Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Lenard Farczadi and Version 2 by Camila Xu.

Glyphosate, also known under its IUPAC name N-(phosphonomethyl) glycine, while discovered by a Swiss chemist, Dr. Henri Martin, was initially developed as a chemical chelating agent, a chemical intermediate for the synthesis of other molecules, and as a possible bioactive compound.

- glyphosate

- exposure

- biomonitoring

- bioanalytical methods

1. Introduction and Background—Glyphosate Use and Exposure

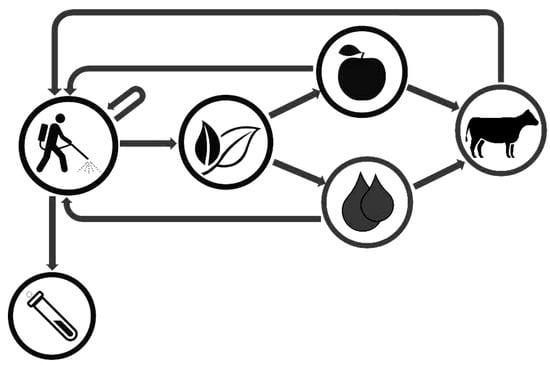

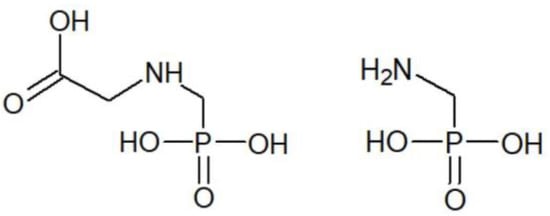

Glyphosate, also known under its IUPAC name N-(phosphonomethyl) glycine, while discovered by a Swiss chemist, Dr. Henri Martin [1], was initially developed as a chemical chelating agent, a chemical intermediate for the synthesis of other molecules, and as a possible bioactive compound [2]. Independently, sometime later, due to the potential of chelating metals, a number of derivatives of aminomethylphosphonic acid (Figure 1) including glyphosate (Figure 1) were studied as potential water-softening agents [1]. During the research, however, the herbicidal activity of some of these compounds was discovered, and after some study, glyphosate was discovered to be a promising candidate for such use [1]. Not long after this discovery, the first commercial formulation of glyphosate to be used as a broad-spectrum weedkiller was created [1].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of glyphosate (

left

) and aminomethylphosphonic acid (

right

).

Glyphosate base plant protection products are effective herbicides by inhibiting an important plant enzyme, 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase, which is present in plants and fungi, but not in animals and humans [3]. This enzyme is part of the biological mechanism during which plants synthesize aromatic amino acids. These amino acids are essential in many ways for the survival and growth of plants; thus, glyphosate inhibits the plant from functioning normally and slowly leads to the deterioration of the plant, both overground and underground. Loss of herbicidal activity occurs through the hydrolysis of glyphosate into its main metabolite aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) [3].

To improve the efficacy of glyphosate, modified crops have been developed, which are resistant to glyphosate by genetically engineering plants to express genes from a type of bacteria, after discovering that it contained a form of the enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase, which is not inhibited by glyphosate [4]. This made the use of glyphosate the first choice for crop farming as it facilitated the destruction of unwanted weeds without affecting crops.

Glyphosate is a polar, readily water-soluble compound; it tends to partition in water versus air and easily absorbs into the soil particles. During application, small quantities of aerial drifts, splash, or drip can cause harm to non-target surrounding plants. Glyphosate is highly chemically stable in water in a wide pH-range and is not photosensitive to degradation from sunlight. The main path of the decomposition of glyphosate in water and soil particles is through microbial degradation and is dependent on the type and number of microorganisms [3].

Due to its wide use in recent years, concerns have grown with regard to its toxicity and the health risks involved with exposure to glyphosate and glyphosate-based herbicides [5]. While some regulatory agencies consider that it does not pose a risk to public health and that it is unlikely to be carcinogenic to humans [6][7][6,7], others have concluded that it is a “probably carcinogenic” substance to humans [8]. Most regulatory authorities, however, have concluded that it is necessary to limit the human intake of glyphosate. Although it is a controversial topic and it is still debated whether it has a role as a tumor cell initiator or promoter, and studies are still ongoing, there are results that have shown the cytotoxicity, involvement in genetic damage, and even some tumor promoting activity of glyphosate [9][10][9,10].

In 2017, the license for glyphosate use in the European Union was renewed for five more years until December 2022, after the previous 15-year license had expired, causing a controversial and highly divisive debate [11]. As glyphosate residues have been detected in food, groundwater, and even drinking water [12][13][12,13], most regulatory agencies around the world, even those that have classified it as posing no risk to public health, have imposed limits on the exposure and intake for humans, currently at 1.75 mg/kg bw/day in the USA and 0.5 mg/kg bw/day in the EU (increased in 2015 from 0.3 mg/kg bw/day) [13][14][15][13,14,15]. Some independent scientists, however, consider these limits to be too high, suggesting an acceptable daily intake of 0.1 mg/kg bw/day or less [16].

Biomonitoring in glyphosate exposure is not only a challenge, but is should also be a must for both the occupational and non-occupational exposed population, considering the high amount of usage worldwide. For example, in the European Union, the total glyphosate sales in 2017 reached 44,250 tons, accounting for a proportion of 34% of all herbicides [17]. It is estimated that around 11–13% of agricultural workers are exposed to glyphosate [18], which makes the need for glyphosate biomonitoring of even greater need.

In a series of 13 acute glyphosate poisonings, Zouaoui et al. [19] described the associated symptoms such as respiratory alteration, oral and pharynges ulceration, hepatic and renal toxicity, cardiac arrest, laboratory parameters disturbed, and many other affected organs. The authors indicated a mean value of 61 mg/L glyphosate in blood in mild–moderate intoxication, a mean concentration about fourteen times greater in severe intoxication, and sixty-eight times higher in mortal cases.

During a study performed on farmers of different crops in Thailand, Wongta et al. found that the occupational exposure of the farm worker groups led to significant, quantifiable levels of glyphosate in the urine of a large percentage of them compared to a control group that showed no detectable urinary glyphosate [20]. Urine concentrations were between an average of 2.01 ng/mL and 3.11 ng/mL for the different types of farmer groups and was thought to be worsened by the lack of protective equipment for the farm workers. Similar previous studies performed by researchers in this group have also shown that the occupational exposure of farm workers from other regions of Thailand have similar quantifiable glyphosate levels in urine [20].

A study by Melissa Perry et al. on historical urine samples collected decades prior from American farmers exposed to glyphosate also showed that compared to non-users who had no detectable traces of glyphosate in their urine, the farmers actively using glyphosate on their crops, for the most part, had quantifiable levels of urinary glyphosate with an average of 4.04 μg/kg urine, and as high as 12.0 μg/kg urine [21].