Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 3 by Rita Xu.

Ganoderma has been used as a traditional medicine in Asian countries to prevent and treat various diseases. Numerous publications are stating that Ganoderma species have a variety of beneficial medicinal properties, and investigations on different metabolic regulations of Ganoderma species, extracts or isolated compounds have been performed both in vitro and in vivo.

- bioactivity

- bioactive molecules

- drug

- Ganoderma

- Triterpenoids

1. Introduction

Ganoderma P. Karst. 1881 [1] is an old polypore genus typified by Ganoderma lucidum (Curtis) P. Karst. belonging to the family Ganodermataceae (basidiomycete) [2], which has been synonymized with the family Polyporaceae [3], with the members normally growing on woody plants and logs [2][4][5]. The genus was originally reported in the UK [6] and is considered to have a worldwide distribution [7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]. Ganoderma species are used for medicinal purposes in China [19][20][21][22], Japan, South Korea [22] and the French West Indies [12]. The common names for Ganoderma include Lingzhi, Munnertake, Sachitake, Reishi, and Youngzhi. Ganoderma was first recorded in Shennong’s Classic of Materia Medica and classified as an upper-grade medicine in medical books [23]. Index Fungorum (2022) (http://www.indexfungorum.org/, accessed on 6 September 2022) lists 488 records of Ganoderma while MycoBank lists 529 records [18]. Approximately 80 species of Ganoderma are recorded in Chinese Fungi [24], of which G. lucidum and G. sinense are described as medicinally beneficial macrofungi in Chinese medicine [25]. However, other species, such as G. capense, G. cochlear and G. tsugae also play an important role in traditional folk medicine. In addition, pharmacological studies have also used the extract and chemical constituents of other Ganoderma species [22][26][27][28][29][30].

The chemical constituents and the biological activities of 25 species of Ganoderma, namely G. amboinense, G. annulare, G. applanatum (synonym G. lipsiense), G. australe, G. boninense, G. capense, G. carnosum, G. casuarinicola, G. cochlear, G. colossus, G. concinnum, G. ellipsoideum, G. fornicatum, G. hainanense, G. lucidum, G. mastoporum, G. neo-japonicum, G. orbiforme, G. pfeifferi, G. resinaceum, G. sinense, G. theaecola (as theaecolum), G. tropicum, G. tsugae and G. weberianum were studied and reported in this review. Several chemical constituents such as ganoderic acids, lucidenic acids, 12-hydroxyganoderic acid, ganorbiformin, lucidimines [31] and other compounds have been reported from various Ganoderma species during recent decades [29][32][33][34][35].

Triterpenes, polysaccharides and peptidoglycans are one of the major types of bioactive substances [36][37] responsible for the various biological activities of several species in Ganoderma (e.g., Ganoderma lucidum). Triterpenoids and ganoderic acids that play a critical role in pharmacological activities are also present in G. applanatum and G. orbiforme [33][36][38][39][40][41][42]. Besides G. applanatum [43][44], G. colossus [45] and G. pfeifferi [46], G. resinaceum [45] have also been identified as potential Ganoderma natural antioxidants.

G. amboinense [47], G. annulare [48], G. applanatum [49][50][51], G. boninense [52], G. calidophilum [53], G. capense [54], G. carnosum [55], G. cochlear [56][57][58], G. colossum [59], G. concinnum, G. neo-japonicum [60], G. fornicatum [61], G. hainanense [62], G. leucocontextum [63], G. lucidum [64][65][66][67], G. mastoporum [68], G. mbrekobenum [69], G. resinaceum [70], G. sinense [71][72][73], G. theaecola (as theaecolum) [74], G. tropicum [75], G. tsugae [76], G. weberianum [77] were reported to contain bioactive compounds of great interest.

The members of the genus Ganoderma are rich in novel “mycochemicals”, including polysaccharides [78], steroids, fatty acids, phenolic compounds, vitamins, amino acids and triterpenoids [69][79][80][81]. Ganoderma polysaccharides are a hot topic in the medicinal mushroom research field [78][82][83][84]. Although polysaccharides are found to be one of the main bioactive constituents, their high molecular weight and complex structure limit their use in the drug market [85]. The Ganoderma polysaccharides are well known for their diverse bioactivities such as antitumor, immunomodulatory, anti-hypertensive, antidyslipidemic and hepatoprotective activities. Ganoderma polysaccharides have been developed into medicines, dietary supplements, healthy foods, treat and prevent diseases, and are continuing to serve as important leads in modern drug discovery [78][86][87][88].

Taxonomic Studies of Ganoderma

The word Ganoderma is derived from the Greek words “Gano”, meaning “shiny”, and “derma”, meaning “skin” [22][89]. Originating from the tropics and recently extending its range into temperate zones [90], Ganoderma is an old genus with a taxonomic history dating back to 1881, and the Finnish mycologist P. A. Karsten erected the genus to place a single species, Polyporus lucidus [=Ganoderma lucidum (Curtis: Fr.) P. Karst.] [1][91]. Ganoderma lucidum is the type species of the genus Ganoderma, which was originally described as from the UK and later found to have a worldwide distribution [6]. A number of Ganoderma species morphologically closely related and belonging to G. lucidum complex viz. G. multipileum Ding Hou 1950 [92], G. sichuanense J.D. Zhao & X.Q. Zhang 1983 [93] and G. lingzhi Sheng H. [94][95] from China, G. resinaceum Boud. 1889 [96] from Europe, and G. oregonense Murrill 1908, G. sessile Murrill 1902, G. tsugae Murrill 1902 and G. zonatum Murrill 1902 [97][98] from the USA, have been described as from all over the world, and are mainly characterized by laccate pileus. Zhou et al. [99] considered 32 collections belonging to the G. lucidum complex from Asia, Europe and North America in terms of their morphology and phylogeny as derived from analyses of four protein-coding genes viz. Internal transcribed spacer (ITS), translational elongation factor 1-α (tef1-α) and retinol-binding protein 1 and 2 (rpb1, rpb2). Different molecular techniques have been used to study the genetic diversity in Ganoderma, such as amplified fragment length polymorphism, isozyme analysis, inter simple sequence repeat, random amplified polymorphic DNA, single-nucleotide polymorphism, restricted fragment length polymorphisms, sequence-related amplified polymorphism, single-strand conformational polymorphism and sequence characterized amplified region [100]. These different molecular identifications used in different taxonomic classifications of Ganoderma have caused great improvements and provide information for the further research of Ganoderma [18][90][101]. Ganoderma has long been treated as one of the most important medicinal fungi worldwide [39], and laccate species of Ganoderma have been considered for centuries [102], i.e., G. lucidum complex have been used as medicinal mushrooms in traditional Chinese medicine [103]. Anyhow, the species concept of the G. lucidum complex lacks agreement in morphology, and the taxonomy of this species complex is thus problematic, and this ultimately limits both further research on this complex and their medicinal usefulness. For example, the widely used medicinal species in biochemical and pharmaceutical studies have been assumed to be G. lucidum, but evidence has emerged that this medicinal species is, in fact, a different species [104] and was described as G. lingzhi [94]. The taxonomic position of the G. lucidum complex has long been subjected to debate [9][18][90][101][105] and different opinions have been expressed regarding the members and their validity in the complex. Haddow [106] treated G. sessile as a synonym of G. resinaceum, while Overholts [107] pointed out that G. lucidum should be the correct name of the specimens classified as G. sessile. Ganoderma lucidum has also been considered as the correct name over its later synonym G. tsugae [106][108]. However, with the support of mating tests, Nobles [109] pointed out that the specimens classified as G. lucidum in the USA represented G. sessile. All names of the G. lucidum complex in East Africa were parsimoniously treated as the ‘‘G. lucidum group’’, because of the lack of morpho-taxonomic solution to the problem in this complex [7]. Asian specimens classified as G. lucidum were divided into two clades; both were separated from European G. lucidum [110], with one clade being composed of tropical collections represented by G. multipileum, while the other clade was unknown [110], yet later recognized as G. sichuanense [111]. It was found that the holotype of G. sichuanense was not conspecific with the unknown clade, and the unknown clade was identified as a new species, G. lingzhi, which also is the most widely cultivated species in China [94]. Meanwhile, the distribution of genuine G. lucidum in China was also confirmed [94][112]. The taxonomy of the G. lucidum complex remains problematic even after several decades of debates [99]. Most of the studies previously conducted were focused on the species in a continent or specific region [94][111], or the phylogeny was described with low resolution to certain clades [104][112]. On the other hand, a strong phylogeny together with species originally described as from the USA is greatly needed, as most of these species are old and never referred to in any phylogenetic analyses.2. Triterpenoids

2.1. Biosynthesis of Triterpenoids

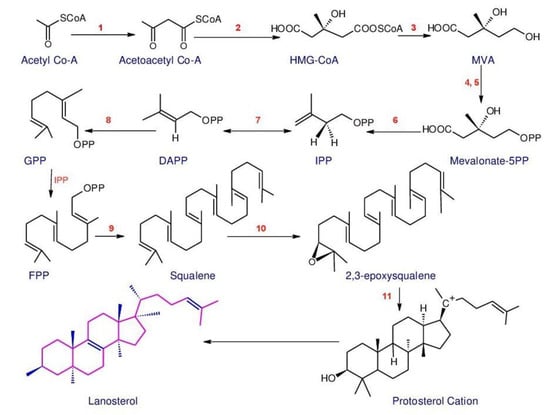

Triterpenoids belong to a large and structurally diverse class of natural products [113]. Basidiomycetes are considered a main source for triterpenoids. Compared to plants, very few types of triterpenoid skeletons have been reported in basidiomycetes, thus more research is needed [114]. Triterpenoids extracted from Ganoderma spp. are named as Ganoderma triterpenoids (GTs) [113]. Ganoderma triterpenoids (GTs) isolated from the fruiting bodies, cultured mycelia and basidiospores of Ganoderma [115][116][117] belong to the lanostane-type triterpenoids and are one of the major chemical constituents in Ganoderma. Studies have confirmed that GTs are biosynthesized using isoprenoid pathways [118][119]. This pathway was considered to start from acetyl-coenzyme A and termed as a Mevalonate pathway (MVA) [120]. The MVA pathway (Figure 1) is one of the important metabolic pathways that can be divided into four main processes: conversion, construction, condensation, and postmodification [35]. The initial step is the transformation of acetyl-coenzyme A to isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP). Then the activities of different prenyltransferases produce farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP), which are higher-order terpenoid building blocks from this IPP precursor. Then, these junction mediators can self-condense, and are also used in alkylation processes to produce prenyl side chains (for a range of nonterpenoids) or create a ring (to build the basic skeletons of triterpenoids). Ultimately, oxidation and reduction reactions, conjugation, isomerization or other secondary reactions magnify the distinctive characteristics of the triterpenoids [35][121][122].

Figure 1. Outline of the MVA and lanostane-type triterpenoids biosynthesis. Enzymes involved in the pathway are: 1. Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, AACT; 2. 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase, HMGS; 3. 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, HMGR; 4. Mevalonate kinase, MK; 5. Phosphomevalonate kinase, MPK; 6. Phosphomevalonate decarboxylase, MVD; 7. Isopentenyldiphosphate isomerase, IDI; 8. Farnesyl diphosphate synthase, FPPs; 9. Squalene synthase, SQS; 10. Squalene monooxygenase, SE; 11. 2,3-Oxidosqualene-lanosterol cyclase, OSC (The structures were redrawn in ACD/ChemSketch: Freeware: 2012).

2.2. Structures and Bioactivities of Triterpenoids

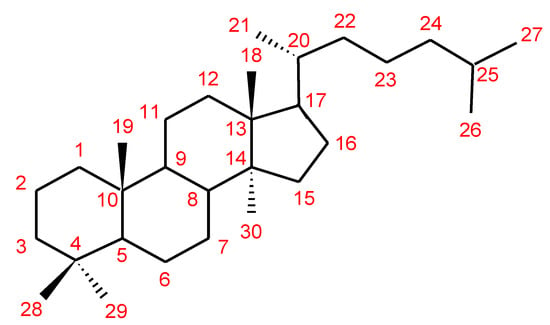

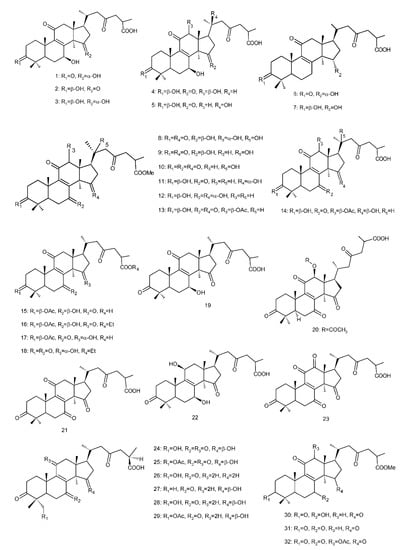

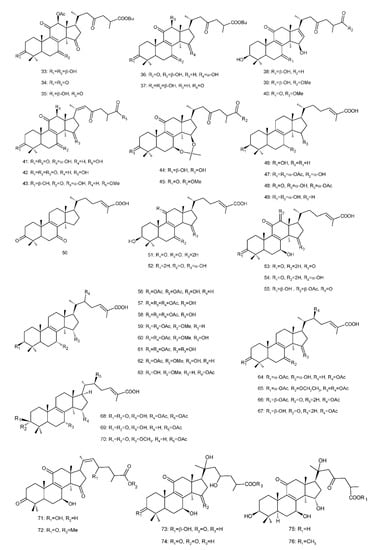

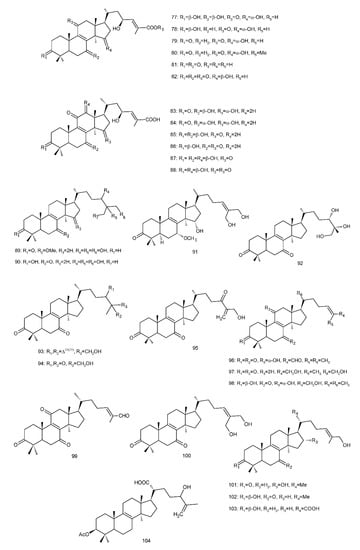

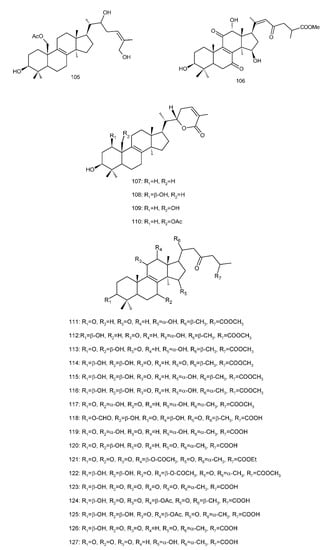

Triterpenes are a major class of widely dispersed secondary metabolites in nature [132]. Triterpenoids structures with a carbon skeleton are considered to be derived from the acyclic precursor squalene [133]. More than 30,000 structures of triterpenes [134] such as dammarane, lanostane, lupine, oleanane and ursane types have been isolated and identified [135]. The structures of triterpenoids isolated from Ganoderma spp. are complicated. These compounds consist with lanostane carbon skeleton and pentacyclic triterpenoids (Figure 2). According to the number of carbon atoms in their skeleton, GTs can be divided into three types viz. C30, C27 and C24 [136]. On the basis of the substituent groups, they are classified into different groups such as triterpenoid acids, triterpenoid alcohols and triterpenoid lactones [136].

Figure 2. Chemical structure of lanostane triterpene.

