Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Jag Bhawan and Version 3 by Conner Chen.

Neurofibroma (NF) is defined as a histologically benign (WHO grade I) peripheral nerve sheath tumor composed of cells of diverse lineage including Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineurial cells, mast cells and macrophages with intermixed axons. The most common type of cutaneous neurofibroma (cNF) is the classic cNF. Variations in the cytomorphology and stromal characteristics in classic cNF give rise to different histopathological subtypes.

- cutaneous neurofibroma

- histopathological variants

- classification

1. Introduction

Neurofibroma has been a subject of intense medical curiosity from ancient Egypt until the present date. Before the word ‘neurofibroma’ was introduced, in the late 1700s and early 1880s, the term ‘cutaneous fibromas’ and ‘neuromas’ were used to describe skin tumors and deep nerve tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis, respectively. Although several researchers have made remarkable contributions to the understanding of this disease, Von Recklinghausen is credited with discovering the pathogenesis of these tumors. The nature of the neoplastic tissue in both types of tumor was described to be almost identical and result from the mingling of neural elements and connective tissue cells, thus giving birth to the term ‘neurofibroma’ [1][2][3][1,2,3].

Neurofibroma (NF) is defined as a histologically benign (WHO grade I) peripheral nerve sheath tumor composed of cells of diverse lineage including Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineurial cells, mast cells and macrophages with intermixed axons [4]. It is conjectured that Schwann cells constitute the neoplastic component, and the other cells are either present at the start or recruited eventually into the lesion. However, to date, the definitive cell of origin of NF remains ambiguous. Historically, Von Recklinghausen believed these tumors were of mesenchymal origin. It was not until 2002 that Schwann cells were undoubtedly shown to be the origin of NF. Current models indicate that different types of NF arise from a common cell of origin arising from a subpopulation of migrating neural crest stem cells (NCSCs) [5].

NF can occur sporadically or in association with genetic syndromes such as neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Several efforts have been made to classify NF based on their clinical appearance and histologic features, leading to multiple classification systems being published in the literature and some unpublished systems presented at the European NF meeting (2008) by Ortonne et al. [6]. The basic theme proposed in these systems involved classifying NF based on its anatomic location, growth pattern, and relationship to nerve and pathogenesis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of neurofibroma.

| Anatomic location | Cutaneous Cutaneous/subcutaneous Deep |

| Growth Pattern | Localized Diffuse/infiltrating |

| Relationship to nerve | Intraneural Extraneural |

| Pathogenesis | Endoneurial Perineurial Epineurial |

Cutaneous NF (cNF) can be further categorized as localized or diffuse. The localized variant is the most common, usually presenting in adulthood as an asymptomatic solitary polypoid or nodular lesion arising anywhere in the body without particular anatomic distribution and is rarely associated with NF1. However, the presence of multiple such lesions raises concerns regarding NF1. Diffuse cutaneous neurofibroma is an uncommon and clinically distinctive variant that usually presents in young adults as an ill-defined plaque of dermal and subcutaneous thickening with overlying hyperpigmentation, commonly on the head and neck or trunk. Approximately 10% of cases are associated with NF1. Localized and diffuse cNF rarely progress to malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) [4].

In patients with NF1, emphasis has been placed on distinguishing cNF, which is limited to dermis from the extension of deep NF into the skin, especially in cases demonstrating atypical features such as cytological atypia or increased cellularity. It is believed that the atypical changes in cNF represent reactive or degenerative changes while similar changes in a deep NF can be a manifestation of malignant transformation [6].

NFs, irrespective of their location, share common histologic and immunohistochemical features. However, unusual histologic features have been described in the literature occasionally, some of which have posed difficulty in its diagnosis as well as in differentiating it from other tumors. Megahed outlined ten different histopathological variants of NF [7]. Since then, over the years, many individual case reports elucidating peculiar histologic findings in cNF have been added to the literature.

2. Conventional/Classic cNF

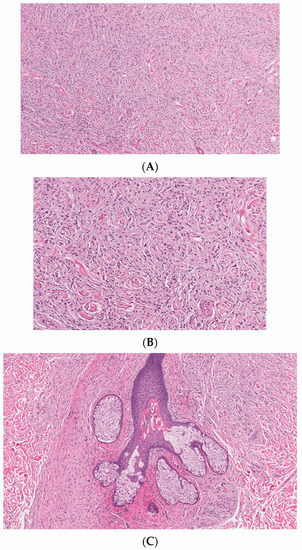

Classic localized cNF is a circumscribed unencapsulated tumor usually located in the dermis, often with extension into the subcutis. It is primarily comprises only endoneurial components, specifically lacking both an intact perineurium and intact epineurium [8]. It is composed of proliferations of multiple cell types in a variably collagenous and myxoid stroma. Besides Schwann cells, which are the predominant cell type, it contains perineurial-like cells, fibroblasts, endoneurial fibroblasts, mast cells, macrophages, endothelial cells and pericytes with scattered, intermingled axons (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Conventional cNF. (A) The lesion is made of scattered spindle cells that correspond to Schwann cells, fibroblasts and mast cells admixed numerous capillaries (Hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) stain, 50×) (B) (H&E, 100×). (C) Lesional cells surrounding the pilosebaceous unit (H&E, 40×).

Table 2.

Histopathological variants of Cutaneous Neurofibroma.

| Conventional/Classic cNF | ||

|---|---|---|

| According to variations in cell morphology: |

| |

| According to the variations in stroma: |

|