Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Juan Sebastián Solis-Chaves.

The MEPS has become a mandatory government document to evaluate the energy efficiency of different equipment and thus limit the minimum energy consumption in domestic, commercial, and industrial applications, guaranteeing end users are able to select more efficient equipment. In order to be compared with the Colombian panorama at the market, technical and political levels, some reference countries and their energy policies were consulted. This allows the establishment of common aspects and differences related to the determination of energy consumption, adjusted volume, and formalization of efficiency ranges, and in the specific case of domestic refrigeration. in Colombia.

- Colombia

- energy efficiency

- energy labeling

- MEPS

1. Introduction

In the last three decades (1992–2022), nations have turned to seeking strategies to mitigate the impacts that have resulted from the intensive use of energy. Solutions and measures that range from the social, political, economic and technological, which seek to regulate and optimize energy resources and minimize the impact of the products derived from them without impairing the quality of life. Measures such as those addressed since the Montreal Protocol in 1987 and the control of gases that deteriorate the ozone layer [1]. Kyoto Protocol in 1997 establishes the measures and strategies to minimize the greenhouse effect [2]. By the agreements derived from COP26 and Paris 2015, which seeks to substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions, in such a way as to control the global temperature rise in this century, with a maximum of 2 °C, or if possible to 1.5 °C. Each signatory country must look for strategies to fulfill the commitments acquired and be reviewed every five years. Likewise, financings are established for developing countries so that they can advance in strategies to mitigate the impact of climate change [3,4][3][4].

As of 2018, 3.6 billion pieces of refrigeration and air conditioning-related equipment were in stock (includes equipment from the residential, commercial, and industrial sectors), of which 45% are domestic refrigerators. In this same year, 350 million pieces of equipment were presented for sale, of which 35% correspond to refrigerators for domestic use [5]. According to the report of the International Energy Agency (IEA), electricity consumption in the residential sector has experienced a progressive growth starting from 3.6 in 1971 to reach 21.9 in 2019 worldwide. In this last year, the electricity consumption corresponding to the residential sector was 26.6% [6]. By 2025, the projection of sales volumes of domestic refrigerators is estimated to reach 236 million units worldwide, which presupposes an increase in energy consumption due to the use of these appliances and highlights the need to demand that they be increasingly efficient [6].

The analysis of energy consumption in homes occupies a place of special interest as a result of the growth that has been taking place due to phenomena such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the promotion of teleworking [7,8][7][8]. Recent studies show the average times of use of household appliances. For the year 2021, energy consumption in the refrigeration area was close to 235 billion kWh in the United States and constitutes 16% of the total electrical consumption at the residential level and 6% of the total electrical energy consumption of the country. The refrigerators have an average daily operation of 15 h and a half being; devices such as television, modem, PC or multimedia devices that handle operating times of 12 h 42 min; illumination with 7 h 58 min; the water heater with 5 h 46 min; among others [9].

In the European Union, refrigerators and freezers represent an energy consumption close to 86 TWh per year, which corresponds to 11% of residential electricity consumption [10]. Due to all of the above, the implementation of energy efficiency standards MEPS, establish minimum performance conditions, to reduce energy consumption in the home, they have become a state policy for both developed and developing countries [11].

The MEPS are applicable to electrical appliances such as lighting fixtures, refrigerators, air conditioners and electric motors, among others, and these are mandatory for manufacturers and marketers [12]. The application of the MEPS, in addition to having commercial purposes, is also aligned with objectives linked to environmental policies and the normalization of energy consumption under particular operating conditions for household appliances and devices in general, with which the governments of some countries are committed to through international agreements, for example, the SDGs [13] and the Energy Charter treaty [14]. The implementation of MEPS has contributed up to 5% of savings between 2018 and 2019 worldwide [13,15][13][15].

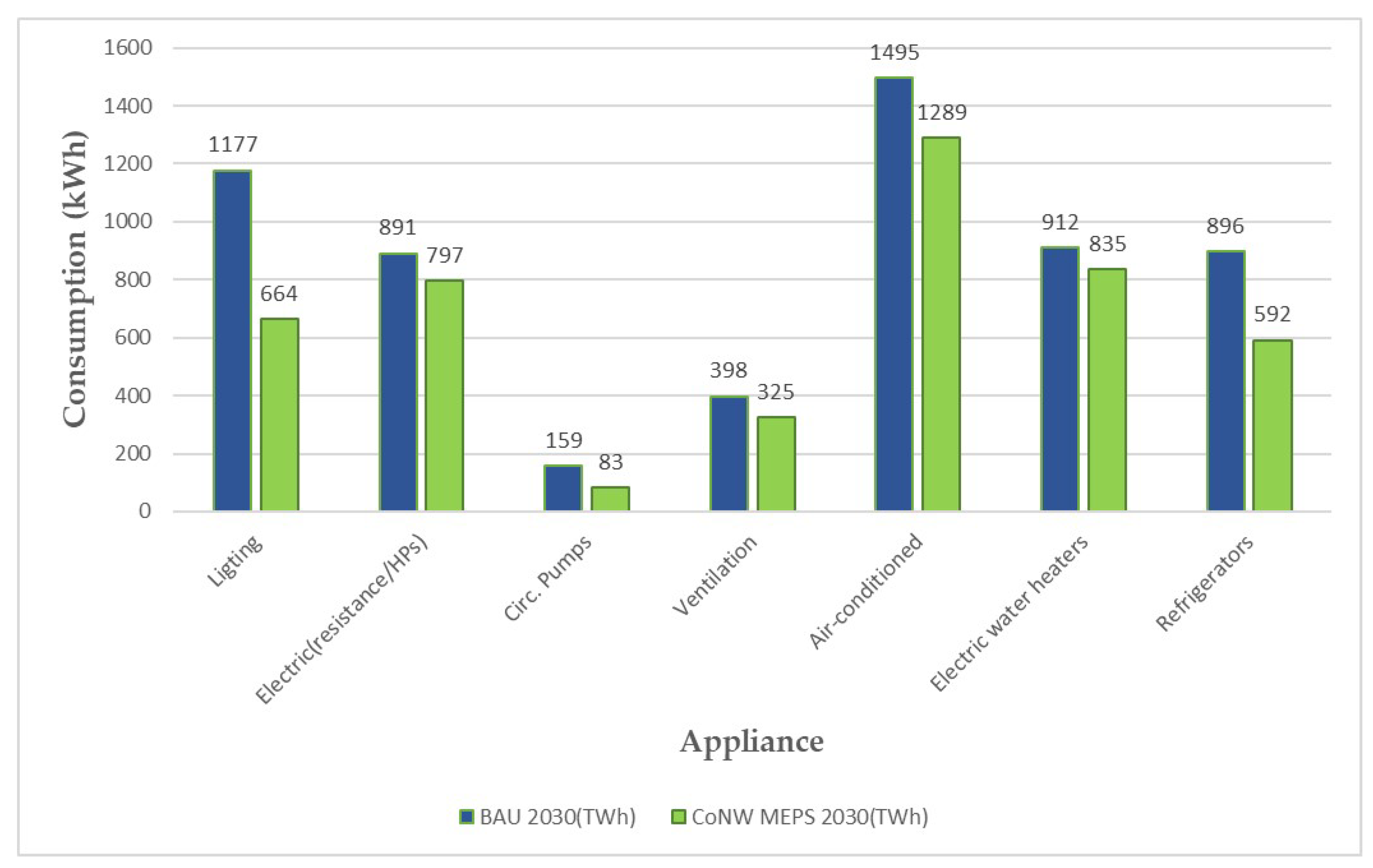

The MEPS promotion policy has evolved in the last two decades, establishing specific requirements to reduce the energy consumption of household appliances [16]. Figure 1 shows the projection in the reduction of consumption in kWh by 2030 by 2030 worldwide of some household appliances for residential use, among which is the refrigerator, where the BAU consumption corresponds to the energy consumption by household appliances with current technologies by 2030 and the CoNW MEPS consumption corresponds to the projected consumption applying the best MEPS technologies and policies [17].

