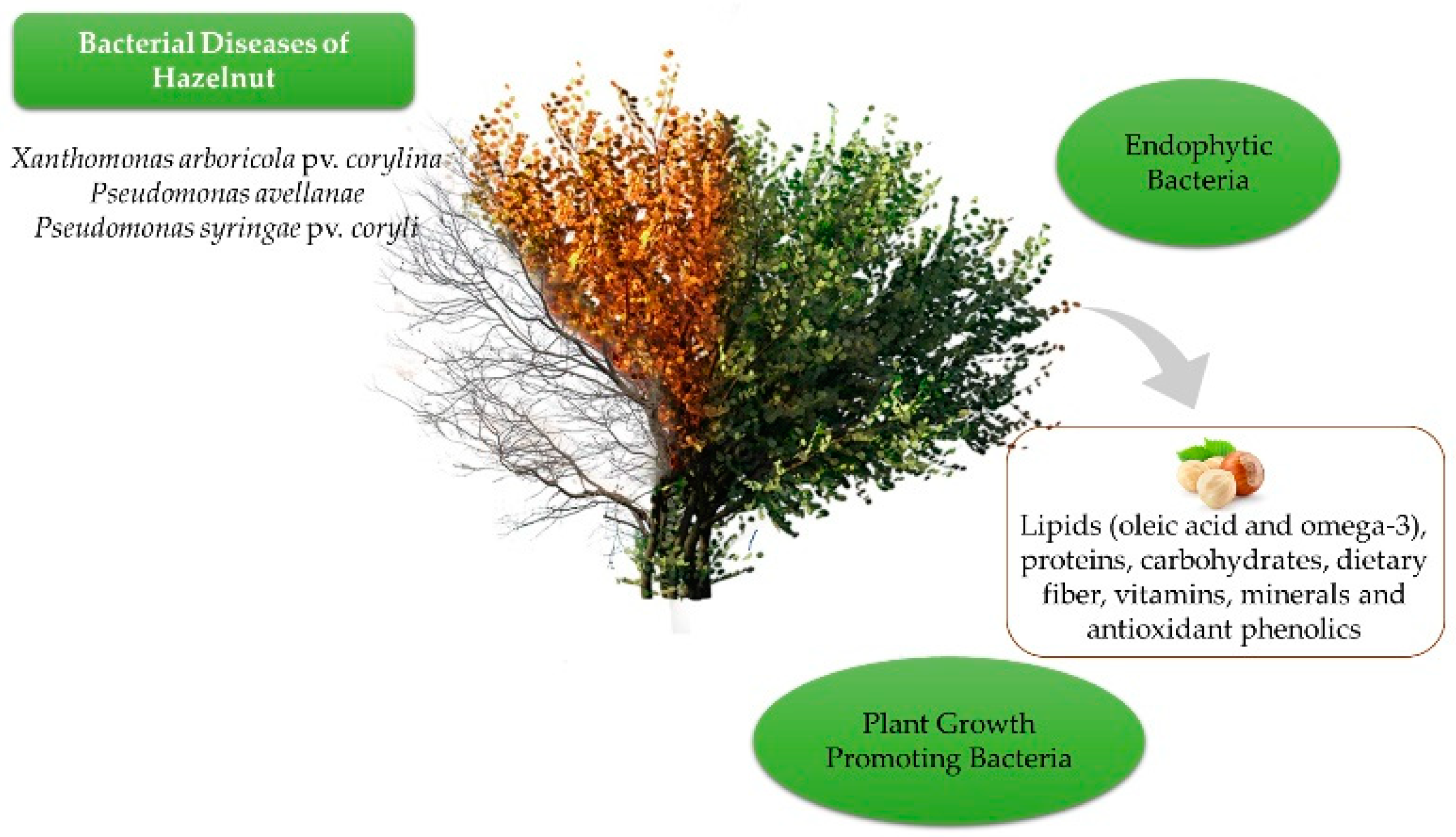

The cultivation of hazelnut (Corylus avellana) has expanded in several areas of Europe, Asia, Africa, and North and South America following the increased demand for raw materials by the food industry. Bacterial diseases caused by Xanthomonas arboricola pv. corylina and Pseudomonas avellanae are threats of major concern for hazelnut farmers. These pathogens have been controlled with copper-based products, which are being phased out in the European Union. Following the need for alternative practices to manage these diseases, some progress has been achieved through the exploitation of the plant’s systemic acquired resistance mechanisms, nanoparticle technology, as well as preventive measures based on hot water treatment of the propagation material.

