You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 1 by Stephen H. Safe.

Coffee is one of the most widely consumed beverages worldwide, and epidemiology studies associate higher coffee consumption with decreased rates of mortality and decreased rates of neurological and metabolic diseases, including Parkinson’s disease and type 2 diabetes. In addition, there is also evidence that higher coffee consumption is associated with lower rates of colon and rectal cancer, as well as breast, endometrial, and other cancers.

- coffee

- AH receptor

- Nrf2

1. Introduction

Coffee is among the most widely consumed beverages in the world, and it is estimated that over two billion cups of coffee are consumed daily [1,2][1][2]. Coffee intake is highly variable with respect to different countries, ages, and sex, and there appears to be a continuing increase in consumption which parallels, in part, the increasing number of specialty coffee shops in many countries. Coffee intake is often associated with the stimulant caffeine, which is a major component of coffee, and the average caffeine intake in the United States is 135 milligrams per day, which is equivalent to about 1.5 cups per day. Many individuals consume up to 6 cups of coffee per day and much higher amounts of caffeine. Although roasted coffee beans and brewed coffee contain high levels of caffeine, there are several hundred individual phytochemical-derived compounds in coffee, and these include chlorogenic acid/lignans, alkaloids, polyphenolics, terpenoids, melanoidins, vitamins, and metals [3].

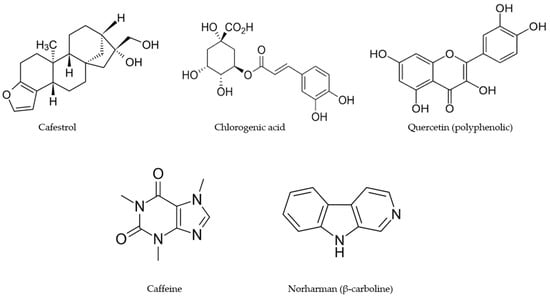

Figure 1 illustrates some examples of the compounds identified in coffee, and these include the flavonoid quercetin, chlorogenic acid, caffeine, the alkaloid norharman (β-carboline), and the terpenoid cafestrol. The health impacts of coffee consumption have been extensively investigated and are associated with lower all-cause mortality, diabetes mellitus, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, cardiovascular disease, and many types of cancer [2,3,4,5,6][2][3][4][5][6]. The effects of coffee on mortality and other diseases have been extensively investigated in many countries and in groups of individuals that are both “normal” or have specific health problems. The results of recent and past studies clearly show the overall health benefits of higher coffee consumption compared to lower consumption; however, there are also many studies that do not correlate and, in some cases, report conflicting results. The reasons for these differences in some cases may be the failure to examine the effects of sex dependency; however, many other potential unknown confounders may be involved and these need to be further investigated.

Figure 1.

Structures of individual compounds in roasted coffee after extraction with hot water.

2. Coffee and Health Benefits: Non-Cancer

2.1. Mortality

A number of recent studies (2020–present) have demonstrated that the higher consumption of coffee is associated with decreased mortality in both men and women. For example, in the UK Biobank study [2], the coffee intake of 395,539 individuals was collected between 2006–2010, and their overall disease-specific mortality was followed through 2020 (a median follow-up of 11.8 years). High levels of coffee intake (≥4 cups/day) were inversely associated with mortality from 30 of 31 diseases, with HRs ranging from 0.61–0.94, and these inverse associations were more predominant in women vs. men [2]. Interestingly the association between a high vs. low consumption of coffee in this population and mortality from various diseases was dependent on multiple variables, which include the sex of the individual, specific diseases, regular vs. decaffeinated coffee, and consumption levels. Examples of male vs. female differences with respect to a high vs. low consumption of coffee were associated with female/male HR values of 0.73/1.0 (digestive disorders), diabetes mellitus (0.74/0.92), and gout (0.71/0.59). In this study, there were “2 distinct clusters of medical conditions affecting mainly the cardiometabolic and gastrointestinal systems” [2]. In contrast, other studies did not observe inverse associations between coffee consumption and decreased mortality from neurogenerative diseases. Other studies in Korea [4], the United States [7,8,9[7][8][9][10],10], an Asia cohort [11], and an adult Mediterranean population [12] also reported that the higher consumption of coffee is associated with decreased mortality. Thus, the overall effect of coffee on mortality is comparable to previous and ongoing studies on other groups, including Seventh Day Adventists and the consumption of a Mediterranean diet, where high intakes of vegetables are also associated with decreased mortality [13,14][13][14].

