Over the past two centuries since its independence in 1847, Liberia has made significant progress in building an integrated public health system designed to serve its population. Despite a prolonged period of civil conflict (1990–2003) and the emergence of the 2014–2016 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) that crippled its already weakened health system, Liberia was able to re-emerge, making significant strides and gains in rebuilding and strengthening its health infrastructure and systems. Lessons learnt from the EVD epidemic have led to developments such as the newly established National Public Health Institute of Liberia (NPHIL) and several tertiary public health institutions to meet the growing demands of a skilled workforce equipped to combat existing and emerging health problems and/crisis, including informing the more recent COVID-19 response.

- Liberia

- public health

- Ebola virus disease

1. Introduction

2. Origins of Public Health in Liberia

2.1. Individuals That Pioneered Public Health

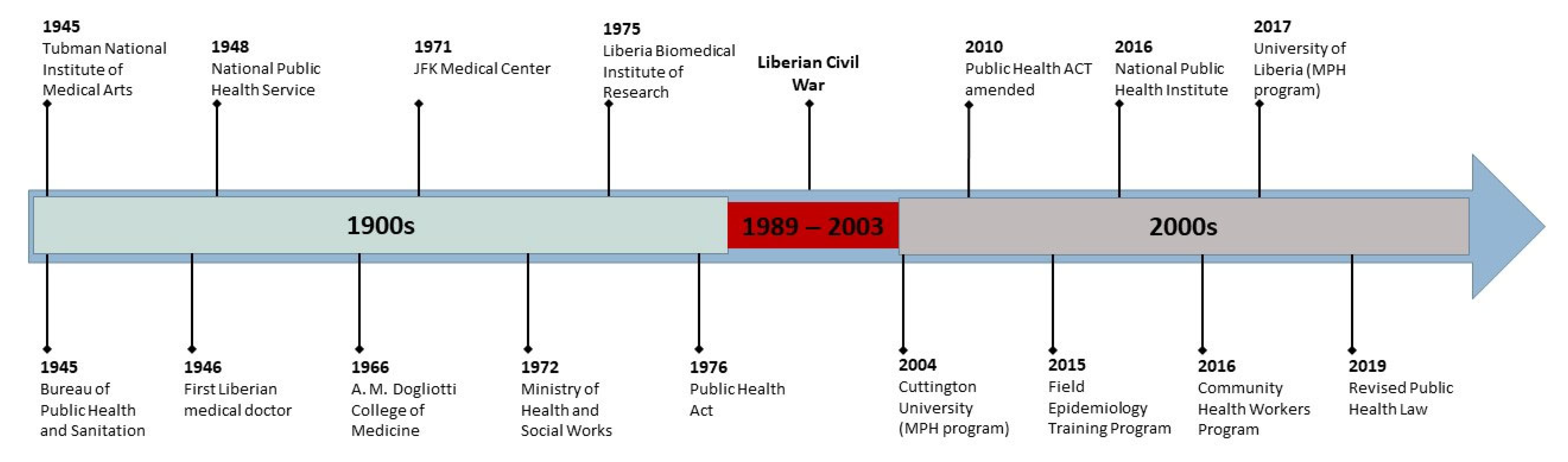

From its founding in 1847 till the early 1900s, Liberia’s health system consisted to a large extent of disjointed health facilities run by various Christian missionary led organizations and settlers from the United States. The early to mid-1900’s saw much advancement and progress being made in the fields of health system building and public health in Liberia [20][16]. In 1946, Dr. Joseph Nagbe Togba, M.D., returned home from the United States after completing his formal training and internship at Meharry Medical College. He was the first Liberian born physician to practice medicine in Liberia, where others prior to him were either white Americans or freed slaves who had settled in Liberia (Figure 1). Dr. Togba began his services in 1946 at the Liberian Government Hospital in Monrovia, as the only Liberian doctor and one of twelve physicians in the country. Upon arrival he wrote about his observations of public health in Liberia, “public health as practiced in Liberia simply applied to Monrovia and its environs. The work of public health was a matter of going along the streets to the homes of prominent officials in the cabinet, legislature, and judiciary. The grass and dirt around their homes were to be cleared. Garbage and dirt were not to be seen in certain places in Monrovia or else the Public Health team was to be taken to task” [20][16]. Towards the end of 1946, Dr. Togba was appointed Acting Director of Public Health and Sanitation by the government of Liberia. In 1949, Dr. Togba, received his master’s degree in Public Health from Harvard University, becoming the first Liberian doctor with a formal training in Public Health.