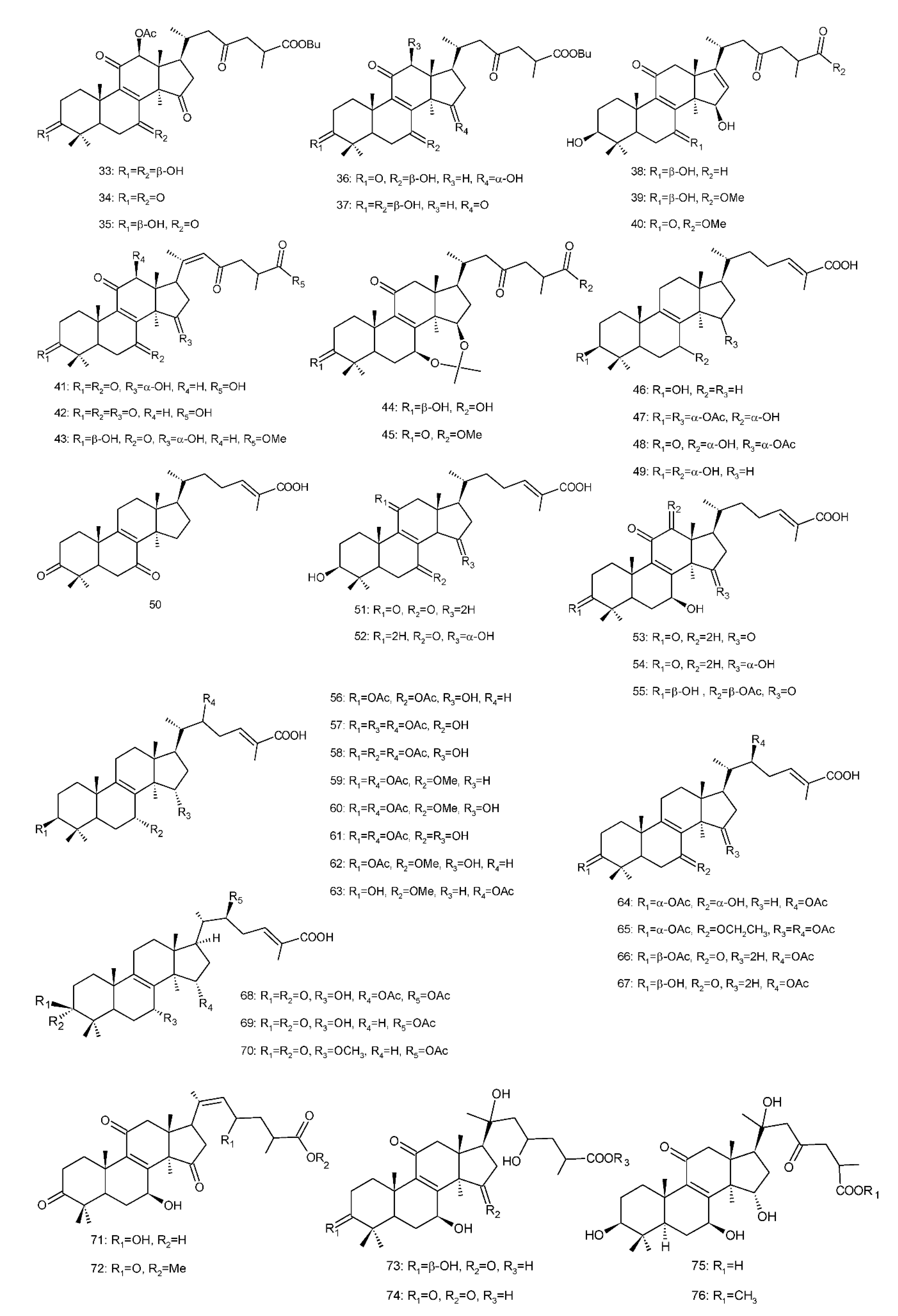

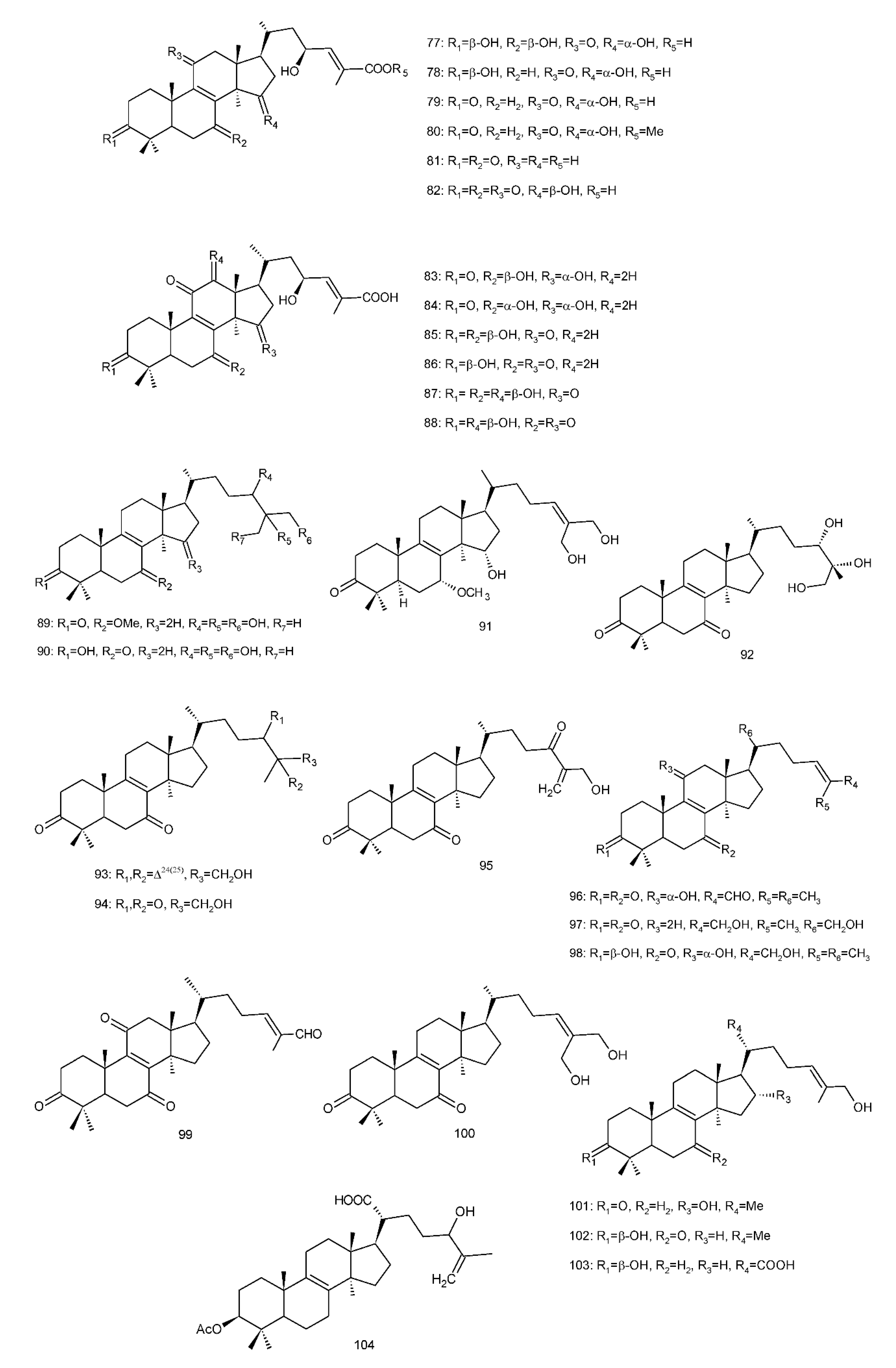

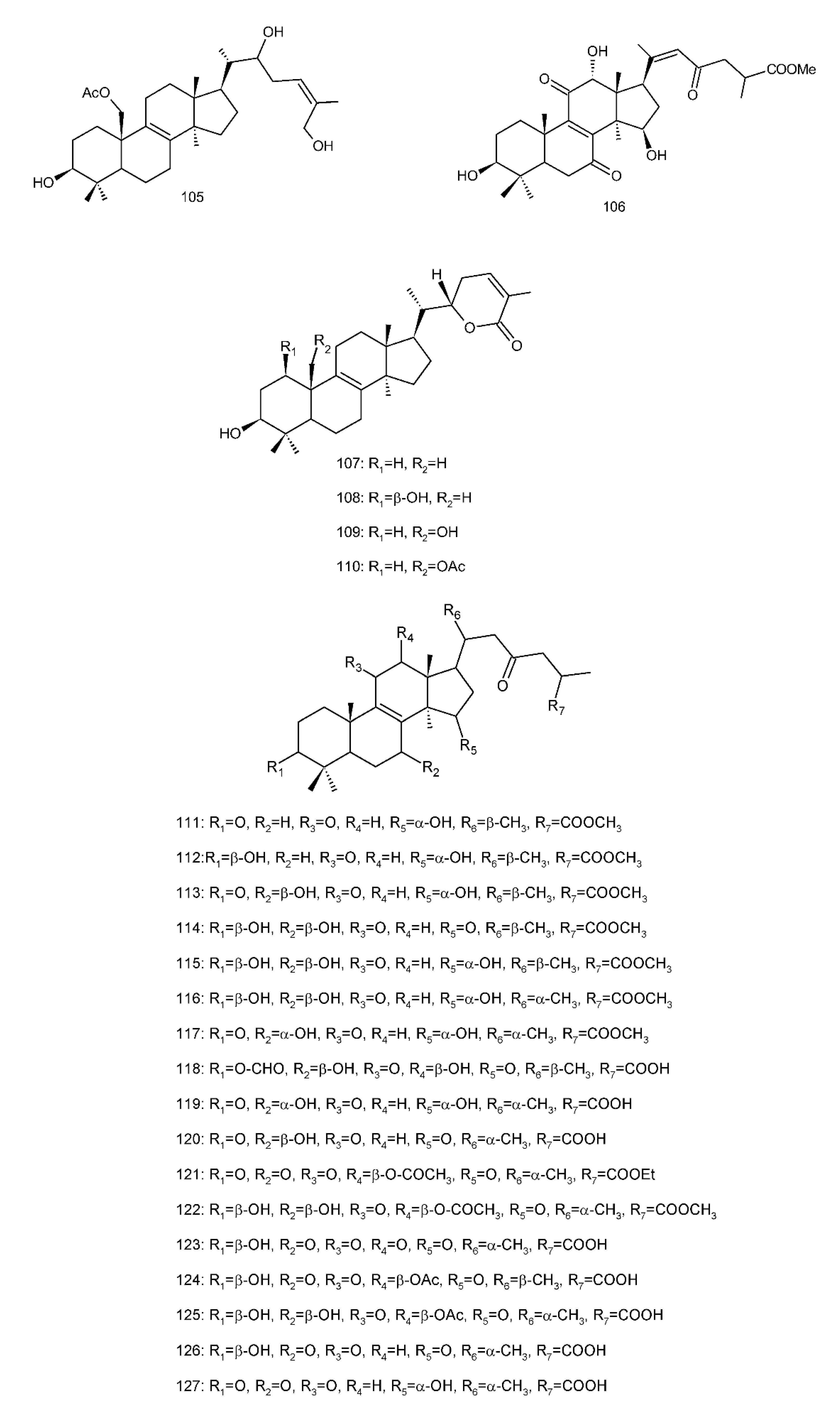

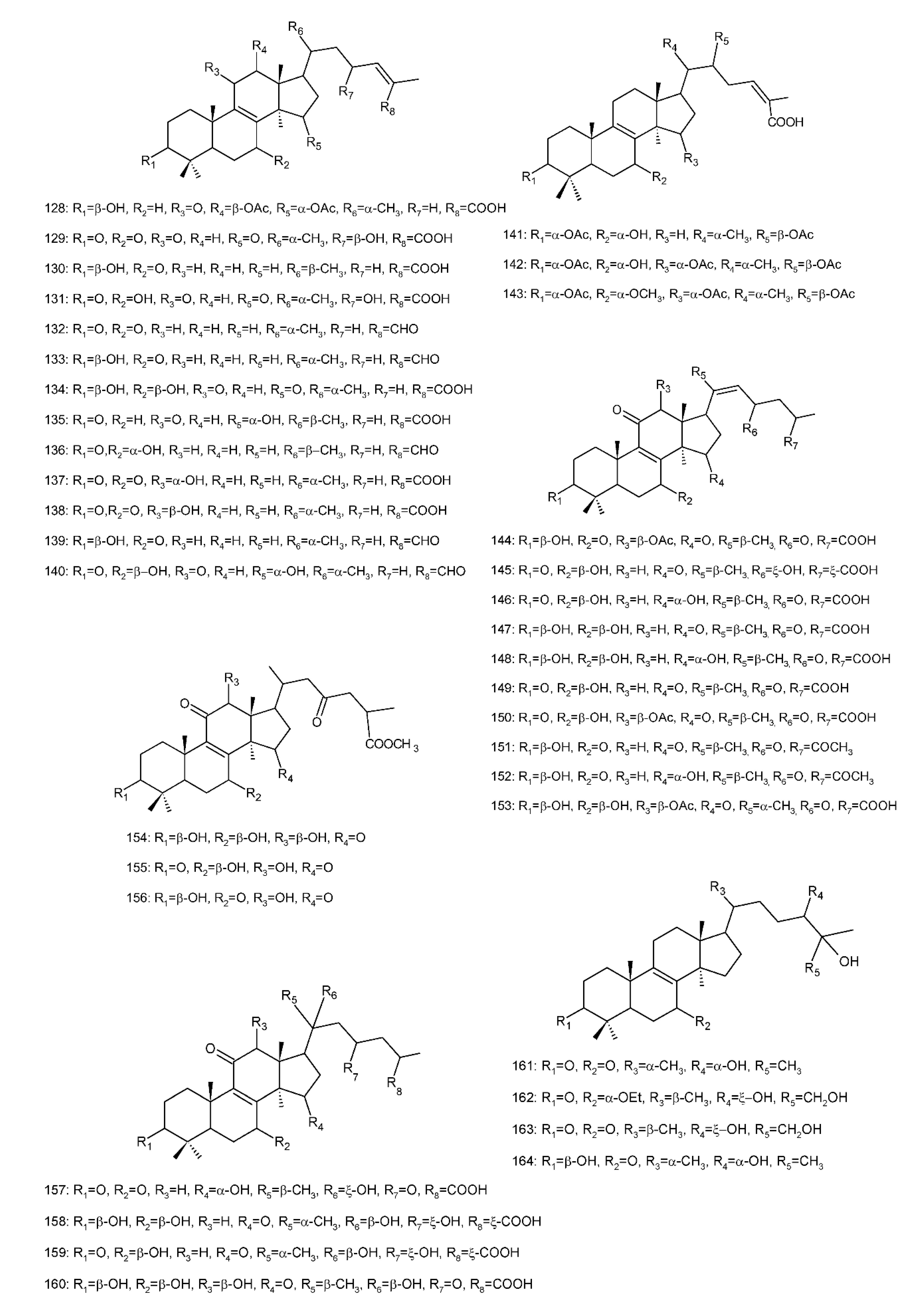

2.2.1. C30 Triterpenoids

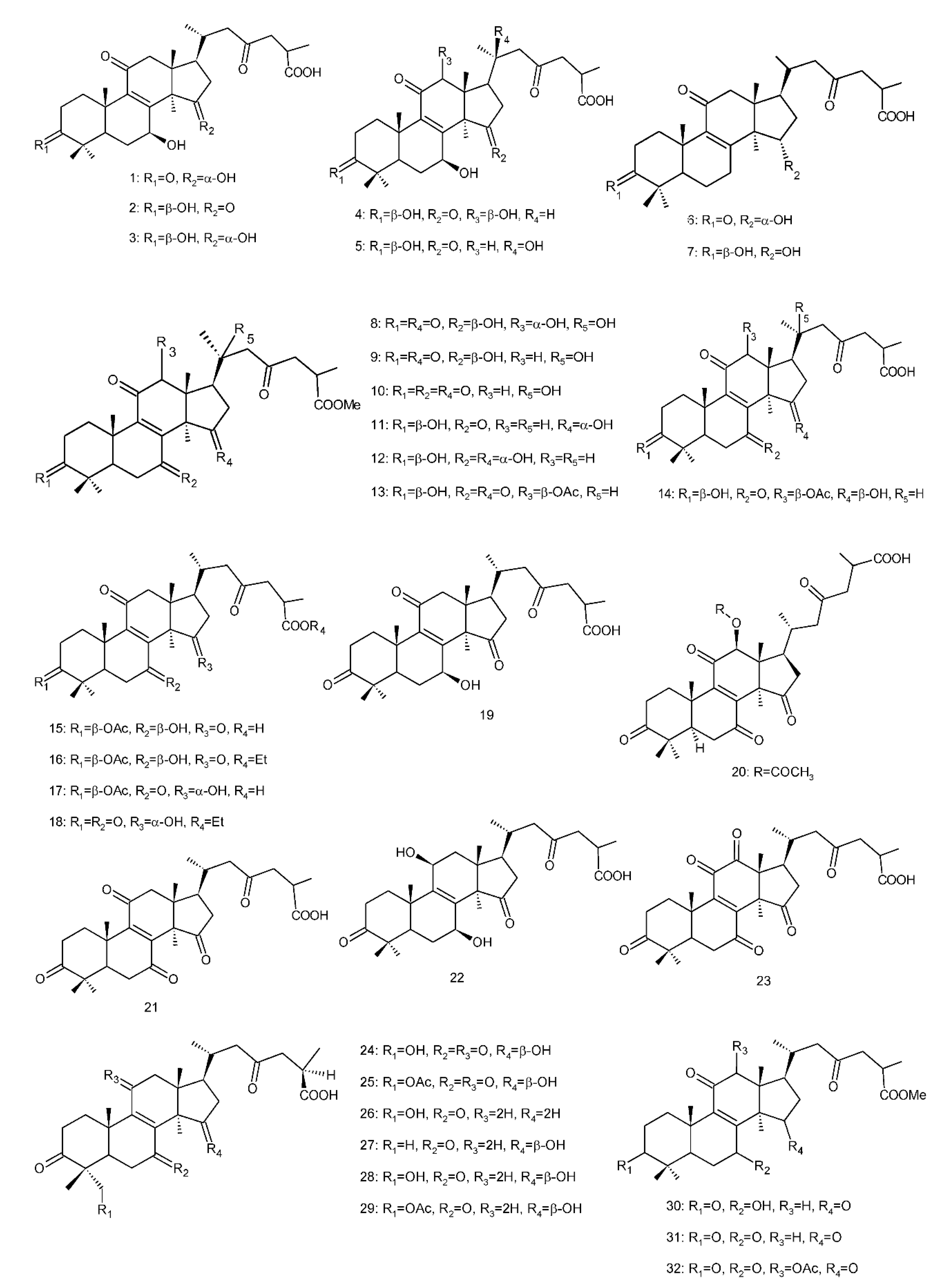

The majority of GTs was C30 triterpenoids on the basis of the biosynthetic pathway of GTs. Because of the oxidation and reduction processes, their structures should be divided into six groups: 8,9-ene, 8,9-dihydro, 8,9-epoxy, 7(8),9(11)-diene, triterpenoid saponins and rearranged novel skeleton triterpenoids.8,9-ene-triterpenoids

