The load integrals (impulse) over the central metatarsal region significantly increased, indicating that surgeries increased the risk of transfer metatarsalgia. There is no solid evidence that hallux valgus (HV) surgeries could improve forefoot functions from a biomechanical point perspective. Surgeries might reduce the plantar load over the hallux and adversely affect push-off function.

- bunion

- hallux abducto valgus

- metatarsus primus varus

- pedobarography

1. Introduction

2. Forefoot Function after Hallux Valgus Surgery

A meta-analysis showed that there was a reduction in hallux and medial forefoot load/impulse that implicated the failure of surgeries to restore forefoot functions [25][Reference.: DOI: 10.3390/jcm12041384] . Besides, the pain-causing load at the central forefoot was not lessened. The pathomechanics that manifested transfer metatarsalgia was thus not resolved.

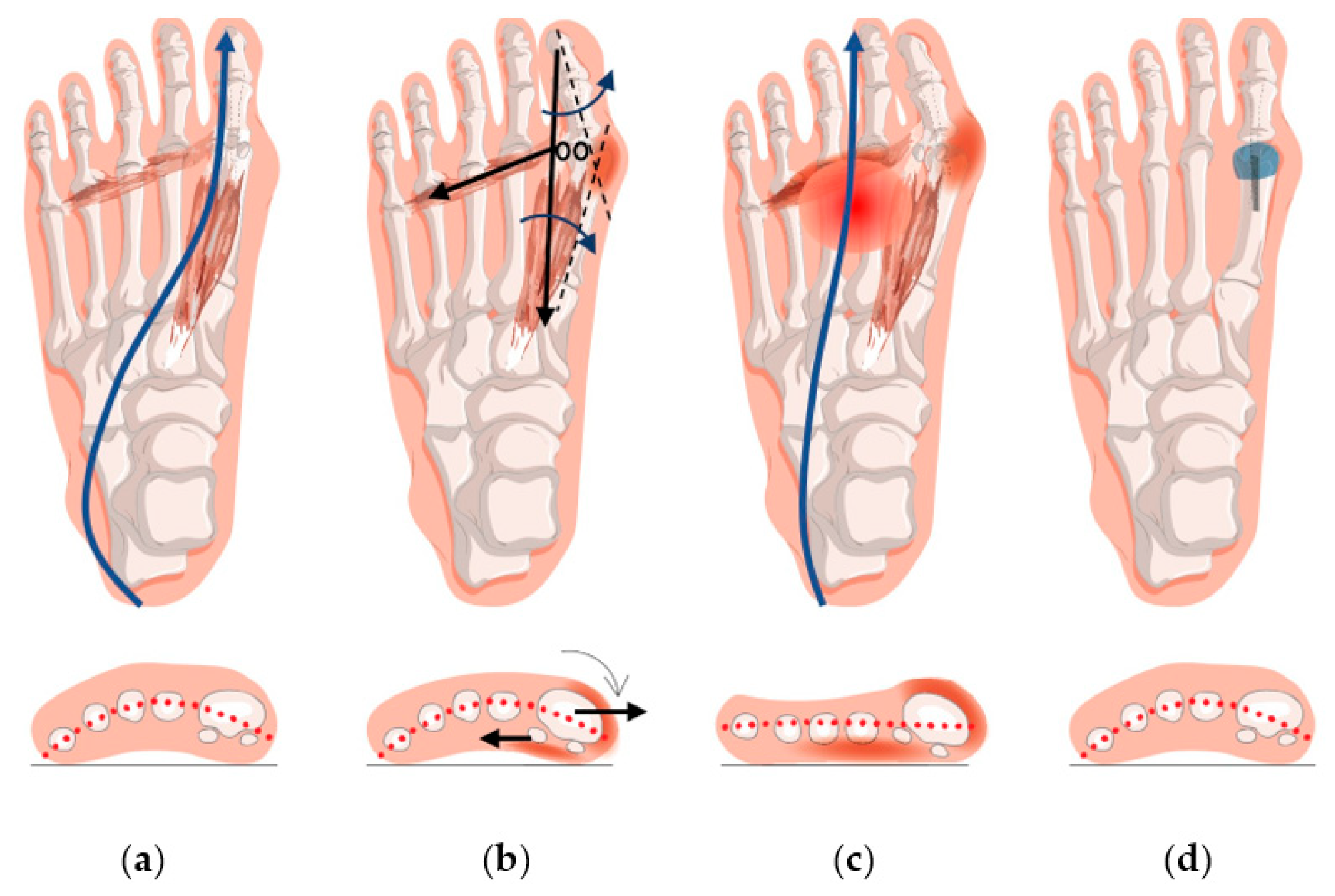

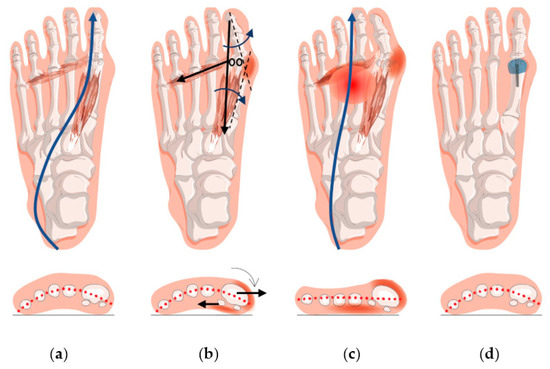

Although substantial heterogeneity was observed in the meta-analysis [25][Reference.: DOI: 10.3390/jcm12041384], most of the individual studies did not favor surgeries, and some did admit that surgical interventions failed to restore normative plantar functions or produced no significant biomechanical improvement [26][27][28][29][30][31][25,33,35,38,39,54]. One possible explanation for the finding is that some of the included studies were old, and the surgical technique or plantar pressure instrument might have been flawed at that time. Nevertheless, subgroup analyses by year of publication indicated that this lack of effectiveness was unlikely due to whether the surgical methods were old or relatively new. Another reason for the failure could be premature ambulation with pain, stiffness, and weakened intrinsic muscles [28][31][35,54]. Indeed, a significantly worse load distribution on the hallux and central metatarsal region was observed in the studies with a shorter follow-up period (<12 months). A third reason could be related to the elevation of first metatarsal head in the surgical procedure in some studies, which might produce negative impact on the plantar pressure. Elevated or a more dorsal position of the first metatarsal head might reduce the load-carrying capacity of the first ray, which was recognized as the cause of metatarsalgia and poor surgical outcomes [32][30]. Some osteotomy techniques, such as Crescentic [26][25], closing wedge [33][57], and Weil [34][58] are vulnerable to the elevation of the first metatarsal. Nevertheless, the analysis did not support this fact as the source of heterogeneity. A fourth reason is that the surgeries may not correct or ameliorate hypermobility or instability of the forefoot, which is the etiology of HV [35][59]. Besides, mainstream surgical techniques may fail to repair the stabilizing soft tissue structures and the underlying soft tissue deficiency or imbalance, which adversely affect the load-carrying capacity [36][60].

The “negative” biomechanical effects of HV surgeries demonstrated seem to contradict the positive clinical improvement after surgeries. It hypothesizes that immediate pain relief and restoration of daily functions might not necessarily complement the resumption of normal foot kinematics and walking capability, which is a secondary measure to contemplate potential deformity recurrence, complications, compensatory foot problems, and falling risks. Surgeries treat the bone misalignment of HV but might not be treating the root cause of the problem.