2.2. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs)

In the Biobank study noted above [2], there was a strong association between decreased mortality from cardiometabolic diseases and the higher consumption of coffee [6], and this was also observed in a recent study on the Biobank population [15]. In contrast, a meta-analysis of 32 prospective cohorts reported that various studies showed that higher coffee consumption was associated with increased, decreased, or no effect on CVD [16]. In the UK Biobank studies, the higher consumption of coffee was associated with higher total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol levels, and this was highest in the expresso coffee drinkers [17]. A meta-analysis of studies showed that higher coffee consumption was associated with “an increased risk of CHD in men and a potentially decreased risk in women” [16], and an increased risk was also observed in another analysis of the UK Biobank population [18]. Another recent report indicated that, among individuals with grade 2–3 hypertension, the HR mortality values were 0.98 (<1 cup/day), 0.74 (1 cup/day), and 2.05 (≥2 cups/day) compared to noncoffee drinkers [19]. In contrast, it was also reported that the medium–high consumption of coffee (3–5 cups/day) had a beneficial or neutral impact on hypertension and blood pressure [20]. Thus, the relationship between the higher consumption of coffee and mortality from cardiovascular diseases is somewhat variable between studies, and the factors that modulate the impact of the effects of coffee on this disease need to be determined.

2.3. Neurological Diseases

The linkage between higher coffee consumption and decreased mortality for neurologic diseases such as dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease have been extensively investigated, and the results has been variable. It was recently confirmed that high coffee consumption is associated with decreased risks of neurological disorders, including dementia, stroke, and Parkinson’s disease [16,17,19,21,22,23][16][17][19][21][22][23]. These results were also observed in the UK Biobank prospective study [24]. As noted above, another report using the UK Biobank did not observe any correlation between coffee consumption and decreased mortality from neurodegenerative diseases [2]. A negative finding was the association between the early age of onset of Huntington’s disease with increased coffee consumption, and this outlier might be due to the strong genetic origins of this debilitating autosomal dominant disease [25]. However, there is evidence for the improvement of specific neurologic conditions with coffee consumption. For example, the moderate consumption of mocha coffee in an elderly population was associated with higher cognitive and mood status [26]; coffee consumption enhanced the age at onset of Parkinson’s disease in Ashkenazi Jewish patients [27]; the results of a meta-analysis showed that coffee consumption reduced the risk of overall stroke, hemorrhagic, and ischemic stroke [28]. Thus coffee–neurological disease interactions are variable in terms of mortality; however, there is evidence of protection from nonlethal neurological diseases that also needs to be considered and more fully investigated.

2.4. Metabolic Diseases including Diabetes

The higher consumption of coffee is also associated with a decreased risk of metabolic diseases and type 2 diabetes [29,30,31,32,33,34][29][30][31][32][33][34]. An analysis of plasma biomarkers in nondrinkers vs. individuals consuming ≥4 cups/day showed that in the latter group, the changes in biomarkers were consistent with favorable outcomes [31]. For example, higher concentrations of sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) (5.0%), total testosterone (7.3 and 5.3% in women and men, respectively), and total (9.3%) and high molecular weight (17.2%) adiponectin were increased in the coffee drinkers. In contrast, the group consuming high amounts of coffee exhibited lower levels of inflammatory markers, such as interleukin-6 (−8.1%), soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor (−5.8%), and C-reactive protein (−16.6%) [31]. These results were obtained from two large prospective studies: the Nurses Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study in the United States [31]. There is also evidence that coffee consumption interacts with other factors that modify the association between coffee and metabolic diseases. For example, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, coffee intake was associated with lower metabolic syndrome scores [33]; increased caffeinated and noncaffeinated coffee intake protected against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) severity in individuals with type 2 diabetes [35], and similar results were observed in a normal population [36]. The protective effects of coffee on metabolic disorders were also observed in individuals with a history of gestational diabetes [37], diabetic retinopathy [38], and hepatitis B viral infection [39]. These results are complemented by several recent studies showing that high coffee consumption is also associated with protection from inflammatory bowel disease and gut recovery in gynecological patients from surgery [40,41,42][40][41][42].