2.2. Early Public Health Institutions

In the early 1940s, President Tubman requested for American assistance to tackle the many health problems that the country confronted. In response, the U.S. State Department, in November 1944, directed the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) to send a small team of African American health workers to Liberia [20,32][16][18]. In 1945, the bureau of Public Health and Sanitation (Figure 1) was established in Monrovia, Liberia. The first policies on disease control and on health interventions for the fledgling country would emanate from this office [20][16]. This is considered by many as the cornerstone of public health and the national health system in Liberia. In 1946, shortly after Dr. Togba’s return home, the legislature passed the first ACT meant to impact the health of the public, which stipulated the following: there was to be an annual examination of all school children; there was to be premarital serology and medical examination with free treatment for those found positive; there was to be free treatment to all students and indigents in government clinics and hospitals. One of the earliest descriptions of the health system at the time was provided by Dr. John B. West who led the USPHS team. Dr. John B. West, wrote of his initial impression in the Public Health Reports, “we found that to the best of our knowledge there were six physicians, two dentists and an indeterminate number of nurses practicing in Liberia, which has a population estimated at two million” [32][18]. To prioritize public health and sanitation in and around the Monrovia, on 2 May 1945, President Tubman issued a proclamation that notified the residents to permit representatives of the USPHS mission to enter homes and spray or otherwise apply dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) to walls and ceilings for the purpose of killing mosquitos [20][16]. This could be considered one of the first large scale public health campaigns to be initiated in Liberia. In 1948, the Bureau of Public Health and Sanitation was dissolved and in its place was established the National Public Health Service (NPHS), led by Dr. Togba as the first Director General [20][16]. The NPHS would become the precursor to the present-day Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOH&SW). Dr. Togba went on to lead the Liberian delegation to the United Nations International Health Conference in New York in 1948 that culminated in the formation of the World Health Organization [20][16]. In 1950, Liberia’s appropriation for Public Health and Sanitation was 12% (10% in 2014) of its total revenues, which was one of the highest health appropriations in the world at the time [33][19].2.3. Key Institutions Involved in Workforce Development and Services

