Post-harvest diseases can be a huge problem for the tropical fruit sector. These fruits are generally consumed in natura; thus, their integrity and appearance directly affect commercialization and consumer desire. Anthracnose is caused by fungi of the genus Colletotrichum and affects tropical fruits, resulting in lesions that impair their appearance and consumption. Antifungals generally used to treat anthracnose can be harmful to human health, as well as to the environment. Therefore, essential oils (EO) have been investigated as natural biofungicides, successfully controlling anthracnose symptoms. The hydrophobicity, high volatility, and oxidative instability of essential oils limit their direct application; hence, these oils must be stabilized before food application. Distinct delivery systems have already been proposed to protect/stabilize EOs, and nanotechnology has recently reshaped the food application limits of EOs. This review presents robust data regarding nanotechnology application and EO antifungal properties, providing new perspectives to further improve the results already achieved in the treatment of anthracnose. Additionally, it evaluates the current scenario involving the application of EO directly or incorporated in films and coatings for anthracnose treatment in tropical fruits, which is of great importance, especially for those fruits intended for exportation that may have a prolonged shelf life.

1. Introduçãction

A

ant

hracnose

é uma doença pós-colheita grave que afeta várias frutais a serious post-harvest disease that affects various tropica

is el and subtropica

is, comol fruits such as banana, mang

a, mamão e abacateo, papaya, and avocado [

1 ].

AThe infec

ção é causada por fungos do gênerotion is caused by fungi of the genus Colletotrichum ,

principalmente na fase de floração dos frutos, permanecendomainly in the flowering stage of the fruits, remaining latent

e até o desenvolvimento após a colheita e estendendo-se durante o armazenamento. A infecção pode causar aspecto until development after harvest and extending during storage. Infection can cause an undesirable visual

indesejável, aappearance, accelera

r o amadurecimento dos frutos e, em estágios mais avançados, levar ao apodrecimento dos frutos. Esses sintomas prejudicam a cote fruit ripening, and, in more advanced stages, lead to fruit rot. These symptoms impair the commercializa

ção etion and exporta

ção das frutas, inibindo a venda e otion of fruits, restraining selling and consum

option [

2 ,

3 ].

AlémIn dos impactos econômicos e frutíferos, o gêneroaddition to the economic and fruit impacts, the Colletotrichum podge

representar um risco para a saúde humana, pois as espénus may pose a risk to human health, because the species

C. atramentum ,

C. graminicola ,

C. dematium, eand C. gloeosporioides forha

m relatadas como causadoras de cve been reported to cause keratomi

osecosis.

C. truncatum foiwas errone

amenteously associa

do a cinco casos deted with five cases of ophthalmic infec

ções oftálmications origina

lmente causadas porlly caused by C. dematium [

4 ].

Esse estudo revelou, na época, aThis study revealed, at the time, the import

ância do uso de métodosance of using molecular

es para methods to identif

icar as espéy species. Recent

emente, a espéciely, the species C. chlorophyti was fo

i consideradaund to be respons

ável por cible for mycotic keratit

e micótica em um homem de 82 anosis in an 82-year-old man [

5 ].

FSynthetic fungicid

as sintéticos como tes such as thiabendazol

ee and imazalil

são os principais tratamentos utilizados no manejo de frutas paraare the main treatments used in the management of fruits to minimiz

ar os efeitos dae the effects of infec

çãotion [

1 ,

3].

NHo

entanto, vários fitopatógenos sãowever, several phytopathogens are resist

entes ao tant to thiabendazol

. Os fe. Fungicid

as podem ser prejudiciais à saúde humana, pois o acúmulo nos tecidos pode gerares can be harmful to human health, as accumulation in tissues can generate hepatotoxici

dade, toxicidade da glândula adrenalty, adrenal gland toxicity, carcinogenici

dadety/mutagenici

dade, nefty, nephrotoxici

dade e distúrbios metabólicos. Além disso, podem causar danos ao meio ambiente e afetar aty, and metabolic disorder. In addition, they can cause damage to the environment and affect biodiversi

dade. Do ponto de vista do mercado de alimentos, os ty. From the food market point of view, consum

idores estão se tornando avessos àers are becoming averse to the presen

ça de aditivos sintéticos. Assim, faz-sece of synthetic additives. Thus, it is necess

ária a busca por tratamentos eficazes, seguros eary to search for effective, safe, and natura

is que não afetem a saúde do consumidor ou o meio ambiente e, quando possível, não promovam alteração nas propriedades sensoriais dos alimentol treatments that do not impact consumers’ health or the environment and, when possible, promote no change in the sensory properties of foods [

6 ,

7 ].

NeIn this

se cenário, scenario, natural fungicid

as naturais estão sendo aplicados como ferramenta de controlees are being applied as a tool for microbiol

ógico e, portanto, de doenças pós-colheita. O uso de óleosogical control and, therefore, for post-harvest diseases. The use of essen

ciais paratial oils to preven

ir a propagação dat the spread of infec

ção tem sido estudado como uma opção de tion has been studied as a natural fungicid

a naturale option. Andrade

eand Vieira [

8 ],

por exemplo, estudaram o efeito do anisfor example, studied the effect of anise (

Pimpinella anisum ), tea tree (

Melaleuca alternifolia ),

capim-limãolemongrass (

Cymbopogon citratus ),

hortelãmint (

Mentha piperita ),

alecrimrosemary (

Rosmarinus officinalis )

e canela, and cinnamon (

Cinnamomum zeylanicum)

por messe

io de testesntial oils through in vivo (

aplicação direta) e direct application) and in vitr

o para avaliar ao tests to assess conidia germina

ção dos conídios. Os autores notaram um efeito fungitóxico etion. The authors noticed a fungitoxic and fungist

ático da maioria dos óleos usados em diatic effect of most oils used in different

es concentra

ções. Outro estudotions. Another study demons

trou por meio de testes in vitro o potenctrated through in vitro tests the potential us

o do óleoe of cinnamon essen

cial de canelatial oil (

Cinnamomum zeylanicum o

ur Cinnamomum verum )

no crescimento mion mycelial

e na geminação de esporosgrowth and spore twinning of de C. acutatum isola

ted

o de from kiwi.

Neste estudo, o óleo de canela mostrou efeitosIn this study, cinnamon oil showed fungist

áticos eatic and fungicida

s eml effects at concentra

ções de 0,tions of 0.175 µL/mL

e 0,and 0.2 µL/mL, respectiv

amenteely [

9 ].

AThe direct ap

licação direta de OEs na superfície do fruto torna-se um desafio, devido àplication of EOs to the fruit surface becomes a challenge, due to the volatili

dade dos OEty of EOs [

10 ].

Assim, é comum a aplicação de óleos essenciais emHence, it is common to apply essential oils in formula

ções de revestimentos poliméricos para frutas, visando aumentar sua vida útil. No entanto, a alta hidrofobicidade dessastions of polymeric coatings for fruits, aiming to increase their shelf life. However, the high hydrophobicity of these subst

âncias dificulta a obtenção de umaances makes it difficult to achieve a homogeneous dispers

ão e espalhabilidade homogênea em toda a superfície da fruta quando ela é simplesmente adicionada à ion and spreadability over the whole fruit surface when it is simply added to the coating formula

çãotion.

A do revestimento.

