Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Jessie Wu and Version 2 by Jessie Wu.

microRNAs (MiRNAs) are small endogenous single-stranded RNAs (20 to 22 nucleotides) that are involved in post-transcriptional gene silencing in eukaryotes. They allow the downregulation of target genes by specifically triggering the degradation of their messenger RNAs (mRNAs) or by inhibiting their translation. Most plant species have several hundred annotated miRNA genes. miRNA primary transcripts were recently shown to contain functional short Open Reading Frames producing regulatory peptides called miRNA-encoded Peptides (miPEPs).

- miPEP

- plant

- animal

1. miRNA-Encoded Peptide Discovery

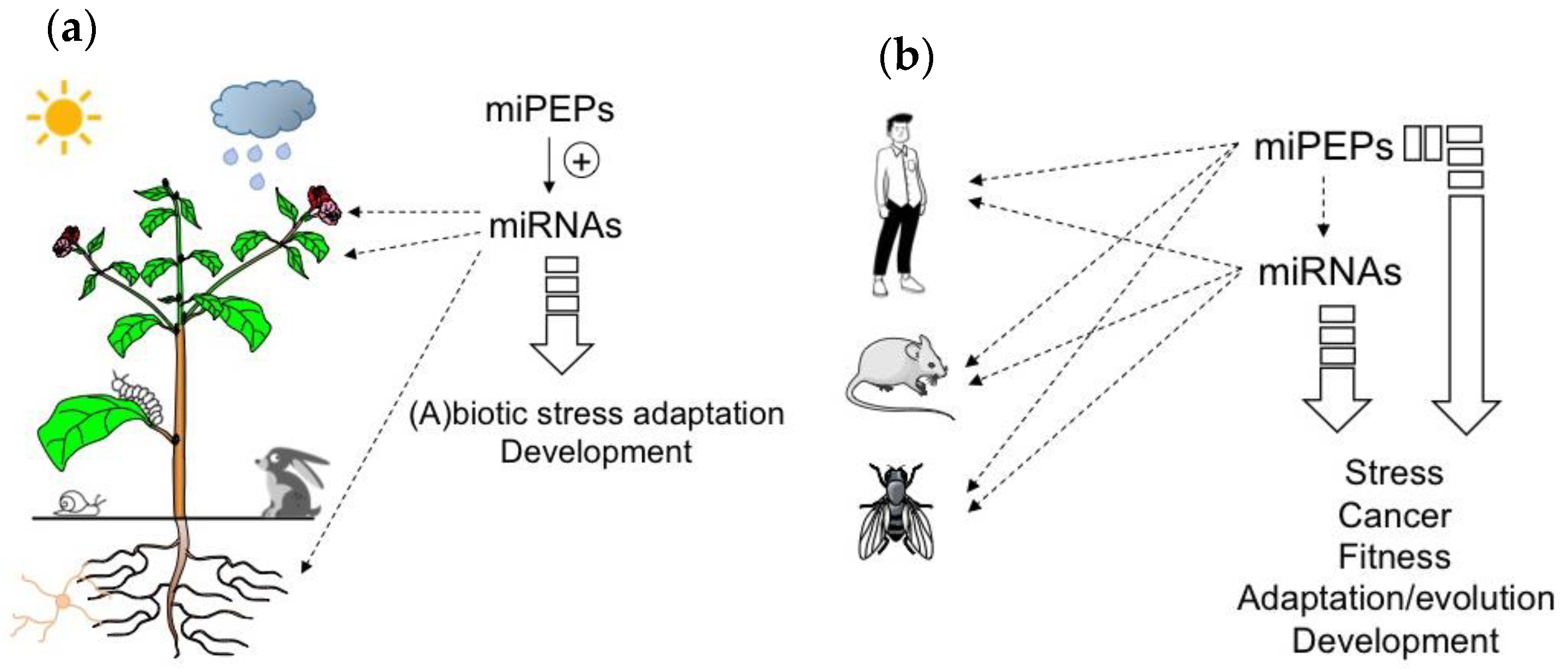

Peptides are known to be involved in many processes including developmental regulation, acclimation to abiotic stress, and defense against pathogens [1][2][3][4][5] (Figure 1). The majority of known regulatory peptides in plants are derived from precursor proteins [6]. However, peptides that are directly translated from sORFs have also been reported [1][3]. Among them, those located in the 5’ region of primary transcripts of miRNAs (pri-miRNAs), termed miRNA-encoded peptides (miPEPs), have recently received more attention [7][8][9]. Indeed, based on in-house and existing RACE-PCR-based annotations of pri-miRNAs of M. truncatula and A. thaliana, Lauressergues and colleagues (2015) performed an in silico analysis revealing the presence of at least one putative sORF in the 5’ region of MtmiR171b and AtmiR165a pri-miRNAs [10]. The functionality of these sORFs was validated for the first time in this study using A. thaliana and M. truncatula as model plants. Indeed, in both cases, the presence of endogenously expressed miPEPs was visualized by western blot and/or immunofluorescence using specific antibodies [10].

Figure 1. MicroRNA-encoded peptides (miPEPs) regulate many biological functions both in plants and animals. (a) The ability of plant miPEPs to positively regulate the expression of their respective pri-miRNAs is described for several miPEPs and plant species. (b) Conversely, in animals, the regulation of pri-miRNAs by miPEPs is less clear. MiPEPs frequently act independently.

Since their discovery, the existence of miPEPs has been extended to various pri-miRNAs in several plant species as listed in Table 1 [11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22].

