Phytoestrogens are literally estrogenic substances of plant origin. Although these substances are useful for plants in many aspects, their estrogenic properties are essentially relevant to their predators. As such, phytoestrogens can be considered to be substances potentially dedicated to plant–predator interaction.

- phytoestrogens

- nutrition

- health

- cardiovascular

- isoflavones

- coumestrol

- resorcylic acid lactone

- enterolignans

- prenylflavanone

- reproduction

1. Definition and Relative Potencies

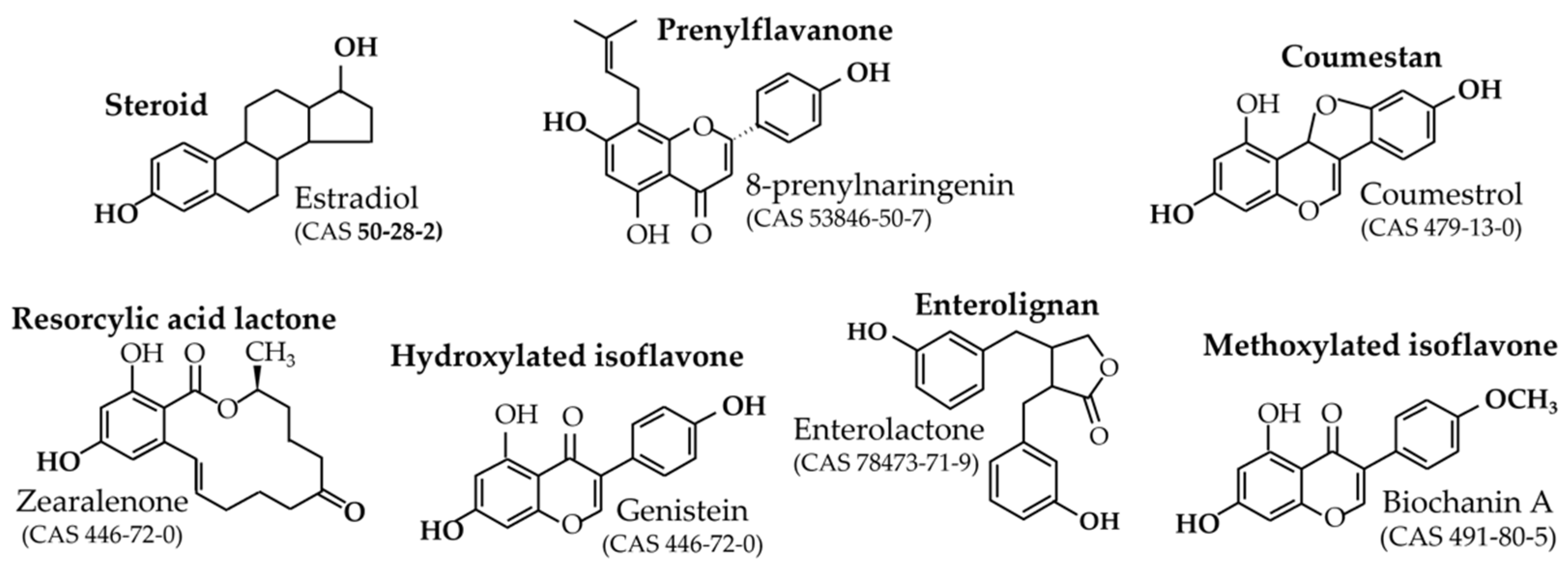

Figure 1. Chemical structures of the main phytoestrogens and their precursors beside the molecular structure of estradiol.

