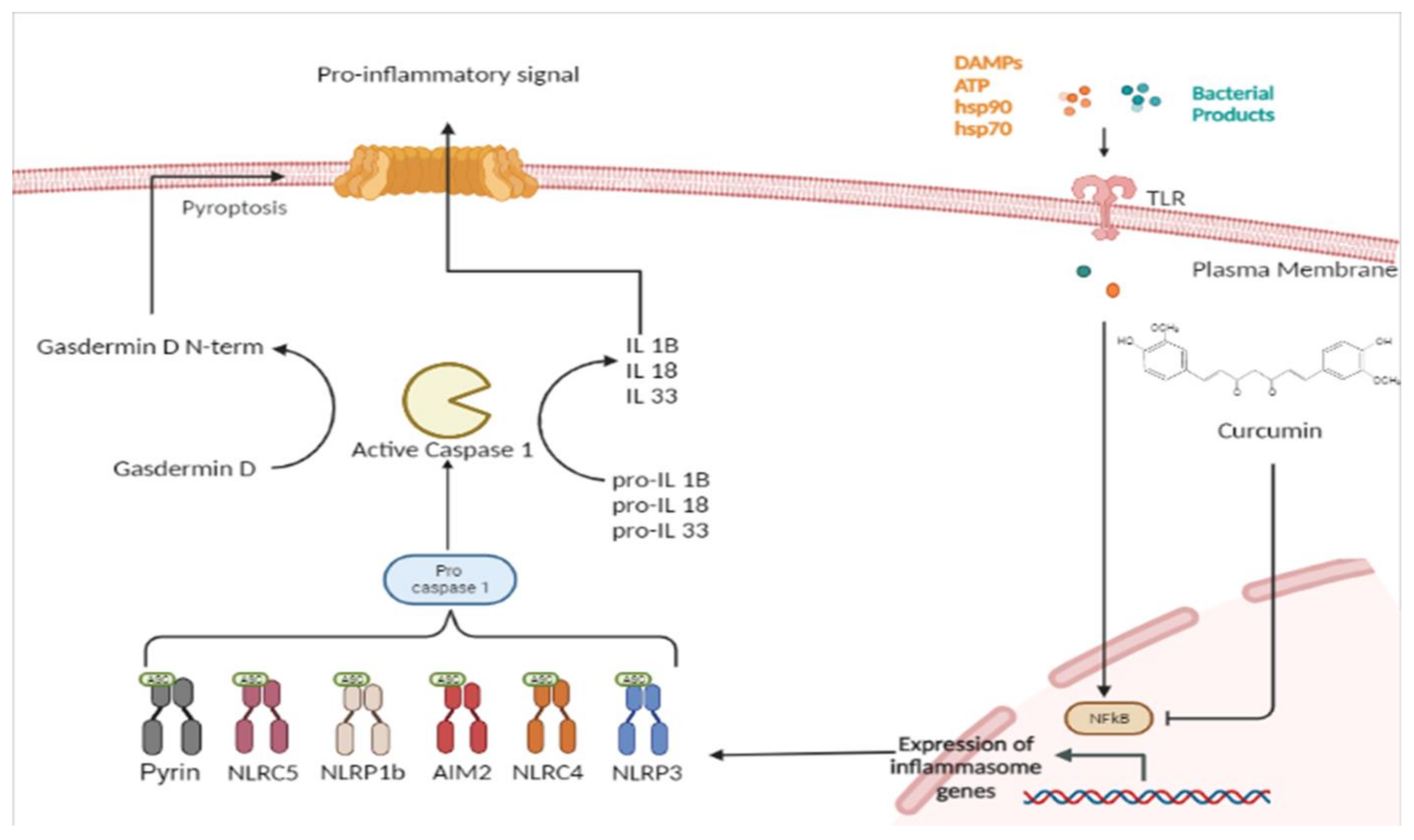

Curcumin, a traditional Chinese medicine extracted from natural plant rhizomes, has become a candidate drug for the treatment of different diseases due to its anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities. Curcumin is generally beneficial to human health, with anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties, as well as antitumor and immune regulation properties. Inflammasomes are NLR family, pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) proteins that are active in response to a variety of stress signals and promote the proteolytic conversion of pro-interleukin-1β and pro-interleukin-18 to active forms, which are central mediators of the inflammatory response; inflammasomes can also induce pyroptosis, a type of cell death. The NLRP3 protein is involved in a variety of inflammatory pathologies, including neurological and autoimmune disorders, lung diseases, atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and many others. Different functional foods may have preventive and therapeutic effects in a wide range of pathologies in which inflammasome protein results activated. In this review, we have focused on curcumin and evidenced its therapeutic potential in inflammatory diseases such as neurodegenerative diseases, respiratory diseases and arthritis by acting on inflammasome.

- curcumin

- natural flavonoid

- inflammasome

1. Introduction

2. Inflammasome

Inflammasomes are multimeric protein complexes that are widely expressed in the cytoplasm of various cell types, including immune and non-immune cells [14]. Inflammasomes mediate the host’s innate immune responses to microbial infection and cellular damage. Cells are activated through the intervention of germline-encoded pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) on the surface of the cell membrane. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are recognized by PRRs. Examples of conserved microbial factors detected by PRRs include the bacterial secretion system, microbial nucleic acids, and elements of the microbial cell wall. PRRs are also triggered by endogenous danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) generated in the setting of cellular injury or tissue damage [15], such as ATP, uric acid crystals, heat-shock proteins hsp70 and hsp90, and the high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) [16]. The binding between PRRs