The androgen receptor (AR) has a pivotal role in the pathogenesis and progression of PCa. Many therapies targeting AR signaling have been developed over the years. AR signaling inhibitors (ARSIs), including androgen synthesis inhibitors and AR antagonists, have proven to be effective in castration-sensitive PCa (CSPC) and improve survival, but men with castration-resistant PCa (CRPC) continue to have a poor prognosis. Despite a good initial response, drug resistance develops in almost all patients with metastatic CRPC, and ARSIs are no longer effective. Several mechanisms confer resistance to ARSI and include AR mutations but also hyperactivation of other pathways, such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR. This pathway controls key cellular processes, including proliferation and tumor progression, and it is the most frequently deregulated pathway in human cancers.

- prostate cancer

- androgen receptor signaling

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR

- PTEN

1. Introduction

2. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway

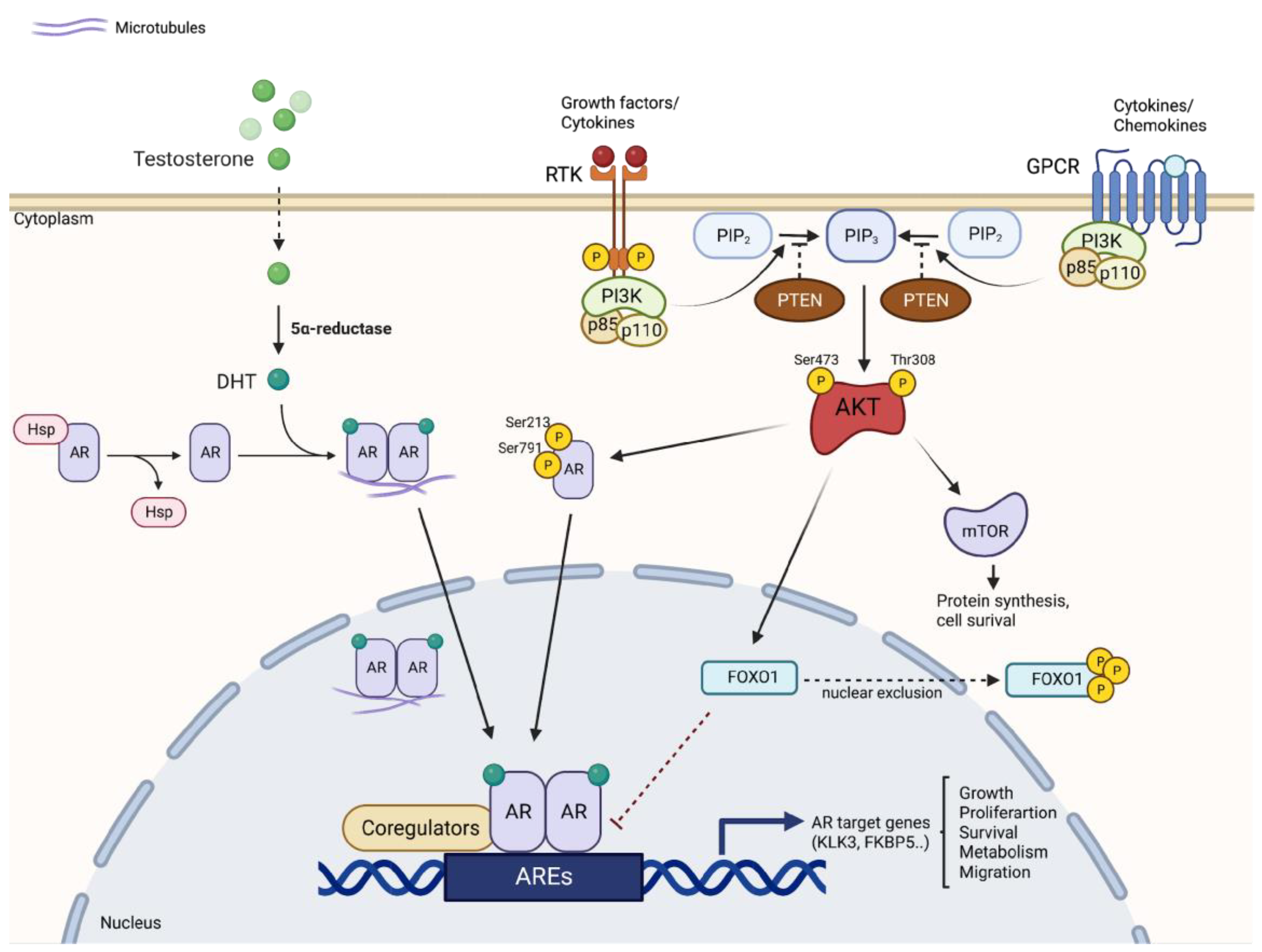

The PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is considered to be a pivotal intracellular signaling pathway and its hyperactivity is correlated with tumor progression in a wide assortment of cancers, counting breast, gastric, ovarian, colorectal, prostate, glioblastoma, and endometrial cancers [24]. PI3K kinase activation constitutes a central mechanism between upstream growth signals and downstream signal transduction mechanisms involved in numerous cellular processes, such as protein synthesis, metabolism, inflammation, cell survival, motility, and tumor progression. PI3K is a large family of lipid enzymes capable of phosphorylating the 3′-OH group of phosphatidylinositol present on the plasma membrane. It was discovered more than 25 years ago and initially associated with the transforming ability of viral oncoproteins. Three classes of PI3Ks (class I, class II, and class III) have been identified in mammals. Kinases belonging to class IA consist of a catalytic subunit and a regulatory subunit. The catalytic subunits p110α, p110β, or p110δ are encoded by the PIK3CA, PIK3CB, and PIK3CD genes, respectively. In contrast, the regulatory subunits consist of p85α (in the isoforms p85α, p55α, p50α), p85β, and p55γ, which are encoded by the PIK3R1, PIK3R2, and PIK3R3 genes. Class IB consists of only one catalytic subunit, P110γ, and two regulatory subunits, p84 and p101 [25]. Class II includes three different monomeric isoforms and remains the most enigmatic of all PI3Ks, although recent studies have provided new clues about its role in signal transduction [26]. Finally, the only member of class III is known as Vps34 (Vacuolar protein signal 34), expressed in all eukaryotic organisms. Vps34 was first discovered in yeast and is implicated in the integration of cellular responses and changes in nutritional status [27]. A variety of signals stimulate PI3K activity, mainly through receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), but also through GPCRs and oncogenes, such as Ras, that directly bind p110. After stimulation, the catalytic subunit of PI3K phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), which acts as a second messenger to recruit a series of proteins containing homology domain with the pleckstrin (PH) of the cell membrane. Uncontrolled