Aligned to their traditional uses as antiparasitic agents, halophytes have proven by in vitro and in vivo research approaches their potential as sources of molecules with activity towards different protozoa species. Most antiprotozoal studies on natural products focus particularly on neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), a group of twenty infectious illnesses that include, for example, leishmaniasis, human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), Chagas disease, and schistosomiasis. NTDs affect more than 1 billion people worldwide, particularly very poor populations in tropical and subtropical areas in 149 countries). Leishmaniasis is caused by more than 20 Leishmania species, while trypanosomiasis is ascribed to Trypanosoma, either the Trypanosoma brucei complex (sleeping sickness, human African trypanosomiasis) or T. cruzi (Chagas disease, American trypanosomiasis). Malaria, referred to as a “disease of poverty”, is no longer recognized as an NTD and is caused by protozoa of the genus Plasmodium, namely P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. ovale, which are specific for humans.

- halophyte plants

- diseases

- halophyte species

- antiparasitic

- salt tolerant plants

1. In Vitro Activities and Bioactive Constituents

| Family/Species | Plant Organ | Extract/Fraction/Compound | Chemical Components | Protozoal Species | Results * | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | ||||||

| Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants (syn. Chenopodium ambrosioides L.) | Aerial organs | Essential oil | Terpinolene | L. amazonensis, L. donovani | Epimastigotes (IC50 = 21.3 µg/mL), and trypomastigotes (IC50 = 28.1 µg/mL) | [7][49] |

| T. cruzi | Epimastigotes (IC50 = 21.3 µg/mL), trypomastigotes (IC50 = 28.1 µg/mL), and amastigotes (IC50 = 50.2 µg/mL) | [7][49] | ||||

| Aerial parts containing immature seeds | Ethanol ethylacetate extract | Ascaridole [8][1]; (−)-(2S,4S)-p-mentha-1(7),8-dien-2-hydroperoxide [9][2]; (−)-(2R,4S)-p-mentha-1(7),8-dien-2-hydroperoxide [10][3] (−)-(1R,4S)-p-mentha-2,8-dien-1-hydroperoxide [11][4] (−)-(1S,4S)-p-mentha-2,8-dien-1-hydroperoxide [12][5]. |

T. cruzi (epimastigotes) | MLC [8][1] = 23 μM; MLC [9][2] = 1.2 μM; MLC [10][3] = 1.6 μM; MLC [11][4]= 3.1 μM; and MLC [12][5]= 0.8 μM |

[13][50] | |

| Leaves | Hydroalchoholic extract | ND | Giardia lamblia (trophozoites) | IC50 = 198 µg/mL | [14][33] | |

| Leaves | 70 % Ethanol extract | ND | Plasmodium falciparum | IC50 = 25.4 μg/mL | [15][51] | |

| Leaves | Essential oil | Ascaridole | Entamoeba histolytica (trophozoites) | IC50 = 700 µg/mL | [16][52] | |

| Anacardiaceae | ||||||

| Pistacia lentiscus L. | Leaves and fruits | Essential oil | Leaves: Myrcene and α-pinene; Fruits: α-pinene and limonene | Leishmania major, L. tropica, L. infantum (clinical isolates) | IC50 = 8–26.2 µg/mL | [3][45] |

| Leaves | Essential oil | α-pinene, β-myrcene, D-limonene, o-cymene, terpinen-4- ol, β-pinene, α-phellandrene | Leishmania major | Intramacrophage amastigote: IC50 = 12.5–35.6 µg/mL; Axenic amastigote: IC50 = 0.5–56.1 µg/mL | [6][48] | |

| Apiaceae | ||||||

| Crithmum maritimum L. | Aerial organs | Essential oil | Limonene, γ-terpinene and sabinene | Trypanossoma brucei | IC50 = 5.0 µg/mL | [1][43] |

| Limonene, sabinene | Limonene: EC50 = 5.6 µM Sabinene: EC50 = 6.0 µM |

|||||

| Aerial organs | Essential oil | α-pinene, p-cymene β-phellandrene, Z-β -ocimene, γ-terpinene, thymyl-methyl oxide, dillapiole | L. infantum (promastigotes) | IC50 = 122 µg/mL | [2][44] | |

| Flowers | Decoction | Falcarindiol | Trypanosoma cruzi | Extract: EC50 = 17.7 µg/mL, SI > 5.65 Fraction: EC50 = 0.47 µg/mL, SI = 59.6 |