- nut crops

- bacterial diseases

- endophytic microorganisms

- plant growth promoting bacteria

- sustainable disease management

1. Introduction

2. Bacterial Diseases of Hazelnut

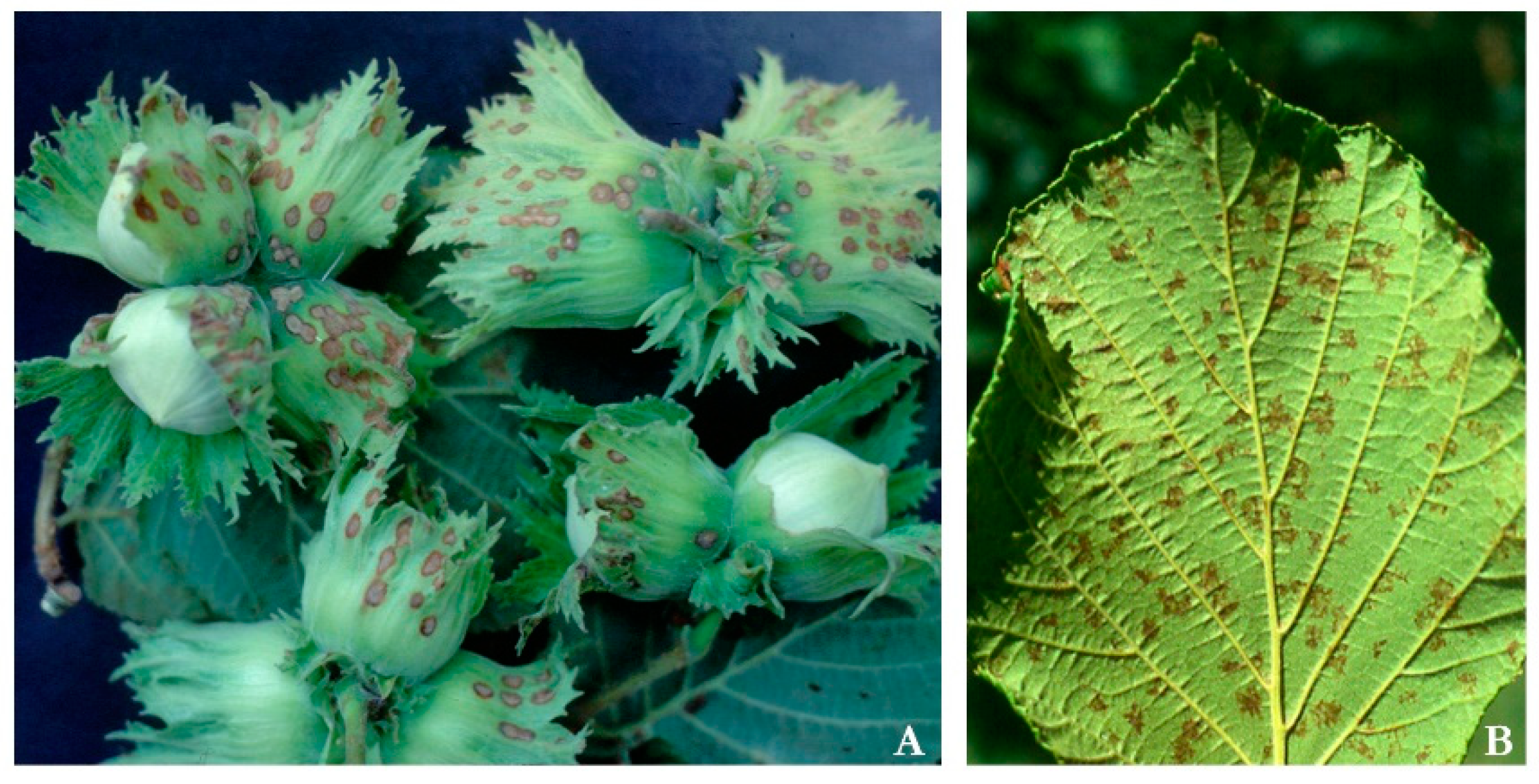

2.1. Bacterial Blight

2.2. Bacterial Canker

2.3. Other Bacterial Pathogens

3. Management of Bacterial Diseases of Hazelnut

References

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture-Statistical Yearbook; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 366.