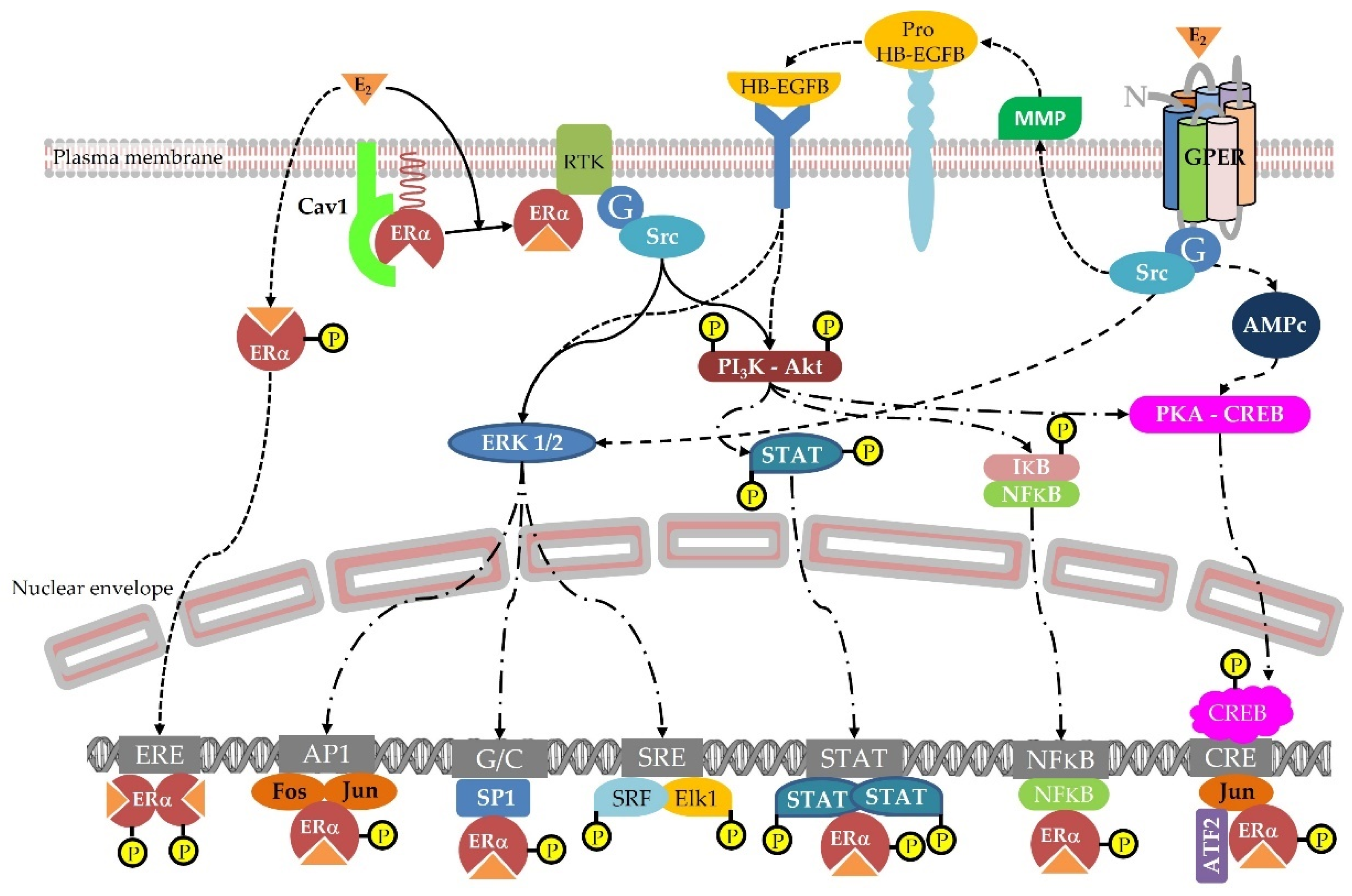

Figure 2. Cellular pathways triggered by estradiol via the nuclear ER, Membrane ER, and membrane GPER.