and PAMPs or DAMPs induces NF-κB activation and the expression of the inflammasome [17]. Inflammasome protein complexes are classified into canonical and non-canonical. The classification depends on the activation of cysteinyl and the mode of activation of cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase (Caspase) during inflammasome formation. Canonical inflammasomes are constructed by the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD) leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-containing protein receptors (NLRs). The canonical inflammasomes include Nlrp3, Nlrp1b, Nlrc4, the ALR member absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2), and pyrin. [18]. These assemble canonical inflammasomes that promote activation of the cysteine protease caspase-1 (Figure 1). The non-canonical inflammasome promotes activation of procaspase-11 (caspase-4 and caspase-5 in human). Recently, extracellular lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been found to trigger the activation of the non-canonical inflammasome. LPS induces the expression of pro-IL-1β and NLRP3 via the TLR4-MyD88-dependent pathway and type I interferon via the TLR4-TRIF-dependent pathway. Type I interferon results in a feedback loop and activates type I interferon receptor (IFNAR) to induce caspase-11 expression [19].

References

- Hewlings, S.J.; Kalman, D.S. Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017, 6, 92–98.

- Benameur, T.; Soleti, R.; Panaro, M.; La Torre, M.; Monda, V.; Messina, G.; Porro, C. Curcumin as Prospective Anti-Aging Natural Compound: Focus on Brain. Molecules 2021, 26, 4794.

- Chilelli, N.C.; Ragazzi, E.; Valentini, R.; Cosma, C.; Ferraresso, S.; Lapolla, A.; Sartore, G. Curcumin and Boswellia serrata Modulate the Glyco-Oxidative Status and Lipo-Oxidation in Master Athletes. Nutrients 2016, 8, 745.

- Simioni, C.; Zauli, G.; Martelli, A.M.; Vitale, M.; Sacchetti, G.; Gonelli, A.; Neri, L.M. Oxidative stress: Role of physical exercise and antioxidant nutraceuticals in adulthood and aging. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 17181–17198.

- Cavaliere, G.; Trinchese, G.; Penna, E.; Cimmino, F.; Pirozzi, C.; Lama, A.; Annunziata, C.; Catapano, A.; Mattace Raso, G.; Meli, R.; et al. High-Fat Diet Induces Neuroinflammation and Mitochondrial Impairment in Mice Cerebral Cortex and Synaptic Fraction. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 509.

