Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Ana Elena Rodriguez-Rodriguez and Version 3 by Jason Zhu.

The combination of insulin resistance and β-cells dysfunction leads to the onset of type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). This process can last for decades, as β-cells are able to compensate the demand for insulin and maintain normoglycemia. Understanding the adaptive capacity of β-cells during this process and the causes of its failure is essential to the limit onset of diabetes.

- pancreatic β-cells

- diabetes mellitus type 2

- post-transplant diabetes mellitus

- tacrolimus

- pathways

1. Introduction

Post-transplant diabetes mellitus (PTDM) affects 20–30% of the patients with a renal transplant [1]. The prevalence, incidence, evolution and consequences of PTDM have been recently reviewed [1]. Diverse risk factors for PTDM have been analysed and described [2]. Clearly, immunosuppressive medications used to avoid organ rejection are the main factor that induces diabetes. Other risk factors for PTDM are obesity, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and hypertriglyceridemia [3]. Of note, these factors have been also associated with the incidence of type 2 diabetes in the general population [4]. AOur group found that tacrolimus was particularly toxic to β-cells in patients with metabolic syndrome [5]. This was later confirmed in animal models of diabetes induced by TAC [6]. This information led to the hypothesis that TAC may accelerate the same damage in β-cells already induced by insulin resistance and obesity and so help explaining the pathogenesis of diabetes in the general population. Animal and cellular models of glucolipotoxicity seemed to confirm this idea [6][7][6,7]. So, understanding tacrolimus-induced β-cells toxicity may help improve theour knowledge not only of the pathogenesis of PTDM but also that of type 2 diabetes. In the present review we evaluate common pathways involved in β-cells dysfunction in T2DM and tacrolimus-induced PTDM.

2. Physiology of Pancreatic Islets

The pancreatic islets, also called Islets of Langerhans in honour of their discoverer Paul Langerhans in 1869, are irregular structures of about 100–200 μm, formed by accumulations of endocrine cells dispersed among the exocrine acini of the pancreatic tissue [8]. Islets only represent 1–2% of the pancreas and are highly vascularized mini organs receiving five times more blood than the adjacent exocrine tissue [8]. The cytoarchitecture of the islets is complex and varies between species. Islets contain basically four main types of cells. The most abundant are β-cells (50–80%), which secrete insulin, followed by alpha-cells (~20%) that secrete glucagon and PP-cells (10–35%), which secrete pancreatic polypeptide. Delta-cells (~5%) synthetize somatostatin and epsilon cells produce ghrelin and are less frequent [9].

3. Pancreatic β-Cell

The β-cell plays a central role in maintaining glucose homeostasis by the production and secretion of insulin. This hormone is a peptide with many diverse functions, including the promotion of glucose and amino acid uptake, glycogen synthase activity, protein metabolism, cell division and growth, as well as decreases lipolysis among the most important [10]. Structurally, insulin has two chains of polypeptides: chain A: 21 amino acids (a.a.), and chain B: 30 a.a., linked by two disulphide bridges. Insulin is synthesized as a precursor, proinsulin, which has a single polypeptide chain made up of the A and B chains and the C-peptide, which joins both chains [11]. The passage from proinsulin to insulin takes place in the trans-Golgi network and needs the breaking of the bonds between the C-peptide and both chains A and, B. Insulin and C-peptide are stored in secretory granules that also contain proteolytic enzymes (convertases), carboxypeptidases, C-peptide, and high concentrations of Ca2+. Murine β-cells can have more than 13,000 secretory granules of insulin and each granule may store more than 200,000 insulin molecules [12][13][12,13]. The production and release of insulin are highly regulated. The short-term regulation occurs at the release of insulin from granules. Long-term adaptation to glycaemic changes implies the regulation and changes of diverse processes like the transcription of insulin gene, translation of insulin mRNA, processing proinsulin into insulin and stimulation of insulin secretion [12]. The transcriptional regulation of insulin gene involves a sequence of elements within the promoter region of the gene, named, A.; C, E, Z and CRE elements. These are binding sites for important transcription factors that regulate insulin gene expression, such as: v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family, protein A (MafA), pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX-1) and β-2/Neurogenic differentiation 1 (NeuroD1) [12].

