Mechanically oresponsive smart windows have thepresent advantages of simple constructureion, low cost and good, and excellent stability.

- energy saving

- smart window

- mechanoresponsive

- driving mode

1. Introduction

2. Structures of Mechanoresponsive Smart Windows

Ove

Mechanical strain driven by mechanical force, electricity, humidity, etc., reconfigures the surface morphology or changes the interface structure, thus changing the optical transmittance by modulating the scattering or diffraction of lights. Based on the types of surface morphology or interface structure to achieve optical modulation, we created six primary categories of mechanoresponsive materials: micro/nano-array, wrinkling, crack, novel interface, tunable interface parameter, and the surface–interface synergy effect. For each category, we focus on the latest developments in the mechanisms and optical tunable properties.2.1. Mechanoresponsive Smart Windows Based on Micro/Nano-Array

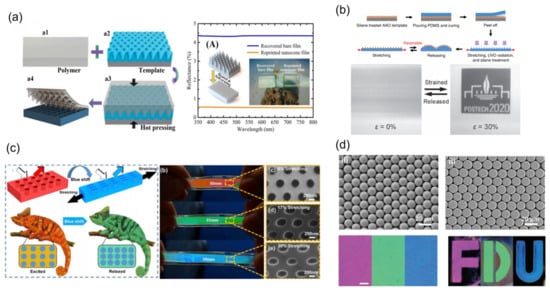

Surfaces periodic nanoscale or microscale arrays have attracted attention as a new type of smart windows material, because of their special advantages, such as flexible light trapping property, broadband antireflection, easy preparation, and high surface area. To date, several nanoarrays have been designed and fabricated, such as nanocones [13], nanopillars [14,15,16], nanoholes [17,18], nanospheres [19]. These structures can change their optical performance by dynamically modulating surface geometry in response to various external stimuli. In recent years, Li et al. reported a self-erasable nanocone antireflection film via a simple surface replication method (Figurview of mechan 1a) [20]. The nanocone arrays with constant heights and periods can be easily formed in the shape memory polymer film of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and are conveniently erased by thermal irritation. In the initial state, the PVA film with shape memory effect shows 0.6% reflectivity in the visible spectral, and the reflectivity of self-erasable PVA film can be switched from 0.6% to 4.5% by adjusting the temperature (>80 °C). Benefiting from PVA’s shape memory effect, the reflectivity over the visible spectral range of the self-erasable antireflection membrane can be changed. Lee et al. presented a simple manufacturing of stretchable smart windows with the surface morphology pattern consisting of nanopillar arrays on the wrinkled poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) film [21]. As shown in Fically guresponsive smart we 1b, in released state, because of the wide scattering of light via the periodic micrometer size surface structures, the PDMS films show optically opaque properties, which have a frosted glass-like appearance.

an

d dr

CHENure Bo1, Q1

c, the stretchable nanohole photonic crystals are prepared by nanoimprint technology. The compound film with shape memory function is prepared via using shape memory alloy (SMA) and PDMS materials. The function of SMA is to make the nanohole photonic crystal deform under the electrical stimulation and the function of PDMS is to make the SMA restore its initial shape after taking off the electrical stimulation. Under the voltage of 1.0–1.5 V, the compound film can achieve color changing over the whole visible light range, and the total deformation required is only less than 30%. Ji et al. reported a nanospheres shape memory retro-reflective structural color film that originated from the mechanisms of retro-reflection and thin-film interference combined with the internal reflection (Figure 1d). During the deformation process, due to the change in nanospheres shape, the structural color of the optical film gradually disappears [23]. Moreover, this film displays excellent repeat and rewrite ability, which structural color can be recovered by heating. In summary, micro/nano-array-based mechanoresponsive smart windows can adjust color or transparency as the tunable array shape or array numbers simply. However, their optical modulation is limited, because conventional micro/nano arrays are difficult to disappear completely in the process of deformation.2.2. Mechanoresponsive Smart Windows Based on Wrinkling