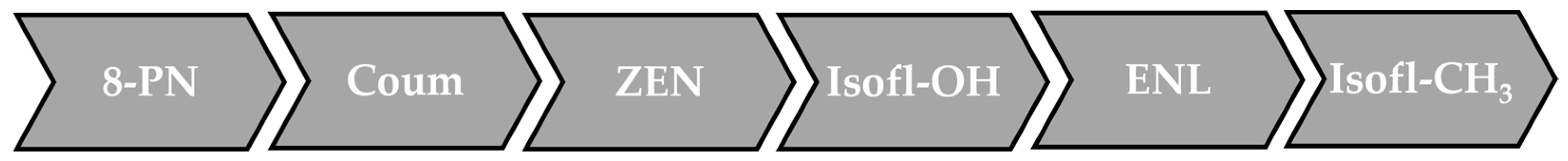

Figure 3. In vitro relative potencies of phytoestrogens. The scale does not take into account the metabolism and the bioavailability of the compounds. 8-PN: 8-prenylnaringenin; Coum: coumestrol; ZEN: zearalenone and zearalenol; Isofl-OH: hydroxylated isoflavones (C4′ position), i.e., genistein, daidzein, equol and glycitein; ENL: enterolignans, i.e., enterodiol and enterolactone; Isofl-CH3: methoxylated isoflavones (C4′ position), i.e., biochanin A and formononetin.

2. Origin and Role in Plants

- Mycotoxins;

- Phytoalexins;

- Non-estrogenic native compounds requiring gut-flora metabolism to become active.

This late category includes equol and enterolignans, which are estrogenic but are generated by the cooperation of human gut-bacteria clusters [9][10]. Given that not all consumers harbour the relevant bacteria species, these compounds will not be present and active in all consumers. The origin of their precursors can be named (and will be mentioned later), but ingesting these plant sources will never guarantee an exposure to estrogenic metabolites.

-

Prenyl-flavanones

The prenyl-flavanones 8-prenylnaringenin, 6-prenylnaringenin, and isoxanthohumol are secreted by the lupulin glands of hops’ inflorescences. Their role in plants seems to be poorly documented, while their estrogenic activities, which are essentially provided by 8-prenylnaringenin, are often cited. However, Yan et al., [11] recently reported a significant anti-fungal activity of isoxanthohumol on Botritis cinerea. This means that the prenylflavanones can act as phytoalexins in hops.

-

Coumestrol

Coumestrol is essentially produced in alfalfa, Medicago sativa (up to 36 mg/100 g Dry Mater (DM) in a Stamina 5 cultivar), and clover (14.079 mg/100 g DM), where it acts as a phytoalexin. To a lesser extent, it can also be found in mungo beans (0.932 mg/100 g DM), pinto beans (1.805 mg/100 g DM), kala chana seeds (6.130 mg/100 g DM), and in split beans (0.812 mg/100 g DM) [12]. In all cases, the pulses are considered raw, and cooking in water removes the glycosidic forms of coumestrol which are majoritarian. Such a treatment was previously used to reduce the toxic effects of alfalfa extracts on livestock reproduction [13]. In alfalfa, coumestrol is produced in response to an infestation by Pseudopeziza medicaginis or by Stemphylium vesicarium [14]. In clover, it may be present in some white clover cultivars such as Sonja, and its concentration increases when the fungus Pythium ultimum is inoculated [15]. It may also be present in soy; however, according to the literature, its presence is not systematic and may also be linked to a pathogenic fungus infestation. In clover and alfalfa, it is thought to play a role in the plant symbiosis with arbuscular mycorrhizae and rhizobium bacteria, which colonize plant roots to form nitrogen-fixing nodules [12][15].

-

Resorcylic acid lactones

The estrogenic resorcylic acid lactones are the mycotoxins zearalenone and zearalenol types α and β. All are produced by fungi of the Fusarium family and develop on maturing corn, wheat, barley, rye oats, soybeans, sorghum, peanuts, and other food and feed crops, both in the field and on grains during transportation or storage. Zearalenone and zearalenol are mainly produced by Fusarium graminearum and F. semitectum [12]. Due to its structural similarity to naturally occurring estrogens, zearalenone is an estrogenic mycotoxin that induces obvious estrogenic effects in animals [16]. Zearalenone and zearalenol productions are favoured by high-humidity and low-temperature conditions. Zearalenone is stable in food under regular cooking temperature; however, it can be reduced under intense heating. In a human diet, the main sources are grain milling products, e.g., breakfast cereals, breads, and rolls. These mycotoxins are carefully managed at harvest and human exposure remains low. Efsa monitors the zearalenone and zearalenol levels in cereals and food. A tolerable daily intake (TDI) has been fixed at 0.25 µg/kg/day. This level includes zearalenone, zearalenol, and their metabolites, i.e., their glucuro- and sulfo-conjugates.

