You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Aleksandra Nowysz.

Urban agriculture (UA) has become a commonly discussed topic in recent years with respect to sustainable development. Therefore, the combination of urban fabric and local food production is crucial for ecological reasons. The key issues are the reduction of food miles and the demand for processed food, the production of which strains the natural environment.

- urban agriculture

- urban farm

- community garden

- allotment garden

- circular economy

1. Introduction

Since the 1990s, sustainable urban development has been implemented worldwide in response to a range of problems, such as urban sprawl, pollution, traffic congestion, economic decline in developed countries, and rapid urbanization in developing countries [1].The concept of sustainability has been widely discussed by various disciplines over the last and current century [1,2,3,4,5,6][1][2][3][4][5][6]. This criticism has led to the search for even more progressive ways of thinking about urban “development,” which are defined by notions such as circular economy (CE) [14[7][8][9][10][11],15,16,17,18], urban resilience [19[12][13][14],20,21], urban metabolism (UM) [22,23][15][16], nature-based solutions [6,24,25][6][17][18] and ecological renewal [26][19], but also degrowth (Oslo Architectur Triennale, 2019). These concepts point to the formation of a regenerative city paradigm that goes far beyond a sustainable one. Therefore, it might be more useful in the context of the current crises: environmental, social, and economic.

The CE concept aims to eliminate the waste of materials by bringing them back into second use. Looping natural resources in the life cycle reduces the need to extract natural resources. The main goal of CE is the harmonious development of humanity and the introduction of sustainability elements into the economy without adverse impact on the existing ecosystem [27,28][20][21]. CE is sustainable but also regenerative, considering composting of organic waste and soil production. Therefore, it is important to implement CE in urban green areas.

An inherent value of open green spaces in an urban environment is, among others, urban ventilation, reducing temperatures (alleviate heat island problems), absorbing carbon dioxide, releasing oxygen, water retention, and enhancing biodiversity [29,30,31,32][22][23][24][25]. In addition to urban greenery (green infrastructure), water plays a key ecological and social role in the cities (blue infrastructure). It brings us to the topic of water management, including the issue of water reuse in the context of CE.