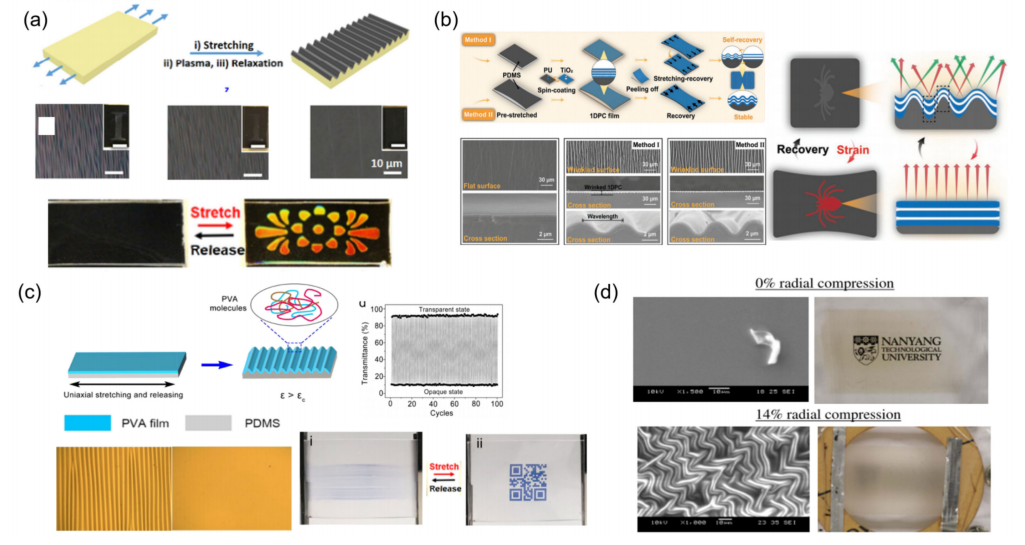

As a universal pattern in nature, wrinkling is another typical surface texture that can dynamically be tuned by mechanical strains and has been extensively explored for optical devices, stretchable electronics, energy storage devices, etc. [24,25,26]. Depending on the incident angles, the wrinkled surface refracts the incident light to different directions and blurs the objects behind the wrinkled thin layer/substrate film. However, when the wrinkles are erased by lateral tensile strains, the light beams can pass through the film with reduced deflection, changing the film from opaque to translucent or to highly transparent [27,28]. In recent years, researchers have designed a variety of surface wrinkled smart window materials. InFenig2 , Liu Wreiwei1 , L2

a, Li et al. reported a notable thickness-dependent wrinkling behavior of PDMS films via using the typical plasma-stretch processes [29]. They have showed brilliant surface structural colors and pre-designed colorimetric responses to mechanical strain on plasma-treated PDMS films by changing the substrate thickness. Because of the high orderliness and considerable small size of the wrinkles, uniform, bright, and angle-dependent structural colors can be obtained on thick PDMS films (>1 mm).

an

1. Introduction

2.3. Mechanoresponsive Smart Windows Based on Cracks

As the energy crisis continues to have its effects, the energy crunch around the world has further intensified. In addition, with the increase in extreme weather caused by global warming, the development of science and technology to slow down global warming is also becoming a trend. Therefore, energy conservation is advocated by all countries. In developed countries, it is reported that building energy use accounts for 30-40% of total energy consumption [1,2], exceeding the amount of industry or transport. About 47% of energy for building services comes from heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems [3,4]. As the main way of indoor and outdoor heat exchange, energy consumption through windows accounts for a large proportion. In China, 400 million to 600 million square meters of windows are installed every year, more than the United States and European countries combined. Therefore, designing smart windows that can dynamically adjust the light transmittance is considered an effective way to save energy [5-7]. In addition to building energy efficiency, this technology has also generated widespread interest in cars, greenhouses and sunglasses, among others.

In addition to optical property modulation by changing the structural parameters such as the number and micro/nano-pattern spacing on the surface, optical pathway opening/closing or the appearance/disappearance of scattered light units by changing the opening/closing state of micro cracks is also an effective means to achieve rapid excitation of fluorescence or rapid decrease of transmittance [33]. Because of the weak binding at the fracture, it usually has highly sensitive properties. Both microscale and nanoscale structural designs have well demonstrated their opportunity in achieving excellent dynamic optical performance. By means of stretching/releasing and revealing/concealing patterns, micro/nanoscale cracks enable tune a series of reversible adaptive optics, e.g., transparency, fluorescent color, and luminescent intensity.Sunlight radiant heat at visible and near-infrared wavelengths accounts for about 44% and 47% of the total radiated heat, respectively. Under external stimuli, smart windows can reversibly adjust the light reflectivity or transmittance of visible or near-infrared wavelengths [8]. Lambert et al. proposed in the 1980s [9] that smart windows based on electrochromic materials are the most attractive type and the most widely used. It usually presents a sandwich structure with a functional material layer between two transparent electrodes. The optical properties are adjustable due to the properties of re-dox reaction or ion intercalation/separation under an electric field[10]. Thermochromic materials can change color with temperature due to thermal decomposition or geometric conformational changes [11]. When exposed to specific wavelengths of light, photochromic materials change color due to chemical bond homogenization reactions or circumcyclic reactions [12]. Although extensive research has been conducted in electrochromics, thermochromics, and photochromic smart windows, their fabrication and construction are quite complex, requiring external fields to achieve light modulation, limiting the commercialization of these materials. In recent years, mechanically responsive smart windows through simple mechanical strain adjustment have attracted more and more attention. Typically, the surface topography or internal structure of a mechanically responsive material is deformed or reconfigured due to mechanical strain, resulting in a change in light transmittance or color through light scattering or diffraction. Therefore, no external power supply is usually required for control, making mass production cost-effective. In addition, the optical properties of mecharomatic materials can be adjusted even at very small strains (i.e. ~10%). In contrast, electrochromic, photochromic or thermochromic smart windows typically require more time to respond. For example, electrochromic WO3The coloring/bleaching time of the film is 1~6 s. The response time of poly(N-thiopropyl acrylonide) (PNIPAm)-based films based on thermochromic is 40~120 seconds. Inorganic photochromic films have a wide range of response times, ranging from 0.1 seconds to hundreds of seconds.

This paper reviews the latest progress of mechanical chromic intelligent temperature channels. Based on the surface/interface mechanism, we discuss strategies for all six types of mechanical chromic smart windows. The most common mode of driving for mechanical strain is mechanical force, i.e. changing surface/interface morphology by stretching, compressing, rotating, etc. Here, we also summarize six unconventional drive modes that generate mechanical strain and discuss their advantages and disadvantages. Finally, it offers future developments for potential applications for mechanically responsive smart windows.