Figure 1. Estimated reduction in refrigeration consumption by applying BAT and MEPS to 2030. Adapted from [17].

The MEPS guide the user to be able to acquire more efficient equipment. In this way, these policies help to reduce the energy demand of the residential sector mainly, leaving obsolete equipment (not very efficient) out of the market [18]. As a strategy for the application of the MEPS, labeling programs emerge in order to inform the consumer about the specific characteristics of electrical appliances. The implementation of these policies, together with those of labeling, have proven to be effective in reducing GHG, responsible for global warming.

Additionally, by reducing the final consumption of electricity, it is possible to reduce the use of capital investment in the energy supply infrastructure, for instance, the construction of power plants and the reduction of raw materials such as hydrocarbons used for the generation of energy in thermoelectric plants, thus reducing long-term environmental impacts [19].

Currently, more than 80 countries have implemented or are in the process of implementing labeling programs based on the goals set by the different nations on issues related to climate change [20]. The ultimate goal of the label on household appliances is to describe the energy yield of a product so that the consumer can make purchasing decisions and, in turn, encourage the rational use of electrical energy through the acquisition of efficient equipment [21].

In addition, it allows the user to control the economic expense reflected in the billing for the use of electrical energy [22].

The labels proposed in the different programs can be of two types, comparison labels, and recommendation labels [23]. The comparison ones provide information to the user about the performance of a specific product and compare it with the performance of other products of the same family that exist in the market, commonly used in countries of the European Union, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, among others. Recommendation ones are also known as guarantee seals, which are generally associated with energetically efficient products, as in the case of Energy Star. The recommendation label «not to buy products» makes known how energy efficient a device is, in addition to being also known as guarantee seals (for example, the Energy Star seal in the United States) [24].

The informative labels are attached to a manufactured product and include energy consumption characteristics such as the monthly or annual consumption of the equipment and its respective category [25]. Energy consumption and its dynamics of change are subject to ongoing analysis in the international and national context due to its multi-factorial impact on social, economic, and environmental aspects.

In the national context, in 2015, the residential sector represented 16.2% of the total final energy consumption in Colombia thanks to this percentage, it was possible to identify that the principal energy consumption is due to refrigeration, television, lighting, and cooking [26]. According to the National ECV carried out in 2021, more than 80% of Colombian households had at least one refrigerator-freezer in use, which represents between 20% and 50% of electricity consumption of Colombian households [27]. Therefore, improving energy efficiency in the residential sector has been one of the objectives of the rational use of energy policy in Colombia, achieving an increase in the efficiency of the different electrical appliances [28].

Currently, Colombia does not have MEPS policies. However, in 2015 it implemented the RETIQ [29], which establishes measures that promote the Rational and Efficient Use of Energy (URE) in products that use electricity and gas through the establishment and mandatory use of labels that report on their performance in equipment associated with cold production, lighting, driving force, and heat production, particularly focused on the residential and commercial sectors.

2. MEPS & Labeling Policies

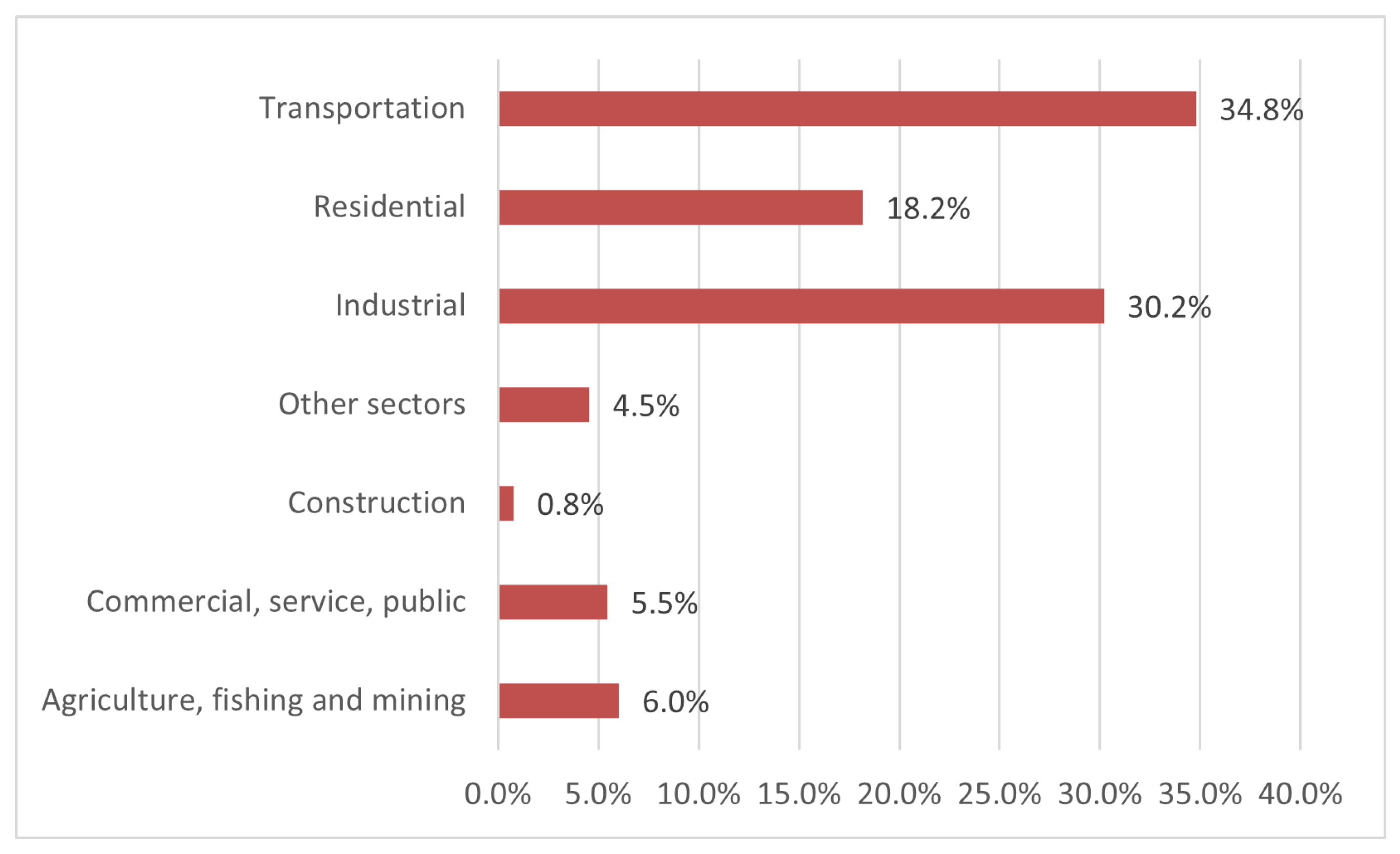

Figure 2 hows consumption by sector in Latin America and the Caribbean for the year 2020, in which the transport sector participates with 34.8% of the total, followed by the industrial sector (30.2%) and the residential sector (18.2%). In addition to other sectors such as commercial and services, agriculture and mining, construction and others, which together cover the remaining 16.8%.

