Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Yi-Han Chiu and Version 2 by Sirius Huang.

The mechanisms by which immune systems identify and destroy tumors, known as immunosurveillance, have been discussed for decades. However, several factors that lead to tumor persistence and escape from the attack of immune cells in a normal immune system have been found. In the process known as immunoediting, tumors decrease their immunogenicity and evade immunosurveillance. Furthermore, tumors exploit factors such as regulatory T cells, myeloid-derived suppressive cells, and inhibitory cytokines that avoid cytotoxic T cell (CTL) recognition.

- immunogenicity

- tumor antigens

- immunoediting

1. The Sentry of the Immune System: Immunosurveillance

1.1. Tumor Recognition and Rejection by the Immune System

T lymphocytes are essential in antitumor immunity, such as in the surveillance, detection, and destruction of neoplastic cells [1]. CTLs are the most potent effectors and are considered significant drivers in antitumor effects [2][4], and they are activated by dendritic cells (DCs). DCs initiate and maintain the antitumor T cell immunity [3][5]. During tumor initiation, the dying tumor cells release danger signals, such as molecules called damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Upon sensing these signals and capturing tumor cells, DCs undergo maturation, migrate to the draining lymph nodes (dLNs), and present the tumor antigens onto major histocompatibility complex I (MHC I) for presentation to CD8+ T cells [4][20]. These activate the antigen-specific CTLs, which naïve CD8+ T cells differentiate into CTLs and memory CD8+ T cells. The educated CTLs can recognize the antigenic targets expressed on the tumors and secrete cytokines, IFN-γ, perforin, and granzyme, thus performing tumor lytic functions [5][6][6,7]. In addition to priming naïve CD8+ T cells, DCs interact with memory T cells and induce their differentiation into the tumor sites [7][21]. Furthermore, DCs produce IL-12, which triggers IFN-γ release from the CTLs, which in turn enhances CTL activation and functions [8][22]. The close interaction between DCs and CTLs suggests tight T cell–DC cross-talk in the tumor microenvironment (TME).

CTLs exerting antitumor effects rely on the help of other immune cells, such as DCs and helper CD4+ T cells. Helper CD4+ T cells play a prominent role in maintaining CD8+ cytolytic responses and preventing CTL exhaustion [2][9][4,23]. Interestingly, the help signals originating from the CD40 ligand (CD40L) on the helper CD4+ T cells stimulate CD40 on the DCs, which deliver CD4+ T cell-derived help signals to CD8+ T cells and elicit CTL responses [10][24]. During the first antigen priming step, naïve CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells are separately activated by different populations of DCs in the peripheral lymph nodes [11][12][13][25,26,27], where MHC I-expressing cDC1 usually interacts with CD8+ T cells. In contrast, MHC II-expressing cDC2 interacts with CD4+ T cells. Next, in the second priming step, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells interact with the same cDC1, and the help signal occurs [14][15][28,29]. cDC1 engages in cognate interaction with pre-activated CD4+ T cells, which optimizes the cDC1 to relay signals for the differentiation of effector T cells and memory CTLs to pre-activated CD8+ T cells [16][30]. In summary, antigen-specific (pre-activated) CD4+ T cells assist the pre-activated CD8+ T cells in the differentiation into effector T or memory T cells. Helper CD4+ T cells dictate the quality of the CTL differentiation and promote the expansion of antigen-specific CTLs by cytokine signals. CD4+ T cells promote the development of antigen-specific CTLs through the amplification of IL-12 and IL-15 production induced by IFN-γ in DCs [17][18][31,32]. Furthermore, IL-2 signaling promotes CD8 proliferation [19][20][33,34], and the expression of IL-2 receptor α-chain (IL-2Rα) by recently primed CD8+ T cells depends on CD4+ T cells [21][35]. In addition to the assistant roles of CD4+ T cells, the cytolytic activities in antitumor effects of CD4+ T cells have been proposed. CD4+ T cells produce IFN-γ and express granzymes and perforin to kill tumors [22][23][36,37]. Recent studies using RNA sequencing in human cancers have reported cytotoxic characteristics of CD4+ T cells, which express cytolytic molecules such as granzymes, perforin, and granulysin in the tumors and circulation of cancer patients [24][25][26][27][38,39,40,41].