In fact, HV surgeries could remedy bunion (swollen joint) problems, shoe-fitting issues, and facilitate immediate pain relief. Moreover, the restoration of bone alignment ameliorates push-off functions by correcting the position of the sesamoid bones and muscle directions. Radiographic assessment and patient-reported outcomes are undoubtedly the primary outcomes, reflecting deformity correction and immediate pain relief. Yet, these evaluation measures are insufficient, and perceived pain relief may not necessarily be associated with restoration of biomechanical functions [37][47]. Plantar load measurements examine whether the corrected foot could resume normal foot kinematics and walking capability and could serve as a secondary measure to contemplate potential deformity recurrence, complications, compensatory foot problems, and falling risks. Thus, it would be desirable to have surgeries that are effective in improving plantar load distribution. Some surgeons endeavor to develop alternative surgical methods, including metatarsal suturing techniques (e.g., mini-tightrope) that could reinforce the site stability and minimize the risk of traumatizing osseous procedures [38][61]. However, the effectiveness of these methods warrants further investigation.

Postoperative rehabilitation, such as orthosis and muscle training, plays an important role in load redistribution and regaining foot functions. Postoperative muscle retraining could strengthen hallux functions, restore joint mobility and thus physiological gait patterns [39][40][49,62]. Schuh et al. [39][49] commented that the strengthening of peroneus longus muscle can facilitate a better midfoot pronation control and therefore direct load to the first ray correctly. Foot orthosis with arch support could also help control pronation [41][63], while a metatarsal pad could relieve pain and maintain the integrity of the transverse arch, in cases of first ray insufficiency [42][43][44][64,65,66]. Besides, despite that an increase (or a restoration) of first ray load indicated the restoration of biomechanical functions, it should be noted that unloading the first ray by immobilization or partial weight bearing in the early postoperative stage is essential to facilitate pain management and mitigate risks of non-union [45][46][47][44,50,67].

Besides the variations of surgical techniques, the intrinsic features of HV, such as spring ligament insufficiency [48][70], first ray hypermobility [49][71], hypermobility due to malpractice in amateur ballet dancers [50][72], generalized ligament laxity [51][73], medial column instability, and posterior tibial tendon dysfunction [52][74], may have contributed to clinical heterogeneity as well. Moreover, HV was often compounded with other foot problems that were infeasible to isolate [35][53][59,75], such as flatfoot [54][76], plantar fasciitis [55][77], transfer metatarsalgia [18], and claw toes [56][78]. There is limited research on the impact of plantar pressure under such circumstances. Those additional foot problems may contribute to variations in plantar loading pattern or postoperative compensatory gait [18][57][18,79]. For example, individuals with flat feet might not have sufficient load under the medial forefoot during push-off [58][80], while those with valgus hindfoot deformities might have higher medial forefoot pressures [59][81].