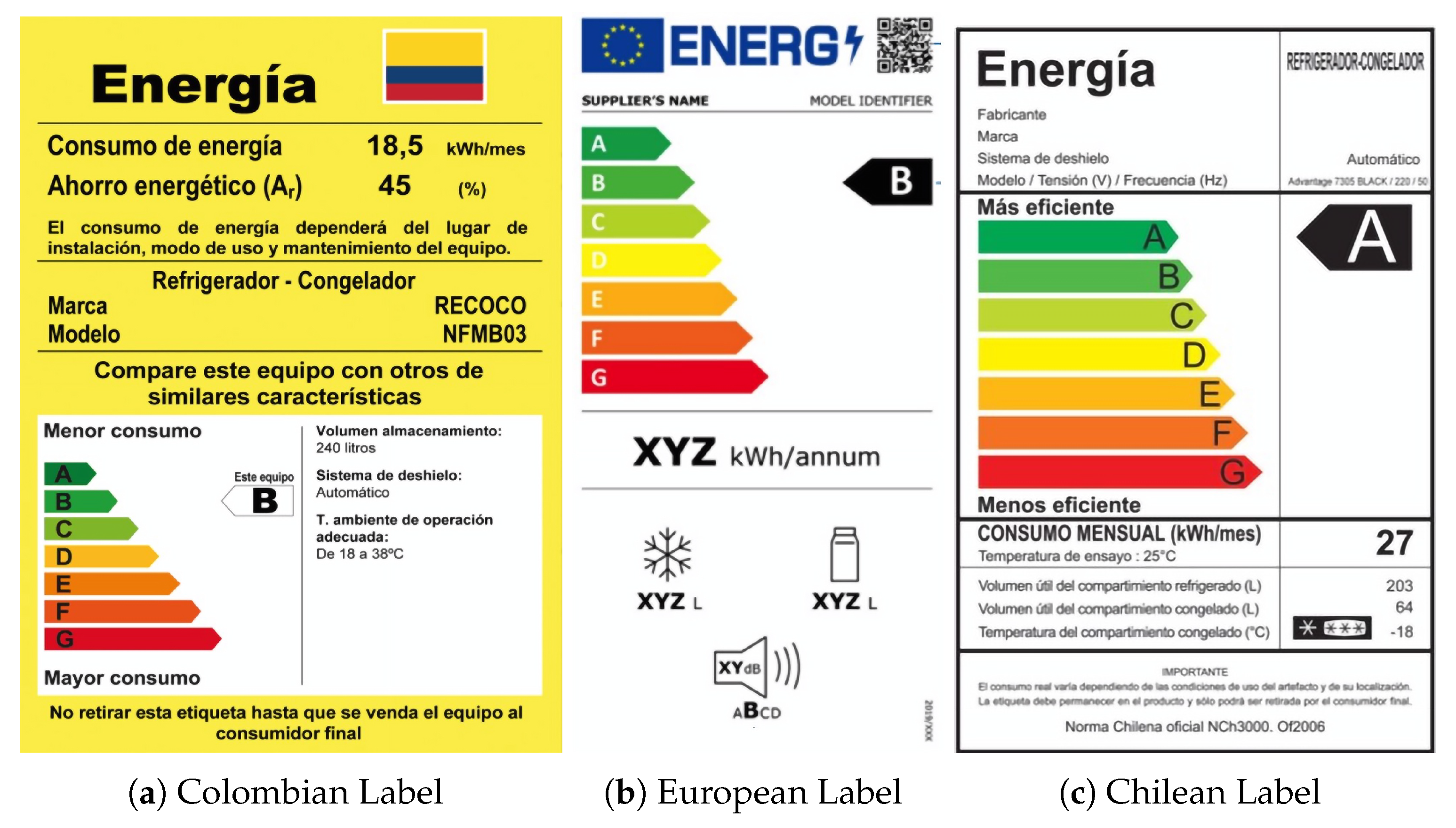

Figure 3. Energy Labels for Domestic Refrigeration in Colombia, EU and Chile.

