You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jason Zhu and Version 1 by Benedetta Fibbi.

Nowadays, iIt is well accepted that the central nervous system is not the only target of low [Na+]. Indeed, mild chronic hyponatremia has also been associated with detrimental effects on bone, specifically increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures independently of bone demineralization.

- Oxidative Stress

- hyponatremia

- Non Osmotically-Induced

1. Introduction

Bone matrix is a large reservoir of the body’s Na+, storing approximately one-third of this electrolyte [105][1]; in dogs, it is an osmotically inactive compartment from which Na+ is released during prolonged dietary deprivation [106][2]. As demonstrated in a rat model of SIAD, hyponatremia-related osteoporosis is due to increased osteoclastic activity, in the absence of other metabolic or hormonal alterations able to explain the accelerated bone resorption (i.e., sex steroid deficiency, metastasis-induced osteolysis, calcium-mediated signals, etc.) [36][3].

2. Non Osmotically-Induced Oxidative Stress

The described detrimental systemic effects secondary to chronic hyponatremia, traditionally defined as an asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic disorder, open a new scenario in understanding the pathophysiology of this condition and its clinical sequelae. In fact, neurological and extra-neurological alterations observed in chronic hyponatremia are explained in principle neither by the “osmotic theory” nor by the homeostatic mechanisms that counteract cell swelling in the presence of extracellular hypotonicity. Therefore, the intriguing hypothesis that hyponatremia could directly impair cellular homeostasis—and hence health status—was postulated. With regard to this point, Barsony et al. first showed that sustained low extracellular [Na+] activates osteoclastogenesis and osteoclastic bone matrix resorption in rats both in vivo and in vitro, independently of reduced osmolality [104][4]. In their view, this response is likely necessary to mobilize bone-stored Na+ in the attempt to restore normal extracellular [Na+]. Moreover, low [Na+] is able to stimulate the differentiation of early-stage osteoclast progenitors compared to normonatremic conditions, by increasing their sensitivity to growth factors (in particular M-CSF) through oxidative stress. These findings suggest the existence of a Na+-sensing mechanism or receptor on osteoclasts, as hypothesized also in the central nervous system and in the kidney. Interestingly, the authors found that the activity of the Na+-dependent vitamin C transporter is inhibited by low extracellular [Na+] in a dose-dependent manner, thus resulting in a reduced uptake of ascorbic acid. As well as playing a central role in setting the equilibrium between osteoclastogenenesis and osteoblastic functions, ascorbic acid is also a key scavenger of oxidative stress [107,108][5][6]. As expected, reduced ascorbic acid uptake observed in the above-mentioned model of chronic hyponatremia is associated with increased accumulation of ROS in osteoclastic cells and oxidative DNA damage product 8-OHdg in the sera of hyponatremic rats compared to controls, in agreement with the excessive production of free radicals and osteoclastic bone reabsorption observed in other forms of osteoporosis (e.g., estrogen/androgen deficiency and chronic inflammation) [104][4]. By developing an in vitro model able to mimic chronic hyponatremia, wresearchers further assessed the correlation between hyponatremia and bone health and analyzed the second process involved in bone remodeling alongside resorption, namely neoformation of bone matrix. Weresearchers showed that reduced extracellular [Na+] disrupts gene expression, proliferation, migration, and cytokine production in human mesenchymal stromal cells (hMSC) [109][7], which are precursors of mesodermal cell types (including adipocytes and osteoblasts of bone matrix) exhibiting different degrees of stemness [110][8]. In post-menopausal osteoporosis and other conditions characterized by bone loss, the bone marrow shows an imbalance between adipogenesis and osteogenesis, with an accumulation of adipose tissue at the expense of the osteoblastic compartment [111][9]. In our in vitro model, low [Na+] impairs osteoblast activity and differentiation of hMSC, which are shifted toward the adipogenic phenotype at the expense of the osteogenic one [109][7].

