Plants are constantly exposed to both biotic and abiotic stresses which limit their growth and development and reduce productivity. In order to tolerate them, plants initiate a multitude of stress-specific responses which modulate different physiological, molecular and cellular mechanisms. The microbial community in the rhizosphere (known as the rhizomicrobiome) undergoes intraspecific as well as interspecific interaction and signaling. The rhizomicrobiome, as biostimulants, play a pivotal role in stimulating the growth of plants and providing resilience against abiotic stress. Such rhizobacteria which promote the development of plants and increase their yield and immunity are known as PGPR (plant growth promoting rhizobacteria). On the basis of contact, they are classified into two categories, extracellular (in soil around root, root surface and cellular space) and intracellular (nitrogen-fixing bacteria). They show their effects on plant growth directly (i.e., in absence of pathogens) or indirectly. Generally, they make their niche in concentrated form around roots, as the latter exude several nutrients, such as amino acids, lipids, proteins, etc. Rhizobacteria build a special symbiotic relationship with the plant or a section of the plant’s inner tissues. There are free-living PGPRs with the potential to work as biofertilizers. Additionally, studies show that PGPRs can ameliorate the effect of abiotic stresses and help in enhanced growth and development of plants producing therapeutically important compounds.

- PGPRs

- biostimulants

- phytohormones

- abiotic stress

1. Introduction

2. Amelioration of Abiotic Stress in Medicinal Plants

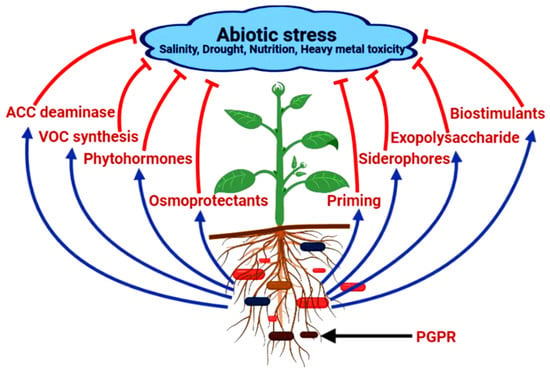

Due to their sessile nature, plants have to endure various types of abiotic stresses such as drought, heat, toxic heavy metals, salinity, etc. which impede their growth and development. They obtrude injurious effects on various physiological processes such as photosynthesis, floral development, and seed germination, as well as induce stomatal closure, etc. [26,27,28,29,30]. The quality of medicinal plants is defined by their active ingredients and their concentrations. However, under stressed conditions, the metabolite constitution of these plants gets altered. In a study on effect of drought stress on Thymus vulgaris, it was that found that stress affects the different compound levels of metabolite of medicinal plants such as γ-terpinene, carvacrol, p-cymene, etc. as well as decreasing essential oils [31]. To overcome the drought stress, medicinal plants produce bioactive ingredients and induce genetic factors. Salinity causes water reduction as well ionic toxicity which directly affects the growth reduction due to nutrient deficiency in medicinal plants such as Matricaria necati, Aloe vera, and T. vulgaris. Salinity also increases the essential oils contents in medicinal plants such as T. vulgaris, Salvia officinalis, etc. Heavy metal stress causes protein denaturation and lipid peroxidation by interacting with phytochelatins, organic molecules and glutathione. High concentration of nickel reduces the production of hypericin and hyperforin in Hypericum perforatum. Ramankutty et al. [32] reported that approximately 12% of the earth’s surface can be used for the agricultural practices due to cold stress. Cold stress affects the physiological, metabolic and genetic processes in plants. Under cold stress, plants produce protective compounds like inositol, sorbitol, rebitol, sucrose, trehalose, raffineur, glucose, proline, glycinebetaine, and phenolic compounds. Under heat stress, plants increase the activity of antioxidative enzymes to remove reactive oxygen species. High temperature induces the production of pseudohypericin, hypericin and hyperforin in medicinal plants. PGPR employs various methods for tackling the stress conditions and promoting the growth and development of plants (Figure 1).