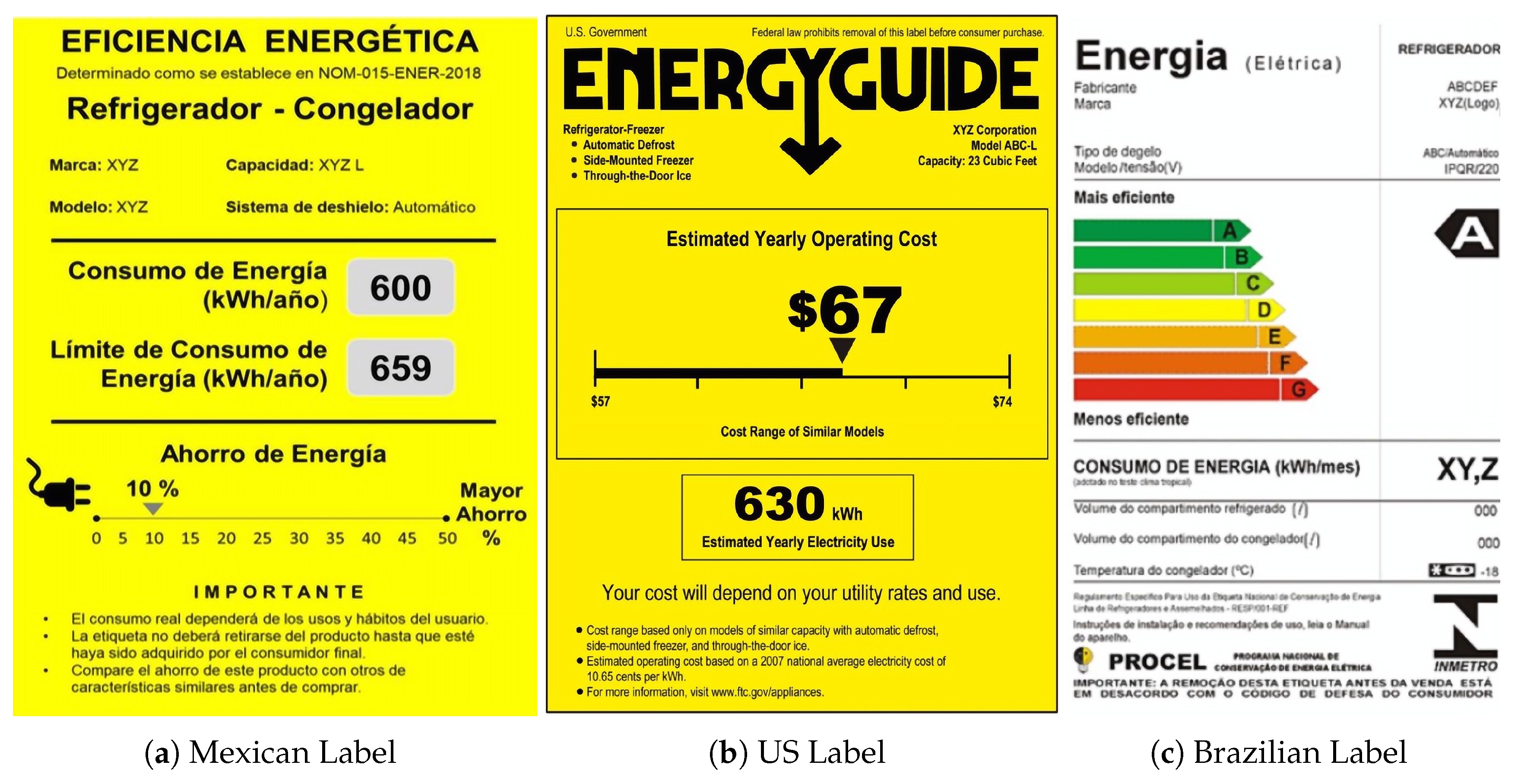

Figure 4. Energy labels for domestic refrigeration in Mexico, US and Brazil.

2.1. European Union

In the European Union, the implementation of the appliance labeling program for the first time was in 1992 with the EU Directive 92/75/EC on the «Indication Through Labeling and Standard Information of the Consumption of Energy and Other Resources by the Appliances» [39][33] establishing an initial classification of categories from A to G, in which category A represents the most efficient equipment and G would be the least efficient category, It is noteworthy that the label does not provide the IEE given by the manufacturer, but rather the category where the IEE is found. Later the European Union would migrate to an update of its labeling policies by changing the categorization of the label categories [40][34]. In the year 2000, new, more efficient equipment emerged, for which the EU Delegated Regulation 1060/2010 was updated, incorporating categories A+, A++ and A+++ [41][35]. In 2016, this Delegated Regulation of 2010 is updated again, eliminating the categories from E to G and adding the noise level categorization on the label [42][36]. this update hardened the distribution of less efficient equipment in the European Union countries. The preliminary review of the MEPS process in Europe shows that the implementation in the different EU countries is not the same, revealing marked differences due to the promotion that governments make about efficient equipment and the subsequent removal of equipment with higher consumption from the market. The reason for these differences is given, according to the criteria of some authors and the heterogeneity in the composition of the stocktaking of electrical appliances between countries that directly influence the effectiveness in the MEPS application and energy labels [10,43][10][37]. From 1 September 2021, categories A +, A++ and A+++ were included again, recategorizing [44][38], which generated confusion in the population. In addition to the MEPS and the labeling regulation, the EU adopted the Climate Change Plan determined by the European Directive 20/20/20 [45][39], the main objective of this Plan is to reduce GHG emissions by 20%, and improve the energy efficiency of buildings by 20% [46][40]. An important indicator on the implementation of MEPS in Europe is an improvement of around 27% in the efficiency of domestic refrigeration appliances, compared to prelabeling efficiency levels. According to EU reports, the average energy consumption of refrigerators fell from approximately 450 kWh/year in the period from 1990 to 1992 to an estimated 364 kWh/year immediately after MEPS was adopted [47][41]. Emissions derived from the use of electrical appliances represented 25% of total emissions in 2010, increasing equally to the emissions produced by the industrial sector [48][42]. The growing increase in the purchase of household appliances leads to the creation of new control policies that help mitigate the effects produced by the use of residential appliances, among which are domestic refrigerators [49][43], for example, the comparative label, which has a high impact on home appliance buyers and provides better decisions in the acquisition of new and more efficient products [50,51,52][44][45][46]. See Figure 3b, in which the current label is shown. The review of energy efficiency policies and MEPS labeling shows a more comprehensive trend on the part of the EU when assessing the energy performance of the equipment, including regulations related to ecodesign, thus seeking to integrate environmental aspects in the design, production, distribution, use and final disposal of the product throughout its life cycle [53,54][47][48]. Among the novelties proposed in the energy label, there is a QR link that expands the information and provides more details about the product, such as its materials and manufacturing processes in general. Additionally, it has been proposed to include standards on repairability and availability of spare parts. Finally, it promotes the use of recycled materials in the manufacture of new models [55][49]. An additional element that stands out in the EU energy label is the inclusion of the noise parameter, which links to the application of compartment design strategies and the control of refrigerant fluids, thus achieving a reduction in noise emissions and an improvement in sound quality in non-Frost type refrigerators, which are the most commercialized [56,57][50][51].The noise regulation extends to other devices such as air conditioners and is undoubtedly an important criterion at the time of purchase, not only due to aspects of comfort during the operation of appliances but also due to the close correlation that exists between the decreased noise and energy efficiency [58,59][52][53].2.2. United States

One of the main barriers to improving the energy efficiency of US household appliances for residential use is the high cost of acquiring new technologies by manufacturers to produce more efficient equipment. One of the strategies to address this barrier is by implementing incentives for both manufacturers and consumers, lowering the production cost and equipment acquisition [60][54]. Mechanisms such as electrical appliance labeling programs (MEPS) have influenced the purchase by users of more efficient refrigerators. Mechanisms such as electrical appliance labeling programs (MEPS) have influenced the purchase by users of more efficient refrigerators. Studies such as the one by Zainudina et al. show that there are close relationships between knowledge, attitude, social norms, and the energy efficiency label of users with the purchase intention [61][55]. In the United States, the first MEPS standards were applied in 1974 for refrigerators at the state level. However, until 1978 through the NECPA, it established the obligation of minimum standards at the national level. Between 1974 and 2004 there was a reduction in energy consumption of 74% associated with the implementation of measures such as MEPS [62][56]. This country implemented the EnergyStar seal in 1992 as a complementary measure to the MEPS, which represented the most significant government effort in the country, and which would represent a saving of 164 million dollars annually in electricity costs in homes, with a reduction in carbon emissions of approximately 1.1 million metric tons per year [63,64][57][58]. In the development of labeling programs comes the Energy Guide label (a comparison label), administered by the FTC. Later, in 2001, the DOE, together with the EPA, were in charge of exercising control over the EnergyStar label [65][59]. At the end of the same year, the NAEWG group was created, with the aim to improve the commercialization, development, and interconnections of North America [66][60]. The participating countries (Mexico, Canada and the United States), created this working group specifically to study and improve the policies, energy efficiency, renewable energy, clean energy and nuclear energy of these countries. For 2020, EnergyStar established updates in terms of trial and test methodologies [67][61], an example of US Energy Label is shown in Figure 4b.2.3. Mexico