-

Isoflavones

Isoflavones are present in several legumes at different concentrations. Soybeans, alfalfa, clover, and kudzu root (Pueraria sp.) are those containing the highest amounts of hydroxylated isoflavones or their precursors: the methoxylated isoflavones on the 4′-carbon (biochanin A and formononetin). Moreover, lentils, chickpeas, mungo beans, and broad beans contain an amount of 10 to 100 times less of isoflavones. Kudzu (Pueraria lobata or P. mirifica), a Chinese medicinal plant, also contains high amounts of genistein and daidzein in combination with puerarin. The ratio of genistein and daidzein are inverted in kudzu when compared to soy. This will be discussed later. Isoflavones also play as an attractant of arbuscular mycorrhizae and rhizobium bacteria in several pulses, including soy [12]. The contamination of a soy strain with the fungus Diaporthe phaseolorum f. sp. meridionalis induced the accumulation of isoflavones (genistein and daidzein), pterocarpans (glyceolins), and flavones (apigenin and luteolin) via the nitric oxide synthase pathway [17]. According to some authors, isoflavones also play a role as phytoalexins, preventing insect attacks in combination with UV resistance in the plant [18].

-

Enterolignans

Finally, enterolactone and enterodiol are produced from seccoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) by the gut flora of certain consumers [9]. Other lignans were shown to lead to estrogenic-enterolignan formation, namely, seccoisolariciresinol, lariciresinol, matairesinol, pinoresinol, syringaresinol, sesamin, sesamolin, and medioresinol [12]. Lignans are considered moieties of lignin, whose role is to provide a rigid structure to many plants, including cereals. These compounds are also present in seeds. Although lignans are known to be present in fruits and vegetables, the main source of SDG is known to be linseeds, also called flaxseeds [19].

- 3. Aromatic and Medicinal Plants

Certain aromatic or medicinal plants (herbal teas or essential oils) also exert endocrine effects, in particular on metabolic functions and reproductive functions. In 1975, Farnsworth reported a long list of plants that had long been used in Western countries as anti-fertility agents [20][21], and 60% of them contained phytoestrogens, isoflavone-type phytoestrogens, or coumestrol. Experimental studies have identified preovulatory, pre-implantation, and post-implantation anti-fertility mechanisms induced by other plant substances affecting the hypothalamic–pituitary and female reproductive organs. Lithospermic acid, m-xylohydroquinone, coronaridine, rutin, and rottlerin also have anti-fertility properties [20][21]. However, certain volatile oils, such as quinine, castor oil, and sparteine, are considered abortifacients with toxic side effects on the foetus independent of an estrogenic mechanism [20][21][22]. Contraceptive plants contain terpenoids, alkaloids, glycosides, phenols, and other compounds which interfere with sex receptors or steroid hormones. Not all mechanisms are related to an estrogen-type mechanism; some are related to an anti-androgen-type effect. Many of them (Polygonum hydropiper Linn, Citrus limonum, Piper nigrum Linn, Juniperis communis, Achyanthes aspera, Azadirachta indica, Tinospora cordifolia, and Barleria prionitis) act by an anti-zygotic mechanism [23]. As an example, the contraceptive properties of the neem leaf oil (Azadirachta indica) is due to an estrogenic compound, Azadirachtin A [24], and an anti-androgenic compound that disrupts spermatogenesis in men [25].

