3. Molecular Mechanisms of Liver Regeneration

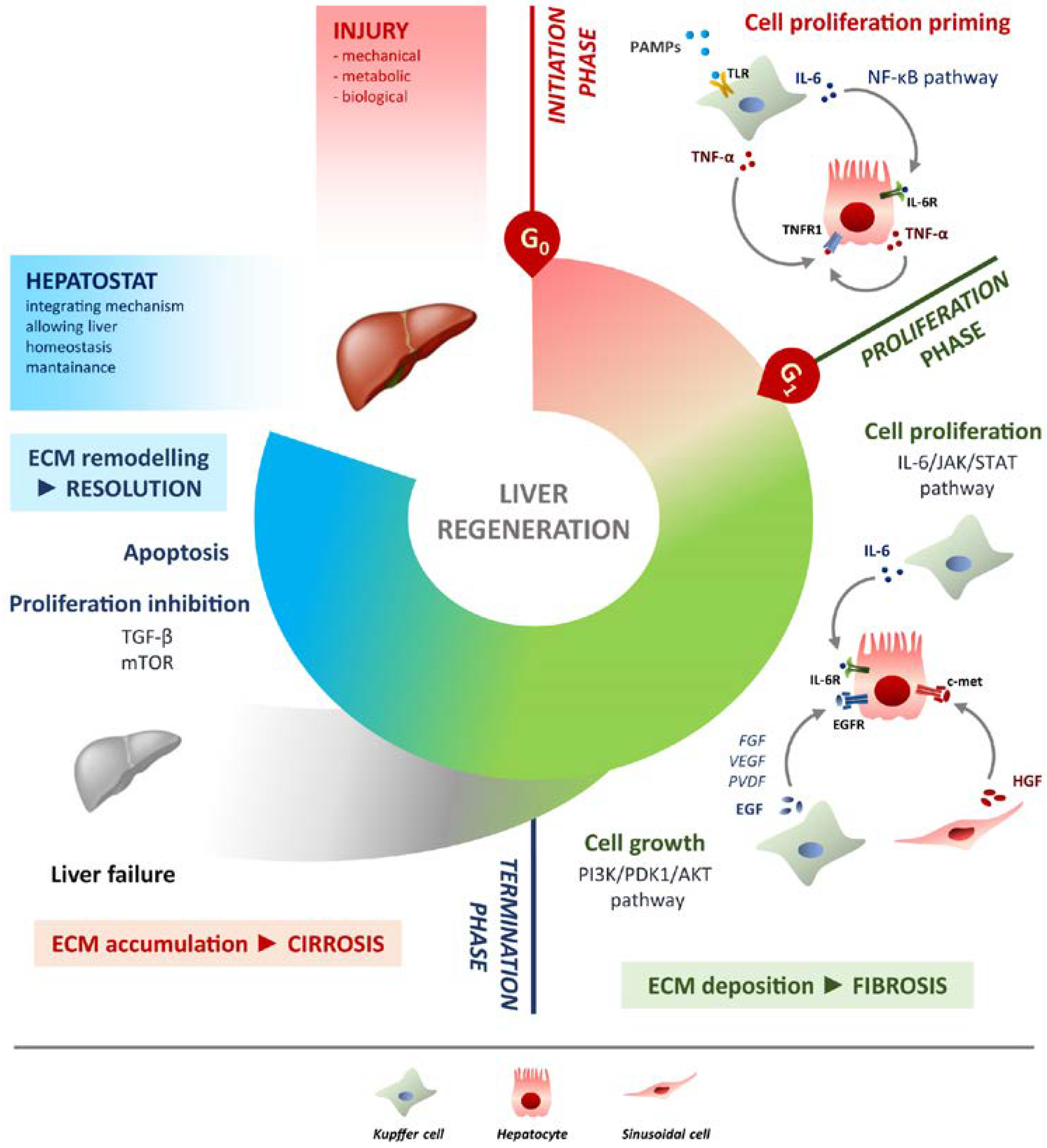

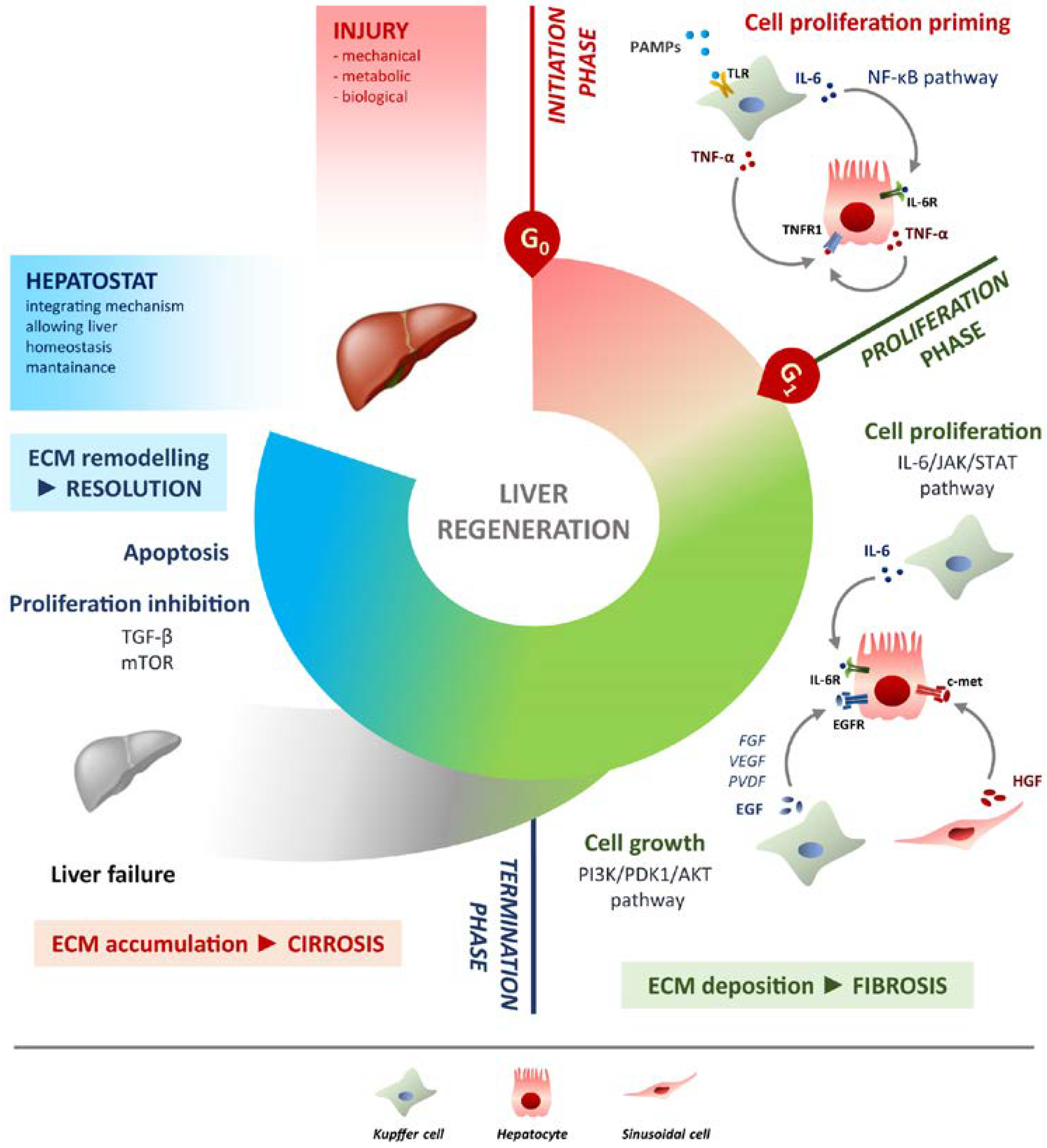

Liver regeneration is the product of tight networking between multiple pathways, but surely the two processes that must be modulated involve cell proliferation and cell growth. They can be defined as two sides of the same coin. Specifically, the interleukin 6 (IL-6)/JAK/STAT-3 pathway is involved in proliferation, while PI3K/PDK1/AKT is responsible for cell growth (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic overview of liver regeneration. LR (liver regeneration) outlined in three phases: initiation, proliferation and termination. In the initiation phase different PAMPs trigger regenerative process by interacting with TLRs exposed on Kupffer cells membrane. Tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6 produced by Kupffer cells activates the NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) pathway in hepatocytes making them responsive to the proliferative signalling and forthcoming to G0/G1 transition. Once IL-6 determined the activation of proliferation, acting on JAK/STAT3 pathway, hepatocytes enter the G1 phase and growth factors signalling ensures their progression in the cell cycle. Kupffer cells and sinusoidal cells sustain hepatocytes growth by producing respectively HGF acting through c-met receptor