Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Madhu Thomas.

Supramolecular architectures, which are formed through the combination of inorganic metal cations and organic ligands by self-assembly, are one of the techniques in modern chemical science. This kind of multi-nuclear system in various dimensionalities can be implemented in various applications such as sensing, storage/cargo, display and molecular switching. Iron(II) mediated spin-crossover (SCO) supramolecular architectures with Schiff bases have attracted the attention of many investigators due to their structural novelty as well as their potential application possibilities.

- iron(II)

- supramolecular

- Schiff base

1. Introduction

Supramolecular coordination complexes (SCC), metal-organic frameworks (MOF), or discrete metal-organic assemblies (DMOA) are some of the pioneers in modern chemical structures that break the boundaries between inorganic metal cations and organic ligands [1,2][1][2]. The architecture of these supramolecular compounds shows great potential to create new variable molecules and materials that have diverse applications (Figure 1) [3,4,5,6][3][4][5][6]. In metal-mediated supramolecular architectures, the self-assembled structures can be arrived at through non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonds [7,8][7][8], halogen bonds [9[9][10],10], π-π interactions [11[11][12],12], and coordination bonds [13,14][13][14]. The chemical and physical interactions of different strengths and varying degrees of geometrical preferences are important to design and creating different structures [15].

Figure 1. Applications of supramolecular complexes in host-guest chemistry.

Metal-mediated architecture in supramolecular chemistry is one of the combinations of metal ions and organic ligands by self-assembly through coordination bonds [16]. The strength of the coordinate bond between metal ions and organic ligands shows both steady and dynamic character in sophisticated environments since its strength lies between weak noncovalent and covalent interactions [17]. In supramolecular chemistry, metal ions and organic linkers can be coordinated by Lewis acid/base interactions [18]. The basic aspects in metal-mediated supramolecular architectures during self-assembly are their adjustability to be designed as needed and their rational combinations of metal–ligand coordination for specific purposes, which can make them unique for many applications [19,20][19][20].

In the field of supramolecular chemistry, metal ions are being extensively used because of their inimitable capacity to organize molecules or atoms in a unique geometry [21,22][21][22]. Coordinating metal ions to organic linkers in supramolecular compounds has a great role in the adjustment of self-assembly and to modify the morphologies of the resulting supramolecular architectures. The metal ions, along with the binding ligands, determine the properties of the metal-coordinated supramolecular array because various metal ions differ in size, binding affinity, coordination geometry, coordination number and charge density [23,24][23][24].

2. Schiff Base Ligand System in Supramolecular Architectures

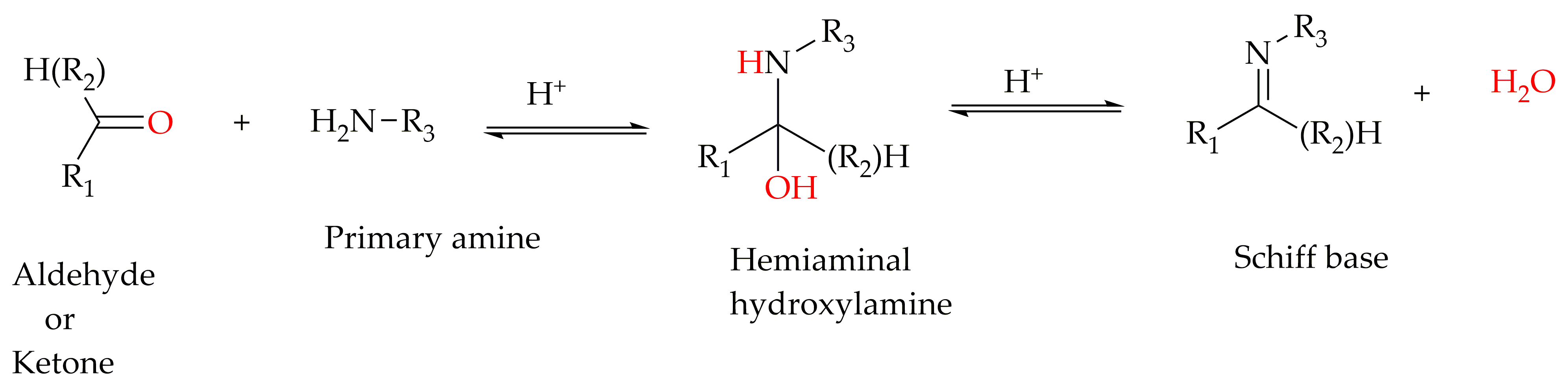

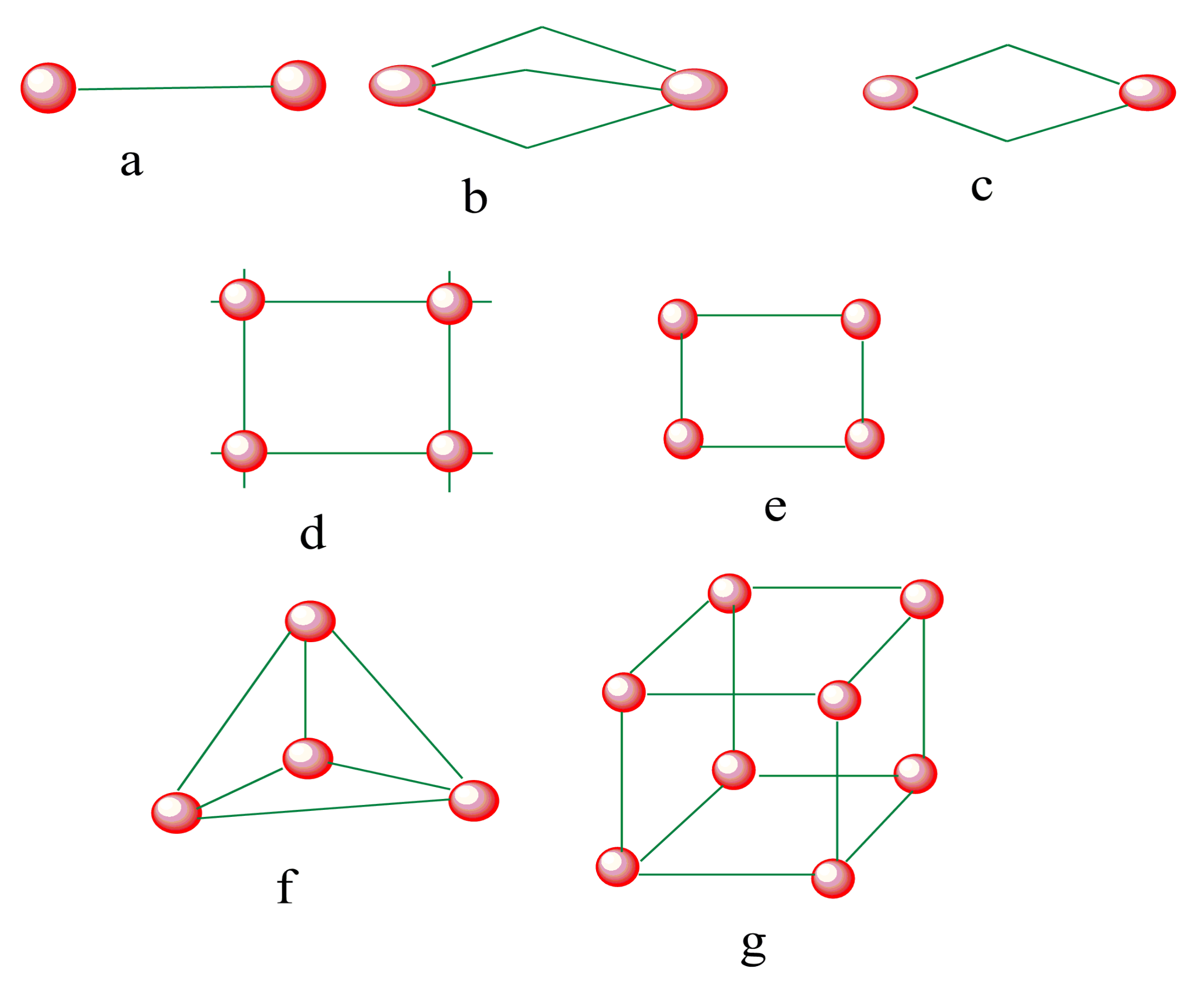

Schiff bases, named after Hugo Schiff [25], are organic ligands that are synthesized from primary amines and carbonyl compounds (aldehydes/ketones) and known as imine or azomethine. Structurally, a Schiff base is an analogue of a ketone or aldehyde in which the carbonyl group (-C=O) is converted by a primary amine into an imine or azomethine (-HC=N-) functionality [26] (Scheme 1). Schiff bases are well-known ligands in constructing supramolecular architecture and other complexes through coordination bond, hydrogen bond, halogen bond or π-π interactions [27]. Because of the simple reaction conditions to promote the synthesis of a wide variety of Schiff base ligands with different chelating abilities, flexibility or chirality, they are widely used to design and construct supramolecular architecture for specific purposes [27]. Moreover, depending on the shape of the formyl and amine precursors and/or the metal-ion template used, the supramolecular architecture of the macrocyclic molecules of helicate/meso-helicate/spiral, grid/square cage and cube-containing imine groups can be formed through cyclization reactions as well. Schiff bases are classical organic ligands for the metal ions of p, d, and f blocks, which have significantly contributed to the development of coordination chemistry on both basic and application aspects [28].