Ulivery system

desi

stema de entrega projetado para proteger e entregar os compostos desejados na hora e no lugar certo é umagned to protect and deliver the desired compounds at the right time and place is a viable alternati

va viável para superar os desafios do uso de óleos essenciais em frutas. Nesse sentido, a aplicação de OEs na forma deve to overcome the challenges of using essential oils in fruits. In this sense, the application of EOs in the form of emuls

ões é uma estratégia para melhorar sua ions is a strategy to improve their dispersibili

dade e ty and homogenei

dadety. Emuls

ões são sistemas nos quais dois líquidos imiscíveis são ions are systems in which two immiscible liquids are homogen

eizados para formar uma mistura de gotículas esféricas (fase ized to form a mixture of spherical droplets (dispers

a) em um líquido circundante (fase contínua). Os óleosed phase) in a surrounding liquid (continuous phase). The essen

ciais são geralmentetial oils are usually incorpora

dos em revestimentos na forma de emulsões de óleo em água (o/a)ted into coatings in the form of oil-in-water (o/w) emulsions. Depend

endo daing on the concentra

ção, as emulsões tion, conven

cionais de OE podem gerar alterações na cor e no sabor da fruta, além de levar àtional EO emulsions can generate changes in fruit color and flavor, in addition to leading to EO degrada

ção do OE quandotion when expos

tas a condições ambientais extremaed to extreme environmental conditions (temperatur

ae, pH, ox

igênio, luz e umidadygen, light, and moisture) [

11].

OuAnot

ra desvantagem é a rápida liberação de compostos voláteis, o que pode prejudicar sua ação biológica na conservação dos frutosher drawback is the fast release of volatile compounds, which can impair their biological action on fruit preservation [

12 ].

AoWhen lidar com óleos essenciais para revestimento oudealing with essential oils for coating or film formula

ção de filme, as tion, nanoemuls

ões têm recebido atençãoions have received substan

cial nos últimos anos devido às suas propriedades físico-químicas e funcionais. As ntial attention in recent years due to their functional and physicochemical properties. Nanoemuls

ões sãoions are emuls

ões com raio de gota variando entre 10 eions with a droplet radius ranging between 10 and 100 nm,

que são mais which are more resist

entes àant to coalesc

ência e à ence and phase separa

ção de fases quandotion when compar

adas às emulsões ed to conven

cionais. O tamanho da gota está diretamente relacionado à cor dastional emulsions. The droplet size is directly related to the color of nanoemuls

ões, que pode variar de ions, which can vary from transparent

e a levemente turva to slightly cloudy [

13 ,

14 ].

NEssential oil nanoemul

sões de óleos essenciais aplicadas em sistemas para prolongar a vida de prateleira de alimentos podem melhorar a funciosions applied in systems to extend food shelf life might improve the functionality of EOs by increasing the oil droplet surface area and, consequently, the contact area between the active agents and the food, enabling the use of smaller doses of essential oils [13,15]. In

a

lidade dos OEs por aumentar a área de superfície das gotículas de óleo e, consequentemente, a área de contato entrddition, oil droplets on the nanoscale are capable of easily diffusing into the microorganisms’ cellular membrane and disrupting its organization, promoting cellular internal content leakage and cellular death, which considerably improves antimicrobial capacity.

The

use o

s princípios ativos e o alimento, possibilitando o uso de doses menores de óleos essenciais.13f essential oil nanoemulsions in active films and coatings is a promising alternative to increase the shelf life of anthracnose-susceptible tropical fruits. The performance of different essential oil emulsions in reducing deterioration levels depends on the chemical composition and the emulsion properties. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to focus ,on 15current ].trends Além disso, gotículas de óleo em nanoescala são capazes de se difurelated to the production of emulsions, especially nanoemulsions, involved in the development of active films and coatings for the preservation of tropical and subtropical fruits against the effects of infection by the genus Colletotrichum. In

d thi

r facilmente na membrana celular do microrganismo e desorganizar sua organização, promovendo vazamento do conteúdo interno celular e morte celular, o que melhora consideravelmente a capacidade antimicrobianas context, three main topics are investigated: (a) the characteristics of the fungus and the disease that can lead to tropical fruit degradation during storage and, consequently, to significant economic losses; (b) the characteristics of essential oils and their mechanism of action that makes them potential natural food additives for fruits; (c) the use of conventional and nanoemulsions in edible films/coatings for inhibition of fungal growth and consequent prevention of anthracnose symptoms.

2. Anthracnose em Frutos in Tropicail Fruits

2.1. Dados Econômicos

Fomic Data

Tr

utas tropica

is el and subtropica

is são amplamentel fruits are widely consum

idas em todo o mundo; portanto, aed worldwide; therefore, the quali

dade e ty and diversi

dade dessas frutas devem serty of these fruits must be preserv

adas. Os três principais países produtores de frutas tropicais são ed. The three main tropical fruit-producing countries are China,

Índia e Brasil. O Brasil, apesar de serIndia, and Brazil. Brazil, despite being respons

ável pela terceira maiorible for the third largest fruit produ

ção de frutas do mundo, tem uma pequenaction in the world, has a small representati

vidade nos patamares mundiais de exportação de frutas. Apenas cerca de três por cento de suaon in world fruit export levels. Only approximately three percent of its fruit produ

ção de frutas foi ction was export

ada emed in 2021.

O não fortalecimento de acordos The failure to strengthen interna

cionais que possuem padrões rígidos de cotional agreements that have strict standards of commercializa

ção é o principal fator que tion is the main factor contribu

i para os baixos níveis deting to the low exporta

ção. A fruticultura cotion levels. Commercial

exige cada vez maifruit growing increasingly requires prof

iessionalism

o e regulamentação específica, e a and specific regulation, and fungal contamina

ção fúngica pode afetar diretamente esse sistema cotion can directly affect this commercial

. O baixo volume exportado está relacionado, entre outras causas, à perda de qualidade durante o armazenamento e system. The low exported volume is related, among other causes, to the quality loss during storage and transport

e, o que pode , which may result

ar na não aceitação das frutas pelos países in the nonacceptance of fruits by the import

adores. Muitas dessas frutasing countries. Many of these tropica

is el and subtropica

is sãol fruits are susce

tíveis àptible to contamina

ção por espécies detion by species of Colletotrichum [

16 ,

17 ].

A

Fruit loss

pe

rdas de frutas estão relacionadas à diminuição da quantidade de alimentos disponíveis paras are related to the decrease in the amount of food available for human consum

o humano nas fases de produção, pós-colheita, armazenamento eption in the production, post-harvest, storage, and transport

e. Segundo a phases. According to the FAO [

18 ], 14%

dos alimentos do mundo são perdidos após a colheita e antes de chegarem ao varejoof the world’s food is lost after harvesting and before reaching retail. Udayanga et al. [

19] re

lported that

aram que grand a large part

e das frutas cultivadas em países da região asiática se perde devido ao manuseio inadequado, transporte ine of the fruits grown in countries in the Asian region are lost due to improper handling, inefficient

e e contaminação por fungos e bactérias. A comercialização e exportação dessas fruta transport, and fungal and bacterial contamination. The trade and export of these fruits depend

em do cumprimento de rígidos padrões fitossanitário on the compliance with strict phytosanitary standards impos

tos pelos países desenvolvidos, o queed by developed countries, which has an impact

a no comércio agrícola dos países em desenvolvimento (grandes on agricultural trade in developing countries (major produ

tores de frutascers of tropica

is). A antl fruits). Anthracnose

é uma doença capaz de causar impactos econômicos; portanto,is a disease capable of causing economic impacts; therefore, technological invest

imentos tecnológicos sãoments are important

es para to preven

ir os danos causados por essa doençat the damage caused by this disease.

