Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Conner Chen and Version 2 by Conner Chen.

One interesting compound in the spectrum of cyanobacterial metabolites is the non-proteinogenic amino acid β-N-methylamino-L-alanine, abbreviated BMAA. In total, the presence of BMAA and/or its isomers was linked to more than 200 findings related to cyanobacteria from nature (freshwaters, marine and brackish environment, terrestrial habitats and plant symbionts), market samples and specimens from culture collections. Although BMAA and its isomers are found in many ecosystems, the occurrence of these compounds is not ubiquitous.

- cyanobacteria

- β-N-methylamino-L-alanine

- BMAA

1. Introduction

Some strains of cyanobacteria are known to produce potent hepato-, cyto-, neuro- and/or dermatotoxins and other bioactive compounds [1]. Blooms of cyanobacteria and cyanobacteria-associated health problems have been documented throughout the world [2][3]. Many cyanobacterial poisonings can be traced back to microcystins, cyanobacterial peptide hepatotoxins, tumor promoters and possible carcinogens, which may pose a serious threat to health through contaminated drinking water [4]. Other cyanobacterial toxins (cyanotoxins) include compounds from the groups of cylindrospermopsins (cytotoxins), anatoxins and saxitoxins (neurotoxins) and nodularins (hepatotoxins, tumor promoters and possible carcinogens). All of these toxins have been implicated in cyanobacterial poisonings of either humans or animals.

One interesting compound in the spectrum of cyanobacterial metabolites is the non-proteinogenic amino acid β-N-methylamino-L-alanine, abbreviated BMAA. This compound, according to systematic chemical nomenclature (S)-2-amino-3-methylaminopropanoic acid (L-BMAA), has the natural isomers (S)-2,4-diaminobutyric acid (L-DAB), N-(2-aminoethyl)glycine (AEG) and β-amino-N-methylalanine (BAMA) [5].

BMAA was first observed in cycad seeds some 55 years ago [6], and its occurrence and properties continue to inspire scientists of various disciplines [7]. BMAA has been suggested to play a causal role in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/Parkinsonism-dementia complex (ALS/PDC), found at an elevated incidence in the Chamorro people of the Pacific island of Guam [8]. The Chamorro people are thought to become exposed to the neurotoxin through the use of cycad seed flour contaminated by BMAA originating from symbiotic cyanobacteria. As BMAA can be found or even biomagnified in certain food web compartments [8][9][10] it is also possible that a major share of the BMAA exposure on Guam occurs through the traditional consumption of cycad-feeding bats.

Early research pointed to a wide occurrence of BMAA in free-living and symbiotic cyanobacteria in many parts of the world, at up to mg/g DW (dry weight) levels [11]. Another paper from South Africa confirmed the taxonomic ubiquity of BMAA in freshwater cyanobacteria, but the reported toxin concentrations were lower [12]. BMAA was found in combination with additional cyanotoxins in British waterbodies [13]. In contrast, a study involving 62 cyanobacterial samples of worldwide origin found no BMAA in any of the cyanobacterial samples [14]. BMAA has also been reported in other groups of microalgae. The extent of BMAA production by cyanobacteria and other organisms may not thus be fully understood, but it seems a widely observed phenomenon. Out of 74 publications dealing with BMAA detection and quantification in samples of cyanobacteria or human tissues, only 12 failed to detect a BMAA signal in environmental samples [15]. Less is known about the transfer and possible biomagnification of BMAA in food webs. Further, it is not fully understood how much of the toxin occurs in free, protein-bound or soluble-bound forms [16] and whether such a bound toxin is bioavailable.

Some of the BMAA analytical protocols have been shown to suffer from methodological problems or at least from poor reporting [17], and therefore, especially older literature must be treated with caution. Analytical methods relying on liquid chromatography and fluorescence detection of derivatized BMAA seem to be more prone to report either false positives or an overestimation of BMAA concentration in the studied samples. More selective and sufficiently validated analytical protocols involving appropriate sample preparation and relying on liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) for the detection and quantification of (derivatized) BMAA have overcome most, but not all, of the methodological challenges [15][18]. The AOAC (Association of Official Analytical Chemists)-accepted method for BMAA in a cyanobacterial matrix is based on ultra-performance liquid chromatography of AQC (6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate )-derivatized BMAA and tandem mass spectrometry [19].