Over the last few years, energy consumption in the residential sector in Mexico has had a considerable increase. Studies reveal that the kitchen is the main factor in final energy use and that water heaters and other appliances are the ones that show the higher growth [68][62]. Strategies have been seeking to meet the demand of the different country regions through energy generation from renewable sources and developing new energy efficiency standards that can be applied in government policies to control energy use [69][63]. In 1992, the Mexican Energy Efficiency Standardization System began with the Federal Metrology and Standardization Law, coordinated by the National Consultative Committee for Official Mexican Energy Efficiency Standards (NOM-ENER), which are mandatory [20]. These standards establish the testing procedures, the MEPS, as well as the labeling requirements [34][64]. In 2002, the Nom-015-Ener-2002 standard was proposed, which establishes the parameters for evaluating the energy efficiency of refrigerators and freezers, the limits, test methods, and labeling [70][65]. The energy label used in Mexico, its testing procedures and MEPS are adapted from the United States energy guide model, including a continuous scale that indicates the relative savings of the product concerning the threshold defined by the standard [71][66]. In 2012, the CONUEE enacted the update of the NOM-ENER-2002, updating the maximum limits of energy consumption of refrigerators and freezers for domestic use, operated by a hermetic compressor motor, according to the type of refrigerator and its defrost system [72][67]. As of 2018, 29 standards are current, including specifications for refrigeration appliances, as well as standards that control CO2 emissions and fuel efficiency of automobiles. In addition, the standards and mandatory labeling program of the CONUEE and the Fiduciary FIDE [73][68] offer manufacturers the possibility of acquiring a FIDE endorsement-seal label for equipment that exceeds the minimum level of energy efficiency defined by the NOM [74][69]. A Mexican energy label is presented in Figure 4a. In that same year, the Nom-015-Ener-2018 was published, and the program to replace old and inefficient refrigerators with modern and high-efficiency models was proposed. In this way, Mexico would save 4.7 TWh/year [34,75[64][70][71],76], projecting a decrease in total residential electricity consumption of 9.9%, and the associated expense decreases by 11.3%. Additionally, the electricity subsidy decreases by 7500 million Mexican pesos per year (that is, 403 million dollars at the average exchange rate registered in 2017), and there is an annual decrease of 3.9 million tons of CO2 equivalent emissions [77][72].2.4. Chile

In early 2005, the Chilean government established the Energy Efficiency Standards and Labeling Program (PPEE), to be implemented in 2006. This was one of the most visible and comprehensive energy efficiency programs in the region. In 2007, the energy efficiency labeling came about and with it the first rational energy use program «Use Energy Well—Follow the Current», creating regional energy efficiency tables and diagnosing several productive sectors in the country [78][73]. In 2008, the implementation of energy labeling for refrigerators-freezers was carried out, according to efficiency standards ISO 15502 [79][74], IEC60335-2-24 [80][75], and according to the NCh3000 [81][76]. Subsequently, the Ministry of Energy received technical assistance from the Division of Environmental Energy Technologies of the LBNL and issued in 2012 the regulation that defines the criteria and procedures that will be applied to establish MEPS. The regulation requires, among other things, the preparation of a regulatory impact assessment, consultation procedures and coordination between government entities and the public [82][77]. In 2014, Decree No. 64 was established, which approves the regulations that establish the procedure for the elaboration of technical specifications for energy consumption labels and the necessary standards for their application [83][78]. In the 2016 follow-up report, the Chilean government reaffirms its commitment that 100% of commercialized appliances are energy-efficient equipment, as promoted in one of the goals for the year 2050 [84][79]. For 2018, the total consumption of refrigerants in the domestic refrigeration and air conditioning sector reached 70% of the substance bench-marking in Chile [83][78]. More recent studies show how the Chilean government has proposed campaigns to diagnose the current situation in the refrigeration sector, based on the quantification of equipment. Thus, in 2019 it was estimated that the installed fleet of refrigerators in Chile of around 6.8 million units as part of the Baseline Report for the project entitled «Accelerating the Transition to a Market of Efficient Refrigerators in Chile» which 43% belonged to energy efficiency category B or lower. The predominant EE categories in Chile are category A+ and category A with 28% and 25% participation, respectively. A Chilean domestic refrigerator energy label appears in Figure 3c. Additionally, this report considers the refrigerants used in this equipment, which cause a high environmental impact, so they must be regulated by applying mitigation policies [85][80]. Currently, these standards are mandatory and introduced through protocols and resolutions issued by the Superintendence of Electricity and Fuels (SEC). This one is in charge of adapting to the test conditions related to the labeling apply to products such as motorized vehicles and boilers in the industrial mining sector, among others [86][81].2.5. Brazil

As antecedents of energy expenditure produced in the residential sector, since 1980, the Brazilian government has worked on policies that reduce energy losses and on programs that encourage energy efficiency in end-use equipment [87][82]. In 1993, the National Energy Conservation Program (PROCEL) voluntarily introduces the labeling program, adopting a classification ranging from category A to E, with A being the most efficient category and E the least efficient [87][82]. A decade later, the PEB emerged, incorporating mandatory labels (please see Figure 4c), with as main objective of informing the consumer about specific characteristics of consumption, temperature, and additional information, such as: brand, model, defrost type, refrigerator size (usually in liters), freezer size and temperature, to end users. It is noteworthy that the form of the labels implemented in Brazil based on the US model, adapting the Energy Guide label [88][83]. Brazil is considered one of the pioneering countries in programs related to climate change, which acquired the commitment to reduce its carbon footprint between 36% and 39% by 2020. This carbon footprint receives a considerable contribution from part of the residential sector. In 2013, household energy consumption represented around 9% of total energy consumption in Brazil and accounted for about 994 PJ due to an increase in energy consumption in this sector since 2005 [89][84]. Due to the significant energy consumption by refrigerators for residential use in 2007 corresponding MEPS were established, taking as a starting point the «Energy Efficiency Law» enacted in 2001 [90][85]. This year they were achieved energy savings of approximately 1379 GWh and a reduction of 197 MW in Brazilian demand, as a result of efficiency labeling in refrigerators and freezers [91][86]. As a consequence of the labeling and MEPS policies introduced in Brazil in 2009, complementary policies to labeling emerge, such as the national refrigerator exchange program, which encourages the replacement of inefficient refrigerators [92][87]. The annual energy consumption of domestic refrigerators in 2010 was 182.8 GWh, and according to the projections made, the future impacts of the Energy Efficiency Law. It is estimated that the energy savings for the year 2030 would be close to 14,325 GWh, which represents 9% of the installed capacity for the electricity generation in 2010 [87][82]. According to the Energy Efficiency Indicators Management Committee (CGIEE), these standards must be undergoing a review process every two years, being updated for the last time in 2011 [93][88]. Since 2013, Brazil has had an electrical energy conservation program (PROCEL), distinguishing the most efficient products in the market, industry, buildings, government and public lighting. This seal was successfully applied to more than 36 appliances from more than 150 manufacturers [62][56]. Since the enactment of Law 13 280/2016, PROCEL has been able to count on energy providers to dedicate 20% of their resources to energy efficiency through the PROCEL resource application plan [94][89]. By 2018, 7.3% of final energy use was covered by mandatory energy efficiency policies [95][90]. With the implementation of PROCEL actions, it was possible to save a total of 23 TWh, which in Brazil’s energy consumption was equivalent to 4.87% of consumption for 2018 [94][89].2.6. Colombia

