Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Chika Oliver Ujah and Version 2 by Conner Chen.

High modulus of about 1 TPa, high thermal conductivity of over 3000 W/mK, very low coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), high electrical conductivity, self-lubricating characteristics and low density have made carbon nanotubes (CNTs) one of the best reinforcing materials of nano composites for advanced structural, industrial, high strength and wear-prone applications. This is so because it has the capacity of improving the mechanical, tribological, electrical, thermal and physical properties of nanocomposites.

- carbon nanotubes

- metal matrix composites

- polymer matrix composites

1. Introduction

Reciprocating movement of pistons inside engine cylinders, rotation of bearings and crankshafts, walking or running on tracks/roads, engaging and disengaging of brakes and clutches etc., are affected by a phenomenon called friction. Friction is the force which tries to resist motion of one body sliding over another. The classic law of friction was discovered back in 15th century by Leonardo da Vinci, even though it was not published then. It was Guillaume Amontons who rediscovered the laws in 1699. The laws were called Amonton’s laws of dry friction, which summarily stated that the force of friction (F) is directly proportional to the applied normal load (N) or that the coefficient of friction (μ) is directly proportional to the friction force and inversely proportional to the normal load.

Ever since then, research has been on-going on friction and tribology. Tribology is the science of friction, wear and lubrication. Light metals such as Al, Ti and Mg are applied in aerospace, automotive, agricultural and electrical industries because of their low density and their high strength per unit weight, besides other excellent properties. However, they are easily eroded and worn away by friction and wear which undermine their utility and efficiency in service. However, this anomaly can be augmented by introducing reinforcement which improves their tribological properties. Polymers, on the other hand, are more resistant to chemicals, are cost effective and require no post-production treatment like metals do, but they are weaker to friction and wear. So, to eliminate this challenge and improve durability and efficiency in service, they require some reinforcement with nanomaterials. Ceramic materials have high hardness, good thermal stability and high wear resistance, but they are very brittle. So, to improve their fracture toughness, they are reinforced with high-strength and high-modulus nanoparticles or nanomaterials. Lubrication can be referred to the practice of applying oil, grease or nanomaterial on a surface in order to minimize friction and wear. Among all the known nanoparticles/nanomaterials used in lubrication and improving wear resistance, strength and fracture toughness of materials, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) stand out [1][2][3][4][5][1,2,3,4,5].

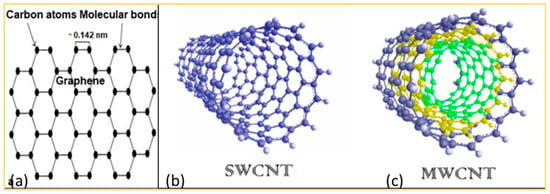

It was in 1991 that Iijima discovered, for the first time, a particular carbon with a structural configuration that looked like a tubule [6]. It consisted of some tens of graphite layers (walls) that were later identified as multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) or simply (CNTs) (Figure 1). Successive walls of the tubule are 0.34 nm apart, with diameter of 1 nm and massive aspect ratio. When graphite exists in 2 dimensional forms, it is called graphene (Figure 1a). Two years on, Iijima and his co-workers developed single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) (Figure 1b), which were formed when graphene was rolled into a seamless cylindrical tube [7]. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have been recognized as the stiffest material (bequeathed by its SP2 hybridization) which buckles elastically under massive bending or compressive stress. It possesses huge tensile strength of about 100 GPa and exceptional elastic modulus of 1.27 TPa, its thermal conductivity ranges from 3000–6000 W/mK, and its current density is about 1015 A/m2, with a conductance of 13 kᲲ−1 [6][7][8][9][10][6,7,8,9,10].