2. Allotment Gardens

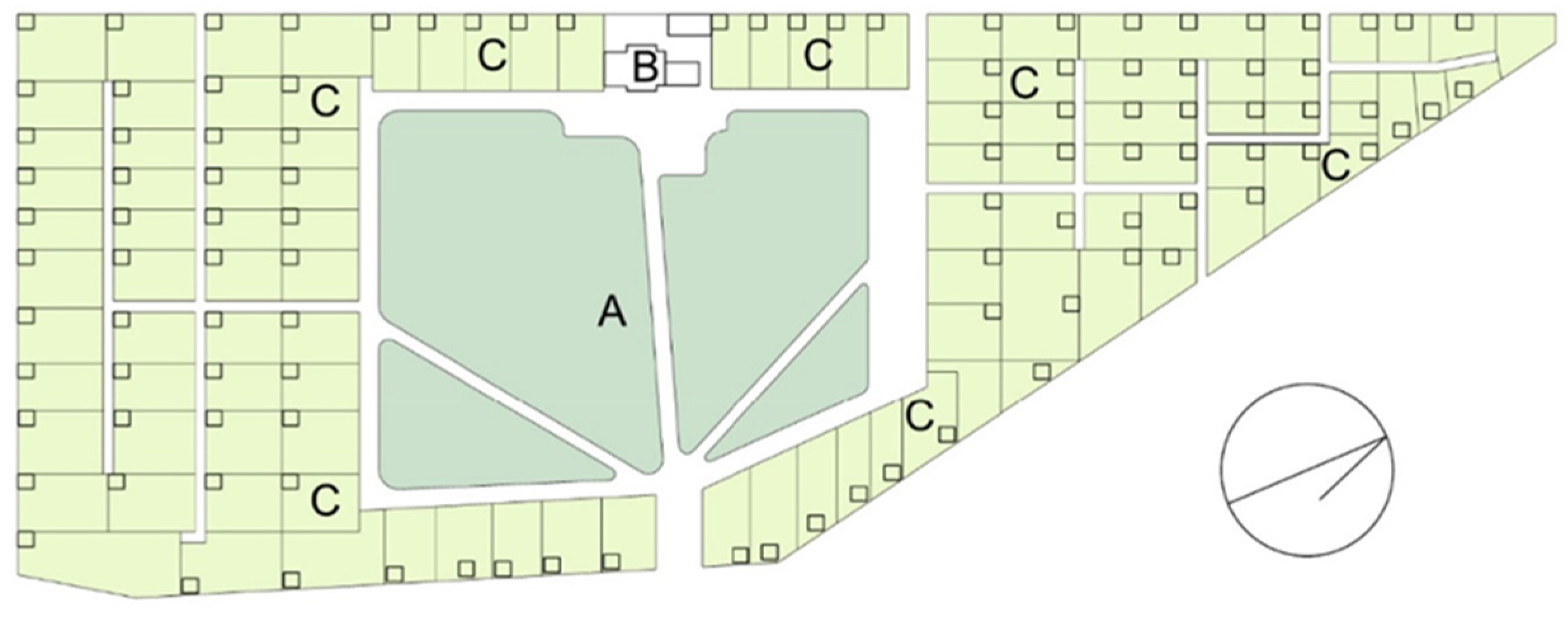

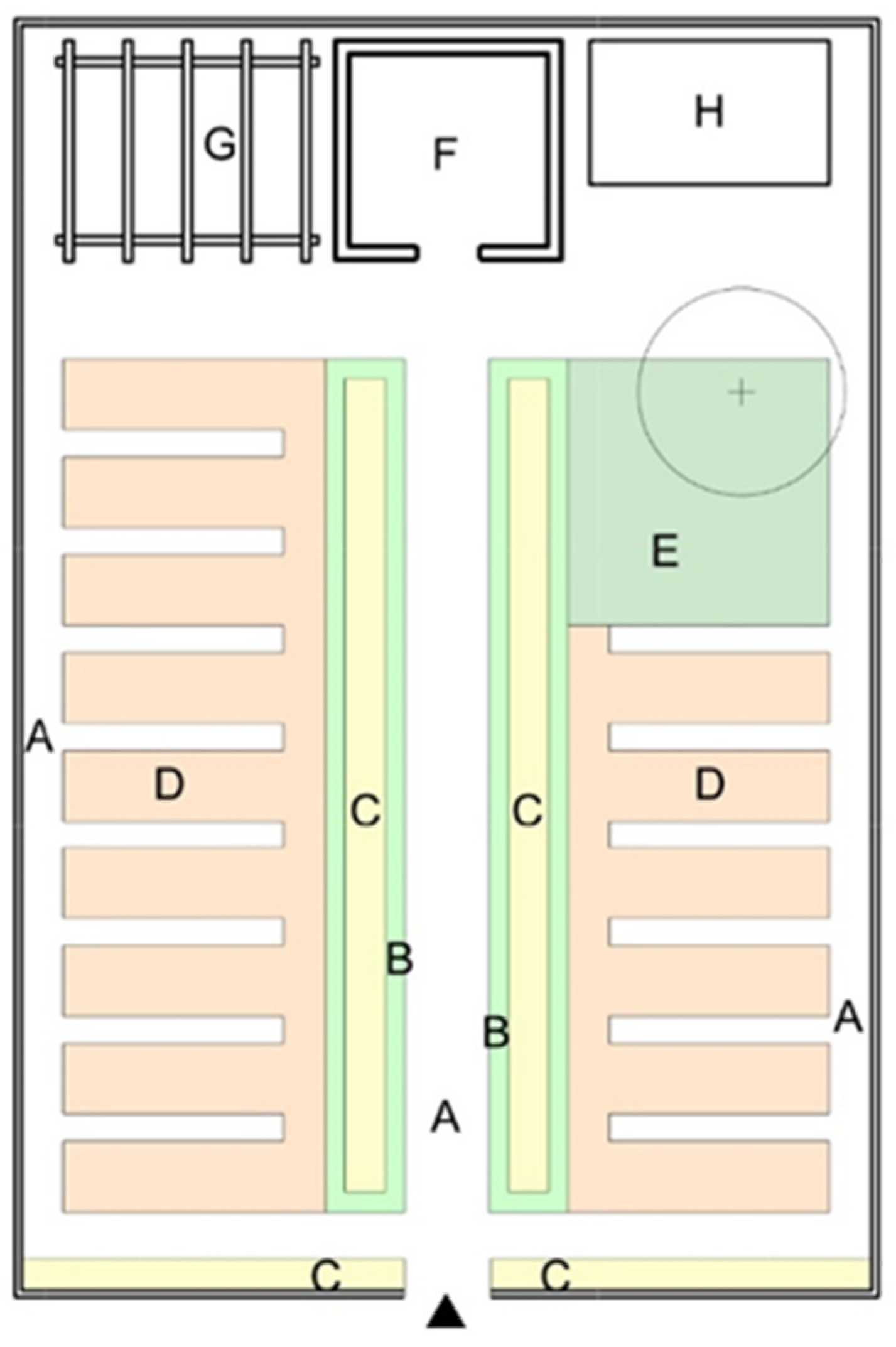

Allotment gardens originated in Europe in the 19th century as a result of the industrial revolution. Industrialization increased the speed of urbanization processes due to the massive inflow of rural populations into cities. In consequence, the UK and Germany were the first countries to encounter the problem of massive internal migration and expansion of poor quarters [49][26] in cities. Due to the large scale of these processes, part of the rural population with knowledge and agricultural experience that could have been used for farming edible plants for their own needs did not find employment in cities. Thus, the first allotment gardens were developed for the unemployed to produce food for their families [50][27]. When analyzing the evolution of allotment gardens, it can be stated that the concept of smallholder space in cities (including allotment gardens), developed in the UK, was later rationalized and included in modernistic design in Germany [49][26]. Allotment gardens were created as individual colonies or as parts of housing estates, near workplaces and schools. The Schrebergärten with a central recreation square belong to the most common allotment establishments in Germany and have been successfully applied also in other countries. A model example of a Schrebergärten is the garden established in 1868 in Leipzig [51][28]. At first, the garden consisted only of a recreation square, because it did not have an agricultural function at that time. The name “Schrebergärten” comes from Mortiz Schreber, who propagated the idea of outdoor educational activities for children and youth in Germany. In turn, Heinrich Gessel, the educator, introduced the concept of surrounding the recreation square with allotment gardens and engaging children in growing plants. Additionally, theatre workshops and handicraft activities, music lessons, hiking, festivals, and lectures on healthy lifestyles and bringing up children were organized in the garden in Leipzig; it became a site for a library, a local newspaper and various social campaigns [52][29] (Figure 1). At present, the garden colony with its entire infrastructure is under protection, being a display of the Museum of German Allotment Gardens (Deutsches Kleingärtnermuseum) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Scheme of the garden colony Schrebergärten in Leipzig (Germany), 1909. A—recreational square, B—allotment board building, C—garden lots, each with a summerhouse (compiled by A. Nowysz, original study, based on local visit).

Figure 2. Scheme of a typical lot in the Schrebergärten garden colony in Leipzig, 1909. A—paths, B—decoration hedge, C—decoration flowers, D—edible plants, E—fruit trees, F—summerhouse, G—terrace with construction for grapevine plants, H—composter (compiled by A. Nowysz, original study, based on local visit).

