Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Akira Kawaguchi.

Grapevine crown gall (GCG), which is caused by tumorigenic

Allorhizobium vitis

(=

Rhizobium vitis

), is the most important bacterial disease in grapevine, and its economic impact on grapevine is very high. When young vines develop GCG, they often die, whereas older vines may show stress and poor growth depending on the severity of GCG, because GCG interferes with the vascular system of the grapevine trunk and prevents nutrient flow, leading to inferior growth and death. Viticultural practices and chemical control designed to inhibit GCG are only partially effective presently; thus, a biocontrol procedure could be a desirable and effective approach for GCG prevention.

- Allorhizobium vitis

- grapevine crown gall

- biocontrol

1. Introduction

1.1. What Is Crown Gall?

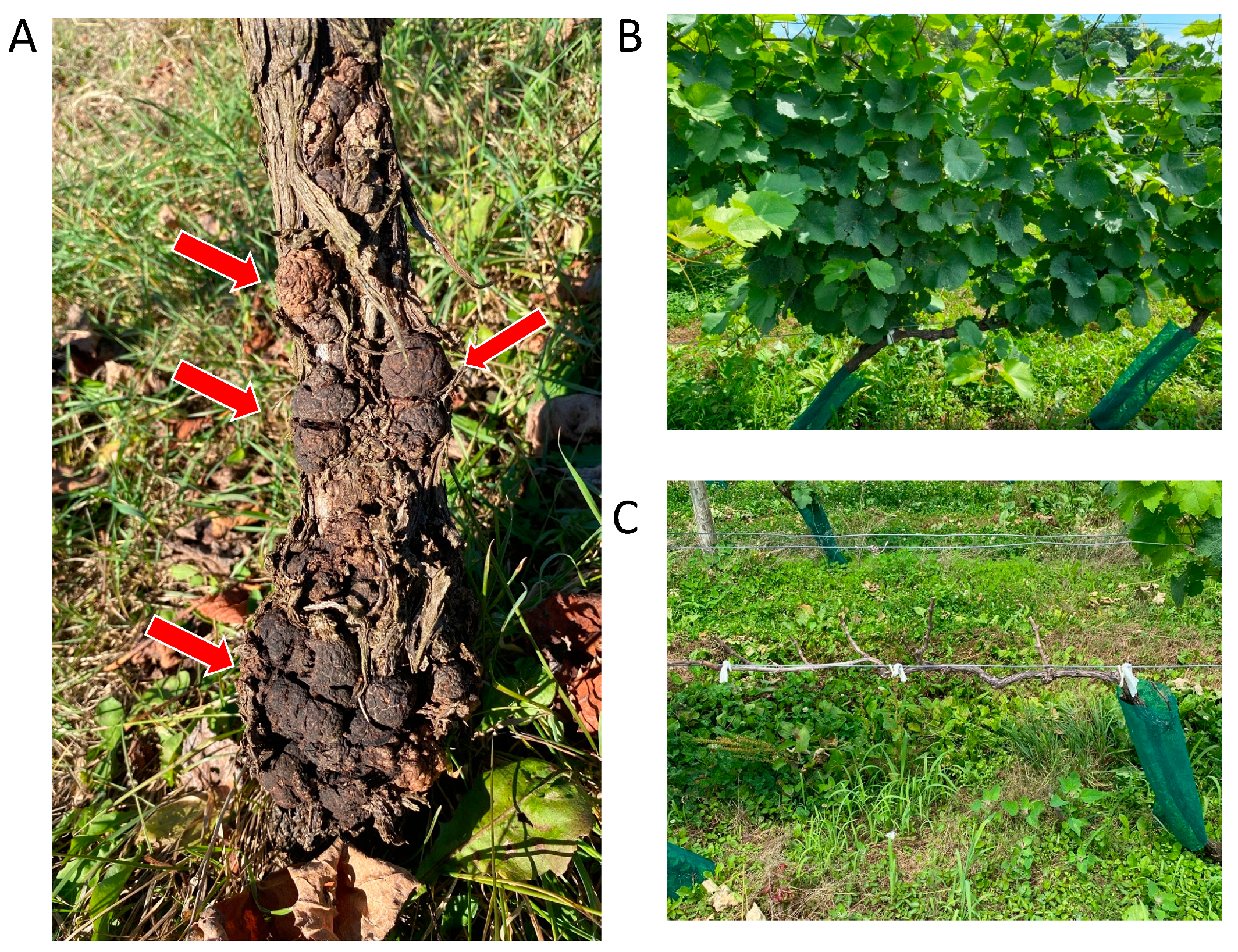

Crown gall (CG) is one of the most important soil-borne diseases [1,2,3,4][1][2][3][4]. Symptoms of CG are identified as overgrowths appearing as the formation of “galls” (tumors) on roots and/or at the base of plants [1,2,3,4,5][1][2][3][4][5]. In addition, grapevine crown gall (GCG) is one of the most important and economically destructive diseases in viticulture around the world [2,3,4,5][2][3][4][5]. GCG is mainly caused by plant pathogenic bacteria Allorhizobium vitis (Ti) (=Rhizobium vitis (Ti), Agrobacterium vitis (Ti), and A. tumefaciens biovar 3), where “Ti” indicates “tumorigenic” [6]. Countries with GCG include China, Japan, Chile, South Africa, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Spain, and many countries in Europe, North and South America, and the Middle East [3,4][3][4]. CGs usually form on the trunks and cordons of old and young grapevines, including even 1-year-old nursery stocks (Figure 1A) [4]. Infected grapevines often grow poorly, and GCG causes partial or complete grapevine death [7] (Figure 1B,C). In plants with gall symptoms, the risks of inferior growth and death become 14.8-fold and 18.0-fold greater than in plants with no gall symptoms, respectively, indicating that poor growth and death are highly increased by GCG incidence [7]. In addition, in grapevines, wounding events (e.g., mechanical damages or freezing injuries) are often associated with the occurrence of GCG, because wounded plant tissues are susceptible to infection by A. vitis [2,3,4][2][3][4].

Figure 1. Grapevine crown gall (GCG): (A) Galls formed on grapevine stems. Red arrows indicate galls. (B) Healthy grapevine without GCG. (C) Complete grapevine death by GCG.