- Medicinal plants displaying estrogenic effects are used in the treatment of acute menopausal syndrome: mainly hot flushes, insomnia, vaginal atrophy, and osteoporosis, [26][27] but also mood and anxiety [28]. Estrogenic effects of aromatic or medicinal plants have often been established in clinical observations and demonstrated experimentally on the basis of plant extracts [29][30]. Therefore, further studies are required to reinforce data about their bioactive compounds beyond isoflavones, lignans, and coumestans. Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum), lemon balm (Melissa officinalis), sage (Salvia officinalis), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), and even black cohosh (Cimifiga racemosa) owe their estrogenic effects to polyphenols or terpenes. Thus, sage (Saltiva officinalis), traditionally used to suppress hot flushes and stimulate cognitive faculties in postmenopausal women, owes its effects to a glycosylated flavonoid (luteoline-7_0-glycoside) also found in other medicinal or aromatic plants (such as oregano, chasteberry Vitex rotundifolia, and Vitex Agnus-castus). The estrogenicity of terpenes and terpenoids is mediated through alpha estrogen receptors, but it is still poorly investigated [31][32]. Plants containing estrogenic terpenes and terpenoids are also used in traditional medicine in the treatment and prevention of hormonal cancers and in food supplements to correct the symptoms of menopause and/or prevent cardiovascular, immunological and/or inflammatory disorders. These molecules are particularly concentrated in the essential oils of medicinal plants including clary sage, peppermint, chamomile, and niaouli [33][34]. A recent in vitro study, having examined the estrogenic potency of several medicinal plants by using a human placenta model, points to anethole as one of the most estrogenic molecules [35]. Anethole is a phenylpropene that confers estrogenic effects to fennel and other Apiaceous plants (such as star anise and cumin) that are widely present in traditional medicine or have culinary uses in many countries as spices or seed teas; they are used for their beneficial effects on digestion, intestinal spasms, and premenstrual symptoms, or to stimulate lactation.

- Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) deserves special attention because of its growing consumption in different forms around the world (as a vegetable, herbal tea, or in supplements). Beneficial effects on menopausal syndrome have been established by a clinical study conducted in Iran on ninety postmenopausal women (45–60 years old): a twice-daily intake of fennel (2 × 100 mg, n = 45) for four weeks was sufficient to reduce symptoms of menopause (hot flushes, fatigue, sleep disturbances, vaginal dryness, anxiety, and irritability) vs. the placebo group (n = 45) [36]. On the other hand, a regular intake of fennel seed teas in early age in order to soothe intestinal spams occurring in babies may be a cause of premature thelarche or could advance the age of puberty in young girls [37][38][39].

- Although the data relating to these plants and the molecules they contain have been expanding in recent years, they are still too incomplete or controversial to allow quantitative indications to be drawn. For this reason, this research will not focus on the phytoestrogens conveyed by medicinal plants. Nevertheless, due to their use as ingredients in nutritional supplements, the reader should be warned that the regular intake of these plants, and particularly at high dosages via dietary supplements, may lead to similar or even superior effects to those induced by the dietary intake of phytoestrogens and hence their therapeutic use [26][40][41].