signaling of PI3K is very common in cancer, also due to the different roles played by its catalytic subunits p110α and p110β. Mutations in the PI3KA gene encoding p110α have been shown in cancer cells from the colon, lung, prostate, liver, and brain [28]. This gene, in addition to being involved in the processes of cell cycle regulation and growth, acquires a very important role in endothelial cells, promoting angiogenesis and, thus, the formation of a vascular network essential for the delivery of nutrients and oxygen, which can ultimately ensure a pathway of metastasis from the primary lesion. In oncogenesis, the p110α isoform is required for tumors driven by activated receptor tyrosine kinases and oncogenes. The p110β is mainly required for GPCR downstream signaling but it was also found to be essential for the development of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HG-PIN) [29]. In an animal model of Phosphatase and Tensin homolog (PTEN)-deficient PCa, ablation of p110β, but not that of p110α, impeded tumorigenesis, with a concomitant diminution in AKT phosphorylation [30]. Consistently, data from the latest studies suggested that while blockade of p110α had negligible effects in the development of PTEN-null CRPC, genetic or pharmacological disruption of p110β dramatically slowed the initiation and progression of CRPC [29][30][31]. A key molecule in the regulation of PI3K/AKT is PTEN. The function of PTEN as an oncosuppressor is carried out through its phosphatase activity; it dephosphorylates PIP3 to PIP2, negatively regulating the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. This phosphatase can act on both lipids and proteins, and acts by inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis. Mutations to PTEN inhibit its oncosuppressive activity. Two major mutations affect the phosphatase domain: one results in the loss of phosphatase activity on both lipids and proteins while the other impairs phosphatase activity on protein substrates. In addition to regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, PTEN has many other critical roles in tumors, including genomic instability, tumor cell renewal, cell senescence, cell migration, and metastasis. Finally, PTEN plays a significant role in regulating the tumor microenvironment [32]. Mutations in the PTEN gene have been observed in breast, prostate, endometrial, ovarian, colon, melanoma, glioblastoma, and lymphoma cancer [33]. Studies in animal models have also shown that the loss of a single copy of the PTEN gene is sufficient to disrupt cell signaling and initiate uncontrolled cell growth [34]. PI3K activation leads to phosphorylation and then activation of AKT, or protein kinase B (PKB), a serine/threonine kinase of the AGC family of kinases. It exists in three structurally similar isoforms: AKT1, AKT2, and AKT. The three isoforms are composed of characteristic domains. The Pleckstrin Homology (PH) domain has a remarkably conserved tertiary structure, although the amino acid sequence may differ; this domain is responsible for binding to PIP3. The LIN domain, of 39 amino acids is the hinge region connecting the PH domain with the catalytic domain, which is poorly conserved among AKT isoforms (17–46% identical) and has no significant homology with any other human protein. The kinase domain extends from amino acids 148–411 and terminates in a hydrophobic regulatory motif (CTD), ATP-binding