Table 1. List of miPEPs (and their embedded miRs) described in the literature (and miRbase) both in plants and animals.

| Organism | MiPEP (miR) |

MiPEP Size | In Vivo miPEP Detection | Effect on the Corresponding Pri-miRNA | Regulation of miRNA Targets |

Regulated Biological Functions | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plants | |||||||

| Arabidospsis thaliana | AtmiPEP165a (ath-miR165a) |

18 | GUS reporter gene expression and wb | Upregulation | Downregulation of HD-ZIP III PHAVOLUTA, PHABOLUSA, REVOLUTA | Stimulation of main root growth; Acceleration of the inflorescence stem appearance and of the flowering time; Inhibitory effect on total root growth | [10][11][12] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AtmiPEP858a (ath-amiR858a) |

44 | GUS reporter gene expression and wb | Upregulation | Downregulation of MYB transcription factor AtMYB12 | Flavonoid biosynthesis and plant development | [13] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AtmiPEP164b (ath-miR164b) |

29 | N/A | Upregulation | Downregulation of NAC1, NAC4, NAC5, CUC1 and CUC2 | Inhibitory effect on total root growth | [12] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AtmiPEP397a (ath-miR397a) |

7 | N/A | Upregulation | Downregulation of LAC2, LAC4 and LAC17 | Stimulation of total root growth | [12] |

| Dimocarus Longan Lour | N/A | 50 | N/A | Upregulation | Downregulation of HD-ZIP IIIATHB15 | Embryogenesis | [14] |

| Glycine max | GmmiPEP172c (gma-miR172c) |

16 | N/A | Upregulation | Downregulation of AP2 transcription factor NODULE NUMBER CONTROL 1 | Increase in nodule number | [15] |

| Lotus japonicus | LjmiPEP171b (lja-miR171b) |

22 | N/A | Upregulation | N/A | Increase in mycorrhization rate | [16] |

| Medicago truncatula | MtmiPEP171b (mtr-miR171b) |

20 | GUS reporter gene expression and wb | Upregulation | Upregulation of GRAS transcription factor LOST MERISTEMS 1 (LOM1) | Reduction of lateral root development and increase in mycorrhization rate | [10][16] |

| Medicago truncatula | MtmiPEP171a (mtr-miR171a) |

10 | N/A | N/A | Downregulation of LOM1 | Decrease in mycorrhization rate | [16] |

| Medicago truncatula | MtmiPEP171c (mtr-miR171c) |

7 | N/A | N/A | Downregulation of LOM1 | Decrease in mycorrhization rate | [16] |

| Medicago truncatula | MtmiPEP171d (mtr-miR171d) |

6 | N/A | N/A | Downregulation of LOM1 | Decrease in mycorrhization rate | [16] |