1.2. Mechanism of GCG Development

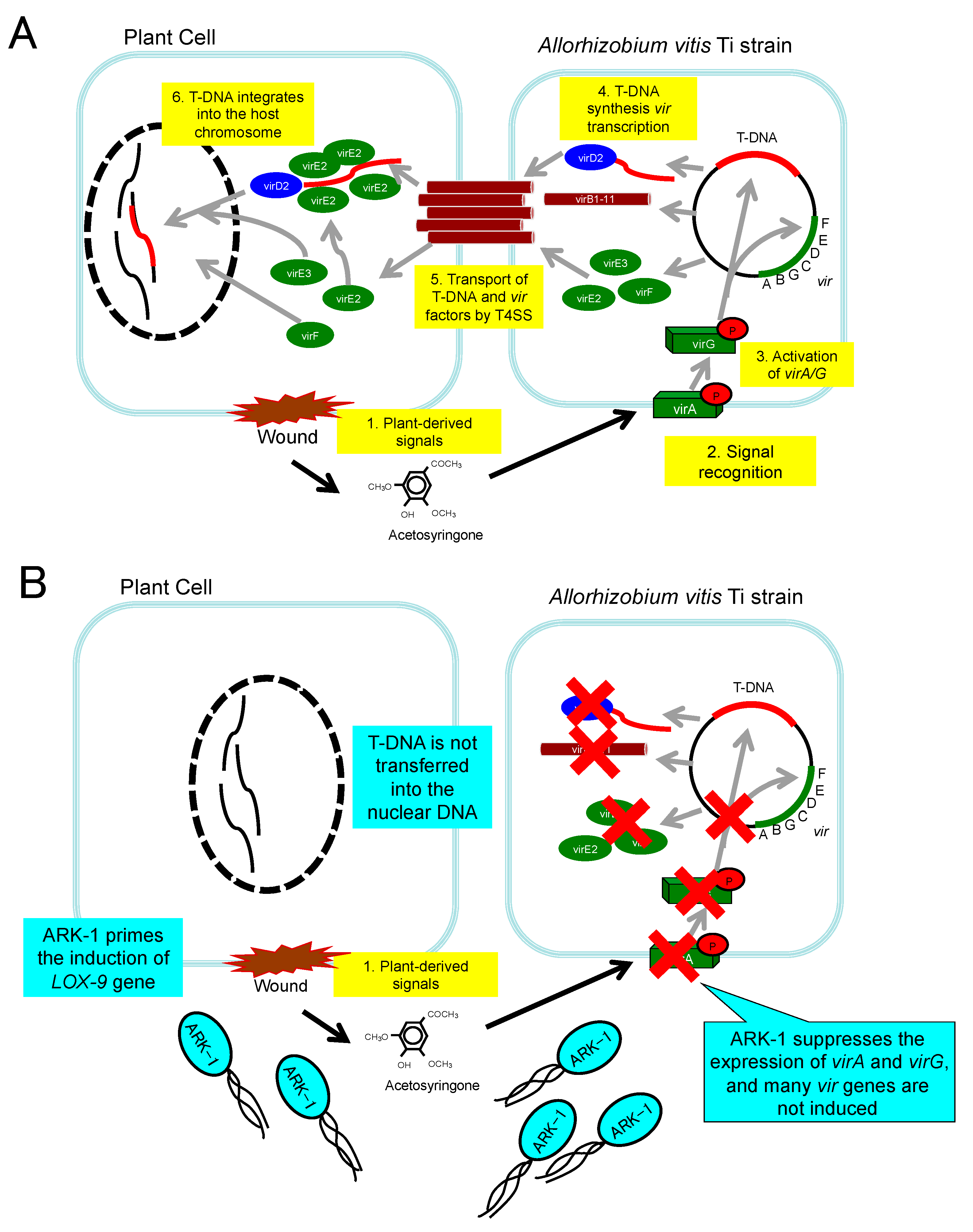

Abnormal cell development is due to the transfer of DNA from Ti strains as the CG pathogen into the plant [8,9,10,11][8][9][10][11]. The bacterial DNA is transferred, incorporated into, and expressed in the plant genomic DNA (Figure 2A) [8,9,10,11][8][9][10][11]. The infection of plants by A. vitis (Ti) is a multistage process [8,9,10,11][8][9][10][11]. The first step is the chemotactic attraction to plant cells wounded due to a variety of causes, such as grafting and/or some mechanical damages (Figure 2A) [2,3,4,5][2][3][4][5]. A. vitis moves to the underground portion of the grapevine and attaches itself to cells (Figure 2A). Transfer DNA (T-DNA) and virulence (vir)-related genes are located mostly on tumor-inducing plasmids (pTi). A. vitis (Ti) strains transfer T-DNA in the single-strand form and several virulence effector proteins into plant host cells through a bacterial type IV secretion system [8,9,10,11][8][9][10][11]. The plant molecule acetosyringone (AS) induces the whole vir regulon in A. vitis (Ti) (Figure 2A) [7,8,9,10][7][8][9][10]. In nature, AS specifically occurs in the exudates from injured and metabolically active plant cells and allows Ti strains to identify susceptible plant cells [8,9,10,11][8][9][10][11]. The transfer of T-DNA and processing need products of the vir genes (virA-E, and G) (Figure 2A) [8,9,10,11][8][9][10][11]. T-DNA is transferred and injected into the plant nuclear DNA (Figure 2A) [8,9,10,11][8][9][10][11]. The posterior expression of T-DNA results in the overproduction of cytokinins and auxins [8,9,10,11][8][9][10][11]. Eventually, an abnormal gall forms in the host plant (Figure 2A) [8,9,10,11][8][9][10][11]. Then, T-DNA genes in gall tissues produce gall-specific compounds called opines, which serve as nutrients for A. vitis [3].

Figure 2. Mechanism of grapevine crown gall (GCG) in a plant cell: (A) The infection of plants by tumorigenic Allorhizobium vitis strain is a multistage process. Tumorigenic A. vitis strains transfer T-DNA and effector proteins. (B) The hypothesis of ARK-1′s effect mechanism: ARK-1 suppresses the expression of virA and virG and then inhibits the pathway of T-DNA transfer into the nuclear DNA of the plant. The ISR priming phenomenon induced by ARK-1 might be a related to its mechanism as a subordinate factor.