Scheme 1. General schematic synthesis of Schiff base ligands.

3. Magnetic Properties of Iron(II) Spin-Crossover Schiff Base Supramolecular Architectures

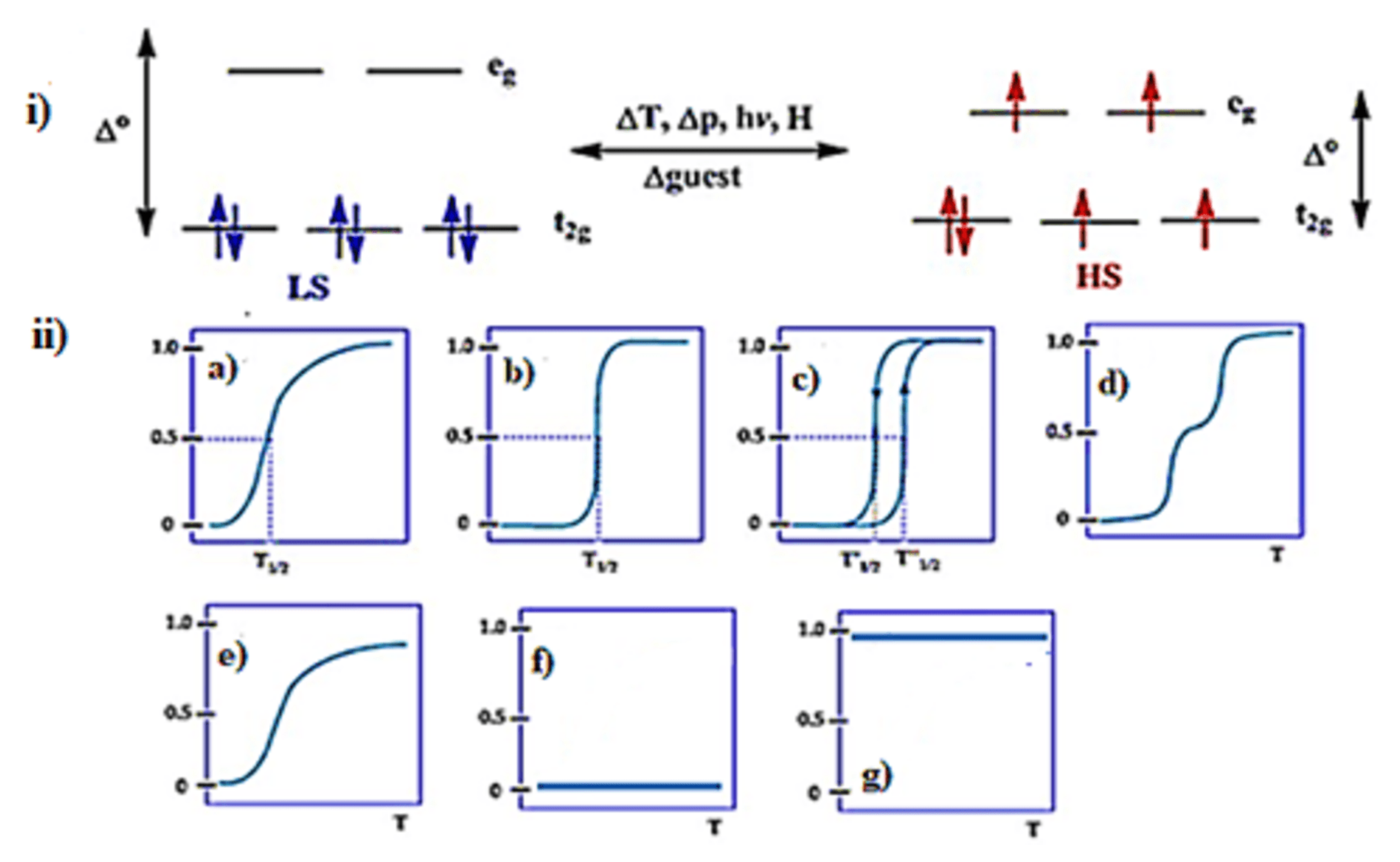

SCO supramolecular complexes are a fascinating class of materials revealing molecular bi-stability with their varying potential applications [29]. The molecular bi-stability is due to the ability of electronic state switching between high spin (HS) and low spin (LS) when external stimuli such as change in temperature, pressure, light irradiation or guest presence/absence occurs [30]. SCO can be observable for octahedral 3d transition metal (3d4–3d7) ions. There are two ways of electron distributions in the t2g and eg orbitals of octahedral iron(II) complexes. Depending on the nature of the ligand field splitting energy and pairing energy (P), electrons can be populated, as shown in (Figure 2i). When a strong ligand field is applied, there will be large Δo, and electrons will remain in the lower energy state of the t2g set and pair up, and it is a LS state (Δo > P), thus diamagnetic complexes can be observed. On the other hand, if weak field ligands are applied, Δo is small due to a very small energy difference between the t2g and eg sets and the maximum number of unpaired electrons, i.e., the HS state occurs (Δo < P) [31].

Figure 2. (i) The d orbital splitting diagram for an octahedral iron(II) ion. (ii) Various types of SCO behavior: (a) gradual (b) abrupt (c) with hysteresis (d) two-step transition (plateau) (e) incomplete (f) low spin and (g) high spin. Reproduced with modification with permission from [32]; Published by Royal Society of Chemistry, 2019.

Figure 3. SCO-active complexes of di-nuclear (a–c); grid (d), square (e), tetrahedral cage (f), octahedral cube (g). Green = di- to polydentate of N-donor and O-donor Schiff base ligands. Red = iron (II) metal centers.