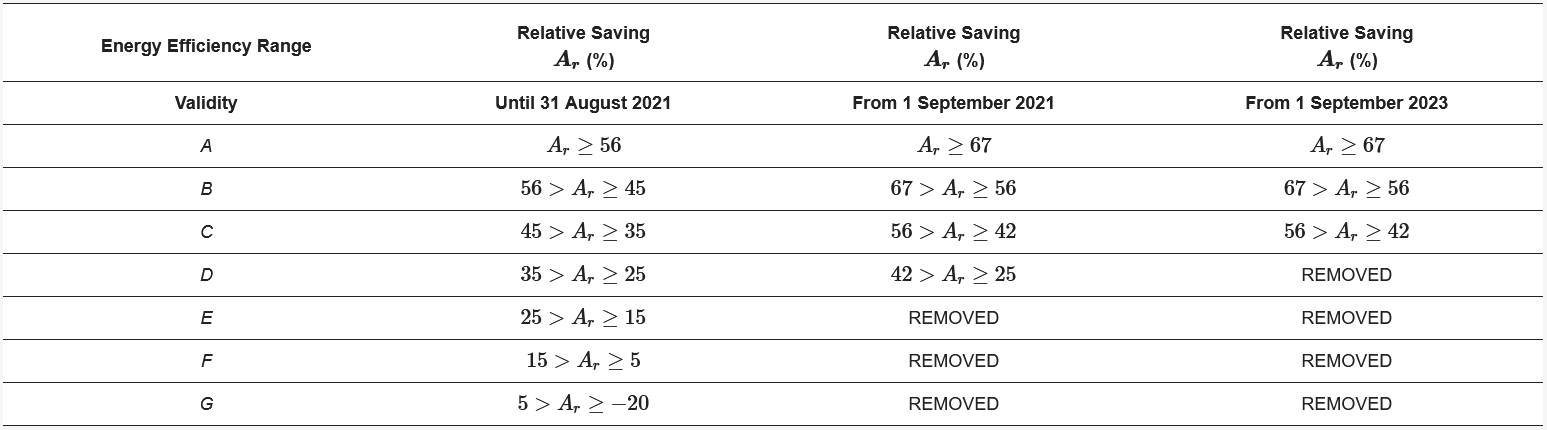

In Colombia, the residential sector represented 40% of electricity consumption in 2015, of this percentage refrigerators represent 43.25% [28,32][28][91]. In 2015, the RETIQ was launched, establishing the energy label (as is shown in Figure 3a) for household appliances for residential use and an information label for equipment for commercial use [29]. Seven energy efficiency categories are stipulated, from A to G, with A being the most efficient and G the least efficient. As of 1 September 2021, the last three categories will disappear and along with them, the domestic refrigerators thus categorized. In Table 1, you can see the ranges of energy efficiency and the relative savings levels with which household refrigeration equipment is categorized for the year 2021 and the perspective towards the year 2023, where category D is expected to be eliminated.Table 1. Energy efficiency ranges for domestic refrigeration equipment for Colombia from 2021 to 2023.

References

- Secretaria del Ozono. Manual del Protocolo de Montreal relativo a las Sustancias que Agotan la Capa de Ozono; Secretaria del Ozono: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016.

- Naciones Unidas. Protocolo de Kyoto de la Convención Marco de las Naciones Unidas Sobre el Cambio Climático; Technical Report; Naciones Unidas: Santiago, Chile, 1998.

- Naciones Unidas. Convención Marco sobre el Cambio Climático; Naciones Unidas: Santiago, Chile, 2015.

- Schloss, M. COP 26: ¿Hacia dónde se va? In Proceedings of the Conferencia de la Nacionaes Unidas Sobre el Cambio Climático cop26, Glasgow, UK, 31 October–13 November 2021.

- University of Birmingham. A Cool World Defining the Energy Conundrum of Cooling for All; Technical Report; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2018.

- Statista.com. Global: Refrigerator Sales 2012–2025; Statista.com: New York, NY, USA, 2021.

- Unidad de planeación minero energtica (UPME). Proyección Demanda Energéticos ante el COVID-19; UPME: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020.

- Cheshmehzangi, A. COVID-19 and household energy implications: What are the main impacts on energy use? Heliyon 2020, 6, e05202.

- Rosin, A.; Auvaart, A.; Lebedev, D. Analysis of Operation Times and Electrical Storage Dimensioning for Energy Consumption Shifting and Balancing in Residential Areas. Electron. Electr. Eng. 2012, 120, 15–20.

- Schleich, J.; Durand, A.; Brugger, H. How effective are EU minimum energy performance standards and energy labels for cold appliances? Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112069.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Efficiency 2020; IEA: Paris, France, 2020; p. 105.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Achievements of Energy Efficiency Appliance and Equipment Standards and Labelling Programmes; IEA: Paris, France, 2021.

- Naciones Unidas. La Agenda 2030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible una Oportunidad para América Latina y el Caribe; Technical Report; Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean: Santiago, Chile, 2018.

- Carta internacional de la energia. In Proceedings of the Conferencia Ministerial sobre la Carta Internacional de la Energía, The Hague, The Netherlands, 20 May 2015; 2015; p. 44.

- Zhang, R.; Fu, Y. Technological progress effects on energy efficiency from the perspective of technological innovation and technology introduction: An empirical study of Guangdong, China. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 425–437.

- Rahman, K.; Leman, A.; Mansor, L.; Salleh, M.; Yusof, M.; Mahathir, M. Energy Efficiency: The Implementation of Minimum Energy Performance Standard (MEPS) Application on Home Appliances for Residential. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Green Design and Manufacture 2016 (IConGDM 2016), Phuket, Thailand, 1–2 May 2016; Volume 78.

- Molenbroek, E.; Smith, M.; Surmeli, N.; Schimschar, S.; Waide, P.; Tait, J.; Mcallister, C. European Commission Savings and Benefits of Global Regulations for Energy Efficient Products; Technical Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Chawla, H. Approach to make smart grid a reality. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Advances in Energy Conversion Technologies—Intelligent Energy Management: Technologies and Challenges, ICAECT 2014, Manipal, India, 23–25 January 2014; pp. 77–82.

- McNeil, M.; della Cava, M.; Blanco, J.; Quiros, K.; Lutz, W.F. Introducción a la Normalización y Etiquetado de Eficiencia Energética en Centroamérica; Diseño Editorial SA: San Jose, Costa Rica, 2008; p. 36.

- Lutz, W.F. Energy Efficiency Standards and Labelling in Latin AMERICA—The Issue of Alignment and Harmonisation; EEDAL: Lucerne, Switzerland, 2015.

- Sasaki, H.; Sakata, I.; Wangjiraniran, W.; Phrakonkham, S. Appliance diffusion model for energy efficiency standards and labeling evaluation in the capital of lao PDR. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2015, 3, 269–281.