The mid 1900s saw the establishment of several key institutions meant to produce an essential healthcare workforce such as nurses, physician assistants, and medical doctors. By the late 1980s the Liberian health system was largely staffed by those trained in Liberian health institutions. The Tubman National Institute of Medical Arts (TNIMA) was established in 1945 through the effort and cooperation of the Liberian National Public Health services (now Ministry of Health and Social Welfare) and the United States Mission (Figure 1) [34,35][20][21]. In 1952, a training course of auxiliary health education was established at TNIMA through the effort of the Liberian American Joint Commission for Economic Development. Later that year, the Liberian requested WHO to establish a school of sanitation after realizing that most of the population’s common diseases were a result of poor sanitation and hygiene. The school was then established on a one-year training basis until 1961, when it was raised to two (2) years and renamed the School of Environmental Health. In 1964, the government of Liberia in collaboration with WHO and UNICEF established the Physician Assistant Program, and training started in March 1965 as a two (2) year program and increased to three (3) years in 1976. The Monrovia Torino Medical College was established in 1966 with the assistance of the Italian government, the Vatican, and the A. M. Dogliotti Foundation (Figure 1) [20,36][16][22]. The Catholic Church, under Pope Pius XII collaborated with the Italian government to build the physical structure of the medical college campus, which at the time included the academic building, a dormitory, an administrative office building and a teaching hospital, the St. Joseph Catholic Hospital. In 1970, the College was merged with the University of Liberia as the seventh academic program and the second professional school. It was then renamed The Achille Mario Dogliotti College of Medicine (A.M.D. College of Medicine) after the late Italian philanthropist and founder of the Dogliotti Foundation in Italy [20][16]. The A. M. Dogliotti College of Medicine was established to provide Liberia with medical doctors who were trained within the country and would help provide preventive and curative services across the health system. The first curriculum of the college laid a high emphasis on understanding core public health principles, which was seen to be essential for preparing young doctors who were expected to work in rural parts of Liberia. In 1968, with the publication of the Ten-Year Health Plan (1967–1976), there was a shift of emphasis from curative services to preventive medicine. The A.M.D College of Medicine played a critical role in providing trained physicians skilled in the principles of public health for a decentralized healthcare system. The Liberian Institute for Biomedical Research (LIBR) was established in the 1970s as a premier research facility to develop scientific breakthroughs for a variety of viral infections, including hepatitis B vaccines, and a safe blood sterilization process for blood transfusions (Figure 1) [30][23]. Currently, LIBR serves as the country’s reference laboratory and an integral component of the NPHIL, and the public health infrastructure in the country. The John F. Kennedy Medical Center (JFKMC) was established and opened on 18 June 1971 (Figure 1) [20,34,37][16][20][24]. This was a collaboration between the governments of Liberia and the United States of America [20,37][16][24]. The purpose of this institution was to improve medical education and extend preventive practices to the rural areas of Liberia as the center for training of doctors, nurses, midwives, laboratory technicians, and sanitarians. As such the west wing of the JFKMC was occupied by the Tubman National Institute of Medical Arts (TNIMA) classrooms, administrative offices, and library. By the late 1970s, the role of JFKMC as an integral part of the national health system was cemented as it became the national referral and teaching hospital. Today the JFKMC serves as the national teaching and referral hospital hosting both medical students and residents of the newly established Liberian College of Physicians and Surgeons.3. Key Events Impacting the Public Health System

3.1. The Liberian Civil War and Its Impact on the Health System

Before 1990, Liberia had focused primarily on curative and tertiary health care that had an urban bias. However, just before the war, there were signs that the MOH&SW had begun dealing with the twin issues of decentralization and provision of primary health care (PHC) services. It had acknowledged that it needed to move from the curative to the preventive and that it needed to empower its county health teams. A decade of civil war (1989–2003) devastated the health system and halted much progress made in the late 1900s [38,39,40,41,42,43][25][26][27][28][29][30]. At the war’s conclusion nearly 250,000 were dead, millions displaced; under-five mortality and maternal mortality were amongst the worst globally [44,45][31][32]. Of 293 public health facilities, 242 were destroyed, health educational/training institutions shut down, and only 10% of the population was estimated to have access to basic healthcare by the conflict’s end [42,43][29][30]. Some health facilities were not even staffed, and many lacked the reliable power supply, water, drugs, and equipment the most basic clinic should have. Achieving adequate staffing levels was particularly difficult—most skilled health workers had left during the war years and those left behind missed out on even a basic education, making it hard to find suitable candidates for fast-track training courses. By 1998, the total number of personnel working in the public sector had fallen from 3526 to 1396 [39,42,43,46][26][29][30][33]. In 2005, with donor support the government of Liberia embarked on a massive effort to rebuild the health system, prioritizing access to primary care, particularly in rural areas of the country. The emphasis on rural healthcare was a departure from the previously urban-centric focus of Liberia’s health sector. Additionally, postwar assessments of the health system identified an urgent need for national policy and service delivery guidelines to lead the revitalization of primary health care services. Prior to the war, Liberia had national policies that addressed only STDs/HIV/AIDS, EPI, control of diarrheal diseases, and malaria [39,42,43][26][29][30]. There were no official policies for family planning, non-communicable diseases, safe motherhood, acute respiratory infections, and drugs. Many of the country’s current health policies and guidelines were drafted in the period immediately following the end of the civil conflict. To address these varied challenges, Liberia’s post-war government chose to organize their reconstructive efforts around a Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) [39,42][26][29]. The BPHS is a defined set of evidence-based, cost-effective interventions that are considered essential to improve the health of the population [47,48,49,50][34][35][36][37].3.2. The Ebola Epidemic’s Influence on Public Health