Iron(II) SCO Compounds with Spiral Architectures

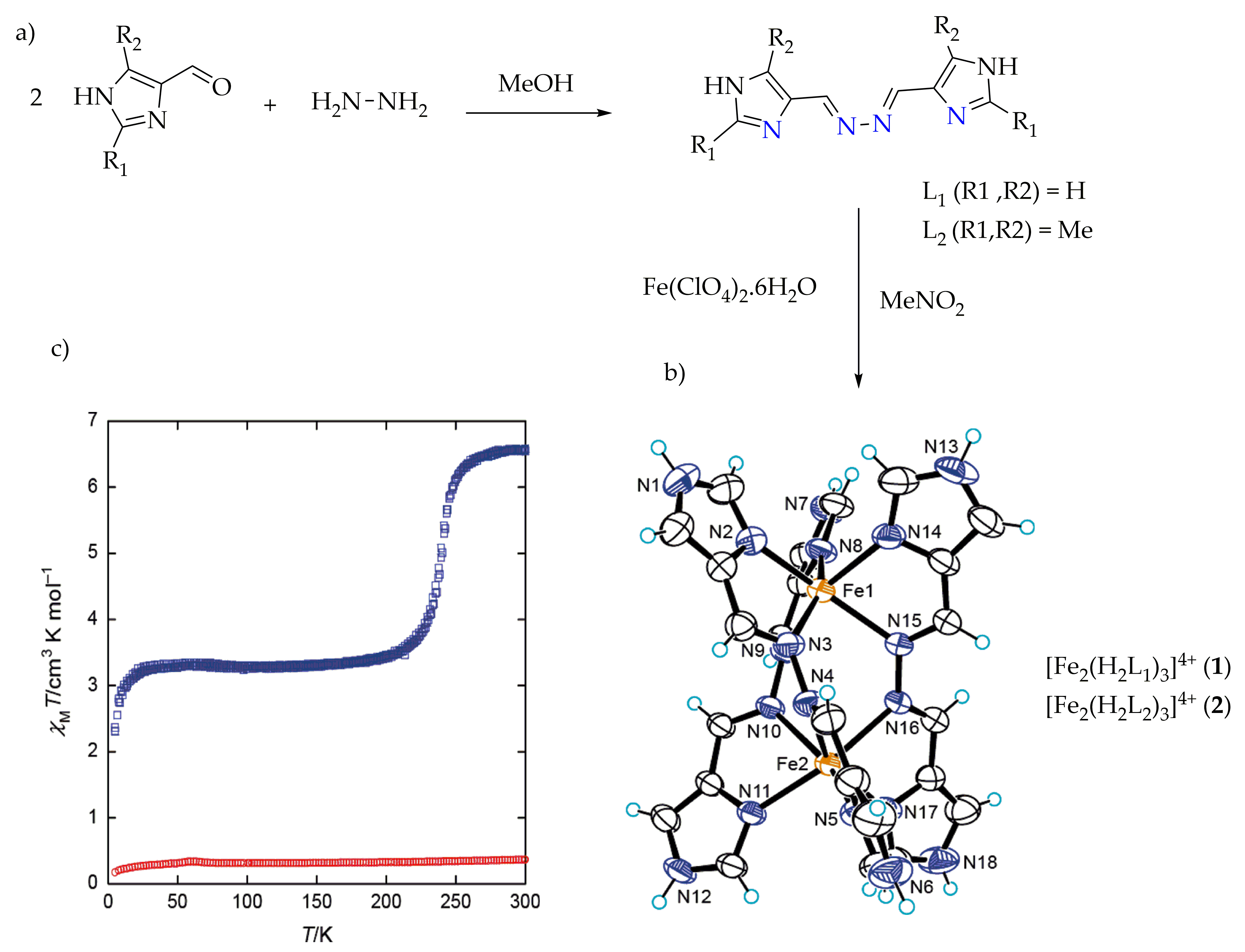

Spiral architectures of iron(II) are an interesting area to investigate due to the fascinating structure and cooperative SCO behavior, as metal centers in those will lead up to three different spin states LS-LS, LS-HS and HS-HS [54,55,56][54][55][56]. These spin states can be related to cooperativity. Negative cooperativity can lead to a two-step spin transition, as the first SCO can stabilize the LS-HS mixed spin state in (Figure 2d) and the second SCO takes place at different temperatures. Spiral iron(II) SCO architectures are interesting due to the fact that they have three-dimensional structures. As positive cooperativity occurs between metal centers, the SCO behaviors have been found in different forms compared as mononuclear analogues [32,54,55,56][32][54][55][56]. Positive cooperativity can lead to one-step spin switching of both metal centers (i.e., [HS-HS] to [LS-LS] or vice versa) in which a sharp, abrupt and/or hysteretic loop SCO can be attained (Figure 2b,c) [57,58,59,60][57][58][59][60]. Recently, a helicate-like di-nuclear macrocyclic Schiff base iron(II) complex was reported by Zhang et al. [61] showing an antiferromagnetic interaction between the metal centers. In the literature, there have been many iron(II) macrocyclic Schiff base complexes reported [61,62,63,64,65,66][61][62][63][64][65][66] which were not formed by self-assembly and did not show any SCO properties. Kojima et al., reported on the SCO of spiral iron(II) complexes of L1 and L2 of (Chart 1) [57,59][57][59]. The di-nuclear spiral iron(II) complexes [Fe2(H2L1)3]4+ (1), [Fe2(H2L2)3]4+ (2) were synthesized by the reaction of respective ligands (Figure 4a) and Fe(ClO4)2·6H2O in nitromethane in a 3:2 molar ratio (Figure 4b). The magnetic behaviors of complexes (1) and (2) are shown in (Figure 4c). The complex from L2 stayed in the LS state over the entire temperature range, and this result is in accordance with the strong ligand field strength of H2L2 caused by the presence of electron-donating methyl groups. The complex from L1 exhibited an abrupt SCO behavior at about 240 K.