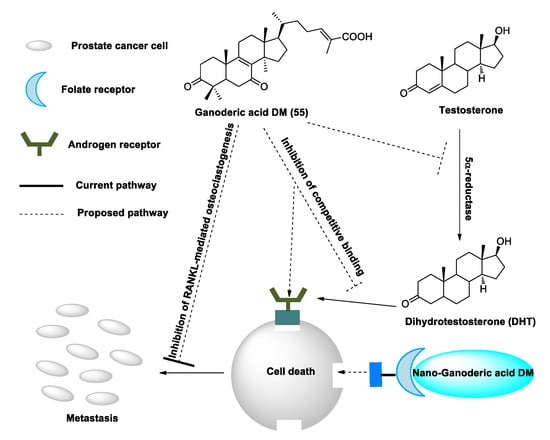

This type of GT is the lanostane-type triterpenoid with a double bond between C-8 and C-9. In addition, C-3, C-7, C-11 and C-15 were generally substituted by the hydroxyl or carbonyl groups. The minority of compounds possessed hydroxyl or carbonyl groups at C-12. Different oxidation and reduction can happen in the side chain. Except the above structural features, compounds ganodermacetal (44) and methyl ganoderate A acetonide (45) possessed an uncommon acetonide unit. Compound 44 was isolated from the basidiomycete G. amboinense, and was a natural product, but not an artefact, which resulted from the acetalization of native ganoderic acid C (3) and with acetone not being used during the isolation procedure [141]. However, compound 45 isolated from the fruiting bodies of G. lucidum was reported to be most likely not of natural origin due to the utilization of acetone during the isolation procedure [142]. Several studies on the bioactivity of triterpenoids showed that ganoderic acids had significant biological activities [95][143][144][145][146][147] (Table 1). Ganoderic acid DM (50) displayed stronger 5α-reductase inhibitory activity (IC50 value of 10.6 μM) than the positive control (α-linolenic acid, 116 μM). Meanwhile, compared to its methyl derivative, the inhibitory activities of 5α-reductase at 20 μM were 55% and 3% for 50 and its derivative, suggesting that the carboxyl group of the side chain for 50 is essential to elicit the inhibitory activity [143]. Liu et al. [144] evaluated the structure –activity relationship for inhibition of 5α-reductase using ganoderic acid A (1), B (2), C (3), D (19), I (5) and DM (50). The results showed that the presence of the carbonyl group at C-3, and of the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group at C-26, was characteristic of almost all inhibitors.Table 1. 8,9-double-bond triterpenoids and bioactivities from Ganoderma.

| No. | Trivial Names | Bioactivities (IC | 50 | /MIC or ED | 50 | ) | Sources | Ganoderma | Species | References | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ganoderic acid A | Promising anticancer agent (via potent inhibitory effect on JAK/STAT3 pathway) | G. lucidum | , | G. tsugae | [148][149][150] | |||||||||||||

| 2. | Ganoderic acid B | Moderately active inhibitor against HIV-1 PR (0.17 mM) | G. lucidum | , | G. tsugae | [148][149][151] | |||||||||||||

| 3. | Ganoderic acid C | Suppressed LPS-induced TNF-α (IC | 50 | = 24.5 µg/mL) production through down-regulating MAPK, NF-kappa B and AP-1 signaling pathways in macrophages | G. lucidum | , | G. tsugae | [148][152] | |||||||||||

| 4. | Ganoderic acid G | Antinociceptive effect | G. lucidum | [153][154] | |||||||||||||||

| 5. | Ganoderic acid I | Cytotoxicity against Hep G2 cells (IC | 50 | = 0.26 mg/mL), HeLa cells (IC | 50 | = 0.33 mg/mL), Caco-2 cells (IC | 50 | = 0.39 mg/mL) | G. lucidum | [153][155] | |||||||||

| 6. | Ganolucidic acid A | - | G. lucidum | [156] | |||||||||||||||

| 7. | Ganolucidic acid B | - | G. lucidum | [157] | |||||||||||||||

| 8. | Methyl ganoderate M | - | G. lucidum | [158] | |||||||||||||||

| 9. | Methyl ganoderate N | - | G. lucidum | [158] | |||||||||||||||

| 10. | Methyl ganoderate O | - | G. lucidum | [158] | |||||||||||||||

| 11. | Methyl ganoderate K | - | G. lucidum | [158] | |||||||||||||||

| 12. | Compound B9 | - | G. lucidum | [158] | |||||||||||||||

| 13. | Methyl ganoderate H | - | G. lucidum | [158] | |||||||||||||||

| 14. | Ganoderic acid | α | Anti-HIV protease (0.19 mM) | G. lucidum | [151] | ||||||||||||||

| 15. | 3-O-acetylganoderic acid B | - | G. lucidum | [159] | |||||||||||||||

| 16. | Ethyl 3-O-acetylganoderate B | - | G. lucidum | [159] | |||||||||||||||

| 17. | 3-O-Acetylganoderic acid K | - | G. lucidum | [159] | |||||||||||||||

| 18. | Ethyl ganoderate J | - | G. lucidum | [159] | |||||||||||||||

| 19. | Ganoderic acid D | Cytotoxicity against HeLa cells (17.3 μM), 5 | α | -reductase inhibition—NE | G. lucidum | , | G. applanatum | , | G. tsugae | [144][148] | [160][161][162] | ||||||||

| 20. | Ganoderic acid F | Cytotoxicity against HeLa cells (19.5 μM) | G. lucidum | [160][162] | |||||||||||||||

| 21. | Ganoderic acid E | Cytotoxicity against tumor cell lines [Hep G2 (1.44 × 10 | −4 | μM), HepG2,2,15 (1.05 × 10 | −4 | μM), κB—NE, CCM2 (31.25 μM), p388 (5.02 μΜ)] | G. lucidum | , | G. tsugae | [148][160] | [163] | ||||||||

| 22. | Ganoderic acid Df | Human aldose reductase inhibitory activity (22.8 μM/mL) | G. lucidum | [164] | |||||||||||||||

| 23. | Ganosporeric acid A | - | G. lucidum | [165] | |||||||||||||||

| 24. | Ganohainanic acid A | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||||||||

| 25. | Acetyl ganohainanic acid A | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||||||||

| 26. | Ganohainanic acid B | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||||||||

| 27. | Ganohainanic acid C | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||||||||

| 28. | Ganohainanic acid D | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||||||||

| 29. | Acetyl ganohainanic acid D | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||||||||

| 30. | Methyl ganoderate D | - | G. lucidum | [166][167] | |||||||||||||||

| 31. | Methyl ganoderate E | - | G. lucidum | [168] | |||||||||||||||

| 32. | Methyl ganoderate F | Inhibitory effects on EBV-EA induction (289 mol ratio/32 pmol TPA) | G. lucidum | [168][169] | |||||||||||||||

| 33. | 12 | β | -Acetoxy-3 | β | ,7 | β | -dihydroxy-11,15,23-trioxolanost-8-en-26-oic acid butyl ester | Antimicrobial [ | Staphylococcus | aureus | ATCC 6538 (68.5 μM) and | Bacillus subtilis | ATCC6633 (123.8 μM)] | G. lucidum | [170] | ||||

| 34. | 12 | β | -acetoxy-3,7,11,15,23-pentaoxolanost-8-en-26-oic acid butyl ester | Antimicrobial—NE | G. lucidum | [170] | |||||||||||||

| 35. | n-Butyl ganoderate H | Selective cholinesterase inhibition | G. lucidum | [142] | |||||||||||||||

| 36. | Butyl ganoderate A | Cytotoxicity against 3T3-L1 cells —NE | G. lucidum | [167] | |||||||||||||||

| 37. | Butyl ganoderate B | Cytotoxicity against 3T3-L1 cells —NE | G. lucidum | [167] | |||||||||||||||

| 38. | 3 | β | ,7 | β | ,15 | β | -Trihydroxy-11,23-dioxo-lanost- 8,16-dien-26-oic acid |

Anti-AChE—NE | G. tropicum | [171] | |||||||||

| 39. | 3 | β | ,7 | β | ,15 | β | -Trihydroxy- 11,23-dioxo-lanost-8,16- dien-26-oic acid methyl ester |

Anti-AChE (15.72%) | G. tropicum | [171] | |||||||||

| 40. | 3 | β | ,15 | β | -Dihydroxy- 7,11,23-trioxo-lanost- 8,16-dien-26-oic acid methyl ester |

Anti-AChE—NE | G. tropicum | [171] | |||||||||||

| 41. | Ganoderenic acid G | - | G. applanatum | [172] | |||||||||||||||

| 42. | Ganoderenic acid F | - | G. applanatum | [172] | |||||||||||||||

| 43. | Methyl ganoderate I | - | G. applanatum | [172] | |||||||||||||||

| 44. | Ganodermacetal | Toxic activity against brine shrimp larvae | G. amboinense | [141] | |||||||||||||||

| 45. | Methyl ganoderate A acetonide | Anti-AChE (18.35 μM), anti-BChE—NE | G. lucidum | [142] | |||||||||||||||

| 46. | Ganoderic acid Z | Cytotoxicity | G. lucidum | [173] | |||||||||||||||

| 47. | Ganoderic acid W | Cytotoxicity | G. lucidum | [173] | |||||||||||||||

| 48. | Ganoderic acid V | Cytotoxicity | G. lucidum | [173] | |||||||||||||||

| 49. | Ganoderic acid U | - | G. lucidum | [174] | |||||||||||||||

| 50. | Ganoderic acid DM | 5 | α | -Reductase inhibition (10.6 μM), anti-androgen and anti-proliferative activities, osteoclastogenesis inhibitor, inhibits prostate cancer cell growth, inhibits breast cancer cell growth |

G. lucidum | , | G. sinense | [95][145] | [146][175] | [176][177] | |||||||||

| 51. | 7-Oxo-ganoderic acid Z | 2 | - | G. resinaceum | [178] | ||||||||||||||

| 52. | 7-Oxo-ganoderic acid Z | 3 | - | G. resinaceum | [178] | ||||||||||||||

| 53. | Ganoderic acid GS-1 | Anti-HIV protease (58 µM) | G. sinense | [177] | |||||||||||||||

| 54. | Ganoderic acid GS-2 | Anti-HIV protease (30 μM) | G. sinense | [177] | |||||||||||||||

| 55. | Ganoderic acid GS-3 | Anti-HIV protease—NE | G. sinense | [177] | |||||||||||||||

| 56. | Ganoderic acid Ma | - | G. lucidum | [179] | |||||||||||||||

| 57. | Ganoderic acid Mb | - | G. lucidum | [179] | |||||||||||||||

| 58. | Ganoderic acid Mc | - | G. lucidum | [179] | |||||||||||||||

| 59. | Ganoderic acid Md | - | G. lucidum | [179] | |||||||||||||||

| 60. | Ganoderic acid Mg | - | G. lucidum | [174] | |||||||||||||||

| 61. | Ganoderic acid Mh | - | G. lucidum | [174] | |||||||||||||||

| 62. | Ganoderic acid Mi | - | G. lucidum | [174] | |||||||||||||||

| 63. | Ganoderic acid Mj | - | G. lucidum | [174] | |||||||||||||||

| 64. | 3 | α | ,22 | β | -Diacetoxy-7 | α | -hydroxyl-5 | α | -lanost-8,24 | E | -dien-26-oic acid | Cytotoxicity against 95D (IC | 50 | = 23 μM/mL), HeLa human tumor cell lines (IC | 50 | = 14.7 μM/mL) | G. lucidum | (mycelia) | [180] |

| 65. | 7-O-Ethyl ganoderic acid O | Cytotoxicity against 95D (46.7 μM), HeLa cells (59.1 μM) | G. lucidum | [181] | |||||||||||||||

| 66. | Ganorbiformin B | - | G. orbiforme | [36] | |||||||||||||||

| 67. | Ganorbiformin C | - | G. orbiforme | [36] | |||||||||||||||

| 68. | Ganorbiformin D | Cytotoxicity (against NCIH187, MCF-7, and κB—NE), nonmalignant Vero cells, antimalarial, antitubercular—NE | G. orbiforme | [36] | |||||||||||||||

| 69. | Ganorbiformin E | Cytotoxicity against NCIH187 (70 µM), MCF-7, κB—NE, nonmalignant Vero cells, antimalarial, antitubercular—NE | G. orbiforme | [36] | |||||||||||||||

| 70. | Ganorbiformin F | Cytotoxicity against NCIH187 (44 µM), MCF-7—NE and κB (63 µM), nonmalignant Vero cells (36 µM), antimalarial, antitubercular—NE | G. orbiforme | [36] | |||||||||||||||

| 71. | 7 | β | ,23 | ξ | -Dihydroxy-3,11,15-trioxolanosta-8,20 | E | (22)-dien-26-oic acid | - | G. applanatum | [38] | |||||||||

| 72. | Methyl ganoderenate D | - | G. applanatum | [38] | |||||||||||||||

| 73. | 3 | β | ,7 | β | ,20,23 | ξ | -Tetrahydroxy-11,15- dioxolanosta-8-en-26-oic acid |

- | G. applanatum | [38] | |||||||||

| 74. | 7 | β | ,20,23 | ξ | -Trihydroxy-3,11,15- trioxolanosta-8-en-26-oic acid |