- Zia, A.; Farkhondeh, T.; Pourbagher-Shahri, A.M.; Samarghandian, S. The role of curcumin in aging and senescence: Molecular mechanisms. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 134, 111119.

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.G.; Shin, D.M. Advances of Cancer Therapy by Nanotechnology. Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 41, 1–11.

- Panaro, M.A.; Benameur, T.; Porro, C. Extracellular Vesicles miRNA Cargo for Microglia Polarization in Traumatic Brain Injury. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 901.

- Pricci, M.; Bourget, J.-M.; Robitaille, H.; Porro, C.; Soleti, R.; Mostefai, H.A.; Auger, F.A.; Martinez, M.C.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Germain, L. Applications of Human Tissue-Engineered Blood Vessel Models to Study the Effects of Shed Membrane Microparticles from T-Lymphocytes on Vascular Function. Tissue Eng. Part A 2009, 15, 137–145.

- Biancatelli, R.M.C.; Solopov, P.A.; Catravas, J.D. The Inflammasome NLR Family Pyrin Domain-Containing Protein 3 (NLRP3) as a Novel Therapeutic Target for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2022, 192, 837–846.

- Huang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhou, R. NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 2114–2127.

- Bauernfeind, F.G.; Horvath, G.; Stutz, A.; Alnemri, E.S.; Macdonald, K.L.; Speert, D.P.; Fernandes-Alnemri, T.; Wu, J.; Monks, B.G.; Fitzgerald, K.; et al. Cutting Edge: NF-κB Activating Pattern Recognition and Cytokine Receptors License NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Regulating NLRP3 Expression. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 787–791.

- Masters, S.L.; Dunne, A.; Subramanian, S.L.; Hull, R.L.; Tannahill, G.M.; Sharp, F.A.; Becker, C.; Franchi, L.; Yoshihara, E.; Chen, Z.; et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by islet amyloid polypeptide provides a mechanism for enhanced IL-1β in type 2 diabetes. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 897–904.

- Man, S.M.; Kanneganti, T.-D. Regulation of inflammasome activation. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 265, 6–21.

- Franchi, L.; Muñoz-Planillo, R.; Núñez, G. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 325–332.

- Lamkanfi, M.; Dixit, V.M. Mechanisms and Functions of Inflammasomes. Cell 2014, 157, 1013–1022.

- Zhang, W.-J.; Chen, S.-J.; Zhou, S.-C.; Wu, S.-Z.; Wang, H. Inflammasomes and Fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 643149.

- Wang, B.; Yin, Q. AIM2 inflammasome activation and regulation: A structural perspective. J. Struct. Biol. 2017, 200, 279–282.

- Doly J, Civas A, Navarro S, Uze G. Type I interferons: Expression and signalization. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 1998, 54, 1109–1121.

- Dinarello, C.A. Immunological and Inflammatory Functions of the Interleukin-1 Family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 27, 519–550.

- Lamkanfi, M. Emerging inflammasome effector mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 213–220.

- Lorenz, G.; Darisipudi, M.N.; Anders, H.-J. Canonical and non-canonical effects of the NLRP3 inflammasome in kidney inflammation and fibrosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 29, 41–48.

- He, Y.; Hara, H.; Núñez, G. Mechanism and Regulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 1012–1021.

- Li, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Xin, Q.-L.; Guan, Z.-Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.-A.; Li, X.-K.; Xiao, G.-F.; Lozach, P.-Y.; et al. SFTSV Infection Induces BAK/BAX-Dependent Mitochondrial DNA Release to Trigger NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 4370–4385.e7.

- Paik, S.; Kim, J.K.; Silwal, P.; Sasakawa, C.; Jo, E.-K. An update on the regulatory mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 1141–1160.

- Duncan, J.A.; Canna, S.W. The NLRC4 Inflammasome. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 281, 115–123.

- Schnappauf, O.; Chae, J.J.; Kastner, D.L.; Aksentijevich, I. The Pyrin Inflammasome in Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1745.

- Heilig, R.; Broz, P. Function and mechanism of the pyrin inflammasome. Eur. J. Immunol. 2017, 48, 230–238.