Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Sirius Huang and Version 2 by Zhihua Zheng.

Drug-related problems (DRPs) are common among surgical patients, especially older patients with polypharmacy and underlying diseases. DRPs can potentially lead to morbidity, mortality, and increased treatment costs. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) system has shown great advantages in managing surgical patients. Medication therapy management for surgical patients is an important part of the ERAS system. Improper medication therapy management can lead to serious consequences and even death.

- surgical pharmacy

- ERAS

- pharmacist

- perioperative medication therapy

1. Introduction

Despite continuous advances in surgery, anesthesia, and perioperative care, undesirable complications during and after major surgery, such as pain, thrombogenesis, nausea, and gastrointestinal paralysis, continue to present major challenges. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) system has shown great advantages in managing surgical patients. This system refers to a series of optimized clinical pathways with evidence-based medicine (EBM) adopted in perioperative care to overcome the deleterious effect of perioperative stress, accelerate postoperative rehabilitation, reduce postoperative complications, shorten hospital stays, and reduce medical costs [1,2][1][2]. The concept of ERAS has spread to different surgical specialties and is widely used in patients receiving surgical operations. A multidisciplinary team (MDT), including surgery, anesthesia, pharmacy, nursing, rehabilitation, nutrition, and psychology, with team members made up of doctors, pharmacists, nurses, rehabilitation therapists, and dietitians, is required in the ERAS program, especially in cases of major surgery [2,3,4,5][2][3][4][5].

Medication therapy management is essential for surgery. Perioperative pain, nausea and vomiting, anticoagulation, anti-infection, blood pressure management, blood glucose management, nutrition management, fluid management and other aspects are all considered in medication therapy, as well as problems related to medication therapy. However, drug-related problems (DRPs) are common among hospitalized patients, potentially leading to morbidity, mortality, and increased treatment costs [6,7,8,9,10][6][7][8][9][10]. Patients attending surgical wards are especially at risk due to the need for pain medication, antibiotics, and frequent adjustments of antithrombotic regimens [8]. Mohammed et al., reported that up to 69.5% of patients had at least one DRP during their hospital stay among elective surgical patients [8]. In addition, polypharmacy is increasingly prevalent in older patients [11,12][11][12]. It was reported that polypharmacy occurred in 54.8% of older patients (≥65 years old) with elective noncardiac surgery [12]. Pharmaceutical interventions can significantly decrease DRPs and have an average cost savings of USD 1511 per case by identifying and resolving DRPs [13,14][13][14]. Therefore, in order to reduce DRPs, morbidity, and patient costs and promote the rapid recovery of surgical patients, there is a great need for the medication therapy management services of surgical pharmacy in the ERAS programs. Surgical pharmacy is a discipline established by the Guangdong Province Pharmaceutical Association in 2021 [19][15].