- Silvestri, C.; Bacchetta, L.; Bellincontro, A.; Cristofori, V. Advances in cultivar choice, hazelnut orchard management, and nut storage to enhance product quality and safety: An overview. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 27–43.

- Alasalvar, C.; Shahidi, F.; Liyanapathirana, C.M.; Ohshima, T. Turkish tombul hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.). 1. Compositional characteristics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3790–3796.

- Köksal, A.İ.; Artik, N.; Şimşek, A.; Güneş, N. Nutrient composition of hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) varieties cultivated in Turkey. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 509–515.

- Jakopic, J.; Petkovsek, M.M.; Likozar, A.; Solar, A.; Stampar, F.; Veberic, R. HPLC–MS identification of phenols in hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) kernels. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1100–1106.

- Shahidi, F.; Alasalvar, C.; Liyana-Pathirana, C.M. Antioxidant phytochemicals in hazelnut kernel (Corylus avellana L.) and hazelnut byproducts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1212–1220.

- Pelvan, E.; Alasalvar, C.; Uzman, S. Effects of roasting on the antioxidant status and phenolic profiles of commercial Turkish hazelnut varieties (Corylus avellana L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 1218–1223.

- Cristofori, V.; Ferramondo, S.; Bertazza, G.; Bignami, C. Nut and kernel traits and chemical composition of hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) cultivars. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 88, 1091–1098.

- Bacchetta, L.; Aramini, M.; Zini, A.; Di Giammatteo, V.; Spera, D.; Drogoudi, P.; Rovira, M.; Silva, A.P.; Solar, A.; Botta, R. Fatty acids and alpha-tocopherol composition in hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.): A chemometric approach to emphasize the quality of European germplasm. Euphytica 2013, 191, 57–73.

- Shao, F.; Wilson, I.W.; Qiu, D. The research progress of taxol in Taxus. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2021, 22, 360–366.

- Gallego, A.; Malik, S.; Yousefzadi, M.; Makhzoum, A.; Tremouillaux-Guiller, J.; Bonfill, M. Taxol from Corylus avellana: Paving the way for a new source of this anti-cancer drug. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2017, 129, 1–16.

- Bottone, A.; Cerulli, A.; D’Urso, G.; Masullo, M.; Montoro, P.; Napolitano, A.; Piacente, S. Plant specialized metabolites in hazelnut (Corylus avellana) kernel and byproducts: An update on chemistry, biological activity, and analytical aspects. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 840–855.

- Barss, H.P. A new filbert disease in Oregon. Oregon Agric. Coll. Exp. Sta. Biennial Crop Pest Hort. Rep. 1913, 14, 213–223.

- Miller, P.W.; Bollen, W.B.; Simmons, J.E.; Gross, H.N.; Barss, H.P. The pathogen of filbert bacteriosis compared with Phytomonas juglandis, the cause of walnut blight. Phytopathology 1940, 30, 713–733.

- Sutic, D. Bacterial spots on leaves of filbert. Zast Biija 1956, 37, 47–53.

- Noviello, C. Osservazioni sulle malattie parassitarie del nocciolo, con particolare riferimento alla Campania. Ann. Fac. Sci. Agrar. Univ. Studi Napoli Portici 1968, 3, 11–39.

- Alay, K.; Altinyay, N.; Hancioglu, O.; Dundar, F.; Unal, A. Studies on desiccation of hazel nut branches in the Black Sea region. Bitki Koruma Bul. 1973, 13, 202–213.

- Luisetti, J.; Jailloux, F.; Germain, E.; Prunier, J.P.; Gardan, L. Caracterisation de Xanthomonas corylina (Miller et al.) Starr et Burkholder responsable de la bacteriose du noisetier recemment observee en France. Compte Rendu Acad. Agric. Fr. 1975, 61, 845–849.