and EGF. EGFR ligands other than EGF (FGF, VEGF, PDGF and others) act as signal modulators. Growth factors binding to their specific receptors lead to cell growth mainly through the PI3K/PDK1/AKT pathway. The termination phase takes place when the original weight of the liver is reached and results from inhibition of proliferation and growth, and apoptosis induction. The mTOR pathway controls protein translation and together with TGF-β (transforming growth factor-beta) induces hepatocyte expansion inhibition. Apoptosis cooperates with other inhibitory signals, allowing the correct attainment of liver mass. The hepatostat is responsible for the perfect integration of such processes leading liver structural and functional recovery. ECM deposition is a transitory and reversible condition of the regenerative response that arises during the proliferative phase and leads to fibrosis. ECM accumulation requires its rapid and continuous degradation and remodelling to ensure resolution, avoiding cirrhosis outcome and/or liver failure. Schematic overview of liver regeneration. LR outlined in three phases: initiation, proliferation and termination. In the initiation phase different PAMPs trigger regenerative process by interacting with TLRs exposed on Kupffer cells membrane. TNF-α and IL-6 produced by Kupffer cells activates the NF-κB pathway in hepatocytes making them responsive to the proliferative signalling and forthcoming to G0/G1 transition. Once IL-6 determined the activation of proliferation, acting on JAK/STAT3 pathway, hepatocytes enter the G1 phase and growth factors signalling ensures their progression in the cell cycle. Kupffer cells and sinusoidal cells sustain hepatocytes growth by producing respectively HGF acting through c-met receptor and EGF. EGFR ligands other than EGF (FGF, VEGF, PDGF and others) act as signal modulators. Growth factors binding to their specific receptors lead to cell growth mainly through the PI3K/PDK1/AKT pathway. The termination phase takes place when the original weight of the liver is reached and results from inhibition of proliferation and growth, and apoptosis induction. The mTOR pathway controls protein translation and together with TGF-β induces hepatocyte expansion inhibition. Apoptosis cooperates with other inhibitory signals, allowing the correct attainment of liver mass. The hepatostat is responsible for the perfect integration of such processes leading liver structural and functional recovery. ECM deposition is a transitory and reversible condition of the regenerative response that arises during the proliferative phase and leads to fibrosis. ECM accumulation requires its rapid and continuous degradation and remodelling to ensure resolution, avoiding cirrhosis outcome and/or liver failure.