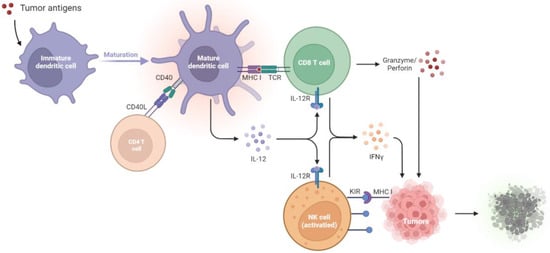

Natural killer (NK) cells are also essential effectors in tumor immunosurveillance. For example, NK cells can be activated by MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A (MICA) and MICB, which are expressed on tumors [28][2]. NK cells directly kill tumor cells by releasing perforin and granzymes [29][3] or trigger cell apoptosis through the ligation of cell death receptor-mediated pathways (FasL/Fas) [30][42]. Healthy cells express high levels of MHC I, which ligates to the killer immunoglobulin-like family inhibitory receptors (KIRs) on NK cells. However, tumors will downregulate MHC I expression to evade CTL-mediated cytotoxicity and simultaneously activate NK cells due to the decreased inhibitory signaling [30][31][42,43] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Tumor suppression by the immune systems during immunosurveillance. Once tumor antigens are captured, immature DCs undergo maturation. The mature DCs present the antigens onto MHC I molecules for presentation to CD8+ T cells. The CD40L on the CD4+ T cell stimulates CD40 on the DCs, which delivers help signals to CD8+ T cells. With the CD40–CD40L interaction, the amplification of IL-12 in DCs promotes the development of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and thus increases the IFN-γ, granzyme, and perforin production to kill tumors. NK cells will be activated by the diminished expression of MHC I on tumors, which relieves the KIR inhibitory signaling and activates the NK cell toxicity towards tumors. CD40L, CD40 ligand; DCs, dendritic cells; IL-12R, IL-12 receptor; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; KIR, killer immunoglobulin-like receptor; MHC I, major histocompatibility complex class I; NK cells, natural killer cells; TCR, T cell receptor.

1.2. Failure of Immunosurveillance Enables Cancer Progression

Accumulating evidence indicates the increased risk of tumor development in immunosuppressed patients, suggesting the crucial antitumor role of intact immunity. Mice with a deficiency in adaptive immunity provide a practical animal model for testing cancer immunosurveillance. In one study, mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) exhibited impaired differentiation of both T and B lymphocytes, and thus 15% of these mice developed T cell lymphomas [32][44]. In another study, RAG2−/− mice, another kind of mice without B and T cells, developed spontaneous intestinal adenomas (50%), intestinal adenocarcinomas (35%), and lung cancers (15%) at the age of 15–16 months [33][45]. In addition to adaptive immunity, NK cells also manifested cancer immunoediting by producing IFN-γ and induced M1 macrophages.

Mice with a deficiency in effector cells, such as T cells and NK cells, usually develop spontaneous cancers with aging. In STAT1-deficient mice, the JAK/STAT1 signaling pathway is down-regulated and thus inhibits type I and II IFN production. This leads to the increased formation of mammary carcinomas [34][46]. Mice lacking death-inducing molecule tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) [35][47], or with the inactivation of the Fas-mediated cell death pathway by Fas or FasL mutation, have accelerated hematological malignancies [36][48]. Decreased cytokine production and/or antigen presentation in gene-deficient mice, including Perforin−/− (lack perforin) [37][49], Ifng−/− (lack IFN-γ) [38][50], Perforin−/−Ifng−/− (lack perforin and IFN-γ) [38][50], Perforin−/−B2m−/− (lack perforin and MHC class I expression) [39][51], and Lmp2−/− (defective MHC class I antigen presentation) [40][52], facilitates tumor growth. Due to the decreased IFN-γ secretion, IL-12 and IL-18, two IFN-γ-inducing cytokines, are down-regulated. A previous study found that, compared with wild-type mice, neither IL-12 nor IL-18 deficient mice exhibited increased incidence of tumor development [38][50]. These results suggest that immune effector cells, cytokines, and their related pathways are essential for the regression of tumor development in immunosurveillance. The following findings support the same conclusion. Due to the presence of the constitutively expressing oncogene, Kras, and inhibiting tumor suppressor, p53, tumors growing in immunocompetent mice were retarded compared to those in immunocompromised mice.