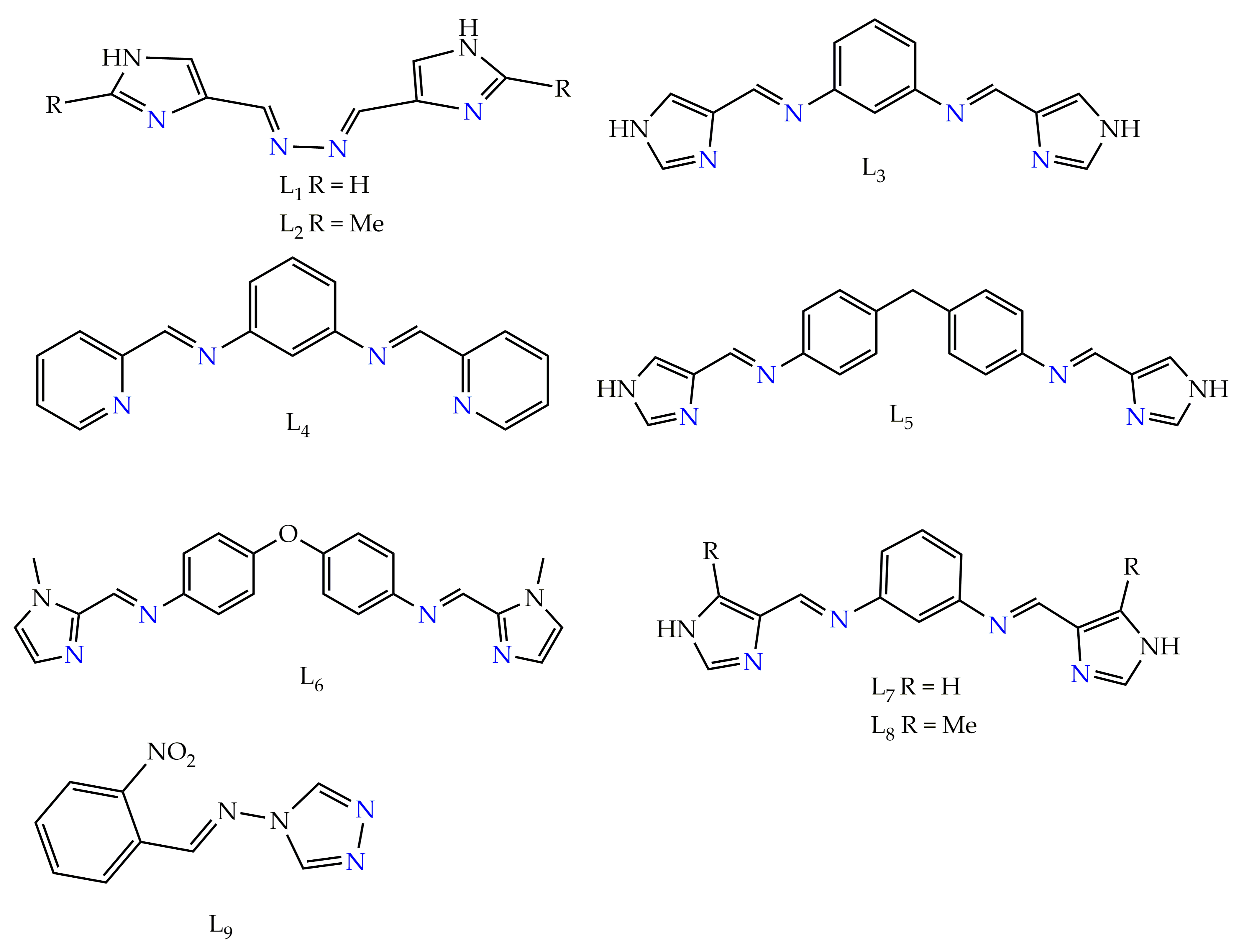

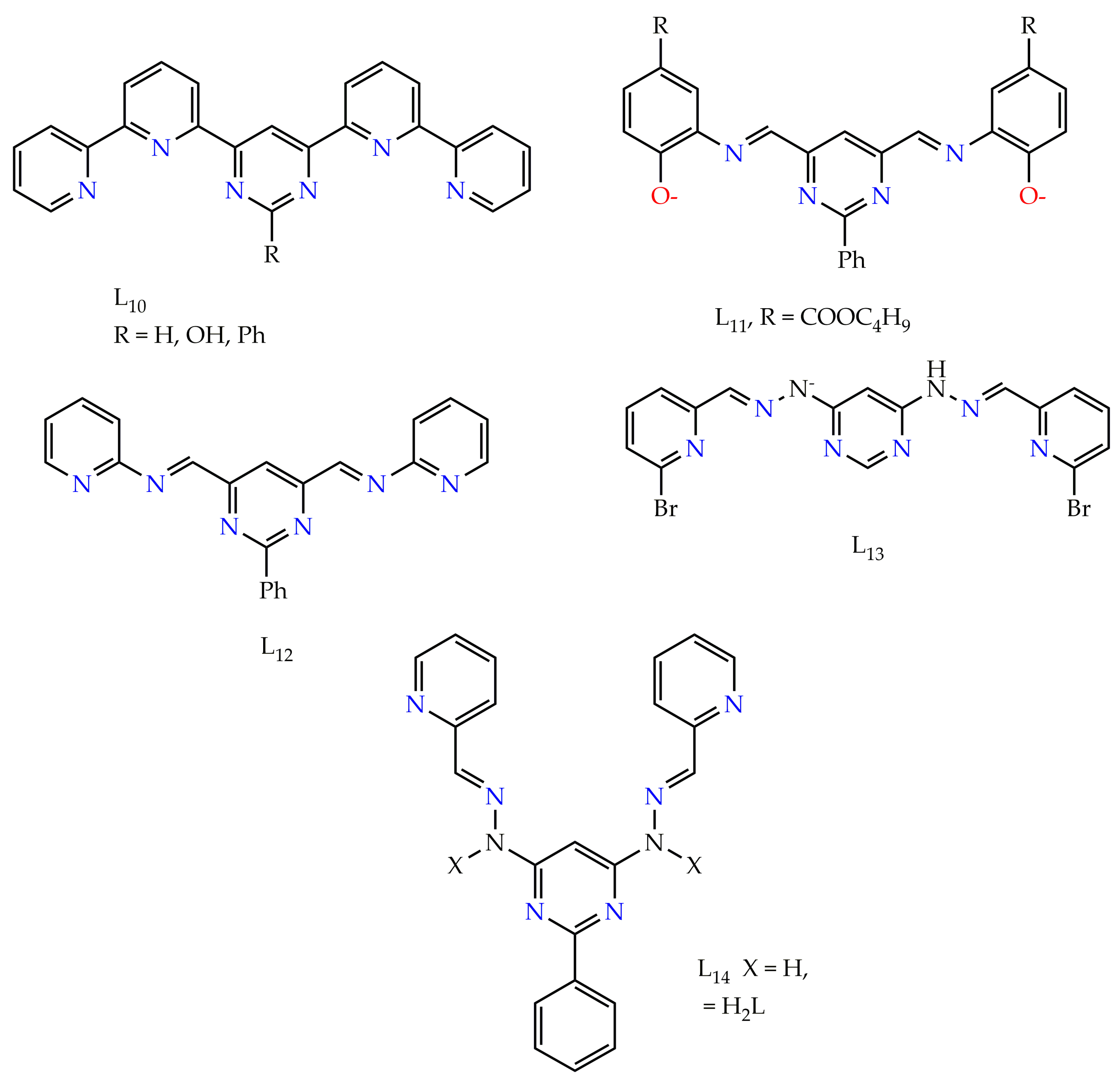

Chart 1. Ligands known to form SCO-active iron(II) dinuclear supramolecular architectures. Blue = binding pocket of the ligand to central metal.

Figure 4. (a) L1 and L2 used to synthesize spiral iron(II) complexes. (b) X-ray molecular structure of the cation of complexes (1) and (2). Color code: orange = Fe; blue = N; black = C; light blue = H. (c) Magnetic behaviors of complex (1), (blue) and (2) (red) in the form of a χMT vs. T plot.

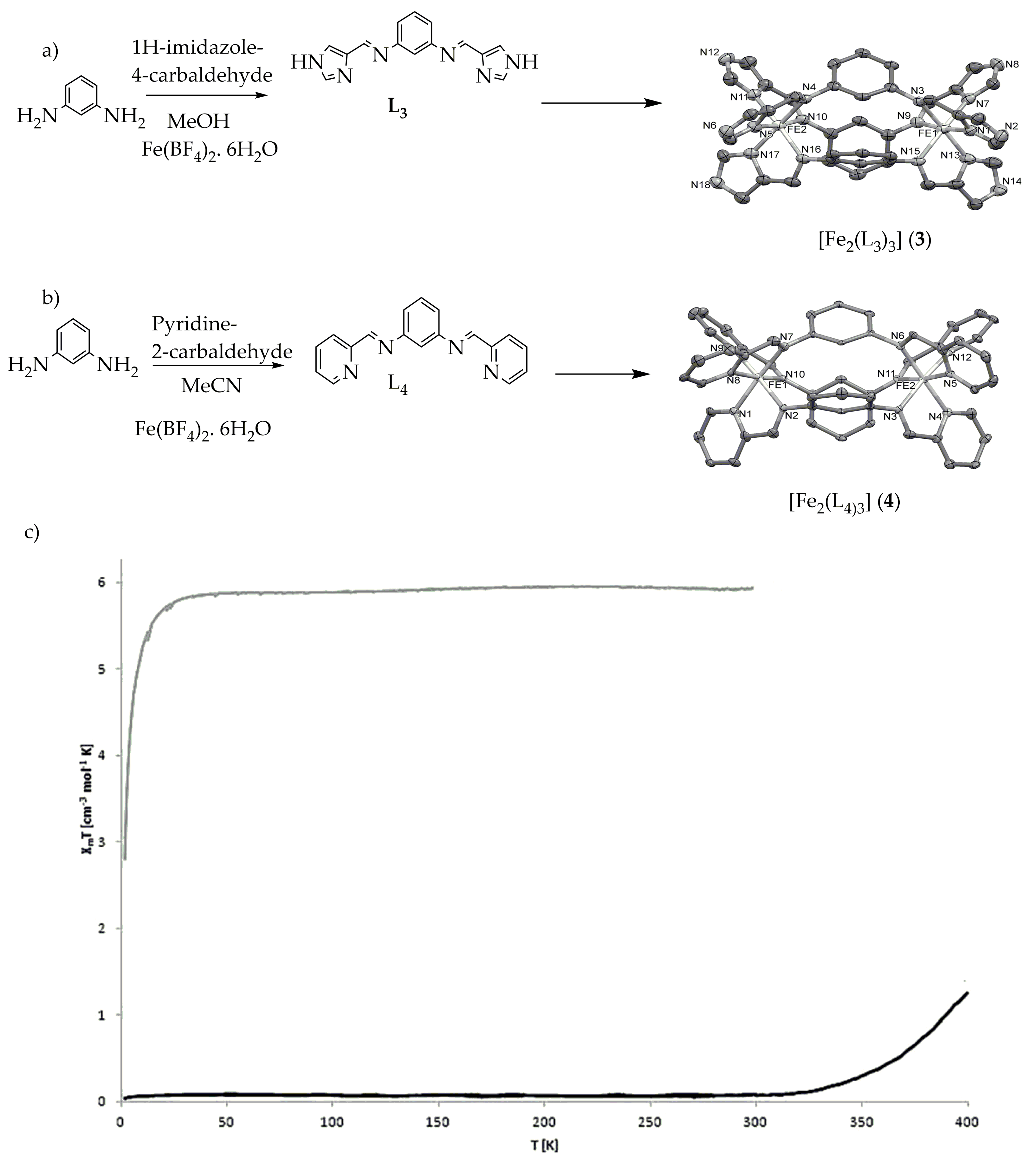

Figure 5. (a) [Fe2(L3)3] (3) [L3 = N,N′-bis(1H-imidazol-4-ylmethylene)benzene-1,3-diamine] (b) [Fe2(L4)3] (4) [L4 = N,N′-bis(pyridin-2-ylmethylene)benzene-1,3-diamine] (c) Magnetic behavior of complexes (3) blue line and (4) red line complexes as χMT vs. T plot.