portion of the enzyme; the ATP-binding site of 25 residues has 96–100% homology across the three isoforms. The C-terminal hydrophobic domain appears to be conserved in the AGC family of kinases. These hydrophobic residues play a critical role in the complete activation of AKT for substrate phosphorylation. Within it is another key residue for enzyme activation, Ser473. While AKT1 is ubiquitously expressed at high levels, except for the kidney, liver, and spleen, AKT2 expression is high in insulin-sensitive tissues, such as brown fat, skeletal muscle, and liver. AKT3 expression is ubiquitous, although low levels of expression have been found in liver and skeletal muscle. These different isoforms appear to be implicated in specific functions. For example, amplification and overexpression of AKT2 correlate with increased cell motility and invasion, whereas increased AKT3 activity appears to contribute to the aggressiveness of steroid-hormone-insensitive tumors [35]. All three isoforms are activated through phosphorylation: the first occurs on a threonine residue while the second occurs on a serine residue in the hydrophobic motif. Once activated, AKT recognizes and phosphorylates serine or threonine residues of numerous substrates, such as tuberosis sclerosis complex 2 (TSC 2), glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK 3), forkhead box transcription factors (FOXO), p21WAF1/CIP1, p27KIP1, caspase-9, Bcl-2 associated death promoter (BAD), and inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS), which regulate numerous processes that coordinate cell life and death, metabolism, and angiogenesis. Hyperactivation of AKT has been shown in numerous cancers, such as multiple myeloma, lung cancer, glioblastoma, breast cancer, prostate cancer, etc. [36]. The best-studied downstream substrate of AKT is mTOR kinase. AKT can directly phosphorylate and activate mTOR and can cause indirect activation of mTOR by phosphorylating and inactivating tuberous sclerosis 2, also called tuberin (TSC2), which normally inhibits mTOR. The consequence of mTOR activation is increased protein translation [37]. Finally, it has recently been shown that AKT activity can be negatively regulated by the PH domain of leucine repeat sequence-rich phosphatase (PHLPP), which specifically dephosphorylates the hydrophobic motif of AKT (Ser473 in Akt1) [38]. mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) is a serine/threonine kinase that regulates cell growth, proliferation, motility and survival, transcription, and protein synthesis. mTOR plays an important role in regulating the body’s energy balance and weight; it is activated by amino acids, glucose, insulin, and other hormones involved in regulating metabolism. Recent studies have shown that mTOR is not only a substrate of AKT but also a crucial activator of AKT. In fact, mTOR forms a complex (TORC2) with the protein Rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (RICTOR) and then directly phosphorylates the Ser473 of AKT [39]. Activation of TORC2 could then explain the sequestration of newly formed mTOR molecules within cells during long-term rapamycin treatments. In fact, this drug is particularly effective in inducing apoptosis and suppressing the proliferation of AKT-overexpressing cells because, over time, it interferes with the reassembly of the complex by joining it [40].3. Crosstalk between AR and PI3K Signaling