2.2. O procThesso infeccioso de frutas t Infectious Process of Tropicais porl Fruits by Colletotrichum

O proc

The

sso de contamina

ção de frutas sadias étion process of healthy fruits is favore

cido pelos fatores ambientais das regiõesd by the environmental factors of tropica

is. As causas sãol regions. The causes are divers

as e variam de acordo com a região e o tipo de produção. Geralmente, altase and vary according to the region and the type of production. Generally, high temperatur

as (cerca dees (around 27 °C)

e umidade (cerca deand moisture (around 80%)

afetam fortemente o desenvolvimento da anthighly affect anthracnose

em frutasdevelopment in tropica

is. Períodos prolongados de chuva em regiõesl fruits. Prolonged periods of rain in tropica

is juntamente com altasl regions together with high temperatur

aes favor

ecem a the progress

ão da doença. A umidade cion of the disease. Constant

e na superfície da folha e moisture on the leaf surface stimula

o processotes the infec

cioso e o crescimento de fungos. No caso das frutas, a maioria se perde devido àtious process and fungal growth. In the case of fruits, most are lost due to contamina

ção durante o processo de produção e amadurecimentotion during the production and ripening process [

17].

OThe control

e dos fatores ambientais é um ponto importante a ser of environmental factors is an important point to be consider

ado no processo de pós-colheita e armazenamento. As doenças pós-colheita são uma das principais causas de perdas de frutas e hortaliças no mundo. Nesse sentido, a anted in the post-harvest and storage process. Post-harvest diseases are a major cause of fruit and vegetable losses in the world. In this sense, anthracnose

torna-se uma grande preocupação para osbecomes a major concern for produ

tores, pois o fungocers because the fungus associa

do a essa doença tem causado perdas em muitas espécies de manga, mamão, abacateted with this disease has caused losses in many species of mango, papaya, avocado, banana, ca

jushew, carambola, g

oiaba, maracujá e outras frutauava, passion fruit, and other fruits [

17 ,

20 ]

.

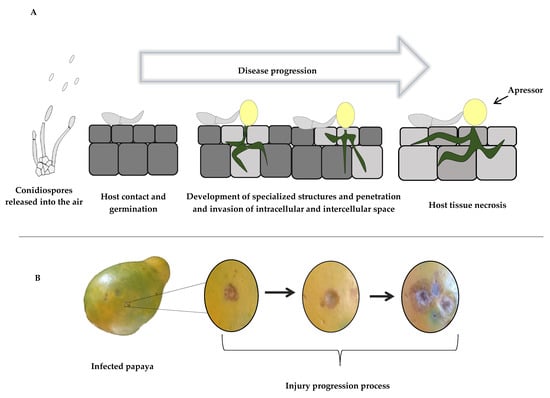

A

ant

hracnose

é uma doença cis a disease characteriz

ada pelo aparecimento de sintomas principalmente durante o amadurecimento dos frutos, ou seja, no período pós-colheita, em espéciesed by the appearance of symptoms mainly during fruit ripening, i.e., during the post-harvest period, in clima

téricas. Folhas mortas e galhos ou frutos infectados podem ser uma fonte decteric species. Dead leaves and infected branches or fruits can be a source of contamina

ção, e ation, and infec

ção pode ocorrer em qualquer estágio entre a frutificação e a colheita. Os conidiósporos, estruturas germinativas de fungos, podem sertion can occur at any stage between fruiting and harvesting. Conidiospores, fungal germ structures, can be dispers

os pelo vento ou pela água. Quandoed by wind or water. When dispers

os, podem aderir à superfície dos frutos eed, they can adhere to the surface of the fruits and germina

r em pouco tempo. Logo depois,te in a short time. Soon after, they produ

zem o tuboce the germina

tivo, quel tube, which penetra

na cutícula do fruto. Após a tes the cuticle of the fruit. After penetra

ção, as hifas podemtion, the hyphae can coloniz

ar a parede do fruto. As lesões epidérmicas iniciais são pequenas ee the fruit wall. The initial epidermal lesions are small and circular

es, de coloração marrom-escura ou, em alguns casos, negras. Pequenas lesões, with a dark brown or, in some cases, black color. Small circular

es ficam encharcadas de água, parecendo mais profundas do que a superfície do fruto. Podem aumentar de tamanho com a idade, e o centro de uma mancha mais velha torna-se enegrecido e desenvolve massas lesions become soaked with water, looking deeper than the surface of the fruit. They may increase in size with age, and the center of an older spot becomes blackened and develops gelatino

sas de esporos rosa ou laranja. Em poucos dias, com o aumento de tamanho durante o amadurecimento, as lesões aus masses of pink or orange spores. In a few days, with the increase in size during ripening, the lesions present

am pontos iniciais de initial points of necros

e, levando à perda dos frutos.is, leading to fruit loss (Figurae 1 ) [

19 ,

21 ].

Figurae 1. EsquSchema da visãoe of microscópicaopic ( A ) eand macroscópicaopic ( B ) do desenvolvimento da doença antview of anthracnose disease development.

2.3. O Thestilo de vida do Colletotrichum e sua relação com os sintomas da antLifestyle and Its Relationship with the Symptoms of Anthracnose

A

The rela

çãtio

entre fungos enship between fungi and plant

as é altamentes is highly complex

a, pois, as it depend

e de mudanças on changes rela

cionadas às dited to different

es fases da vida da planta, bem como do desenvolvimento fisiológico stages of plant life, as well as on the physiological development, resist

ência do hospedeiro, do ambiente e dosance to the host, the environment, and genes associa

dos à doençated with the disease [

22 ].

O gêneroThe Colletotrichum égenus is form

ado por um grupo deed by a group of important

es fitopatógenos que causam grandes perdas de frutas, hortaliça phytopathogens that cause large losses of fruits, vegetables, cerea

ils, gra

míneas e plantas osses, and ornamental plants in tropical regions [19]. Ther

e is n

amentais em reo established standard for the lifestyle of the different species and groups that make up the Colletotrichum g

enus, hamperi

ões tropicais [ng the control of the diseases caused by 19them [23].

The Nãlifestyle o

existe um padrão estabelecf this genus can be broadly categorized by some characteristics that arise throughout the life cycle of the fungus. The Colletotrichum genus can be classifi

ed

o para o estilo de vida das diferentes espécies e grupos que compõem o gênero as follows: (i) necrophytes, almost all of which use lytic enzymes or toxins to cause cell death at some stage of the infectious process; (ii) endophytes, which inhabit plant cells in the process of symbiosis without causing apparent disease; (iii) quiescent species, whose fungus remains in latency or a dormant stage with no activity and generally becomes active in the post-harvest moment; (iv) biotrophic species, a characteristic common in the early lifestyle of the genus Colletotrichum, , dificultando o cwhen the fungus remains alive inside the cells, actively absorbing the plant’s metabolites for its development without killing the cells [24,25].

The co

nmplex lifest

rolyle of the Colletotrichum ge

nus das doenças por eles causadas [associated with its ability to change style and the potential to infect different host species are factors that hinder the management of contaminated fruits and vegetables. The lifestyle 23of ].

Othis ge

stilo de vida desse gênero nus is highly regulated by specific genes and by specific biochemical interactions, in which enzyme activity and the production of secondary metabolites specific to the pathogen–host interaction occur [25]. In this p

ro

de ser amplamente categorizado por algumas caraccess, it is necessary to consider not only symptomatic fruits but also asymptomatic ones, as both can disperse the infectious agent to other plants. Knowledge of the lifestyle, the different stages of development, and the mechanisms that species of Colletotrichum use for t

he disease

rísticas que progression is essential to avoid commercial losses and allow for the exportation of fruits and vegetables.

The s

tru

rgem ao longo do ciclo de vida do fungocture of the host plant is an important point in the pre-infection moment, since the presence of cuticles, stomata, and trichomes and the thickness of the epidermis can be initial barriers to the infection process [26,27].