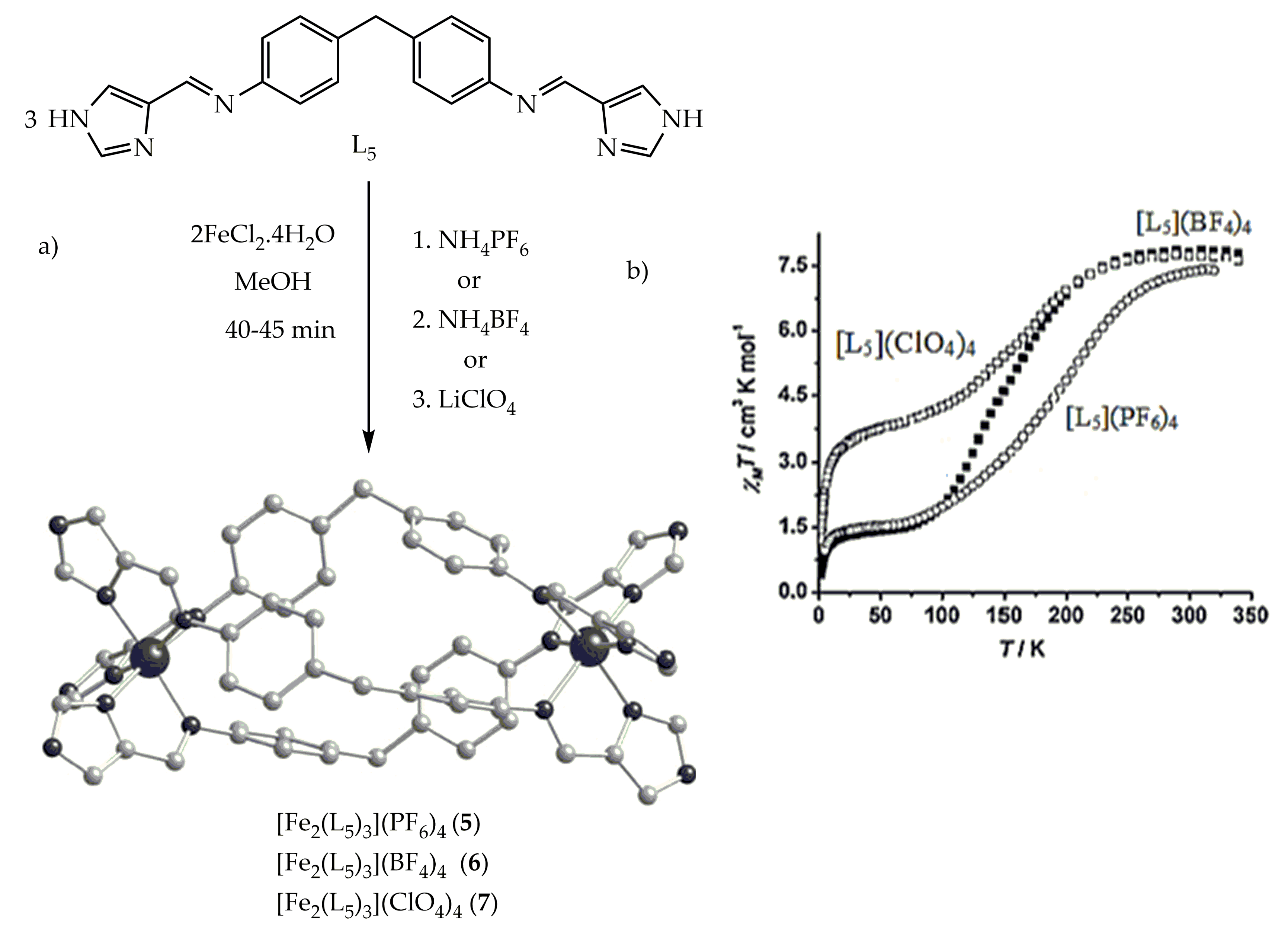

Figure 6. (a) The crystal structure of [Fe2(L5)3]X4 complexes (X= PF6 (5) or BF4 (6) and ClO4 (7) (b). Magnetic susceptibility χMT vs. T plot for spiral complexes of 5, 6 and 7 with different counter anions.

Chart 2.

The three bis-terdentate ligands known to form SCO-active Fe

4

L

4

grids. All ligands provide N

6

and N

4

O

2

donor sets to the octahedral iron(II) centers.

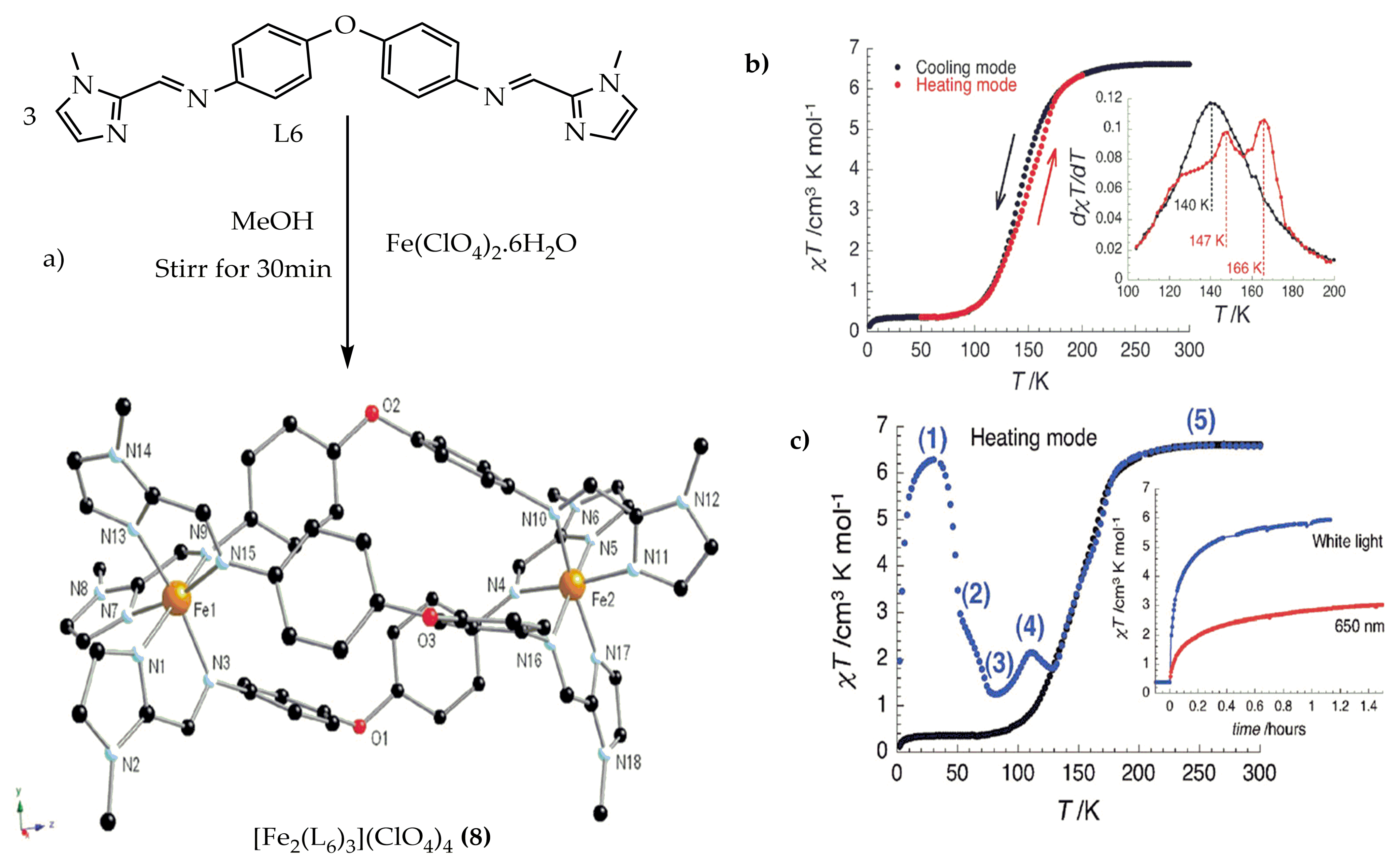

Figure 7. (a) Molecular structure of the triple helicate of complex (8) (b) χMT vs. T plot for 8.2MeCN at 1000 Oe at a sweep rate of 0.6 K/min. Inset: dxT/dT vs. T plot (c) Temperature dependence of the χMT product after white light irradiation at 10 K for (8). Inset: χMT vs. T plot at 10 K under 650 nm and white light irradiations at 10 K (at T sweep rate of 0.6 K/min).