2. Th

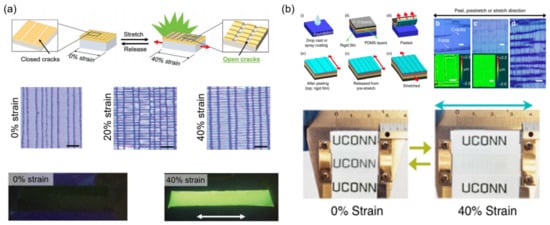

Mao et al. reported a simple and highly effective method of mechanochromic materials based on a bilayer structure. This structure is composed of a sputter-coated light-shielding metal layer (Au/Pd) on a PDMS bottom substrate containing the fluorescent dye [34], featuring horizontal and/or vertical micro-scale cracks under stretched material (Figure struct3a). The width of cracks opening on the metal light-shielding layer under stretching/releasing endows the UV radiation to stimulate the fluorescent dye, which can exhibit luminescent color embed in the PDMS matrix. The crack opening width can be well tuned via applying different degrees of pre-stretching strain in the preparation process, leading to customizable mechanochromic responses. High sensitivity and excellent durability of the devices are also displayed, which can exhibit great mechanochromic properties after 500 cycles of tensile and release. Zeng et al. introduced a thin rigid composite material film, which was prepared by drop-casting method or spray-coating on the plastic substrate subsequent to the treatment of vinyl-functionalized silane vapor [35]. The surface morphology of the rigid film showed periodical longitudinal cracks which are vertical to the peeling direction and the transverse wrinkles perpendicular to the cracks because of the compressive force originating from the Poisson effect. In the released state, this film shows >88% transmittance at 600 nm and the film becomes highly opaque (transmittance < 29%) under 40% strain (Figure of a mechan3b).

art window

Mechanical strain driven by mechanical force, electricity, humidity, etc., reconfigures the surface topography or changes the interface structure, thereby changing the optical transmittance by modulating the scattering or diffraction of light. Based on the type of surface topography or interface structure that achieves light modulation, we have created six broad classes of mechanically responsive materials: micro/nano arrays, wrinkles, cracks, novel interfaces, tunable interface parameters, and surface-interface synergies. For each category, we focus on the latest developments in mechanism and optically adjustable characteristics.

2.4. Novel Interface-Introduced Mechanoresponsive Smart Windows

2.1. Smart window of mechanical response based on micro/nano arrays

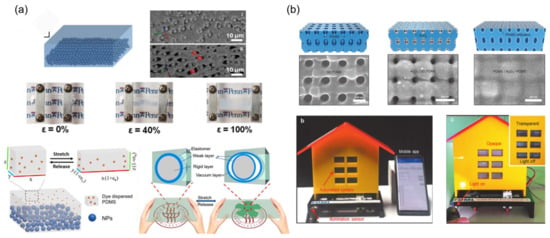

Similar to the surface structure, the interface structure can also dynamically regulate the scattering and interference of light, thus achieving the optical modulation. Moreover, the mechanoresponsive materials based on interface structure regulation can overcome the problem that the surface structure is susceptible to failure by external environment (such as dust, moisture, mechanical load, etc.), and show stronger controllability and stability [36,37]. Based on this, materials that achieve light transmission regulation through dynamic generation/disappearance of novel interfaces have been widely investigated.As a new type of smart window material, surface periodic nanoscale or microscale array has attracted much attention because of its special advantages such as flexible light capture, broadband anti-reflection, easy preparation, and high specific surface area. To date, several nanoarrays have been designed and fabricated, such as nanocones [13], nanopillars [14-16], nanopores [17, 18], nanospheres [19]. These structures can change their optical properties by dynamically modulating the surface geometry in response to various external stimuli.

In recent years, Li et al. have reported a self-erasing nanocone antireflection coating by a simple surface replication method (Figure 1a) [20]. Nanocone arrays with constant height and cycle can easily form shape memory polymer films of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and can be easily erased by thermal stimulation. In its initial state, PVA films with shape memory effects exhibit 0.6% reflectivity in the visible spectrum by adjusting the temperature (>80).orThanks to the shape memory effect of PVA, the reflectivity of the self-erasing anti-reflective coating in the visible spectral range can be changed. Lee et al. propose a simple fabrication of a retractable smart window with a surface morphological pattern consisting of a nanopillar array on a crumpled poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) film [21]. As shown in Figure 1b, in the released state, PDMS films exhibit optically opaque properties with a frosted glass-like appearance due to the extensive scattering of light through periodic micron-sized surface structures.

Figure 1 Strategies for Mechanical Response Smart Window Based on Nanoarrays: (a) Nanocones [20] Copyright 2018, MDPI (Basel, Switzerland), (b) Nanopillars [21] Copyright 2010, John Wiley & Sons (Hoboken, New Jersey, USA), (c) Nanopores [22] Copyright 2019, Elsevier (Amsterdam, Netherlands), (d) Nanospheres [23] Copyright 2021, John Wiley & Sons.