Between 2014–2016, Liberia saw 10,678 cases and 4810 deaths from the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD), further disrupting service delivery across an already weak health system [2,51,52,53,54,55][2][38][39][40][41][42]. The Ebola epidemic revealed that health system strengthening requires a greater investment in all aspects of the health system (healthcare worker training, surveillance, reporting, analysis, policy, financing) and that post-conflict investments had focused primarily on primary health care and curative services at the cost of prevention [2,38,56,57,58][2][25][43][44][45].3.3. Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic

On 16 March 2020, the first case of COVID 19 was confirmed in Liberia [22][46]. This is significant given that the World Health Organization had only just declared COVID-19 a pandemic on the 11th of March, an indication of the country’s capacity and level of preparedness to identify cases and respond to this new health crisis [62][47]. In Liberia, to date (23 November 2022) there have been 8014 confirmed cases and 294 deaths; given its resources and capacity only a few years prior, the low number of fatalities is a formidable feat [63][48]. Liberia has used the many lessons learned from the 2014–2016 EVD epidemic when responding to the COVID-19 pandemic [22,46][33][46]. While healthcare service delivery, such as outpatients and noncommunicable disease clinics, were temporarily shut down, essential services, and healthcare worker training programs quickly adapted to meet the need for social distancing [22,64][46][49].4. Public Health as a Growing Field

4.1. Post Graduate Public Health Education

The period following the civil war and the 2016 EVD epidemic saw significant investments being made in the field of public health training. By 1998, the total public health personnel had fallen from 3526 to 1396, with the number of physicians declining to fewer than 30 [43,46][30][33]. According to a WHO 2021 report, there were 234 doctors, 9415 nurses/midwives, 1071 laboratory technicians, 3391 community health workers, and 4758 other health workers in Liberia [72,73][50][51]. Specialist physician and nurses were in critical need [10]. Several institutions of higher learning, including the NPHIL has prioritized training skilled public health practitioners to help meet the many health challenges that face the Liberian people today [38,46,59,66,74][25][33][52][53][54].4.2. Community Health Worker Program

In 2016, Liberia established a robust community health worker (CHW) program. A 2008 study found that only 15% of rural Liberians could access basic health services for childhood diseases such as diarrhea, malaria, measles, and malnutrition [40,42,80][27][29][55]. The Liberian government and partners agreed that the best way to address this gap in services was to use a cadre of community health workers (CHWs). Between 2016–2019, Liberia recruited, trained, and fielded 3177 CHW [80][55].4.3. Key Public Health Interventions, Policy, and Laws

The 2014–2016 Ebola epidemic served as a catalyst for the MOHSW. The need for universal access to safe and quality services through; a robust Health Emergency Risk Management System; and an enabling environment that restored trust in the health authorities‟ ability to provide services through community engagement in service delivery and utilization, improved leadership, governance, and accountability at all levels was seen as crucial [2,40,52,55,57,59,82][2][27][39][42][44][52][56]. In response to the need for a resilient and responsive health system, several key policies, plans and legislation was passed in the years following the Ebola epidemic.4.3.1. National Public Health Institute