1.3. Necessity of GCG Management

The most serious problem is the lack of effective control methods against GCG. Viticultural practices and chemical control designed to inhibit GCG are only partially effective presently. Although copper bactericides and antibiotics are able to kill the bacterium upon contact, they do not penetrate the plants and come into contact with the Ti strains residing inside systemically. Thus, a biocontrol procedure could be a desirable and effective approach to GCG management [3]. The history of the search for practical biocontrol agents for CG goes back to the early 1970s [12,13,14][12][13][14]. R. rhizogenes (=A. rhizogenes and A. radiobacter biovar 2) strain K84 prevents the growth of Rhizobium strains and decreases CG formation [12,13,14,15,16][12][13][14][15][16]. K84 produces an antibacterial molecule, agrocin 84, that is antagonistic to certain Ti strains of Agrobacterium and Rhizobium [12,13,14,15,16,17][12][13][14][15][16][17]. Strain K84 has been used successfully to prevent CG incidence in various plant species [12,13,14,15,16,17][12][13][14][15][16][17]. A new biocontrol strain, K1026, has been constructed using recombinant DNA techniques [18]. K1026 is unable to transfer its mutant agrocin 84 plasmid, designated pAgK1026, to other agrobacteria [18,19][18][19]. However, K84 does not inhibit GCG caused by tumorigenic A. vitis [2,3,4][2][3][4].

Several laboratories have attempted to identify other biocontrol agents for GCG (Table 1) [2,4,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46][2][4][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46]. Staphorst et al. [20] evaluated nonpathogenic A. vitis strain F2/5, which suppressed the growth of A. vitis (Ti) strains in culture plates and inhibited GCG in wounded stems in greenhouse experiments. F2/5 was reported to produce a bacteriocin that inhibits CG at the wound sites on plant stems inoculated with an A. vitis (Ti) strain and to have a mechanism associated with quorum sensing (QS) and polyketide synthesis based on caseinolytic protease component (clp) genes [21,22,23,24][21][22][23][24]. However, F2/5 was shown to have very low antibiotic activity against tumorigenic A. radiobacter (=R. radiobacter (Ti), A. tumefaciens (Ti), and A. tumefaciens biovar 1) and R. rhizogenes (=A. rhizogenes (Ti) and A. tumefaciens biovar 2) and not to inhibit CG caused by other Ti strains of A. vitis [22,23,24][22][23][24]. Chen and Xiang [26] reported that A. radiobacter strain HLB-2 isolated from CGs from hop produced an agrocin-like compound and inhibited A. vitis (Ti) strains in medium plates.

Table 1. Bacterial strains that have been evaluated for biocontrol of grapevine crown gall (GCG).

| Bacterium | Strain | Origin | Reference | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allorhizobium vitis | (nonpathogenic) | VAR03-1 | Grapevine, Japan | [2,4,33, | [33] | 34, | [34] | 36, | [36] | 37, | [37] | 42,43,44] | [2][4][42][43][44] |

| Allorhizobium vitis | (nonpathogenic) | ARK-1 | Grapevine, Japan | [4,35,40,41,45,46] | [4][35][40][41][45][46] | ||||||||

| Allorhizobium vitis | (nonpathogenic) | ARK-2 | Grapevine, Japan | [4,35] | [4][35] | ||||||||

| Allorhizobium vitis | (nonpathogenic) | ARK-3 | Grapevine, Japan | [4,35] | [4][35] | ||||||||

| Allorhizobium vitis | (nonpathogenic) | F2/5 | Grapevine, South Africa | [20,21,22,23,24] | [20][21][22][23][24] | ||||||||

| Rhizobium rhizogenes | (tumorigenic) | J73 | Plum, South Africa | [25] | |||||||||

| Allorhizobium vitis | (nonpathogenic) | E26 | Grapevine, China | [27,28] | [27][28] | ||||||||

| Agrobacterium radiobacter | (nonpathogenic) | HLB-2 | Hop, China | [26] | |||||||||

| Rahnella aquatilis | HX2 | Grapevine, China | [29] | ||||||||||

| Agrobacterium radiobacter | (nonpathogenic) | MI15 | Grapevine, China | [30] |

As described above, several researchers have tried to develop other biocontrol agents for GCG and reported potential bacterial and fungal strains, but no practical development has been achieved to date due to the lack of successful evidence from field trials. This revisewarch focuses on nonpathogenic A. vitis strain ARK-1 as a new antagonistic strain, which was identified to strongly inhibit GCG in vineyards and has a unique biocontrol mechanism (Figure 2B and Figure 3).