4a, Shu Yang’s group and our group firstly proposed the approach to prepare smart window film by combining the nanoparticle arrays with similar refractive indices to elastomers [38]. During the stretching process, a large number of micro/nano-optical interfaces were generated because of the mismatch between the modulus of the soft elastomer and the rigid nanoparticles, which result in a significant decrease in the light transmission of the film. Although the transmittance of this film is up to 70%, it still improves the mechano-optical sensitivity. Therefore, constructing fast-responsive interfaces through the generating/vanishment of scattering under mechanical strain, is an easy and effective way to improve sensitivity. Based on this theory, our group reported an ultrasensitive dynamic optical membrane based on the dye-induced weak boundary layer [39]. This sample exhibits a dramatic decrease in transmittance by 44% at very small strain (15%). Moreover, a total dynamic transmittance rate of ~75% is demonstrated, while this membrane can be reversibly modulated for more than 2000 cycles with stable structural integrity and optical performance.At 30% mechanical stretching, the film becomes optically transparent due to the absence of wrinkles with a transmittance of up to 95%. Inspired by chameleons, which can adjust colors according to the environment, Zhao et al. designed a surface nanoporous color display film [22]. As shown in Figure 1c, stretchable nanohole photonic crystals were prepared using nanoimprinting technology. Shape memory alloy (SMA) and PDMS materials were used to prepare composite membranes with shape memory function. The function of SMA is to deform nanohole photonic crystals under electrical stimulation, and the function of PDMS is to restore SMA to its initial shape after shedding electrical stimulation. At voltages of 1.0-1.5 V, the composite film can achieve color change over the entire visible light range, and the total deformation required is only less than 30%. Ji et al. report a nanospheroid shape memory mirror reflective structure colored film that originates from the mechanism of retroreflection and thin film interference binding to internal reflection (Figure 1d). During deformation, the structural color of the optical film gradually disappears due to the change in the shape of the nanospheres [23]. In addition, the film has excellent repeatability and rewrite ability, and its structural color can be restored by heating. In summary, micro/nano array-based mechanical response smart windows can simply adjust color or transparency because the array shape or array number can be adjusted. However, their light modulation is limited because traditional micro/nano arrays are difficult to work with

deformation.

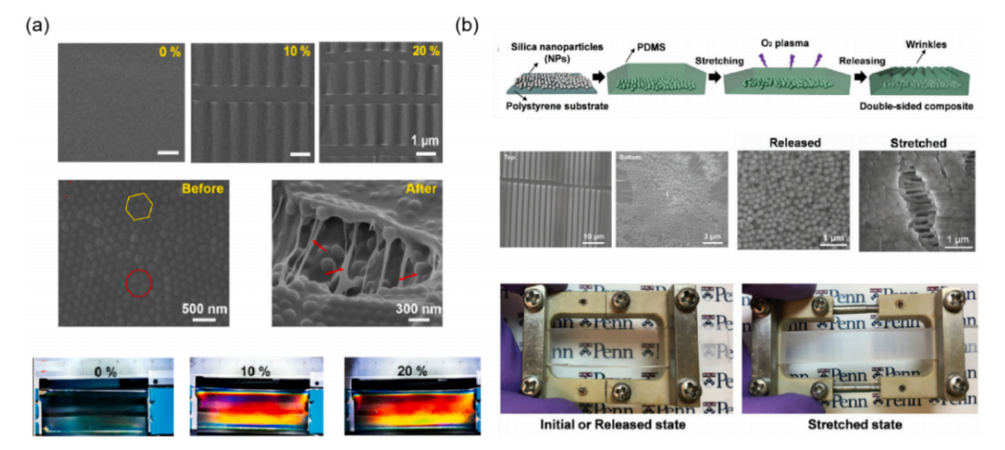

2.2. Mechanoresponsive Smart Windows Based on Wrinkling

As a universal pattern in nature, wrinkling is another typical surface texture that can dynamically be tuned by mechanical strains and has been extensively explored for optical devices, stretchable electronics, energy storage devices, etc. [24–26]. Depending on the incident angles, the wrinkled surface refracts the incident light to different directions and blurs the objects behind the wrinkled thin layer/substrate film. However, when the wrinkles are erased by lateral tensile strains, the light beams can pass through the film with reduced deflection, changing the film from opaque to translucent or to highly transparent [27,28].

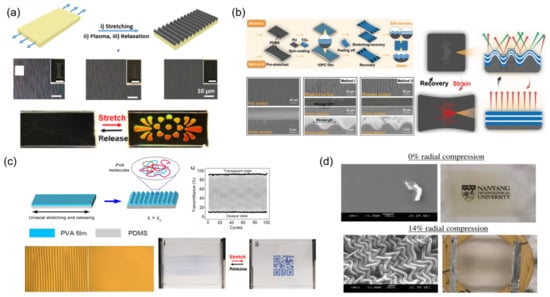

In recent years, researchers have designed a variety of surface wrinkled smart window materials. In Figure 2a, Li et al. reported a notable thickness-dependent wrinkling behavior of PDMS films via using the typical plasma-stretch processes [29]. They have showed brilliant surface structural colors and pre-designed colorimetric responses to mechanical strain on plasma-treated PDMS films by changing the substrate thickness. Because of the high orderliness and considerable small size of the wrinkles, uniform, bright, and angle-dependent structural colors can be obtained on thick PDMS films (>1 mm).