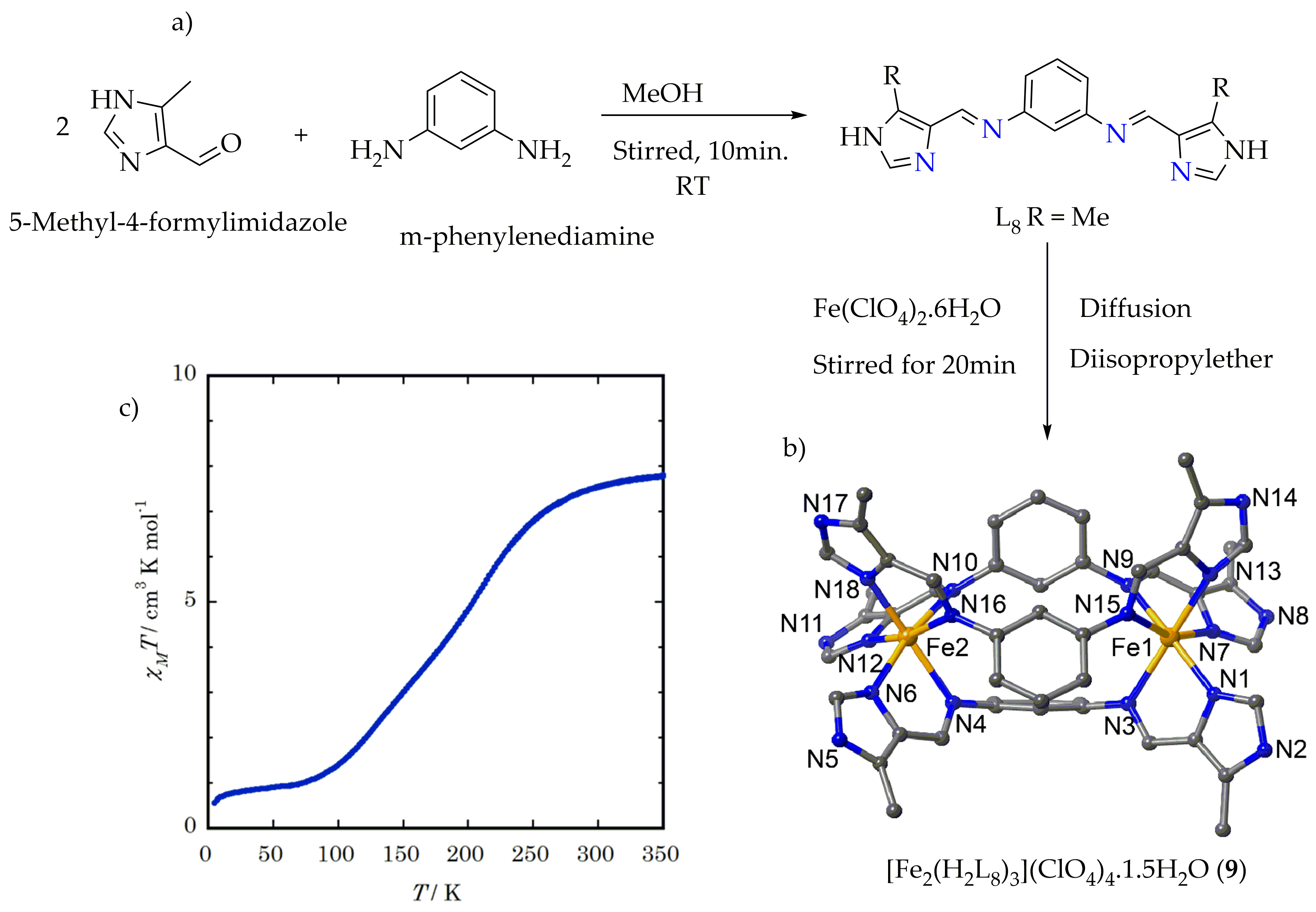

Figure 8. (a) Synthesis root of ligand L8. (b) Crystal structure of the complex 9.1.5H2O. (c) The χMT vs. T plot of desolvated complex 9.

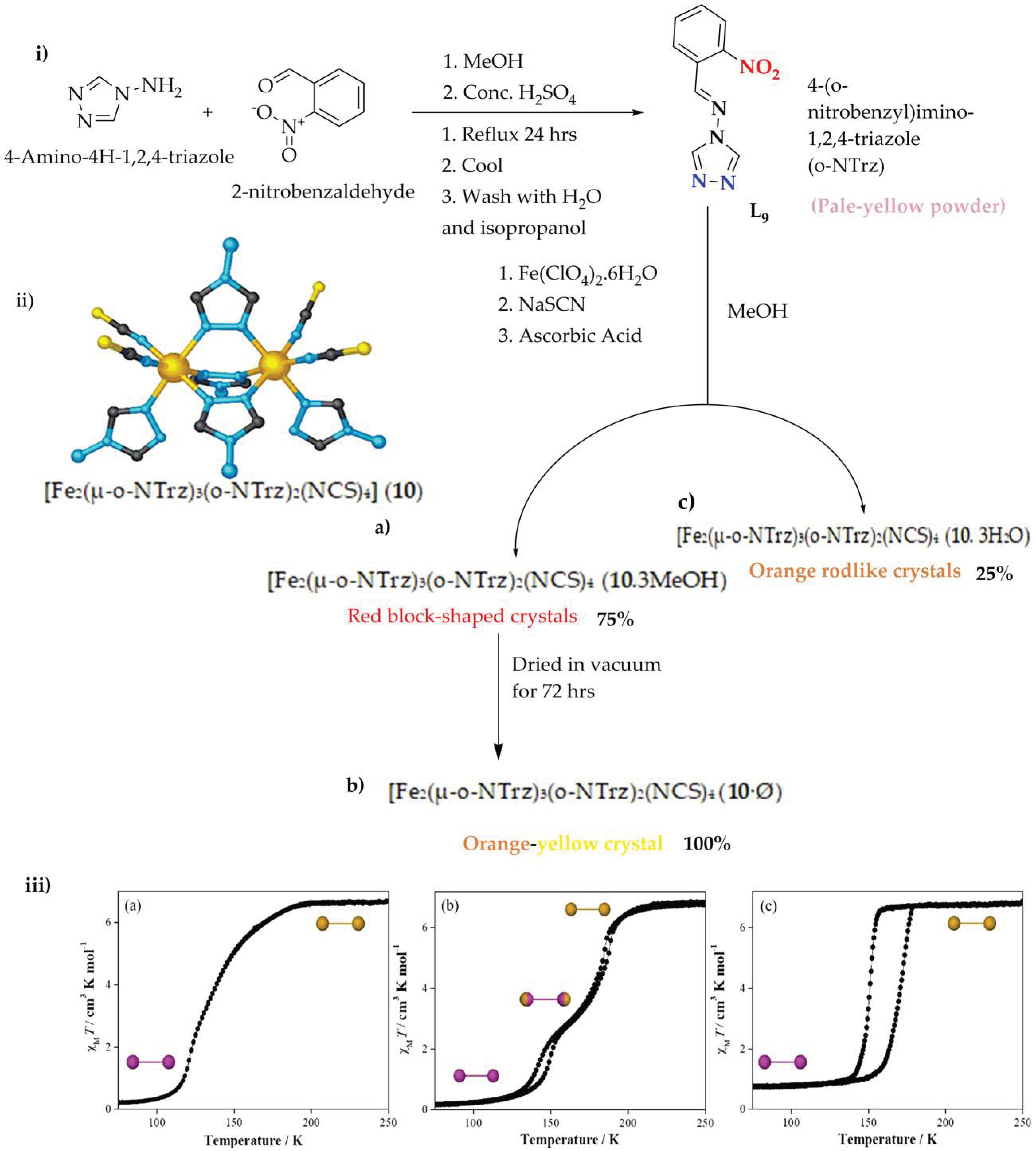

Figure 9. (i) o-NTrz, 4-(onitrobenzyl)imino-1,2,4-triazole (blue: N-Fe binding groups, red: functionality). (ii) Di-nuclear [Fe2(μ-o-NTrz)3(o-NTrz)2(NCS)4] (10) core structure (a) 10·3MeOH, (b) 10·Ø, and (c) 10·3H2O (iii) χMT vs. T plot of the three complexes (a) 10·3MeOH, (b) 10·Ø, and (c) 10·3H2O (250−50−250 K; sweep mode; scan rate: 2 K min−1). Inset: Spin-state per di-nuclear unit at the indicated plateau region, as determined by structural analysis (Fe-Fe; HS: gold; LS: purple).

References

- Savastano, M. Words in Supramolecular Chemistry: The Ineffable Advances of Polyiodide Chemistry. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 1142–1165.

- Sang, Y.; Liu, M. Hierarchical Self-Assembly into Chiral Nanostructures. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 633–656.

- Wang, D.X.; Wang, M.X. Exploring Anion-π Interactions and Their Applications in Supramolecular Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1364–1380.

- Khan, S.B.; Lee, S.L. Supramolecular Chemistry: Host–Guest Molecular Complexes. Molecules 2021, 26, 3995.

- Liu, G.; Sheng, J.; Teo, W.L.; Yang, G.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y. Control on Dimensions and Supramolecular Chirality of Self-Assemblies through Light and Metal Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16275–16283.

- Morimoto, M.; Bierschenk, S.M.; Xia, K.T.; Bergman, R.G.; Raymond, K.N.; Toste, F.D. Advances in Supramolecular Host-Mediated Reactivity. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 969–984.

- Shi, Q.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, W.; Su, X.; Neniškis, A.; Wei, X.; Taujenis, L.; Snarskis, G.; Ward, J.S.; Rissanen, K.; et al. Selective Formation of S4-and T-Symmetric Supramolecular Tetrahedral Cages and Helicates in Polar Media Assembled via Cooperative Action of Coordination and Hydrogen Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 3658–3670.

- Yokoya, M.; Kimura, S.; Yamanaka, M. Urea Derivatives as Functional Molecules: Supramolecular Capsules, Supramolecular Polymers, Supramolecular Gels, Artificial Hosts, and Catalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 5601–5614.

- Basak, T.; Frontera, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Insight into Non-Covalent Interactions in Two Triamine-Based Mononuclear Iron(III) Schiff Base Complexes with Special Emphasis on the Formation of Br⋯π Halogen Bonding. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 1578–1587.

- Li, T.; Pang, H.; Wu, Q.; Huang, M.; Xu, J.; Zheng, L.; Wang, B.; Qiao, Y. Rigid Schiff Base Complex Supermolecular Aggregates as a High-Performance PH Probe: Study on the Enhancement of the Aggregation-Caused Quenching (ACQ) Effect via the Substitution of Halogen Atoms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6259.

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Fu, K.; Liang, J.; Pang, S.; Liu, G. Multiple Chirality Inversion of Pyridine Schiff-Base Cholesterol-Based Metal–Organic Supramolecular Polymers. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 9520–9523.