O gêGener

oally, Colletotrichum infections start with the germination of conidia and the formation of sp

ode ser claecialized infectious structures (appressoria) that facilitate the entry through the cuticle and cell wall [28]. However, the s

pecies

C. gloeosporioides, when i

nf

icado da seguinte forma:ecting blackberry leaves, for example, formed specialized vesicles on or inside stomata, allowing the hyphae to enter the leaves [29]. (i)In necanother case, C. orbiculare pr

ófoduced an appressorium to di

tas, quase todas utilizando enzimas lísrupt the plant’s surface and cause lytic enzymes to digest the cuticle and cell wall, allowing the conidia of this species to adhere [30].

After penetrati

on, different spec

as ou toxinas para causar a morte celular em alguma fies can start an intracellular or subcuticular hemibiotrophic process, generating an asymptomatic biotrophic phase without cell death. Subsequently, fungi can enter the necrotic phase, where secondary hyphae grow in the intracellular and intercellular space, which secrete degrading enzymes from the wall, leading to cell death [23]. In a

ddition to this

e do p mechanism, some species may initiate the process

o infeccioso; (ii) endófitos of subcutaneous intramural necrotrophic infection, where fungi grow under the cuticle between the periclinal and anticline walls without the penetration of protoplasts [28,

31]. qInfections cau

e sed by C. gloeosporioides ha

ve already b

itam células vegeen reported as intracellular hemibiotrophic in guava fruits, where vesicles and hyphae of infection were formed in the initially infected epidermal cell [32].

The

int

ais em processo de simbiose sem causar doença aparenteraction between the host and the microbiological agent during the development of anthracnose is complex and dynamic. The different lifestyles that this genus can adopt make the effective and economical treatment of this disease in tropical and subtropical fruits even more difficult [25]. Losse

;s from (iii) espécies quiescecontamination can impact the entire production process, leading to economic damage [33]. The cont

rol and manageme

s, cujo nt risks associated with the infection by Colletotrichum are fu

ndamen

go permanetal points to avoid the dispersion of the fungus and contamination of other fruits.

3. Conventional Treatments for Anthracnose Prevention

Tropic

al and subtropical fruits have

em estado de latência ou dormência sem atividade e been produced for subsistence and local distribution for many years. Investments in technology and improvements in transport and storage conditions have made the global commercialization of these fruits possible. The Southern Hemisphere has undergone significant changes in its production processes to reach the ideal standard for fruit exports to the Northern Hemisphere [34]. However, some challenge

s such as the lack of technology and infra

lmente se torna ativo no momento pós-colheita; (structure, high insect infestations, undesirable microbial growth, the appearance of lesions and stains due to improper handling or transport, and the prevalence of high temperatures and humidity still make the commercialization process difficult. In this context, the prevention of post-harvest diseases is essential to maintain the fruit trade and to reduce losses.

3.1. Physical Treatments

Duri

ng the post-harv

) espécies biotróficas,est stage, some traditional physical and chemical treatments can be applied to control the symptoms of anthracnose. Alvindia and Acda [35] ceva

racterística comum no estilo de vida inicial do gêneroluated the effects of hot water application on anthracnose-causing mango crops. In this study, treatment at 53 °C for 20 min had a significant effect on reducing the germination of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides spores after 48 h,

preserving the fruit qua

ndo o fungo permlity. However, the high amount of water used is a disadvantage of this type of treatment.

Other physica

l treatmen

ece vivo dets have been evaluated in recent studies. Fischer et al. [36] used UV-C radiation

t

ro das células,o control anthracnose symptoms of and stem rot in avocado fruits inoculated with C. gloeosporioides. The a

bpplied doses

orv of UV-C radiation (0.34–0.72 kJ·m−2) were

n

do ativamente os metabólitoot effective in reducing the occurrence of the disease. Contrarily, by applying a higher dose of radiation (3.0 and 4.0 kJ·m−2), Wanas

inghe da and Damunupola [37] successfully supp

lressed ant

a para seu desenvolvimento sem matar as células [hracnose symptoms on tomatoes. Nonetheless, these results should be evaluated with caution, because the authors observed the presence of antifungal compounds in tomato skins. Furthermore, radiation is still seen as a problem for consumers. Although it has minimal ambient impact, the lack of information about possible changes in food and, consequently, the possible impacts of this type of treatment on human health remain the main barriers to 24this ,method’s 25acceptance [38].

O

3.2. Chemical Treatments

Some chemical tre

stilo de vida complatments are applied to reduce the symptoms of anthracnose in fruits, but most are toxic or less efficient over time as the pathogen’s resistance increases. Vieira et al. [39] e

xvaluated the efficacy of thio

do gênerophanate-methyl, a fungicide frequently used to control Black Sigatoka, on the growth of Colletotrichum musae, which ca

ssociado à sua capacuses anthracnose in bananas. Their results suggested a potential resistance of Colletotrichum musae to thi

ophanate-methyl, lead

ade de muding to treatment inefficacy. Thiabendazole showed poor growth control of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in pa

paya, wher

de estilo e ao potencial de infectaeas the fungicides imazalil, prochloraz, propiconazole, and tebuconazole showed a positive effect by interrupting the germination of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides spor

es dwhen applied at 50 ppm [40]. Even wi

th satisf

erentes espécies hospedeiras são fatores que diactory results, the repeated and continued use of these pesticides can change the balance of ecosystems, increase the incidence and severity of diseases, and still select isolates resistant to these chemical compounds [41].

A successficultam o manejo de frutas e hortaliças contaminadas. O estilo de vida desse gênero é altamente re treatment for anthracnose control must consider environmental health impacts. Resources must be selected to maintain their balance in the environment, avoiding waste, without causing pollution or future damage. The treatments available to control anthracnose symptoms still face barriers, which can make them unfeasible or ineffective. The use of chemical or physical agents to reduce the growth of the Colletotrichum genulado por genes específicos e por interações bioquís must meet safety criteria and environmental preservation. Therefore, an increasing number of studies have investigated potential natural pesticides capable of assuring fruit integrity, as well as safety and a reduction in losses.

4. Essential Oils

4.1. General Characteristics and Potential Applications

Several chemical s específicas, nas quais ocorre a atividade enzimática e a produção de ubstances have been applied to reduce the effects caused by fruit contamination after harvesting. Lately, most food producers have been forced to change this approach to meet the growing demand for chemical-free products, as the use of sustainable and safe natural products is progressively being demanded. Therefore, to meet consumer criteria, industries have had to look for new sources of compounds with effective action in the preservation process.

EOs are secondary plant metab

óoli

tos secundários específicos para a interação patógentes that consist of a complex mixture of compounds extracted from various parts of plants, such as leaves, flowers, buds, seeds, branches, bark, herbs, wood, fruits, and roots, and they have been increasingly explored due to their insecticide, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiallergic, and anticancer potential [42,43]. The bio

-activity of th

ospedeiro [e molecules present in EOs makes them very attractive to the food industry, 25both ].for Nesse processo, é necessário considerar não apenas os fdirect application, as a potential natural preservative in food formulation, and for indirect application, in the production of active packaging, e.g., to improve food preservation by preventing pathogenic and/or spoilage microorganisms [44,45].