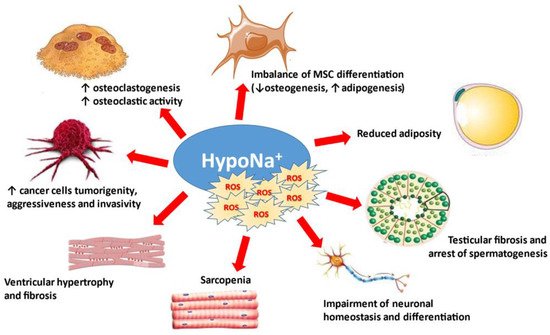

Oxidative stress is also a well-recognized mediator of degenerative processes related to senescence, other than osteoporosis [112][10], especially in the brain [113][11]. It is then not inconceivable to speculate that chronic hyponatremia might play a direct role in the pathogenesis of degenerative diseases, in particular aging-related multi-organ pathologies, and that its combination with comorbidities in old people might critically weaken the defense against oxidative stress. As a consequence, sustained low [Na+] might accelerate the aging process and represent an independent risk factor for the development and progression of age-related infirmities. In fact, the prevalence of hyponatremia increases progressively with aging, and its major impact (in terms of morbidity and mortality) is exerted in the elderly [114][12]. The link between chronic hyponatremia and senescence is supported by evidence that chronic hyponatremia (also in this case regardless of hypoosmolality) accelerates and exacerbates multiple manifestations of senescence, including osteoporosis, hypogonadism with testicular fibrosis and arrest of spermatogenesis, reduced adiposity, cardiomyopathy with left ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis, and sarcopenia, in male rats [115][13]. Consistently with these data, primary cultures of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes exposed to low extracellular [Na+] (but compensated hypoosmolality) and hearts isolated from hyponatremic animals showed increased ROS production and intracellular Ca2+ concentrations compared to control cells and tissues [116][14]. This results in a greater vulnerability of cells against oxidative stress and an exacerbation of myocardial injury due to ischemia/reperfusion, as evidenced by significantly larger infarct size and lower left ventricular developed pressure after exposure to global hypoxia in rats with hyponatremia compared to normonatremic ones [116][14]. Reoxygenation of cells triggers a burst of ROS, and their increment in low Na+ conditions may amplify mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening and induce cell death [117][15]. Swelling and enlargement of mitochondria and destruction of cristae in cardiomyocytes exposed to low [Na+] might be the result of increased ROS content, which in turn could be secondary to intracellular Ca2+ overload and activation of Ca2+-dependent ROS-generating enzymes [118][16].

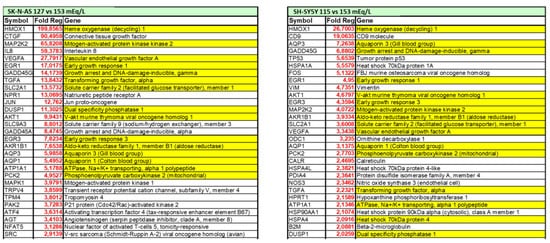

Understanding the potential direct effects of low extracellular [Na+] is of particular interest also in the brain, which is one of the main targets of both chronic hyponatremia and senescence. In the last decade, ourthe laboratory demonstrated that low extracellular [Na+] directly impairs cellular homeostasis in an in vitro neuronal model of chronic hyponatremia [119][17]. Sustained low extracellular [Na+] was demonstrated to induce cell distress by affecting cell viability and adhesion, expression of anti-apoptotic genes (Bcl-2, DHCR24) and ability to differentiate into a mature neuronal phenotype, even in the presence of compensated osmolality. As a result of a comprehensive microarray analysis, wresearchers showed that cell functions involved in “cell death and survival” are the most altered in the presence of reduced [Na+] compared to controls, and that the expression of the heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX-1) gene is the most increased [119][17] (Figure 21).

Figure 21. List of differentially expressed genes in two in vitro neuronal models (SH-SY5Y and SKN-AS cell lines), maintained at reduced (115 mmol/L and 127 mmol/L, respectively) or normal (153 mmol/L) [Na+], as assessed by microarray analysis. Positive fold-regulations are reported in red, negative fold-regulations are in blue. Yellow marked genes are commonly regulated in both cell lines.

HMOX-1 is an inducible stress protein with a metabolic function in heme turnover [120][18] and potent anti-apoptotic and antioxidant activities in different cells, including neurons [121][19]. In the brain, induction of HMOX-1 by intracellular factors that directly or indirectly generate ROS, preserves neurons from oxidative injury secondary to cerebral ischemia [122][20] or ethanol intoxication [123][21]. Elicitation of oxidative stress in the presence of low [Na+] was confirmed by cytofluorimetric analysis of total intracellular ROS and ROS-induced lipid peroxidation [124][22]. These findings reinforce the hypothesis that chronic hyponatremia, through increased oxidative stress and ROS generation, may have a role in brain distress and aging by reducing neuronal differentiation ability, a well-known co-factor in the etiopathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease [125][23]. Finally, wresearchers also demonstrated that the correction of sustained low extracellular [Na+] may not be able to revert all the cell alterations associated with reduced [Na+], specifically the expression level of the anti-apoptotic genes Bcl-2 and DHCR24 or of the HMOX-1 gene, even when [Na+] was gradually increased [124][22]. Admittedly, these data appear to reinforce the recommendation to carefully diagnose and treat patients with hyponatremia because a prompt intervention aimed to correct serum [Na+] might prevent possible residual abnormalities.