- Yu, Z.M.; Zhao, S.Z.; Wang, Y.T.; Xu, P.Y.; Qin, C.Y.; Li, Y.H.; Zhou, X.H.; Wang, S. Anion-Driven Supramolecular Modulation of Spin-Crossover Properties in Mononuclear Iron(III) Schiff-Base Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 15210–15223.

- Berdiell, I.C.; Hochdörffer, T.; Desplanches, C.; Kulmaczewski, R.; Shahid, N.; Wolny, J.A.; Warriner, S.L.; Cespedes, O.; Schünemann, V.; Chastanet, G.; et al. Supramolecular Iron Metallocubanes Exhibiting Site-Selective Thermal and Light-Induced Spin-Crossover. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18759–18770.

- Li, W.; Sun, L.; Garcia, Y. Subcomponent Self-Assembly of a Fe(II) Based Mononuclear Complex for Potential NH3 Sensing Applications. Hyperfine Interact. 2021, 242, 7.

- Gilday, L.C.; Robinson, S.W.; Barendt, T.A.; Langton, M.J.; Mullaney, B.R.; Beer, P.D. Halogen Bonding in Supramolecular Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7118–7195.

- Pöthig, A.; Casini, A. Recent Developments of Supramolecular Metal-Based Structures for Applications in Cancer Therapy and Imaging. Theranostics 2019, 9, 3150–3169.

- He, C.; Liu, D.; Lin, W. Nanomedicine Applications of Hybrid Nanomaterials Built from Metal−Ligand Coordination Bonds: Nanoscale Metal−Organic Frameworks and Nanoscale Coordination Polymers. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11079–11108.

- Pei, W.Y.; Lu, B.B.; Yang, J.; Wang, T.; Ma, J.F. Two New CalixResorcinarene-Based Coordination Cages Adjusted by Metal Ions for the Knoevenagel Condensation Reaction. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 9942–9948.

- Liu, P.; Qin, R.; Fu, G.; Zheng, N. Surface Coordination Chemistry of Metal Nanomaterials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 2122–2131.

- El-Sayed, E.S.M.; Yuan, D. Metal-Organic Cages (MOCs): From Discrete to Cage-Based Extended Architectures. Chem. Lett. 2020, 49, 28–53.

- Cook, L.J.K.; Mohammed, R.; Sherborne, G.; Roberts, T.D.; Alvarez, S.; Halcrow, M.A. Spin State Behavior of Iron(II)/Dipyrazolylpyridine Complexes. New Insights from Crystallographic and Solution Measurements. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 289–290, 2–12.

- Rather, I.A.; Wagay, S.A.; Ali, R. Emergence of Anion-π Interactions: The Land of Opportunity in Supramolecular Chemistry and Beyond. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 415, 213327.

- Tomohiro, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Okuno, H.; Kodaka, M. Synthesis and Spectroscopic Analysis of Chromophoric Lipids Inducing PH-Dependent Liposome Fusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 14733–14740.

- Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Ye, J.; Jiao, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, C.; Li, B.; Fu, Y. Metal-Coordinated Supramolecular Self-Assemblies for Cancer Theranostics. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2101101.

- Schiff, H. Mittheilungen Aus Dem Universitätslaboratorium in Pisa: Eine Neue Reihe Organischer Basen. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1864, 131, 118–119.

- Qin, W.; Long, S.; Panunzio, M.; Biondi, S. Schiff Bases: A Short Survey on an Evergreen Chemistry Tool. Molecules 2013, 18, 12264–12289.

- Hameed, A.; al-Rashida, M.; Uroos, M.; Ali, S.A.; Khan, K.M. Schiff Bases in Medicinal Chemistry: A Patent Review (2010–2015). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2017, 27, 63–79.

- Lewiński, J.; Prochowicz, D. Assemblies Based on Schiff Base Chemistry. Compr. Supramol. Chem. II 2017, 6, 279–304.

- Qiu, Y.R.; Cui, L.; Cai, P.Y.; Yu, F.; Kurmoo, M.; Leong, C.F.; D’Alessandro, D.M.; Zuo, J.L. Enhanced Dielectricity Coupled to Spin-Crossover in a One-Dimensional Polymer Iron(II) Incorporating Tetrathiafulvalene. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 6229–6235.

- Gebretsadik, T.; Yang, Q.; Wu, J.; Tang, J. Hydrazone Based Spin Crossover Complexes: Behind the Extra Flexibility of the Hydrazone Moiety to Switch the Spin State. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 431, 213666.

- Lada, Z.G.; Andrikopoulos, K.S.; Polyzou, C.D.; Tangoulis, V.; Voyiatzis, G.A. Monitoring the Spin Crossover Phenomenon of 2D Hofmann-Type Polymer Nanoparticles via Temperature-Dependent Raman Spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2020, 51, 2171–2181.

- Kumar, K.S.; Bayeh, Y.; Gebretsadik, T.; Elemo, F.; Gebrezgiabher, M.; Thomas, M.; Ruben, M. Spin-Crossover in Iron(II)-Schiff Base Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 15321–15337.

- Gütlich, P.; Goodwin, H.A. Spin crossover-An overall perspective. In Spin Crossover in Transition Metal Compounds I. Topics in Current Chemistry; Gütlich, P., Goodwin, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 1–47.

- Kucheriv, O.I.; Fritsky, I.O.; Gural’skiy, I.A. Spin Crossover in FeII Cyanometallic Frameworks. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 521, 120303.

- Turo-Cortés, R.; Valverde-Muñoz, F.J.; Meneses-Sánchez, M.; Muñoz, M.C.; Bartual-Murgui, C.; Real, J.A. Bistable Hofmann-Type FeII Spin-Crossover Two-Dimensional Polymers of 4-Alkyldisulfanylpyridine for Prospective Grafting of Monolayers on Metallic Surfaces. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 9040–9049.

- Seredyuk, M.; Znovjyak, K.; Valverde-Muñoz, F.J.; Da Silva, I.; Muñoz, M.C.; Moroz, Y.S.; Real, J.A. 105 K Wide Room Temperature Spin Transition Memory Due to a Supramolecular Latch Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14297–14309.

- Hiiuk, V.M.; Shova, S.; Rotaru, A.; Ksenofontov, V.; Fritsky, I.O.; Gural’skiy, I.A. Room Temperature Hysteretic Spin Crossover in a New Cyanoheterometallic Framework. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 3359–3362.

- Zhao, X.H.; Shao, D.; Chen, J.T.; Gan, D.X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.Z. A Trinuclear Complex Involving Both Spin and Non-Spin Transitions Exhibits Three-Step and Wide Thermal Hysteresis. Sci. China Chem. 2022, 65, 532–538.

- Kumar, B.; Paul, A.; Mondal, D.J.; Paliwal, P.; Konar, S. Spin-State Modulation in FeII-Based Hofmann-Type Coordination Polymers: From Molecules to Materials. Chem. Rec. 2022, 22, e202200135.

- You, M.; Shao, D.; Deng, Y.F.; Yang, J.; Yao, N.T.; Meng, Y.S.; Ungur, L.; Zhang, Y.Z. -Armed Square Complex Showing Unusual Spin-Crossover Behavior Due to a Symmetry-Breaking Phase Transition. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 5855–5860.

- Amin, N.; Said, S.; Salleh, M.; Afifi, A.; Ibrahim, N.; Hasnan, M.; Tahir, M.; Hashim, N. Review of Fe-Based Spin Crossover Metal Complexes in Multiscale Device Architectures. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2023, 544, 121168.

- Halcrow, M.A. Structure: Function Relationships in Molecular Spin-Crossover Complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4119–4142.

- Halcrow, M.A. The Foundation of Modern Spin-Crossover. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 10890–10892.

- Pavlik, J.; Boča, R. Established Static Models of Spin Crossover. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 2013, 697–709.

- Feng, M.; Ruan, Z.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Tong, M.L. Physical Stimulus and Chemical Modulations of Bistable Molecular Magnetic Materials. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 13702–13718.

- Real, J.A.; Gaspar, A.B.; Niel, V.; Muñoz, M.C. Communication between Iron(II) Building Blocks in Cooperative Spin Transition Phenomena. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003, 236, 121–141.

- Kumar, K.S.; Ruben, M. Emerging Trends in Spin Crossover (SCO) Based Functional Materials and Devices. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 346, 176–205.

- Ren, D.H.; Qiu, D.; Pang, C.Y.; Li, Z.; Gu, Z.G. Chiral Tetrahedral Iron(II) Cages: Diastereoselective Subcomponent Self-Assembly, Structure Interconversion and Spin-Crossover Properties. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 788–791.

- Hogue, R.W.; Singh, S.; Brooker, S. Spin Crossover in Discrete Polynuclear Iron(II) Complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7303–7338.