Medicinal plants displaying estrogenic effects are used in the treatment of acute menopausal syndrome: mainly hot flushes, insomnia, vaginal atrophy, and osteoporosis, [26][27] but also mood and anxiety [28]. Estrogenic effects of aromatic or medicinal plants have often been established in clinical observations and demonstrated experimentally on the basis of plant extracts [29][30]. Therefore, further studies are required to reinforce data about their bioactive compounds beyond isoflavones, lignans, and coumestans. Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum), lemon balm (Melissa officinalis), sage (Salvia officinalis), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), and even black cohosh (Cimifiga racemosa) owe their estrogenic effects to polyphenols or terpenes. Thus, sage (Saltiva officinalis), traditionally used to suppress hot flushes and stimulate cognitive faculties in postmenopausal women, owes its effects to a glycosylated flavonoid (luteoline-7_0-glycoside) also found in other medicinal or aromatic plants (such as oregano, chasteberry Vitex rotundifolia, and Vitex Agnus-castus). The estrogenicity of terpenes and terpenoids is mediated through alpha estrogen receptors, but it is still poorly investigated [31][32]. Plants containing estrogenic terpenes and terpenoids are also used in traditional medicine in the treatment and prevention of hormonal cancers and in food supplements to correct the symptoms of menopause and/or prevent cardiovascular, immunological and/or inflammatory disorders. These molecules are particularly concentrated in the essential oils of medicinal plants including clary sage, peppermint, chamomile, and niaouli [33][34]. A recent in vitro study, having examined the estrogenic potency of several medicinal plants by using a human placenta model, points to anethole as one of the most estrogenic molecules [35]. Anethole is a phenylpropene that confers estrogenic effects to fennel and other Apiaceous plants (such as star anise and cumin) that are widely present in traditional medicine or have culinary uses in many countries as spices or seed teas; they are used for their beneficial effects on digestion, intestinal spasms, and premenstrual symptoms, or to stimulate lactation.

Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) deserves special attention because of its growing consumption in different forms around the world (as a vegetable, herbal tea, or in supplements). Beneficial effects on menopausal syndrome have been established by a clinical study conducted in Iran on ninety postmenopausal women (45–60 years old): a twice-daily intake of fennel (2 × 100 mg, n = 45) for four weeks was sufficient to reduce symptoms of menopause (hot flushes, fatigue, sleep disturbances, vaginal dryness, anxiety, and irritability) vs. the placebo group (n = 45) [36]. On the other hand, a regular intake of fennel seed teas in early age in order to soothe intestinal spams occurring in babies may be a cause of premature thelarche or could advance the age of puberty in young girls [37][38][39].

Although the data relating to these plants and the molecules they contain have been expanding in recent years, they are still too incomplete or controversial to allow quantitative indications to be drawn. For this reason, this research will not focus on the phytoestrogens conveyed by medicinal plants. Nevertheless, due to their use as ingredients in dietary supplements, the reader should be warned that the regular intake of these plants, and particularly at high dosages via food supplements, may lead to similar or even superior effects to those induced by the dietary intake of phytoestrogens and hence their therapeutic use [26][40][41].

References

- Pike, A.C.; Brzozowski, A.M.; Hubbard, R.E.; Bonn, T.; Thorsell, A.G.; Engström, O.; Ljunggren, J.; Gustafsson, J.A.; Carlquist, M. Structure of the ligand-binding domain of oestrogen receptor beta in the presence of a partial agonist and a full antagonist. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 4608–4618.

- May, F.E.B. Novel drugs that target the estrogen-related receptor alpha: Their therapeutic potential in breast cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2014, 6, 225–252.

- Adlanmerini, M.; Solinhac, R.; Abot, A.; Fabre, A.; Raymond-Letron, I. Mutation of the palmitoylation site of estrogen receptor α in vivo reveals tissue-specific roles for membrane versus nuclear actions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E283–E290.

- Arnal, J.-F.; Lenfant, F.; Metivier, R.; Flouriot, G.; Henrion, D.; Adlanmerini, M.; Fontaine, C.; Gourdy, P.; Chambon, P.; Katzenellenbogen, B.; et al. Membrane and nuclear estrogen receptor alpha actions: From tissue specificity to medical implications. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 1045–1087.

- Qiu, Y.A.; Xiong, J.; Yu, T. Role of G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor in Digestive System Carcinomas: A Minireview. OncoTargets Ther. 2021, 14, 2611–2622.

- Bennetau-Pelissero, C.; Breton, B.; Bennetau, B.; Corraze, G. Effect of genistein-enriched diets on the endocrine process of gametogenesis and on reproduction efficiency of the rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2001, 121, 173–187.

- Dolinoy, D.C.; Weidman, J.R.; Waterland, R.A.; Jirtle, R.L. Maternal genistein alters coat color and protects Avy mouse offspring from obesity by modifying the fetal epigenome. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 567–572.