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway has been shown to be deregulated in a wide range of cancers. Genetic alterations have been identified in all components of this signaling pathway. In PCa, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is deregulated in 42% of localized and 100% of advanced disease cases, indicating that alterations in these signals might be an essential prerequisite for the development of CRPC [41]. The existence of negative feedback regulation within AR and PI3K/AKT signaling networks has been demonstrated [42] (Figure 1). Thus, gene mutations and amplifications, and changes in mRNA expression in components of the PI3K pathway, are strictly correlated with the prognosis of PCa patients. For example, reduced expression of PTEN is associated with higher Gleason, biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy, and shorter time to metastatic progression [43]. In addition, high levels of phospho-4EBP1 and eI4E are associated with increased mortality in patients with PCa, indicating that effectors further down the pathway are also predictive of disease progression [44].

Combination Therapy

Because inhibiting either AR or AKT often activates the other, a combination therapy might be advantageous. Over 40 compounds targeting key components in the PI3K-induced signaling pathway have been investigated to date. AZD5363, an inhibitor of all isoforms of Akt, has been reported to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines expressing AR and has antitumor activity in vivo in androgen-sensitive LNCaP xenograft models resistant to castration [54]. However, resistance occurs already after about 30 days of treatment. This is proposed to be since AZD5363 induces an increase in the binding affinity of AR to AREs and an increase in the transcriptional activity of AR and the expression of AR-dependent genes, such as PSA and NKX3.1. These effects were overcome by the combination of AZD5363 and the earlier antiandrogen Bicalutamide, resulting not only in a synergistic inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis in vitro, but also in a prolongation of tumor growth inhibition and PSA stabilization [55]. Moreover, clinical data from the latest ongoing clinical trials support the hypothesis that combinatorial therapies may have a good response in treating advanced PCa. The phase II ProCAID clinical trial suggested that addition of capivasertib (pan-AKT inhibitor) to docetaxel improved OS benefit in mCRPC patients. Median OS was 25.3 months for capivasertib plus docetaxel versus 20.3 months for placebo plus docetaxel (hazard ratio (HR) 0.70, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.47–1.05; nominal p = 0.09) [56]. Another pan-AKT inhibitor, Ipatasertib, has been used in the recent randomized, double-blind, phase III trial combined with abiraterone (IPATential150). This combination led to prolonged radiographic progression-free survival and antitumor activity over a placebo with abiraterone among patients with mCRPC with PTEN loss (median 18.5 vs. 16.5 months, HR = 0.77; p = 0.0335) [57]. The phase I/II study investigating AZD8186, a potent and selective inhibitor of PI3K, supported combination treatment with abiraterone acetate [58]. Moreover, a phase II trial of everolimus (mTOR inhibitor) plus bicalutamide showed encouraging efficacy in men with bicalutamide-naïve CRPC [59]. It must be mentioned, however, that one of the limitations of the use of PI3K/AKT inhibitors is undoubtedly the occurrence of AEs, usually hyperglycemia, rash, and diarrhea. For this reason, numerous studies are focusing on understanding the mechanisms and management of toxicity. In addition, new phase I studies are aimed at optimizing the dosing schedule to improve drug-related toxicity. Noteworthily, most of the clinical trials to date are directed towards patients with advanced or mCRPC, which are very different from the earlier, localized, high-risk disease. Hence, the effects of the combined targeting of AR and PTEN/AKT pathways in the setting of localized prostate cancer need to be investigated.References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33.