- Mcmahon, J.E. Lawrence Berkeley National Energy-Efficiency Labels and Standards: A Guidebook for Appliances, Equipment, and Lighting, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (LBNL): Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005.

- Ministerio de Industria Turismo y Comercio de España. Etiquetado Energético de los Electrodomésticos. Situación del Sector y Planes de Renovación de Electrodomésticos (2006–2007); Ministerio de Industria Turismo y Comercio de España: Madrid, Spain, 2007.

- Ministerio de Energias de Bolivia; Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale. Estudio: Etiquetado Energético para Artefactos Electrodomésticos. September 2019. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=webampersandtag|cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiXlLynq_j5AhVZZd4KHUgVB3MQFnoECA0QAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fenergypedia.info%2Fimages%2Fa%2Fa7%2F19-09-19-ETIQUETADO_ELECTRODOMESTICOS.pdf&usg=AOvVaw218gukcV_OivvGgFoqdx6R (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Romero, J. Regulación de la eficiencia energética: El caso del etiquetado. Rev. Derecho Adm. Económico 2005, 73, 73–94.

- Unidad de Planeación Minero Energética (UPME). Plan de Acción Indicativo de Eficiencia Energética 2017–2022. Available online: https://www1.upme.gov.co/Paginas/Plan-de-Acci,%C3%B3n-Indicativo-de-Eficiencia-Energ%C3%A9tica-PAI-PROURE-2017—2022.aspx (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadisiticas (DANE). Comunicado de Prensa, Encuenta Nacional de Calidad de Vidad 2021; Technical Report; Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadisiticas: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021.

- Ríos, J.; Olaya, Y. A dynamic analysis of strategies for increasing energy efficiency of refrigerators in Colombia. Energy Effic. 2018, 11, 733–754.

- Ministerio de Minas y Energia. Reglamento Técnico de Etiquetado; RETIQ: Bogotá, Colombia, 2015.

- Organización lationamericana de energia (OLADE). Situación del Consumo energético a Nivel Mundial y para América Latina y el Caribe (ALC) y sus Perspectivas; OLADE: Quito, Ecuador, 2020.

- Ren, H.; Tibbs, M.; McLauchlan, C.; Ma, Z.; Harrington, L. Refrigerator cost trap for low-income households: Developments in measurement and verification of appliance replacements. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021, 60, 1–14.

- Bolaji, B.O. Exergetic performance of a domestic refrigerator using R12 and its alternative refrigerants. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2010, 5, 435–446.

- Goeschl, T. Cold Case: The forensic economics of energy efficiency labels for domestic refrigeration appliances. Energy Econ. 2019, 84, 104468.

- Ing Liang, W.; Krüger, E. Comparing energy efficiency labelling systems in the EU and Brazil: Implications, challenges, barriers and opportunities. Energy Policy 2017, 109, 310–323.

- Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea. Reglamento Delegado (UE) N o 1060/2010 de la Comision de 28 de Septiembre de 2010 por; Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- Parlamento Europeo. Reglamento Delegado (UE) 2017/1926 de la Comision de 31 de Mayo de 2017; Parlamento Europeo: Strasbourg, France, 2017.

- Michel, A.; Attali, S.; Bush, E. Energy Efficiency of White Goods in Europe: Monitoring the Market with Sales Data; Technical Report June; Association for the Development of Monfragüe and Its Environment: Hamburg, Germarny, 2015.

- Schubert, T.; Breitschopf, B.; Plötz, P. Energy efficiency and the direct and indirect effects of energy audits and implementation support programmes in Germany. Energy Policy 2021, 157, 112486.

- Parlamento Europeo y Consejo Europeo. Directiva 2018/2002/UE Por la que se Modifica la Directiva 2012/27/UE Relativa a la Eficiencia Energética; Parlamento Europeo y Consejo Europeo: Strasbourg, France, 2018.

- Faure, C.; Guetlein, M.; Schleich, J. Effects of rescaling the EU energy label on household preferences for top-rated appliances. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112439.

- European Commission. Reducing the Price of Development: The Global Potential of Efficiency Standards in the Residential Electricity Sector; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2006; p. 464.

- Kelly, G. Sustainability at home: Policy measures for energy-efficient appliances. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 6851–6860.

- Bertoldi, P.; Mosconi, R. The Impact of Energy Efficiency Policies on Energy Consumption in the EU Member States: A New Approach Based on Energy Policy Indicators; Technical Report; Publications Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- Bertoldi, P.; Mosconi, R. Do energy efficiency policies save energy? A new approach based on energy policy indicators (in the EU Member States). Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111320.

- Harrington, L.; Aye, L.; Fuller, B. Energy impacts of defrosting in household refrigerators: Lessons from field and laboratory measurements. Int. J. Refrig. 2018, 86, 480–494.

- Stadelmann, M.; Schubert, R. How Do Different Designs of Energy Labels Influence Purchases of Household Appliances? A Field Study in Switzerland. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 144, 112–123.

- The Ecodesign Directive for Energy-Related Products. Available online: https://www.eceee.org/ecodesign/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Foelster, A.; Andrew, S.; Kroeger, L.; Bohr, P.; Dettmer, T.; Boehme, S.; Herrmann, C. Electronics recycling as an energy efficiency measure—A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) study on refrigerator recycling in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 30–42.

- European Commission. Simpler EU Energy Labels for Lighting Products Applicable from 1 September; Technical Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Marques, A.; Gomez-Agustina, L.; Dance, S.; Hammond, E.; Wood, I. Noise reduction in commercial refrigerators—A practical approach. In Proceedings of the 20th International Congress on Sound and Vibration 2013, ICSV 2013, Bangkok, Thailand, 7–11 July 2013; Volume 1, pp. 753–760.

- He, Z.; Li, D.; Han, Y.; Zhou, M.; Xing, Z.; Wang, X. Noise control of a twin-screw refrigeration compressor. Int. J. Refrig. 2021, 124, 30–42.

- Héroux, M.; Babisch, W.; Belojevic, G.; Brink, M.; Janssen, S.; Lercher, P.; Paviotti, M.; Pershagen, G.; Waye, K.; Preis, A.; et al. Who environmental noise guidelines for the European Region. In Proceedings of the Euronoise 2015, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 31 May–3 June 2015; pp. 2589–2593.

- Licitra, G. Differences between the principles of the European national noise laws and those of the environmental noise directive. In Proceedings of the Euronoise 2015, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 31 May–3 June 2015; pp. 1045–1048.

- Bansal, P.; Vineyard, E.; Abdelaziz, O. Advances in household appliances- A review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 3748–3760.

- Zainudin, N.; Siwar, C.; Choy, E.; Chamhuri, N. Evaluating the Role of Energy Efficiency Label on Consumers’ Purchasing Behaviour. APCBEE Procedia 2014, 10, 326–330.

- Vieira de Carvalho, A.; Rojas, L.; Mendez, P.; Flam, S.; Couture-Roy, M.; Langlois, P.; Dufresne, V. Guía E: Programas de Normalización y Etiquetado de Eficiencia energética; Inter-America Developement: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; p. 64.

- Boyd, G.; Dutrow, E.; Tunnessen, W. The evolution of the Energy Star® energy performance indicator for benchmarking industrial plant manufacturing energy use. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 709–715.