- Wang, Z.; Chen, H. Genistein increases gene expression by demethylation of WNT5a promoter in colon cancer cell line SW1116. Anticancer Res. 2010, 30, 4537–4545.

- Clavel, T.; Lippman, R.; Gavini, F.; Doré, J.; Blaut, M. Clostridium saccharogumia sp. nov. and Lactonifactor longoviformis gen. nov., sp. nov., two novel human faecal bacteria involved in the conversion of the dietary phytoestrogen secoisolariciresinol diglucoside. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 30, 16–26.

- Schröder, C.; Matthies, A.; Engst, W.; Blaut, M.; Braune, A. Identification and expression of genes involved in the conversion of daidzein and genistein by the equol-forming bacterium Slackia isoflavoniconvertens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 3494–3502.

- Yan, Y.-F.; Wu, T.-L.; Du, S.-S.; Wu, Z.-R. The Antifungal Mechanism of Isoxanthohumol from Humulus lupulus Linn. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10853.

- Bennetau-Pelissero, C. Natural Estrogenic Substances, Origins, and Effects. In Bioactive Molecules in Food; Mérillon, J.M., Ramawat, K., Eds.; Reference Series in Phytochemistry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018.

- Knuckles, B.E.; deFremery, D.; Kohler, G.O. Coumestrol content of fractions obtained during wet processing of alfalfa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1976, 24, 1177–1180.

- Fields, R.L.; Barrell, G.K.; Gash, A.; Zhao, J.; Moot, D.J. Alfalfa Coumestrol Content in Response to Development Stage, Fungi, Aphids, and Cultivar. Crop Ecol. Physiol. 2018, 110, 910–921.

- Carlsen, S.C.K.; Understrup, A.; Fomsgaard, I.S.; Mortensen, A.G.; Ravnskov, S. Flavonoids in roots of white clover: Interaction of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and a pathogenic fungus. Plant Soil 2008, 302, 33–43.

- Schoevers, E.J.; Santos, R.R.; Colenbrander, B.; Fink-Gremmels, J.; Roelen, B.A. Transgenerational toxicity of Zearalenone in pigs. Reprod Toxicol. 2012, 34, 110–119.

- Modolo, L.V.; Cunha, F.Q.; Braga, M.R.; Salgado, I. Nitric oxide synthase-mediated phytoalexin accumulation in soybean cotyledons in response to the Diaporthe phaseolorum f. sp. meridionalis elicitor. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 1288–1297.

- Zavala, J.A.; Mazza, C.A.; Dillon, F.M.; Chludil, H.D.; Ballaré, C.L. Soybean resistance to stink bugs (Nezara viridula and Piezodorus guildinii) increases with exposure to solar UV-B radiation and correlates with isoflavonoid content in pods under field conditions. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 920–928.

- Setchell, K.D.; Brown, N.M.; Zimmer-Nechemias, L.; Wolfe, B.; Jha, P.; Heubi, J.E. Metabolism of secoisolariciresinol-diglycoside the dietary precursor to the intestinally derived lignan enterolactone in humans. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 491–501.

- Farnsworth, N.R.; Bingel, A.S.; Cordell, G.A.; Crane, F.A.; Fong, H.H.S. Potential value of plants as sources of new antifertility agents I. J. Pharm. Sci. 1975, 64, 535–598.

- Farnsworth, N.R.; Bingel, A.S.; Cordell, G.A.; Crane, F.A.; Fong, H.H.S. Potential value of plants as sources of new antifertility agents II. J. Pharm. Sci. 1975, 64, 717–754.

- Farnsworth, N.R.; Akerele, O.; Bingel, A.S.; Soejarto, D.D.; Guo, Z. Medicinal plants in therapy. Bull. World Health Organ. 1985, 63, 965–981.

- Daniyal, M.; Akram, M. Antifertility activity of medicinal plants. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2015, 78, 382–388.

