in cases of GBM, there is a higher expression of HLA-E coupled with the lack of any clinical impact of NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells on patients’ OS. Although only correlative, these studies suggest that multivariate analyses matching the degree of HLA-E expression with the frequency of NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells might identify reliable targets to enhance Vδ2 T cell activity in several tumors.

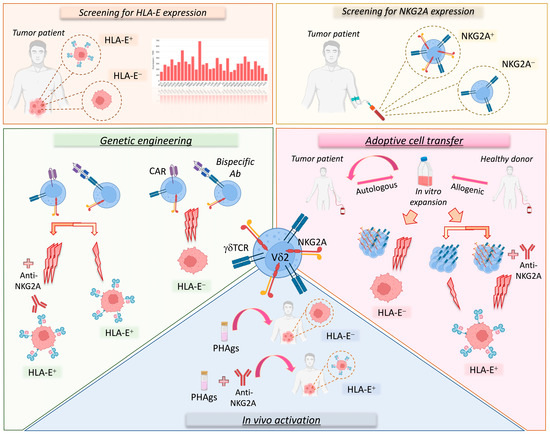

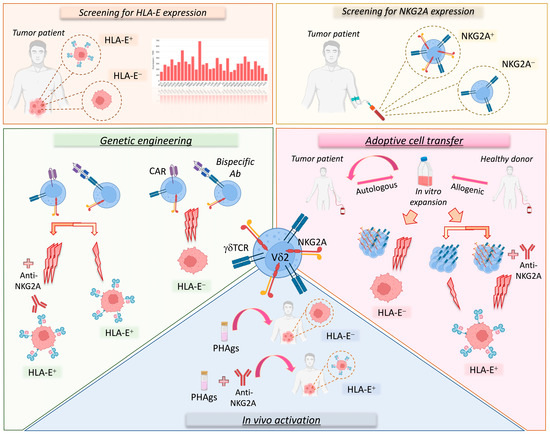

The implementation of Vδ2 T cells in different cancer therapeutic approaches, including their in vivo activation and expansion, adoptive cell transfer therapies, and genetic engineering, needs to optimize the efficacy of such treatments by selecting effector Vδ2 T cells that are endowed with the maximal anti-tumor potential (Figure 2). In this regard, rwesearchers need to consider that hyper-responsive NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells would provide a more powerful tool for eradicating malignant cells compared to adoptive cell transfer trials administering all γδ T cells. However, the clinical use of customized NKG2A+ or NKG2A− Vδ2 T cells should be matched with the histopathologic features of HLA-E expression to tailor those immunotherapeutic protocols to exert the most powerful immune responses against cancers.

Figure 2. Vδ2 T cell-based immunotherapeutic approaches considering the NKG2A-HLA-E immune checkpoint axis. Several therapeutic strategies targeting the NKG2A-HLA-E axis on Vδ2 T cells could be used to treat cancer patients. First of all, it is important to evaluate the expression level of HLA-E in the tumor as well as that of NKG2A on Vδ2 T cells (upper panels). In fact, tumors can be characterized by variable levels of HLA-E (orange square; HLA-E transcription levels in various cancer types; RNA-sequencing data for the expression of HLA-E gene are reported as transcripts per million (TPM) and generated by using the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis 2 (GEPIA2) web server). Moreover, both patients and healthy donors can show variable levels of NKG2A expression on Vδ2 T cells (yellow square). These parameters, along with the possibility of sorting NKGA+ or NKG2A− Vδ2 T cells, should be considered in immunotherapeutic strategies (lower panels). In particular, autologous or allogenic Vδ2 T cells can be expanded in vitro for adoptive cell transfer therapy. However, for tumors lacking HLA-E, it would be more suitable to use NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells, as they show higher cytotoxic (3 lightning bolts) potential, while for tumors expressing HLA-E, it would be more appropriate to use NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells in combination with anti-NKG2A mAbs or in alternative NKG2A− Vδ2 T cells could be used with lower cytotoxic (1 lightning bolt) capability (pink area). Analogously, in genetic engineering approaches (green area) based on CAR-γδ T cells or bispecific antibodies, the use of NKG2A+ Vδ2 T cells against HLA-E+ tumors would be optimal only in the presence of the anti-NKG2A mAb. However, additional investigations are needed to establish the expression of NKG2A on engineered Vδ2 T cells. Finally, for the in vivo activation of Vδ2 T cells (blue square), PhAgs could be used alone or in combination with anti-NKG2A mAbs for cancer patients with low or high levels of HLA-E, respectively.