3. Community Gardens

A community garden represents a local initiative, in which the local community, e.g., neighborhood, is engaged. Community gardens play an important role in urban agriculture and are a valuable resource for urban regeneration [59][32]. The gardens are managed by a group of community members, usually on a cooperative basis and in partnership with city, district, or institutional (e.g., school) authorities [60][33]. They differ from allotment gardens in terms of a smaller total surface area and lack of subdivision into particular rental lots. Community gardens are individual or shared plots of land that are managed and operated by members of the local community with limited access to their land to grow fruit, vegetables, and plants and flowers grown for their attractive appearance [59][32]. Parallel to the development of the allotment movement in Europe, the first community gardens began to be established in North America [61,62,63][34][35][36]. In the United States, already by the end of the nineteenth century vacant lots were made available to residents for food cultivation for their own needs [64][37]. In 1894, the Pingree’s Potato Patches campaign was conducted in Detroit: vacant lots were made available, tools were provided, and the unemployed were engaged in food tillage [62][35]. After the success of this concept, similar campaigns were led in other cities of the United States [65][38], and during the First and Second World Wars, urban gardening, being a food source, became a manifestation of patriotism. Thus, nonresidential areas were used for food production [59,64][32][37]. For example, in 1918 in Chicago, in addition to home gardens covering almost 1500 ha, there were also community gardens on 313 ha and school gardens on 80 ha of the city area [66][39]. These gardens were established on former vacant lots. In turn, after 1945 community gardens started to be eliminated in the United States, and the interest in urban agriculture decreased significantly. The history of community gardens in the form they exist today began with the counterculture of the 1960s. The reintroduction of urban agriculture into public debate took place in the 1970s, along with the idea of self-sufficiency in the context of energy crisis, rising food prices, and shaping of environmental ethics [62,63,67][35][36][40]. From the end of the 20th century, in Western Europe and the United States this gardening movement has become more common, and at present the users of these gardens assemble in various types of unions: local, national, and international [68][41] (Bende & Nagy, 2016). Contemporary communal gardens in the United States usually originate in neglected and vacant lots [67][40]. Created within regular urban housing, they easily become local centers, effectively contributing to the urban renewal of a given district. This revitalization potential is readily used by local authorities. However, the risk of gentrification is also linked to urban renewal as it happened in some cities [69][42]). A good example of the use of urban agriculture is a communal activity organized since 2002 in the United States and known as the National Vacant Properties Campaign [70,71][43][44]), promoting the use of vacant lots in cities. The motto of this campaign is “Creating opportunity from abandonment” (National Vacant Properties Campaign, 2019). The idea was developed, e.g., in Detroit, where numerous community gardens and city farms were established, and in New York, where community gardens are also created near schools. The contemporary nongovernmental organization in the United States, Edible School Yard Project, organizes collective organic gardens in school areas. The beginnings of this initiative reach back to 1995, when a school garden was established in the Martin Luther King School in Berkeley, California. Annually, the organization recruits for an educational program, whose part is the creation of a community garden [72][45]. The Edible School Yard Project is also part of an international platform uniting different institutions working for school gardening: 5510 programs implementing urban agriculture in schools and university have been already registered in its website, among them the interesting Edible School Yard 1 and Edible School Yard 2 solution from New York, designed by the Work Architecture Company (New York, NY, USA) [73][46]. The Edible Schoolyard projects are aimed at gardening education—expanding school programs with practice in gardening and increase of food consciousness among children and youth: gaining knowledge about tillage, ethical food production and a healthy diet. Equally important is ecological education—organic waste is composted in these gardens, to be later used as natural fertilizers, and water use is minimized by its reuse and rainwater capture in retention basins. Moreover, the Edible Schoolyard projects enrich the recreation space around schools with functional and esthetical functions. The forms of new architectural objects (a communal kitchen and green-house) reflect their internal subdivision into function zones. This formal legibility and applied color on the elevations makes the architecture friendly for its most frequent users—children. School