2. Occurrence of BMAA

2.1. Occurrence of BMAA in Cyanobacteria and Microalgae

Based on the published papers (Occurrence of BMAA and its isomers in environmental samples and organisms), BMAA and its isomers (DAB and AEG) were found to be produced by cyanobacteria belonging to 29 genera: Anabaena [11][13][14][20][21][22][23], Anabaenopsis [23], Aphanizomenon [11][13][20][22][24][25], Calothrix [11][20][26], Chlorogloeopsis [11], Chroococcidiopsis [11][23], Cyanobium [27][28], Cylindrospermopsis [11][14], Fischerella [11][23], Gomphosphaeria [13], Leptolyngbya [24][26][27][28][29][30], Lyngbya [11][20][23], Microcoleus [27][28], Microcystis [11,13,14,23–25, 34], Myxosarcina [11][31], Nodularia [11][13][14][23][24][27][28], Nostoc [8][11][20][23][26][27][28][31][32], Oscillatoria [13][23], Phormidium [11][23][27][28], Planktothrix [11][13][20][22], Plectonema [11], Prochlorococcus [11], Pseudanabaena [13], Scytonema [11][20], Symploca [11][26], Synechococcus [10][11][20][26][27][28], Synechocystis [23][27][28], Trichodesmium [11] and Woronichinia [22]. These cyanobacteria represented: (a) a biomass of cyanobacteria collected from: freshwater (40 reports from different localities), marine (5 reports) and brackish (1 report) environments and (b) cultures of cyanobacterial strains originating from freshwaters (28 strains), marine habitats (14 strains), brackish waters (33 strains), symbiotic plants (10 strains) and terrestrial environments (4 strains). For 32 strains, the origin could not be found in the corresponding publications. There are also some reports about the presence of BMAA and/or its isomers in the biomass of collected cyanobacteria, but the producers were not identified [9][10][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40]. BMAA and its isomers have been found in 22 supplements made of biomass of the cyanobacteria Spirulina [19][32][41] and Aphanizomenon [14][42]. The compounds have been also detected in cyanobacterial biocrust samples from Qatar [43][44][45][46] and aerosols (air-filters from the lakeshore) [47]. In total, the presence of BMAA and/or its isomers was linked to more than 200 findings related to cyanobacteria from nature (freshwaters, marine and brackish environment, terrestrial habitats and plant symbionts), market samples and specimens from culture collections. Although BMAA and its isomers are found in many ecosystems, the occurrence of these compounds is not ubiquitous. A total of 387 environmental and biological samples (water, fish, aquatic plants) taken from Nebraska (USA) were analysed for BMAA, DABA and anatoxin-a (a compound unrelated to BMAA and DABA). Measurable levels of BMAA, DABA and anatoxin-a were found in 18%, 17% and 12% of the samples, respectively [34]. In a study involving bloom-impacted lakes and reservoirs of Brazil, Canada, France, Mexico and the United Kingdom, 390 samples were taken from 45 lake sampling sites. AEG and DAB isomers were detected in 30% and 43% of the samples, respectively, while BAMA was found in less than 8% of the samples and BMAA was not observed in any sample [33]. No BMAA was found in any of the analyzed biological loess crusts (BLCs, terrestrial samples) taken from various locations in Serbia, China and Iran [48]. These results indicate that while BMAA occurs in many ecosystems, it is not present in every ecosystem. The results also underline the need to look for the isomers of BMAA (DAB, AEG, BAMA) in order to get a more complete picture of the occurrence of the BMAA family of compounds. It can also be noted that the BMAA and isomer concentrations are not stable in one ecosystem but vary temporally and spatially. They depend on when (daily, monthly and annual variations), where and how the samples have been taken from a waterbody, and how the samples have been analyzed. Further, BMAA can be found in either free or bound forms which necessitate due attention during the analysis and reporting [16]. Comparisons are therefore more meaningful within one publication with a consistent methodology. The physico-chemical environment also seems to have an influence on the BMAA concentration. BMAA in environmental phytoplankton samples ranged from 1 µg/g to 276 μg/g DW, while cultures had higher values ranging from 20 µg/g to 6.4 mg/g DW [49]. One of the most extensive analytical studies on the occurrence of BMAA isomers in bloom-impacted lakes and reservoirs analyzed environmental water samples from five countries [33]. The study did not detect BMAA in any of the samples but observed isomers at the following min-max concentrations: 10–1100 ng/L (DAB), 5–19,000 ng/L (AEG) and 15–56 ng/L (BAMA). The same paper [33] further presented widely varying BMAA isomer concentrations in environmental water samples reported in previously published studies. For instance, the reported BMAA concentrations in environmental waters in the paper [33] and four earlier papers cited therein varied dramatically: not detected, 6.5–7 ng/L (mean values from two years), 10–300 ng/L, 110 ng/L, 1800–25,300 ng/L. There are reports that planktonic diatoms (Bacillariophyta), dinoflagellates (Pyrrhophyta), green algae (Chlorophyta), euglenas (Euglenophyta), red algae (Rhodophyta), Haptophyta and Cryptophyta also produce BMAA and/or its isomers. Diatoms are represented by 15 genera: Achnanthes [30], Asterionellopsis [50], Aulacoseira [51], Chaetoceros [10][52], Cyclotella [51], Fragilaria [51], Halamphora [50], Navicula [30][51], Odontella [50], Phaeodactylum [10][52], Proboscia [30], Pseudo-nitzschia [50], Skeletonema [10][30], Tabellaria [51] and Thalassiosira [10][30][52]; dinoflagellates by seven genera: Alexandrium [10][50], Gymnodinium [53], Heterocapsa [50], Prorocentrum [50], Pyrocystis [50], Scrippsiella [50] and Symbiodinium [50]; green algae by four genera: Ostreococcus [10], Chlamydomonas [50], Chlorella [50] and Dunaliella [50]; Euglenophyta and Rhodophyta by one genus each: Eutreptiella [50] and Porphyridium [50], respectively; Haptophyta by two genera: Tisochrysis [50] and Emiliana [50]; and Cryptophyta by four genera: Hemiselmis [50], Proteomonas [50], Rhinomonas [50] and Rhodomonas [50] isolated from marine and freshwater environments.2.2. Occurrence of BMAA in Animals