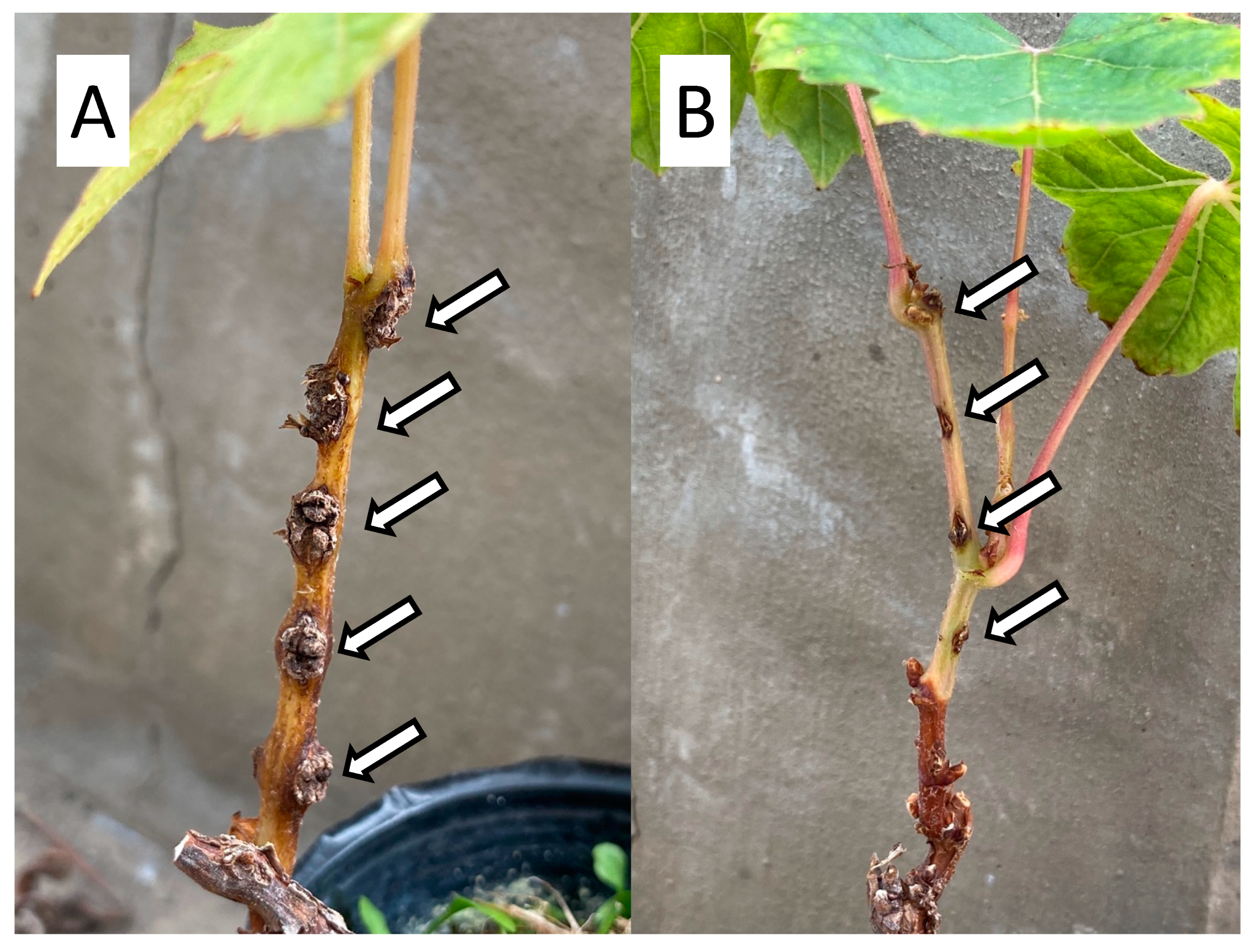

Figure 3. Effect of nonpathogenic A. vitis (Ti) strain ARK-1 on gall formation: (A) A stem of grapevine seedlings was inoculated with the A. vitis (Ti) strain alone. White arrows indicate galls forming at the inoculated site. (B) A stem of grapevine was inoculated with mixtures of Ti and ARK-1 strains in a 1:1 cell ratio at the same time. White arrows indicate no gall formation at the inoculation wound site.