2. Perioperative Medication Therapy

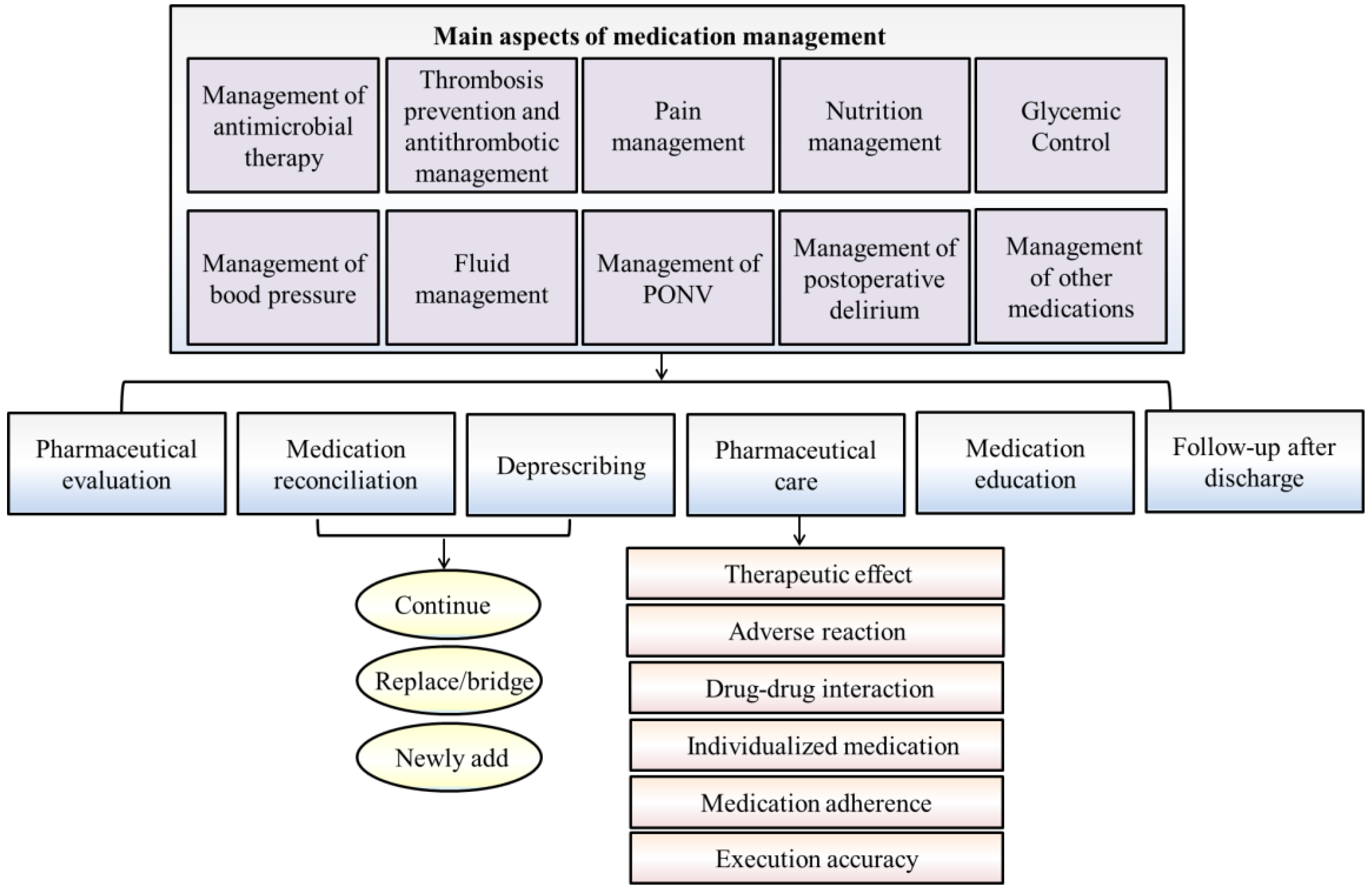

Perioperative medication therapy mainly includes antimicrobial agents, antithrombotic agents, pain medication, nutritional therapy, blood glucose monitoring, blood pressure treatment, fluid management, treatment of nausea and vomiting, and management of postoperative delirium. The aspects of surgical pharmacists’ involvement are summarized as follows (Figure 1).

2.1. Management of Antimicrobial Therapy

Surgical site infection (SSI) is a common postoperative complication and is the third most common nosocomial infection [75][17]. It was reported that SSI accounts for approximately 15–25% of all nosocomial infections and approximately 37% of the infections that occur in surgical patients [20,21,22][18][19][20]. The use of perioperative antibiotics is thought to be an important means to decrease wound infection. However, the irrational use of antibiotics can not only prolong the recovery time but also lead to the serious effects of antibiotic resistance [23][21].