It is now widely accepted that hyponatremia represents a negative independent prognostic factor in oncologic patients, and is associated with poor progression-free and overall survival in several cancers [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33]. The direct contribution of this electrolyte imbalance (which cannot be considered a mere surrogate marker of the severity of clinical conditions) is supported by the observation that the correction of serum [Na+] may reduce the overall mortality rate in hyponatremic patients [37][34]. Wresearchers recently demonstrated, for the first time, that the reduction of extracellular [Na+] is able to alter the homeostasis of different human cancer cell lines, thus affecting cell functions (i.e., proliferation, adhesion and invasion) distinctive of a more malignant behavior able to increase cell tumorigenicity [126][35]. The three steps of carcinogenesis (initiation, promotion, and progression) and the resistance to treatment are strongly impaired by an imbalance between ROS and antioxidant production [127,128][36][37]. In fact, oxidative stress regulates cell growth, cytoskeleton remodeling and migration, excitability, exocytosis and endocytosis, autophagy, hormone signaling, necrosis, and apoptosis, namely cell properties deregulated in cancer [127,129][36][38]. Furthermore, ROS involvement in carcinogenesis, local invasiveness and metastatization is displayed by their ability to induce genomic instability and/or transcriptional errors [130][39], and to activate pro-survival and pro-metastatic pathways [129][38]. OurThe demonstration of an increased expression of HMOX-1 in cancer cell lines cultured in low extracellular [Na+], compared to normal Na+ conditions, validates the role of oxidative stress as the molecular basis of hyponatremia-associated poorer outcomes in oncologic patients [126][35]. Cancer cells have great abilities to adapt to perturbation of cellular homeostasis, including the imbalanced redox status secondary to their high metabolism and local hypoxia. Through a fine regulation of both ROS production and ROS scavenging pathways (the theory of ROS rheostat), they show a high antioxidant capacity, allowing oxidative stress levels compatible with cellular functions even if higher than in normal cells [131][40]. Recent studies reported an increased expression of ROS scavengers and low ROS levels in liver and breast cancer stem cells [132[41][42],133], whose maintenance is crucial for the survival of pre-neoplastic foci. In this view, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, which strongly induce ROS synthesis, are often able to eliminate the bulk of cancer cells but not to definitely cure cancer, because of the up-regulated levels of antioxidants in stem cells, which are thus spared and selected for in the presence of high ROS. An additional mechanism responsible for therapeutic failure is ROS-dependent accumulation of DNA mutations, leading to drug resistance [131][40]. In this very complex scenario, antioxidant inhibitors are considered a promising therapeutic tool in cancer treatment, especially regarding glutathione metabolism. Since glutathione is a key regulator of the redox balance and protects cancer cells from stress due to hypoxia and nutrient deficiency in solid tumors, the combination of glutathione inhibitors with radiotherapy or chemotherapy could improve the effects of radiation or drugs. However, other enzymes with a scavenging effect on oxidative stress (HSP90, thioredoxin, enzyme poly-ADP-ribose polymerase or PARP) may be targeted for anticancer treatments, and are currently under study [131][40]. Since cancer-related hyponatremia adversely affects the response to chemotherapy and everolimus in metastatic renal cell carcinoma [61[31][43],134], correction of low serum [Na+] may exert its role in improving cancer survival [135,136][44][45] by regulating cancer cell ROS rheostat.

The direct effects of reduced extracellular [Na+] on cells and tissues are summarized in Figure 32.

Figure 32.

Osmotically-independent effects of hyponatremia and oxidative stress. MSC: mesenchymal stromal cells.

References

- Bergstrom, W.H.; Wallace, W.M. Bone as a sodium and potassium reservoir. J. Clin. Investig. 1954, 33, 867–873.

- Seeliger, E.; Ladwig, M.; Reinhardt, H.W. Are large amounts of sodium stored in an osmotically inactive form during sodium retention? Balance studies in freely moving dogs. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006, 290, R1429–R1435.

- Verbalis, J.G.; Barsony, J.; Sugimura, Y.; Tian, Y.; Adams, D.J.; Carter, E.A.; Resnick, H.E. Hyponatremia-induced osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 554–563.

- Barsony, J.; Sugimura, Y.; Verbalis, J.G. Osteoclast response to low extracellular sodium and the mechanism of hyponatremia-induced bone loss. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 10864–10875.