Figure 24. The strategies of mechanoresponsive smart windows based on wrinkling: (a) stretching to form wrinkles [29] Copyright 2020, Springer Nature (Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany), (b) wrinkled pho-tonic elastomer structure [30] Copyright 2022, John Wiley and Sons, (c) double-layer film wrinkle [31] Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society (Washington, DC, USA) (d) biaxial compression to form wrinkles [32] Reprinted with permission Copyright 2016, Optical Society America (Washington, DC, USA).

To eliminate the angle dependence of the structural color, inspired by a kind of bright blue luminescence spider, Lin et al. reported a new wrinkle-based photonic elastomer structure [30]. Through wrinkling stretchable 1D photonic crystals (1D PC), the photonic elastomers film with omnidirectional angle-independent brilliant structural colors are achieved (Figure 2b). They used stretchable polyurethane and nanoscale TiO2 as the raw materials by the method of alternating assembly to fabricate 1D PC as the surface structural color layer, and PDMS as the bottom elastic layer which enables the discoloration response of elastomers to wrinkles with clear boundaries. The wrinkle-based structural color and photonic structure can remain stable after 1000 tensile cycles, and mechanochromic sen-sitivity up to 3.25 nm/%. More importantly, through comprehensively controlling the lattice spacing of photonic films and micro-wrinkle structure, the structural color can realize delayed discoloration and reversible switching performance only by a single strain direction. As shown in Figure 2c, Jing et al. reported an effective strategy to preparing temperature and moisture dual-responsive surface wrinkles based on the PVA/PDMS bilayer film, which can be achieved by the rational design of modulus changing PVA skin layer on elastomer film upon moisture and temperature [31]. The bilayer film systems show remarkable advances in a fast response system, outstanding reversibility, stability, and high light transmittance modulation. Compared to the examples of uniaxial strain to form wrinkles, the biaxial compression can generate more complex 2D surface wrinkling patterns, which could be ordered or disordered. The 2D wrinkling patterns have greater interactions with lights and result in a lower transmittance. In Figure 2d, Shrestha et al. displayed a flat ZnO thin film which can be deposited on a pre-stretched elastomer mem-brane acrylic elastomer membrane by the electron beam evaporation technique [32]. This optical tunable window film appears reversible and adjustable between translucent and transparent states. When compression is not applied to a flat surface, the film is transparent with a 93% transmittance at a wavelength of 550 nm. At 14% radial compression, the film appears to surface wrinkle and has a translucent appearance, which has a very low 3% in-line transmittance. Analysis shows that both the large amplitude and the small wavelength of transparent micro-wrinkles are in favor of refracting light diffusely.

Cho et al. reported a new type of 3D nanoscale composite film, consisting of an ultrathin Al2O3 nanoshell [40]. Regardless of the stretching direction, a large amount of light-scattering nanogaps form at the interfaces of Al2O3 and the elastomers under stretching (Figure 4b). These result in the dramatic modulation of transmission from a high 90% to a very low 16% at visible wavelengths and does not attenuate after the stretching/releasing of more than 10,000 cycles.2.3. Mechanoresponsive Smart Windows Based on Cracks