- Desai, M.M.; Cacciamani, G.E.; Gill, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Abreu, A.; Gill, I.S. Trends in Incidence of Metastatic Prostate Cancer in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e222246.

- Rebello, R.J.; Oing, C.; Knudsen, K.E.; Loeb, S.; Johnson, D.C.; Reiter, R.E.; Gillessen, S.; Van der Kwast, T.; Bristow, R.G. Prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 7, 9.

- Jemal, A.; Fedewa, S.A.; Ma, J.; Siegel, R.; Lin, C.C.; Brawley, O.W.; Ward, E.M. Prostate Cancer Incidence and PSA Testing Patterns in Relation to USPSTF Screening Recommendations. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2015, 314, 2054–2061.

- Campá, J.; Mar-Barrutia, G.; Extramiana, J.; Arróspide, A.; Mar, J. Advanced prostate cancer survival in Spain according to the Gleason score, age and stage. Actas Urológicas Españolas 2016, 40, 499–506.

- Steele, C.B.; Li, J.; Huang, B.; Weir, H.K. Prostate cancer survival in the United States by race and stage (2001–2009): Findings from the CONCORD-2 study. Cancer 2017, 123, 5160–5177.

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L.; Lin, C.C.; Mariotto, A.B.; Kramer, J.L.; Rowland, J.H.; Stein, K.D.; Alteri, R.; Jemal, A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 271–289.

- Cooperberg, M.R.; Broering, J.M.; Carroll, P.R. Time Trends and Local Variation in Primary Treatment of Localized Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 1117–1123.

- Heidenreich, A.; Bastian, P.J.; Bellmunt, J.; Bolla, M.; Joniau, S.; van der Kwast, T.; Mason, M.; Matveev, V.; Wiegel, T.; Zattoni, F.; et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 467–479.

- Nayak, A.L.; Flaman, A.S.; Mallick, R.; Lavallée, L.T.; Fergusson, D.A.; Cagiannos, I.; Morash, C.; Breau, R.H. Do androgen-directed therapies improve outcomes in prostate cancer patients undergoing radical prostatectomy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2021, 15, 269.

- Crona, D.J.; Whang, Y.E. Androgen Receptor-Dependent and -Independent Mechanisms Involved in Prostate Cancer Therapy Resistance. Cancers 2017, 9, 67.

- Sanda, M.G.; Cadeddu, J.A.; Kirkby, E.; Chen, R.C.; Crispino, T.; Fontanarosa, J.; Freedland, S.; Greene, K.; Klotz, L.H.; Makarov, D.V.; et al. Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline. Part I: Risk Stratification, Shared Decision Making, and Care Options. J. Urol. 2018, 199, 683–690.

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Boorjian, S.A.; Inman, B.; Bagniewski, S.; Bergstralh, E.J.; Blute, M.L. Timing of Androgen Deprivation Therapy and its Impact on Survival After Radical Prostatectomy: A Matched Cohort Study. J. Urol. 2008, 179, 1830–1837.

- Ferraldeschi, R.; Welti, J.; Luo, J.; Attard, G.; de Bono, J.S. Targeting the androgen receptor pathway in castration-resistant prostate cancer: Progresses and prospects. Oncogene 2014, 34, 1745–1757.