According to the guiding principles for the clinical use of antibiotics (version 2015) [76][22], the use of prophylactic antibiotics should follow the principles of preventive medication and should be based on the type of surgical incision, the degree of surgical trauma, the type of possible contaminating bacteria, the duration of the operation, the chance of infection, the severity of the consequences, the levels of evidence for antimicrobial prophylaxis, the influence of drug resistance, economic evaluation and other factors. The need for the prophylactic medication of antibacterial drugs, appropriate antibacterial drugs and appropriate dosing regimens should be considered comprehensively.

2.2. Thrombosis Prophylaxis and Antithrombotic Management

Surgery is a well-recognized risk factor for thromboembolic disease. Since surgical patients are significantly more likely to develop venous thromboembolism (VTE) than ambulatory patients and experience higher rates of VTE recurrence and bleeding complications during VTE treatment, a trade-off must be considered in perioperative anticoagulant management. Existing evidence suggests that a targeted prophylaxis/treatment strategy based on patient-level variations would optimize the patient’s risk/benefit relationship and improve perioperative patient management [24][23]. However, the perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy, including anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents, often presents a dilemma for clinical practice. Although there is a relative paucity of well-designed clinical trials to inform the best perioperative practices in this area, most patients undergoing surgery are likely to benefit from pharmacologic prophylaxis [25][24]. The ninth edition of the ACCP guidelines on VTE risk assessment and prevention specifically recommends the Caprini score to quantify VTE risk and make prophylaxis recommendations for perioperative patients.

2.3. Pain Management

Postoperative pain is acute pain that occurs immediately after surgery. Both undertreatment and overtreatment of acute postoperative pain can lead to severe consequences. Good pain management can reduce postoperative stress, accelerate the recovery of intestinal function, promote early recovery of patients, and improve the quality of life of patients after surgery [77][25]. Medication is essential in the treatment of pain. Postoperative analgesia needs to consider the following factors comprehensively: age, anxiety level, surgical method and process, individual body condition, and response to drugs or treatment [31,32,33,34,35][26][27][28][29][30]. During the perioperative period, the pain severity of patients and the efficacy of analgesic drugs should be dynamically assessed, and adverse reactions should be monitored. Analgesic drugs should be evaluated for adequacy and excess, and the medication regimen should be modified in time.

2.4. Nutrition Management

In surgical patients, especially in elderly individuals, malignant tumors, gastrointestinal diseases, and nervous system diseases are all commonly associated with a high malnutrition risk [36,78][31][32]. Nutritional status is an independent and effective indicator for predicting the incidence and mortality of perioperative complications [79,80,81][33][34][35]. In addition, the malnutrition risk in hospitalized patients was > 40% and higher after discharge [82][36]. Therefore, during the perioperative period, nutritional risk screening and assessment should be performed, and patients with nutritional risk should be given timely consideration and intervention.

2.5. Glycemic Control

Surgical patients frequently experience hyperglycemia, and undiagnosed insulin resistance is identified on the day of surgery (DOS) [83,84][37][38]. Surgical patients with diabetes are increasingly common and are more likely to present with glycemic control challenges [85][39]. Studies have shown that perioperative dysglycemia is associated with adverse postoperative clinical outcomes, including an increased incidence of postoperative infection, delayed wound healing, poor postoperative recovery and prolonged hospital stay, as well as an increased risk of surgery and perioperative mortality [84,86,87,88][38][40][41][42]. There is a 30% increased risk of adverse events for each 20-mg/dL increase in the mean glucose level [89,90][43][44]. Good glycemic control in the perioperative period is of great significance in improving the prognosis of patients.

