2. Immune Response to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis

Immune response to Mtb comprises different mechanisms of the innate and adaptive immune response. A characteristic feature of Mtb is its ability to live inside professional phagocytes, which normally eliminates the captured bacteria and activates cells of adaptive immunity. In this connection, the Mtb

–host cell interaction greatly affects both the disease progression and immune response. These points are important for understanding the action of vaccines, especially live vaccines as BCG.

2.1. Interaction of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis with A Host Cell

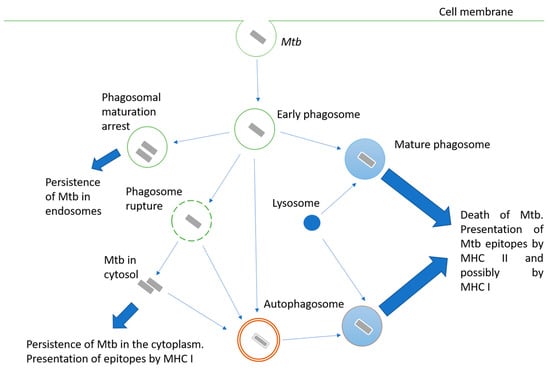

Mycobacteria are intracellular pathogens; they invade alveolar epithelial cells, macrophages, and other phagocytes. When phagocytes engulf Mtb, the mechanisms aimed at destroying the pathogen are triggered, but Mtb may interfere with them and use the engulfing cell as a habitat. Possible options for the fate of the engulfed mycobacterium are shown in

Figure 1. The successful maturation of the phagosome usually results in the death of the bacteria. The main antimicrobial mechanisms of the macrophage mature phagosome include luminal acidification, the production of antimicrobial peptides, the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, and, finally, the degradation of enzymes such as cathepsins

[3]. Peptides are processed in phagosomes for their presentation in complex with MHC II

[4]. Additionally, cross-presentation by MHC I is possible

[5].

Figure 1. Intracellular fate of a bacterium engulfed by a phagocyte. Description is in the text.

Inhibiting phagosome maturation in macrophages ensures the efficient intracellular multiplication of mycobacteria, especially at the beginning of infection. Mtb products involved in phagosome maturation arrest include cell wall components such as lipoarabinomannan (LAM)

[6], glycolipid trehalose-6,6’-dimycolate (TDM; cord factor)

[7], and proteins such as protein kinase PknG

[8], phosphatase SapM

[9], zinc metalloprotease Zmp1

[10], and urease UreC

[11].

Another pathway for Mtb survival in the phagocyte cell is the destruction of the phagosome membrane and its exit into the cytoplasm

[12]. The main effector of this process is the ESAT-6 protein, a pore-forming protein secreted via the ESAT-6 secretion system (ESX-1). Therefore, BCG and other mycobacteria, carrying attenuating mutations at the ESX-1 locus, are unable to penetrate the cytoplasm. The penetration of bacterial proteins into the cytoplasm activates their processing for presentation by MHC class I

[13].

Since Mtb is able to avoid death in the phagolysosome, autophagy plays an important role in bacterial elimination. Autophagosomes are two-membrane structures surrounding cell components or intracellular pathogens

[14]. The fusion of lysosomes with autophagosomes provides an acidic environment for hydrolases, including cathepsin D, oxidases, inducible NO synthase, and antibacterial peptides to kill Mtb and degrade it. Thus, autophagy functions as a second line of defense against pathogens that overcome phagosome-mediated destruction in phagocytes. However, Mtb has developed defense mechanisms against it as well. For instance, ESAT-6 and secreted acid phosphatase SapM have been shown to block autophagosome and lysosome fusion in macrophage-like Raw cells 264.7

[15][16][15,16].

An important consequence of mycobacteria entering the cytosol of the host cell is their interaction with cytosolic innate immunity receptors, leading to the activation of the inflammasome

[17]. Inflammasomes are complex intracellular structures composed of several proteins that include cytosolic receptors such as AIM2-like receptors (ALRs) or NOD-like receptors (NLRs), adaptor proteins, and effector proteins. Classically activated inflammasomes cleave procaspase 1, converting it to active caspase 1. Caspase 1 carries out the processing and maturation of the important proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18

[18].

Cytokines of the IL-1 family play a critical role in the protection against TB. IL-1R knockout in mice led to early lethality after aerosol low-dose infection with Mtb

[19]. At the same time, inflammasome dysfunction was found to have less of an impact, which indicates that caspase 1-independent pathways for IL-1β activation can be implemented in TB

[20].

The mechanisms of cell death following Mtb infection have different consequences for the host. In classical necrosis, the affected cell swells and bursts, causing acute inflammation. The leakage of cell content during necrosis promotes the spread of bacteria

[21]. Apoptosis is a generally caspase-mediated cascade of reactions that result in cytoskeleton collapse, DNA fragmentation, the disassembly of cellular components, and packaged cell content into membrane-surrounded apoptotic bodies. There are at least three ways to trigger apoptosis: the interaction of some members of the TNF family with their receptors, cellular stress leading to the disruption of the outer mitochondrial membrane, and the action of granzyme B released by cytotoxic cells. It is generally accepted that apoptosis is an effective defense mechanism against Mtb

[22]. Cell apoptosis promotes bacterial death, and apoptotic bodies containing bacteria can be taken up by other antigen-presenting cells and are presented in MHC I by a cross-presentation mechanism

[21].