BMAA has also been detected in the zooplankton community in the Baltic Sea [9][40]. The presence of BMAA and its isomers in zooplankton organisms, molluscs, crustaceans, fish, birds, mammals and other animals is a consequence of the bioaccumulation of BMAA in food webs [8][37][54]. In the group of molluscs, BMAA was found in bivalvia Anodonta woodiana [55], Antigona lamellaris [56], Arca inflate [56], Atrina pectinate [56], Cerastoderma edule [53], Chlamys farreri [56], Corbicula fluminea [55], Crassosstrea sp. [56], Crassosstrea gigas [26][50][57], Crassostrea virginica [58], Gafrarium tumidum [56], Mactra chinensis [56], Mercenaria mercenaria [56], Moerella iridescens [56], Mytilus coruscus [56], Mytilus edulis [9][50][57][59], Mytilus edulis platensis [59], Mytilus galloprovincialis [10][26][50][56], Ostrea edulis [9][24][57], Periglypta petechialis [56], Perna canaliculus [59], Perna viridis [56], Placopecten magellanicus [59], Ruditapes philippinarum [56], Scapharca subcrenata [56], Sinonovacula constricta [56], Solen strictus [56], Tegillarca granosa [56] and an unidentified mussel [60]. BMAA was also found in gastropods Bellamya aeruginosa [55], Neverita didyma [56], Neptunea cumingii [56], Natica maculosa [56], Haliotis discus hannai [56], Volutharpa ampullaceal [56] and Rapana venosa [56]. The arthropods (Crustacea) in which BMAA was found are represented by ten species: Callinectes sapidus [32][58][61], Cancer pagurus [59], Heterocarpus ensifer [57], Eriocheir sinensis [55], Macrobrachium nipponense [55], Mysis mixta [40], Neomysis integer [40], Palaemon modestus [55], Panulirus sp. [62] and Procambarus clarkia [55]. In the tissues of the fish, there was evidence of accumulation of BMAA after the consumption of BMAA producers, mostly cyanobacteria. A total of 39 species of fish showed the presence of BMAA in their tissues: Abramis brama [53], Anguilla anguilla [53], Aristichthys nobilis [55], Carassius auratus [55], Carcharhinus acronotus [63][64], Carcharhinus leucas [63][64], Carcharhinus limbatus [63][64], Clupea harengus [9][57], Coilia ectenes taihuensis [55], Coregonus lavaretus [9][24], Cyprinus carpio [47][55], Erythroculter ilishaeformis [55], Esox lucius [53], Galeocerdo cuvier [64], Ginglymostoma cirratum [63][64], Gymnocephalus cernua [53], Hemiramphus kurumeus [55], Hypophthalmichthys molitrix [55], Neosalanx taihuensis [55], Negaprion brevirostris [63][64], Osmerus eperlanus [9], Parabramis pekinensis [55], Parasilurus asotus [55], Pelteobagrus fulvidraco [55], Perca fluviatilis [53], Pleuronectes platessa [57], Protosalanx hyalocranius [55], Pseudorasbora parva [55], Rhizoprionodon terraenovae [64], Rhodeus sinensis [55], Rutilus rutilus [53], Salvelinus alpinus [57], Sander lucioperca [53], Scophthalmus maximus [9], Sphyrna mokarran [63][64], Sphyrna tiburo [63][64], Sphyrna zygaena [64], Tinca tinca [53] and Triglopsis quadricornis [9]. Fish samples from Nebraska reservoirs (carp, white crappie, bass, shad, walleye, catfish, wiper and bluegill) showed the presence of BMAA, and in many samples, also the presence of DAB [34]. BMAA, DAB and/or AEG were found in 16 fish-based dietary supplements (shark cartilage powders) from seven manufacturers [65]. The reports about mammals showed that BMAA was detected in flying foxes [37][66], in dolphins [67] and in human brain tissue from some patients who died from ALS [8][37][68]. It was also found in human hair [69].2.3. Occurrence of BMAA in Plants

BMAA and/or its isomers were found in parts of the following symbiotic and other plants: Azolla filiculoides [8], Brassica oleracea [24], Cycas micronesica [8][25][37][70], Cycas revoluta [14][20][24], Cycas debaoensis [41], Gunnera kauaiensi [8], Lathyrus latifolius [14] and aquatic plants from Nebraska [34]. BMAA was found in flour prepared from the gametophyte of cycad seeds [37].2.4. Exposure to BMAA