| Medicago truncatula | MtmiPEP171e (mtr-miR171e) |

23 | N/A | N/A | Downregulation of LOM1 | Decrease in mycorrhization rate | [16] |

| Medicago truncatula | MtmiPEP171f (mtr-miR171f) |

5 | N/A | N/A | Downregulation of LOM1 | Decrease in mycorrhization rate | [16] |

| Oryza sativa | OsmiPEP171i (osa-miR171i) |

31 | N/A | Upregulation | N/A | Increase in mycorrhization rate | [16] |

| Solanum lycopersicum | SlmiPEP171e (slymiR171e) |

19 | N/A | Upregulation | N/A | Increase in mycorrhization rate | [16] |

| Vitiis vinifera | VvimiPEP171d1 (vvi-MIR171d1 *) |

7 | GUS reporter gene expression | Upregulation | Downregulation of scarecrow-like VvSCL27 | Adventitious root formation | [17] |

| Vitis vinifera | VvimiPEP164c (vvi-miR164c) |

16 | N/A | Upregulation | Downregulation of VvMYBPA1 grapevine transcription factor | Inhibition of proanthocyanidin synthesis and stimulates anthocyanin accumulation | [18] |

| Vitis vinifera | VvimiPEP172b (vvi-miR172b) |

16 | N/A | Upregulation | Downregulation of VvRAP2-7-1 | Increase in cold tolerance in grapevine | [19] |

| Vitis vinifera | VvimiPEP3635b (vvi-MIR3635b *) |

11 | N/A | Upregulation | Downregulation of VvENT3 | Increase in cold tolerance in grapevine | [19] |

| Barbarea vulgaris | BvmiPEP164b (bv-miR164b *) |

8 | N/A | Upregulation | Downregulation of NAC1, NAC4, NAC5, CUC1 and CUC2 | Inhibitory effect on main root growth and foliar surface | [12] |

| Brassica oleacera | BomiPEP397a (bo-miR397a *) |

10 | N/A | Upregulation | Downregulation of LAC2, LAC4 and LAC17 | Stimulation of main root growth and foliar surface | [12] |

| Brassica rapa | BrmiPEP156a (br-miR156a) |

33 | TAMRA- labeled peptide |

Upregulation | N/A | Moderate stimulation of main root growth | [20] |

| Animals | |||||||

| Human | miPEP200a (hsa-miR-200a) |

187 | wb; HA fused peptide over-expressed in cells | No regulation | Inhibit the expression of vimentin in cancer cells | Inhibition of the migration of prostate cancer cells | [23][24] |

| Human | miPEP200b (hsa-miR-200b) |

54 | wb; HA fused peptide over-expressed in cells | N/A | Inhibit the expression of vimentin in cancer cells | Inhibition of the migration of prostate cancer cells | [23] |

| Human | miPEP155 (hsa-miR-155) |

17 | EGFP-fused ORF | No regulation | No regulation | Suppression of autoimmune inflammation by modulating antigen presentation | [24][25] |

| Human | miPEP497 (hsa-miR-497) |

21 | N/A | No regulation | No regulation | N/A | [24] |

| Human | miPEP22 (hsa-miR-22) |

57 | wb | N/A | N/A | Tumor suppressor | [26] |

| Human | miPEP133 (hsa-miR-34a) |

133 | wb | Up-regulation | N/A | Increase in p53 transcriptional activity by disrupting mitochondrial function | [27] |

| Human | MISTRAV or MOCCI (hsa-miR-147b) |

83 | Wb; Immuno- fluorescence of over-expressed peptide |

No regulation | N/A | Viral stress response, inflammation and immunity | [28][29] |

| Drosophila melanogaster | MSAmiP (dme-miR-iab-8) |

9 to 20 | EGFP-fused ORF | No regulation | N/A | Involved in sperm competition | [30] |

| Drosophila melanogaster | DmmiPEP8 (dme-miR- 8) |

71 | wb | No regulation | No regulation | Wing size reduction | [31] |

| Mus musculus | MmmiPEP31 (mmu-miR-31) |

44 | EGFP-fused ORF and wb | down-regulation | N/A | Suppression of EAE by promoting the differentiation of Treg cells | [32] |

*: miR not present in miRbase.