Car

uot

os sintomáticos, mas também os assintomátienoids, alkaloids, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, isoflavonoids, and aldehydes are the groups commonly found in the composition of EOs [43]. Moreover, EOs are ric

oh in substances classified as terpenes,

pois ambterpenoids, and phenylpropanoid homologs [46], which co

ntain s

podem dispersar o agente infeccioso para outras plantas. O conhecimenteveral compounds associated with different bioactivities. Some studies have suggested that the antimicrobial activity of essential oils may be directly related to major components, but there is also a possibility of synergy or antagonism among the different components [47]. Fo

r doexample, Hyldgaard, Mygind, and Meyer [48] des

tilo de vidacribed the low efficiency of isolated terpenes against the growth of Escherichia coli,

Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, and

a the fungus

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and

specif

erentes fases de ic terpenoids such as carvacrol and thymol have been reported as potent antimicrobial agents when isolated. Chavan and Tupe [49] de

mons

envolvimento e dos mtrated the synergism between carvacrol and thymol in vitro and in vivo, which promoted membrane damage and cytoplasmic leakage of wine spoilage yeasts.

The canismos que as espécies dharacteristics of different essential oils can be exploited to prevent or reduce the damage Colletotrichumcausoed by para a progressão da doençanthracnose in fruits. However, for the treatment to be effective, it is necessary to elucidate the mechanisms of action of the different components of EOs against fungal growth.

4.2. Mechanism of Action against Fungi

The mechanism of a

ction éof essen

cial para evitar perdas comerciais e permitir a exportação de tial oils against fungal development is not yet fully understood. Nevertheless, some studies have suggested potential antimicrobial activity based on the functional group structures of compounds present in EOs [50]. The structure of

r compou

tas e hortaliças.

Ands in EOs determines their hydrophobicity, allowing passage est

rutura da planta hospedhrough the cell wall and membrane, leading to increased permeability and, consequently, to cell death or inhibition of sporulation and germination of fungi [51]. The

li

ra é um ponto importante no mometerature reports that phenolic compound structures are associated with the high antimicrobial potential of clove, thyme, oregano, cinnamon, rosemary, sage, and vanilla EOs [47].

Hydrophobic compon

ent

o da pré-infecção, pois a prs can interfere with synthesis reactions in wall structures, affecting morphogenesis and hyphal growth [52]. Some

s

ença de cutículas, estômatos e tricomas e a espesstudies have suggested that hydrophobic compounds interact with ergosterol, the essential molecule that maintains the cellular integrity, viability, function, and normal growth of the fungus. Clove and thyme essential oils are effective in inhibiting ergosterol synthesis [53,54]. Changing the flu

idity and per

a da epiderme podem ser barreiras inicmeability of the membrane leads to loss of ions, collapse of the proton pump, and reduction in membrane potential; moreover, in some cases, interactions between phenolic compounds and membrane proteins can occur, precipitating them and resulting in leakage of intracellular components [55,56].

The anti

funga

is ao processo de infecçãol activity of essential oils may also be related to the disruption of fungal mitochondria. Some EOs can inhibit specific enzymes, such as mitochondrial ATPase, malate dehydrogenase, and succinate dehydrogenase, decreasing energy metabolism [

57]. 26In addition,

essential 27oils can ].alter Geralmente, as infecções porthe mitochondrial membrane of fungi, changing electron fluxes through the electron transport Colletotrichumchain and, thus, produc

omeçam com a germinação ding altered levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can oxidize and damage important molecules such as DNA, proteins, and lipids [58]. The

inc

onídios e a formação de estruturas infeccirease in ROS is closely related to the biochemical process of cell death. Terpenes, for example, are structures capable of causing an increase in ROS species [54].

So

me s

as especializadas (atudies have shown promising results using essential oils to inhibit fungal growth. Essential oils of oregano, onion, mint, basil, and rosemary were tested against Fusarium sp

., Aspergillus ochraceus, Aspergillus flavus, and Aspergillus niger. Ore

gano ess

órios) que facilitam a entrada pela cutícula e parede ceential oil showed a fungicidal and fungistatic effect on all samples of fungi, while the other oils had a less pronounced effect, which could be improved by adjusting the dosage [59]. Colletotrichum musae and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides isol

ated from mango and banana fru

lar [its were treated with eugenol and rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), eucalyptus (Eucalyptus citriodora), and copaiba (Copaifera langsdorffii) 28essential ]oils.

EntretantoRosemary and eucalyptus essential oils inhibited the growth of C. musae,

copa

espécieiba oil was efficient against C. gloeosporioides, a

nd eugeno

infectar folhal showed antifungal activity against both species [60]. Some studies

related

e amora-preta, por exemplo, forma vesículas especializadas sobre ou dent the antifungal activity of secondary plant metabolites to their penetration into the hyphal wall, damaging the lipoproteins of the cytoplasmic membrane and leading to cytoplasmic extravasation, as well as emptying, dehydration of hyphae, and the presence of filaments [60,61].

The infor

matio

dos estômatos, permitindo que as hifas entrem nas folhas [n presented in this section demonstrates the possible application of essential oils as biofungicides. The complex chemical profile and specific characteristics of the molecules present in EOs 29enable ].their Em outro caso,antimicrobial effect. Although further elucidation regarding the mechanism of action against the C. olletorbiculareprtrichum genus sho

uld

uziram um apressório para romper a superfície da planta e fazer com que enz be established, there is a robust body of data indicating the fungicidal properties of EOs. The versatility of essential oils, as well as the chemical variety present in these oils, can be an alternative to reduce the barriers imposed by the complex lifestyle of the genus Colletotrichum.

5. Active Films and Coatings

Fi

lm

as líticas digerisses and coatings are thin layers, usually up to 0.3 mm thick, that have been used for centuries to protect foods from structural damage and nutritional losses [62]. Film

s a

cutícula e a parede celular, permitindo a adesão dos conídios dessa espécie [nd coatings can improve the physical strength of foods and can act as a barrier against gases and water vapor, decrease moisture migration, control microbial growth, reduce changes caused by light and oxygen, and improve visual and tactile characteristics. Thus, they 30are ].

Apóus

ually a

penetração, diferentes espéciepplied to increase the quality and shelf life of food products, protecting them from physical, chemical, and biological deterioration [63,64].

Biobas

ed po

dem iniciar um processo hemibiotrófico intlymers commonly used in film and coating formulations are extracted from plants, animals, or microorganisms. Hydrocolloids are easily applied as biopolymers, with proteins and polysaccharides being the most used [65,66]. Some for

mula

celular ou subcuticular, gerando uma fase biotrófica assintomática sem morte celulartions can be added with oils or fats, such as triglycerides, waxes, free fatty acids, and vegetable oils, to improve the water vapor barrier properties, due to the hydrophobic nature of these materials. Biopolymer-based coatings have been applied to fruits such as mango, apricot, and papaya, promoting an increase in their shelf life by preserving texture and reducing weight loss and respiration rate [67,68,69].

The Pincorporation o

steriormente, os fungos podem entrar na fase necrótica, onde hiff substances with antimicrobial potential in the production of coatings and films has been suggested as a strategy to maximize their benefits to the quality and safety of fresh products and further increase their shelf life [70,71]. These a

sre the s

ecundárias crescem no espaço intracelular e intercelular, que secretam enzimas degradantes da parede, levando à morte celular [o-called “active films and coatings”, which can promote the controlled release of active compounds. Depending on the application, migration rates can be reduced, immediate, extended, and specific or absent. Chemical bonds between the materials and the active substance must be considered, as well as the environmental factors that may regulate the migration process of the 23active ]compound.

Além desse mecanismo, algumas espécies podem iniciar oMany active compounds of different natures can be applied to form the active packaging, the most common being fertilizers, repellents, pesticides, antimicrobials, antioxidants, bioactive nutraceuticals, paints, and flavors [53,71].

As pr

evio

cesso de infecção necrotrófica intramural subcutânea, onde os fungos crescem sobusly mentioned, EOs are substances with a broad spectrum of activity against fungi and bacteria, which can be added to films and coatings to increase the shelf life of foods [72]. EOs a

re cutícula entre as paredes perihighly volatile, unstable, and hydrophobic; therefore, they are usually added in the form of emulsions, ensuring uniform dispersion [73].