- Létard, J.-F.; Guionneau, P.; Goux-Capes, L. Towards Spin Crossover Applications. Spin Crossover Transit. Met. Compd. III 2006, 1, 221–249.

- Murray, K.S. Advances in Polynuclear Iron(II), Iron(III) and Cobalt(II) Spin-Crossover Compounds. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 2008, 3101–3121.

- Cavallini, M.; Melucci, M. Organic Materials for Time-Temperature Integrator Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 16897–16906.

- Mallah, T.; Cavallini, M. Surfaces, Thin Films and Patterning of Spin Crossover Compounds. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2018, 21, 1270–1286.

- Hiiuk, V.M.; Shova, S.; Rotaru, A.; Golub, A.A.; Fritsky, I.O.; Gural’Skiy, I.A. Spin Crossover in 2D Iron(II) Phthalazine Cyanometallic Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 5302–5311.

- Pittala, N.; Cuza, E.; Pinkowicz, D.; Magott, M.; Marchivie, M.; Boukheddaden, K.; Triki, S. Antagonist Elastic Interactions Tuning Spin Crossover and LIESST Behaviours in FeII Trinuclear-Based One-Dimensional Chains. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 6468–6481.

- Kulmaczewski, R.; Cook, L.J.K.; Pask, C.M.; Cespedes, O.; Halcrow, M.A. Iron(II) Complexes of 4-(Alkyldisulfanyl)-2,6-Di(Pyrazolyl)Pyridine Derivatives. Correlation of Spin-Crossover Cooperativity with Molecular Structure Following Single-Crystal-to-Single-Crystal Desolvation. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 1960–1971.

- Fujita, K.; Kawamoto, R.; Tsubouchi, R.; Sunatsuki, Y.; Kojima, M.; Iijima, S.; Matsumoto, N. Spin States of Mono- and Dinuclear Iron(II) Complexes with Bis(Imidazolylimine) Ligands. Chem. Lett. 2007, 36, 1284–1285.

- Hagiwara, H.; Tanaka, T.; Hora, S. Synthesis, Structure, and Spin Crossover above Room Temperature of a Mononuclear and Related Dinuclear Double Helicate Iron(II) Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 17132–17140.

- Sunatsuki, Y.; Kawamoto, R.; Fujita, K.; Maruyama, H.; Suzuki, T.; Ishida, H.; Kojima, M.; Iijima, S.; Matsumoto, N. Structures and Spin States of Bist (Tridentate)-Type Mononuclear and Triple Helicate Dinuclear Iron(II) Complexes of Lmidazole-4-Carbaldehyde Azine. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 8784–8795.

- Sunatsuki, Y.; Kawamoto, R.; Fujita, K.; Maruyama, H.; Suzuki, T.; Ishida, H.; Kojima, M.; Iijima, S.; Matsumoto, N. Structures and Spin States of Mono- and Dinuclear Iron(II) Complexes of Imidazole-4-Carbaldehyde Azine and Its Derivatives. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 1871–1881.

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Thierer, L.M.; Weberg, A.B.; Gau, M.R.; Carroll, P.J.; Tomson, N.C. Tuning Metal-Metal Interactions through Reversible Ligand Folding in a Series of Dinuclear Iron Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 12234–12244.

- Nabei, A.; Kuroda-Sowa, T.; Shimizu, T.; Okubo, T.; Maekawa, M.; Munakata, M. Ferromagnetic Interaction in Iron(II)-Bis-Schiff Base Complexes. Polyhedron 2009, 28, 1734–1739.

- Rezaeivala, M.; Keypour, H. Schiff Base and Non-Schiff Base Macrocyclic Ligands and Complexes Incorporating the Pyridine Moiety—The First 50 Years. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 280, 203–253.

- Powers, T.M.; Betley, T.A. Testing the Polynuclear Hypothesis: Multielectron Reduction of Small Molecules by Triiron Reaction Sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12289–12296.

- Powers, T.M.; Fout, A.R.; Zheng, S.L.; Betley, T.A. Oxidative Group Transfer to a Triiron Complex to Form a Nucleophilic μ(3)-Nitride, -. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 3336–3338.

- Bartholomew, A.K.; Juda, C.E.; Nessralla, J.N.; Lin, B.; Wang, S.Y.G.; Chen, Y.S.; Betley, T.A. Ligand-Based Control of Single-Site vs. Multi-Site Reactivity by a Trichromium Cluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5687–5691.

- Struch, N.; Brandenburg, J.G.; Schnakenburg, G.; Wagner, N.; Beck, J.; Grimme, S.; Lützen, A. A Case Study of Mechanical Strain in Supramolecular Complexes to Manipulate the Spin State of Iron(II) Centres. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 2015, 5503–5510.

- Han, W.K.; Li, Z.H.; Zhu, W.; Li, T.; Li, Z.; Ren, X.; Gu, Z.G. Molecular Isomerism Induced Fe(II) Spin State Difference Based on the Tautomerization of the 4(5)-Methylimidazole Group. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 4218–4224.

- Seredyuk, M.; Muñoz, M.C.; Castro, M.; Romero-Morcillo, T.; Gaspar, A.B.; Real, J.A. Unprecedented Multi-Stable Spin Crossover Molecular Material with Two Thermal Memory Channels. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 6591–6596.

- Tuna, F.; Lees, M.R.; Clarkson, G.J.; Hannon, M.J. Readily Prepared Metallo-Supramolecular Triple Helicates Designed to Exhibit Spin-Crossover Behaviour. Chem. Eur. J. 2004, 10, 5737–5750.

- Pelleteret, D.; Clérac, R.; Mathonière, C.; Harté, E.; Schmitt, W.; Kruger, P.E. Asymmetric Spin Crossover Behaviour and Evidence of Light-Induced Excited Spin State Trapping in a Dinuclear Iron(II) Helicate. Chem. Commun. 2009, 221–223.

- Tanaka, T.; Sunatsuki, Y.; Suzuki, T. Iron(II) Complexes Having Dinuclear Mesocate or Octanuclear Bicapped Trigonal Prism Structures Dependent on the Rigidity of Bis(Bidentate) Schiff Base Ligands Containing Imidazole Groups. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 93, 427–437.

- Harding, L.P.; Jeffery, J.C.; Riis-Johannessen, T.; Rice, C.R.; Zeng, Z. Anion Control of the Formation of Geometric Isomers in a Triple Helical Array. Dalton Trans. 2004, 44, 2396–2397.

- Garcia, Y.; Robert, F.; Naik, A.D.; Zhou, G.; Tinant, B.; Robeyns, K.; Michotte, S.; Piraux, L. Spin Transition Charted in a Fluorophore-Tagged Thermochromic Dinuclear Iron(II) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 15850–15853.

- Scott, H.S.; Ross, T.M.; Moubaraki, B.; Murray, K.S.; Neville, S.M. Spin Crossover in Polymeric Materials Using Schiff Base Functionalized Triazole Ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 2013, 803–812.

- Roubeau, O.; Gamez, P.; Teat, S.J. Dinuclear Complexes with a Triple N1,N2-Triazole Bridge That Exhibit Partial Spin Crossover and Weak Antiferromagnetic Interactions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 2013, 934–942.

- Cheng, X.; Yang, Q.; Gao, C.; Wang, B.W.; Shiga, T.; Oshio, H.; Wang, Z.M.; Gao, S. Thermal and Light Induced Spin Crossover Behavior of a Dinuclear Fe(II) Compound. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 11282–11285.

- Wu, D.Q.; Shao, D.; Wei, X.Q.; Shen, F.X.; Shi, L.; Kempe, D.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Dunbar, K.R.; Wang, X.Y. Reversible On-Off Switching of a Single-Molecule Magnet via a Crystal-to-Crystal Chemical Transformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 11714–11717.

- Kolnaar, J.J.A.; de Heer, M.I.; Kooijman, H.; Spek, A.L.; Schmitt, G.; Ksenofontov, V.; Gütlich, P.; Haasnoot, J.G.; Reedijk, J. Synthesis, Structure and Properties of a Mixed Mononuclear/Dinuclear Iron(II) Spin-Crossover Compound with the Ligand 4-(p-Tolyl)-1,2,4-Triazole. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 1999, 881–886.

- McConnell, A.J. Spin-State Switching in Fe(II) Helicates and Cages. Supramol. Chem. 2018, 30, 858–868.

- Darawsheh, M.; Barrios, L.A.; Roubeau, O.; Teat, S.J.; Aromí, G. Guest-, Light- and Thermally-Modulated Spin Crossover in Supramolecular Helicates. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 8635–8645.

- Clements, J.E.; Airey, P.R.; Ragon, F.; Shang, V.; Kepert, C.J.; Neville, S.M. Guest-Adaptable Spin Crossover Properties in a Dinuclear Species Underpinned by Supramolecular Interactions. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 14930–14938.

More