At the same time, the question of whether miPEPs exist in animals has arisen. The first description came from Razooky and co-workers (2017), who identified a miPEP called C17orf91 expressed from the pri-miRNA22 host gene [26]. MiPEP C17orf91 was upregulated upon viral infection but no associated function was reported. Later, several pri-miRNAs encoding miR34a, miR31, miR155, miR147b in mammals and miR8 and iab8 in Drosophila were described as capable of expressing miPEPs [25][27][28][29][30][31][32].

While it remains to be clarified in animals, several studies performed in plants on different miRNA genes have reported that the first ORF after the transcription start site is preferentially translated into a miPEP [10][13][17][33]. No common signature has been found among these different sORF-encoded peptides. However, so far, in plants, all tested miPEPs have been shown to act as an activator of their cognate miRNA expression contrasting with animals where only effects of sORF were detected [24][31][34].

2. miRNA-Encoded Peptide Functions

2.1. In Plants

Several pieces of evidence suggest that miPEPs activate the expression of their miRNA genes. Indeed, the overexpression of AtmiPEP165a in a heterologous species (Nicotiana benthamiana), or the application of its synthetic version, increased the expression of both its corresponding pri-miRNA and the mature miRNA, and correlatively decreased the expression of miRNA target genes in A. thaliana. Similarly, the M. truncatula miPEP171b was able to increase its Mtpri-miR171b expression, suggesting that the function of miPEPs is conserved and not limited to a few species [10]. The positive effect of miPEPs on the accumulation of their respective pri-miRNAs was inhibited by cordycepin, a transcription inhibitor, suggesting that miPEPs induce this accumulation by increasing the transcription of their corresponding miRNA genes [10].

Due to the positive feedback that miPEPs exert on their corresponding pri-miRNAs in plants, miPEPs can be expected to exhibit diverse biological functions ranging from plant development to beneficial plant-microbial interactions or stress resistance, and could thus be considered as a natural alternative to pesticides and chemical fertilizers (Figure 1a).

A study performed on grapevine was recently published in this context [17]. MiRNA171 family members are known to target genes involved in the formation and development of roots in different plants [10][35]. Chen and colleagues found that VviMIR171 gene members were specifically expressed during the formation and development of grapevine (Vitis vinifera) adventitious roots [17]. When VvimiR171d was overexpressed in A. thaliana, the plants displayed shorter primary roots, higher lateral root density, and earlier adventitious root development compared to wild-type (WT) plants. An in silico analysis predicted three putative sORFs in the 5’ region of Vvipri-miRNA171d. Their respective transient overexpression in grape tissue culture plantlets showed that only the first pri-miRNA sORF enabled an increase in VvimiR171d expression. In addition, when a construct containing the region from the VvimiR171d promoter to the ATG start site of this sORF fused to the GUS gene was expressed in N. benthamiana leaves or grape tissue culture plantlets, GUS activity was observed. These data demonstrate that this sORF encodes a peptide, which was named VvimiPEP171d1. Similar to what was previously described, when grape tissue culture plantlets were treated with synthetic VvimiPEP171d1, VvimiR171d expression specifically increased while the expression of miRNA target genes correlatively decreased. In addition, when grape plantlets were grown on a medium containing synthetic VvimiPEP171d1, the number of adventitious roots significantly increased, indicating that the miPEP is able to regulate the formation and development of grapevine adventitious roots. This property appears specific to grapevines since VvimiPEP171d1 had no effect on A. thaliana roots.

More recently, the same group characterized the function of two other miPEPs in grapevines, namely VvimiPEP172b and VvimiPEP3635b [19]. First, the authors identified VvimiRNAs in grape tissue culture plantlets, whose expressions were modified during cold stress (4°C). They then selected VvimiR172b and VvimiR3635b for further analysis. Using an in silico approach, they identified six and four putative sORFs, respectively, in the 5’ region of the corresponding pre-miRNAs. They transiently expressed these sORFs in tissue culture plantlets independently and found that one ORF from each pre-miRNA was biologically active as it was able to increase the expression of its nascent pri-miRNA. They synthesized the corresponding miPEPs and, interestingly, their external application on grape tissue culture plantlets improved their tolerance to cold.