2.6. Management of Blood Pressure

Perioperative blood pressure fluctuations directly affect the prognosis of patients. Good blood pressure control is of great significance for preventing intraoperative complications and improving the prognosis of patients. Abnormal fluctuations in perioperative blood pressure include hypertension and hypotension. Perioperative hypertension is usually caused by increased activity or insufficient inhibition of the autonomic nervous system and is related to patients’ emotions, such as tension and anxiety, primary hypertension, secondary hypertension, volume overload, anesthesia and other influencing factors [51][45]. Perioperative hypotension is relative to the patient’s basic blood pressure. It is related to the patient’s underlying diseases, the use of anesthesia or anesthetic drugs, neuroreflex hypotension, postural hypotension, supine hypotension syndrome, surgery and other factors, which can cause hypoperfusion of tissues and organs, and increase the risk of postoperative delirium, stroke, myocardial ischemia, myocardial infarction, acute kidney injury and postoperative mortality [52][46].

2.7. Fluid Management

The normal metabolism of water, electrolytes and acid-base balance in the human body are important factors in maintaining the stability of the body’s internal environment, which is an indispensable condition for the normal life activities of the body. Insufficient infusion can cause hypoperfusion, microcirculation disorders, and organ insufficiency in patients with heart, kidney, brain and other vital organs. Excessive infusion can cause postoperative intra-abdominal hypertension and interstitial edema, affect the healing of anastomosis and the recovery of gastrointestinal function, and increase the probability of systemic infection, both of which can lead to increased postoperative morbidity and mortality [55,56][47][48].

The goal of perioperative fluid therapy in the ERAS protocol is to maintain the homeostasis of body fluids and avoid postoperative complications and gastrointestinal dysfunction due to fluid overload or organ insufficiency. In the perioperative period, a goal-directed circulatory management strategy is advocated, especially for complex surgery and critically ill patients [57][49].

2.8. Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) were found in approximately 30% of general surgical patients and as high as 80% of high-risk patients, which can lead to electrolyte disorders, wound dehiscence, esophageal rupture and delayed discharge time [91][50]. It was reported that risk factors for PONV included age (<50 years old), female sex, nonsmoker, history of motion sickness or PONV, opioid analgesia and surgery type [59][51]. For the selection and use of PONV drugs, the risk of PONV should first be assessed in patients. It was recommended that multimodal prophylaxis be used in patients with one or more risk factors [60][52]. In ERAS pathways, multimodal prophylactic antiemetics are recommended [60][52].

2.9. Management of Postoperative Delirium

Delirium is a common and harrowing complication during the postoperative period, especially in older patients. Postoperative delirium occurs in 17–61% of major surgeries, which may cause cognitive decline, prolonged length of stay (LOS), decreased functional independence, increased risk of dementia, caregiver burden, health care costs, morbidity and mortality [92,93][53][54]. Older age, dementia (often not recognized clinically), frailty, functional disabilities, the severity of concurrent illness, type of operation, ICU admission after surgery, a high burden of coexisting conditions and postoperative pain are common predisposing factors [64,65][55][56]. Male sex, poor vision and hearing, depressive symptoms, mild cognitive impairment, laboratory abnormalities, and alcohol abuse have also been associated with increased risk [66][57]. Delirium can be prevented, and 30–40% of cases are assumed to be preventable before its onset [94][58]. Pharmacological prevention and treatment are important aspects.

References

- Klek, S.; Salowka, J.; Choruz, R.; Cegielny, T.; Welanyk, J.; Wilczek, M.; Szczepanek, K.; Pisarska-Adamczyk, M.; Pedziwiatr, M. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) Protocol Is a Safe and Effective Approach in Patients with Gastrointestinal Fistulas Undergoing Reconstruction: Results from a Prospective Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1953.

- Ljungqvist, O.; Scott, M.; Fearon, K.C. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2017, 152, 292–298.

- Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Chang, C.; Liu, C.; Li, K.; Hu, J. Barriers to implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) by a multidisciplinary team in China: A multicentre qualitative study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053687.

- Francis, N.K.; Walker, T.; Carter, F.; Hubner, M.; Balfour, A.; Jakobsen, D.H.; Burch, J.; Wasylak, T.; Demartines, N.; Lobo, D.N.; et al. Consensus on Training and Implementation of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery: A Delphi Study. World J. Surg. 2018, 42, 1919–1928.