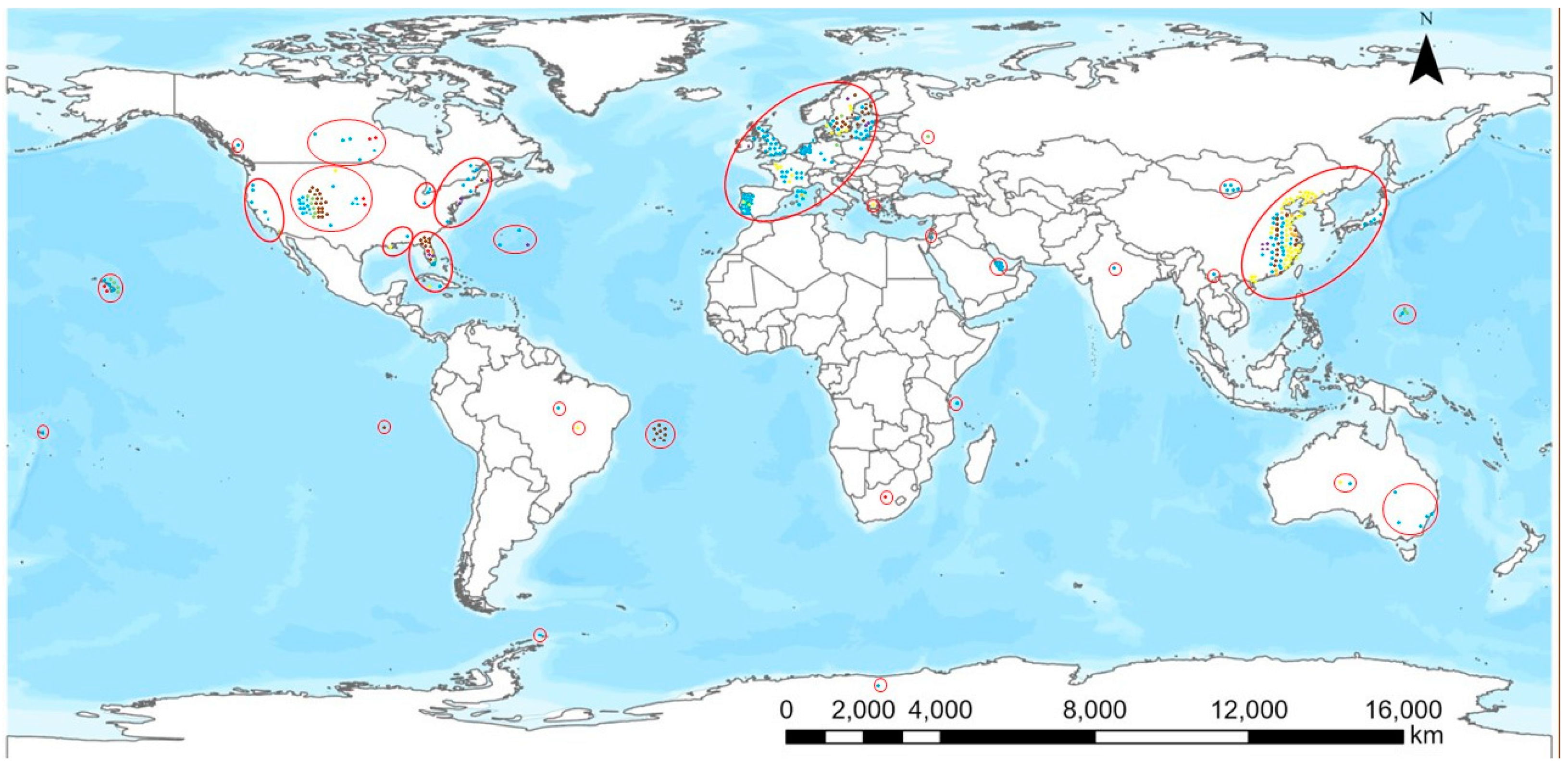

Exposure to BMAA can occur through the same routes of exposure that are known for other cyanotoxins: through drinking water (e.g., in a case when a cyanobacterial mass development occurs in a drinking water reservoir), recreational activities (e.g., swimming, canoeing or bathing), the aquatic food web, terrestrial plants and animals and food supplements [49][71][72][73]. Synthesized by cyanobacteria and microalgae, BMAA is transported through some food webs in aquatic ecosystems from zooplankton and benthos invertebrates, planktivorous fish, shellfish, snails and crustaceans to carnivorous fish and mammals. Human contact with BMAA is possible through all these food web compartments in aquatic ecosystems. In terrestrial ecosystems, BMAA can be found in some symbioses of cyanobacteria with higher plants, but it can also be transferred from aquatic ecosystems into terrestrial ecosystems through irrigation. As a consequence of irrigation with BMAA-contaminated water, BMAA can be accumulated in plant tissues and thus reach animals and humans. As presented in Figure 1, BMAA and/or its isomers have been found throughout the world and exposure scenarios either through contaminated drinking water or consumption of contaminated foodstuffs are present in most parts of the world. There are clearly some hotspots of BMAA occurrence: parts of Europe, the United States and China as well as some islands including Guam. The largest number of reports deal with European countries which could be an indication of active research on the topic there. The absence of reports from, e.g., most African, Asian and South American countries probably does not mean the absence of BMAA and its isomers in these parts of the world, but that those territories were not as thoroughly investigated as for instance Western European countries. The situation with BMAA is similar to that of cylindrospermopsin which was first thought to be a tropical toxin. Generally speaking, cylindrospermopsin has been found in most countries where it has been looked for carefully enough and this is the likely scenario with BMAA, too.