- Graham, L.; Schweizer, M.T. Targeting persistent androgen receptor signaling in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Med. Oncol. 2016, 33, 44.

- Polo, S.H.; Muñoz, D.M.; Rodríguez, A.R.; Ruiz, J.S.; Rodríguez, D.R.; Couñago, F. Changing the History of Prostate Cancer with New Targeted Therapies. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 392.

- Attard, G.; Reid, A.H.; A’Hern, R.; Parker, C.; Oommen, N.B.; Folkerd, E.; Messiou, C.; Molife, L.R.; Maier, G.; Thompson, E.; et al. Selective Inhibition of CYP17 With Abiraterone Acetate Is Highly Active in the Treatment of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 3742–3748.

- Crawford, E.D.; Heidenreich, A.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Tombal, B.; Pompeo, A.C.L.; Mendoza-Valdes, A.; Miller, K.; Debruyne, F.M.J.; Klotz, L. Androgen-targeted therapy in men with prostate cancer: Evolving practice and future considerations. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2019, 22, 24–38.

- de Bono, J.S.; Logothetis, C.J.; Molina, A.; Fizazi, K.; North, S.; Chu, L.; Chi, K.N.; Jones, R.J.; Goodman, O.B., Jr.; Saad, F.; et al. Abiraterone and Increased Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1995–2005.

- Beer, T.M.; Armstrong, A.J.; Rathkopf, D.E.; Loriot, Y.; Sternberg, C.N.; Higano, C.S.; Iversen, P.; Bhattacharya, S.; Carles, J.; Chowdhury, S.; et al. Enzalutamide in Metastatic Prostate Cancer before Chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 424–433.

- Sternberg, C.N.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.D.; De Giorgi, U.; Penson, D.F.; Ferreira, U.; Efstathiou, E.; Madziarska, K.; Kolinsky, M.P.; et al. Enzalutamide and Survival in Nonmetastatic, Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2197–2206.

- He, Y.; Xu, W.; Xiao, Y.-T.; Huang, H.; Di Gu, D.; Ren, S. Targeting signaling pathways in prostate cancer: Mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 198.

- Yang, J.; Nie, J.; Ma, X.; Wei, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wei, X. Targeting PI3K in cancer: Mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 26.

- Geering, B.; Cutillas, P.R.; Nock, G.; Gharbi, S.I.; Vanhaesebroeck, B. Class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinases are obligate p85-p110 heterodimers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7809–7814.

- Gewinner, C.; Wang, Z.C.; Richardson, A.; Teruya-Feldstein, J.; Etemadmoghadam, D.; Bowtell, D.; Barretina, J.; Lin, W.M.; Rameh, L.; Salmena, L.; et al. Evidence that Inositol Polyphosphate 4-Phosphatase Type II Is a Tumor Suppressor that Inhibits PI3K Signaling. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 115–125.

- Backer, J.M. The regulation and function of Class III PI3Ks: Novel roles for Vps34. Biochem. J. 2008, 410, 1–17.

- Levine, D.A.; Bogomolniy, F.; Yee, C.J.; Lash, A.; Barakat, R.R.; Borgen, P.I.; Boyd, J. Frequent Mutation of the PIK3CA Gene in Ovarian and Breast Cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 2875–2878.

- Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Ribeiro, C.F.; Manokaran, C.; Chang, H.; Von, T.; Rodrigues, S.; Cizmecioglu, O.; Jia, S.; Korpal, M.; et al. Blocking PI3K p110β Attenuates Development of PTEN-Deficient Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2022, 20, 673–685.

- Jia, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Lee, S.H.; Zhang, J.; Signoretti, S.; Loda, M.; Roberts, T.M.; et al. Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110β in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis. Nature 2008, 454, 776–779.

- Zhao, J.J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Shin, E.; Loda, M.F.; Roberts, T.M. The oncogenic properties of mutant p110α and p110β phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases in human mammary epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18443–18448.