These exceptional characteristics of CNTs have provoked the interests of researchers on this material. The production techniques of CNTs are manifold, and they include: electric arc discharge, laser ablation, vaporization induced by a solar beam, and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [11][12][13][11,12,13]. Consequent upon the essential properties of CNTs, they have been applied as a reinforcement for metal, polymer, ceramic and carbon matrices. Based on its mechanical-cum-tribological characteristics in metal matrices, Park, Keum [14] reported three types of strengthening mechanisms in CNTs-reinforced composites, which included Orowan looping, thermal mismatch and load transfer kinetics. Orowan looping occurs during plastic deformation and is as a result of dislocation of atoms in the crystals. Thermal mismatch occurs when there is a wide difference between the coefficients of thermal expansion (CTE) of the matrix and reinforcement, just like in CNTs (2.1 × 10−6 K−1) and Al (2.36 × 10−5 K−1) [15]. In this case, thermal mismatch raises the dislocation density through strain hardening which culminates in the strengthening of the composite [16]. More so, CNTs can efficiently absorb the load incident on its base material through the dynamic load transfer mechanism, thereby raising the load bearing capacity of the composite system. Among the three mechanisms, it was reported that load transfer kinetics contributed more than 50% of the improvements [14].

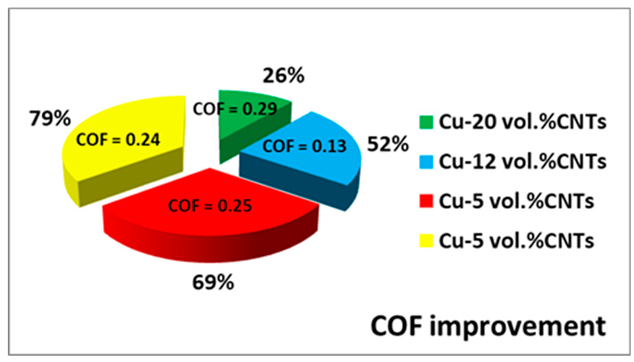

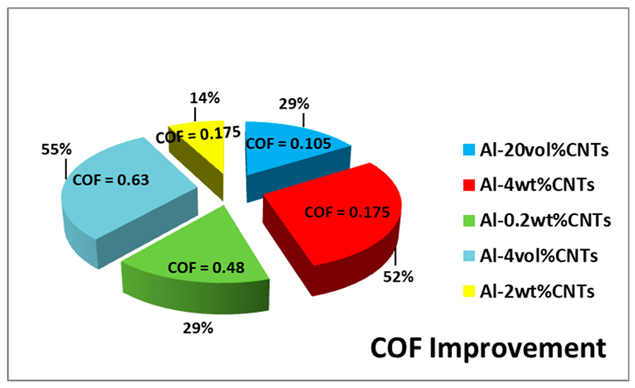

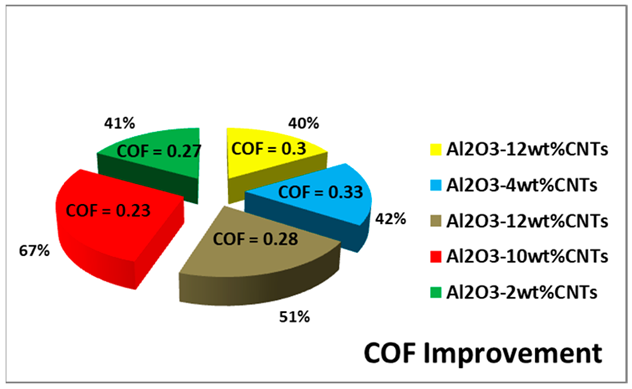

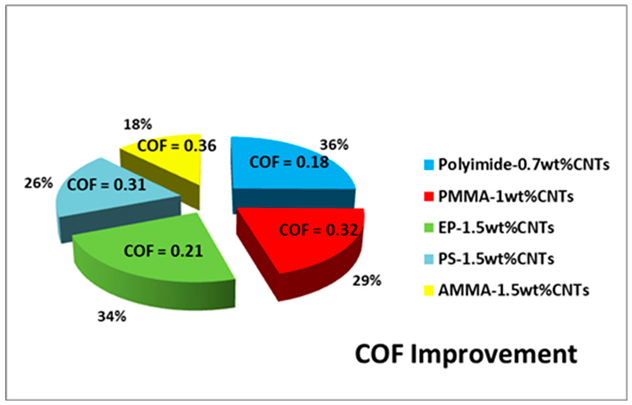

Nonetheless, there is a relationship between the mechanical strength and tribology of composite systems. It was in 1953 that Archard [17] propounded that the wear volume loss (V) of a material is inversely proportional to its hardness (H) and directly proportional to the sliding distance (S) and normal load (L). So, it can be inferred that materials with high strength (hardness) experience lower wear loss than those with low strength and vice versa. Meanwhile, the tribology of a composite system entails: the interaction of the surface with another surface when they are in a relative motion; the coefficient of friction (COF) of the system; the wear rate and wear loss of the system; and the lubrication properties of the system. Therefore, since it has been established that CNTs reinforcement improves the mechanical properties of composites, it is logical to assert that it improves the tribological properties of materials too. In addition, it has been shown that CNTs is a good solid lubricant [18]. Hence, incorporation of CNTs into a base material not only reduces the wear volume loss of the material but reduces the COF of the system which is promoted by the decrease in both the