3.1. Mechanisms of Insulin Secretion

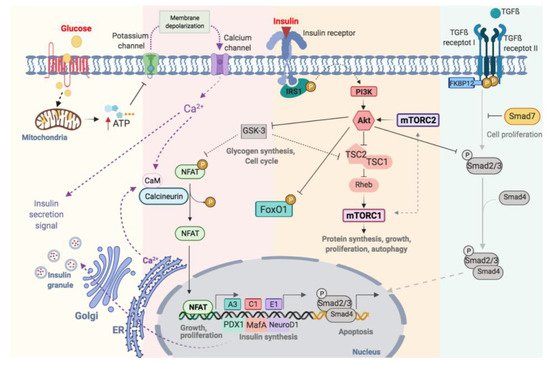

Glucose is the main stimulator of insulin secretion in β-cells [14]. When extracellular glucose increases, glucose is transported inside β-cells by the glucose transporter (GLUT2) (Figure 1). Once in the cytoplasm, glucose is phosphorylated by glucokinase (GCK) resulting in the formation of glucose-6-phosphate, which is incorporated into the Krebs cycle in the mitochondria increasing cytosolic ATP/ADP ratio (Figure 1). When the β-cell is at rest, the membrane potential remains stable at −70 mV, thanks to the constant flux of K+ through ATP-sensitive K+-channels (KATP-channels). These channels have two subunits: the pore, Kir6.2, and the regulatory subunit, SUR1 (sulfonylurea receptors) and both assembled with a 4:4 stoichiometry. The increase in ATP, caused by glucose metabolism, favours the closure of KATP-channels. The reduction of K+ conductance leads to the depolarization of the cytoplasmic membrane and the opening of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs), which promotes the entry of Ca2+ into the cell. This increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration is essential to trigger the fusion of the insulin-containing granules with the membrane and subsequent release of the insulin [15] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of functional regulation on pancreatic β-cell.

3.2. Functional Regulation of β-Cell

Optimal glycaemic control depends on changes in the production and secretion of insulin, as well as the regulation of β-cell proliferation. This process is highly complex and involves many factors, including membrane receptors, intracellular enzymes and proteins, grow factors and hormones (Figure 1). These factors are highly interrelated with a major degree of complexity. Consequently, its understanding requires both comprehensive and simplified approaches. TWe will describe the most relevant pathways involved in β-cell regulation will be described.

3.2.1. Calcineurin-NFAT Pathway

The increase in intracellular calcium, as a consequence of glucose metabolism, causes the activation of calcineurin, a cytoplasmic calcium-calmodulin-dependent serine/threonine phosphatase, which is responsible for dephosphorylating and translocating NFAT to the nucleus [16] (Figure 1). NFATs are a family of transcription factors that regulate cell proliferation and functional maintenance. Heit et al., demonstrated that the calcineurin-NFAT pathway is important for the maintenance and viability of β-cell. Calcineurin-knockout mice exhibited severe hyperglycaemia with increasing age as well as dysregulation of specific genes like insulin and others implicated in the maintenance of β-cell mass [17]. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) is a serine/threonine kinase implicated in the regulation of glycogen synthesis, protein synthesis and gene transcription [18]. GSK3 regulates NFAT pathway preventing its translocation to the nucleus [19] (Figure 1).

3.2.2. Insulin Receptor-IRS1-PI3K-AKT Pathway

Insulin acts in an autocrine manner promoting β-cell proliferation [20] by the phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and activation of phosphoinositol-3 kinase (PI3K). This activates Akt, an important serine/threonine kinase involved in multiple processes like the regulation of glucose and insulin metabolism, apoptosis, proliferation and, transcription or cell migration [21] (Figure 1). Fatrai et al. demonstrated that Akt is able to regulate key proteins of the β-cell cycle such as cyclin D1, D2, p21 and increase the activity of cyclin depended kinase-4 (Cdk4) in order to promote β-cell proliferation [22]. The constitutive expression of Akt in β-cells resulted in an increase in cell mass accompanied by hyperinsulinemia [23]. PI3K/Akt phosphorylates several proteins involves in different processes such as proliferation, cell growth, differentiation and survival (Figure 1). Akt phosphorylates the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC1/TSC2) inhibiting its GTPase activity allowing Rheb actives mTOR [24]. Thus, Akt and mTOR are closely related. mTOR can be part of two complexes: the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and 2 (mTORC2). For the complete activation of Akt, mTORC2 phosphorylates Akt in Ser-473 [24]. Akt regulates the cell cycle through the phosphorylation and inhibition of GSK3. The latter is related to the mTORC1 pathway by phosphorylating and inhibiting TSC2 [25][26][25,26]. Thus, the activation of Akt, via insulin, inactivates GSK3 and stimulates proliferation via mTORC1 (Figure 1). Also, Akt binds to the transcription factor Smad3 and prevents its binding to Smad4 and translocation to the nucleus for apoptosis induction (Figure 1) [27].