Another example illustrating the potentiality of miPEPs came from the study of the effect of AtmiPEP858a on Arabidopsis development [13]. AtmiR858 had previously been shown to downregulate the expression of different transcription factors such as AtMYB11, AtMYB12, and AtMYB11, which regulate the phenylpropanoid pathway that sources the metabolites required for the biosynthesis of lignin and the production of many other important compounds such as flavonoids, coumarins, and lignans [36]. In addition, AtmiR858 modifies plant development by increasing root growth and accelerating flowering. By analyzing the region upstream of Atpre-miR858a, the authors found three putative sORFs, of which one was shown to be translated in planta using reporter gene fusion assays and western blot experiments. This peptide, named AtmiPEP858a, increased the expression of both Atpri-miR858a and mature AtmiR858 when exogenously applied to Arabidopsis seedlings; this also correlated with a downregulation of the expression of AtMYB12 and its target genes, and phenotypically with an increase in root length. The effect of AtmiPEP858a was then confirmed via genetic approaches using both transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing the miPEP and Cas9-edited AtmiPEP858a mutant plants. Thus, AtmiPEP858a-overexpressing plants exhibited longer main roots than WT plants, while edited mutant lines showed an inverted phenotype. Interestingly, the exogenous treatment of AtmiPEP858a-edited mutant plants with AtmiPEP858a complemented this phenotype. Compared to WT plants, AtmiPEP858a-overexpressing plants exhibited a reduction in anthocyanin accumulation as well as an increase in lignin content, together with enhanced expression of lignin biosynthesis genes. The reciprocal phenotype was observed in AtmiPEP858a-edited plants [13]. Very recently, the same group showed that a disulfated pentapeptide, named Phytosulfokine4 (PSK4), plays a key role in the growth and development of AtmiR858-dependent Arabidopsis, through auxin [22]. Interestingly, AtmiPEP858a positively regulates the expression of PSK4 via AtmiR858a. The expression of AtmiR858a and PSK4 is also positively regulated by the AtMYB3 transcription factor through the direct binding of AtMYB3 to its target promoters. AtMYB3, whose expression is regulated by AtmiPEP858a/AtmiR858a, is a key component in AtmiPEP858a/AtmiR858a-PSK4-dependent plant growth and development [22]. Concomitantly to this study, the same authors showed that light directly regulates AtmiPEP858a accumulation in Arabidopsis and is necessary for AtmiPEP858a action. This light-dependent miPEP regulation requires the shoot-to-root mobile, light-mediated transcription factor, AtHY5 [37]. Overall, the data place AtmiPEP858a at the crossroads of several biological processes, most likely through the regulation of its corresponding miRNA.

MiPEPs can also modulate rhizospheric plant-microorganism interactions. For instance, an exogenous application of GmmiPEP172c specifically increases nodule numbers in soybean (Glycine max) when inoculated with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens and leads to an increase in GmmiR172c transcripts [15]. These results are in agreement with those previously observed by Wang et al., (2014), which show that GmmiR172c overexpression positively regulates nodulation in soybean through the repression of its target gene—the Apetala 2 (GmAP2) transcription factor Nodule Number Control 1 (GmNNC1)—which directly binds to the promoter of Early Nodulin 40 (GmENOD40) to repress its transcription [38]. Another example is the role played by MtmiPEP171b in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in M. truncatula [16]. Unlike other members of the MtmiPEP171 family, MtmiPEP171b stimulates arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis and positively regulates the expression of its corresponding MtmiR171b as well as the expression of MtmiR171b target MtLOM1 (Lost Meristems 1). MtmiR171b is specifically expressed in root cells containing arbuscules and protects MtLOM1 from being silenced by other MtmiR171 members through its mismatched cleavage site [16].