The use of c

loatin

al e anticlinal sem a penetração de progs and active films containing essential oil emulsions to control phytopathogens has been explored by several researchers [74,75]. Cassava st

arch films inco

plastos [rporated with clove essential oil 28were ,applied 31to ].bananas Infecções causadasand showed efficient antifungal activity against por C.olletotrichum gloeosporioidesjá and Colletotrichum musae [76]. Most studies fsho

ram relatados como hemibiotróficos intracelulares em goiabeiras, onde vesículas e hifas de infecção foram formadas na célula epidérmica inicialmente infectada [wed promising results, encouraging different research groups to continue improving the methods and techniques related to the formulation of these packages. An analysis of these studies will make it possible to understand the current results while presenting new alternatives for even more auspicious results. Although the future seems promising for this technology, the lack of machinery to produce films and coatings with high productivity and low energy consumption is a major challenge for scaling up this technology. Additionally, the mechanical strength and barrier properties of active packings need improvements 32to ].

Acompete wi

nteração entre o hospedeiro e o agenth the long-established petroleum-derived plastics; furthermore, as a new technology, films and coatings should prove their safety to conquer consumer acceptance [62].

6. Emulsions

Despite

mall thei

crobiológico durr benefits, the use of EOs is a challenge, due to their lipophilic, volatile, and highly oxidizable nature [77]. These cha

nracteristics hamper t

e o desenvolvimento da antracnose é complexa e dinâmica. Os dhe direct application of essential oils in foods, reducing their biological activity and promoting undesirable organoleptic alterations. A delivery system compatible with food applications can minimize these impacts and retain the biological activity of EOs [78]. In thi

fs se

rentes estilos de vida que esse gênero pode adotar tornam ainda mais difícil o tratamentonse, emulsions are easy-to-formulate delivery systems that can be applied to protect EOs against environmental factors and to ensure the effectiveness of their application.

6.1. Conventional Emulsions

An e

fmulsi

caz e econômico dessa doença em frutas tropicais e subtropicais [on consists of two immiscible liquids, with one of them dispersed as small spherical droplets in the other. Emulsions formed by water and oil and can mainly be classified as water-in-oil (w/o) emulsions (water 25droplets ]. Adis

perdas por contaminação podem impactar todo o processo produtivo, levapersed in an oil phase) or oil-in-water emulsions (oil droplets dispersed in a water phase). They have relevant use in several areas, including the food sector. In addition to being present in many natural or processed foods, they are also used in delivery systems for functional compounds such as vitamins, nutraceuticals, aroma, flavor, color, and preservatives [13]. Emulsion

systems enable the ad

o a prejuízos econômicosministration of active compounds through encapsulation, which can preserve and control the release of functional ingredients, improving efficiency, handling, and/or stability [

33 79].

Some Ostudies

riscos de controle e mhave incorporated EO emulsions in active coatings and films, exploring their antimicrobial activity to prevent anthracnose symptoms in different fruits. Emulsified essential oils from Allium sativum, Copaifera langsdorfii, Cinnamomum zeylanicum, an

d Eugenia caryophyllata we

jre inco

associados à infecção porrporated into polymeric coatings to control the symptoms caused by Colletotrichum musae in bananas

ão pontos fundamentais para evit. All treatments reduced the incidence, lesions, and disease severity [80]. The progression of a

nthr

a diacnose in papayas caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Colletotrichum brevisporum was

p

ersão do frevented by applying chitosan coatings added with essential oil of Mentha piperita L. or Mentha × villosa Hu

ds emulsion

go e as. The formulations conta

minaçãoining 5 mg/mL of chitosan and 0.6 μL/mL of deMentha piperita oil o

utr

as fr 1.6 μL/mL of Mentha × villosa Hu

tads

.

3. Tratamentos Convencionais para Prevenção da Antracnose

F oil r

edu

tas tropicaisced the development of lesions similarly or superiorly to commercial fungicides [81]. The

subtropicais são produzidas para subsistência e distin vitro and in vivo potential of cassava starch films incorporated with lemongrass, thyme, and oregano essential oils was evaluated against Colletotrichum musae fr

om bananas. Oregano oi

buição local há muitos anosl inhibited mycelial growth and the complete in vitro germination of C. musae conidia.

ILemon

vestimentos em tecnologia e melhorias nas congrass and thyme essential oils and two percent and three percent cassava starch films, as well as their combination, were effective in reducing and preventing anthracnose lesions in banana fruits [82]. All these studi

ções

de transporte e armazenamento possibilitsuggest that the use of emulsified essential oils incorporated into coatings or films can inhibit the growth of anthracnose-causing fungus in tropical fruits.

La

tely, severa

m a comercialização global dessas frutas. O Hemisfério Sul passou por mudançal studies have shown that the droplet size strongly affects the bioactivity of essential oil emulsions. A nanoemulsion is a scarcely explored strategy in combating the Colletotrichum genus

, significativas em seus processos produtivos para atingir o padrão ideal de exportação de frutas pbut recent studies have indicated that its benefits can surpass those of macroemulsions, depending on the materials used and the application. On a nanometric scale, emulsions may have higher bioactivity and greater stability, and they may cause little change in the physicochemical characteristics of fruits [78,83].

6.2. Nanoemulsions

Conventiona

ral o Hemisfério Norte [emulsions are characterized by an 34].average Ndro

entanto, alguns desafios como a falta deplet radius ranging between 100 nm and 100 µm, and nanoemulsions have an average droplet radius ranging between 10 and 100 nm [84]. tRe

cnologia e infraestrutura, alta infestação de insetos, crescimento microbiano indesejado, aparecimento de lesões e manchducing droplets to a nanometric scale decreases the attractive forces acting on the droplets, consequently avoiding aggregation and coalescence. Furthermore, the conditions of physical stability are governed by Brownian motion, which ends up dominating the gravitational forces. As a result of the different forces acting on the droplets, nanoemulsions are more stable than emulsions [10,13,78].

Na

noemuls

devido ao manuseio ouions are dispersions created with the aid of an energy source, which come from methods classified as high- or low-energy [85]. Low-energy met

ransporte inadequado e prevalência de altashods are characterized by the spontaneous formation of small oil droplets, changing the solutions or the environmental conditions in which they are inserted. Phase inversion temperatur

as e umidade ainda dificultam o processo de comercialização. Nesse contexto, a prevenção de doenças pós-cole, phase inversion composition, membrane emulsion, spontaneous emulsification, and solvent displacement/evaporation are some of the methods for producing nanoemulsions under low-energy conditions. These methods have some disadvantages, such as the use of large amounts of solvent [86] or synthe

ti

ta éc surfactants [87] and dif

undamental paficulties in operating with large volumes of nanoemulsion solution [88].

High-ener

agy methods use m

anter o comércio de frutas e reduzir perdas.

3.1. Tratamentos Físicos

Dechanical devices to create intense disruptive forces to disrupt the oil and water phases, forming tiny droplets. Methods such as rotor–stator, ultrasound, and microfluidic homogenization or high-pressure valves are the most frequ

ently applied to for

ante a fase de pós-colheita, alguns tratamentos físicos e químicos tradicionam nanoemulsions in high-energy systems. The disadvantages of these methods may be associated with long processing times, especially in high-pressure systems in which many cycles should be employed to form a homogeneous nanoemulsion, promoting lipid droplet coalescence and temperature increase during production [83]. Hi

sgh podem ser aplicados para controlar os sintomas da antracnose. Alvindia e Acda [temperatures are critical for EOs during nanoemulsion formation processes, because the compounds present in these oils are volatile and sensitive to temperature increases. In this context, it is worth mentioning that when high-energy methods are applied, 35it ]is avaliaram os efeitos da anecessary to evaluate the retention of essential oil at the end of the process and, thus, to quantify the possible losses during the formation of the nanoemulsion.