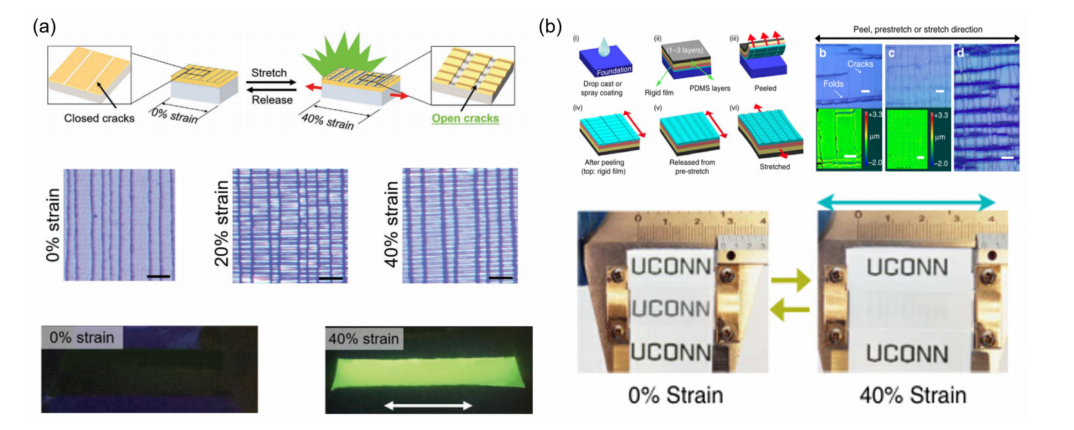

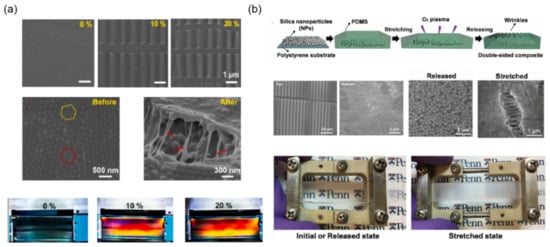

2.5. Mechanoresponsive Smart Windows Based on Tunable Interface Parameters

In addition to optical property modulation by changing the structural parameters such as the number and micro/nano-pattern spacing on the surface, optical pathway opening/closing or the appearance/disappearance of scattered light units by changing the opening/closing state of micro cracks is also an effective means to achieve rapid excitation of fluorescence or rapid decrease of transmittance [33]. Because of the weak binding at the fracture, it usually has highly sensitive properties. Both microscale and nanoscale structural designs have well demonstrated their opportunity in achieving excellent dynamic optical performance. By means of stretching/releasing and revealing/concealing patterns, micro/nanoscale cracks enable tune a series of reversible adaptive optics, e.g., transparency, fluorescent color, and luminescent intensity. Mao et al. reported a simple and highly effective method of mechanochromic materials based on a bilayer structure. This structure is composed of a sputter-coated light-shielding metal layer (Au/Pd) on a PDMS bottom substrate containing the fluorescent dye [34], featuring horizontal and/or vertical micro-scale cracks under stretched material (Figure 3a). The width of cracks opening on the metal light-shielding layer under stretching/releasing endows the UV radiation to stimulate the fluorescent dye, which can exhibit luminescent color embed in the PDMS matrix. The crack opening width can be well tuned via applying different degrees of pre-stretching strain in the preparation process, leading to customizable mechanochromic responses. High sensitivity and excellent durability of the devices are also displayed, which can exhibit great mechanochromic properties after 500 cycles of tensile and release. Zeng et al. introduced a thin rigid composite material film, which was prepared by drop-casting method or spray-coating on the plastic substrate subsequent to the treatment of vinyl-functionalized silane vapor [35]. The surface morphology of the rigid film showed periodical longitudinal cracks which are vertical to the peeling direction and the transverse wrinkles perpendicular to the cracks because of the compressive force originating from the Poisson effect. In the released state, this film shows >88% transmittance at 600 nm and the film becomes highly opaque (transmittance < 29%) under 40% strain (Figure 3b).

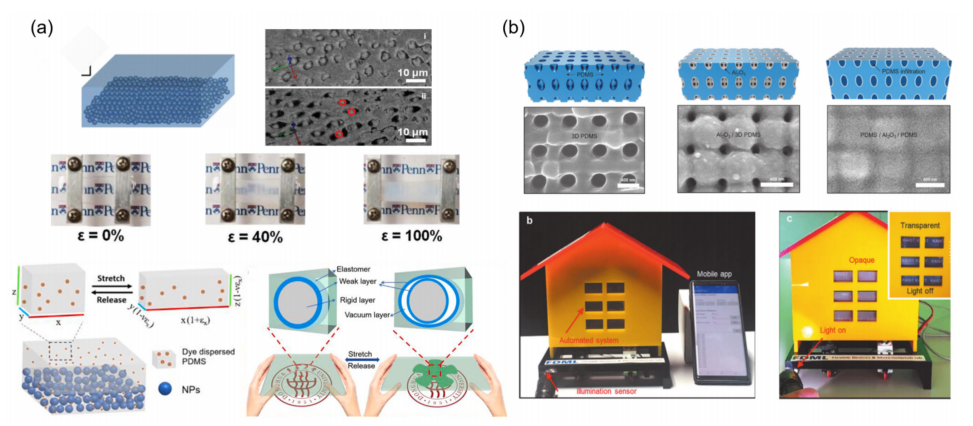

In addition to the generation/disappearance of novel interfaces, the regulation of interfacial structure parameters is also an important factor to change the diffraction and light transmission direction. Typically, there are three types of interface structure parameters: the interface spacing, the interface shape, and the alignment direction.

Figure 3. Construction paths of mechanoresponsive smart windows based on surface crack: (a) surface deposition of metal coating [34] Copyright 2017, John Wiley and Sons, (b) soft substrate/ hard shell [35] Copyright 2017, John Wiley and Sons.