2. Screening Tests for Biocontrol Agents

A field survey of potential A. vitis (Ti) infections of grapevine in Okayama Prefecture, Japan, isolated numerous nonpathogenic A. vitis strains [32,33][32][33]. Screening tests for nonpathogenic A. vitis strains as biocontrol agents using the needle-prick method were carried out [33,34,35][33][34][35] on over 500 candidate strains to evaluate their activities against a Ti strain. In a test employing a 1:1 cell ratio of Ti and nonpathogenic strains applied to the stems of seedings of grapevine, sunflower, and tomato, some strains strongly inhibited gall formation and its size compared with plants inoculated with a Ti strain alone (Figure 3). Then, nonpathogenic A. vitis strains VAR03-1, ARK-1, ARK-2, and ARK-3 were chosen as biocontrol agents [33,34,35][33][34][35]. In seedlings of grapevine, each strain (VAR03-1 and ARK-1 to -3) added to the mixture (1:1 cell ratio) of seven different A. vitis (Ti) strains, which had been isolated in three different countries (Australia, Greece, and Japan) significantly inhibited gall development in grapevine stems [33,34,35,36,37,38][33][34][35][36][37][38]. The ARK-1 strain was the strongest among the tested strains, and ARK-1 reduced gall development by 90.6% compared with grapevine seedlings inoculated with the Ti strain alone (Figure 3) [34]. Moreover, ARK-1 co-inoculation significantly reduced gall formation and gall size caused by A. vitis Ti strains isolated in several vineyards in Virginia, which is in the mid-Atlantic region of the USA [39]. These results suggest that the ARK-1 strain could be a promising new agent to control GCG in several grape-growing regions in the world.

3. Root-Dipping Inoculation for Practical Use

3.1. Field Trials

Field trials are an essential part of the development of new agricultural technologies and are especially important for developing biocontrol agents. Even if positive results may be obtained in laboratory and/or greenhouse experiments, field experiments often show unexpected results. Therefore, field trials were conducted to confirm the control effect of strains ARK-1 and VAR03-1 using the root-dipping method with 1- or 2-year-old grapevine nursery stocks in some experimental and commercial fields [4,34,35,41,42,43][4][34][35][41][42][43]. From 2009 to 2019, nine field trials for the biocontrol of GCG were carried out in three different fields [4,42][4][42]. The roots of plants (nursery stocks of grapevine) were soaked for 1 h in ARK-1 cell suspension (107 to 108 cells/mL) or water, and they were planted in Ti-contaminated vineyards [4,44][4][44]. The results in several field trials were subjected to a meta-analysis, which is one of the statistical techniques for combining findings from independent experiments [4,44,45][4][44][45]. The effect size of antagonist treatment was demonstrated as an integrated risk ratio (IRR) [4,44,45][4][44][45].

The IRR was 0.18 (95% confidence interval, 0.10–0.32), indicating that ARK-1 treatment significantly reduced the GCG incidence regardless of the differences in grape cultivars, fields, and year [4,44][4][44]. The IRR value of 0.18 suggested that GCG incidence during ARK-1 treatment was reduced to 18% of that without ARK-1, indicating that the control effect was extremely high in the vineyards. In addition to grapevine, ARK-1 was reported to be able to effectively control CG in rose, tomato, Japanese pear, peach, and apple trees caused by A. radiobacter (Ti) (=R. radiobacter (Ti)) and R. rhizogenes (Ti) strains in greenhouse and field trials [45]. Therefore, ARK-1 effectively protects six different species of host plants, including grapevine, against three different genera and species of Agrobacterium, Rhizobium, and Allorhizobium Ti strains, and this represents the first achievement in the biocontrol of CG in various plant species [4,44,45][4][44][45].

3.2. Population Dynamics of ARK-1 in Roots of Grapevine

When plant diseases are controlled using biocontrol, antagonistic microorganisms need to colonize the host plants well during cultivation. It was reported that the ARK-1 strain was inoculated into roots using the root-dipping method, and ARK-1 was isolated from the roots [4,44][4][44]. The result suggested that ARK-1 established populations in the rhizosphere and persisted inside the roots for up to 36 months [4,44][4][44]. Although the microbial diversity in grapevine is rich [46], ARK-1 can survive inside grapevine for at least 36 months [4,44][4][44]. Thus, ARK-1 is one of the endophytic bacteria. The ability of ARK-1, which is able to colonize grapevine roots, could stably affect the persistence of GCG control.

References

- Kado, C.I. Crown gall. The Plant Health Instructor 2002.

- Kawaguchi, A. Biological control for grapevine crown gall. In Grapevines: Varieties, Cultivation and Management; Szabo, P.V., Shojania, J., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 153–167.