2. Immunoediting: How Tumors Hijack Host Immunity and Establish a Favorable Microenvironment

Tumors escape from the immune system via several mechanisms, including the formation of regulatory cells, reduced immune recognition, and production of suppressive cytokines. The immune system fails to restrict tumor development; as a result, tumors evade immune recognition (due to diminished tumor antigens and immunogenicity) and release suppressive cytokines. The regulatory immune cells, Tregs, MDSCs, dysfunctional DCs, and M2 macrophages also express immune regulatory factors, such as IDO and arginase, to construct a tumor microenvironment (TME) that enhances tumor progression and dampens T cell functions. In this escape phase, the balance is toward tumor progression, with the infiltrations of inhibitory cells, cytokines, and factors. The results are that the immune system is incapable of inhibiting tumor progression. By generating the appropriate TME via the mechanisms listed below, tumors dampen the immune responses, supporting tumor growth and even metastasis [41][8].

2.1. Recruitment of Regulatory Cells

2.1.1. Regulatory T Cells

Immune suppression mediated by the regulatory cells and other suppressive factors in the TME is a major mechanism by which tumors avoid attacks from the immune system. CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ tumor-derived regulatory T cells (Tregs) play central roles in immune suppression. Studies also show that different cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β produced by the tumors, trigger the conversion of CD4+ T cells into suppressive Tregs [42][53]. Tregs then secret IL-10, TGF-β, and IL-35 to downregulate antitumor immunity, suppress the antigen presentation by DCs, and decrease the tumor-specific CTLs [43][54]. Meanwhile, since IL-2 is essential to T cell activation and maintenance, these regulatory T cells compete with effector T cells by largely consuming IL-2 [19][20][33,34]. Tregs can also kill the CTLs by the secretion of perforin and granzyme, leading to osmotic lysis and apoptosis, just as CTLs and NK cells do to tumor cells. Furthermore, Tregs interfere with the memory T cells by repressing their effector and proliferation activities through the upregulation of CTLA-4 ligands [44][55]. The aforementioned evidence supports the mediation of the comprehensive suppression of antitumor immunity by Tregs.

2.1.2. Myeloid-Derived Suppressive Cells

Both Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressive cells (MDSCs) facilitate their own expansion by the overexpression of CD73 [45][46][56,57], TGF-β [47][58], and indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO) [48][49][50][59,60,61]. In addition, MDSCs may promote the recruitment of Tregs by producing CCR5 ligands, CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5 [51][62]. MDSCs express a high level of inducible nitric oxide (iNO), which produces nitric oxide (NO) [52][53][63,64]. NO inhibits the JAK/STAT5 pathway and/or suppresses the antigen presentation from DCs, leading to the suppressive proliferation of effector T cells [53][54][64,65]. Furthermore, MDSC-derived NO also triggers the effector T cell apoptosis [55][66] and reduces E-selectin expression on endothelial cells, which hampers the migration of T cells to the tumor sites [56][57][67,68]. MDSCs also secrete a high level of arginase 1 (ARG1), which promotes Treg expansion [58][69] and depletes the L-arginine, a conditionally essential amino acid in effector T cell functions. These actions lead to the dysregulation of effector T cells and the propagation of Tregs [59][70].