2.2. In Animals

With the miPEP description within miR34a, miR31, miR155, and miR147b genes in mammals and miR8 and iab8 genes in Drosophila (see above), it is now well established that pri-miRNAs can encode miPEPs in animal cells and, for some of them, their function and biology have even been documented. However, whether and how miPEPs regulate their corresponding pri-miRNA expression remains contradictory. To date, the only example in the animal literature describing a positive effect of a miPEP on the expression of its corresponding pri-miRNA is that of HsmiPEP133. HsmiPEP133 is a 133 amino acid peptide encoded by Hspri-miR34a. HsmiPEP133 induces the expression of Hspri-miR34a/miR34a which leads to the downregulation of HsmiR34a-targeted genes [27]. HsmiPEP133 is expressed in various healthy tissues but is downregulated in cancer cell lines and tumors. The overexpression of HsmiPEP133 indicates that the peptide acts as a human tumor suppressor in cellulo and in vivo by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting the migration and invasion of cancer cells. However, HsMiPEP133 is mainly localized in mitochondria and not in nuclei as reported for plant miPEPs. It modulates a yet-to-be-defined signaling cascade that increases p53 transcriptional activity by disrupting mitochondrial function. Since miR34a is a direct target gene of the transcription factor p53, the latter upregulates both HsmiPEP133 and its corresponding HsmiR34a, most likely among a plethora of other p53 target genes. In addition, the authors showed that the positive feedback regulation of HsmiR34a by HsmiPEP133 can occur in both a p53-dependent and -independent manner, suggesting that miPEP133 can act through other molecular players [27]. More recently, Zhou and colleagues (2022) showed, in mice (Mus musculus), that MmmiPEP31 promotes the differentiation of regulatory T cells by repressing the expression of MmmiR31 in a sequence-dependent manner [32]. Interestingly, the authors showed that miPEP31 enters cells spontaneously and localizes to nuclei. The authors also demonstrate that miPEP31 negatively controls the expression of miR31, providing the first evidence that a miPEP can negatively control the expression of a miRNA gene. However, the mechanism involved seems different from that of miPEP133. Indeed, MmmiPEP31 binds to the Mmpri-miR31 promoter, induces the deacetylation of histone H3K27 (likely through the recruitment of a cofactor), and competes for the binding of an unknown transcription factor [32].

Although these two examples show that mammalian miPEPs are able to regulate their corresponding pri-miRNAs, either positively or negatively, animal miPEPs likely play other functions, which remain to be identified. The mechanism described in plants is probably not a general mechanism conserved in animal pri-miRNAs. Indeed, HsmiPEP200a, HsmiPEP155, HsmiPEP497, HsMOCCI/MISTRAV, DmmiPEP8 and DmMSAmiP do not reveal any effect on their corresponding pri-miRNA [24][25][28][29][30][31]. Furthermore, these miPEPs exhibit regulatory and biological functions uncoupled from their miRNA activity, acting either antagonistically to [25], in parallel with [31], or independently of [30], the miRNA pathway.

To conclude this part, the studies described above show that while positive feedback regulation has been found in all plant miRNA genes studied so far, diverse miPEP effects have been reported in different animal model systems (Figure 1b), indicating that miPEP-dependent positive feedback regulation of miRNA genes is not a general mechanism that can be extended to all organisms.

References

- Hellens, R.P.; Brown, C.M.; Chisnall, M.A.W.; Waterhouse, P.M.; Macknight, R.C. The emerging world of small ORFs. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 317–328.

- Oh, E.; Seo, P.J.; Kim, J. Signaling peptides and receptors coordinating plant root development. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 337–351.

- Choi, S.W.; Kim, H.W.; Nam, J.W. The small peptide world in long noncoding RNAs. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1853–1864.

- Segonzac, C.; Monaghan, J. Modulation of plant innate immune signaling by small peptides. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2019, 51, 22–28.

- Takahashi, F.; Hanada, K.; Kondo, T.; Shinozaki, K. Hormone-like peptides and small coding genes in plant stress signaling and development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2019, 51, 88–95.

- Tavormina, P.; De Coninck, B.; Nikonorova, N.; De Smet, I.; Cammue, B.P. The plant peptidome: An expanding repertoire of structural features and biological functions. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 2095–2118.