adhesive and deformation components of its coefficient [19]. Metal matrices reinforced with CNTs have exhibited excellent tribological properties, and this has caused the expansion of its engineering applications, industrial utility, automotive usage, aerospace, electrical and electronics applications [20][21][20,21]. In an experiment to investigate the tribological properties of Nickel-CNTs composite, it was discovered that 2 vol.% of CNTs gave the least COF of 0.22. When the volume fraction was increased to 5%, the COF increased, and other properties depreciated, because there was agglomeration of the reinforcement in the microstructure [22]. It was shown that the COF of Ni-2CNTs composite improved by 332% in comparison with monolithic Ni. The information herein is that optimizing the volume fraction of reinforcement is of paramount importance. This is because the high aspect ratio of CNTs provokes its agglomeration. So, once the optimal volume fraction is exceeded, homogenous dispersion becomes difficult. The COF improvements of different metals, ceramics and a number of polymers reinforced with CNTs are shown in Table 1. It can be observed in Table 1 that ceramics accommodated a higher volume fraction of CNTs than metals and polymers. A small volume fraction of CNTs (0.7 wt.%) improved the COF of polymers optimally. For metals, 4 wt.%–5 wt.% produced the optimal COF. This trend was equally observed by Watanabe et al. [23] who posited that ceramics are more hydrophilic than polymers due to their surface roughness. So, the degree of hydrophilicity of base materials controls the volume fraction of reinforcements that can be absorbed. Ceramics possess the highest hydrophilicity, followed by metals and then polymers.

Table 1.

Improvement of COF in Metals, Ceramics and Polymers Reinforced with CNTs.

| Plots of COF Improvements | Remark | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

|

5 vol.% of CNTs gave the optimal COF improvement. As the concentration increased, the COF depreciated in the Cu alloy. | [24][25][26][27][24,25,26,27] |

|

At a very low concentration of CNTs, the composite had low COF improvement; at too excessive a volume fraction, the improvement was still low. It was an optimal concentration (4 vol.%) that gave the highest improvement in Al alloys. | [28][29][30][31][28[,2932,30,31],32] |

|

The COF improvement in Al2O3 ceramic-CNTs composite absorbed higher volume fraction of CNTs than in metals and polymers. An optimum value of 10 wt.% gave the highest COF improvement of 67%. | [33][34][35][36][37][33,34,35,36,37] |

|

Polymer matrices can wet out only minute fraction of CNTs. Optimum concentration of CNTs that gave the highest COF improvement was 0.7 wt.%. (PMMA, polymethyl methacrylate; EP, epoxy; PS, polystyrene; AMMA, polyacrylonotrile). | [38][39][38[40],39,40] |