- Conciatori, F.; Bazzichetto, C.; Falcone, I.; Ciuffreda, L.; Ferretti, G.; Vari, S.; Ferraresi, V.; Cognetti, F.; Milella, M. PTEN Function at the Interface between Cancer and Tumor Microenvironment: Implications for Response to Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5337.

- Bunney, T.D.; Katan, M. Phosphoinositide signalling in cancer: Beyond PI3K and PTEN. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 342–352.

- Knowles, M.A.; Platt, F.M.; Ross, R.L.; Hurst, C.D. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway activation in bladder cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009, 28, 305–316.

- Hinz, N.; Jücker, M. Distinct functions of AKT isoforms in breast cancer: A comprehensive review. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019, 17, 1–29.

- Stahl, J.M.; Sharma, A.; Cheung, M.; Zimmerman, M.; Cheng, J.Q.; Bosenberg, M.W.; Kester, M.; Sandirasegarane, L.; Robertson, G.P. Deregulated Akt3 Activity Promotes Development of Malignant Melanoma. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 7002–7010.

- Kim, J.; Guan, K.-L. mTOR as a central hub of nutrient signalling and cell growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 63–71.

- Yan, X.; Li, W.; Yang, L.; Dong, W.; Chen, W.; Mao, Y.; Xu, P.; Li, D.-J.; Yuan, H.; Li, Y.-H. MiR-135a Protects Vascular Endothelial Cells Against Ventilator-Induced Lung Injury by Inhibiting PHLPP2 to Activate PI3K/Akt Pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 48, 1245–1258.

- Sarbassov, D.D.; Ali, S.M.; Kim, D.-H.; Guertin, D.A.; Latek, R.R.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Sabatini, D.M. Rictor, a Novel Binding Partner of mTOR, Defines a Rapamycin-Insensitive and Raptor-Independent Pathway that Regulates the Cytoskeleton. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 1296–1302.

- Yellen, P.; Saqcena, M.; Salloum, D.; Feng, J.; Preda, A.; Xu, L.; Rodrik-Outmezguine, V.; Foster, D.A. High-dose rapamycin induces apoptosis in human cancer cells by dissociating mTOR complex 1 and suppressing phosphorylation of 4E-BP1. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 3948–3956.

- Pungsrinont, T.; Kallenbach, J.; Baniahmad, A. Role of pi3k-akt-mtor pathway as a pro-survival signaling and resistance-mediating mechanism to therapy of prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11088.

- Chandarlapaty, S. Negative Feedback and Adaptive Resistance to the Targeted Therapy of Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 311–319.

- Lotan, T.L.; Carvalho, F.L.; Peskoe, S.B.; Hicks, J.L.; Good, J.; Fedor, H.L.; Humphreys, E.; Han, M.; Platz, E.A.; Squire, J.A.; et al. PTEN loss is associated with upgrading of prostate cancer from biopsy to radical prostatectomy. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28, 128–137.

- Edlind, M.P.; Hsieh, A.C. PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in prostate cancer progression and androgen deprivation therapy resistance. Asian J. Androl. 2014, 16, 378–386.

- Wang, S.; Gao, J.; Lei, Q.-Y.; Rozengurt, N.; Pritchard, C.; Jiao, J.; Thomas, G.V.; Li, G.; Roy-Burman, P.; Nelson, P.S.; et al. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 2003, 4, 209–221.

- Nardella, C.; Carracedo, A.; Alimonti, A.; Hobbs, R.M.; Clohessy, J.G.; Chen, Z.; Egia, A.; Fornari, A.; Fiorentino, M.; Loda, M.; et al. Differential Requirement of mTOR in Postmitotic Tissues and Tumorigenesis. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, ra2.