Figure 1. Geographical distribution of the occurrence of BMAA and its isomers. Color coding of the dots: phytoplankton and zooplankton, blue; plants, green; bivalvia, yellow; gastropoda, orange; crustacea, purple; fish, brown; mammals, red.

References

- Meriluoto, J.; Spoof, L.; Codd, G.A. (Eds.) Handbook of Cyanobacterial Monitoring and Cyanotoxin Analysis; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2017; p. 548.

- Svirčev, Z.; Drobac, D.; Tokodi, N.; Mijović, B.; Codd, G.A.; Meriluoto, J. Toxicology of microcystins with reference to cases of human intoxications and epidemiological investigations of exposures to cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 621–650.

- Svirčev, Z.; Lalić, D.; Bojadžija Savić, G.; Tokodi, N.; Drobac, D.; Chen, L.; Meriluoto, J.; Codd, G.A. Global geographical and historical overview of cyanotoxin distribution and cyanobacterial poisonings. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 2429–2481.

- Svirčev, Z.; Drobac, D.; Tokodi, N.; Đenić, D.; Simeunović, J.; Hiskia, A.; Kaloudis, T.; Mijović, B.; Šušak, S.; Protić, M.; et al. Lessons from the Užice case: How to complement analytical data. In Handbook of Cyanobacterial Monitoring and Cyanotoxin Analysis; Meriluoto, J., Spoof, L., Codd, G.A., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 298–308.

- Ploux, O.; Combes, A.; Eriksson, J.; Metcalf, J.S. β-N-methylamino-L-alanine and (S)-2,4-diaminobutyric acid. In Handbook of Cyanobacterial Monitoring and Cyanotoxin Analysis; Meriluoto, J., Spoof, L., Codd, G.A., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 160–164.

- Vega, A.; Bell, E.A. α-Amino-β-methylaminopropionic acid, a new amino acid from seeds of Cycas circinalis. Phytochemistry 1967, 6, 759–762.

- Nunn, P.B. 50 years of research on α-amino-β-methylaminopropionic acid (β-methylaminoalanine). Phytochemistry 2017, 144, 271–281.

- Cox, P.A.; Banack, S.A.; Murch, S.J. Biomagnification of cyanobacterial neurotoxins and neurodegenerative disease among the Chamorro people of Guam. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 13380–13383.

- Jonasson, S.; Eriksson, J.; Berntzon, L.; Spáčcil, Z.; Ilag, L.L.; Ronnevi, L.-O.; Rasmussen, U.; Bergman, B. Transfer of a cyanobacterial neurotoxin within a temperate aquatic ecosystem suggests pathways for human exposure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9252–9257.

- Réveillon, D.; Abadie, E.; Séchet, V.; Masseret, E.; Hess, P.; Amzil, Z. β-N-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) and isomers: Distribution in different food web compartments of Thau lagoon, French Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 110, 8–18.

- Cox, P.A.; Banack, S.A.; Murch, S.J.; Rasmussen, U.; Tien, G.; Bidigare, R.R.; Metcalf, J.S.; Morrison, L.F.; Codd, G.A.; Bergman, B. Diverse taxa of cyanobacteria produce β-N-methylamino-L-alanine, a neurotoxic amino acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5074–5078.

- Esterhuizen, M.; Downing, T.G. β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) in novel South African cyanobacterial isolates. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2008, 71, 309–313.

- Metcalf, J.S.; Banack, S.A.; Lindsay, J.; Morrison, L.F.; Cox, P.A.; Codd, G.A. Co-occurrence of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine, a neurotoxic amino acid with other cyanobacterial toxins in British waterbodies, 1990–2004. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 702–708.

- Krüger, T.; Mönch, B.; Oppenhäuser, S.; Luckas, B. LC-MS/MS determination of the isomeric neurotoxins BMAA (β-N-methylamino-L-alanine) and DAB A mechanism for slow release (2,4-diaminobutyric acid) in cyanobacteria and seeds of Cycas revoluta and Lathyrus latifolius. Toxicon 2010, 55, 547–557.

- Banack, S.A.; Murch, S.J. Methods for the chemical analysis of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine: What is known and what remains to be determined. Neurotox. Res. 2018, 33, 184–191.