2.5. Sex-Dependent Effects of Coffee Consumption

The sex-dependent development of some diseases has been described and is thought to be due to multiple factors; there is some evidence for differences with respect to the effects of coffee on males and females [43]. The higher consumption of coffee decreased the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an adult Taiwanese population, and the protective effects were more pronounced in women [44]. In a UK Biobank study [2], the overall effects of high coffee consumption among subgroups of diseases were higher for women than men and this was particularly evident for functional digestive disorders and diabetes mellitus, whereas men were more protected from gout [2]. A meta-analysis of the risk of coronary heart disease also showed that coffee consumption was associated with lower risks for coronary heart disease in women than in men [16]. A recent review summarized the sex-dependent differences in several neurological and psychiatric disorders and used estimated caffeine consumption data to compare the association between these disorders [43]. Caffeine is more effective in women than in men for improving depression and Parkinson’s disease, and caffeine enhances anxiety in men more than in women.

References

- Chu, Y.F. Coffee: Emerging Health Effects and Disease Prevention. In Coffee: Emerging Health Effects and Disease Prevention; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012.

- Hou, C.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, W.; Han, X.; Yang, H.; Ying, Z.; Hu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qu, Y.; Fang, F.; et al. Medical conditions associated with coffee consumption: Disease-trajectory and comorbidity network analyses of a prospective cohort study in UK Biobank. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 730–740.

- Van Dam, R.M.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C. Coffee, Caffeine, and Health. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 369–378.

- Kim, S.A.; Tan, L.J.; Shin, S. Coffee Consumption and the Risk of All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in the Korean Population. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, P2221–P2232.e4.

- Di Maso, M.; Boffetta, P.; Negri, E.; la Vecchia, C.; Bravi, F. Caffeinated Coffee Consumption and Health Outcomes in the US Population: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis and Estimation of Disease Cases and Deaths Avoided. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1160–1176.

- Liu, D.; Li, Z.H.; Shen, D.; Zhang, P.D.; Song, W.-Q.; Zhang, W.-T.; Huang, Q.-M.; Chen, P.L.; Zhang, X.R.; Mao, C. Association of Sugar-Sweetened, Artificially Sweetened, and Unsweetened Coffee Consumption With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Large Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 909–917.

- Lin, P.; Liang, Z.; Wang, M. Caffeine consumption and mortality in populations with different weight statuses: An analysis of NHANES 1999–2014. Nutrition 2022, 102, 111731.

- Wang, T.; Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, D. Association between coffee consumption and functional disability in older US adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 695–702.

- Feng, J.; Wang, J.; Jose, M.; Seo, Y.; Feng, L.; Ge, S. Association between Caffeine Intake and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: An Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2014 Database. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 901–912.

- Doepker, C.; Movva, N.; Cohen, S.S.; Wikoff, D.S. Benefit-risk of coffee consumption and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and disability adjusted life year analysis. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2022, 170, 113472.

- Shin, S.; Lee, J.E.; Loftfield, E.; Shu, X.O.; Abe, S.K.; Rahman, M.S.; Saito, E.; Islam, M.R.; Tsugane, S.; Sawada, N.; et al. Coffee and tea consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease and cancer: A pooled analysis of prospective studies from the Asia Cohort Consortium. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 51, 626–640.