- Guertin, D.A.; Stevens, D.M.; Saitoh, M.; Kinkel, S.; Crosby, K.; Sheen, J.-H.; Mullholland, D.J.; Magnuson, M.A.; Wu, H.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Complex 2 Is Required for the Development of Prostate Cancer Induced by Pten Loss in Mice. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 148–159.

- El Sheikh, S.S.; Romanska, H.M.; Abel, P.; Domin, J.; Lalani, E.-N. Predictive Value of PTEN and AR Coexpression of Sustained Responsiveness to Hormonal Therapy in Prostate Cancer—A Pilot Study. Neoplasia 2008, 10, 949–953.

- Koryakina, Y.; Ta, H.Q.; Gioeli, D. Androgen receptor phosphorylation: Biological context and functional consequences. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2014, 21, T131–T145.

- Lin, H.-K.; Yeh, S.; Kang, H.-Y.; Chang, C. Akt suppresses androgen-induced apoptosis by phosphorylating and inhibiting androgen receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 7200–7205.

- Carver, B.S.; Chapinski, C.; Wongvipat, J.; Hieronymus, H.; Chen, Y.; Chandarlapaty, S.; Arora, V.K.; Le, C.; Koutcher, J.; Scher, H.; et al. Reciprocal Feedback Regulation of PI3K and Androgen Receptor Signaling in PTEN-Deficient Prostate Cancer. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 575–586.

- Newton, A.C.; Trotman, L.C. Turning off AKT: PHLPP as a drug target. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 54, 537–558.

- Serra, V.; Scaltriti, M.; Prudkin, L.; Eichhorn, P.; Ibrahim, Y.H.; Chandarlapaty, S.; Markman, B.; Rodriguez, O.; Guzman, M.; Gili, M.; et al. PI3K inhibition results in enhanced HER signaling and acquired ERK dependency in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Oncogene 2011, 30, 2547–2557.

- Toren, P.; Kim, S.; Cordonnier, T.; Crafter, C.; Davies, B.R.; Fazli, L.; Gleave, M.E.; Zoubeidi, A. Combination AZD5363 with Enzalutamide Significantly Delays Enzalutamide-resistant Prostate Cancer in Preclinical Models. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 986–990.

- Thomas, C.; Lamoureux, F.; Crafter, C.; Davies, B.R.; Beraldi, E.; Fazli, L.; Kim, S.; Thaper, D.; Gleave, M.E.; Zoubeidi, A. Synergistic Targeting of PI3K/AKT Pathway and Androgen Receptor Axis Significantly Delays Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Progression In Vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 2342–2355.

- Crabb, S.J.; Griffiths, G.; Dunkley, D.; Downs, N.; Ellis, M.; Radford, M.; Light, M.; Northey, J.; Whitehead, A.; Wilding, S.; et al. Overall Survival Update for Patients with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Treated with Capivasertib and Docetaxel in the Phase 2 ProCAID Clinical Trial. Eur. Urol. 2022, 82, 512–515.

- Sweeney, C.; Bracarda, S.; Sternberg, C.N.; Chi, K.N.; Olmos, D.; Sandhu, S.; Massard, C.; Matsubara, N.; Alekseev, B.; Parnis, F.; et al. Ipatasertib plus abiraterone and prednisolone in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (IPATential150): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 131–142.

- De Bono, J.; Hansen, A.; Choudhury, A.; Cook, N.; Heath, E.; Higano, C.; Linch, M.; Martin-Liberal, J.; Rathkopf, D.; Wisinski, K.; et al. AZD8186, a potent and selective inhibitor of PI3Kβ/δ, as monotherapy and in combination with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone (AAP), in patients (pts) with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, viii291–viii292.

- Chow, H.; Ghosh, P.M.; deVere White, R.; Evans, C.P.; Dall’Era, M.A.; Yap, S.A.; Li, Y.; Beckett, L.A.; Lara, P.N., Jr.; Pan, C.X. A Phase II clinical trial of everolimus plus bicalutamide for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer 2016, 122, 1897–1904.