2.4. Novel Interface-Introduced Mechanoresponsive Smart Windows

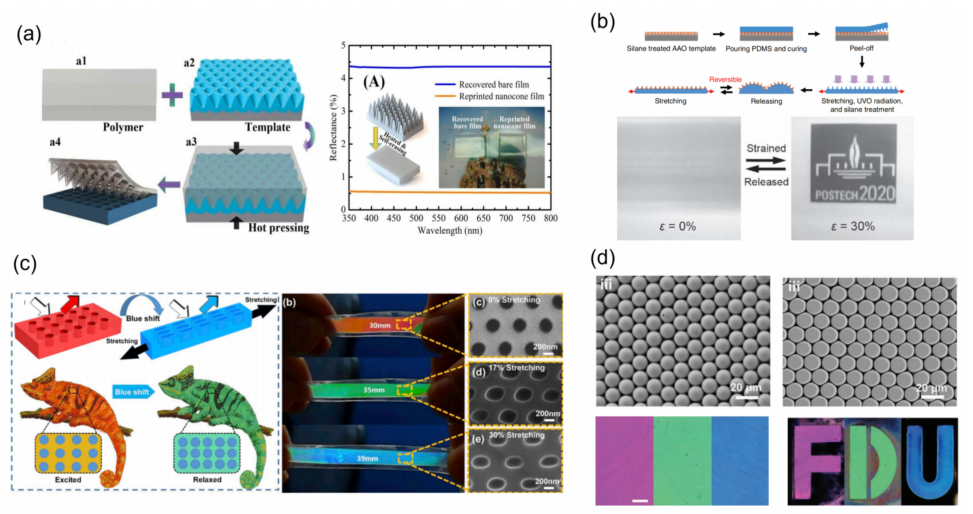

Similar to the surface structure, the interface structure can also dynamically regulate the scattering and interference of light, thus achieving the optical modulation. Moreover, the mechanoresponsive materials based on interface structure regulation can overcome the problem that the surface structure is susceptible to failure by external environment (such as dust, moisture, mechanical load, etc.), and show stronger controllability and stability [36,37]. Based on this, materials that achieve light transmission regulation through dynamic generation/disappearance of novel interfaces have been widely investigated. As shown in Figure 4a, Shu Yang’s group and our group fifirstly proposed the approach to prepare smart window film by combining the nanoparticle arrays with similar refractive indices to elastomers [38]. During the stretching process, a large number of micro/nanooptical interfaces were generated because of the mismatch between the modulus of the soft elastomer and the rigid nanoparticles, which result in a significant decrease in the light transmission of the film. Although the transmittance of this fiilm is up to 70%, it still improves the mechano-optical sensitivity. Therefore, constructing fast-responsive interfaces through the generating/vanishment of scattering under mechanical strain, is an easy and effective way to improve sensitivity. Based on this theory, our group reported an ultrasensitive dynamic optical membrane based on the dye-induced weak boundary layer [39]. This sample exhibits a dramatic decrease in transmittance by 44% at very small strain (15%). Moreover, a total dynamic transmittance rate of ~75% is demonstrated, while this membrane can be reversibly modulated for more than 2000 cycles with stable structural integrity and optical performance.

Figure 4. Methods to novel interface dynamic generation: (a,b) phase separation due to huge elastic modulus difference [38–40] Copyright 2015, John Wiley and Sons, 2021, Elsevier and 2020, John Wiley and Sons.

Cho et al. reported a new type of 3D nanoscale composite film, consisting of an ultrathin Al2O3 nanoshell [40]. Regardless of the stretching direction, a large amount of light-scattering nanogaps form at the interfaces of Al2O3 and the elastomers under stretching (Figure 4b). These result in the dramatic modulation of transmission from a high 90% to a very low 16% at visible wavelengths and does not attenuate after the stretching/releasing of more than 10,000 cycles.

2.5. Mechanoresponsive Smart Windows Based on Tunable Interface Parameters

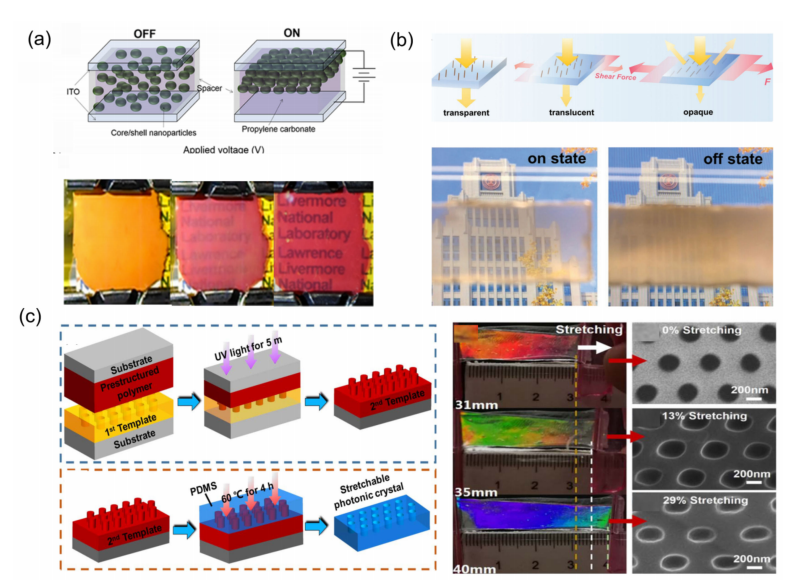

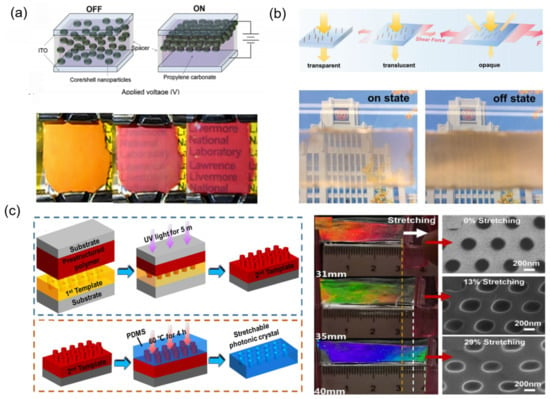

In addition to the generation/disappearance of novel interfaces, the regulation of interfacial structure parameters is also an important factor to change the diffraction and light transmission direction. Typically, there are three types of interface structure parameters: the interface spacing, the interface shape, and the alignment direction. In Figure 5a, Han et al. used colloidal spherical nanoparticles with core-shell structure to successfully synthesize a transparency tunable film in response to electric stimuli [41]. They demonstrated a suspended particles device, which can tune the transparency in the visible wavelength by using colloidal assemblies of nanoparticles. The change in observed transparency can be attributed to the tunable structural ordering of nanoparticle assemblies and the modulation of photonic band structures. Moreover, the macroscopic structure color was able to be changed through regulating the band gap center wavelength along with the lattice constant of nanostructures. As shown in Figure 5b, Li et al. reported a new highly sensitive, shear-responsive smart window, which consists of vertically fixing the Fe