gardens are initiatives of a community comprising pupils, their parents and teachers. In turn, in Europe, community gardening is the continuation of allotment gardening [74,75][47][48]. Most modern German community gardens have been established in a bottom-up approach without the influence of professional architects [76][49]. Therefore, their architecture falls into the trend of “anarchitecture,” or contemporary vernacularism. In addition, in many cases these gardens have become well-recognizable urban spaces and often fulfill community activities, such as intercultural integration, decrease of discrimination, and prevention of isolation of national minorities [77][50].In 2014, 80 German institutions signed the manifesto of urban agriculture (Ger. Die Stadt ist unser Garten) to protect the bottom-up creation of community gardens and allotments [78][51].Examples of German community gardens are the Prinzessinnengärten and Allmende-Kontor in Berlin. The Prinzessinnengärten is a garden founded on a vacant lot in a residential quarter of the Kreuzberg district [79,80][52][53]. Due to polluted urban soil [81][54], all plants are cultivated in supplied soil in containers, crates, pots, or other salvage vessels. The garden space is reworked on a current basis, but several permanent elements can be distinguished: the main, central avenue, along which market stands are assembled; restaurant zone: bar, kitchen, tables; plant nursery; tillage zone for different vegetables, fruit and herbs; bee yard; recreation zone with a playground for children; storage houses, facilities, and toilets. “anarchitectural” objects can also be found in the garden, designed and built by community members, e.g., restaurant and kitchen made of industrial containers, exhibition stands and small architecture made of Euro-pallets, and unique summerhouses made of various salvage material [78][51]. The Prinzessinnengärten is an example of a low-budget project of adapting a vacant lot in a residential quarter. As a result, turning a building lot into a tillage lot increases the green area in the dense urban fabric. The space becomes adapted to current requirements. Besides food production, the Prinzessinnengärten is used for social issues, e.g., gardening, food and ecological education, increase of local identity based on work in the local garden, activation and cooperation of various age, cultural, and gender groups, as well as including the residents in the process of urban landscape development. Furthermore, because food production often exceeds self-supply, the garden also gains also significance in an economic aspect, becoming part of the local food system [80][53]. The next example of a community garden is the Allmende-Kontor located in the former Tempelhof Airport in Berlin, transformed in 2010 into a public park [82,83][55][56] 2011, in the eastern part of the former airfield, the Stadtteilgarten Schillerkiez cooperative established the Allmende-Kontor garden. At first a group of 20 people occupied an area of 5000 m2, where 10 garden installations made out of reused material, for example, Euro-pallets, crates, or shopping carts, were assembled and filled with soil for vegetable and fruit tillage [84][57].Further installations were built in the following years and the area of the informal garden gradually expanded. However, some community gardens are created top-down, following an initiative from the city authorities, cultural or educational institutions. In these cases, the organizational institutions (e.g., local school councils) invite selected architects or artists and future users (e.g., settlement residents, pupils) to cooperate in order to develop collective gardens [59][32].This model of establishing a community garden fulfils the idea of social participation in shaping the city, in which the active participation of all parties in the design process, decision making, and project achievement is of key importance. In France, numerous community gardens were developed on the basis of projects prepared by architects or artists cooperating with residents of a given settlement—the future gardeners [85,86][58][59]. The French studio—Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée (AAA)—by applying the social participation strategy, has accomplished several gardens with various groups of Parisian residents. Architects from AAA refer to their projects as self-managed architecture. The main focus of their projects is a more ecological, democratic and bottom-up managed city [87][60].The creation of AAA architects exceeds the material object by linking project studies and urban activism. Most activities of AAA are linked with urban agriculture, e.g., the community gardens Ecobox and Passage 56, and the AgroCité farm. Ecobox is a concept of a mobile community garden, whose location changes depending on the availability of a vacant lot in Paris. The AAA studio has coordinated the establishment of such gardens, e.g., in the La Chapelle district. The first one was created in 2001 on a post-industrial lot near the Halle Pajol complex. The garden had the form of a rectangular platform built of used Euro-pallets in which geometric holes were cut out to serve as patches for plants [88][61].4. Urban Farms