- | G. applanatum | [38] | |||||||||||

| 75. | Ganoderic acid L | - | G. lucidum | [182] | |||||||||||||||

| 76. | Methyl ganoderate L | - | G. lucidum | [182] | |||||||||||||||

| 77. | Ganolucidic acid γa | PXR-mediated CYP3A4 expression—NE | G. sinense | [183] | |||||||||||||||

| 78. | Ganolucidate F | PXR-mediated CYP3A4 expression | G. sinense | [183] | |||||||||||||||

| 79. | Ganolucidic acid D | Cytotoxicity on tumor growth cells—NE | G. lucidum | [182][184] | |||||||||||||||

| 80. | Methyl ganolucidate D | - | G. lucidum | [182] | |||||||||||||||

| 81. | Hainanic acid A | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||||||||

| 82. | Hainanic acid B | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||||||||

| 83. | Ganoderic acid γ | Cytotoxicity against tumor cell growth Meth-A (ED | 50 | = 15.6 μg/mL), LLC—NE | G. lucidum | [184] | |||||||||||||

| 84. | Ganoderic acid δ | Cytotoxicity against tumor cell growth Meth-A and LLC—NE | G. lucidum | [184] | |||||||||||||||

| 85. | Ganoderic acid ε | Cytotoxicity against tumor cell growth Meth-A (ED | 50 | = 12.2 μg/mL), LLC—NE | G. lucidum | [184] | |||||||||||||

| 86. | Ganoderic acid ζ | Cytotoxicity against tumor cell growth Meth-A and LLC—NE | G. lucidum | [184] | |||||||||||||||

| 87. | Ganoderic acid η | Cytotoxicity against tumor cell growth Meth-A and LLC—NE | G. lucidum | [184] | |||||||||||||||

| 88. | Ganoderic acid θ | Cytotoxicity against tumor cell growth Meth-A (ED | 50 | = 5.7 μg/mL), LLC (ED | 50 | = 15.2 μg/mL) | G. lucidum | [184] | |||||||||||

| 89. | Ganoderiol G | - | G. lucidum | [185] | |||||||||||||||

| 90. | Ganoderiol H | - | G. lucidum | [185] | |||||||||||||||

| 91. | Ganoderiol I | - | G. lucidum | [185] | |||||||||||||||

| 92. | 24 | S | ,25 | R | -Dihydroxy-3,7-dioxo-8-en-5 | α | -lanost-26-ol | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||

| 93. | Ganoderone A | Antiviral: influenza A—NE, HSV (0.3 μg/mL) | G. pfeifferi | [46] | |||||||||||||||

| 94. | Ganoderone C | Antiviral—NE | G. pfeifferi | [46] | |||||||||||||||

| 95. | 3,7,24-Trioxo-5 | α | -lanost- 8,25-dien-26-ol |

Cytotoxicity against HL-60 (15.70 µM), SMMC-7721 (15.52 µM), A-549 (15.81 µM), MCF-7 (20.08 µM), SW480—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||||||

| 96. | Hainanaldehyde A | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||||||||

| 97. | 21-Hydroxy-3,7-dioxo-5 | α | -lanost-8,24 | E | -dien-26-ol | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||||||

| 98. | 3 | β | ,11 | α | -Dihydroxy-7-oxo-5 | α | -lanost-8,24 | E | -dien-26-ol | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. hainanense | [62] | |||||||

| 99. | Lucialdehyde D | - | G. lucidum | , | G. pfeifferi | [46][186] | [187] | ||||||||||||

| 100. | Ganoderiol J | - | G. sinense | [183] | |||||||||||||||

| 101. | 16 | α | ,26-Dihydroxylanosta-8,24-dien-3-one | Cytotoxicity against K-562 cells (13.3 μg/mL) | G. hainanense | [75] | |||||||||||||

| 102. | Lucidadiol | Antiviral: influenza virus type A (ED | 50 | = 0.22 mmol/L), HSV—NE |

G. lucidum | , | G. pfeifferi | [188][189] | |||||||||||

| 103. | Sinensoic acid | - | G. sinense | [190] | |||||||||||||||

| 104. | Tsugaric acid C | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. tsugae | [191] | |||||||||||||||

| 105. | Colossolactone A | Moderate cytotoxicity against L-929, K-562, HeLa cells—NE, anti-inflammatory properties | G. colossum | [192] | |||||||||||||||

| 106. | Ganoderenicfy A | Promoting angiogenesis activities | G. applanatum | [193] | |||||||||||||||

| 107. | Colossolactone I | Moderate cytotoxicity against HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells, Antimalarial: | Plasmodium falciparum | —NE | G. colossum | [194][195] | [196] | ||||||||||||

| 108. | Colossolactone II | Low cytotoxicity against HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells | G. colossum | [194][195] | |||||||||||||||

| 109. | Ganodermalactone E | Antimalarial: | Plasmodium falciparum | —NE | G. colossum | [196] | |||||||||||||

| 110. | Colossolactone B | Moderate cytotoxicity against L-929, K-562, and HeLa cells, antimicrobial—NE, antibacterial—NE | G. colossum | [192][196] | [197] | ||||||||||||||

| 111. | Methyl ganolucidate A | - | G. lucidum | [153][157] | |||||||||||||||

| 112. | Methyl ganolucidate B | - | G. lucidum | [153][157] | |||||||||||||||

| 113. | Methyl ganoderate A | - |

G. lucidum | [166] | |||||||||||||||

| 114. | Methyl ganoderate B | - | G. lucidum | [166] | |||||||||||||||

| 115. | Methyl ganoderate C | - | G. lucidum | [166] | |||||||||||||||

| 116. | Methyl ganoderate C | 2 | - | G. lucidum | (dried fruit bodies) |

[198] | |||||||||||||

| 117. | Compound B | 8 | - | G. lucidum | (dried fruit bodies) |

[198] | |||||||||||||

| 118. | 3 | β | -Oxo-formyl-7 | β | ,12 | β | -dihydroxy-5 | α | -lanost-11,15,23-trioxo-8-en( | E | )-26-oic acid | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[199] | ||||

| 119. | Ganoderic acid B | 8 | Cytotoxicity against LLC—NE, T47-D—NE, S-180—NE, Meth-A—NE | G. lucidum | ( | fruit bodies) | [200] | ||||||||||||

| 120. | Ganoderic acid C | 1 | Inhibitory activity against HIV-PR (0.18 mM) | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[151][200] | |||||||||||||

| 121. | 12 | β | -Acetoxy-3,7,11,15,23-pentaoxo-5 | α | -lanosta-8-en-26-oic acid ethyl ester | Cytotoxicity against human HeLa cervical cancer cell lines (63 μM) | G. lucidum | [201] | |||||||||||

| 122. | 3 | β | ,7 | β | -Dihydroxy-12 | β | -acetoxy-11,15,23-trioxo-5 | α | -lanosta-8-en-26-oic acid methyl ester | - | G. lucidum | [32] | |||||||

| 123. | 3 | β | -Hydroxy-7,11,12,15,23-pentaoxolanost-8-en-26-oic acid | Cytotoxic against p388 cell (9.85 μM), HeLa cell (17.10 μM), BEL-7402 cell (51.00 μM), SGC-7901 cells (42.00 μM) |

G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[202] | ||||||||||||

| 124. | Ganoderic acid H | Inhibitory activity against HIV-PR (0.20 mM) | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[160][203] | ||||||||||||||

| 125. | Ganoderic acid K | Cytotoxicity against p388 cell (13. 8 μM), HeLa cell (8.23 μM); BEL-7402 cell (16.5 μM), SGC-7901cell (21.0 μM) |

G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[204] | ||||||||||||||

| 126. | Ganoderic acid AM | 1 | Cytotoxicity against p388 cell (13. 2 μM), HeLa cell (9.75 μM), BEL-7402 cell (20.9 μM), SGC-7901 cell (23.0 μM) |

G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[204] | |||||||||||||

| 127. | Ganoderic acid J | Cytotoxicity against p388 cell (15. 8 μM), HeLa cell (12.2 μM), BEL-7402 cell (25.2 μM), SGC-7901 cell (20.2 μM) |

G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[204] | ||||||||||||||

| 128. | Ganoderic acid AP | 2 | - | G. applanatum | (fruit bodies) |

[161] | |||||||||||||

| 129. | 23 | S | -Hydroxy-3,7,11,15-tetraoxolanost-8,24 | E | -diene-26-oic acid | Cytotoxicity against p388 cell (15.7 μM), HeLa cell (9.72 μM), BEL-7402 cell (25.6 μM), SGC-7901 cell (23.1 μM) | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[204] | ||||||||||

| 130. | 7-Oxoganoderic acid Z | Inhibitory activities against the HMG-CoA reductase (22.3 μM), acyl CoA acyltransferase (5.5 μM) |

G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[205] | ||||||||||||||

| 131. | Ganoderic acid LM | 2 | Potent enhancement of ConA-induced mice splenocytes proliferation in vitro | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[206] | |||||||||||||

| 132. | Lucialdehyde B | Cytotoxic effect on tested tumor cells | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[200] | ||||||||||||||

| 133. | Lucialdehyde C | Cytotoxicity against LLC, T-47D (10.7 µg/mL), Sarcoma 180 (4.7 µg/mL), Meth-A tumor cells (3.8 µg/mL) |

G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[200] | ||||||||||||||

| 134. | Ganoderic acid | β | HIV-I protease inhibitory activity (20 µM) | G. lucidum | (spores) | [207] | |||||||||||||

| 135. | Ganolucidic acid E | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[185] | ||||||||||||||

| 136. | Ganoderal B | - | G. lucidum | [208] | |||||||||||||||

| 137. | 11 | α | -Hydroxy-3,7-dioxo-5 | α | -lanosta-8,24( | E | )-dien-26-oic acid | Cytotoxicity against human HeLa cervical cancer cell lines (123 μM) | G. lucidum | [201] | |||||||||

| 138. | 11 | β | -Hydroxy-3,7-dioxo-5 | α | -lanosta-8,24( | E | )-dien-26-oic acid | Cytotoxicity against human HeLa cervical cancer cell lines (51 μM) | G. lucidum | [201] | |||||||||

| 139. | Lucidal | - | G. lucidum | (cultured fruit bodies) |

[188] | ||||||||||||||

| 140. | Lucialdehyde E | Cytotoxic activity against esophageal tumor EC109 cell line (18.7 mg/mL) | G. lucidum | (spores) | [187] | ||||||||||||||

| 141. | 3 | α | ,22 | β | -Diacetoxy-7 | α | -hydroxyl-5 | α | -lanost-8,24 | E | -dien-26-oic acid | Cytotoxicity against HeLa cell lines (14.7 μM), 95D cell lines (23.01 μM) | G. lucidum | (mycelial mat) |

[180] | ||||

| 142. | Ganoderic acid O | - | G. lucidum | (cultured mycelium) |

[209] | ||||||||||||||

| 143. | 7-O-Methylganoderic acid O | - | G. lucidum | (cultured mycelium) |

[209] | ||||||||||||||

| 12 | β | -Acetoxy-3 | β | -hydroxy-7,11,15,23- tetraoxo-lanost-8,20 | E | -diene-26-oic acid | Cytotoxicity against human cancer cell p388 (12.7 µM), HeLa cell (8.72 µM), BEL-7402 (24.2 µM), SGC-7901 (18.7 µM) | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[204] | |||||||||

| 145. | 23-Dihydroganoderenic acid D | - | G. applanatum | (fruit bodies) |

[38] | ||||||||||||||

| 146. | Ganoderenic acid A | - | G. lucidum | (dried fruit bodies) |

[160] | ||||||||||||||

| 147. | Ganoderenic acid B | - | G. lucidum | (dried fruit bodies) |

[160] | ||||||||||||||

| 148. | Ganoderenic acid C | - | G. lucidum | (dried fruit bodies) |

[160] | ||||||||||||||

| 149. | Ganoderenic acid D | - | G. lucidum | (dried fruit bodies) |

[160] | ||||||||||||||

| 150. | 12 | β | -Acetoxy-7 | β | -hydroxy-3,11,15,23- tetraoxo-5 | α | -lanosta-8,20-dien-26-oic acid | Cytotoxicity against human HeLa cervical cancer cell lines—NE | G. lucidum | [201] | |||||||||

| 151. | Methy ganoderenate H | - | G. applanatum | (fruit bodies) |

[172] | ||||||||||||||

| 152. | Methyl ganoderenate I | - | G. applanatum | (fruit bodies) |

[172] | ||||||||||||||

| 153. | 12 | β | -Acetoxy-3 | β | ,7 | β | -dihydroxy-11,15,23-trioxo-5 | α | -lanosta-8,20-dien-26-oic acid | - | G. lucidum | [32] | |||||||

| 154. | Methyl ganoderate G | - | G. lucidum | [153] | |||||||||||||||

| 155. | Compound C5 | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[203] | ||||||||||||||

| 156. | Compound C6 | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[203] | ||||||||||||||

| 157. | Ganoderic acid AP | 3 | - | G. applanatum | (fruit bodies) |

[161] | |||||||||||||

| 158. | 23-Dihydroganoderic acid I | - | G. applanatum | (fruit bodies) |

[38] | ||||||||||||||

| 159. | 23-Dihydroganoderic acid N | - | G. applanatum | (fruit bodies) |

[38] | ||||||||||||||

| 160. | 20-Hydroxylganoderic acid G | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[210] | ||||||||||||||

| 161. | Lucidumol A | HIV-I protease inhibitory activity—NE | G. lucidum | (spores) | [207] | ||||||||||||||

| 162. | Ganoderiol C | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[185] | ||||||||||||||

| 163. | Ganoderiol D | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[185] | ||||||||||||||

| 164. | Ganoderitriol M | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[211] | ||||||||||||||