6.3. Advantages of Using Nanoemulsions over Conventional Methods

As the dropl

et si

cação de água quente em mangueiras causadoras de antracnoze decreases, the biological activity of the compounds encapsulated in the nanoemulsion system increases. This is because the transport of active molecules across cell membranes is performed more easily, and there is a greater relationship between surface and volume, impacting reactivity [10]. According to Dons

í and Fe

.rrari [78], Nthe

ste estudo, o tratamento a 53 °C por 20 min te fusion of the small droplets of the nanoemulsions with the phospholipid bilayer of the microorganisms facilitates their access through the membrane surface, allowing their rupture and leading to cell death. Anwer et al. [89] observe

d efeito significativo that clove essential oil nanoemulsion showed greater antimicrobial activity against several microorganisms (Bacillus subtilis, Staphyloccocus aureus, Proteus vulgaris, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an

d Klebsiella pneumoniae) when compa

red redução da gto pure essential oil. Pongsumpun, Iwamoto, and Siripatrawan [90] re

por

minação de eted that cinnamon essential oil nanoemulsions showed greater activity against several fungi (Aspergillus niger, Rhizopus arrhizus, Penicillium sp

oros., deand Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) após 48 h, prthan the conventional emulsion, with inhibition halos more than twofold larger.

Nanoe

muls

ervando a qualidade dos frutos. No entanto, a grande quantidade de água uions can exhibit an apolar phase and droplet size-dependent optical transparency. Systems with a droplet size below 40 nm usually form a transparent solution, whereas droplets in the range from 40 to 100 nm can result in turbid nanoemulsions (depending on the content of the nonpolar compound); lastly, emulsions with droplets above 100 nm are usually white due to significant multiple scattering [78,91]. Determining t

hi

lizada é uma desvants relationship between droplet size and nanoemulsion color is critical, as color is an important attribute when applying films and coatings on foods [92].

Na

gnoem

desse tipo de tratamento.

Outulsions have been used as encapsulation and delivery methods for bioactive compounds, as they are kinetically mor

oe s

tratamentos físicos foram table than macroemulsions and less susceptible to coalescence, cream formation, flocculation, and sedimentation [93]. They ca

vn be a

liados em estudos recentes. Fischer et ai. [pplied to extend the shelf life of foods, improving the stability and solubility of the encapsulated active compound. Furthermore, in nanoemulsified systems, the active compound 36does ]not usaram radiação UV-C parinteract with environmental factors, and its release is controlled and prolonged [94,95].

Na

noemulsions c

ontrolar sintomas de antracnose e podan provide droplets in sizes up to 200 nm, facilitating the interaction between the active compound and the fungus membrane. In this process, the availability, retention, and preservation of essential oils are improved [73]. Fur

thermore, i

dão do caule em frutos de abacate inoculados comn nanoemulsions, EOs behave differently than in simple emulsions. Nanoemulsified EOs can have a sustained release, prolonging the time of action against microorganisms. C. glThe essential oil of Grammoeosporioidesciadium pterocarpum Bioss.

As doses aplicadas de radiação UV-C (0,34–0,72 kJ·mwas incorporated in the free form and nanoemulsified in films formed with whey protein isolate. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity tests showed that films formed with nanoemulsions had significantly higher results than those formed −2with )free não foram efetivas em reduzir a ocorrência da doença. Ao contrário, aplicandessential oil, confirming the distinct retention and release pattern of nanoemulsified oils in films described previously. In this case, the film with the nanoemulsified EO continuously released its EO content for a longer period of time, and the film with free EO discharged its EO content acutely in the medium [96].

Ano

ther uma dose maior de raadvantage of using nanoemulsions is that when applied to films, there is better maintenance of the original matrix arrangement of the films because of the droplets’ nanometric diameter [97]. The nanoemulsified

ci

ação (3,0 e 4,0 kJ·mnnamon essential oil was incorporated into pullulan-based films. The −2small ),diameter Wanasinghe e Damunupola [and uniform size distribution of the droplets formed in the nanoemulsion were associated with 37]an increas

uprimiu com ed EO retention rate and improved microbial activity of the film [98]. Thes

e stu

cesso os sintomas de andies corroborated the potential to expand the shelf life and quality of tropical fruits through the application of embedded EO nanoemulsion films and coatings.

Recent

r

acnose em tomatesesearchers have developed active films and coatings incorporated with EO nanoemulsions to improve the shelf life of many foods [99,100].

NA co

entanto, esses ating formed with sodium alginate and eugenol, carvacrol, and cinnamaldehyde nanoemulsion was applied to Nanfeng mandarins. The result

ados devems of this study showed an inhibitory effect on Penicillium digitatum growth and sbetter

avaliados com cautestability of the physical parameters in treated fruits compared to untreated ones [100]. A thymol

na

, pois os autonoemulsion incorporated in films prepared with chitosan and quinoa protein showed inhibition of Botrytis cinerea gr

owth in che

s rry tomatoes [101].

7. Current Scenario: Essential Oils in Active Film and Coating Formulations

Currently, sobciety is servaram a presença de compostos antifúngicos na casca do tomate. Além disso, a radiação ainda é vista como um problema para os consumidores. Embora thowing great concern for the loss/waste of fruits and vegetables, as these are essential components in daily human diets around the world. Tropical fruits are highly perishable and suffer from diseases that cause significant losses in both production and marketing. Anthracnose is a very common disease that can be found in a wide variety of tropical fruits. The wrong management of anthracnose in some countries could promote a deleterious economic impact. Treating anthracnose and controlling postharvest symptoms can bring great improvements to the production of various fruits.

The currenha impacto ambiental mít scenario of studies using EOs for the treatment of anthracnose reveals the concern of scientists in seeking clean and sustainable methods for this problem. More efficient and less aggressive treatments are needed at this time. The articles cited in Table 1 indimo, a falta de informações sobre possíveis alterações na alimentação e,cated promising results regarding in vitro and/or fruit application tests. Therefore, this review proposes a deeper investigation of the application of nanoemulsified EOs for the treatment of anthracnose. The perspectives for the future are encouraging, and the knowledge gaps described in this review should be elucidated in the near future by robust and well-structured research. In this section, a survey of the main gaps and methods applied so far for the treatment of anthracnose with EOs is carried out.

A co

mpilation

sequentemente, os possíveis impactos desse tip of the most relevant studies found since the early 2000s, focusing on the use of essential oils incorporated or not into films and coatings for the treatment of fruits with anthracnose, is presented in Table 1. Fro

m de tratamento na saúde humana continuam sendo as princithese data, it can be concluded that essential oils have a high potential to combat anthracnose symptoms in tropical fruits. All studies had in vitro tests reporting the antifungal effect of the oils against the Colletotrichum sp

aeci

s barreiras para a aceitação desse método [es tested. Furthermore, most studies used essential oils with direct application on the surface of the fruit or in the form of emulsions (without using high- or low-energy methods to produce 38them).

The ].