After the devastating EVD epidemic, Liberia began to rebuild its health system. The need to strengthen Liberian expertise in infectious disease preparedness and response and in a host of other areas became obvious to policy and Ministry of Health leaders. The National Public Health Institute of Liberia was established by the Liberian government in December 2016 [30,76,84][23][57][58]. The Institute collaborates with and advises the Ministry of Health on infectious disease control, environmental health, occupational health and safety, and other issues. NPHIL is mandated to improve the public health status of the Liberian population in collaboration with relevant agencies and government institutions, in alignment with IHR core capacities (prevention, detection, and response to public health threats and events). It shall provide real-time surveillance and expert advice on public health morbidity and mortality to the Government of Liberia, key stakeholders, and the public. Public health workforce training and capacity building is an integral component of the Institute.4.3.2. Private Public Health Institutions

There are several non-governmental organizations both local and international that support public health interventions in Liberia [85][59]. One such local organization is the Public Health Initiative Liberia (PHIL) which was conceived in 2011 by Liberian health professionals to contribute towards the effectiveness of the health care delivery system of Liberia through leadership, partnership, innovation, advocacy, and empowerment. PHIL is a non-governmental organization registered in Liberia with a mission to promote and enhance Liberia’s quality of health care delivery through leadership, partnership, innovation, and capacity building [86][60]. Since its start, PHIL has been involved in various public health initiatives such as: cervical cancer screening, menstrual hygiene, breast cancer awareness, and community engagement during the Ebola epidemic and the current COVID-19 pandemic.4.3.3. Public Health Law

Liberia adopted its first public health law on 16 July 1976, and which stayed in effect for over forty years [84][58]. The 1976, law did not address new and emerging public health challenges such as emergency treatment, discrimination, mental health, regulation of marketing of products for infants and young children, zoonotic disease, non-communicable diseases, antimicrobial resistance, clinical trials, and alternative medicine [84][58]. In 2019, the 1976 public health law was revised to address these concerns and more. The Act to Establish the National Public Health Institute of Liberia that was approved on 27 December 2016 and states the NPHIL’s objective is to improve the health of the Liberian population in collaboration with relevant agencies and institutions of government.5. Conclusions

Over the past several decades Liberia has made significant progress, from rebuilding its healthcare system after a devastating civil war to strengthening its public health system post EVD epidemic, to being able to respond to the demands of new pandemics such as COVID-19. However, such progress can only be maintained at the present trajectory if serious considerations are given to continued prioritization by the government and sustained investments by the international community in the public health sector.References

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L.R.; Steffen, R. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010141.

- Wagenaar, B.H.; Augusto, O.; Beste, J.; Toomay, S.J.; Wickett, E.; Dunbar, N.; Bawo, L.; Wesseh, C.S. The 2014–2015 Ebola virus disease outbreak and primary healthcare delivery in Liberia: Time-series analyses for 2010–2016. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002508.

- Nikiforuk, A. The Fourth Horseman: A Short History of Epidemics, Plagues and Other Scourges; M. Evans: New York, NY, USA, 1991.

- UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Covid-19 and Hiv: 1 Moment 2 Epidemics. United Nations Joint Program on HIV AIDS; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Nkengasong, J. State of the Pandemic in Africa. Available online: https://africa.harvard.edu/event/covid-19-africa-featuring-dr-john-nkengasong-director-africa-cdc (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Bedford, J.; Farrar, J.; Ihekweazu, C.; Kang, G.; Koopmans, M.; Nkengasong, J. A new twenty-first century science for effective epidemic response. Nature 2019, 575, 130–136.

- Dawson, S.; Morris, Z. Future Public Health: Burden, Challenges and Opportunities; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009.

- Walker, B.J. The future of public health: The Institute of Medicine’s 1988 report. J. Public Health Policy 1989, 10, 19–31.