- Kushwaha, P.; Ahmad, N.; Dhar, Y.V.; Verma, A. Estrogen receptor activation in response to Azadirachtin A stimulates osteoblast differentiation and bone formation in mice. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 23719–23735.

- Patil, S.M.; Shirahatti, P.S.; Chandana Kumari, V.B.; Ramu, R.; Nagendra Prasad, M.N. Azadirachta indica A. Juss (neem) as a contraceptive: An evidence-based review on its pharmacological efficiency. Phytomedicine 2021, 88, 153596.

- Kargozar, R.; Azizi, H.; Salari, R. A review of effective herbal medicines in controlling menopausal symptoms. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 5826–5833.

- Słupski, W.; Jawień, P.; Nowak, B. Botanicals in Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1609.

- Shahmohammadi, A.; Ramezanpour, N.; Mahdavi Siuki, M.; Dizavandi, F.; Ghazanfarpour, M.; Rahmani, Y.; Tahajjodi, R.; Babakhanian, M. The efficacy of herbal medicines on anxiety and depression in peri- and postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Post Reprod. Health 2019, 25, 131–141.

- Zava, D.T.; Dollbaum, C.M.; Blen, M. Estrogen and progestin bioactivity of foods, herbs, and spices. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1998, 217, 369–378.

- Liu, J.; Burdette, J.E.; Xu, H.; Gu, C.; van Breemen, R.B.; Bhat, K.P.; Booth, N.; Constantinou, A.I.; Pezzuto, J.M.; Fong, H.H. Evaluation of estrogenic activity of plant extracts for the potential treatment of menopausal symptoms. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 2472–2479.

- Kiyam, R. Estrogenic terpenes and terpenoids: Pathways, functions and applications. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 815, 405–415.

- Oerter Klein, K.; Janfaza, M.; Wong, J.A.; Chang, R.J. Estrogen bioactivity in fo-ti and other herbs used for their estrogen-like effects as determined by a recombinant cell bioassay. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 4077–4079.

- Howes, M.-J.R.; Houghton, P.J.; Barlow, D.J.; Pocock, V.J.; Milligan, S.R. Assessment of estrogenic activity in some common essential oil constituents. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2002, 54, 1521–1528.

- Contini, A.; di Belle, D.; Azzarà, A.; Giovanelli, S.; D’Urso, G.; Piaggi, S.; Pinto, B.; Pistelli, L.; Scarpato, R.; Testi, S. Assessing the cytotoxic/genotoxic activity and estrogenic/antiestrogenic potential of essential oils from seven aromatic plants. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 138, 111205.

- Fouyet, S.; Olivier, E.; Leproux, P.; Dutot, M.; Rat, P. Evaluation of Placental Toxicity of Five Essential Oils and Their Potential Endocrine-Disrupting Effects. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 2794–2810.

- Rahimikian, F.; Rahimi, R.; Golzareh, P.; Bekhradi, R.; Mehran, A. Effect of Foeniculum vulgare Mill. (fennel) on menopausal symptoms in postmenopausal women: A randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Menopause 2017, 24, 1017–1021.

- Türkyilmaz, Z.; Karabulut, R.; Sönmez, K.; Can Başaklar, A. A striking and frequent cause of premature thelarche in children: Foeniculum vulgare. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2008, 43, 2109–2111.

- Rahimi, R.; Ardekani, M.R. Medicinal properties of Foeniculum vulgare Mill. in traditional Iranian medicine and modern phytotherapy. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2013, 19, 73–79.

- Okdemir, D.; Hatipoglu, N.; Kurtoglu, S.; Akın, L.; Kendirci, M. Premature thelarche related to fennel tea consumption? J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 27, 175–179.

- Sheehan, D.M. Herbal medicines, phytoestrogens and toxicity: Risk: Benefit considerations. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1998, 217, 379–385.

- Kristanc, L.; Kreft, S. European medicinal and edible plants associated with subacute and chronic toxicity part I: Plants with carcinogenic, teratogenic and endocrine-disrupting effects. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 92, 150–164.