[17][53] | |

| Eryngium maritimum L. | Aerial organs | Essential oil | α-pinene, germacrene D, bicyclogermacrene, germacrene, δ-cadinene | L. infantum (promastigotes) | IC50 = 205 µg/mL | [2][44] |

| Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Seeds | Essential oil, n-hexane, methanol, and water extracts | E-anethole | Trichomonas vaginalis | Methanol and hexane extracts: MLC = 360 µg/mL Essential oil and anethole: MLC = 1600 µg/ml |

[18][54] |

| Seeds | Water extract | Hesperidin, ferulic acid, chlorogenic acid | Blastocystis spp. | 48h: IC50 = 224 µg/mL; 72h: IC50 = 175 µg/mL | [19][55] | |

| Asteraceae | ||||||

| Inula crithmoides L. | Aerial organs | Dichloromethane extract | Gallic, syringic, salicylic caffeic, coumaric, and rosmarinic acids; epicatechin, epigalocatechin gallate, catechin hydrate, quercetin, and apigenin | Leishmania infantum | Intracellular amastigotes: 70% at 125 µg/mL; Promastigotes: 26.5% at 125 µg/mL | [20][56] |

| Caryophyllaceae | ||||||

| Spergularia rubra (L.) J.Presl & C.Presl and | Aerial organs | Dichloromethane extract | Catechin hydrate | Leishmania infantum | Intracellular amastigotes: 25% at 125 µg/mL; promastigotes: 16.7% at 125 µg/mL | [20][56] |

| Cyperaceae | ||||||

| Cyperus rotundus L. | Tuber of root | Ethyl acetate extract | ND | Plasmodium falciparum | Sensitive strain 3D7: IC50 = 5.1 µg/mL; resistant strain INDO: IC50 = 4 µg/mL | [21][57] |

| Combretaceae | ||||||

| Laguncularia racemosa (L.) C.F. Gaertn. | Leaves | Chloroform:methanol (1:1) extract | Triterpenoids, phenols | P. falciparum | 60.1 % at 6.25 μg/mL | [22][58] |

| Fabaceae | ||||||

| Glycyrrhiza glabra L. | Roots | Water extract | Licochalcone A | Leishmania major (promastigotes) | Extract: > 90% death at 1:100 and 1:200 dilutions | [23][59] |

| L. donovani (promastigotes) | > 90% death at 1:100 dilution | [23][59] | ||||

| Licochalcone A | L. major | Amastigotes: 0 % infection at 5 and 10 μg/mL Promastigotes: 0.4 % at 1:100 |

[23][59] | |||

| Juncaceae | ||||||

| Juncus acutus L. | Roots | Dichloromethane extract and Fraction 8 | Phenanthrenes, dihydrophenanthrenes, and benzocoumarins | Trypanosoma cruzi (trypomastigotes) | Extract: IC50 < 20 µg/mL; Fraction 8: IC50 = 4.1 µg/mL, SI: 1.5 | [24][60] |

| Nitrariaceae | ||||||

| Peganum harmala L. | Seeds | Water extract | ND | L. major (Promastigotes, amastigotes) |

Promastigotes: IC50 = 40 µg/mL; Amastigotes: 50% reduction of infection at 10 and 40 µg/mL at 48h | [25][61] |

| Seeds | Hydroalchoholic extract | Harmaline, harmine, and beta-carboline | L. major (promastigotes) |