3.2.3. mTOR Pathway

mTOR is a key serine/threonine kinase that controls multiplex cellular processes in response to a variety of environmental stimuli including amino acids, glucose and oxidative stress [28][29][28,29] (Figure 1). As we commented above, mTOR is a protein can be part of two different complex: mTORC1 and mTORC2 [24]. The mTORC1 phosphorylates S6 kinase (S6K) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein-1 (4EBP1) [29]. The activation of this pathway stimulates ribosomal biogenesis and mRNA translation promoting the biosynthesis of protein. mTORC1 also regulates lipid biosynthesis by activating the major lipogenic regulator transcription factor SREBP1, which controls the expression of numerous genes involved in fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis [30].

3.2.4. Nuclear Factors Relevant in β-Cells Metabolism: PDX1, MafA, NeuroD and FoxO1

PDX-1 is considered the main transcription factor involved in the early development of the pancreas, β-cells differentiation and maintenance of β-cells mass. PDX-1 regulates transcription of genes such as insulin, GLUT2, glucokinase, NKx6.1 and MafA, among others [31][32][33][31,32,33]. Mice with a selective disruption of the Pdx1 gene in β-cells develop diabetes associated with a reduction in insulin production and GLUT2 expression. Mice heterozygous for Pdx1 develop glucose intolerance, increased apoptosis, decreased mass and abnormal islet architecture. This indicated that PDX-1 is crucial for maintaining the regulation of glucose metabolism [33]. In humans, mutations in this gene cause a monogenic form of type 2 diabetes, known as MODY 4 (maturity -onset diabetes of the young 4) [34].

MafA is a critical transcription factor for the maintenance of mature β cells [35]. It is only expressed in β-cells and acts as a potent activator of the insulin gene. Knockout mice for MafA develop glucose intolerance and diabetes, lower expression of the insulin gene, PDX-1, NeuroD and GLUT2 [36][37][38][36,37,38].

NeuroD1 is involved in pancreatic development and endocrine cell differentiation. It is expressed in mature β cells and, together with PDX1 and MafA, binds directly to the promoter of the insulin gene and controls its transcription [39].

Forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1) is an important transcription factor with a central role in multiple processes such as differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, cellular metabolism and response to cellular stress [40][41][42][43][44][40,41,42,43,44]. In β-cells, FoxO1 is a key transcription factor in the regulation of insulin and glucose homeostasis in response to stress. It is interesting to note that the levels of mRNA-foxo1 are higher in diabetic patients [45]. The activation of Akt via PI3K leads to the nuclear exclusion of FoxO1 (Figure 1) [46]. FoxO1 also regulates the expression of PDX-1 by two possible mechanisms: (1) the control the subcellular localization of PDX1, presenting an exclusive pattern within the nucleus, and (2) repressing the expression of FOXA2 (forkhead box protein A2), which in turn controls the promoter of Pdx1 [47]. Therefore, the regulation of PDX-1, MafA, NeuroD and FoxO1 is key to maintaining the functionality of β-cells [40].

3.2.5. TGF-β Receptor Pathway

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily includes TGF-β, activins and BMPs (bone morphogenetic proteins) regulates multiple cellular processes like proliferation, diffentiacion and apoptosis [48]. The activation of this pathway requires the phosphorylation of Type II and I transmembrane protein serine/threonine kinases receptors (TβR-II and TβR-I). Then, TβR-I phosphorylates Smad2 and Smad3 (R-Smads) and forms a complex with Smad4 (Co-Smads). The complex translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and regulates the transcription of genes. In β-cells, the activation of TGF-β/Smad3 represses insulin transcription reducing insulin content and secretion. Also, reduces the expression of the majority genes involved in β-cells function such as SUR1, FoxO1, Ins-1, Ki6.2, PDX-1, NeuroD, Nkx6.1 [49]. The inmunophilin FKBP12 binds to TβR-I and inhibits its phosphorylation by TβR-II, preventing the uncontrolled activation of TGFβ receptor [50][51][50,51]. The inhibitory Smads (I-Smad), like Smad7, negatively regulates the TGFβ pathway by the ubiquitination and degradation of TβRs and R-Smads or a simple disruptor of interactions between R-Smads and Co-Smads or TβRs and R-Smads [52] (Figure 1).