Furthermore, when CNTs reinforcement is incorporated into polymers, strong interfacial bonding between the nano-carbon chains and polymer matrices are achieved, and this increases the modulus of polymer composites and expands its industrial, engineering, pharmaceutical and agricultural applications [41]. There was a report that there exists strong interfacial adsorption energy in polymer-CNTs reactivity, which helps to bond the polymer chains on the surface of CNTs stoutly, thereby enhancing the strength of the CNTs-polymer composite [41]. Campo et al. [42] studied the effect of CNTs addition into epoxy matrix composite. The results showed that addition of 0.5 wt.% CNTs into epoxy matrix reduced the mass loss by 900%, decreased the wear rate by 1367%, and decreased the COF by 275%. However, the improvements were more pronounced when the CNTs were functionalized, as functionalization decreased the Van der Wall forces and hydrogen bonding in CNTs molecules. Wang et al. [43] studied the tribological behavior of plasma-sprayed carbon nanotubes-reinforced TiO2 coatings and discovered that the coating that had CNTs reinforcement exhibited about a 93.6% decrease in wear volume with a moderate decrease in the COF when compared with unreinforced TiO2. By and large, CNTs reinforcement has proven to be a good tribological nanomaterial for composite development. Reports on the tribological properties of CNTs-reinforced composites are scant in the literature [44]. Singh and Beloka [45] reported Al- and Mg-based composites reinforced with CNTs; Chan et al. [46] studied the effect of nanofillers on polymer composites; Goswami et al. [47] concentrated on mechanical and tribological properties of CNTs/graphene-reinforced alumina, while Choudhary et al. [48] dwelt more on the effect of processing route, processing parameters and CNTs length on the properties of CNTs-reinforced composites.

2. CNTs-Based Nano Materials

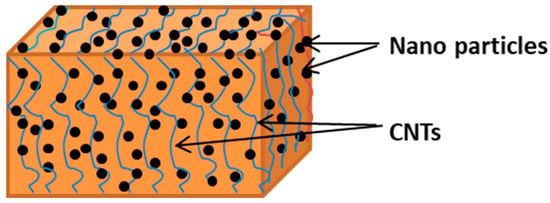

Two factors that are responsible for high strength of materials reinforced with CNTs are as follows: (a) the interlocking carbon-to-carbon covalent bonds of CNTs providing strong metallurgical bond to the composite and increasing its dislocation density. (b) The carbon nanotube existing as one large molecule which does not possess grain boundaries at all, let alone weak ones that separate crystal grains of high strength materials such as steel or tungsten [49]. Hence, there is no danger of grain boundary weakness or failure. Figure 2 gives a schematic idealization of a CNTs-reinforced composite system. As shown in Figure 2, each particle of the matrix is actively held together or bonded by the CNTs molecules making it difficult to be broken without application of enormous force. So, the SP2 covalent bond as well as single unit molecule of CNTs account for the exceptional strength of CNTs-based composite materials.

Figure 2.

Image of CNTs-Reinforced Nanocomposite.

Researchers have studied the traditional fibers such as carbon-, glass- and Kevlar- based composites via computational and empirical techniques. Energy densities, ballistic impact capacity, wear and penetration resistances of these traditional fiber-based composites were investigated. Challenging issues such as delamination, compressive failure in the fiber/matrix interface, matrix cracking, and tensile failure of yarns were all identified as the principal failure mechanisms after characterization [50][51][52][50,51,52]. However, it was observed that failures in these conventional composites occur within the range of a micrometer. This implies that reinforcement based on nanomaterials such as CNTs can withstand such failures. Hence, they can improve the mechanical/tribological properties of nanocomposites under steady and repeated loading and prevent such failures that occur at the micrometer scale. So, conventional composites are now being replaced by nanocomposites and hybrid composites in most advanced applications, due to their excellent mechanical, tribological, and thermal properties [53]. Improvement in strength and energy absorption of CNTs-reinforced polymer/glass composites has been reported [54]. Also reported is the improvement in tribological, thermal, corrosion and mechanical properties of CNTs-reinforced metal/ceramics matrix composites [55][56][57][55,56,57]. It is because of the excellent mechanical and tribological properties, thermal and electrical conductivities that carbon-based nanofillers such as CNTs and graphene are employed in the development of nanocomposites [58][59][58,59]. It was reported that CNTs-reinforced polymers nanocomposites are presently being used in the place of steel in the development of bullet-proof shields, jackets, wear resistant surfaces, shock and impact absorbers, and ballistic impact-resistant materials [60][61][60,61], and they are much cheaper, less dense, more corrosion resistant and more robust than the conventional steel-based military armors and shields. CNTs-reinforced metal matrix composites, on the other hand, are used in the development of aerospace components, automotive piston and sleeves, nozzles, turbine blades, transmission conductors, electronic sensors and transmitters [20][62][63][64][20,62,63,64], as they outperform monolithic Al, Ti, Mg or steel alloys. Fracture toughness is one of the principal properties imparted on ceramic matrices by CNTs. Hence, CNTs-reinforced ceramic composites are used in the development of high temperature nozzles and turbines, cutting and drilling tools, blades of lathes, pulverizers etc. [65][66][65,66], and they are cheaper, less dense and more robust than tungsten, diamond and steel alloys that were the traditional materials for these equipment.