2.1.3. Tumor-Associated Macrophages

Among the regulatory cell types, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are the most abundant population in TME [60][71]. There are two polarization states of TAMs: classically activated M1 and alternatively activated M2 subtypes [61][72]. M2 macrophages produce several anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and TGF-β, to inhibit immune systems and promote tumor progression [62][63][64][73,74,75]. Therefore, CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages having an M2 phenotype are considered regulatory (or “bad”) macrophages [65][76], which are essential for tumor growth and metastasis. [66][77]. Furthermore, M2 macrophages can support tumor-related vasculature by accumulating vascular endothelial cells [67][78]. M2 polarization is induced by several factors, one of which is a colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1). CSF1 plays a fundamental role in pro-angiogenesis and tumor burden increase [68][79], revealing M2 macrophages as the efficient cancer development enabler within the TME [66][77]. In fact, M2 participates in the angiogenesis cascade, which consists of a series of pro-tumor functions, including degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM), endothelial cell proliferation, and migration [69][80]. M2-related enzymes promote ECM deposition and the proteolysis of collagens. The degraded collagen fragments may stimulate M2, which could further re-arrange stroma and enhance the angiogenesis activities [70][81]. Therefore, M2 macrophages are immune cells that promote tumors by releasing suppressive cytokines, triggering tumor angiogenesis, and reorganizing the ECM in the TME.

2.2. Defective Antigen Presentation

2.2.1. Manipulation of the DC Lineage

Defective antigen presentation is another fundamental mechanism by which tumors evade immune surveillance. Immunogenic tumors will be recognized and destroyed by immunosurveillance. However, tumors evolve multiple skills for escaping from immune recognition, including the suppression of DC functions and downregulation of MHC-I expression [71][82]. DCs play essential roles in the initiation of antitumor T cell immunity [3][5]. Among the DC subsets, cDC1s (c: conventional) are the most important [72][83], for the abundance of cDC1s in the TME is associated with T cell infiltration and overall survival in cancer patients [4][73][20,84]. cDC1s are recruited to tumor regions by chemokines released by the tumors, such as CCL4 and CCL5 [74][75][85,86]. After taking up tumor cells, cDC1s will mature in the tumor sites and migrate to the dLNs to process tumor antigens onto MHC-I for presentation to CD8+ T cells [4][20]. These processes result in the activation of antigen-specific CTLs. Thus, cDC1s participate in antitumor activities and serve as targets for tumors to escape from the immune system. Tumors prevent the accumulation of cDC1s by activating their β-catenin signaling pathways, thereby decreasing the infiltration of cDC1s and T cells [74][75][85,86]. Furthermore, tumors release high levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [76][87], VEGF [77][78][88,89], IL-6 [79][90], IL-10 [80][91], and TGF-β [81][92] to suppress DC maturation and differentiation. Thus, tumors can decrease their antigenicity by manipulating DC functions, which become tolerogenic and immunosuppressive phenotypes.

2.2.2. Sabotage of the Machinery of Antigen Presentation

The downregulation of tumor antigenicity, such as MHC class I loss, is a well-studied characteristic of immune evasion from tumor-specific cytolytic effects. Tumor antigenicity is sculpted during immunoediting in an immunocompetent host. Some of these changes include antigen depletion [82][93], gene alterations in MHC-I and B2M [83][94], and modulation of other antigen processing and presentation machinery (APM). Several TAAs are the by-products during tumorigenesis, which indicates that these TAAs are not necessarily functional for tumor growth. The loss of such antigens in tumors can prevent immune predation [71][82]. MHC-I and B2M mutations are usually found in tumors [83][94], and they lead to reduced surface expression of MHC-I [84][95]. Diminished B2M expression is correlated to a cold immune environment, with low T cell infiltration [82][93]. Tumors evading immune surveillance by downregulation of APM components are also widely described. Deficiency in proteasome subunits [85][96], transporters associated with antigen processing (TAP) proteins [86][97], and Tapasin [87][98] result in inadequate antigen presentation, thereby escaping CTL recognition. In conclusion, the downregulation of tumor antigens and antigen-presenting processes leads to enhanced tumor growth and metastasis as the CTLs fail to identify the targets on the tumor cells.