- Roulin, D.; Najjar, P.; Demartines, N. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Implementation: From Planning to Success. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2017, 27, 876–879.

- Hoonhout, L.H.; de Bruijne, M.C.; Wagner, C.; Asscheman, H.; van der Wal, G.; van Tulder, M.W. Nature, occurrence and consequences of medication-related adverse events during hospitalization: A retrospective chart review in the Netherlands. Drug Saf. 2010, 33, 853–864.

- Krahenbuhl-Melcher, A.; Schlienger, R.; Lampert, M.; Haschke, M.; Drewe, J.; Krahenbuhl, S. Drug-related problems in hospitals: A review of the recent literature. Drug Saf. 2007, 30, 379–407.

- Mohammed, M.; Bayissa, B.; Getachew, M.; Adem, F. Drug-related problems and determinants among elective surgical patients: A prospective observational study. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10, 20503121221122438.

- Davies, E.C.; Green, C.F.; Taylor, S.; Williamson, P.R.; Mottram, D.R.; Pirmohamed, M. Adverse drug reactions in hospital in-patients: A prospective analysis of 3695 patient-episodes. PloS ONE 2009, 4, e4439.

- Miguel, A.; Azevedo, L.F.; Araujo, M.; Pereira, A.C. Frequency of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2012, 21, 1139–1154.

- Barlow, A.; Prusak, E.S.; Barlow, B.; Nightingale, G. Interventions to reduce polypharmacy and optimize medication use in older adults with cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 863–871.

- McIsaac, D.I.; Wong, C.A.; Bryson, G.L.; van Walraven, C. Association of Polypharmacy with Survival, Complications, and Healthcare Resource Use after Elective Noncardiac Surgery: A Population-based Cohort Study. Anesthesiology 2018, 128, 1140–1150.

- Bos, J.M.; van den Bemt, P.M.; Kievit, W.; Pot, J.L.; Nagtegaal, J.E.; Wieringa, A.; van der Westerlaken, M.M.; van der Wilt, G.J.; de Smet, P.A.; Kramers, C. A multifaceted intervention to reduce drug-related complications in surgical patients. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 664–677.

- Dagnew, S.B.; Binega Mekonnen, G.; Gebeye Zeleke, E.; Agegnew Wondm, S.; Yimer Tadesse, T. Clinical Pharmacist Intervention on Drug-Related Problems among Elderly Patients Admitted to Medical Wards of Northwest Ethiopia Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals: A Multicenter Prospective, Observational Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 8742998.

- Zheng, Z.; Wu, J.; Wei, L.; Li, X.; Ji, B.; Wu, H. Surgical pharmacy: The knowledge system of surgical pharmacists. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2023, 30, e2.

- Guangdong Province Pharmaceutical Association. Consensus of medical experts on the management of perioperative medication therapy in ERAS. Pharm. Today 2020, 30, 361–371. (In Chinese)

- Mangram, A.J.; Horan, T.C.; Pearson, M.L.; Silver, L.C.; Jarvis, W.R. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 1999, 20, 250–278.

- Bratzler, D.W.; Houck, P.M.; Surgical Infection Prevention Guideline Writers, W. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: An advisory statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Am. J. Surg. 2005, 189, 395–404.

- Kaiser, A.B. Surgical-wound infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 123–124.

- Young, P.Y.; Khadaroo, R.G. Surgical site infections. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 94, 1245–1264.

- Allen, M.S. Perioperative antibiotics: When, why? Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2005, 15, 229–235, vi.

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China; State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of the People’s Republic of China; Medical Department of the People’s Liberation Army General Logistics Department. Guiding Principles for Clinical Use of Antibiotic (Version 2015) (In Chinese). 2015. Available online: https://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s3593/201508/c18e1014de6c45ed9f6f9d592b43db42.shtml (accessed on 27 August 2015).