- Burr, T.J.; Bazzi, C.; Süle, S.; Otten, L. Crown gall of grape: Biology of Agrobacterium vitis and the development of disease control strategies. Plant Dis. 1998, 82, 1288–1297.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Inoue, K.; Tanina, K.; Nita, M. Biological control for grapevine crown gall using nonpathogenic Rhizobium vitis strain ARK-1. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2017, 93, 547–560.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Inoue, K. Grapevine crown gall caused by Rhizobium radiobacter (Ti) in Japan. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2009, 75, 205–212.

- Mousavi, S.A.; Willems, A.; Nesme, X.; de Lajudie, P.; Lindstrom, K. Revised phylogeny of Rhizobiaceae: Proposal of the delineation of Pararhizobium gen. nov., and 13 new species combinations. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 38, 84–90.

- Kawaguchi, A. Risk assessment of inferior growth and death of grapevines due to crown gall. Euro. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 162. in press.

- Chilton, M.D.; Drummond, M.H.; Merlo, D.J.; Sciaky, D.; Montoya, A.L.; Gordon, M.P.; Nester, E.W. Stable incorporation of plasmid DNA into higher plant cells: The moleculer basis of crown gall tumorigenesis. Cell 1977, 11, 263–271.

- Zupan, J.R.; Zambryski, P. The Agrobacterium DNA transfer complex. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 1997, 16, 279–295.

- Gelvin, S.B. Traversing the cell: Agrobacterium T-DNA’s journey to the host genome. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 52.

- Nester, E.W. Agrobacterium: Nature’s genetic engineer. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 730.

- New, P.B.; Kerr, A. Biological control of grown gall: Field measurements and glasshouse experiments. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1972, 35, 279–287.

- Kerr, A.; Htay, K. Biological control of crown gall through bacteriocin production. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 1974, 4, 37–44.

- Moore, L.W.; Warren, G. Agrobacterium radiobacter strain 84 and biological control of crown gall. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 1979, 17, 163–179.

- Kerr, A. Biological control of crown gall through production of agrocin 84. Plant Dis. 1980, 64, 24–30.

- Kerr, A.; Bullard, G. Biocontrol of crown gall by Rhizobium rhizogenes: Challenges in biopesticide commercialization. Agronomy 2020, 20, 1126.

- Reader, J.S.; Ordoukhanian, P.T.; Kim, J.G.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Hwang, I.; Farrand, S.; Schimmel, P. Major biocontrol of plant tumors targets tRNA synthetase. Science 2005, 309, 1533.

- Jones, D.A.; Kerr, A. Agrobacterium radiobacter strain K1026, a genetically engineered derivative of strain K84, for biological control of crown gall. Plant Dis. 1989, 73, 15–18.

- Penyalver, R.; Vicedo, B.; López, M.M. Use of the genetically engineered Agrobacterium strain K1026 for biological control of crown gall. Euro. J. Plant Pathol. 2000, 106, 801–810.

- Staphorst, J.L.; van Zyl, F.G.H.; Strijdom, B.W.; Groenewold, Z.E. Agrocin-producing pathogenic and nonpathogenic biotype-3 strains of Agrobacterium tumefaciens active against biotype-3 pathogens. Curr. Microbiol. 1985, 12, 45–52.

- Burr, T.J.; Reid, C.L. Biological control of grape crown gall with nontumorigenic Agrobacterium vitis F2 ⁄ 5. Am. J. Enol. Viticul. 1994, 45, 213–219.

- Burr, T.J.; Reid, C.L.; Taglicti, E.; Bazzi, C.; Süle, S. Biological control of grape crown gall by strain F2/5 is not associated with agrocin production or competition for attachment site on grape cells. Phytopathology 1997, 87, 706–711.

- Burr, T.J.; Otten, L. Crown gall of grape: Biology and disease management. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1999, 37, 53–80.

- Kaewnum, S.; Zheng, D.; Reid, C.L.; Johnson, K.L.; Gee, J.C.; Burr, T.J. A host-specific biological control of grape crown gall by Agrobacterium vitis strain F2/5; its regulation and population dynamics. Phytopathology 2013, 103, 427–435.

- Webster, J.; Thomson, J.A. Agrocin-producing Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain active against grapevine isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1986, 52, 217–219.

- Chen, X.Y.; Xiang, W.N. A strain of Agrobacterium radiobacter inhibits growth and gall formation by biotype III strains of Agrobacterium tumefaciens from grapevine. Acta. Microbiol. Sin. 1986, 26, 193–199.