- Murray, A.; Mills, B. Read the label! Energy Star appliance label awareness and uptake among U.S. consumers. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 1103–1110.

- Hirayama, S.; Nakagami, H.; Murakoshi, C.; Nakamura, M. International Comparison of Energy Efficiency Standard and Labels: Development Process and Implementation Phase; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 110–122.

- Wiel, S.; Van, L.; Lloyd, H. Energy Efficiency Standards and Labels in North America: Opportunities for Harmonization; Technical Report; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA; Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0gj43170 (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Karkova, M. Energy Star. Available online: https://www.ecolabelindex.com/ecolabel/energy-star-usa (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Morillon, G.; Rosas, A.; Floresa, D. What goes up: Recent trends in Mexican residential energy use. Energy 2010, 35, 2596–2602.

- Bansal, P.K. Developing new test procedures for domestic refrigerators: Harmonisation issues and future R&D needs—A review. Int. J. Refrig. 2003, 26, 735–748.

- Jara, N. Impacto de las Políticas Energéticas en la Industria de la Fabricación de Refrigeradores Domésticos en Latinoamérica: Caso México, Colombia y Ecuador. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Medellín, Colombia, 2018.

- Comisión Nacional para el Uso Eficiente de la Energia. Nom-015-ener-2002; Comisión Nacional para el Uso Eficiente de la Energia: Mexico City, Mexico, 2003.

- Lutz, W.F. Eficiencia Energética y Desarrollo Sustentable en Europa y América Latina. In Proceedings of the Foro Nacional “Promoviendo la Eficiencia Energética”, Caracas, Venezuela, 4 October 2002; Available online: https://energy-strategies.nl/files-all/eficiencia-energetica-y-desarrollo-sustentable-en-europa-y-america-latina/ (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Comisión Nacional para el Uso Eficiente de la Energía. NOM-015-ENER-2012; Comisión Nacional para el Uso Eficiente de la Energía: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012.

- Fideicomiso para el Ahorro de Energia Electrica (FIDE). Retos, Logros y Desafios 2013–2018; Technical Report; Fideicomiso para el Ahorro de Energia Electrica: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018.

- Secretaría de Energía (SENER). Fondo para la Transición Energética y el Aprovechamiento Sustentable de la Enegía (FOTEASE); Technical Report; Secretaría de Energía: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018.

- Comisión Nacional para el Uso Eficiente de la Energía. NOM-015-ENER-2018; Comisión Nacional para el Uso Eficiente de la Energía: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018.

- Arroyo, G.; Aguillon, J.; Ambriz, J.; Canizal, G. Electric energy saving potential by substitution of domestic refrigerators in Mexico. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 4737–4742.

- Hancevic, P.; Lopez, J. Energy efficiency programs in the context of increasing block tariffs: The case of residential electricity in Mexico. Energy Policy 2019, 131, 320–331.

- Onofri Salinas, A.M. Análisis del Impacto en el Consumo Eléctrico de la Implementación en Chile de la Política Pública de Estándares Mínimos de Eficiencia Energética para Lámparas Incandescentes; Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2020.

- ISO 15502; Household refrigerating appliances - Characteristics and test methods. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- IEC 60335-2-24; Household and similar electrical appliances—Safety—Part 2-24: Particular requirements for refrigerating appliances, ice-cream appliances and ice makers. Standardization International for Organization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Letschert, V.E.; Mcneil, M.A.; Pavon, M.; Lutz, W.F. Design of Standards and Labeling programs in Chile: Techno-Economic Analysis for Refrigerators. In Proceedings of the 4th ELAEE Montevideo, Montevideo, Uruguay, 8–9 April 2013; p. 18.

- Organización Latinoamericana de Energía (OLADE). Eficiencia energética en América Latina y el Caribe: Avances y oportunidades; OLADE: Quito, Ecuador, 2017.

- Kigali Cooling Performance Program. National Cooling Plan Proposal-Chile; Technical Report; National Cooling Plan Proposal (NCPP): Kigali, Ruanda, 2020.

- Ministerio de Energía Gobierno de Chile. Energia 2050. Política Energética de Chile. Informe de Seguimiento 2016; Technical Report; Ministerio de Energía Gobierno de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2016.

- Volker, K.; Hirsch, M.; Delgado, F. Analisis de la Gestion Ambientalmente Responsable de Refrigeradores y Congeladores de uso Domestico en Chile; Technical Report; Fundacion de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2021.

- Programa de Estudios e Investigaciones en Energia. Estudio de Bases para la Elaboración de un Plan Nacional de Acción de Eficiencia Energética 2010–2020; Technical Report; Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2010.

- Nogueira, L.; Cardoso, R.B.; Cavalcanti, C.; Leonelli, P. Evaluation of the energy impacts of the Energy Efficiency Law in Brazil. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2015, 24, 58–69.

- Huse, C.; Lucinda, C.; Cardoso, A. Consumer response to energy label policies: Evidence from the Brazilian energy label program. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111207.

- Sanches, A.; Tudeschini, L.; Coelho, S. Evolution of the Brazilian residential carbon footprint based on direct energy consumption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 184–201.

- Conrado, A.; de Martino Jannuzzi, G. Energy efficiency standards for refrigerators in Brazil: A methodology for impact evaluation. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 6545–6550.

- Ministério da Economia/Instituto Nacional de Metrologia. Q.e.T. Portaria Nº 332, de 2 de Agosto de 2021. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-n-332-de-2-de-agosto-de-2021-336061973 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Cardoso, R.; Nogueira, L.; Haddad, J. Economic feasibility for acquisition of efficient refrigerators in Brazil. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 28–37.

- Gonzalez, R.; Lucena, A.; Garaffa, R.; Mir, A.R.; Chavez, M.; Cruz, T.; Bezerra, P.; Rathmann, R. Greenhouse gas mitigation potential and abatement costs in the Brazilian residential sector. Energy Build. 2019, 184, 19–33.

- Agencia Internacional de Energia; Ministerio de Minas y Energia de Brasil. Atlas of Energy Efficiency Brazil 2019; Technical Report; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2019.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). E4 Country Profile: Energy Efficiency in Brazil; International Enerrgy Agency: Paris, France, 2021.

- Unidad de Planeación Minero Energética (UPME). Plan Energetico Nacional Colombia: Ideario Energético 2050. Available online: https://www1.upme.gov.co/Paginas/Plan-Energetico-Nacional-Ideario-2050.aspx (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Minestiro de Minas y Energia. Decreto 2143 de 2017; Technical Report; Departamento Administrativo de la Función Pública: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017.

- Unidad de planeación minero energética (UPME ). Comunicado de Prensa no. 009-2018; Technical Report; Unidad de planeación minero energética (UPME): Bogotá, Colombia, 2018.

- IEC 62552-1; Household Refrigerating Appliances—Characteristics and Test Methods—Part 1: General Requirements. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- IEC 62552-2; Household Refrigerating Appliances—Characteristics and Test Methods—Part 2: Performance Requirements. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- IEC 62552-3; Household Refrigerating Appliances—Characteristics and Test Methods—Part 3: Energy Consumption and Volume. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

More