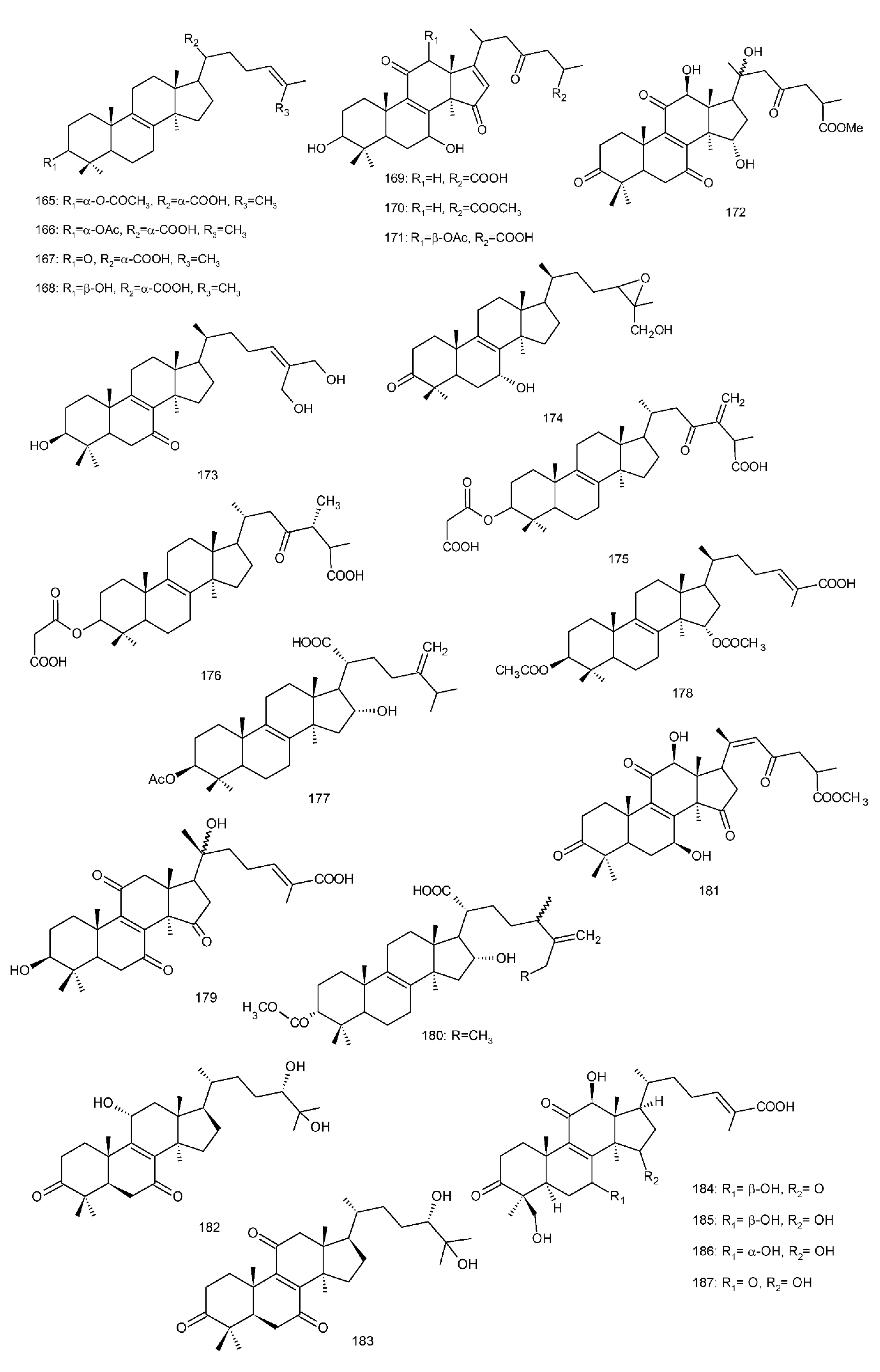

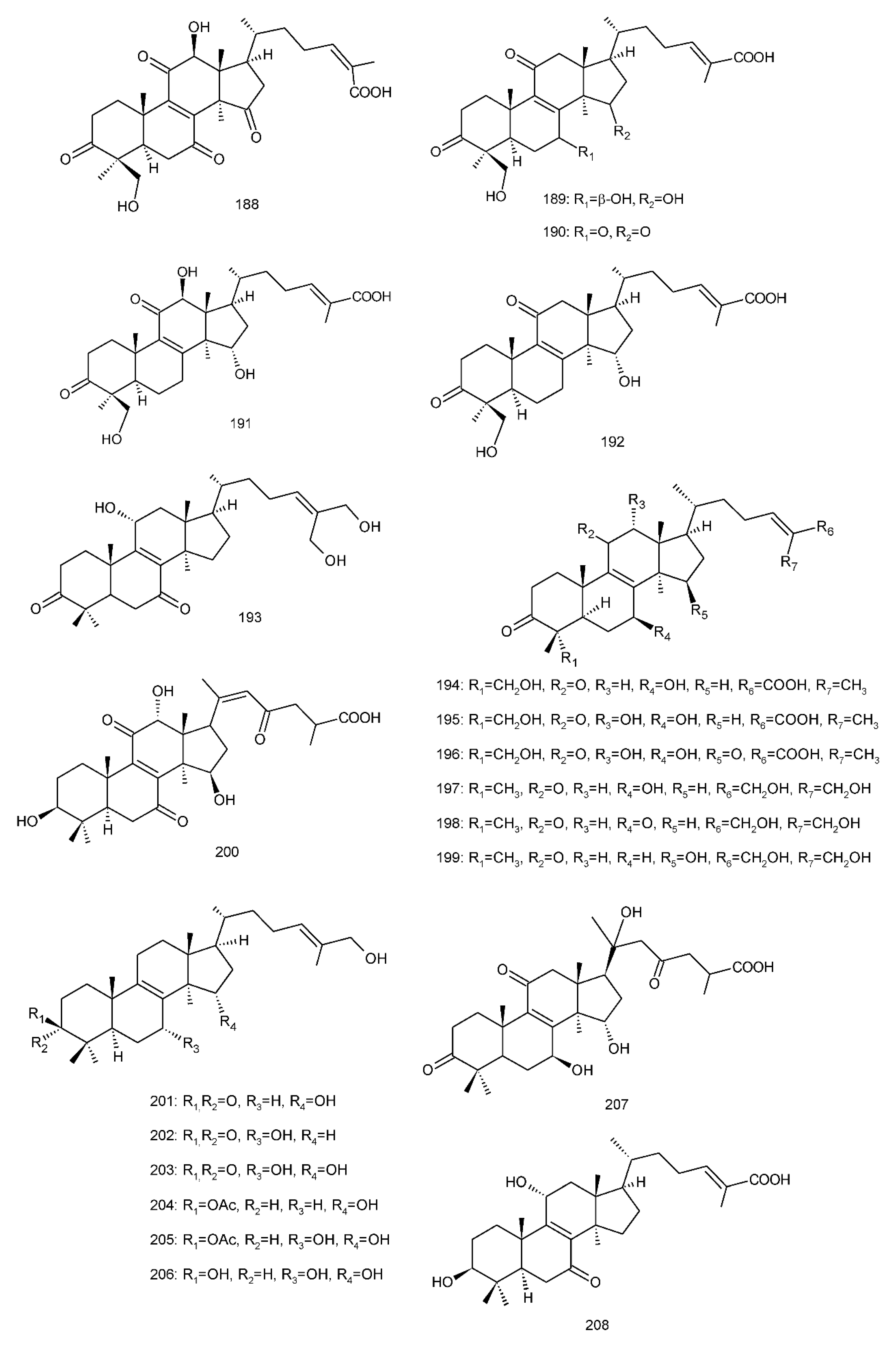

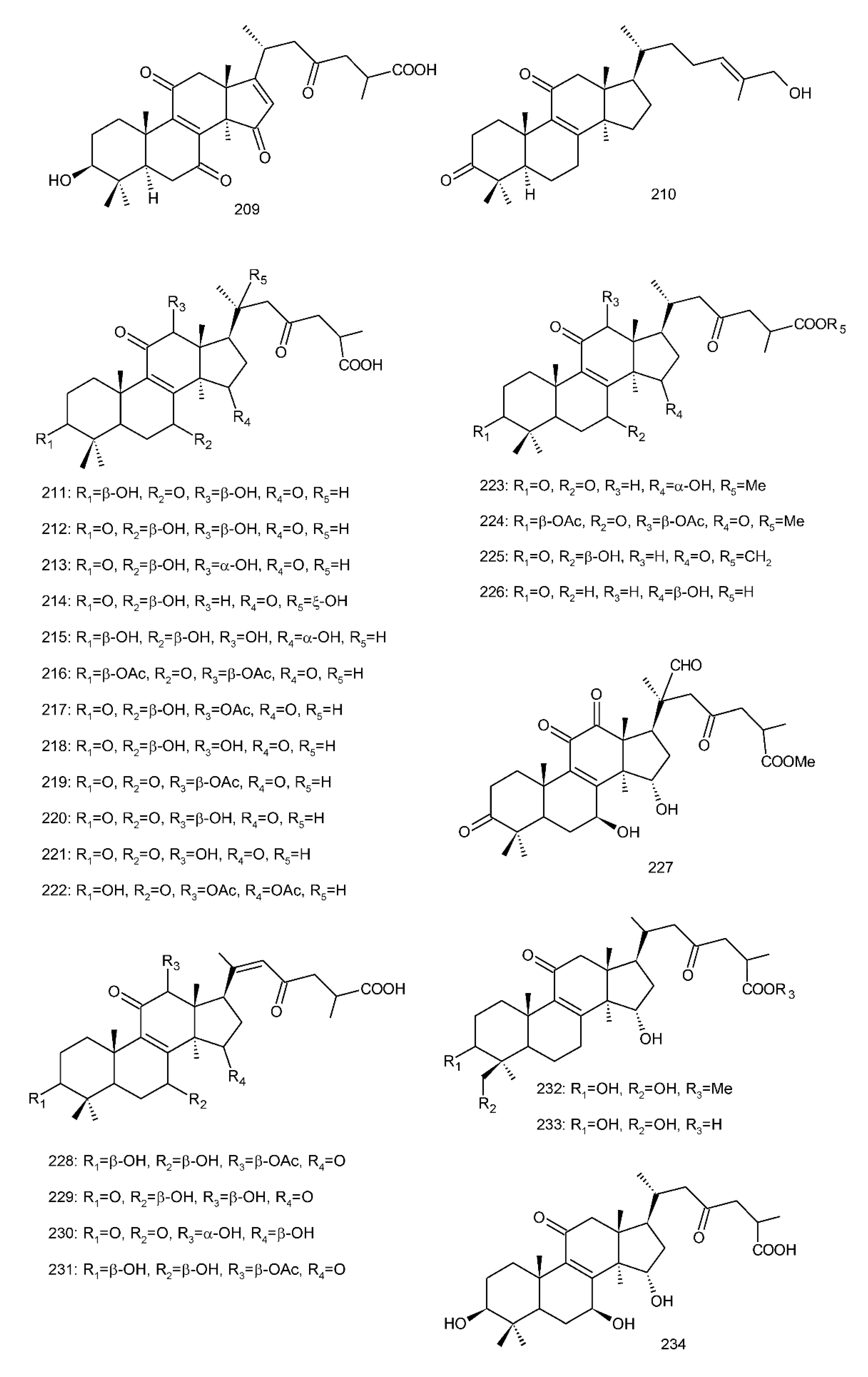

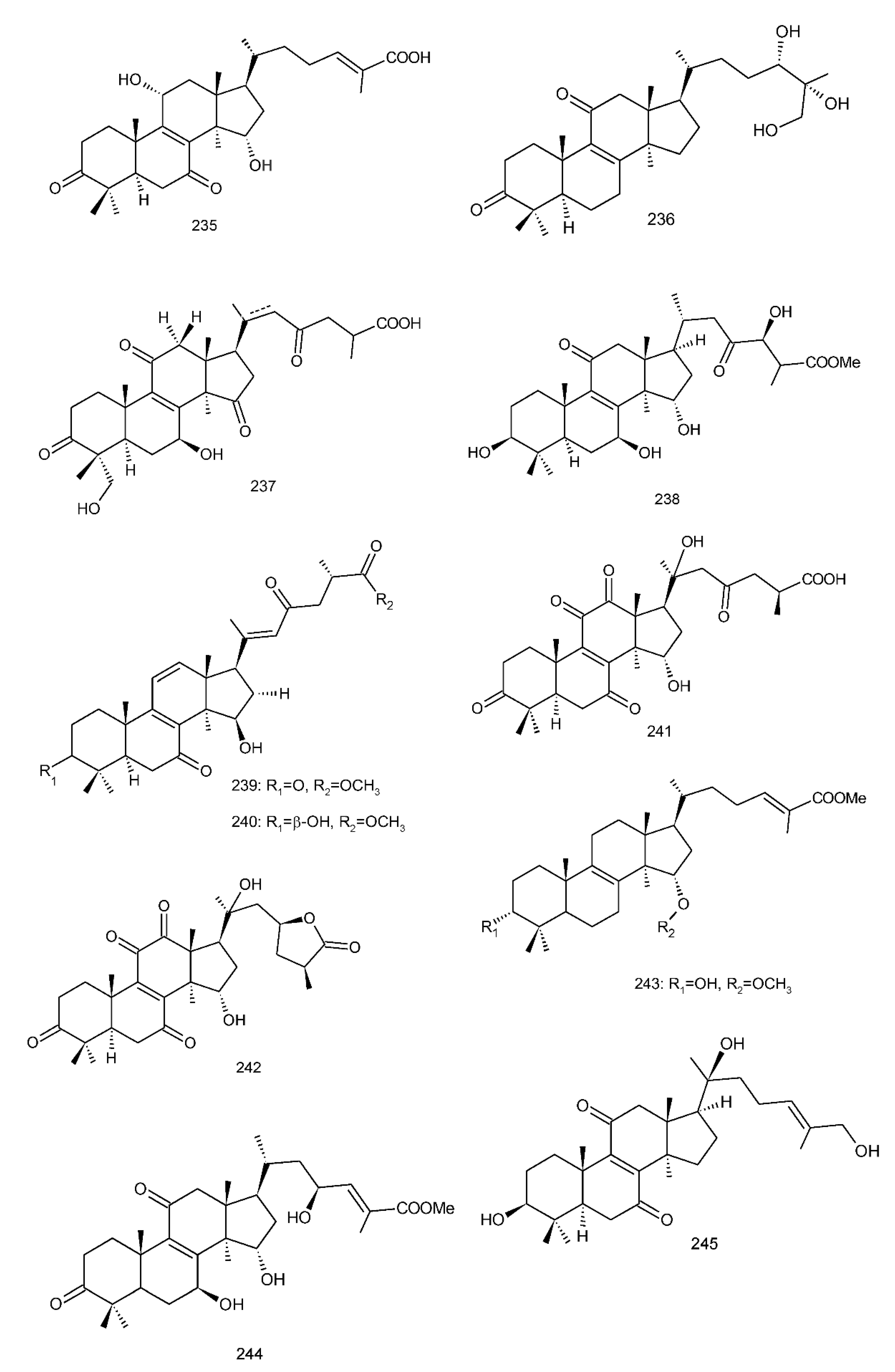

| 165. | Tsugaric acid A | - | G. tsugae | [212] | |||||||||||||||

| 166. | Tsugarioside A | Cytotoxicity against PLC/PRF/5 (ED | 50 | = 6.5 μg/mL), T-24 (ED | 50 | = 8.6 μg/mL), HT-3 (ED | 50 | = 7.2 μg/mL), SiHa (ED | 50 | = 9.5 μg/mL) | G. tsugae | (fruit bodies) |

[191] | ||||||

| 167. | 3-Oxo-5 | α | -lanosta-8,24-dien-21-oic acid | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. resinaceum | (fruit bodies) |

[213] | ||||||||||||

| 168. | 3 | β | -Hydroxy-5α-lanosta-8,24-dien-21-oic acid | Cytotoxicity against T-24 (ED | 50 | = 4.4 μg/mL), HT-3 (ED | 50 | = 3.5 μg/mL), SiHa (ED | 50 | = 5.5 μg/mL), CaSKi (ED | 50 | = 6.2 μg/mL) | G. tsugae | (fruit bodies) |

[191] | ||||

| 169. | 3 | β | ,7 | β | -Dihydroxy-11,15,23-trioxolanost-8,16-dien-26-oic acid | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[188] | ||||||||||

| 170. | 3 | β | ,7 | β | -Dihydroxy-11,15,23-trioxolanost-8,16-dien-26-oic acid methyl ester | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[188] | ||||||||||

| 171. | 12 | β | -Acetoxy-3 | β | ,7 | β | -dihydroxy-11,15,23-trioxolanost-8,16-dien-26-oic acid | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[214] | ||||||||

| 172. | Methyl ganoderate AP | - | G. applanatum | (fruit bodies) |

[172] | ||||||||||||||

| 173. | Ganoderiol E | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[185] | ||||||||||||||

| 174. | Epoxyganoderiol A | - | G. lucidum | [208] | |||||||||||||||

| 175. | 3 | α | -Carboxyacetoxy-24-methylene-23-oxolanost-8-en-26-oic acid | Cytotoxicity—NE | G. applanatum | (fruit bodies) |

[215] | ||||||||||||

| 176. | 3 | α | -Carboxyacetoxy-24-methyl-23- oxolanost-8-en-26-oic acid |

Cytotoxicity—NE | G. applanatum | (fruit bodies) |

[215] | ||||||||||||

| 177. | 3-Epipachymic acid | - | G. resinaceum | (fruit bodies) |

[213] | ||||||||||||||

| 178. | 3 | β | ,15 | α | -Diacetoxylanosta-8,24-dien-26-oic acid | - | G. lucidum | (mycelia) | [216] | ||||||||||

| 179. | Ganoderic acid V | 1 | - | G. lucidum | [217] | ||||||||||||||

| 180. | Tsugaric acid B | - | G. tsugae | [212] | |||||||||||||||

| 181. | Methyl ganoderenate E | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[158] | ||||||||||||||

| 182. | Lucidumol D | Selective anti-proliferative and cytotoxic effects | G. lingzhi | [218] | |||||||||||||||

| 183. | Lucidumol C | Selective anti-proliferative and cytotoxic effects | G. lingzhi | [218] | |||||||||||||||

| 184. | Leucocontextin A | - | G. leucocontextum | [219] | |||||||||||||||

| 185. | Leucocontextin B | - | G. leucocontextum | [219] | |||||||||||||||

| 186. | Leucocontextin C | - | G. leucocontextum | [219] | |||||||||||||||

| 187. | Leucocontextin D | - | G. leucocontextum | [219] | |||||||||||||||

| 188. | Leucocontextin E | - | G. leucocontextum | [219] | |||||||||||||||

| 189. | Leucocontextin F | - | G. leucocontextum | [219] | |||||||||||||||

| 190. | Leucocontextin G | - | G. leucocontextum | [219] | |||||||||||||||

| 191. | Leucocontextin H | - | G. leucocontextum | [219] | |||||||||||||||

| 192. | Leucocontextin I | - | G. leucocontextum | [219] | |||||||||||||||

| 193. | Leucocontextin R | Cytotoxicity against K562 and MCF-7 cell lines (IC | 50 | = 20–30 μM) | G. leucocontextum | [219] | |||||||||||||

| 194. | Ganoleuconin A | Cytotoxicity against K562 (17.8 μM), PC-3 cell lines—NE | G. leucocontextum | [34] | |||||||||||||||

| 195. | Ganoleuconin B | Cytotoxicity against K562 (19.7 μM), PC-3 cell lines—NE | G. leucocontextum | [34] | |||||||||||||||

| 196. | Ganoleuconin E | Cytotoxicity against K562 and PC-3 cell lines—NE | G. leucocontextum | [34] | |||||||||||||||

| 197. | Ganoleuconin G | Cytotoxicity against K562 (11.4 μM), PC-3 cell lines (132.4 μM) | G. leucocontextum | [34] | |||||||||||||||

| 198. | Ganoleuconin H | Cytotoxicity against K562 (115.4 μM), PC-3 cell lines (24.2 μM) | G. leucocontextum | [34] | |||||||||||||||

| 199. | Ganoleuconin I | Cytotoxicity against K562 and PC-3 cell lines—NE | G. leucocontextum | [34] | |||||||||||||||

| 200. | Ganoderenicfy B | Promoting angiogenesis activities | G. applanatum | [193] | |||||||||||||||

| 201. | ( | 24E | )-15 | α | ,26-Dihydroxy-3-oxo-lanosta-8,24-diene | Antimycobacteria (50 μg/mL), cytotoxicity (5.9 μg/mL) | G. casuarinicola | [220] | |||||||||||

| 202. | ( | 24E | ) | - | 7 | α | ,26-Dihydroxy-3-oxo-lanosta-8,24-diene. | Antimalarial activity (IC | 50 | = 9.7 μg/mL) | G. casuarinicola | [220] | |||||||

| 203. | ( | 24E | ) | - | 3-Oxo-7 | α | ,15 | α | ,26-trihy-droxylanosta-8,24-diene | Antimalarial activity (IC | 50 | = 9.2 μg/mL) | G. casuarinicola | [220] | |||||

| 204. | ( | 24E | ) | - | 3 | β | -Acetoxy-15 | α | ,26-dihydroxylanosta-8,24-diene | Antimycobacteria (25 μg/mL), cytotoxicity (6 μg/mL) | G. casuarinicola | [220] | |||||||

| 205. | ( | 24E | ) | - | 3 | β | - | A | cetoxy-7 | α | ,15 | α | ,26- trihydroxylanosta-8,24-diene |