- Khan, M.S.; Dar, O.; Erondu, A.N.; Rahman-Shepherd, A.; Hollmann, L.; Ihekweazu, C.; Ukandu, O.; Agogo, E.; Ikram, A.; Rathore, T.R.; et al. Using critical information to strengthen pandemic preparedness: The role of national public health agencies. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002830.

- Pinto, R.M.; Park, S. COVID-19 Pandemic Disrupts HIV Continuum of Care and Prevention: Implications for Research and Practice Concerning Community-Based Organizations and Frontline Providers. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 2486–2489.

- Aranda, Z.; Binde, T.; Tashman, K.; Tadikonda, A.; Mawindo, B.; Maweu, D.; Boley, E.J.; Mphande, I.; Dumbuya, I.; Montaño, M.; et al. Disruptions in maternal health service use during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: Experiences from 37 health facilities in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e007247.

- Vogt, T.M.; Zhang, F.; Banks, M.; Black, C.; Arthur, B.; Kang, Y. Provision of Pediatric Immunization Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Assessment of Capacity Among Pediatric Immunization Providers Participating in the Vaccines for Children Program—United States, May 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 859–863.

- Blair, R.A.; Morse, B.S.; Tsai, L.L. Public health and public trust: Survey evidence from the Ebola Virus Disease epidemic in Liberia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 172, 89–97.

- Chung, H.; Downey, J.; Moskovitz, J.; Johar, S.; Leone, S. A systems approach to addressing Ebola. Columbia Univ. J. Glob. Health 2018, 8, 1–12.

- Tremblay, N.; Musa, E.; Cooper, C.; Van den Bergh, R.; Owiti, P.; Baller, A.; Siafa, T.; Woldeyohannes, D.; Shringarpure, K.; Gasasira, A. Infection prevention and control in health facilities in post-Ebola Liberia: Don’t forget the private sector! Public Health Action 2017, 7 (Suppl 1), S94–S99.

- Njoh, J. The Beginning and Growth of Modern Medicine in Liberia & the Founding of the John. F. Kennedy Medical Center, Liberia, 1st ed.; Panaf Publishing INC: Abuja, Nigeria, 2018.

- TLC Africa. Mrs. Rachel Emily Pearce Marshall. TLC Africa. 2022. Available online: https://www.tlcafrica2.com/death_marshall_rachel.htm (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- West, J.B. United States Health Missions in Liberia. Public Health Rep. 1948, 63, 1351–1364.

- Dunn, D.E. The Annual Messages of the Presidents of Liberia 1848–2010: State of the Nation Addresses to the National Legislature: From Joseph Jenkins Roberts to Ellen Johnson Sirleaf; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2011.

- TNIMA. Tubman National Institute of Medical Arts. 2022. Available online: https://jfkmc.gov.lr/tnima/ (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- TNIMA. Brief History of Tubman National Institute of Medical Arts. 2022. Available online: http://tnimaa.org/aboutus.html (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- University of Liberia. A. M. Dogliotti College of Health Life Science 2022. Available online: https://ul.edu.lr/a-m-dogliotti-college-of-health-life-science/ (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- NPHIL. National Public Health Institute 2022. Monrovia, Liberia. 2022. Available online: https://www.nphil.gov.lr/ (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- JFKMC. John, F. Kennedy Medical Center. Available online: https://jfkmc.gov.lr/ (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Bemah, P.; Baller, A.; Cooper, C.; Massaquoi, M.; Skrip, L.; Rude, J.M.; Twyman, A.; Moses, P.; Seifeldin, R.; Udhayashankar, K.; et al. Strengthening healthcare workforce capacity during and post Ebola outbreaks in Liberia: An innovative and effective approach to epidemic preparedness and response. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 33, 9.

- Lee, P.T.; Kruse, G.R.; Chan, B.T.; Massaquoi, M.B.; Panjabi, R.R.; Dahn, B.T.; Gwenigale, W.T. An analysis of Liberia’s 2007 national health policy: Lessons for health systems strengthening and chronic disease care in poor, post-conflict countries. Glob. Health 2011, 7, 37.