- Wang, H.M.; Wang, H.X.; Ng, T.B.; Li, J.Y. Purification and characterization of an antibacterial compound produced by Agrobacterium vitis strain E26 with activity against A. tumefaciens. Plant Pathol. 2003, 52, 134–139.

- Liang, Y.; Di, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ma, D. A biotype 3 strain of Agrobacterium radiobacter inhibits crown gall formation on grapevine. Acta Microbiol. Sin. 1990, 30, 165–171.

- Chen, F.; Guo, Y.B.; Wang, J.H.; Li, J.Y.; Wang, H.M. Biological control of grape crown gall by Rahnella aquatilis HX2. Plant Dis. 2007, 91, 957–963.

- Xie, X.M.; You, J.F.; Chen, P.M.; Guo, J.M. On a strain MI15 of Agrobacterium radiobacter for biological control of grapevine crown gall. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 1993, 23, 137–141.

- Ferrigo, D.; Causin, R.; Raiola, A. Effect of potential biocontrol agents selected among grapevine endophytes on crown gall disease. Bio Control. 2017, 62, 821–833.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Sawada, H.; Inoue, K.; Nasu, H. Multiplex PCR for the identification of Agrobacterium biover 3 strains. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2005, 71, 54–59.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Inoue, K.; Nasu, H. Inhibition of crown gall formation by Agrobacterium radiobacter biovar 3 strains isolated from grapevine. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2005, 71, 422–430.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Inoue, K. New antagonistic strains of non-pathogenic Agrobacterium vitis to control grapevine crown gall. J. Phytopathol. 2012, 160, 509–518.

- Kawaguchi, A. Studies on the diagnosis and biological control of grapevine crown gall and phylogenetic analysis of tumorigenic Rhizobium vitis. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2009, 75, 462–463.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Sawada, H.; Ichinose, Y. Phylogenetic and serological analyses reveal genetic diversity of Agrobacterium vitis strains in Japan. Plant Pathol. 2008, 57, 747–753.

- Kawaguchi, A. Genetic diversity of Rhizobium vitis strains in Japan based on multilocus sequence analysis of pyrG, recA and rpoD. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2011, 77, 299–303.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Sone, T.; Ochi, S.; Matsushita, Y.; Noutoshi, Y.; Nita, M. Origin of pathogens of grapevine crown gall disease in Hokkaido in Japan as characterized by molecular epidemiology of Allorhizobium vitis strains. Life 2021, 11, 1265.

- Wong, A.T.; Kawaguchi, A.; Nita, M. Efficacy of a biological control agent Rhizobium vitis ARK-1 against Virginia R. vitis isolates, and relative relationship among Japanese and Virginia R. vitis isolates. Crop Prot. 2021, 146, 105685.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Noutoshi, Y. Migration of biological control agent Rhizobium vitis strain ARK-1 in grapevine stems and inhibition of galls caused by tumorigenic strain of R. vitis. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2022, 88, 63–68.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Inoue, K.; Nasu, H. Biological control of grapevine crown gall by nonpathogenic Agrobacterium vitis strain VAR03-1. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2007, 73, 133–138.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Inoue, K.; Ichinose, Y. Biological control of crown gall of grapevine, rose, and tomato by nonpathogenic Agrobacterium vitis strain VAR03-1. Phytopathology 2008, 98, 1218–1225.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Kondo, K.; Inoue, K. Biological control of apple crown gall by nonpathogenic Rhizobium vitis strain VAR03-1. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2012, 78, 287–293.

- Kawaguchi, A. Biological control of crown gall on grapevine and root colonization by nonpathogenic Rhizobium vitis strain ARK-1. Microbes Environ. 2013, 28, 306–311.

- Kawaguchi, A.; Inoue, K.; Tanina, K. Evaluation of the nonpathogenic Agrobacterium vitis strain ARK-1 for crown gall control in diverse plant species. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 409–414.

- Gan, H.M.; Szegedi, E.; Fersi, R.; Chebil, S.; Kovács, L.; Kawaguchi, A.; Hudson, A.O.; Burr, T.J.; Michael, A.; Savka, M.A. Insight into the microbial co-occurrence and diversity of 73 grapevine (Vitis vinifera) crown galls collected across the northern hemisphere. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1896.

More