- Waterhouse, P.M.; Hellens, R.P. Plant biology: Coding in non-coding RNAs. Nature 2015, 520, 41–42.

- Julkowska, M. Small but powerful: MicroRNA-derived peptides promote grape adventitious root formation. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 429–430.

- Prasad, A.; Sharma, N.; Prasad, M. Noncoding but coding: Pri-miRNA into the action. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 204–206.

- Lauressergues, D.; Couzigou, J.M.; Clemente, H.S.; Martinez, Y.; Dunand, C.; Bécard, G.; Combier, J.P. Primary transcripts of microRNAs encode regulatory peptides. Nature 2015, 520, 90–93.

- Ormancey, M.; Le Ru, A.; Duboé, C.; Jin, H.; Thuleau, P.; Plaza, S.; Combier, J.P. Internalization of miPEP165a into Arabidopsis roots depends on both passive diffusion and endocytosis-associated processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2266.

- Ormancey, M.; Guillotin, B.; San Clemente, H.; Thuleau, P.; Plaza, S.; Combier, J.P. Use of microRNA-encoded peptides to improve agronomic traits. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1687–1689.

- Sharma, A.; Badola, P.K.; Bhatia, C.; Sharma, D.; Trivedi, P.K. Primary transcript of miR858 encodes regulatory peptide and controls flavonoid biosynthesis and development in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1262–1274.

- Zhang, Q.L.; Su, L.Y.; Zhang, S.T.; Xu, X.P.; Chen, X.H.; Li, X.; Jiang, M.Q.; Huang, S.Q.; Chen, Y.K.; Zhang, Z.H.; et al. Analyses of microRNA166 gene structure, expression, and function during the early stage of somatic embryogenesis in Dimocarpus longan Lour. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 147, 205–214.

- Couzigou, J.M.; André, O.; Guillotin, B.; Alexandre, M.; Combier, J.P. Use of microRNA-encoded peptide miPEP172c to stimulate nodulation in soybean. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 379–381.

- Couzigou, J.M.; Lauressergues, D.; André, O.; Gutjahr, C.; Guillotin, B.; Bécard, G.; Combier, J.P. Positive gene regulation by a natural protective miRNA enables arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 106–112.

- Chen, Q.J.; Deng, B.H.; Gao, J.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Chen, Z.L.; Song, S.R.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.P.; Xu, W.P.; Zhang, C.X.; et al. A miRNA-encoded small peptide, Vvi-miPEP171d1, regulates adventitious root formation. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 656–670.

- Vale, M.; Rodrigues, J.; Badim, H.; Gerós, H.; Conde, A. Exogenous application of non-mature miRNA-encoded miPEP164c inhibits proanthocyanidin synthesis and stimulates anthocyanin accumulation in grape berry cells. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 706679.

- Chen, Q.J.; Zhang, L.P.; Song, S.R.; Wang, L.; Xu, W.P.; Zhang, C.X.; Wang, S.P.; Liu, H.F.; Ma, C. Vvi-miPEP172b and vvi-miPEP3635b increase cold tolerance of grapevine by regulating the corresponding MIRNA genes. Plant Sci. 2022, 5, 111450.

- Erokhina, T.N.; Ryazantsev, D.Y.; Samokhvalova, L.V.; Mozhaev, A.A.; Orsa, A.N.; Zavriev, S.K.; Morozov, S.Y. Activity of chemically synthesized peptide encoded by the miR156A precursor and conserved in the Brassicaceae family plants. Biochemistry 2021, 86, 551–562.

- Ram, M.K.; Mukherjee, K.; Pandey, D.V. Identification of miRNA, their targets and miPEPs in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Comp. Biol. Chem. 2019, 83, 107100.

- Badola, P.K.; Sharma, A.; Gautam, H.; Trivedi, P.K. MicroRNA858a, its encoded peptide, and phytosulfokine regulate Arabidopsis growth and development. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 1397–1415.

- Fang, J.; Morsalin, S.; Rao, V.N.; Reddy, E.S.P. Decoding of non-coding DNA and non-coding RNA: Pri-Micro RNA-encoded novel peptides regulate migration of cancer cells. J. Pharm. Sci. Pharmacol. 2017, 3, 23–27.