A city farm is a farmland quarter located in the city. Similarly, as in the case of community gardens, farms are established on vacant lots. They differ in their more productive character, i.e., the farm area is maximally used for the tillage of edible plants, whereas recreation–leisure functions do not occur or seldom occur to a much smaller degree. The war-time vegetable gardens established in Europe and the United States during both world wars represent examples of space corresponding to the description of city farms. However, agricultural space in cities began to be known as city farms as late as in the second half of the twentieth century, e.g., a farm created in the outskirts of London in 1972 [92][62] and another established in 1984 in London [93][63]. The basic aim of urban cultivation is supply of fresh fruit and vegetables. Local food production is particularly important in the case of wars or political conflicts or in the case of price speculation for food products. Thus, urban agriculture is one of the elements shaping regional food security [94,95][64][65]. Therefore, in some cities, cultivation areas are introduced top-down, e.g., at national or local government level. In this case, urban agriculture is considered as one of the elements forming the local food system, i.e., organization of food production and distribution, as well as space related with its production, distribution, and consumption [47][66].References

- Lin, S.-H.; Huang, X.; Fu, G.; Chen, J.-T.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.-H.; Tzeng, G.-H. Evaluating the sustainability of urban renewal projects based on a model of hybrid multiple-attribute decision-making. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105570.

- Grimm, N.B.; Faeth, S.H.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Redman, C.L.; Wu, J.; Bai, X.; Briggs, J.M. Global Change and the Ecology of Cities. Science 2008, 319, 756–760.

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422.

- Thomsen, C. Sustainability (World Commission on Environment and Development Definition). In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013.

- Tscharntke, T.; Klein, A.M.; Kruess, A.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Thies, C. Landscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity—Ecosystem service management. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 857–874.

- Xie, L.; Bulkeley, H.; Tozer, L. Mainstreaming sustainable innovation: Unlocking the potential of nature-based solutions for climate change and biodiversity. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 132, 119–130.

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Angrisano, M.; Fusco Girard, L. Circular Economy Strategies in Eight Historic Port Cities: Criteria and Indicators Towards a Circular City Assessment Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3512.

- Knickmeyer, D. Social factors influencing household waste separation: A literature review on good practices to improve the recycling performance of urban areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118605.

- Petrescu, D.; Petcou, C.; Baibarac, C. Co-producing commons-based resilience: Lessons from R-Urban. Build. Res. Inf. 2016, 44, 717–736.

- Remøy, H.; Wandl, A.; Ceric, D.; Van Timmeren, A. Facilitating Circular Economy in Urban Planning. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 1–4.

- Santagata, R.; Zucaro, A.; Viglia, S.; Ripa, M.; Tian, X.; Ulgiati, S. Assessing the sustainability of urban eco-systems through Emergy-based circular economy indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 109, 105859.

- Chen, B.; Sharifi, A.; Schlör, H. Integrated social-ecological-infrastructural management for urban resilience. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106268.

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Barton, D.N. Classifying and valuing ecosystem services for urban planning. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 235–245.

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49.

- Bahers, J.-B.; Athanassiadis, A.; Perrotti, D.; Kampelmann, S. The place of space in urban metabolism research: Towards a spatial turn? A review and future agenda. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 221, 104376.

- Lucertini, G.; Musco, F. Circular Urban Metabolism Framework. One Earth 2020, 2, 138–142.

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pauleit, S.; Naumann, S.; Davis, M.; Artmann, M.; Haase, D.; Knapp, S.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; et al. Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: Perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, art39.

- van den Bosch, M.; Ode Sang, Å. Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health—A systematic review of reviews. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 373–384.