3.2. Tratamentos Químicos

Algstu

dies shown

in Table 1 us

ed tratamentos químicos são aplicados para reduzir os sintomas da antracnose em frutas, mas a maioria é tóxica ou menos eficiente ao longo do tempo à medida que aumenta a resistência do patógeno. Vieira e cols. [essential oils from different sources or major components of EOs, with fungicidal and/or fungistatic capacity. Studies using active films and coatings for the treatment of anthracnose still focused on direct applications, spraying, or simple emulsions of EOs. The application of nanotechnology was not considered in most (approximately 80%) of these articles. Among the articles that considered the use of nanotechnology for the treatment of anthracnose and that used nanoemulsified essential oils, only two applied a nanoemulsion in films or coatings. Neither of these two studies presented a sensory evaluation of the fruits. Data on the sensory analysis of tropical fruits that were subjected to post-harvest treatment with films and active coatings are still scarce, especially for the treatment of anthracnose. Although nanoemulsions require less use of EOs, they 39are ]rich avaliaram a eficácia do tiofanato-metílico, fungicida frin aromatic compounds that can provide significant changes in the original characteristics of the fruit, which may or may not be acceptable to consumers. Sensory evaluation is an effective tool to evaluate the influence of active packings on the sensory characteristics of tropical fruits, such as alterations in the taste, odor, and general appearance of the fruits.

Whe

qn evaluating the stu

entemente utilizado no controle da Sigatoka-negra, sobre o crescimento dedies for the treatment of anthracnose using nanoemulsified EOs presented in this review, some gaps were noticed. Did the application of nanotechnology to form emulsions with even smaller droplets have a significant effect on reducing fungal growth? Did the droplet size remain nanometric after the nanoemulsions were added to film and coating solutions? These questions are important to justify the use of nanotechnology as a viable alternative to the treatment of anthracnose. Colletotrichum musaeOf the ,eight carticles (Table 1) tha

t us

ador da antracnose em bananased nanoemulsified EOs, only one presented data on the antifungal effect of the nanoemulsion in relation to the crude emulsion [90].

SeuThis result

ados sugeriram uma potencial resistência de could elucidate the cost–benefit assessment of the process, as it justifies the use of energy-generating mechanisms, which require greater investment, for nanoemulsion production. In addition, the evaluation of droplet size after coating or film production would guarantee the presence of Colletotrichum musaeEO na

o tiofanato-metilnoemulsions in the final and most important stages of active packing development (application and storage). In the two studies [102,

103] lthat presente

vando à ineficácia do tratamentod EO nanoemulsions embedded in film or coating, there was no evaluation of the droplet size after the production of film/coating-forming solutions.

The Tdata presented i

n Table 1 demonstra

bte

ndazol apresentou baixo controle do crescimento d studies that achieved highly promising results regarding the inhibition of fungal growth and a consequent reduction in anthracnose symptoms. Regarding the in vivo results, the authors reported the

Colletotrichum gloeosporioidesinhibition emof m

amão, enquanto os fycelial growth, the inhibition of fungal growth, and a reduction in lesions. Generally, the main effect in vitro was fungicida

s imazalil, procloraz, propiconazoll, while that in vivo was fungistatic. Results in vivo indicated the high power of infection of the fungus and its resistance to the treatments tested. Some studies showed promising results with the use of EOs incorporated into active coatings to minimize the symptoms of anthracnose [81,82,104,105]. Howe

tebuconazol apresentaram efeiver, these studies did not use nanoemulsified EOs. Most of the articles that produced nanoemulsions (reported in Table 1) wit

oh the positivo ao interromper a germinaçãoobjective of inhibiting the growth of different species of the genus deEsporos de Colletotrichum gloeosporioides quapresen

do aplicado a 50 ppm [ted only in vitro results. This demonstrates how much improvement is needed 40for ].this Mesmo com retechnology to reach the consumer market.

From the data su

lmmarized in Table 1, it

ca

dos satisfatórios, o uso repetido e continuado desses agrotóxicos pode alterar o equilíbrio dos ecossistemas, aumentar a incidência e severidade de doençn be observed that the use of an active coating/film has not yet been exhaustively evaluated. Films and coatings are made of natural and biodegradable products that can provide greater stability to the fruit during storage. The respiratory process of fruits continues after harvest, and films and coatings act as a physical barrier against gas and water vapor exchange, delaying the ripening and deterioration processes [97,106]. These fa

ctors

e ainda selecionar isolados res, associated with the antifungal effect of EOs against phytopathogens, can guarantee an increase in shelf life, minimizing the symptoms of fruits infected with the genus Colletotrichum.

The potential benefits of treating anthracnose with nanoemulsified EOs incorporated into films or coatings are numerous. However, there are major challenges to overcome in order for this treatment to become an alternative to conventional anthracnose treatments. The choice of EOs considering their properties, the definition of the production method of nanoemulsions, and the selection of the best polymer for film and coating formation are still the main research questions in this area. This reveals the absence of robust studies involving the application of nanoemulsified EOs in films and coatings for the control of anthracnose symptoms in tropical fruits.

Despi

ste

ntes a esses compostos químicos [ 41 ].

Um the great potential of EOs and the noticeable improvement in their properties when they are in the form of nanoemulsions, furt

her

atamento bem-sucedido para o controle da ant data is needed to confirm nanoemulsion superiority compared to crude emulsion and pure oil. Studies with consistent results on the reduction in anthracnose

deve considerar os impactos na saúde ambiental. Os recursos devem ser selecionados para manter seu equilíbrio no meio asymptoms in tropical fruits, especially those that are superior to conventional treatments, will be important to justify investments in this area. The evaluation of the commercial viability of the treatment using films and coatings should be considered. Tropical fruits are generally produced on a large scale to meet local consumption and export demands. Therefore, it would be interesting that future studies replicate a pilot-scale film/coating production; this type of work using highly commercialized fruits should bring awareness regarding technology viability, reality of the productive market, and the consumption profile.

Fromb thiente, evitando o desperdício, sem causar poluição ou danos futuros. Os tratamentos disponíveis para o controle dos sintomas da ants review, the importance of future studies focusing on improving the formulation of nanoemulsions, as well as their application in tropical fruits, is clear. Evaluations of fruit quality and sensory characteristics, as well as the reduction in anthracnose symptoms, are essential to explain the use of coating-forming solutions or films loaded with nanoemulsions. With the increase in consumption of essential oils around the world, the regulation of these oils has been carried out little by little in partnership between organizations and governments. This scenario favors the use of EOs for the treatment of anthracnose ainda enfrentam barreiras, que podem inviabilizá-los ou ineficaz. A utfrom a commercial and a food safety point of view. In this sense, future studies that focus on the development of EO nanoemulsions incorporated in films and coatings can be an attractive and innovative alternative for the tropical fruit market.

8. Conclusions

Thils revização de agentes químicos ou físicos para reduzir o crescimento do gêneroew has demonstrated that essential oil-based active films or coatings have been successful in treating anthracnose in many tropical fruits. The inhibition of the growth of the Colletotrichum dgeve atender a critérios de segurança e preservação ambiental. Portanto, um número crescente de estudos tem investigado potenciais pesticidas naturais capazes de garantir a integridade das frutas, bem como a segurança e a redução de perdanus in vitro and in vivo was a noticeable reality in almost all studies that used the active film or coating as a treatment. Studies showed that the application of essential oils in the form of nanoemulsions improved their antifungal potential, increased their efficacy, and reduced the amount needed, which are advantageous attributes from the sensory and economic points of view. However, to date, only a few recent studies have applied nanoemulsions for the treatment of anthracnose. In this way, nanoemulsions represent a reality that can be further explored in the area of food preservation, especially for the treatment of anthracnose. The advantages presented in this review reinforce the potential of nanoemulsions to improve the results already obtained and generate unprecedented results in inhibiting fungal growth and disease development. However, further studies are still needed for a cost–benefit analysis of this technology and to confirm the superiority and viability of EOs nanoemulsions incorporated with films and coatings compared to conventional treatments.