Antimycobacteria (25 μg/mL), cytotoxicity (9 μg/mL) | G. casuarinicola | [220] | |||

| 206. | ( | 24E | ) | - | 3 | β | ,7 | α | ,15 | α | ,26-Tetra-hydroxylanosta-8,24-diene | - | G. casuarinicola | [220] | |||||

| 207. | 7 | β | ,15 | α | ,20-Trihydroxy-3,11,23-trioxo-5α-lanosta-8-en-26-oic acid | - | G. lucidum | [221] | |||||||||||

| 208. | Ganoderic acid XL | 3 | - | G. theaecolum | [222] | ||||||||||||||

| 209. | Ganoderic acid XL | 4 | - | G. theaecolum | [222] | ||||||||||||||

| 210. | Ganodecalone A | Cytotoxicity against K562 (17.22 µM) | G. calidophilum | [53] | |||||||||||||||

| 211. | Ganoderic acid C | 6 | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | |||||||||||||

| 212. | Ganoderic acid D | 1 | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | |||||||||||||

| 213. | Ganoderic acid M | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 214. | Ganoderic acid N | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 215. | 12-Hydroxylganoderic acid C | 2 | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | |||||||||||||

| 216. | 3-Acetylganoderic acid H | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 217. | 12-Acetoxyganoderic acid D | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 218. | 12-Hydroxyganoderic acid D | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 219. | 12-Acetoxyganoderic acid F | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 220. | 12 | β | -Hydroxy-3,7,11,15,23-pentaoxo-5 | α | -lanosta-8-en-26-oic acid | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||

| 221. | 12-Hydroxy-3,7,11,15,23-pentaoxo-lanost-8-en-26-oic acid | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 222. | 12,15-Bis(acetyloxy)-3-hydroxy-7,11,23-trioxo-lanost-8-en-26-oic acid | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 223. | Methyl ganoderate J | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 224. | Methyl-O-acetylganoderate C | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 225. | Methyl ganoderate C1 | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 226. | Methyl ganoderate AM | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 227. | Ganoderic aldehyde A | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 228. | Ganoderenic acid K | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 229. | Ganoderenic acid E | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 230. | Elfvingic acid A | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 231. | 12 | β | -Acetoxy-3 | β | ,7 | β | -dihydroxy-11,15,23-trioxo-5 | α | -lanosta-8,20-dien-26-oic acid | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||

| 232. | Methyl ganolucidate C | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 233. | Ganolucidic acid C | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies) |

[65] | ||||||||||||||

| 234. | Ganoderic acid C | 2 | - | G. lucidum | (fruit bodies /spore) |

[65] | |||||||||||||

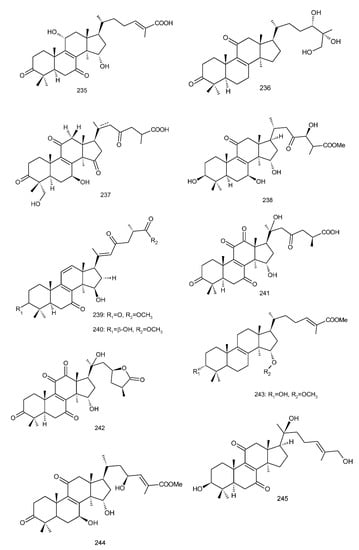

| 235. | Ganodrol A | Moderately inhibits FAAH (Inhibition rate in between 50–60%) | G. lucidum | [116] | |||||||||||||||

| 236. | Ganodrol C | Moderately inhibits FAAH (Inhibition rate in between 50–60%) | G. lucidum | [116] | |||||||||||||||

| 237. | Ganodrol D | Moderately inhibits FAAH (Inhibition rate in between 30–40%) | G. lucidum | [116] | |||||||||||||||

| 238. | Ganoderic acid XL | 5 | Cytotoxicity against human tumor cell lines—NE | G. theaecolum | [222] | ||||||||||||||

| 239. | Methyl gibbosate M | Anti-adipogenesis activity—NE | G. applanatum | [51] | |||||||||||||||

| 240. | Methyl ganoapplate E | Anti-adipogenesis activity—NE | G. applanatum | [51] | |||||||||||||||

| 241. | Applandiketone A | - | G. applanatum | [223] | |||||||||||||||

| 242. | Applandiketone B | Significant inhibitory effect against NO production in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells (IC | 50 | = 20.65 µM) | G. applanatum | [223] | |||||||||||||

| 243. | 15 | α | -Acetoxy-3 | α | -hydroxylanota- 8,24-dien-26-oic |

- | G. capense | [224] | |||||||||||

| 244. | Ganoderterpene A | Strongly suppressed NO generation in BV-2 microglial cells treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (IC | 50 | = 7.15 µM), significantly suppressed the activation of MAPK and TLR-4/NF-κB signaling pathways, effectively improved the LPS-induced mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptosis | G. lucidum | [225] | |||||||||||||

| 245. | Ganodeweberiol G | Significant | α | -glucosidase inhibitory activity (IC | 50 | = 165.9 µM) | G. weberianum | [77] |

Figure 3. Suggested mechanisms by which ganoderic acid DM (GA-DM) may inhibit prostate cancer cell proliferation and metastasis.

Figure 4

).

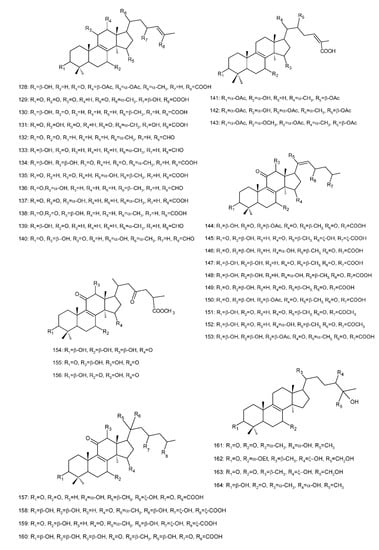

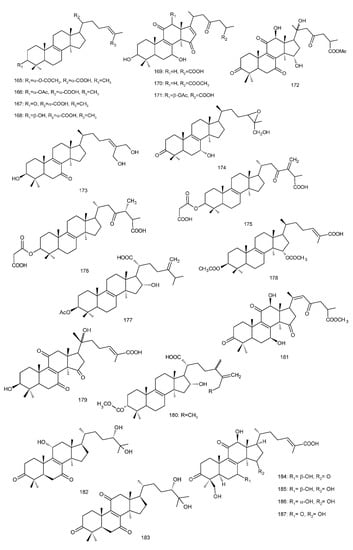

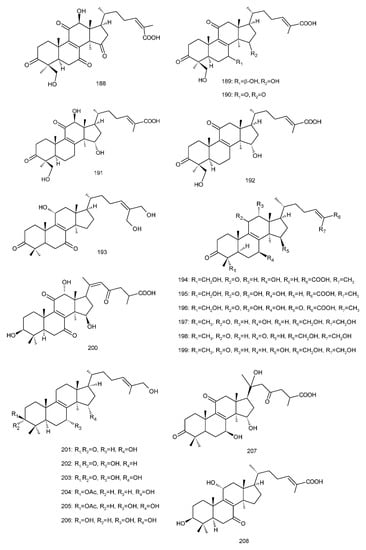

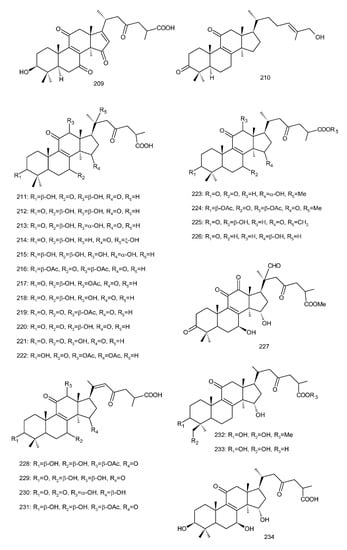

Figure 4. Chemical structures of several 8,9-double-bond triterpenoids (1–245).

References

- Karsten, P.A. Enumeratio boletinearum et poly-porearum fennicarum. Systemate novo dispositarum. Rev. Mycol. 1881, 3, 16–19.

- Upadhyay, M.; Shrivastava, B.; Jain, A.; Kidwai, M.; Kumar, S.; Gomes, J.; Goswami, D.G.; Panda, A.K.; Kuhad, R.C. Production of ganoderic acid by Ganoderma lucidum RCKB-2010 and its therapeutic potential. Ann. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 839–846.

- He, M.-Q.; Zhao, R.-L.; Hyde, K.D.; Begerow, D.; Kemler, M.; Yurkov, A.; McKenzie, E.H.; Raspé, O.; Kakishima, M.; Sánchez-Ramírez, S.; et al. Notes, outline and divergence times of basidiomycota. Fungal Divers. 2019, 99, 105–367.

- Badalyan, S.M.; Gharibyan, N.G.; Iotti, M.; Zambonelli, A. Morphological and ecological screening of different collections of medicinal white-rot bracket fungus Ganoderma adspersum (Schulzer) Donk (Agaricomycetes, Polyporales). Ital. J. Mycol. 2019, 48, 1–15.

- Gryzenhout, M.; Ghosh, S.; Tchotet Tchoumi, J.M.; Vermeulen, M.; Kinge, T.R. Ganoderma: Diversity, ecological significances, and potential applications in industry and allied sectors. In Industrially Important Fungi for Sustainable Development, Fungal Biology; Abdel-Azeem, A.M., Yadav, A.N., Yadav, N., Usmani, Z., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 295–334.

- Moncalvo, J.M.; Ryvarden, L. A Nomenclatural Study of the Ganodermataceae Donk, Synopsis Fungorum 11; Fungiflora: Oslo, Norway, 1997; pp. 1–114.

- Ryvarden, L.; Johansen, I. A Preliminary Polypore Flora of East Africa; Fungiflora: Oslo, Norway, 1980; pp. 1–636.

- Gilbertson, R.L.; Ryvarden, L. North American polypores. Abortiporus-Lindtneria; Fungiflora A/S: Oslo, Norway, 1986; Volume 1, pp. 1–433.

- Ryvarden, L.; Gilbertson, R.L. European Polypores 1, Synop Fungorum 6; Fungiflora A/S: Oslo, Norway, 1993; pp. 1–387.

- Quanten, E. The Polypores (Polyporaceae s.l.) of Papua New Guinea: A Preliminary Conspectus, Opera Botanica Belgica 11; National Botanic Garden of Belgium: Meise, Belgium, 1997; pp. 1–352.

- Nunez, M.; Ryvarden, L. East Asian Polypores 1. Ganodermataceae and Hymenochaetaceae, Synop Fungorum 13; Fungiflora A/S: Oslo, Norway, 2000; pp. 1–168.

- Welti, S.; Courtecuisse, R. The Ganodermataceae in the French West Indies (Guadeloupe and Martinique). Fungal Divers. 2010, 43, 103–126.

- Arenas, M.C.; Tadiosa, E.R.; Reyes, R.G. Taxonomic inventory based on physical distribution of macrofungi in Mt. Maculot, Cuenca, Batangas, Philippines. Int. J. Biol. Pharm. Allied Sci. 2018, 7, 672–687.

- Luangharn, T.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Dutta, A.K.; Paloi, S.; Promputtha, I.; Hyde, K.D.; Xu, J.; Mortimer, P.E. Ganoderma (Ganodermataceae, Basidiomycota) species from the Greater Mekong Subregion. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 819.

- Morera, G.; Lupo, S.; Alaniz, S.; Robledo, G. Diversity of the Ganoderma species in Uruguay. Neotrop. Biodivers. 2021, 7, 570–585.

- Runnel, K.; Miettinen, O.; Lõhmus, A. Polypore fungi as a flagship group to indicate changes in biodiversity—A test case from Estonia. IMA Fungus 2021, 12, 2.

- Ueitele, I.S.E.; Horn, L.N.; Kadhila, N.P. Ganoderma research activities and development in Namibia. AJOM 2021, 4, 29–39.

- He, J.; Han, X.; Luo, Z.-L.; Li, E.-X.; Tang, S.-M.; Luo, H.-M.; Niu, K.-Y.; Su, X.-J.; Li, S.-H. Species diversity of Ganoderma (Ganodermataceae, Polyporales) with three new species and a key to Ganoderma in Yunnan province, China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1035434.

- Ying, C.-C.; Wang, Y.-C.; Tang, H. Icones of Medicinal Fungi from China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1987; p. 575.

- Dai, Y.C.; Yang, Z.L.; Cui, B.K.; Yu, C.J.; Zhou, L.W. Species diversity and utilization of medicinal mushrooms and fungi in China (review). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2009, 3, 287–302.

- Wu, F.; Zhou, L.-W.; Yang, Z.-L.; Bau, T.; Li, T.-H.; Dai, Y.-C. Resource diversity of Chinese macrofungi: Edible, medicinal and poisonous species. Fungal Divers. 2019, 98, 1–76.

- El Sheikha, A.F.E. Nutritional profile and health benefits of Ganoderma lucidum “Lingzhi, Reishi, or Mannentake” as functional foods: Current scenario and future perspectives. Foods 2022, 11, 1030.

- Li, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yao, W.; Chen, R. Research status and progress of the triterpenoids in Ganoderma lucidum. Med. Plant 2012, 3, 75–81.

- Liu, H.; Guo, L.-J.; Li, S.-L.; Fan, L. Ganoderma shanxiense, a new species from northern China based on morphological and molecular evidence. Phytotaxa 2019, 406, 129–136.

- Li, L.F.; Liu, H.B.; Zhang, Q.W.; Li, Z.P.; Wong, T.L.; Fung, H.Y.; Zhang, J.X.; Bai, S.P.; Lu, A.P.; Han, Q.B. Comprehensive comparison of polysaccharides from Ganoderma lucidum and G. sinense: Chemical, anti-tumor, immunomodulating and gut-microbiota modulatory properties. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6172.

- Ngai, P.H.K.; Ng, T.B. A mushroom (Ganoderma capense) lectin with spectacular thermostability, potent mitogenic activity on splenocytes, and antiproliferative activity toward tumor cells. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Commun. 2004, 314, 988–993.

- Lee, S.; Shim, S.H.; Kim, J.S.; Shin, K.H.; Kang, S.S. Aldose reductase inhibitors from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma applanatum. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 1103–1105.

- Gurunathan, S.; Raman, J.; Malek, S.N.A.; John, P.A.; Vikineswary, S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ganoderma neo-japonicum Imazeki: A potential cytotoxic agent against breast cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 4399–4413.