- Torres-Collado, L.; Compañ-Gabucio, L.M.; González-Palacios, S.; Notario-Barandiaran, L.; Oncina-Cánovas, A.; Vioque, J.; García-de la Hera, M. Coffee Consumption and All-Cause, Cardiovascular, and Cancer Mortality in an Adult Mediterranean Population. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1241.

- Fraser, G.E.; Cosgrove, C.M.; Mashchak, A.D.; Orlich, M.J.; Altekruse, S.F. Lower rates of cancer and all-cause mortality in an Adventist cohort compared with a US Census population. Cancer 2020, 126, 1102–1111.

- Shan, Z.; Wang, F.; Li, Y.; Baden, M.Y.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Wang, D.D.; Sun, Q.; Rexrode, K.M.; Rimm, E.B.; Qi, L.; et al. Healthy Eating Patterns and Risk of Total and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023; ahead of print.

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y. Consumption of coffee and tea with all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 449.

- Park, Y.; Cho, H.; Myung, S.K. Effect of Coffee Consumption on Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Am. J. Cardiol. 2023, 186, 17–29.

- Cornelis, M.C.; van Dam, R.M. Habitual coffee and tea consumption and cardiometabolic biomarkers in the UK biobank: The role of beverage types and genetic variation. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 2772–2788.

- Zhou, A.; Hyppönen, E. Long-term coffee consumption, caffeine metabolism genetics, and risk of cardiovascular disease: A prospective analysis of up to 347,077 individuals and 8368 cases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 509–516.

- Teramoto, M.; Yamagishi, K.; Muraki, I.; Tamakoshi, A.; Iso, H. Coffee and Green Tea Consumption and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality Among People With and Without Hypertension. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 12, e026477.

- Borghi, C. Coffee and blood pressure: Exciting news! Blood Press. 2022, 31, 284–287.

- Ruggiero, E.; di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; Persichillo, M.; de Curtis, A.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L.; Bonaccio, M. Daily Coffee Drinking Is Associated with Lower Risks of Cardiovascular and Total Mortality in a General Italian Population: Results from the Moli-sani Study. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 395–404.

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, S.; Li, W.D.; Wang, Y. Consumption of coffee and tea and risk of developing stroke, dementia, and poststroke dementia: A cohort study in the UK Biobank. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003830.

- Tran, A.; Zhang, C.Y.; Cao, C. The Role of Coffee in the Therapy of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Park. 2016, 5, 203.

- Herden, L.; Weissert, R. The Impact of Coffee and Caffeine on Multiple Sclerosis Compared to Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 133.

- Wang, M.; Cornelis, M.C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Lian, X. Mendelian randomization study of coffee consumption and age at onset of Huntington’s disease. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5615–5618.

- Fisicaro, F.; Lanza, G.; Pennisi, M.; Vagli, C.; Cantone, M.; Pennisi, G.; Ferri, R.; Bella, R. Moderate Mocha Coffee Consumption Is Associated with Higher Cognitive and Mood Status in a Non-Demented Elderly Population with Subcortical Ischemic Vascular Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 536.

- Yahalom, G.; Rigbi, A.; Israeli-Korn, S.; Krohn, L.; Rudakou, U.; Ruskey, J.A.; Benshimol, L.; Tsafnat, T.; Gan-Or, Z.; Hassin-Baer, S.; et al. Age at Onset of Parkinson’s Disease Among Ashkenazi Jewish Patients: Contribution of Environmental Factors, LRRK2 p.G2019S and GBA p.N370S Mutations. J. Park. Dis. 2010, 10, 1123–1132.

- Chan, L.; Hong, C.T.; Bai, C.H. Coffee consumption and the risk of cerebrovascular disease: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 380.

- Kolb, H.; Martin, S.; Kempf, K. Coffee and lower risk of type 2 diabetes: Arguments for a causal relationship. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1144.

- Imamura, F.; Schulze, M.B.; Sharp, S.J.; Guevara, M.; Romaguera, D.; Bendinelli, B.; Salamanca-Fernández, E.; Ardanaz, E.; Arriola, L.; Aune, D.; et al. Estimated Substitution of Tea or Coffee for Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Was Associated with Lower Type 2 Diabetes Incidence in Case-Cohort Analysis across 8 European Countries in the EPIC-InterAct Study. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1985–1993.