2.2. Adaptive Immunity to Mtb

Adaptive immunity is important for the containment of the infection. It is mainly mediated by T-cells. The activation of naive T-lymphocytes occurs in lung-draining lymph nodes where dendritic cells and, to a lesser extent, macrophages locate and present antigens as processed epitopes in complex with MHC I or MHC II

[23]. The main effector cells of adaptive immunity against TB are CD4 T-lymphocytes. Mice deficient in these cells are significantly more susceptible to infection than wild-type or CD8 T-cell-deprived mice

[24]. When CD4 T-cell deficiency develops due to HIV, the possibility of TB activation dramatically increases as well as the severity of the disease

[25]. CD8-lymphocytes are also involved in the immune response to Mtb

[26]. Their functions include IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxic action on the infected cells.

Specific CD4 T-cells can form different populations. Th1 lymphocytes are critical as major producers of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2. The genetic dysfunction of IFN-γ leads to the high sensitivity of mycobacteria

[27]. The cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α promote the activation of infected phagocytes and intracellular elimination of bacteria; they induce autophagy, whereas Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13 inhibit it, thereby interfering with the autophagic elimination of the intracellular pathogen

[14]. Th17 cells and their main effector, cytokine IL-17, are also important in immune response and may ensure IFN-γ-independent protection against Mtb

[28]. Th17 cells provide protection against Mtb infection in adoptive transfer models in IFN-γ-deficient mice, which was reflected by a greater survival and lower bacterial burden. Finally, regulatory T-cells (T reg) secrete IL-10 and TGF-β, which suppress immune response activity and thus can protect tissues from excessive inflammation. During the initial T-cell response to Mtb infection, Mtb induces T reg cell expansion, which delays the onset of adaptive immunity, allowing Mtb to replicate in the lungs until T cells finally arrive

[29].

There is no unequivocal opinion on the role of humoral immunity in the protection against the development of TB. It is known that patients with a defective antibody production mechanism and/or patients deficient in B-lymphocytes are not particularly at risk of TB infection, and passive immunization provides no protection. However, several groups have found that monoclonal antibodies against certain cell wall components can modify various aspects of mycobacterial infections

[30]. Thus, the immune response to Mtb involves a complex interaction of innate and adaptive immunity mechanisms.

2.3. Immune Response and Protection Induced by BCG Vaccination

The only vaccine currently used in clinical practice is BCG. It was obtained through the long-term cultivation of pathogenic

Mycobacterium bovis in poor media, leading to the loss of several gene loci. The latter are known as regions of difference (RD) and include some sequences that are important for virulence (primarily RD1). A number of other gene rearrangements occurred during subsequent cultivation, resulting in the appearance of different sub-strains, which have some differences in the level of protectiveness and residual virulence

[31].

The BCG vaccination is administered in infancy in high-burden countries. BCG protection from disseminated TB and tuberculous meningitis, the two most severe forms of TB in children, is reliably proven

[32]. In addition, the effect of BCG on nonspecific immunity and resistance to other infections has attracted a lot of interest lately

[33]. For instance, BCG vaccination significantly reduces overall infant mortality

[34]. A possible reason for this is the stimulation of nonspecific immunity, resulting in enhanced resistance to respiratory diseases

[35]. Other nonspecific effects of BCG include an increase in antiviral immunity through the intensified production of IL-1B

[36] and IFN-γ

[37]. The immunostimulatory properties of BCG have also found use in the therapy of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer with a high risk of recurrence or progression

[38]. BCG reveals the anti-tumor activity and is considered the gold standard of treatment for this type of tumor

[39]. Its action is based on the recruitment of CD4+ T-cells, neutrophils, and lymphocytes and the activation of immune cells to eliminate cancer

[40]. An important mechanism of the nonspecific effect of BCG in the immune response to this one and several other diseases is heterologous immune memory, which is mediated by epigenetic reprogramming and is stimulated by BCG. This phenomenon is called “trained immunity”

[41].

An analysis of current epidemiologic data on COVID-19 infection revealed a correlation between BCG vaccination and decreased morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 worldwide

[42]. It was found that countries not practicing BCG vaccination, such as Italy, the Netherlands, and the USA, suffered more from the pandemic than countries with common BCG vaccination policies. Countries with late BCG vaccination put into clinical practice, such as Iran (1984), suffered from a higher mortality rate. This supports the hypothesis that BCG is effective in protecting the elderly population. BCG vaccination has been shown to provide broad protection against viral infections and sepsis

[33], so it is likely that the protective effect of BCG may not be directly related to protection against COVID-19. Nevertheless, due to the correlation between BCG vaccination and a mortality decrease in reported COVID-19 cases, there is reason to believe that BCG may provide some protection directly against COVID-19.

The intradermal BCG vaccination of infants has been found to produce functions specific to mycobacteria CD4 and, to a lesser extent, CD8 cells

[43]. BCG protectivity decreases with age despite the fact that healthy, BCG-vaccinated children of different ages produce effector CD4+ T-cell responses. This may be due to a weakening of BCG-specific proliferation and the expansion of effector CD4 T-cells with age, which is associated with an increase in regulatory T-cells.

[44]. In addition, normal effector T-cell responses, as determined by IFN-γ production, do not necessarily correlate with protective immunity

[45].

BCG vaccination can protect against infection with Mtb. The meta-analysis of six studies (n = 1745) showed the effectiveness of BCG-induced protection against infection was 27% compared with 71% against active TB. Among those infected, protection against disease progression was 58%. The effectiveness of the protection against infection among vaccinated children based on 14 studies was 19% compared to unvaccinated children

[46].

A key problem with BCG is its varying efficacy. Additionally, BCG has little or no effect on the spread of pulmonary TB in adults. Geographic location, prior exposure to nontuberculous mycobacteria, and the rate of attenuation of BCG are considered factors that influence the effectiveness of BCG

[47]. Thereby, scientists all around the world have been developing new vaccines that could provide more effective protection. An increased understanding of the mechanisms of immune defense against TB and the development of genetic engineering methods have allowed the creation of a large number of candidate vaccines that are considered a potential replacement for BCG.