- Wu, X.; Itoh, N.; Taniguchi, T.; Nakanishi, T.; Tatsu, Y.; Yumoto, N.; Tanaka, K. Zinc-induced sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2 expression: Potent roles in osteoblast differentiation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003, 420, 114–120.

- Xiao, X.H.; Liao, E.Y.; Zhou, H.D.; Dai, R.C.; Yuan, L.Q.; Wu, X.P. Ascorbic acid inhibits osteoclastogenesis of RAW264.7 cells induced by receptor activated nuclear factor kappaB ligand (RANKL) in vitro. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2005, 28, 253–260.

- Fibbi, B.; Benvenuti, S.; Giuliani, C.; Deledda, C.; Luciani, P.; Monici, M.; Mazzanti, B.; Ballerini, C.; Peri, A. Low extracellular sodium promotes adipogenic commitment of human mesenchymal stromal cells: A novel mechanism for chronic hyponatremia-induced bone loss. Endocrine 2016, 52, 73–85.

- Baksh, D.; Song, L.; Tuan, R.S. Adult mesenchymal stem cells: Characterization, differentiation, and application in cell and gene therapy. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2004, 8, 301–316.

- Rosen, C.J.; Ackert-Bicknell, C.; Rodriguez, J.P.; Pino, A.M. Marrow fat and the bone microenvironment: Developmental, functional and pathological implications. Crit. Rev. Eukariot. Gene Expr. 2009, 19, 109–124.

- Sohal, R.S.; Weindruch, R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science 1996, 273, 59–63.

- Yakner, B.A.; Lu, T.; Loerch, P. The Aging Brain. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008, 3, 41–66.

- Upadhyay, A.; Jaber, B.L.; Madias, N.E. Incidence and prevalence of hyponatremia. Am. J. Med. 2006, 119, S30–S35.

- Barsony, J.; Manigrasso, M.B.; Xu, Q.; Tam, H.; Verbalis, J.G. Chronic hyponatremia exacerbates multiple manifestations of senescence in male rats. Age 2013, 35, 271–288.

- Oniki, T.; Teshima, Y.; Nishio, S.; Ishii, Y.; Kira, S.; Abe, I.; Yufu, K.; Takahashi, N. Hyponatremia aggravates cardiac susceptibility to ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int. J. Exp. Path. 2019, 100, 350–358.

- Crompton, M. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem. J. 1999, 341, 233–249.

- Goordeva, A.V.; Zvyagilskaya, R.A.; Labas, Y.A. Cross-talk between reactive oxygen species and calcium in living cells. Biochemistry 2003, 68:1077-1080; Brookes PS. Mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. Mitochondrion 2004, 3, 187–204.

- Benvenuti, S.; Deledda, C.; Luciani, P.; Modi, G.; Bossio, A.; Giuliani, C.; Fibbi, B.; Peri, A. Low extracellular sodium causes neuronal distress independently of reduced osmolality in an experimental model of chronic hyponatremia. Neuromol. Med. 2013, 15, 493–503.

- Mancuso, C. Heme oxygenase and its products in the nervous system. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2004, 6, 878–887.

- Chen, K.; Gunter, K.; Maines, M.D. Neurons overexpressing heme oxygenase-1 resist oxidative stress-mediated cell death. J. Neurochem. 2000, 75, 304–313.

- Takizawa, S.; Hirabayashi, H.; Matsushima, K.; Tokuoka, K.; Shinohara, Y. Induction of heme oxygenase protein protects neurons in cortex and striatum, but not in hippocampus, against transient forebrain ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1998, 18, 559–569.

- Ku, B.M.; Joo, Y.; Mun, J.; Roh, G.S.; Kang, S.S.; Cho, G.J. Heme oxygenase protects hippocampal neurons from ethanol-induced neurotoxicity. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 405, 168–171.

- Benvenuti, S.; Deledda, C.; Luciani, P.; Giuliani, C.; Fibbi, B.; Muratori, M.; Peri, A. Neuronal distress induced by low extracellular sodium in vitro is partially reverted by the return to normal sodium. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2016, 39, 177–184.

- Shruster, A.; Melamed, E.; Offen, D. Neurogenesis in the aged and neurodegenerative brain. Apoptosis 2010, 15, 1415–1421.

- Dhaliwal, H.S.; Rohatiner, A.Z.; Gregory, W.; Richards, M.A.; Johnson, P.W.; Whelan, J.S.; Gallagher, C.J.; Matthews, J.; Ganesan, T.S.; Barnett, M.J. Combination chemotherapy for intermediate and high grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Br. J. Cancer 1993, 68, 767–774.