2.3. Immune Suppressive Mediators

Tumors can also inhibit host immunity by releasing regulatory cytokines. Within the TME, tumor-induced cytokines and inflammation facilitate cancer development [88][89][99,100]. Several tumor-promoting cytokines are regulated by nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), a central orchestrator of inflammation. Previous research has revealed that the inactivation of NF-κB in immune cells decreases the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and thus relieves the tumor burden [90][101]. These results indicate that NF-κB-mediated cytokines, including IL-1 [91][102], IL-6 [92][103], IL-8 [93][104], and TNF-α [91][102], are highly correlated to tumorigenesis. For example, IL-6 interacts with the receptor JAK and induces STAT-3 activation [92][103], which triggers oncogenes such as myeloid cell leukemia-1 (MCL-1) and upregulates proliferative genes, Cyclin-D1, in tumor cells [94][105]. In addition, TGF-β is one of the most important contributors to tumor growth. TGF-β is released by the cancer cells, Tregs, fibroblasts, and other types of cells within the TME. The elevated TGF-β levels inhibit effector T cell differentiation, promote Treg proliferation, and dampen DC functions [95][106]. Furthermore, TGF-β enhances the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), synergistically triggering tumor metastasis with IL-6 via the overactivation of JAK/STAT signaling pathways [96][107]. Therefore, TGF-β is usually regarded as a chief mediator within the immunosuppressive factors [97][108].

The overproduction of PGE2 [76][87], VEGF [77][78][88,89], IL-6 [79][90], IL-10 [80][91], and TGF-β [81][92] from tumors will inhibit DC differentiation. The undifferentiated DCs fail to appropriately present antigens and are unable to educate T cells. Immunosuppressive enzymes, such as IDO and arginase, also cause tumor progression through the induction of T-cell tolerance and tumor cell proliferation. IDO impairs CTL functions through the downregulation of the T cell receptor ζ chain and enhances Treg generation [98][99][109,110]. Elevated intertumoral IDO expression is correlated to T cell dysfunction, such as decreased levels of granzyme B in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells [100][111], impaired degranulation of γδ T cells [101][112], and upregulation of PD-1 and PD-L1 ligands [102][103][113,114]. Tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells produce high levels of arginase, which inhibit T cell receptor expression, dampen antigen-specific T cell antitumor immunity, and induce Treg proliferation [104][105][115,116].

2.4. Deletion of Tumor-Specific CTLs

Tumors and several immunosuppressive cells trigger T cell apoptosis by Fas and Fas ligand (FasL) signaling pathways. FasL is expressed by tumors and can induce apoptosis of Fas-expressing antitumor CTLs [106][117]. FasL is reported to be expressed on the tumoral endothelium but not normal vasculature [107][118], suggesting that FasL-expressing endothelial cells in tumors induce Fas-mediated apoptosis in CTLs. Furthermore, these phenomena have only been observed in CTLs, not Tregs [108][109][119,120]. FasL-expressing MDSCs also result in the deletion of CTLs [110][111][121,122].

The high expression of CD70 and PD-L1 on the surfaces of tumors also mediates T cell death. The TNF receptor family member CD27 is usually expressed on T cells [112][123], but its ligand, CD70, is overexpressed in some tumors [113][124]. The dysregulation of the CD70–CD27 axis within the TME is associated with immunosuppression [114][125]. One explanation is that the over-activation of CD27 can lead to T-cell deletion, for Siva, a pro-apoptotic protein, can interact with CD27 through a caspase-dependent pathway [115][126]. Therefore, tumors can induce immunosuppression by promoting T-cell apoptosis via the expression of CD70.

PD-L1 and PD-1 induce immune suppression and facilitate tumor growth by induction of T cell apoptosis. PD-L1 is highly expressed in numerous types of cancers, including numerous solid tumors and hematological cancers [116][127]. When tumor-expressing PD-L1 combines with PD-1 on the T cells, SHP-1/2 are recruited to the C-terminal PD-1. This causes the de-phosphorylation of several vital signal transducers, including ZAP70, CD3δ, and PI3K pathways, and thus inhibits T cell proliferation, reduces cytokine production, and triggers T cell apoptosis [116][117][127,128].