2.1. Production of ACC (1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylate) Deaminase

Ethylene has been considered to be one of the most important plant hormone(s) which is secreted during stress conditions. However, the elevated level of ethylene or “stress ethylene” in plants has been found to have a negative role in plant growth. In a study, it was found that overproduction of ethylene in Arabidopsis thaliana resulted in dwarfness of plant and the inhibition of normal growth [33]. PGPR plays an imperative role by inhibiting the negative effects of ethylene stress [34]. PGPR with enhanced ACC deaminase activity reduces the concentration of endogenous ethylene by cleaving 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate, the precursor of ethylene, in ammonia and α-ketobutyrate [34,35,36]. Zarei and colleagues [37] studied sweet corn (Zea mays L. var. saccharata) and concluded that under osmotic stress/drought condition, crop yield could be increased by using P. fluorescens. Under stress conditions, it enhanced the nutrient acquisition, reduced the endogenous ethylene concentration and ameliorated physiological condition of plants to increase the overall productivity of the plant [37]. ACC deaminase production in PGPR Achromobacter piechaudii ARV8 elevated the dry and fresh weights in pepper and tomato under water stress [38,39].2.2. Secretion of Osmoprotectants (Proline, Choline and Trehalose)

In the course of evolution in the terrestrial environment, plants and bacteria developed symbiotic relationships to fulfill different essential requirements for survival. One of the major benefits which plants derive from bacteria is protection against various environmental abiotic stresses. Under osmolality fluctuation conditions in the environment, microbes accumulate large quantities of solutes in their cytosol which acts as an osmoprotectant [42]. During osmotic stress, synthesis of solutes like proline, trehalose and choline is found to be quicker in microbes than in plants. During salinity and drought stress, these solutes are absorbed by plant roots and increase the osmolyte concentration in plants, and ameliorate stress conditions [43,44,45]. In a whole genome study on eight different PGPR isolated from halophytes, it was found that they contain genes which play crucial roles in abiotic stress response [46]. Environmental perturbations such as drought stress lead to decreases in metabolite concentration in plants, and thus hamper the normal physiological process. Khan et al. [47], in their studies demonstrated in chickpeas that, under stressed conditions, the level of sugar, amino acid (histidine, tyrosine, and methionine) and some organic acids like tartaric acid and citric acid were decreased. Decreased sugar levels lead to reduced chlorophyll content and hence resulted in dropped photosynthetic efficiency of plants. However, treating the chickpea plants with PGPR and PGR consortium led to increased sugar levels in plants and consequently, attainment of the normal photosynthetic efficiency of the plants [47].2.3. Secretion of Volatile Compounds for Tolerance against Stress

PGPR stimulates tolerance against stress in plants in various ways. One of the most common mechanisms by which PGPR mediates abiotic stress tolerance in plants is production of volatile as well as non-volatile compounds which facilitate plant development. Salt stress conditions lead to increased hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and reactive oxygen species (ROS; O2−). ROS is an important signal molecule at low concentration and plays an important role in programmed cell death, regulation of cell cycle, etc. but at higher concentration, it confers deleterious effects on plants. It leads to damage to cells and overall growth of plants [50] and inhibits development of roots by reducing the size of root meristems [51]. However, treating plants with PGPR leads to reduced levels of ROS and alleviates salt stress in plants. JZ-GX1 produced volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that induced activity of antioxidant enzymes in plants and prevented oxidative damage caused by ROS through enzymatic and non-enzymatic systems [49]. Based on present research findings, under salt stress Azotobacter enhances the antioxidative enzyme activity by inhibiting H2O2 and malondialdehyde in Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (medicinal and industrial plant) to relieve salt stress [52]. It was also observed that treating the plants with PGPR led to decreased levels of malondialdehyde, which is an indicator of membrane disintegration and plasma membrane damage [53].

Salinity stress results in increased concentration of sodium (Na+) ions and Na+/K+ imbalance into cytoplasm. Potassium (K+) ion is important for functioning of plant metabolism and overall physiological process. K+ is considered a “master switch” which regulates the transition from “normal state” to “hibernated state” during stress conditions [54,55]. Previous studies demonstrate that the high K+/Na+ cytosolic levels in plants are a prerequisite for salt tolerance. However, due to high physico-chemical similarities between K+ and Na+, Na+ competes with binding sites of K+ ions, and interrupts the normal functioning of enzymes. Volatile compounds secreted by certain PGPRs are shown to reduce the Na+ level in plant roots and shoots. HKT (high affinity K+ transporter) is a member of IMPs (integral membrane proteins) and plays a crucial role in transport of cation across plasma membranes in plant cells [56]. It plays a pivotal role in plants under salt stress. Sodium transporter (HKT) is expressed in xylem parenchyma and is responsible for exclusion of Na+ from leaves by removing Na+ from xylem sap [57,58]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, it was observed that the plant exposed to Bacillus subtilis GB03 VOCs accumulated less Na+ in both root and shoots. AtHKT restricts Na+ into roots, which leads to higher root-to-shoot Na+ ratio. B. subtilis GB03 released VOCs, repressing the activity of AtHKT in root while increasing its activity in shoot. This mechanism of recirculation of Na+ from shoot to root by modulating the activity of AtHKT explains the role of VOCs in alleviating salt stress [48,57].