Figure 1. Schematic overview of liver regeneration. LR (liver regeneration) outlined in three phases: initiation, proliferation and termination. In the initiation phase different PAMPs trigger regenerative process by interacting with TLRs exposed on Kupffer cells membrane. Tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6 produced by Kupffer cells activates the NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) pathway in hepatocytes making them responsive to the proliferative signalling and forthcoming to G0/G1 transition. Once IL-6 determined the activation of proliferation, acting on JAK/STAT3 pathway, hepatocytes enter the G1 phase and growth factors signalling ensures their progression in the cell cycle. Kupffer cells and sinusoidal cells sustain hepatocytes growth by producing respectively HGF acting through c-met receptor and EGF. EGFR ligands other than EGF (FGF, VEGF, PDGF and others) act as signal modulators. Growth factors binding to their specific receptors lead to cell growth mainly through the PI3K/PDK1/AKT pathway. The termination phase takes place when the original weight of the liver is reached and results from inhibition of proliferation and growth, and apoptosis induction. The mTOR pathway controls protein translation and together with TGF-β (transforming growth factor-beta) induces hepatocyte expansion inhibition. Apoptosis cooperates with other inhibitory signals, allowing the correct attainment of liver mass. The hepatostat is responsible for the perfect integration of such processes leading liver structural and functional recovery. ECM deposition is a transitory and reversible condition of the regenerative response that arises during the proliferative phase and leads to fibrosis. ECM accumulation requires its rapid and continuous degradation and remodelling to ensure resolution, avoiding cirrhosis outcome and/or liver failure. Schematic overview of liver regeneration. LR outlined in three phases: initiation, proliferation and termination. In the initiation phase different PAMPs trigger regenerative process by interacting with TLRs exposed on Kupffer cells membrane. TNF-α and IL-6 produced by Kupffer cells activates the NF-κB pathway in hepatocytes making them responsive to the proliferative signalling and forthcoming to G0/G1 transition. Once IL-6 determined the activation of proliferation, acting on JAK/STAT3 pathway, hepatocytes enter the G1 phase and growth factors signalling ensures their progression in the cell cycle. Kupffer cells and sinusoidal cells sustain hepatocytes growth by producing respectively HGF acting through c-met receptor and EGF. EGFR ligands other than EGF (FGF, VEGF, PDGF and others) act as signal modulators. Growth factors binding to their specific receptors lead to cell growth mainly through the PI3K/PDK1/AKT pathway. The termination phase takes place when the original weight of the liver is reached and results from inhibition of proliferation and growth, and apoptosis induction. The mTOR pathway controls protein translation and together with TGF-β induces hepatocyte expansion inhibition. Apoptosis cooperates with other inhibitory signals, allowing the correct attainment of liver mass. The hepatostat is responsible for the perfect integration of such processes leading liver structural and functional recovery. ECM deposition is a transitory and reversible condition of the regenerative response that arises during the proliferative phase and leads to fibrosis. ECM accumulation requires its rapid and continuous degradation and remodelling to ensure resolution, avoiding cirrhosis outcome and/or liver failure.

Figure 1. Schematic overview of liver regeneration. LR (liver regeneration) outlined in three phases: initiation, proliferation and termination. In the initiation phase different PAMPs trigger regenerative process by interacting with TLRs exposed on Kupffer cells membrane. Tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6 produced by Kupffer cells activates the NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) pathway in hepatocytes making them responsive to the proliferative signalling and forthcoming to G0/G1 transition. Once IL-6 determined the activation of proliferation, acting on JAK/STAT3 pathway, hepatocytes enter the G1 phase and growth factors signalling ensures their progression in the cell cycle. Kupffer cells and sinusoidal cells sustain hepatocytes growth by producing respectively HGF acting through c-met receptor and EGF. EGFR ligands other than EGF (FGF, VEGF, PDGF and others) act as signal modulators. Growth factors binding to their specific receptors lead to cell growth mainly through the PI3K/PDK1/AKT pathway. The termination phase takes place when the original weight of the liver is reached and results from inhibition of proliferation and growth, and apoptosis induction. The mTOR pathway controls protein translation and together with TGF-β (transforming growth factor-beta) induces hepatocyte expansion inhibition. Apoptosis cooperates with other inhibitory signals, allowing the correct attainment of liver mass. The hepatostat is responsible for the perfect integration of such processes leading liver structural and functional recovery. ECM deposition is a transitory and reversible condition of the regenerative response that arises during the proliferative phase and leads to fibrosis. ECM accumulation requires its rapid and continuous degradation and remodelling to ensure resolution, avoiding cirrhosis outcome and/or liver failure. Schematic overview of liver regeneration. LR outlined in three phases: initiation, proliferation and termination. In the initiation phase different PAMPs trigger regenerative process by interacting with TLRs exposed on Kupffer cells membrane. TNF-α and IL-6 produced by Kupffer cells activates the NF-κB pathway in hepatocytes making them responsive to the proliferative signalling and forthcoming to G0/G1 transition. Once IL-6 determined the activation of proliferation, acting on JAK/STAT3 pathway, hepatocytes enter the G1 phase and growth factors signalling ensures their progression in the cell cycle. Kupffer cells and sinusoidal cells sustain hepatocytes growth by producing respectively HGF acting through c-met receptor and EGF. EGFR ligands other than EGF (FGF, VEGF, PDGF and others) act as signal modulators. Growth factors binding to their specific receptors lead to cell growth mainly through the PI3K/PDK1/AKT pathway. The termination phase takes place when the original weight of the liver is reached and results from inhibition of proliferation and growth, and apoptosis induction. The mTOR pathway controls protein translation and together with TGF-β induces hepatocyte expansion inhibition. Apoptosis cooperates with other inhibitory signals, allowing the correct attainment of liver mass. The hepatostat is responsible for the perfect integration of such processes leading liver structural and functional recovery. ECM deposition is a transitory and reversible condition of the regenerative response that arises during the proliferative phase and leads to fibrosis. ECM accumulation requires its rapid and continuous degradation and remodelling to ensure resolution, avoiding cirrhosis outcome and/or liver failure.