- Koval, G.K. Diseases of hazel. Zashchita Rastenii 1978, 8, 44–45.

- Locke, T.; Barnes, D. Xanthomonas corylina on cob-nuts and filberts. Plant Pathol. 1979, 28, 53.

- Wimalajeewa, D.L.S.; Washington, W.S. Bacterial blight of hazelnut. Australas. Plant Pathol. 1980, 9, 113–114.

- Guerrero, C.J.; Lobos, A.W. Xanthomonas campestris pv. corylina, causal agent of bacterial blight of hazel in Region IX, Chile. Agric. Técnica 1987, 47, 422–426.

- Kazempour, M.N.; Ali, B.; Elahinia, S.A. First report of bacterial blight of hazelnut caused by Xanthomonas arboricola pv. corylina in Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 2006, 88, 341.

- Pulawska, J.; Kaluzna, M.; Kolodziejska, A.; Sobiczewski, P. Identification and characterization of Xanthomonas arboricola pv. corylina causing bacterial blight of hazelnut: A new disease in Poland. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 92, 803–806.

- Kałużna, M.; Fischer-Le Saux, M.; Pothier, J.F.; Jacques, M.A.; Obradović, A.; Tavares, F.; Stefani, E. Xanthomonas arboricola pv. juglandis and pv. corylina: Brothers or distant relatives? Genetic clues, epidemiology, and insights for disease management. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2021, 22, 1481–1499.

- Webber, J.B.; Putnam, M.; Serdani, M.; Pscheidt, J.W.; Wiman, N.G.; Stockwell, V.O. Characterization of isolates of Xanthomonas arboricola pv. corylina, the causal agent of bacterial blight, from Oregon hazelnut orchards. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 102, 799–812.

- Webber, J.B.; Wada, S.; Stockwell, V.O.; Wiman, N.G. Susceptibility of some Corylus avellana L. cultivars to Xanthomonas arboricola pv. corylina. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 800339.

- EFSA Panel on Plant Health (PLH); Bragard, C.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Di Serio, F.; Jacques, M.A.; Miret, J.A.J.; Justesen, A.F.; MacLeod, A.; Magnusson, C.S.; Milonas, P.; et al. Commodity risk assessment of Corylus avellana and Corylus colurna plants from Serbia. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06571.

- Lamichhane, J.R.; Varvaro, L. Xanthomonas arboricola disease of hazelnut: Current status and future perspectives for its management. Plant Pathol. 2014, 63, 243–254.

- Scortichini, M.; Rossi, M.P.; Marchesi, U. Genetic, phenotypic and pathogenic diversity of Xanthomonas arboricola pv. corylina strains question the representative nature of the type strain. Plant Pathol. 2002, 51, 374–381.

- Fischer-Le Saux, M.; Bonneau, S.; Essakhi, S.; Manceau, C.; Jacques, M.A. Aggressive emerging pathovars of Xanthomonas arboricola represent widespread epidemic clones distinct from poorly pathogenic strains, as revealed by multilocus sequence typing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 4651–4668.

- Caballero, J.I.; Zerillo, M.M.; Snelling, J.; Boucher, C.; Tisserat, N. Genome sequence of Xanthomonas arboricola pv. corylina, isolated from Turkish filbert in Colorado. Genome Announ. 2013, 1, e00246-13.

- Pothier, J.F.; Kałużna, M.; Prokić, A.; Obradović, A.; Rezzonico, F. Complete genome and plasmid sequence data of three strains of Xanthomonas arboricola pv. corylina, the bacterium responsible for bacterial blight of hazelnut. Phytopathology 2022, 112, 956–960.

- Psallidas, P.G.; Panagopoulos, C.G. A bacterial canker of Corylus avellana in Greece. J. Phytopathol. 1979, 94, 103–111.

- Psallidas, P.G. Pseudomonas syringae pv. avellanae pathovar nov., the bacterium causing canker disease on Corylus avellana. Plant Pathol. 1993, 42, 358–363.