IC50 = 59.4 µg/mL | [26][62] | |

| Seeds | Water extract | ND | L. donovani (promastigotes, axenic amastigotes) |

Promastigotes: ED50 = 458,000 µg/mL at 72 h; Axenic amastigotes: ED50 = 6000 µg/mL at 72 h | [27][63] | |

| Seeds, Roots | Methanol extract | ND | L. tropica | Seeds: IC50 = 18.6 µg/mL; Roots: IC50 = 16.4 µg/mL |

[28][64] | |

| Plantaginaceae | ||||||

| Plantago major | Seeds | 80% Ethanol | ND | P. falciparum | IC50 = 40.0 µg/mL | [29][65] |

| Polygonaceae | ||||||

| Rumex crispus L. | Leaves, roots | Methanol and ethanol extract | ND | Trypanosoma brucei brucei | Etanol root: IC50: 9.7 μg/mL | [30][66] |

| Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 strain | Methanol leaves: IC50 = 15 μg/mL | [30][66] | ||||

| Portulacaceae | ||||||

| Portulaca oleraceae | Leaves, stems | Essential oils | Phytol, squalene, palmitic acid, ethyllinoleate, ferulic acid, linolenic acid, scopoletin, linoleic acid, rhein, apigenin, bergapten | L. major (promastigotes) | Leaves: IC50 = 360 µg/mL; Stems: IC50 = 680 µg/mL | [31][67] |

| Tetrameristaceae | ||||||

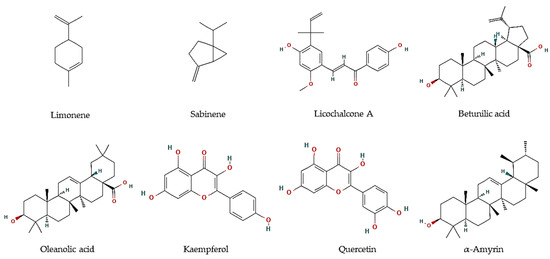

| Pelliciera rhizophorae Planch. & Triana | Leaves | Methanol:Chloroform (1:1) fraction | α-amyrin, β-amyrine, ursolic acid, oleanolic acid, betulinic acid, brugierol, iso-brugierol, kaempferol, quercetin, and quercetin | Leishmania donovani | Oleanolic acid: IC50 = 5.3 μM Kaempferol: IC50 = 22.9 μM Quercetin:IC50 = 3.4 μM |

[32][68] |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | α-Amyrin: IC50 = 19.0 μM | [32][68] | ||||

| Plasmodium falciparum | Betulinic acid: IC50 = 18.0 μM | [32][68] |

2. In Vivo Studies

| Family/Species | Plant Organ | Extract/Fraction/Compound | Chemical Components | Assay | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | ||||||

| Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants (syn. Chenopodium ambrosioides L.) | Aerial organs | Essential oils | Ascaridole, carvacrol, caryophyllene oxide | Cutaneous leishmaniasis-L. amazonensis in BALB/c mice | Prevented lesion development compared with untreated animals | [36][72] |

| Mix of ascaridole, carvacrol, caryophyllene oxide | Cutaneous leishmaniasis-L. amazonensis in BALB/c mice | Cause death of animals after 3 days of treatment | [36][72] | |||

| Leaves | Essential oil | Ascaridole | Entamoeba histolytica HM-1 in IMSS strain Golden hamsters infected with trophozoites |

8 mg/kg and 80 mg/kg reverted the infection | [16][52] | |

| Leaves | 70% Ethanol | ND | BALB/c mice infected with P. berghei | Increased survival and decreased parasitaemia | [15][51] | |

| Leaves | 70% Ethanol | ND | C3H/HePas mice infected with Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes | Reduced nitric oxide production and the parasite load | [37][73] | |

| Malvaceae | ||||||

| Althaea officinalis L. | Flowers | 80% Ethanol | ND | P. berghei infected female Swiss albino mice | Suppression of parasitemia = 62.86 %, at a dose of 400 mg/kg | [29][65] |

| Plantaginaceae | ||||||

| Plantago major L. | Seeds | 80% Ethanol | ND | P. berghei infected female Swiss albino mice | Suppression of parasitemia = 22.46 %, at a dose of 400 mg/kg | [29][65] |