5b, Li et al. reported a new highly sensitive, shear-responsive smart window, which consists of vertically fixing the Fe3

O4

@SiO2

nanochains’ (NCs) array and an elastic matrix of polyacrylamide. At original relaxation state, all Fe3

O4

@SiO2

nanochains stand vertically to the film surface and this flexible film shows optical transparency. When the strain is applied, Fe3

O4

@SiO2

nanochains tilt along the shearing direction, which enables a good shielding effect. Critically, a quite small shear displacement up to 1.5 mm applied on the surface will give rise to tunable optical states, changing from the high transparency state of 65% transmittance to the opaque state of 10% transmittance [42]. In Figure 5c, Zhao et al. designed and fabricated a stretchable photonic crystal via nanoimprinting technology. Periodic cylinder-shaped air holes were embedded in the non-close-packed triangular lattice. This film can switch color over the whole visible light range from red to blue color under a small, applied strain of 29%. In addition, a reversible stretching up to 2000 times also exhibits the stability of shape recovery as well as mechanochromic ability [17].

Figure 5. Mechanoresponsive smart windows with dynamic control of interface parameters: (a) colloidal particle spacing [41] Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society, (b) colloidal par-ticle direction [42] Copyright 2021, John Wiley and Sons, (c) spacing and shape of hole [17] Copyright 2019, Iop Publishing (Bristol, UK).

2.6. Mechanoresponsive Smart Windows Based on Surface–Interface Synergy Effect

In order to enhance the optical modulation range and achieve a multi-state, the synergistic surface–interface modulation is an effective approach. It is possible to achieve color and transmittance modulation based on multiple effects at the same time. Therefore, surface–interface synergy effect has unique advantages in multi-state display and precise regulation.As shown in Figure 6a, a large-area mechanochromic film is reported by Qi et al. based on a novel design of bilayer PDMS film including angle-independent and angledependent structural colors through bottom-up bar coating [43]. The angle-independent structural color is attributed to the long-range disordered but short-range ordered structure of polystyrene (PS) nanoarrays. Meanwhile, angle-dependent structural color is generated due to the stretching of surface wrinkling. Moreover, the cracks and surface wrinkles of PS nanoarrays resulting from the tensile enhance the scattering effect of bilayer film and reduce the transmittance of the light. Furthermore, pressure-induced surface morphology rearrangements can remove the wrinkling behavior. Therefore, the properties of programmable mechanochromic responses can be achieved. The pressure-encoded invisible complex information can be reversibly displayed by stretching.

As shown in Figure 6a, a large-area mechanochromic film is reported by Qi et al. based on a novel design of bilayer PDMS film including angle-independent and angle-dependent structural colors through bottom-up bar coating [43]. The angle-independent structural color is attributed to the long-range disordered but short-range ordered structure of polystyrene (PS) nanoarrays. Meanwhile, angle-dependent structural color is generated due to the stretching of surface wrinkling. Moreover, the cracks and surface wrinkles of PS nanoarrays resulting from the tensile enhance the scattering effect of bilayer film and reduce the transmittance of the light. Furthermore, pressure-induced surface morphology rearrangements can remove the wrinkling behavior. Therefore, the properties of programmable mechanochromic responses can be achieved. The pressure-encoded invisible complex information can be reversibly displayed by stretching.

Figure 6.

Two strategies of mechanoresponsive smart windows based on surface and interface modulation synergistically: (a) surface wrinkle, novel interface dynamic formation dynamic control of interface parameters [43] Copyright 2021, Elsevier, (b) surface wrinkle and novel interface dynamic generation [44] Copyright 2018, John Wiley and Sons.

In order to realize the highest transmittance modulation under the special application requirements, Kim et al. presented a novel strategy to prepare an on-demand smart window by integrating the synergetic optical effects due to the tunable wrinkled geometry and nanovoids generated by the surrounding silica particles embedded in PDMS film (Figure 6b) [44]. By carefully varying the wrinkle shape, the size of silica particle and stretching strain, a great optical transmittance modulation in the visible band to near infrared range is realized, while with a relatively small strain up to 10%. At 0% strain, the film shows 60.5% transmittance at the wavelength of 550 nm due to the light diffraction caused by the initial wrinkles. Upon stretching to the pre-strain level (10%), a maximum transmittance (86.4%) is obtained at a visible wavelength of 550 nm. While at 40% strain level, the film demonstrates a significantly low transmittance (25.2%).

6b) [44]. By carefully varying the wrinkle shape, the size of silica particle and stretching strain, a great optical transmittance modulation in the visible band to near infrared range is realized, while with a relatively small strain up to 10%. At 0% strain, the film shows 60.5% transmittance at the wavelength of 550 nm due to the light diffraction caused by the initial wrinkles. Upon stretching to the pre-strain level (10%), a maximum transmittance (86.4%) is obtained at a visible wavelength of 550 nm. While at 40% strain level, the film demonstrates a significantly low transmittance (25.2%).