The production techniques of CNTs-reinforced nanocomposites are manifold. They can be grouped based on the similarity of processes involved. These groups include (i) powder metallurgy, (ii) electrochemical techniques, (iii) casting method, (iv) thermal spraying and (v) other novel techniques. Table 2 shows sketches of the production techniques used in the development of nanocomposites.

Table 2.

Production Techniques of Nanocomposites.

| Production Technique Sketches | Description | Remarks | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

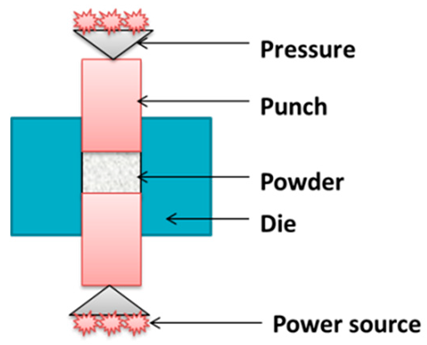

(a) Powder metallurgy |

Powder metallurgy: This comprises spark plasma sintering, vacuum sintering, microwave sintering, hot pressing and conventional sintering. Prior to consolidation, matrix and reinforcement are blended via ball milling, tubular mixing and molecular mixing. Then, the application of heat and pressure is used to consolidate the composite. | In SPS and other forms of advanced sintering, heat and pressure are applied concurrently, while in conventional sintering, heat is applied after green compaction. There is zero waste of materials. | [67 |

Wear and Friction Properties of Composites Developed with CNTs Reinforcement

Wear and friction characteristics of composites developed with CNTs reinforcement are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Wear and Friction Characteristics of CNTs-Reinforced Composites.

| CNTs/Composites | Tribology Properties | Remarks | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ] | |||||||

| AlSi-10Mg-CNTs | Wear grove of composite = 150 μm2 Wear grove metal matrix = 224 μm2 Wear rate of composite is 33% lower |

The improvement in wear rate is attributed to the fact that CNTs increased the hardness of the MMCs and improved the microstructure. Selective laser melting (SLM) was the technique employed. This composite is useful in automotive brake pad and lining, pistons and engine sleeves. | [70] | ||||

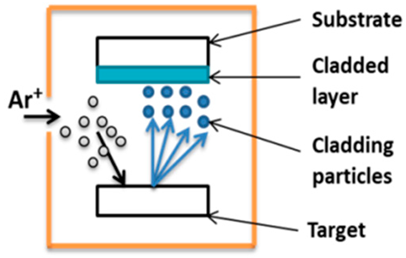

(b) Additive process |

Additive manufacturing: This comprises laser cladding, sputtering, nanoscale dispersion, sandwich processing, plasma spraying and vapor deposition. | ||||||

| WC-20Co-6CNTs | Wear rate = 0.000307 ± 0.1 mm | This technique reduces material wastes to the lowest level. | 3/N.m COF = 0.08 ± 0.012[68] |