- Faassen, E.J.; Antoniou, M.G.; Beekman-Lukassen, W.; Blahova, L.; Chernova, E.; Christophoridis, C.; Combes, A.; Edwards, C.; Fastner, J.; Harmsen, J.; et al. A collaborative evaluation of LC-MS/MS based methods for BMAA analysis: Soluble bound BMAA found to be an important fraction. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 45.

- Faassen, E.J. Presence of the neurotoxin BMAA in aquatic ecosystems: What do we really know? Toxins 2014, 6, 1109–1138.

- Bishop, S.L.; Murch, S.J. A systematic review of analytical methods for the detection and quantification of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA). Analyst 2020, 145, 13–28.

- Glover, W.B.; Baker, T.C.; Murch, S.J.; Brown, P.N. Determination of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine, N-(2-aminoethyl)glycine, and 2,4-diaminobutyric acid in food products containing cyanobacteria by ultra-performance liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry: Single-laboratory validation. J. AOAC Int. 2015, 98, 1559–1565.

- Fan, H.; Qiu, J.; Fan, L.; Li, A. Effects of growth conditions on the production of neurotoxin 2,4-diaminobutyric acid (DAB) in Microcystis aeruginosa and its universal presence in diverse cyanobacteria isolated from freshwater in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 5943–5951.

- Craighead, D.; Metcalf, J.S.; Banack, S.A.; Amgalan, L.; Reynolds, H.V.; Batmunkh, M. Presence of the neurotoxic amino acids beta-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) and 2,4-diamino-butyric acid (DAB) in shallow springs from the Gobi Desert. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2009, 10 (Suppl. 2), 96–100.

- Faassen, E.J.; Gillissen, F.; Zweers, H.A.; Lürling, M. Determination of the neurotoxins BMAA (β-N-methylamino-L-alanine) and DAB (alpha-,gamma-diaminobutyric acid) by LC-MSMS in Dutch urban waters with cyanobacterial blooms. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2009, 2, 79–84.

- Banack, S.A.; Metcalf, J.S.; Jiang, L.; Craighead, D.; Ilag, L.L.; Cox, P.A. Cyanobacteria produce N-(2-aminoethyl)glycine, a backbone for peptide nucleic acids which may have been the first genetic molecules for life on Earth. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49043.

- Spáčil, Z.; Eriksson, J.; Jonasson, S.; Rasmussen, U.; Ilag, L.L.; Bergmana, B. Analytical protocol for identification of BMAA and DAB in biological samples. Analyst 2010, 135, 127–132.

- Faassen, E.J.; Gillissen, F.; Lürling, M. A comparative study on three analytical methods for the determination of the neurotoxin BMAA in cyanobacteria. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36667.

- Réveillon, D.; Abadie, E.; Séchet, V.; Brient, L.; Savar, V.; Bardouil, M.; Hess, P.; Amzil, Z. Beta-N-methylamino-L-alanine: LC-MS/MS optimization, screening of cyanobacterial strains and occurrence in shellfish from Thau, a French Mediterranean lagoon. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 5441–5467.

- Baptista, M.S.; Cianca, R.C.; Lopes, V.R.; Almeida, C.M.; Vasconcelos, V.M. Determination of the non protein amino acid β-N-methylamino-l-alanine in estuarine cyanobacteria by capillary electrophoresis. Toxicon 2011, 58, 410–414.

- Cervantes Cianca, R.C.; Baptista, M.S.; Lopes, V.R.; Vasconcelos, V.M. The non-protein amino acid β-N-methylamino-L-alanine in Portuguese cyanobacterial isolates. Amino Acids 2012, 42, 2473–2479.

- Jiang, L.; Johnston, E.; Aberg, K.M.; Nilsson, U.; Ilag, L.L. Strategy for quantifying trace levels of BMAA in cyanobacteria by LC/MS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 1283–1292.

- Jiang, L.; Eriksson, J.; Lage, S.; Jonasson, S.; Shams, S.; Mehine, M.; Ilag, L.L.; Rasmussen, U. Diatoms: A novel source for the neurotoxin BMAA in aquatic environments. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84578.

- Monteiro, M.; Costa, M.; Moreira, C.; Vasconcelos, V.M.; Baptista, M.S. Screening of BMAA-producing cyanobacteria in cultured isolates and in in situ blooms. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 879–888.

- Baker, T.C.; Tymm, F.J.M.; Murch, S.J. Assessing environmental exposure to β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) in complex sample matrices: A comparison of the three most popular LC-MS/MS methods. Neurotox. Res. 2018, 33, 43–54.

- Abbes, S.; Vo Duy, S.; Munoz, G.; Dinh, Q.T.; Simon, D.F.; Husk, B.; Baulch, H.M.; Vinçon-Leite, B.; Fortin, N.; Greer, C.W.; et al. Occurrence of BMAA isomers in bloom-impacted lakes and reservoirs of Brazil, Canada, France, Mexico, and the United Kingdom. Toxins 2022, 14, 251.