- Wang, L.; Li, J.-Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.-M.; Liu, H.-G.; Wang, Y.-Z. Traditional uses, chemical components and pharmacological activities of the genus Ganoderma P. Karst: A review. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 42084–42097.

- Shankar, A.; Sharma, K.K. Fungal secondary metabolites in food and pharmaceuticals in the era of multiomics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 3465–3488.

- Chen, Y.; Lan, P. Total syntheses and biological evaluation of the Ganoderma lucidum alkaloids lucidimines B and C. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 3471–3481.

- Xia, Q.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Zhu, D.; Yang, G.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Mao, X.; et al. A comprehensive review of the structure elucidation and biological activity of triterpenoids from Ganoderma spp. Molecules 2014, 19, 17478–17535.

- Baby, S.; Johnson, A.J.; Govindan, B. Secondary metabolites from Ganoderma. Phytochemistry 2015, 114, 66–101.

- Wang, K.; Bao, L.; Xiong, W.; Ma, K.; Han, J.; Wang, W.; Yin, W.; Liu, H. Lanostane triterpenes from the Tibetan medicinal mushroom Ganoderma leucocontextum and their inhibitory effects on HMG-CoA reductase and α-glucosidase. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 1977–1989.

- Angulo-Sanchez, L.T.; López-Peña, D.; Torres-Moreno, H.; Gutiérrez, A.; Gaitán-Hernández, R.; Esquedaa, M. Biosynthesis, gene expression, and pharmacological properties of triterpenoids of Ganoderma species (Agaricomycetes): A review. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2022, 24, 1–17.

- Isaka, M.; Chinthanom, P.; Kongthong, S.; Srichomthong, K.; Choeyklin, R. Lanostane triterpenes from cultures of the basidiomycete Ganoderma orbiforme BCC 22324. Phytochemistry 2013, 87, 133–139.

- Martínez-Montemayor, M.M.; Ling, T.; Suárez-Arroyo, I.J.; Ortiz-Soto, G.; Santiago-Negrón, C.L.; Lacourt-Ventura, M.Y.; Valentín-Acevedo, A.; Lang, W.H.; Rivas, F. Identification of biologically active Ganoderma lucidum compounds and synthesis of improved derivatives that confer anti-cancer activities in vitro. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 115.

- Shim, S.H.; Ryu, J.; Kim, J.S.; Kang, S.S.; Xu, Y.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, S.; Shin, K.H. New lanostane-type triterpenoids from Ganoderma applanatum. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 1110–1113.

- Paterson, R.R. Ganoderma—A therapeutic fungal biofactory. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 1985–2001.

- Cilerdzic, J.; Vukojevic, J.; Stajic, M.; Stanojkovic, T.; Glamoclija, J. Biological activity of Ganoderma lucidum basidiocarps cultivated on alternative and commercial substrate. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 312–329.

- Peng, X.R.; Li, L.; Dong, J.R.; Lu, S.Y.; Lu, J.; Li, X.N.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, M.H. Lanostane-type triterpenoids from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma applanatum. Phytochemistry 2019, 157, 103–110.

- Shi, J.-X.; Chen, G.-Y.; Sun, Q.; Meng, S.-Y.; Chi, W.-Q. Antimicrobial lanostane triterpenoids from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma applanatum. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 157, 1001–1007.

- Muhsin, T.M.; Al-Duboon, A.-H.A.; Khalaf, K.T. Bioactive compounds from a polypore fungus Ganoderma applanatum (Pers. ex Wallr.) Pat. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 4, 205–212.

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; Nikšić, M.; Vrvić, M.M.; Todorović, N.; Jakovljević, D.; Van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Antioxidative activities and chemical characterization of polysaccharide extracts from the widely used mushrooms Ganoderma applanatum, Ganoderma lucidum, Lentinus edodes and Trametes versicolor. J. Food Compost. Anal. 2012, 26, 144–153.

- Al-Fatimi, M.; Wurster, M.; Kreisel, H.; Lindequist, U. Antimicrobial, cytotoxic and antioxidant activity of selected basidiomycetes from Yemen. Pharmazie 2005, 60, 776–780.

- Niedermeyer, T.H.; Lindequist, U.; Mentel, R.; Gordes, D.; Schmidt, E.; Thurow, K.; Lalk, M. Antiviral terpenoid constituents of Ganoderma pfeifferi. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1728–1731.

- Hsu, C.L.; Yu, Y.S.; Yen, G.C. Lucidenic acid B induces apoptosis in human leukemia cells via a mitochondria-mediated pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3973–3980.

- Smania, E.F.A.; Delle Monache, F.; Smania, A.; Yunes, R.A.; Cuneo, R.S. Antifungal activity of sterols and triterpenes isolated from Ganoderma annulare. Fitoterapia 2003, 74, 375–377.

- Rosecke, J.; Konig, W.A. Constituents of various wood-rotting basidiomycetes. Phytochemistry 2000, 54, 603–610.

- Li, L.; Peng, X.R.; Dong, J.R.; Lu, S.Y.; Li, X.N.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, M.H. Rearranged lanostane-type triterpenoids with anti-hepatic fibrosis activities from Ganoderma applanatum. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 31287–31295.

- Peng, X.-R.; Wang, Q.; Su, H.-G.; Zhou, L.; Xiong, W.-Y.; Qiu, M.-H. Anti-adipogenic lanostane-type triterpenoids from the edible and medicinal mushroom Ganoderma applanatum. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 331.

- Ma, K.; Ren, J.; Han, J.; Bao, L.; Li, L.; Yao, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhou, B.; Liu, H. Ganoboninketals A–C, antiplasmodial 3,4-seco-27-norlanostane triterpenes from Ganoderma boninense Pat. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 1847–1852.

- Huang, S.-Z.; Ma, Q.-Y.; Kong, F.-D.; Guo, Z.-K.; Cai, C.-H.; Hu, L.-L.; Zhou, L.-M.; Wang, Q.; Dai, H.-F.; Mei, W.-L.; et al. Lanostane-type triterpenoids from the fruiting body of Ganoderma calidophilum. Phytochemistry 2017, 143, 104–110.

- Li, N.; Yan, C.; Hua, D.; Zhang, D. Isolation, purification, and structural characterization of a novel polysaccharide from Ganoderma capense. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 57, 285–290.

- Keller, A.C.; Keller, J.; Maillard, M.P.; Hostettmann, K. A lanostane-type steroid from the fungus Ganoderma carnosum. Phytochemistry 1997, 46, 963–965.

- Peng, X.-R.; Liu, J.-Q.; Wan, L.-S.; Li, X.-N.; Yan, Y.-X.; Qiu, M.-H. Four new polycyclic meroterpenoids from Ganoderma cochlear. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 5262–5265.

- Peng, X.-R.; Liu, J.-Q.; Wang, C.-F.; Li, X.-Y.; Shu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, M.-H. Hepatoprotective effects of triterpenoids from Ganoderma cochlear. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 737–743.

- Yu, C.; Cao, C.Y.; Shi, P.D.; Yang, A.A.; Yang, Y.X.; Huang, D.S.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.M.; Gao, J.M.; Yin, X. Highly oxygenated chemical constitutes and rearranged derivatives with neurotrophic activity from Ganoderma cochlear. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 295, 115393.

- Chen, S.-Y.; Chang, C.-L.; Chen, T.-H.; Chang, Y.-W.; Lin, S.-B. Colossolactone H, a new Ganoderma triterpenoid exhibits cytotoxicity and potentiates drug efficacy of gefitinib in lung cancer. Fitoterapia 2016, 114, 81–91.

- Jo, W.-S.; Park, H.-N.; Cho, D.-H.; Yoo, Y.-B.; Park, S.-C. Detection of extracellular enzyme activities in Ganoderma neo-japonicum. Mycobiology 2011, 39, 118–120.

- Qiao, Y.; Zhang, X.-M.; Dong, X.-C.; Qiu, M.-H. A new 18(13 → 12β)-abeo-lanostadiene triterpenoid from Ganoderma fornicatum. Helv. Chim. Acta 2006, 89, 1038–1041.

- Peng, X.; Liu, J.; Xia, J.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Deng, Y.; Bao, N.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, M. Lanostane triterpenoids from Ganoderma hainanense J. D. Zhao. Phytochemistry 2015, 114, 137–145.

- Li, T.-H.; Hu, H.-P.; Deng, W.-Q.; Wu, S.-H.; Wang, D.-M.; Tsering, T. Ganoderma leucocontextum, a new member of the G. lucidum complex from southwestern China. Mycoscience 2015, 56, 81–85.

- Wei, J.-C.; Wang, Y.-X.; Dai, R.; Tian, X.-G.; Sun, C.-P.; Ma, X.-C.; Jia, J.-M.; Zhang, B.-J.; Huo, X.-K.; Wang, C. C27-Nor lanostane triterpenoids of the fungus Ganoderma lucidum and their inhibitory effects on acetylcholinesterase. Phytochem. Lett. 2017, 20, 263–268.

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zuo, J.; Gong, X.; Yi, F.; Zhu, W.; Li, L. Advances in research on the active constituents and physiological effects of Ganoderma lucidum. Biomed. Dermatol. 2019, 3, 6.

- Li, D.; Leng, Y.; Liao, Z.; Hu, J.; Sun, Y.; Deng, S.; Wang, C.; Tian, X.; Zhou, J.; Wang, R. Nor-triterpenoids from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma lucidum and their inhibitory activity against FAAH. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 158, 105161.

- Su, H.; Peng, X.; Shi, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, M. Lanostane triterpenoids with anti-inflammatory activities from Ganoderma lucidum. Phytochemistry 2020, 173, 112256.

- Hirotani, M.; Ino, C.; Hatano, A.; Takayanagi, H.; Furuya, T. Ganomastenols A, B, C and D, cadinene sesquiterpenes, from Ganoderma mastoporum. Phytochemistry 1995, 40, 161–165.

- Yangchum, A.; Fujii, R.; Choowong, W.; Rachtawee, P.; Pobkwamsuk, M.; Boonpratuang, T.; Mori, S.; Isaka, M. Lanostane triterpenoids from cultivated fruiting bodies of basidiomycete Ganoderma mbrekobenum. Phytochemistry 2022, 196, 113075.

- Chen, X.Q.; Chen, L.X.; Zhao, J.; Tang, Y.P.; Li, S.P. Nortriterpenoids from the fruiting bodies of the mushroom Ganoderma resinaceum. Molecules 2017, 22, 1073.

- Liu, C.; Zhao, F.; Chen, R. A novel alkaloid from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma sinense Zhao, Xu et Zhang. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2010, 21, 197–199.

- Liu, J.-Q.; Wang, C.-F.; Peng, X.-R.; Qiu, M.-H. New alkaloids from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma sinense. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2011, 1, 93–96.

- Da, J.; Wu, W.-Y.; Hou, J.-J.; Long, H.-L.; Yao, S.; Yang, Z.; Cai, L.-Y.; Yang, M.; Jiang, B.-H.; Liu, X.; et al. Comparison of two officinal Chinese pharmacopoeia species of Ganoderma based on chemical research with multiple technologies and chemometrics analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 1222, 59–70.

- Liu, L.-Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.-Q.; Kang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, R.-Y. Triterpenoids of Ganoderma theaecolum and their hepatoprotective activities. Fitoterapia 2014, 98, 254–259.

- Ma, Q.-Y.; Luo, Y.; Huang, S.-Z.; Guo, Z.-K.; Dai, H.-F.; Zhao, Y.-X. Lanostane triterpenoids with cytotoxic activities from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma hainanense. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 15, 1214–1219.

- Chien, R.-C.; Tsai, S.-Y.; Lai, E.Y.-C.; Mau, J.-L. Antiproliferative activities of hot water extracts from culinary-medicinal mushrooms, Ganoderma tsugae and Agrocybe cylindracea (Higher Basidiomycetes) on cancer cells. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2015, 17, 453–462.

- Yang, L.; Kong, D.-X.; Xiao, N.; Ma, Q.-Y.; Xie, Q.-Y.; Guo, J.-C.; Ying Deng, C.; Ma, H.-X.; Hua, Y.; Dai, H.-F.; et al. Antidiabetic lanostane triterpenoids from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma weberianum. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 127, 106025.

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Q.; Zhou, S.; Feng, J.; Chen, H. Polysaccharide of Ganoderma and its bioactivities. In Ganoderma and Health: Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Lin, Z., Yang, B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1181, pp. 107–134.

- Chan, J.S.; Asatiani, M.D.; Sharvit, L.E.; Trabelcy, B.; Barseghyan, G.S.; Wasser, S.P. Chemical composition and medicinal value of the new Ganoderma tsugae var. jannieae CBS-120304 medicinal higher basidiomycete mushroom. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2015, 17, 735–747.

- Ahmad, R.; Riaz, M.; Khan, A.; Aljamea, A.; Algheryafi, M.; Sewaket, D.; Alqathama, A. Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi) an edible mushroom; a comprehensive and critical review of its nutritional, cosmeceutical, mycochemical, pharmacological, clinical, and toxicological properties. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 6030–6062.

- Kolniak-Ostek, J.; Oszmianski, J.; Szyjka, A.; Moreira, H.; Barg, E. Anticancer and antioxidant activities in Ganoderma lucidum wild mushrooms in Poland, as well as their phenolic and triterpenoid compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9359.

- Bhat, Z.A.; Wani, A.H.; War, J.M.; Bhat, M.Y. Major bioactive properties of Ganoderma polysaccharides: A review. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2021, 14, 11–24.

- Gallo, A.L.; Soler, F.; Pellizas, C.; Vélez, M.L. Polysaccharide extracts from mycelia of Ganoderma australe: Effect on dendritic cell immunomodulation and antioxidant activity. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 3251–3262.

- Veena, R.K.; Janardhanan, K.K. Polysaccharide-protein complex isolated from fruiting bodies and cultured mycelia of Lingzhi or reishi medicinal mushroom, Ganoderma lucidum (agaricomycetes), attenuates doxorubicin-induced oxidative stress and myocardial injury in rats. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2022, 24, 31–40.

- Cragg, G.M.; Kingston, D.G.I.; Newman, D.J. Anticancer Agents from Natural Products, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 1–600.

- Mfopa, A.; Mediesse, F.K.; Mvongo, C.; Nkoubatchoundjwen, S.; Lum, A.A.; Sobngwi, E.; Kamgang, R.; Boudjeko, T. Antidyslipidemic potential of water-soluble polysaccharides of Ganoderma applanatum in MACAPOS-2-induced obese rats. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 2452057.

- Seweryn, E.; Ziała, A.; Gamian, A. Health-promoting of polysaccharides extracted from Ganoderma lucidum. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2725.

- Bleha, R.; Třešnáková, L.; Sushytskyi, L.; Capek, P.; Čopíková, J.; Klouček, P.; Jablonský, I.; Synytsya, A. Polysaccharides from basidiocarps of the polypore fungus Ganoderma resinaceum: Isolation and structure. Polymers 2022, 14, 255.

- Loyd, A.L.; Barnes, C.W.; Held, B.W.; Schink, M.J.; Smith, M.E.; Smith, J.A.; Blanchette, R.A. Elucidating “lucidum”: Distinguishing the diverse laccate Ganoderma species of the United States. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199738.

- Jargalmaa, S.; Eimes, J.A.; Park, M.S.; Park, J.Y.; Oh, S.-Y.; Lim, Y.W. Taxonomic evaluation of selected Ganoderma species and database sequence validation. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3596.

- Tchotet Tchoumi, J.M.; Coetzee, M.P.; Rajchenberg, M.; Roux, J. Taxonomy and species diversity of Ganoderma species in the Garden Route National Park of South Africa inferred from morphology and multilocus phylogenies. Mycologia 2019, 111, 730–747.

- Hou, D. A new species of Ganoderma from Taiwan. Quat. J. Taiwan Mus. 1950, 3, 101–105.

- Zhao, J.D.; Xu, L.W.; Zhang, X.Q. Taxonomic studies on the family Ganodermataceae of China II. Acta Mycol. Sin. 1983, 2, 159–167.

- Cao, Y.; Wu, S.H.; Dai, Y.C. Species clarification of the prize medicinal Ganoderma mushroom “Lingzhi”. Fungal Divers. 2012, 56, 49–62.

- Wu, G.-S.; Lu, J.J.; Guo, J.-J.; Li, Y.-B.; Tan, W.; Dang, Y.-Y.; Zhong, Z.-F.; Xu, Z.-T.; Chen, X.-P.; Wang, Y.-T. Ganoderic acid DM, a natural triterpenoid, induces DNA damage, G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 408–414.