||||

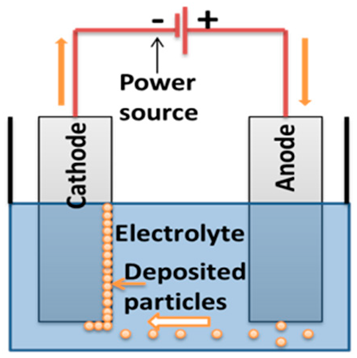

| The introduction of CNTs on WC-20Co improved the wear loss, wear rate and coefficient of friction greatly through improving the mechanical strength. The processing technique was high-velocity oxy-fuel (HVOF) spraying. This ceramic composite is useful in cutting tools and grinding wheels. | [ | 57 | ] |  (c) Electrochemical method |

Electrochemical technique: This comprises electro deposition via amperometry, potentiometry, conductometry, voltammetry or the galvanic cell technique. This involves the passing of electric current to initiate dissolution and deposition of materials. | The major advantages of this technique are its simplicity, low cost and speed. | [69] |

| Al2O3-3%TiO2-3% CNT, | Wear resistance = 5800 Nm/mm3 Mass loss = 0.0035 g Average mass loss of unreinforced ceramics was 3.85 mg, while average mass loss of CNTs/ceramics was 3.45 mg (11.6% improvement). |

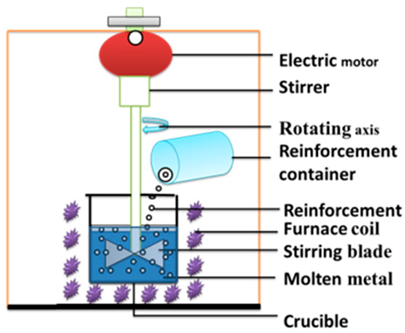

Uniform CNTs dispersion and good adhesion of coatings with the substrate invoked the enhancement of the wear properties. The method was Plasma Spraying of Al2O3-3TiO2-CNTs on AISI 1020 steel substrate. This ceramic composite is replacing steel pipes in oil and gas industrial pipes. | [71] |  (d) Casting method |

Casting method: This comprises stir casting, ultrasonic cavitation, squeeze casting, liquid casting etc. Casting involves melting of base material, addition of reinforcing phase, stirring and solidification. | ||

| 316 L Stainless steel-8CNT | Wear rate = 1.1 × 10−7 mm3/Nm (218% improvement) COF = 0.25 (60% improvement) The COF of unreinforced 316 L was 0.4, and the wear rate was 3.5 × 10−7 mm3/Nm. | Virtually every component can be casted, using metal composites, ceramics or polymer composites. It is cheap and uses simple tooling. | [67] | ||||

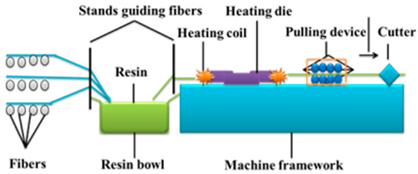

| The tribology improvement was made possible because the larger surface area of CNTs provided large surface roughing, thus having a better lubrication effect. Vacuum hot-press sintering was the technique applied. This steel composite is replacing conventional stainless steel in advanced applications. |  (e) Pultrusion/Extrusion |

Low melting-point metals and polymer composite fabrication that comprises pultrusion and extrusion. This involves melting and pushing or pulling the melt through an orifice to assume specific shape. | This is used in the production of long components such as electric transmission conductors. It is very fast and economical. | [67] |

| [ | |||

| 55 | |||

| ] | |||

| AZ61Mg-0.5%CNTs | Volume loss = 0.81 mm3 (48% improvement) Mass loss = 0.008 g (38% improvement) COF = 0.3 (17% improvement) There was very low COF (0.22) at 1 wt%CNTs. The unrefined AZ61 had volume loss of 1.2 mm3, mass loss of 0.011 and COF of 0.35. |