- Scortichini, M.; Tropiano, F.G. Severe outbreak of Pseudomonas syringae pv. avellanae on hazelnut in Italy. J. Phytopathol. 1994, 140, 65–70.

- Brzezinski, M.G. Le chancre des arbres, ses causes et ses symptoms. Bull. Intern. Acad. Sci. Cracovie 1903, 7, 139–140.

- Thornberry, H.H.; Anderson, H.W. Some bacterial diseases of plants in Illinois. Phytopathology 1937, 27, 946–949.

- Janse, J.D.; Rossi, P.; Angelucci, L.; Scortichini, M.; Derks, J.H.J.; Akkermans, A.D.L.; De Vrijer, R.; Psallidas, P.G. Reclassification of Pseudomonas syringae pv. avellanae as Pseudomonas avellanae (spec. nov, the bacterium causing canker of hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1996, 19, 589–595.

- Marcelletti, S.; Scortichini, M. Definition of plant-pathogenic Pseudomonas genomospecies of the P. syringae complex through multiple comparative approaches. Phytopathology 2014, 104, 1274–1282.

- Scortichini, M.; Marchesi, U.; Dettori, M.T.; Angelucci, L.; Rossi, M.P.; Morone, C. Genetic and pathogenic diversity of Pseudomonas avellanae strains isolated from Corylus avellana trees in north-west of Italy, and comparison with strains from other regions. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2000, 106, 147–154.

- Scortichini, M.; Marchesi, U.; Rossi, M.P.; Di Prospero, P. Bacteria associated with hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) decline are of two groups: Pseudomonas avellanae and strains resembling P. syringae pv. syringae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 476–484.

- Kaluzna, M.; Ferrante, P.; Sobiczewski, P.; Scortichini, M. Characterization and genetic diversity of Pseudomonas syringae from stone fruits and hazelnut using repetitive-PCR and MLST. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 92, 781–787.

- Scortichini, M.; Rossi, M.P.; Loreti, S.; Bosco, A.; Fiori, M.; Jackson, R.W.; Stead, D.E.; Aspin, A.; Marchesi, U.; Zini, M.; et al. Pseudomonas syringae pv. coryli, the causal agent of bacterial twig dieback of Corylus avellana. Phytopathology 2005, 95, 1316–1324.

- Scortichini, M.; Marcelletti, S.; Ferrante, P.; Firrao, G. A genomic redefinition of Pseudomonas avellanae species. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75794.

- Berge, O.; Monteil, C.L.; Bartoli, C.; Chandeysson, C.; Guilbaud, C.; Sands, D.C.; Morris, C.E. A user’s guide to a data base of the diversity of Pseudomonas syringae and its application to classifying strains in this phylogenetic complex. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105547.

- Scortichini, M.; Ferrante, P.; Cozzolino, L.; Zoina, A. Emended description of Pseudomonas syringae pv. avellanae, causal agent of European hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) bacterial canker and decline. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 144, 213–215.

- Marcelletti, S.; Scortichini, M. Comparative genomic analyses of multiple Pseudomonas strains infecting Corylus avellana trees reveal the occurrence of two genetic clusters with both common and distinctive virulence and fitness traits. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131112.

- Turco, S.; Zuppante, L.; Drais, M.I.; Mazzaglia, A. Dressing like a pathogen: Comparative analysis of different Pseudomonas genomospecies wearing different features to infect Corylus avellana. J. Phytopathol. 2022, 170, 504–516.

- Maleki-Zadeh, H.R.; Falahi Charkhabi, N.; Khodaygan, P.; Rahimian, H. Bacterial leaf spot and die-back of hazelnut caused by a new pathovar of Pseudomonas amygdali. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 163, 293–303.

- Bucini, D.; Balestra, G.M.; Pucci, C.; Paparatti, B.; Speranza, S.; Proietti Zolla, C.; Varvaro, L. Bio-ethology of Anisandrus dispar F. and its possible involvement in dieback (Moria) diseases of hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) plants in central Italy. Acta Hort. 2004, 686, 435–444.

- Guerrero, J.C.; Pérez, S.F.; Ferrada, E.Q.; Cona, L.Q.; Bensch, E.T. Phytopathogens of hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) in southern Chile. Acta Hort. 2014, 1052, 269–274.