- du Plessis, C. Towards a regenerative paradigm for the built environment. Build. Res. Inf. 2012, 40, 7–22.

- Mazur, Ł. Circular economy in housing architecture: Methods of implementation. ACTA Sci. Pol.-Archit. Bud. 2021, 20, 65–74.

- Mazur, Ł.; Bać, A.; Vaverková, M.D.; Winkler, J.; Nowysz, A.; Koda, E. Evaluation of the Quality of the Housing Environment Using Multi-Criteria Analysis That Includes Energy Efficiency: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 7750.

- Beaugeard, E.; Brischoux, F.; Angelier, F. Green infrastructures and ecological corridors shape avian biodiversity in a small French city. Urban Ecosyst. 2021, 24, 549–560.

- Gill, S.; Handley, J.; Ennos, A.; Pauleit, S. Adapting Cities for Climate Change: The Role of the Green Infrastructure. Built Environ. 2007, 33, 115–133.

- Gu, K.; Fang, Y.; Qian, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wang, A. Spatial planning for urban ventilation corridors by urban climatology. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2020, 6, 1747946.

- Thomson, G.; Newman, P. Green Infrastructure and Biophilic Urbanism as Tools for Integrating Resource Efficient and Ecological Cities. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 75–88.

- Haney, D. Three Acres and a Cow. Small-Scale Agriculture as Solution to Urban Impoverisment in Britian and Germany, 1880–1933. In Food and the City. Histories of Culture and Cultivation; Harvard University Press (Dumbarton Oaks): Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 17–54.

- Howe, J.; Bohn, K.; Viljoen, A. Food in time: The history of english open urban space as a European example. In Continuous Productive Urban Landscapes: Designing Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Cities; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 94–107.

- Katsch, G.; Kosbi, H.; Kroß, E.; Leistner, K.H.; Philipp, R. Geschichte des Kleingartenwesens in Sachsen; Landesverband Sachsen der Kleingärtner e.V: Dresden, Germany, 2007.

- Kononowicz, W.; Gryniewicz-Balińska, K. Historical Allotment Gardens in Wrocław—The Need to Protection. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2016, 21, 43–52.

- Howard, E. To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform; Swan Sonnenschein & Co.: London, UK, 1898.

- Nowysz, A.; Trocka-Leszczyńska, E. Typology of urban agriculture architecture. ACTA Sci. Pol.-Archit. Bud. 2021, 20, 63–71.

- Wang, M.; Yuan, M.; Han, P.; Wang, D. Assessing sustainable urban development based on functional spatial differentiation of urban agriculture in Wuhan, China. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 105999.

- Iles, J. The social role of Community Farms and garden in the city. In CPULs: Continuous Productive Urban Landscapes: Designing Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Cities; Viljoen, A., Howe, J., Bohn, K., Eds.; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 82–88.

- Irvine, S.; Johnson, L.; Peters, K. Community gardens and sustainable land use planning: A case-study of the Alex Wilson community garden. Local Environ. 1999, 4, 33–46.

- Hanna, A.K.; Oh, P. Rethinking Urban Poverty: A Look at Community Gardens. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2000, 20, 207–216.

- Lawson, L. The Planner in the Garden: A Historical View into the Relationship between Planning and Community Gardens. J. Plan. Hist. 2004, 3, 151–176.

- Draper, C.; Freedman, D. Review and Analysis of the Benefits, Purposes, and Motivations Associated with Community Gardening in the United States. J. Community Pract. 2010, 18, 458–492.

- Lawson, L.; Druke, L. From Beets in the Bronx to Chard in Chicago. The Discourse and Practice of Growing Food in American City. In Food and the City. Histories of Culture and Cultivation; Imbert, D., Ed.; Harvard University Press (Dumbarton Oaks): Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 143–162.

- Lawson, L. City Bountiful: A Century of Community Gardening in America; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005.