- Prel, A.; Dozier, C.; Combier, J.P.; Plaza, S.; Besson, A. Evidence that regulation of pri-miRNA/miRNA expression is not a general rule of miPEPs function in Humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3432.

- Niu, L.; Lou, F.; Sun, Y.; Sun, L.; Cai, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Bai, J.; et al. A micropeptide encoded by lncRNA MIR155HG suppresses autoimmune inflammation via modulating antigen presentation. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz2059.

- Razooky, B.S.; Obermayer, B.; O’May, J.B.; Tarakhovsky, A. Viral infection identifies micropeptides differentially regulated in smORF-containing lncRNAs. Genes 2017, 8, 206.

- Kang, M.; Tang, B.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, K.; Wang, R.; Jiang, Z.; Bi, F.; Patrick, D.; Kim, D.; et al. Identification of miPEP133 as a novel tumor-suppressor microprotein encoded by miR-34a pri-miRNA. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 143.

- Sorouri, M.; Chang, T.; Jesudhasan, P.; Pinkham, C.; Elde, N.C.; Hancks, D.C. Signatures of host-pathogen evolutionary conflict reveal MISTR-A conserved MItochondrial STress Response network. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3001045.

- Lee, C.Q.E.; Kerouanton, B.; Chothani, S.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Mantri, C.K.; Hock, D.H.; Lim, R.; Nadkarni, R.; Huynh, V.T.; et al. Coding and non-coding roles of MOCCI (C15ORF48) coordinate to regulate host inflammation and immunity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2130.

- Immarigeon, C.; Frei, Y.; Delbare, S.Y.N.; Gligorov, D.; Machado Almeida, P.; Grey, J.; Fabbro, L.; Nagoshi, E.; Billeter, J.C.; Wolfner, M.F.; et al. Identification of a micropeptide and multiple secondary cell genes that modulate Drosophila male reproductive success. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2001897118.

- Montigny, A.; Tavormina, P.; Duboé, C.; San Clémente, H.; Aguilar, M.; Valenti, P.; Lauressergues, D.; Combier, J.P.; Plaza, S. Drosophila primary microRNA-8 encodes a microRNA-encoded peptide acting in parallel of miR-8. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 118.

- Zhou, H.; Lou, F.; Bai, J.; Sun, Y.; Cai, W.; Sun, L.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yin, Q.; et al. A peptide encoded by pri-miRNA-31 represses autoimmunity by promoting Treg differentiation. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e53475.

- Lauressergues, D.; Ormancey, M.; Guillotin, B.; San Clemente, H.; Camborde, L.; Duboé, C.; Tourneur, S.; Charpentier, P.; Barozet, A.; Jauneau, A.; et al. Characterization of plant microRNA-encoded peptides (miPEPs) reveals molecular mechanisms from the translation to activity and specificity. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110339.

- Dozier, C.; Montigny, A.; Viladrich, M.; Culerrier, R.; Combier, J.P.; Besson, A.; Plaza, S. Small ORFs as new Regulators of pri-miRNAs and miRNAs expression in Human and Drosophila. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5764.

- Wang, L.; Mai, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.C.; Luo, Q.; Yang, H.Q. MicroRNA171c-targeted SCL6-II, SCL6-III, and SCL6-IV genes regulate shoot branching in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 794–806.

- Sharma, D.; Tiwari, M.; Pandey, A.; Bhatia, C.; Sharma, A.; Trivedi, P.K. MicroRNA858 is a potential regulator of phenylpropanoid pathway and plant development. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 944–959.

- Sharma, A.; Badola, P.K.; Gautam, H.; Gaddam, S.R.; Trivedi, P.K. HY5 regulates light-dependent expression and accumulation of miR858a-encoded peptide, miPEP858a. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 589, 204–208.

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zou, Y.; Chen, L.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, F.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Ferguson, B.J.; et al. Soybean miR172c targets the repressive AP2 transcription factor NNC1 to activate ENOD40 expression and regulate nodule initiation. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 4782–4801.

More