- Krol, E.; Machowicz-Stefaniak, Z.; Zalewska, E. Bacteria damaging the fruit of hazel (Corylus avellana L.) cultivated in South-East Poland. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2004, 3, 75–84.

- Marcone, C.; Ragozzino, A.; Seemüller, E. Association of phytoplasmas with the decline of European hazel in southern Italy. Plant Pathol. 1996, 45, 857–863.

- Postman, J.D.; Johnson, K.B.; Jomantiene, R.; Maas, J.L.; Davis, R.E. The Oregon hazelnut stunt syndrome and phytoplasma associations. Acta Hort. 2001, 556, 407–409.

- Cieślińska, M.; Kowalik, B. Detection and molecular characterization of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’ in European hazel (Corylus avellana) in Poland. J. Phytopathol. 2011, 159, 585–588.

- Hodgetts, J.; Flint, L.J.; Davey, C.; Forde, S.; Jackson, L.; Harju, V.; Skelton, A.; Fox, A. Identification of’ Candidatus Phytoplasma fragariae’(16Sr XII-E) infecting Corylus avellana (hazel) in the United Kingdom. New Dis. Rep. 2015, 32, 3.

- Mehle, N.; Jakoš, N.; Mešl, M.; Miklavc, J.; Matko, B.; Rot, M.; Ferlež Rus, A.; Brus, R.; Dermastia, M. Phytoplasmas associated with declining of hazelnut (Corylus avellana) in Slovenia. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 155, 1117–1132.

- Gentili, A.; Donati, L.; Bertin, S.; Manglli, A.; Ferretti, L. First report of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma fragariae’ infecting hazelnut in Italy. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 2254.

- Lessio, F.; Picciau, L.; Gonella, E.; Tota, F.; Mandrioli, M.; Alma, A. The mosaic leafhopper Orientus ishidae: Host plants, spatial distribution, infectivity, and transmission of 16SrV phytoplasmas to vines. Bull. Insectol. 2016, 69, 277–289.

- Mehle, N.; Dermastia, M. Towards the evaluation of potential insect vectors of phytoplasmas infecting hazelnut plants in Slovenia. Phytopath. Mollicutes 2019, 9, 49–50.

- Vuono, G.; Balestra, G.M.; Varvaro, L. Control of dieback (“Moria”) of Corylus avellana in central Italy using copper compounds. J. Plant Pathol. 2006, 88, 215–218.

- Scortichini, M.; Liguori, R. Integrated management of bacterial decline of hazelnut, by using Bion as an activator of systemic acquired resistance (SAR). In Pseudomonas Syringae and Related Pathogens; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 483–487.

- Schiavi, D.; Ronchetti, R.; Di Lorenzo, V.; Salustri, M.; Petrucci, C.; Vivani, R.; Giovagnoli, S.; Camaioni, E.; Balestra, G.M. Circular hazelnut protection by lignocellulosic waste valorization for nanopesticides development. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2604.

- Pisetta, M.; Albertin, I.; Petriccione, M.; Scortichini, M. Effects of hot water treatment to control Xanthomonas arboricola pv. corylina on hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) propagative material. Sci. Hort. 2016, 211, 187–193.

- Prokić, A.; Ivanović, M.; Gasic, K.; Kuzmanovic, N.; Zlatković, N.; Obradovic, A. Studying Xanthomonas arboricola pv. corylina strains from Serbia for streptomycin and kasugamycin resistance and copper sulfate sensitivity in vitro. In Proceedings of the 12th International Congress of Plant Pathology: Plant Health in a Global Economy, Boston, MA, USA, 29 July–3 August 2018; Available online: https://apsnet.confex.com/apsnet/ICPP2018/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/11264 (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Arena, M.; Auteri, D.; Barmaz, S.; Bellisai, G.; Brancato, A.; Brocca, D.; Bura, L.; Byers, H.; Chiusolo, A.; et al. Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance copper compounds copper(I), copper(II) variants namely copper hydroxide, copper oxychloride, tribasic copper sulfate, copper(I) oxide, Bordeaux mixture. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05152.