- Birky, J.; Strom, E. Urban Perennials: How Diversification has Created a Sustainable Community Garden Movement in The United States. Urban Geogr. 2013, 34, 1193–1216.

- Bende, C.; Nagy, G. Effects of community gardens on local society. Belvedere Merid. 2016, 28, 89–105.

- Nordhal, D. Public Produce. The New Urban Agriculture; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Schilling, J. Buffalo as the Nation’s First Living Laboratory for Reclaiming Vacant Properties; The Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Wilkinson, L. Vacant Property: Strategies for Redevelopment in the Contemporary City; Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011.

- Edible School Yard Project. Available online: www.edibleschoolyard.org/network (accessed on 1 January 2018.).

- WORKac. Available online: https://work.ac/featured/ (accessed on 1 January 2018).

- van der Jagt, A.P.N.; Szaraz, L.R.; Delshammar, T.; Cvejić, R.; Santos, A.; Goodness, J.; Buijs, A. Cultivating nature-based solutions: The governance of communal urban gardens in the European Union. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 264–275.

- Calvet-Mir, L.; March, H. Crisis and post-crisis urban gardening initiatives from a Southern European perspective: The case of Barcelona. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2019, 26, 97–112.

- Bell, S.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Keshavarz, N.; Benson, M.; Caputo, S.; Noori, S.; Voigt, A. Urban Allotment Gardens in Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2016.

- Müller, C. Intercultural gardens. Urban places for subsistence production and diversity. Ger. J. Urban Stud. 2007, 46, 58.

- Prinzessinnengärten. Available online: www.prinzessinnengarten.net/about/ (accessed on 1 January 2017).

- Tonkiss, F. Austerity urbanism and the makeshift city. City 2013, 17, 312–324.

- Karge, T. Placemaking and urban gardening: Himmelbeet case study in Berlin. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, 208–222.

- Ulrichs, C.; Mewis, I. Recent Developments in Urban Horticulture—Facts and Fiction. Acta Hortic. 2015, 1099, 925–933.

- Müller, C. Practicing Commons in Community Gardens: Urban Gardening as a Corrective for Homo Economicus. In The Wealth of the Commons a World Beyond Market & State; Bollier, D., Helfrich, S., Eds.; Levellers Press: Amherst, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 219–224.

- Van Dyck, B.; Tornaghi, C.; Halder, S.; von der Haide, E.; Saunders, E. The making of a strategizing platform: From politicizing the food movement in urban contexts to political urban agroecology. In Urban Gardening as Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; p. 19.

- Allmende-Kontor. Available online: www.allmende-kontor.de/index.php/gemeinschaftsgarten.html (accessed on 1 January 2017).

- Škamlová, L.; Wilkaniec, A.; Szczepańska, M.; Bačík, V.; Hencelová, P. The development process and effects from the management of community gardens in two post-socialist cites: Bratislava and Poznań. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 48, 126572.

- Kingsley, J.; Foenander, E.; Bailey, A. “It’s about community”: Exploring social capital in community gardens across Melbourne, Australia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126640.

- Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée. Available online: www.urbantactics.org/about/ (accessed on 1 January 2017).

- Ecobox. Available online: www.ryerson.ca/carrotcity/board_pages/community/ecobox.html (accessed on 1 January 2017).

- Kentish Town City Farm. Available online: www.ktcityfarm.org.uk/about-us/, (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Hackney City Farm. Available online: https://hackneycityfarm.co.uk/ (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Komisar, J.; Nasr, J. Urban design for food systems. Urban Des. Int. 2019, 24, 77–79.

- Miedema, K. Grow small, think big: Designing a local food system for London, Ontario. Urban Des. Int. 2019, 24, 142–155.

- Nowysz, A. Urban vertical farm—Introduction to the subject and discussion of selected examples. ACTA Sci. Pol.-Archit. Bud. 2022, 20, 93–100.

More