- Ling, E.J.; Larson, E.; Macauley, R.J.; Kodl, Y.; VandeBogert, B.; Baawo, S.; Kruk, M.E. Beyond the crisis: Did the Ebola epidemic improve resilience of Liberia’s health system? Health Policy Plan. 2017, 32, iii40–iii47.

- Kentoffio, K.; Kraemer, J.D.; Griffiths, T.; Kenny, A.; Panjabi, R.; Sechler, G.A.; Selinsky, S.; Siedner, M.J. Charting health system reconstruction in post-war Liberia: A comparison of rural vs. remote healthcare utilization. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 478.

- Kruk, M.E.; Rockers, P.C.; Williams, E.H.; Varpilah, S.T.; Macauley, R.; Saydee, G.; Galea, S. Availability of essential health services in post-conflict Liberia. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 527–534.

- Varpilah, S.T.; Safer, M.; Frenkel, E.; Baba, D.; Massaquoi, M.; Barrow, G. Rebuilding human resources for health: A case study from Liberia. Hum. Resour. Health 2011, 9, 11.

- World Bank Group. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. 2015. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/798471467987911213/pdf/100949-v2-P152335-PUBLIC-Box394828B-Trends-in-Maternal-Mortality-1990-to-2015-full-report.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- World Health Organization. Maternal Mortality: Level and Trends 2000 to 2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Dahn, B.; Kerr, L.; Nuthulaganti, T.; Massaquoi, M.; Subah, M.; Yaman, A.; Plyler, C.M.; Cancedda, C.; Marshall, R.E.; Marsh, R.H. Liberia’s first health workforce program strategy: Reflections and lessons learned. Ann. Glob Health 2021, 87, 95.

- Ministry of Health & Social Welfare (MoHSW) Republic of Liberia. National Health Policy and National Health Plan 2007–2011; Liberian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare: Monrovia, Liberia, 2007.

- Liberian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Basic Package of Health And Social Welfare Services; Ministry of Health and Social Welfare: Monrovia, Liberia, 2008.

- Ladner, J.T.; Wiley, M.; Mate, S.; Dudas, G.; Prieto, K.; Lovett, S.; Nagle, E.R.; Beitzel, B.; Gilbert, M.L.; Fakoli, L.; et al. Evolution and Spread of Ebola Virus in Liberia, 2014–2015. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 659–669.

- Shrivastava, S.R.; Shrivastava, P.S.; Ramasamy, J. Ebola-free Liberia: Scrutinizing the efforts of public health sector and international agencies. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 7, 1.

- Matanock, A.; Arwady, M.A.; Ayscue, P.; Forrester, J.D.; Gaddis, B.; Hunter, J.C.; Monroe, B.; Pillai, S.K.; Reed, C.; Schafer, I.J.; et al. Ebola Virus Disease Cases among Health Care Workers Not Working in Ebola Treatment Units-Liberia, June-August, 2014. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014, 63, 1077–1081.

- McQuilkin, P.A.; Udhayashankar, K.; Niescierenko, M.; Maranda, L. Health-care access during the Ebola virus epidemic in Liberia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 931–936.

- Arwady, M.A.; Bawo, L.; Hunter, J.C.; Massaquoi, M.; Matanock, A.; Dahn, B.; Ayscue, P.; Nyenswah, T.; Forrester, J.D.; Hensley, L.; et al. Evolution of ebola virus disease from exotic infection to global health priority, Liberia, mid-2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 578–584.

- Shoman, H.; Karafillakis, E.; Rawaf, S. The link between the West African Ebola outbreak and health systems in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone: A systematic review. Glob. Health 2017, 13, 1–22.