- Patouillard, N.T. Le genre Ganoderma. Bull. Soc. Mycol. Fr. 1889, 5, 64–80.

- Murrill, W.A. The polyporaceae of North America. I. The genus Ganoderma. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 1902, 29, 599–608.

- Murrill, W.A. Polyporaceae. North American Flora; The New York Botanical Garden: New York, NY, USA, 1908; Volume 9, pp. 73–131.

- Zhou, L.-W.; Cao, Y.; Wu, S.-H.; Vlasák, J.; Li, D.-W.; Li, M.-J.; Dai, Y.-C. Global diversity of the Ganoderma lucidum complex (Ganodermataceae, Polyporales) inferred from morphology and multilocus phylogeny. Phytochemistry 2015, 114, 7–15.

- Du, Z.; Dong, C.-H.; Wang, K.; Yao, Y.-J. Classification, biological characteristics and cultivations of Ganoderma. In Ganoderma and Health: Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Lin, Z., Yang, B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1181, pp. 15–58.

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Z.; Pei, H.; Chen, Z.; Tan, X.; Hu, J.; Yang, B.; Sun, J. Intraspecific variation and phylogenetic relationships are revealed by ITS1 secondary structure analysis and single-nucleotide polymorphism in Ganoderma lucidum. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169042.

- Loyd, A.L.; Smith, J.A.; Richter, B.S.; Blanchette, R.A.; Smith, M.E. The laccate Ganoderma of the South-Eastern United States: A cosmopolitan and important genus of wood decay fungi. EDIS 2017, 2017, 6.

- Anonymous. Shen Nong Materia Medica; Beijing People’s Hygiene Press: Beijing, China, 1955.

- Moncalvo, J.M.; Wang, H.F.; Hseu, R.S. Gene phylogeny of the Ganoderma lucidum complex based on ribosomal DNA sequences. Comparison with traditional taxonomic characters. Mycol. Res. 1995, 99, 1489–1499.

- Hapuarachchi, K.K.; Wen, T.C.; Deng, C.Y.; Kang, J.C.; Hyde, K.D. Mycosphere Essays 1: Taxonomic confusion in the Ganoderma lucidum species complex. Mycosphere 2015, 6, 542–559.

- Haddow, W.R. Studies in Ganoderma. J. Arnold Arbor. 1931, 12, 25–46.

- Overholts, L.O. The Polyporaceae of the United States, Alaska and Canada; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1953; pp. 1–466.

- Steyaert, R.L. Basidiospores of two Ganoderma Species and others of two related genera under the scanning electron microscope. Kew Bull. 1977, 31, 437–442.

- Nobles, M.K. Identification of cultures of wood–inhabiting Hymenomycetes. Can. J. Bot. 1965, 43, 1097–1139.

- Wang, D.M.; Wu, S.H.; Su, C.H.; Peng, J.T.; Shih, Y.H. Ganoderma multipileum, the correct name for “G. lucidum” in tropical Asia. Bot. Stud. 2009, 50, 451–458.

- Wang, X.-C.; Xi, R.-J.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.-M.; Yao, Y.-J. The species identity of the widely cultivated Ganoderma, ‘G. lucidum’ (Ling-zhi), in China. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40857.

- Yang, L.Z.; Feng, B. What is the Chinese “Lingzhi”?—A taxonomic mini–review. Mycology 2013, 4, 1–4.

- Talapatra, S.K.; Talapatra, B. Triterpenes (C30). In Chemistry of Plant Natural Products: Stereochemistry, Conformation, Synthesis, Biology, and Medicine, 1st ed.; Talapatra, S.K., Talapatra, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 517–552.

- Wang, Q.; Cao, R.; Zhang, Y. Biosynthesis and regulation of terpenoids from basidiomycetes: Exploration of new research. AMB Expr. 2021, 11, 150.

- Yang, M.; Wang, X.; Guan, S.; Xia, J.; Sun, J.; Guo, H.; Guo, D.A. Analysis of triterpenoids in Ganoderma lucidum using liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectr. 2007, 18, 927–939.

- Lin, Y.-X.; Sun, J.-T.; Liao, Z.-Z.; Sun, Y.; Tian, X.-G.; Jin, L.-L.; Wang, C.; Leng, A.-J.; Zhou, J.; Li, D.-W. Triterpenoids from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma lucidum and their inhibitory activity against FAAH. Fitoterapia 2022, 158, 105161.

- Sappan, M.; Rachtawee, P.; Srichomthong, K.; Boonpratuang, T.; Choeyklin, R.; Feng, T.; Liu, J.-K.; Isaka, M. Ganoellipsic acids A–C, lanostane triterpenoids from artificially cultivated fruiting bodies of Ganoderma ellipsoideum. Phytochem. Lett. 2022, 49, 27–31.

- Hirotani, M.; Asaka, I.; Furuya, T. Investigation of the biosynthesis of 3α-hydroxy triterpenoids, ganoderic acids T and S, by application of a feeding experiment using acetate. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1990, 1, 2751–2754.

- Noushahi, H.A.; Khan, A.H.; Noushahi, U.F.; Hussain, M.; Javed, T.; Zafar, M.; Batool, M.; Ahmed, U.; Liu, K.; Harrison, M.T.; et al. Biosynthetic pathways of triterpenoids and strategies to improve their biosynthetic efficiency. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 97, 439–454.

- Vranová, E.; Coman, D.; Gruissem, W. Network analysis of the MVA and MEP pathways for isoprenoid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 665–700.

- McGarvey, D.J.; Croteau, R. Terpenoid metabolism. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1015–1026.

- Shi, L.; Ren, A.; Mu, D.; Zhao, M. Current progress in the study on biosynthesis and regulation of ganoderic acids. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2010, 88, 1243–1251.

- Liu, D.; Gong, J.; Dai, W.; Kang, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, H.M.; Liu, W.; Liu, L.; Ma, J.; Xia, Z.; et al. The genome of Ganoderma lucidum provides insights into triterpense biosynthesis and wood degradation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36146.

- Shang, C.-H.; Zhu, F.; Li, N.; Ou-Yang, X.; Shi, L.; Zhao, M.-W.; Li, Y.-X. Cloning and characterization of a gene encoding HMG-CoA reductase from Ganoderma lucidum and its functional identification in yeast. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2008, 72, 1333–1339.

- Ding, Y.-X.; Ou-Yang, X.; Shang, C.-H.; Ren, A.; Shi, L.; Li, Y.-X.; Zhao, M.-W. Molecular cloning, characterization, and differential expression of a farnesyl-diphosphate synthase gene from the basidiomycetous fungus Ganoderma lucidum. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2008, 72, 1571–1579.

- Zhao, M.-W.; Liang, W.-Q.; Zhang, D.-B.; Wang, N.; Wang, C.-G.; Pan, Y.-J. Cloning and characterization of Squalene Synthase (SQS) gene from Ganoderma lucidum. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 17, 1106–1112.

- Ye, L.; Liu, S.; Xie, F.; Zhao, L.; Wu, X. Enhanced production of polysaccharides and triterpenoids in Ganoderma lucidum fruit bodies on induction with signal transduction during the fruiting stage. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196287.

- Fei, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, D.H.; Xu, J.W. Increased production of ganoderic acids by overexpression of homologous farnesyl diphosphate synthase and kinetic modeling of ganoderic acid production in Ganoderma lucidum. Microb. Cell Fact. 2019, 18, 115.

- Shi, L.; Qin, L.; Xu, Y.; Ren, A.; Fang, X.; Mu, D.; Tan, Q.; Zhao, M. Molecular cloning, characterization, and function analysis of a mevalonate pyrophosphate decarboxylase gene from Ganoderma lucidum. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 6149–6159.

- Zhang, D.H.; Jiang, L.X.; Li, N.; Yu, X.; Zhao, P.; Li, T.; Xu, J.W. Overexpression of the squalene epoxidase gene alone and in combination with the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A gene increases ganoderic acid production in Ganoderma lingzhi. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 4683–4690.

- Zhang, D.H.; Li, N.; Yu, X.Y.; Zhao, P.; Li, T.; Xu, J.W. Overexpression of the homologous lanosterol synthase gene in ganoderic acid biosynthesis in Ganoderma lingzhi. Phytochemistry 2017, 134, 46–53.

- Howes, M.R. Phytochemicals as anti-inflammatory nutraceuticals and phytopharmaceuticals. In Immunity and Inflammation in Health and Disease: Emerging Roles of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods in Immune Support; Chatterjee, S., Jungraithmayr, W., Bagchi, D., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 363–388.

- Ludwiczuk, A.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Georgiev, M. Terpenoids. In Pharmacognosy: Fundamentals, Applications and Strategies, 1st ed.; Badal, S., Delgoda, R., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 233–266.

- Muffler, K.; Leipold, D.; Scheller, M.C.; Haas, C.; Steingroewer, J.; Bley, T.; Neuhaus, H.E.; Mirata, M.A.; Schrader, J.; Ulber, R. Biotransformation of triterpenes. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 1–15.

- Blundell, R.; Azzopardi, J.; Briffa, J.; Rasul, A.; Vargas-de la Cruz, C.; Shah, M.A. Analysis of pentaterpenoids. In Recent Advances in Natural Products Analysis, 1st ed.; Nabavi, S.M., Saeedi, M., Nabavi, S.F., Silva, A.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 457–475.

- Gong, T.; Yan, R.; Kang, J.; Chen, R. Chemical components of Ganoderma. In Ganoderma and Health: Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Lin, Z., Yang, B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1181, pp. 59–106.

- Chen, R.; Kang, J. Quantitative analysis of components in Ganoderma. In Ganoderma and Health: Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Lin, Z., Yang, B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1181, pp. 135–155.

- Du, Q.; Cao, Y.; Liu, C. Lingzhi; an overview. In The Lingzhi Mushroom Genome. Compendium of Plant Genomes, 1st ed.; Liu, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–25.

- Ma, B.; Ren, W.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, J.; Ruan, Y.; Wen, C.N. Triterpenoids from the spores of Ganoderma lucidum. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2011, 3, 495–498.

- Liu, R.-M.; Li, Y.-B.; Liang, X.-F.; Liu, H.-Z.; Xiao, J.-H.; Zhong, J.-J. Structurally related ganoderic acids induce apoptosis in human cervical cancer HeLa cells: Involvement of oxidative stress and antioxidant protective system. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 240, 134–144.

- Yang, S.-X.; Yu, Z.-C.; Lu, Q.-Q.; Shi, W.-Q.; Laatsch, H.; Gao, J.-M. Toxic lanostane triterpenes from the basidiomycete Ganoderma amboinense. Phytochem. Lett. 2012, 5, 576–580.

- Lee, I.S.; Ahn, B.R.; Choi, J.S.; Hattori, M.; Min, B.S.; Bae, K.H. Selective cholinesterase inhibition by lanostane triterpenes from fruiting bodies of Ganoderma lucidum. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 6603–6607.

- Liu, J.; Kurashiki, K.; Shimizu, K.; Kondo, R. 5α-Reductase inhibitory effect of triterpenoids isolated from Ganoderma lucidum. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 29, 392–395.

- Liu, J.; Kurashiki, K.; Shimizu, K.; Kondo, R. Structure-activity relationship for inhibition of alpha-reductase by triterpenoids isolated from Ganoderma lucidum. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 8654–8660.

- Liu, J.; Shiono, J.; Shimizu, K.; Kukita, A.; Kukita, T.; Kondo, R. Ganoderic acid DM: Anti-androgenic osteoclastogenesis inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2154–2157.

- Liu, J.; Shiono, J.; Tsuji, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Kondo, R. Methyl ganoderic acid DM: A selective potent osteoclastogenesis inhibitor. Open Bioact. Compd. J. 2009, 2, 37–42.

- Miyamoto, I.; Liu, J.; Shimizu, K.; Sato, M.; Kukita, A.; Kukita, T.; Kondo, R. Regulation of osteoclastogenesis by ganoderic acid DM isolated from Ganoderma lucidum. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 602, 1–7.

- Chen, D.-H.; Chen, W.K.-D. Determination of ganoderic acids in triterpenoid constituents of Ganoderma tsugae. J. Food Drug Anal. 2003, 11, 195–201.

- Kubota, T.; Asaka, Y.; Miura, I.; Mori, H. Structures of ganoderic acid A and B, two new lanostane type bitter triterpenes from Ganoderma lucidum (FR.) Karst. Helv. Chim. Acta 1982, 65, 611–619.

- Yao, X.; Li, G.; Xu, H.; Lu, C. Inhibition of the JAK-STAT3 signaling pathway by ganoderic acid A enhances chemosensitivity of HepG2 cells to cisplatin. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 1740–1748.

- El-Mekkawy, S.; Meselhy, M.R.; Nakamura, N.; Tezuka, Y.; Hattori, M.; Kakiuchi, N.; Shimotohno, K.; Kawahata, T.; Otake, T. Anti-HIV-1 and anti-HIV-1-protease substances from Ganoderma lucidum. Phytochemistry 1998, 49, 1651–1657.

- Liu, C.; Yang, N.; Folder, W.; Cohn, J.; Wang, R.; Li, X. Ganoderic acid C isolated from Ganoderma lucidum suppress Lps-induced macrophage Tnf-α production by down-regulating Mapk, Nf-kappab and Ap-1 signaling pathways. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, AB127.

- Kikuchi, T.; Matsuda, S.; Kadota, S.; Ogita, Z. Ganoderic acid G and I and ganolucidic acid A and B, new triterpenoids from Ganoderma lucidum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1985, 33, 2628–2631.

- Koyama, K.; Imaizumi, T.; Akiba, M.; Kinoshita, K.; Takahashi, K.; Suzuki, A.; Yano, S.; Horie, S.; Watanabe, K.; Naoi, Y. Antinociceptive components of Ganoderma lucidum. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 224–227.

- Ruan, W.; Lim, A.H.H.; Huang, L.G.; Popovich, D.G. Extraction optimisation and isolation of triterpenoids from Ganoderma lucidum and their effect on human carcinoma cell growth. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 2264–2272.

- Hennicke, F.; Cheikh-Ali, Z.; Liebisch, T.; Maciá-Vicente, J.G.; Bode, H.B.; Piepenbring, M. Distinguishing commercially grown Ganoderma lucidum from Ganoderma lingzhi from Europe and East Asia on the basis of morphology, molecular phylogeny, and triterpenic acid profiles. Phytochemistry 2016, 127, 29–37.

- Kikuchi, T.; Kanomi, S.; Murai, Y.; Kadota, S.; Tsubono, K.; Ogita, Z.I. Constituents of the fungus Ganoderma lucidum (FR.) Karst. III. Structures of ganolucidic acids A and B, new lanostane-type triterpenoids. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1986, 34, 4030–4036.

- Nishitoba, T.; Sato, H.; Sakamura, S. Triterpenoids from the fungus Ganoderma lucidum. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 1777–1784.

- Li, Y.-Y.; Mi, Z.-Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, D.-S.; Tang, Y.-J. Lanostanoids isolated from Ganoderma lucidum mycelium cultured by submerged fermentation. Helv. Chim. Acta 2009, 92, 1586–1593.

- Komoda, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Ishihara, S.; Uchida, M.; Kohda, H.; Yamasaki, K. Structures of new terpenoid constituents of Ganoderma lucidum (Fr.) Karst (Polyporaceae). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1985, 33, 4829–4835.

- Wang, F.; Liu, J.K. Highly oxygenated lanostane triterpenoids from the fungus Ganoderma applanatum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 56, 1035–1037.

- Yue, Q.-X.; Song, X.-Y.; Ma, C.; Feng, L.-X.; Guan, S.-H.; Wu, W.-Y.; Yang, M.; Jiang, B.-H.; Liu, X.; Cui, Y.-J.; et al. Effects of triterpenes from Ganoderma lucidum on protein expression profile of HeLa cells. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 606–613.

- Wu, T.-S.; Shi, L.-S.; Kuo, S.-C. Cytotoxicity of Ganoderma lucidum triterpenes. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1121–1122.

- Fatmawati, S.; Shimizu, K.; Kondo, R. Ganoderic acid Df, a new triterpenoid with aldose reductase inhibitory activity from the fruiting body of Ganoderma lucidum. Fitoterapia 2010, 81, 1033–1036.