- Farge, D.; Frere, C.; Connors, J.M.; Khorana, A.A.; Kakkar, A.; Ay, C.; Munoz, A.; Brenner, B.; Prata, P.H.; Brilhante, D.; et al. 2022 international clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer, including patients with COVID-19. Lancet. Oncol. 2022, 23, e334–e347.

- Liu, M.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Guo, N.; Han, C.; Peng, Y.; Yang, M.; Liu, Y.; et al. Efficacy and safety of thromboprophylaxis in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835920907540.

- Beloeil, H.; Sulpice, L. Peri-operative pain and its consequences. J. Visc. Surg. 2016, 153, S15–S18.

- Mitra, S.; Carlyle, D.; Kodumudi, G.; Kodumudi, V.; Vadivelu, N. New Advances in Acute Postoperative Pain Management. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2018, 22, 35.

- Joshi, G.P.; Kehlet, H. Postoperative pain management in the era of ERAS: An overview. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 33, 259–267.

- Tan, M.; Law, L.S.; Gan, T.J. Optimizing pain management to facilitate Enhanced Recovery after Surgery pathways. Can. J. Anaesth. 2015, 62, 203–218.

- Amaechi, O.; Huffman, M.M.; Featherstone, K. Pharmacologic Therapy for Acute Pain. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 104, 63–72.

- Blondell, R.D.; Azadfard, M.; Wisniewski, A.M. Pharmacologic therapy for acute pain. Am. Fam. Physician 2013, 87, 766–772.

- Weimann, A.; Braga, M.; Carli, F.; Higashiguchi, T.; Hubner, M.; Klek, S.; Laviano, A.; Ljungqvist, O.; Lobo, D.N.; Martindale, R.G.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4745–4761.

- Benoist, S.; Brouquet, A. Nutritional assessment and screening for malnutrition. J. Visc. Surg. 2015, 152 (Suppl. S1), S3–S7.

- Lew, C.C.H.; Yandell, R.; Fraser, R.J.L.; Chua, A.P.; Chong, M.F.F.; Miller, M. Association between Malnutrition and Clinical Outcomes in the Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review . JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2017, 41, 744–758.

- Skeie, E.; Tangvik, R.J.; Nymo, L.S.; Harthug, S.; Lassen, K.; Viste, A. Weight loss and BMI criteria in GLIM’s definition of malnutrition is associated with postoperative complications following abdominal resections—Results from a National Quality Registry. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 1593–1599.

- Kakavas, S.; Karayiannis, D.; Bouloubasi, Z.; Poulia, K.A.; Kompogiorgas, S.; Konstantinou, D.; Vougas, V. Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition Criteria Predict Pulmonary Complications and 90-Day Mortality after Major Abdominal Surgery in Cancer Patients. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3726.

- Beser, O.F.; Cokugras, F.C.; Erkan, T.; Kutlu, T.; Yagci, R.V. Evaluation of malnutrition development risk in hospitalized children. Nutrition 2018, 48, 40–47.

- Levetan, C.S.; Passaro, M.; Jablonski, K.; Kass, M.; Ratner, R.E. Unrecognized diabetes among hospitalized patients. Diabetes Care 1998, 21, 246–249.

- Frisch, A.; Chandra, P.; Smiley, D.; Peng, L.; Rizzo, M.; Gatcliffe, C.; Hudson, M.; Mendoza, J.; Johnson, R.; Lin, E.; et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of hyperglycemia in the perioperative period in noncardiac surgery. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1783–1788.

- Smiley, D.D.; Umpierrez, G.E. Perioperative glucose control in the diabetic or nondiabetic patient. South. Med. J. 2006, 99, 580–589, quiz 590–581.

- Noordzij, P.G.; Boersma, E.; Schreiner, F.; Kertai, M.D.; Feringa, H.H.; Dunkelgrun, M.; Bax, J.J.; Klein, J.; Poldermans, D. Increased preoperative glucose levels are associated with perioperative mortality in patients undergoing noncardiac, nonvascular surgery. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2007, 156, 137–142.