- Al-Sammak, M.A.; Hoagland, K.D.; Cassada, D.; Snow, D.D. Co-occurrence of the cyanotoxins BMAA, DABA and anatoxin-a in Nebraska reservoirs, fish, and aquatic plants. Toxins 2014, 6, 488–508.

- Jungblut, A.D.; Wilbraham, J.; Banack, S.A.; Metcalf, J.S.; Codd, G.A. Microcystins, BMAA and BMAA isomers in 100-year-old Antarctic cyanobacterial mats collected during Captain R.F. Scott’s Discovery Expedition. Eur. J. Phycol. 2018, 53, 115–121.

- Lage, S.; Annadotter, H.; Rasmussen, U.; Rydberg, S. Biotransfer of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) in a eutrophicated freshwater lake. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 1185–1201.

- Murch, S.; Cox, P.A.; Banack, S.A. A mechanism for slow release of biomagnified cyanobacterial neurotoxins and neurodegenerative disease in Guam. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 12228–12231.

- Pip, E.; Munford, K.; Bowman, L. Seasonal Nearshore Occurrence of the Neurotoxin β N methylamino L alanine (BMAA) in Lake Winnipeg, Canada. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 5, 110–118.

- Roy-Lachapelle, A.; Solliec, M.; Sauvé, S. Determination of BMAA and three alkaloid cyanotoxins in lake water using dansyl chloride derivatization and high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 5487–5501.

- Zguna, N.; Karlson, A.M.L.; Ilag, L.L.; Garbaras, A.; Gorokhova, E. Insufficient evidence for BMAA transfer in the pelagic and benthic food webs in the Baltic Sea. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10406.

- McCarron, P.; Logan, A.C.; Giddings, S.D.; Quilliam, M.A. Analysis of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) in spirulina-containing supplements by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Aquat. Biosyst. 2014, 10, 5.

- Roy-Lachapelle, A.; Solliec, M.; Bouchard, M.F.; Sauvé, S. Detection of cyanotoxins in algae dietary supplements. Toxins 2017, 9, 76.

- Chatziefthimiou, A.D.; Banack, S.A.; Cox, P.A. Biocrust-produced cyanotoxins are found vertically in the desert soil profile. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 42–48.

- Cox, P.A.; Richer, R.; Metcalf, J.S.; Banack, S.A.; Codd, G.A.; Bradley, W.G. Cyanobacteria and BMAA exposure from desert dust: A possible link to sporadic ALS among Gulf War veterans. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2009, 10, 109–117.

- Metcalf, J.S.; Banack, S.A.; Richer, R.; Cox, P.A. Neurotoxic amino acids and their isomers in desert environments. J. Arid Environ. 2015, 112, 140–144.

- Richer, R.; Banack, S.A.; Metcalf, J.S.; Cox, P.A. The persistence of cyanobacterial toxins in desert soils. J. Arid Environ. 2015, 112, 134–139.

- Banack, S.A.; Caller, T.; Henegan, P.; Haney, J.; Murby, A.; Metcalf, J.S.; Powell, J.; Cox, P.A.; Stommel, E. Detection of cyanotoxins, β-N-methylamino-L-alanine and microcystins, from a lake surrounded by cases of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Toxins 2015, 29, 322–336.

- Dulić, T.; Svirčev, Z.; Palanački Malešević, T.; Faassen, E.J.; Savela, H.; Hao, Q.; Meriluoto, J. Assessment of common cyanotoxins in cyanobacteria of biological loess crusts. Toxins 2022, 14, 215.

- Manolidi, K.; Triantis, T.M.; Kaloudis, T.; Hiskia, A. Neurotoxin BMAA and its isomeric amino acids in cyanobacteria and cyanobacteria-based food supplements. J. Hazard Mater. 2018, 365, 345–365.

- Réveillon, D.; Séchet, V.; Hess, P.; Amzil, Z. Systematic detection of BMAA (β-N-methylamino-l-alanine) and DAB (2,4-diaminobutyric acid) in mollusks collected in shellfish production areas along the French coasts. Toxicon 2016, 110, 35–46.

- Violi, J.P.; Facey, J.A.; Mitrovic, S.M.; Colville, A.; Rodgers, K.J. Production of β-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) and its Isomers by freshwater diatoms. Toxins 2019, 11, 512.

- Réveillon, D.; Séchet, V.; Hess, P.; Amzil, Z. Production of BMAA and DAB by diatoms (Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Chaetoceros sp., Chaetoceros calcitrans and, Thalassiosira pseudonana) and bacteria isolated from a diatom culture. Harmful Algae 2016, 58, 45–50.

- Lage, S.; Costa, P.R.; Moita, T.; Eriksson, J.; Rasmussen, U.; Rydberg, S.J. BMAA in shellfish from two Portuguese transitional water bodies suggests the marine dinoflagellate Gymnodinium catenatum as a potential BMAA source. Aquat. Toxicol. 2014, 152, 131–138.