- Hang, D.; Kværner, A.S.; Ma, W.; Hu, Y.; Tabung, F.K.; Nan, H.; Hu, Z.; Shen, H.; Mucci, L.A.; Chan, A.T.; et al. Coffee consumption and plasma biomarkers of metabolic and inflammatory pathways in US health professionals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 635–647.

- Komorita, Y.; Iwase, M.; Fujii, H.; Ohkuma, T.; Ide, H.; Jodai-Kitamura, T.; Yoshinari, M.; Oku, Y.; Higashi, T.; Nakamura, U.; et al. Additive effects of green tea and coffee on all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Fukuoka Diabetes Registry. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8, e001252.

- Wang, S.; Han, Y.; Zhao, H.; Han, X.; Yin, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, X. Association between Coffee Consumption, Caffeine Intake, and Metabolic Syndrome Severity in Patients with Self-Reported Rheumatoid Arthritis: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2018. Nutrients 2022, 15, 107.

- Kennedy, O.J.; Fallowfield, J.A.; Poole, R.; Hayes, P.C.; Parkes, J.; Roderick, P.J. All coffee types decrease the risk of adverse clinical outcomes in chronic liver disease: A UK Biobank study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 970.

- Coelho, M.; Patarrão, R.S.; Sousa-Lima, I.; Ribeiro, R.T.; Meneses, M.J.; Andrade, R.; Mendes, V.M.; Manadas, B.; Raposo, J.F.; Macedo, M.P.; et al. Increased Intake of Both Caffeine and Non-Caffeine Coffee Components Is Associated with Reduced NAFLD Severity in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2022, 15, 4.

- Yuan, S.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Fan, R.; Arsenault, B.; Gill, D.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Zheng, J.S.; Larsson, S.C. Lifestyle and metabolic factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Mendelian randomization study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 37, 723–733.

- Yang, J.; Tobias, D.K.; Li, S.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Ley, S.H.; Hinkle, S.N.; Qian, F.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Bao, W.; et al. Habitual coffee consumption and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes in individuals with a history of gestational diabetes—A prospective study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 1693–1703.

- Lee, H.J.; Park, J.I.; Kwon, S.O.; Hwang, D.D. Coffee consumption and diabetic retinopathy in adults with diabetes mellitus. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3547.

- Barré, T.; Fontaine, H.; Pol, S.; Ramier, C.; Di Beo, V.; Protopopescu, C.; Marcellin, F.; Bureau, M.; Bourlière, M.; Dorival, C.; et al. Metabolic Disorders in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Coffee as a Panacea? (ANRS CO22 Hepather Cohort). Antioxidants 2022, 11, 379.

- Ng, S.C.; Tang, W.; Leong, R.W.; Chen, M.; Ko, Y.; Studd, C.; Niewiadomski, O.; Bell, S.; Kamm, M.A.; de Silva, H.J.; et al. Environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease: A population-based case-control study in Asia-Pacific. Gut 2015, 64, 1063–1071.

- Cohen, A.B.; Lee, D.; Long, M.D.; Kappelman, M.D.; Martin, C.F.; Sandler, R.S.; Lewis, J.D. Dietary patterns and self-reported associations of diet with symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 1322–1328.

- Güngördük, K.; Özdemir, İ.A.; Güngördük, Ö.; Gülseren, V.; Gokçü, M.; Sancı, M. Effects of coffee consumption on gut recovery after surgery of gynecological cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 216, 145.e1–145.e7.

- Jee, H.J.; Lee, S.G.; Bormate, K.J.; Jung, Y.S. Effect of Caffeine Consumption on the Risk for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders: Sex Differences in Human. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3080.

- Lu, M.Y.; Cheng, H.Y.; Lai, J.C.; Chen, S.J. The Relationship between Habitual Coffee Drinking and the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Taiwanese Adults: Evidence from the Taiwan Biobank Database. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1867.

More