- Kwon, S.; Thompson, R.; Dellinger, P.; Yanez, D.; Farrohki, E.; Flum, D. Importance of perioperative glycemic control in general surgery: A report from the Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 8–14.

- Raju, T.A.; Torjman, M.C.; Goldberg, M.E. Perioperative blood glucose monitoring in the general surgical population. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2009, 3, 1282–1287.

- Gandhi, G.Y.; Nuttall, G.A.; Abel, M.D.; Mullany, C.J.; Schaff, H.V.; Williams, B.A.; Schrader, L.M.; Rizza, R.A.; McMahon, M.M. Intraoperative hyperglycemia and perioperative outcomes in cardiac surgery patients. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2005, 80, 862–866.

- Himes, C.P.; Ganesh, R.; Wight, E.C.; Simha, V.; Liebow, M. Perioperative Evaluation and Management of Endocrine Disorders. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 2760–2774.

- Saugel, B.; Sessler, D.I. Perioperative Blood Pressure Management. Anesthesiology 2021, 134, 250–261.

- Saugel, B.; Kouz, K.; Hoppe, P.; Maheshwari, K.; Scheeren, T.W.L. Predicting hypotension in perioperative and intensive care medicine. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 33, 189–197.

- Brandstrup, B.; Tønnesen, H.; Beier-Holgersen, R.; Hjortsø, E.; Ørding, H.; Lindorff-Larsen, K.; Rasmussen, M.S.; Lanng, C.; Wallin, L.; Iversen, L.H.; et al. Effects of intravenous fluid restriction on postoperative complications: Comparison of two perioperative fluid regimens: A randomized assessor-blinded multicenter trial. Ann. Surg. 2003, 238, 641–648.

- Asklid, D.; Segelman, J.; Gedda, C.; Hjern, F.; Pekkari, K.; Gustafsson, U.O. The impact of perioperative fluid therapy on short-term outcomes and 5-year survival among patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery—A prospective cohort study within an ERAS protocol. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Assoc. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 43, 1433–1439.

- Scheib, S.A.; Thomassee, M.; Kenner, J.L. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery in Gynecology: A Review of the Literature. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 327–343.

- Sizemore, D.C.; Singh, A.; Dua, A.; Singh, K.; Grose, B.W. Postoperative Nausea. In StatPearls, © 2023; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022.

- Apfel, C.C.; Heidrich, F.M.; Jukar-Rao, S.; Jalota, L.; Hornuss, C.; Whelan, R.P.; Zhang, K.; Cakmakkaya, O.S. Evidence-based analysis of risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br. J. Anaesth. 2012, 109, 742–753.

- Gan, T.J.; Belani, K.G.; Bergese, S.; Chung, F.; Diemunsch, P.; Habib, A.S.; Jin, Z.; Kovac, A.L.; Meyer, T.A.; Urman, R.D.; et al. Fourth Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, 411–448.

- De Lange, E.; Verhaak, P.F.; van der Meer, K. Prevalence, presentation and prognosis of delirium in older people in the population, at home and in long term care: A review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 127–134.

- Siddiqi, N.; House, A.O.; Holmes, J.D. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: A systematic literature review. Age Ageing 2006, 35, 350–364.

- Janssen, T.L.; Alberts, A.R.; Hooft, L.; Mattace-Raso, F.; Mosk, C.A.; van der Laan, L. Prevention of postoperative delirium in elderly patients planned for elective surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 1095–1117.

- Johnson, J.R. Delirium in Hospitalized Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 96.

- Allen, S.R.; Frankel, H.L. Postoperative complications: Delirium. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 92, 409–431.

- Inouye, S.K.; Westendorp, R.G.; Saczynski, J.S. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014, 383, 911–922.

More