Figure 1. Schematic overview of liver regeneration. LR (liver regeneration) outlined in three phases: initiation, proliferation and termination. In the initiation phase different PAMPs trigger regenerative process by interacting with TLRs exposed on Kupffer cells membrane. Tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6 produced by Kupffer cells activates the NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) pathway in hepatocytes making them responsive to the proliferative signalling and forthcoming to G0/G1 transition. Once IL-6 determined the activation of proliferation, acting on JAK/STAT3 pathway, hepatocytes enter the G1 phase and growth factors signalling ensures their progression in the cell cycle. Kupffer cells and sinusoidal cells sustain hepatocytes growth by producing respectively HGF acting through c-met receptor and EGF. EGFR ligands other than EGF (FGF, VEGF, PDGF and others) act as signal modulators. Growth factors binding to their specific receptors lead to cell growth mainly through the PI3K/PDK1/AKT pathway. The termination phase takes place when the original weight of the liver is reached and results from inhibition of proliferation and growth, and apoptosis induction. The mTOR pathway controls protein translation and together with TGF-β (transforming growth factor-beta) induces hepatocyte expansion inhibition. Apoptosis cooperates with other inhibitory signals, allowing the correct attainment of liver mass. The hepatostat is responsible for the perfect integration of such processes leading liver structural and functional recovery. ECM deposition is a transitory and reversible condition of the regenerative response that arises during the proliferative phase and leads to fibrosis. ECM accumulation requires its rapid and continuous degradation and remodelling to ensure resolution, avoiding cirrhosis outcome and/or liver failure. Schematic overview of liver regeneration. LR outlined in three phases: initiation, proliferation and termination. In the initiation phase different PAMPs trigger regenerative process by interacting with TLRs exposed on Kupffer cells membrane. TNF-α and IL-6 produced by Kupffer cells activates the NF-κB pathway in hepatocytes making them responsive to the proliferative signalling and forthcoming to G0/G1 transition. Once IL-6 determined the activation of proliferation, acting on JAK/STAT3 pathway, hepatocytes enter the G1 phase and growth factors signalling ensures their progression in the cell cycle. Kupffer cells and sinusoidal cells sustain hepatocytes growth by producing respectively HGF acting through c-met receptor and EGF. EGFR ligands other than EGF (FGF, VEGF, PDGF and others) act as signal modulators. Growth factors binding to their specific receptors lead to cell growth mainly through the PI3K/PDK1/AKT pathway. The termination phase takes place when the original weight of the liver is reached and results from inhibition of proliferation and growth, and apoptosis induction. The mTOR pathway controls protein translation and together with TGF-β induces hepatocyte expansion inhibition. Apoptosis cooperates with other inhibitory signals, allowing the correct attainment of liver mass. The hepatostat is responsible for the perfect integration of such processes leading liver structural and functional recovery. ECM deposition is a transitory and reversible condition of the regenerative response that arises during the proliferative phase and leads to fibrosis. ECM accumulation requires its rapid and continuous degradation and remodelling to ensure resolution, avoiding cirrhosis outcome and/or liver failure.