- Koksharova, O.A.; Safronova, N.A. Non-proteinogenic amino acid β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA): Bioactivity and ccological significance. Toxins 2022, 14, 539.

- Jiao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Liao, X.; Jiang, L.; Wu, J.; Yang, L. Occurrence and transfer of a cyanobacterial neurotoxin β-methylamino-L-alanine within the aquatic food webs of Gonghu Bay (Lake Taihu, China) to evaluate the potential human health risk. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 468–469, 457–463.

- Li, A.; Song, J.; Hu, Y.; Deng, L.; Ding, L.; Li, M. New typical vector of neurotoxin β-N-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) in the marine benthic ecosystem. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 202.

- Jiang, L.; Kiselova, N.; Rosén, J.; Ilag, L. Quantification of neurotoxin BMAA (b-N-methylamino-L-alanine) in seafood from Swedish markets. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6931.

- Christensen, S.J.; Hemscheidt, T.K.; Trapido-Rosenthal, H.; Laws, E.A.; Bidigare, R.R. Detection and quantification of β-methylamino-L-alanine in aquatic invertebrates. Limnol. Oceanogr.-Method 2012, 10, 891–898.

- Salomonsson, M.L.; Fredriksson, E.; Alfjorden, A.; Hedeland, M.; Bondesson, U. Seafood sold in Sweden contains BMAA: A study of free and total concentrations with UHPLC–MS/MS and dansyl chloride derivatization. Toxicol. Rep. 2015, 2, 1473–1481.

- Salomonsson, M.L.; Hanssonab, A.; Bondesson, U. Development and in-house validation of a method for quantification of BMAA in mussels using dansyl chloride derivatization and ultra performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Methods-UK 2013, 18, 4865–4874.

- Field, N.C.; Metcalf, J.S.; Caller, T.A.; Banack, S.A.; Cox, P.A.; Stommel, E.W. Linking β-methylamino-L-alanine exposure to sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Annapolis, MD. Toxicon 2013, 70, 179–183.

- Banack, S.A.; Metcalf, J.S.; Bradley, W.G.; Cox, P.A. Detection of cyanobacterial neurotoxin β-N-methylamino-L-alanine within shellfish in the diet of an ALS patient in Florida. Toxicon 2014, 90, 167–173.

- Mondo, K.; Hammerschlag, N.; Basile, M.; Pablo, J.; Banack, S.A.; Mash, D.C. Cyanobacterial neurotoxin β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) in shark fins. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 509–520.

- Hammerschlag, N.; Davis, D.A.; Mondo, K.; Seely, M.S.; Murch, S.J.; Glover, W.B.; Divoll, T.; Evers, D.C.; Mash, D.C. Cyanobacterial neurotoxin BMAA and mercury in sharks. Toxins 2016, 8, 238.

- Mondo, K.; Broc Glover, W.; Murch, S.J.; Liu, G.; Cai, Y.; Davis, D.A.; Mash, D.C. Environmental neurotoxins β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) and mercury in shark cartilage dietary supplements. Food Chem. Toxicol 2014, 70, 26–32.

- Banack, S.A.; Cox, P.A. Biomagnification of cycad neurotoxins in flying foxes: Implications for ALS-PDC in Guam. Neurology 2003, 61, 387–389.

- Davis, D.A.; Mondo, K.; Stern, E.; Annor, A.M.; Murch, S.J.; Coyne, T.M.; Brand, L.M.; Niemeyer, M.E.; Sharp, S.; Bradley, W.G.; et al. Cyanobacterial neurotoxin BMAA and brain pathology in stranded dolphins. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213346.

- Pablo, J.; Banack, S.A.; Cox, P.A.; Johnson, T.E.; Papapetropoulos, S.; Bradley, W.G.; Buck, A.; Mash, D.C. Cyanobacterial neurotoxin BMAA in ALS and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2009, 120, 216–225.

- Downing, S.; Scott, L.L.; Zguna, N.; Downing, T.G. Human scalp hair as an indicator of exposure to the environmental toxin β-N-methylamino-l-alanine. Toxins 2018, 10, 14.

- Rosén, J.; Hellenäs, K.-E. Determination of the neurotoxin BMAA (β-N-methylamino-l-alanine) in cycad seed and cyanobacteria by LC-MS/MS (liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry). Analyst 2008, 12, 1785–1789.

- Courtier, A.; Potheret, D.; Giannoni, P. Environmental bacteria as triggers to brain disease: Possible mechanisms of toxicity and associated human risk. Life Sci. 2022, 304, 120689.

- Drobac, D.; Tokodi, N.; Simeunović, J.; Baltić, V.; Stanić, D.; Svirčev, Z. Human exposure to cyanotoxins and their effects on health. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol. 2013, 64, 119–130.

- Lance, E.; Arnich, N.; Maignien, T.; Biré, R. Occurrence of β-N-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) and isomers in aquatic environments and aquatic food sources for humans. Toxins 2018, 10, 83.

More