The strengthening and bonding characteristics of CNTs led to a reduction in mass loss. Additionally, the CNTs provided lubrication effect which led to enhancement of the tribology. Stir casting with annealing was the method used. This MMC is useful in electrical and electronics packaging. | [72] |

| Al3Ti-Cu-SiC-CNTs | Average COF = 0.46 Average COF of substrate = 0.57 This gives an improvement of 24% |

The COF was enhanced by the dispersion strengthening and fine grain strengthening of CNTs. The production technique was laser cladding. This is an advanced hybrid composite which can compete favorably with high entropy alloy in aerospace applications. | [73] |

| Al2O3-3TiO2-6CNTs | Wear depth = 4 ± 0.8 μm Wear rate = 0.0003 ± 0.1 mm3/Nm COF = 0.11 ± 0.009 |

The improvement was attributed to bridging of CNTs in between the splats of the ceramics matrix. The technique used was Plasma Spraying of the composite on AISI 1020 mild steel. This is replacing steel alloy in bridges, rails and other structural applications. | [74] |

| Polyimide-0.1CNTs | Wear rate = 0.0002 mm3/Nm COF = 0.26 |

The functionalization of CNTs contributed to the improvement of the wear resistance. This polymer composite is used as high temperature structural glues and laminating resin. It is used in wood work, structural and car body parts applications. | [38] |

| Polyimide-0.7CNTs | Wear rate = 0.00065 mm3/Nm COF = 0.18 |

There was strong interfacial bonding between PI matrix and MWCNTs-COOH nanofillers, which enhanced the transfer of load effectively from the matrix to the functionalized CNTs. So, this improved its hardness, which in turn reduced the wear rate and COF. It is now prominent in automotive industries. | [38] |

| Phosphate ceramic-0.75CNTs | Wear rate = 0.008 mm3/Nm COF = 0.39 |

It was observed that at temperatures below 500 °C, the lubrication effect of CNTs was intact. However, when this temperature was exceeded, the tribology properties diminished. | [75] |

| Al2O3-2CNTs | Wear rate = 0.00000269 mm2/kg Wear rate of pristine Al2O3 = 0.00000294 mm2/kg |

The improvement in wear rate was attributed to the uniform dispersion and the reinforcement efficiency of CNTs. The composite was produced with cold spraying. This is a high-temperature structural ceramic composite that is replacing BN, WC etc. | [76] |

| Al-CNTs | Specific wear rate of micro-sized channel reinforcement filling (MCRF) = 0.018 mm3/Nm Wear rate of pure Al = 0.022 mm3/Nm (20% improvement) |

The improvement in wear rate was attributed to the uniform dispersion of CNTs in MCRF-fabricated composite, which formed a solid lubricant layer. Friction stir processing was the method applied. This MMC is useful in electrical, electronic and structural applications which can replace conventional steel conductors. | [77] |

| Al-Si-0.75CNTs | Wear rate = 0.00095 mm3/m Wear rate Al-Si = 0.0018 mm3/m (89% improvement) |

The improvement was attributed to the formation of a carbon layer which acted as a solid lubricant at a higher speed. Powder metallurgy was employed in the fabrication. | [78] |

| Al-4CNTs | COF = 0.18 (52% improvement) Wear rate = 0.34 μm3/s (23% improvement) Wear volume = 20 μm3 (23% improvement) |

The improvement was attributed to strong densification and refined microstructure influenced by spark plasma sintering technique. Useful for high temperature transmission conductor. | [18] |

| Al-8CNTs-8Nb | COF = 0.10 (79% improvement) Wear rate = 0.49 μm3/s (23% improvement) |

The improvement was attributed to the solid lubrication property of CNTs and formation of Nb2O5 that acted as a solid lubricant too. This can conveniently replace steel-reinforced aluminum conductors. | [79] |

| Epoxy-10Carbon fibre-0.3CNTs | COF = 0.3 (97% improvement) Wear rate = 4 × 10−6 mm3/Nm (425% improvement) |

The improvement in the tribological properties was attributed to the lubricating effect as well as strengthening action of C-C bond between CNTs and short carbon fibre. This polymer composite is useful in high-temperature applications. | [80] |