- Zhou, M.H.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhou, H.W.; Liu, M.; Gu, Y.J.; Sun, J.Z. Clinical outcome of 30 patients with bone marrow metastases. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2018, 14, S512–S515.

- Choi, J.S.; Bae, E.H.; Ma, S.K.; Kweon, S.S.; Kim, S.W. Prognostic impact of hyponatraemia in patients with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2015, 17, 409–416.

- Gines, P.; Guevara, M. Hyponatremia in cirrhosis: Pathogenesis, clinical significance, and management. Hepatology 2008, 48, 1002–1010.

- Cescon, M.; Cucchetti, A.; Grazi, G.L.; Ferrero, A.; Viganò, L.; Ercolani, G.; Zanello, M.; Ravaioli, M.; Capussotti, L.; Pinna, A.D. Indication of the extent of hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis by a simple algorithm based on preoperative variables. Arch. Surg. 2009, 144, 57–63.

- Berardi, R.; Caramanti, M.; Fiordoliva, I.; Morgese, F.; Savini, A.; Rinaldi, S.; Torniai, M.; Tiberi, M.; Ferrini, C.; Castagnani, M.; et al. Hyponatraemia is a predictor of clinical outcome for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Support Care Cancer 2015, 23, 621–626.

- Vasudev, N.S.; Brown, J.E.; Brown, S.R.; Rafiq, R.; Morgan, R.; Patel, P.M.; O’Donnell, D.; Harnden, P.; Rogers, M.; Cocks, K.; et al. Prognostic factors in renal cell carcinoma: Association of preoperative sodium concentration with survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 1775–1781.

- Schutz, F.A.; Xie, W.; Donskov, F.; Sircar, M.; McDermott, D.F.; Rini, B.I.; Agarwal, N.; Pal, S.K.; Srinivas, S.; Kollmannsberger, C.; et al. The impact of low serum sodium on treatment outcome of targeted therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer Database Consortium. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 723–730.

- Gandhi, L.; Johnson, B.E. Paraneoplastic syndromes associated with small cell lung cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2006, 4, 631–638.

- Rawson, N.S.; Peto, J. An overview of prognostic factors in small cell lung cancer. A report from the Subcommittee for the Management of Lung Cancer of the United Kingdom Coordinating Committee on Cancer Research. Br. J. Cancer 1990, 61, 597–604.

- Corona, G.; Giuliani, C.; Verbalis, J.G.; Forti, G.; Maggi, M.; Peri, A. Hyponatremia improvement is associated with a reduced risk of mortality: Evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124105.

- Marroncini, G.; Fibbi, B.; Errico, A.; Grappone, C.; Maggi, M.; Peri, A. Effects of low extracellular sodium on proliferation and invasive activity of cancer cells in vitro. Endocrine 2020, 67, 473–484.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Panieri, E.; Santoro, M.M. ROS homeostasis and metabolism: A dangerous liason in cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2253.

- Zelenka, J.; Koncosova, M.; Ruml, T. Targeting of stress response pathways in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 583–602.

- Marnett, L.J. Oxyradicals and DNA damage. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 361–370.

- Gorrini, C.; Harris, I.S.; Mak, T.W. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 931–947.

- Diehn, M.; Cho, R.W.; Lobo, N.A.; Kalisky, T.; Dorie, M.J.; Kulp, A.N.; Qian, D.; Lam, J.S.; Ailles, L.E.; Wong, M.; et al. Association of reactive oxygen species levels and radioresistance in cancer stem cells. Nature 2009, 458, 780–783.

- Kim, H.M.; Haraguchi, N.; Ishii, H.; Ohkuma, M.; Okano, M.; Mimori, K.; Eguchi, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Nagano, H.; Sekimoto, M.; et al. Increased CD13 expression reduces reactive oxygen species, promoting survival of liver cancer stem cells via an epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like phenomenon. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 539–548.

- Jeppesen, A.N.; Jensen, H.K.; Donskov, F.; Marcussen, N.; von der Maase, H. Hyponatremia as a prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 867–872.

- Penttila, P.; Bono, P.; Peltola, K.; Donskov, F. Hyponatremia associates with poor outcome in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with everolimus: Prognostic impact. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 1580–1585.

- Berardi, R.; Santoni, M.; Newsom-Davis, T.; Caramanti, M.; Rinaldi, S.; Tiberi, M.; Morgese, F.; Torniai, M.; Pistelli, M.; Onofri, A.; et al. Hyponatremia normalization as an independent prognostic factor in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with first-line therapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 23871–23879.

More