- Kanagasabai, U.; Enriquez, K.; Gelting, R.; Malpiedi, P.; Zayzay, C.; Kendor, J.; Fahnbulleh, S.; Cooper, C.; Gibson, W.; Brown, R.; et al. The Impact of Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Improvements on Hand Hygiene at Two Liberian Hospitals during the Recovery Phase of an Ebola Epidemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3409.

- Talbert-Slagle, K.; Koomson, F.; Candy, N.; Donato, S.; Whitney, J.; Plyler, C.; Allen, N.; Mourgkos, G.; Marsh, R.H.; Kerr, L.; et al. Health management workforce capacity-building in Liberia, post-ebola. Ann. Glob. Health 2021, 87.

- Ministry of Health and Government of Liberia. Investment Plan for Building a Resilient Health System in Liberia; Ministry of Health and Government of Liberia: Monrovia, Liberia, 2015.

- WHO. COVID-19 Timeline; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Marsh, R.H.; Plyler, C.; Miller, M.; Klar, R.; Adeiza, M.; Wachekwa, I.; Koomson, F.; Garlo, J.L., Jr.; Kruah, K.; Lake, S.C.; et al. Facing COVID-19 in Liberia: Adaptations of the resilient and responsive health systems initiative. Ann. Glob. Health 2021, 87.

- Adewuyi, A.P.; Amo-Addae, M.; Babalola, O.J.; Sesay, H.; Sanvee-Blebo, L.; Whesseh, F.; Akpan, G.E.; Umeokonkwo, C.D.; Nagbe, T. Innovative solution to admission process of Intermediate Field Epidemiology Training Program during COVID-19 Pandemic, Liberian Experience, 2021. J. Interv. Epidemiol. Public Health 2022, 5, 10.

- Fallah, M.P.; Reinhart, E. Apartheid logic in global health. Lancet 2022, 399, 902–903.

- Fallah, M.P.; Ali, S.H. When maximizing profit endangers our humanity: Vaccines and the enduring legacy of colonialism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stud. Political Econ. 2022, 103, 94–102.

- Lubogo, M.; Donewell, B.; Godbless, L.; Shabani, S.; Maeda, J.; Temba, H.; Malibiche, T.C.; Berhanu, N. Ebola virus disease outbreak; the role of field epidemiology training programme in the fight against the epidemic, Liberia, 2014. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2015, 22, 5.

- NPHIL. National Public Health Institute Strategic Plan. Monrovia, Liberia. 2018. Available online: https://www.nphil.gov.lr/ (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- WHO. Liberia COVID-19. COVID-19 Dashboard 2022; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Mutombo, P.N.; Fallah, M.P.; Munodawafa, D.; Kabel, A.; Houeto, D.; Goronga, T.; Mweemba, O.; Balance, G.; Onya, H.; Kamba, R.S.; et al. Misunderstanding poor adherence to COVID-19 vaccination in Africa–Authors’ reply. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e795.

- Pokuah Amo-Addae, M.; Adewuyi, P.A.; Nagbe, T.K. The Frontline Field Epidemiology Training Program in Liberia, 2015–2018 n.d. J. Interv. Epidemiol. Public Health 2020, 3, 1017.

- Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW), L. National Policy And Strategic Plan On Health Promotion 2016–2021; Ministry of Health: Monrovia, Liberia, 2016.

- Ministry of Health. National Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines; Ministry of Health and Child Care: Monrovia, Liberia, 2018.

- Fall, I.S. Ebola virus disease outbreak in liberia: Application of lessons learnt to disease surveillance and control. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 33, 19074.

- MOFA. The New Public Health Law as Revised; Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Monrovia, Liberia, 2019.

- NPHIL. In Proceedings of the Third Emmet Dennis National Scientific Conference, NPHIL. Monrovia, Liberia, 29–31 August 2022.

- Crossroads Global Hand. Public Health Initiative Liberia-PHIL. Available online: https://www.globalhand.org/en/browse/partnering/1/all/organisation/45391 (accessed on 9 December 2022).