Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 3 by Camila Xu.

The word Thymus comes from the Greek “thyo”, which means “offering” (to be burnt) and “perfume” because of the pleasant smell that the plant gives off naturally when burnt. T. algeriensis Boiss. and Reut. are classified in section Hyphodromi (A. Kerner) Haläcsy and subsection Subbracteati (Klokov) Jalas. It belongs to the order Lamiale, subfamily Nepetoideae, and tribe Menthae.

- Thymus algeriensis

- distribution

- botanical aspects

1. Thymus Genera: An Overview

The word Thymus comes from the Greek “thyo”, which means “offering” (to be burnt) and “perfume” because of the pleasant smell that the plant gives off naturally when burnt [1][2]. In ancient times, the Sumerians and Egyptians used it for embalming their dead (the mummification process). The Romans burned thyme to purify the air and keep pests away [3][4]. The name “Thyme” comes from the Greek word “Thymos” [5], meaning smell. In the Azores, Madeira and the western part of the Iberian Peninsula, Thyme has the Portuguese names “tomentelo” or “tormentelo”, “tomelo do pais”, “tomentelo do pais” or “tomilho” [2]. In the mountains of Ethiopia, it is known as “rausi”. Moreover, the African northwest has the following several Arabic vernacular names: “Djertil”, “Hamzoucha”, “Mezouqach”, and “Khieta”, and Berber names such as “Azoukni”, “Tazuknite”, “Rebba”, “Djouchchen”, and “Touchna” [6]. In Morocco, it is also called “azukenni” [2].

The genus Thymus, described by Carl Linnaeus in Species Plantarum, belongs to the monophyletic group of the subfamily Nepetoideae Kostel, the tribe Mentheae Dumort and the subtribe Menthinae Endl [7][8]. The species can be sub-shrubs or shrubs, often herbaceous above, usually gynodioic and aromatic. They grow spontaneously on dry, rocky slopes and in scrubland. The stems of species are generally ± quadrangular, hairy all round, on two opposite sides, or only on the corners. The leaves are small, entire, and frequently revolute and form compact, highly branched clumps that rise to about 20 cm above the ground [9]. They have inflorescences of whorls forming a terminal, condensed, often spiciform or interrupted thyrse [10]. These characteristics can have a high degree of polymorphism, demonstrating the complexity of the genus Thymus from a taxonomic and systematic point of view. Indeed, this hybridization has been observed between species belonging to different sections and between species with varying ploidy levels, resulting in different chemical compositions [2][11]. Eight sections can be distinguished in the genus from a taxonomic and geographical point of view, as follows: Micantes, Mastichina, Piperella, Teucrioides, Pseudothymbra, Thymus, Hyphodromi, and Serpyllum. Five of them (sections Micantes, Mastichina, Piperella, Pseudothymbra, and Teucrioides) are endemic to the West Mediterranean area (Iberian Peninsula, Northwest Africa) [12].

2. Thymus algeriensis Boiss. and Reut.

2.1. Distribution

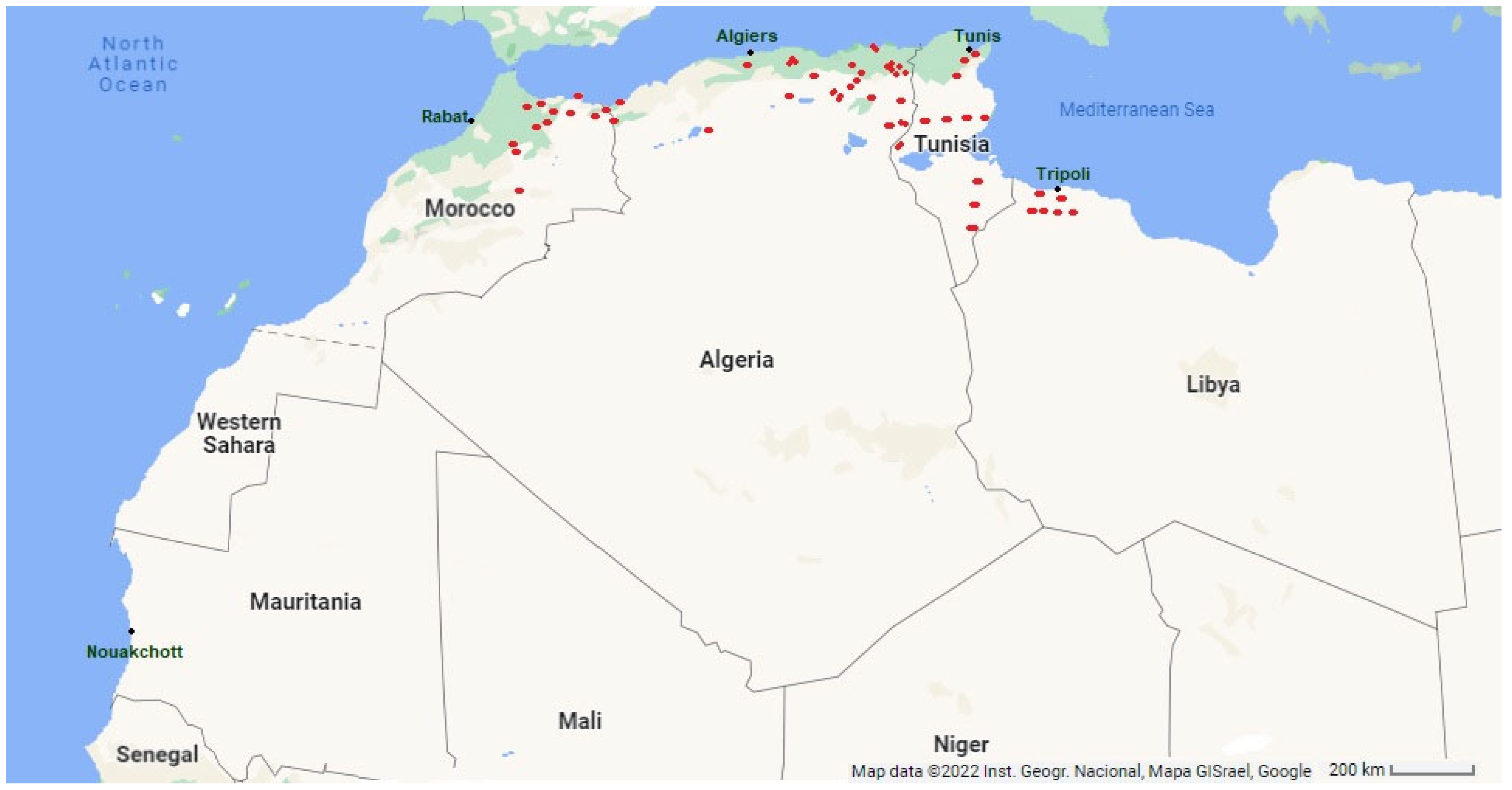

The medicinal properties of Thymus species have been investigated in numerous scientific studies, including in vitro et in vivo experiments. The results reveal that they have a unique combination of beneficial functions due to the Mediterranean climate [13][14][15]. In this geographical area, the western Mediterranean, under the influence of the Atlantic Ocean, the climatic conditions are favorable for thyme vegetation. Therefore, they are mainly found on the Mediterranean coast [16]. Thymus species are sun-loving, heliophilous plants, a fact that reflects the ecology of the genus. Thymus plants frequently live on rocks or stones, and the soil must be well-drained [8]. They need very different substrates. T. algeriensis usually lives on calcareous soils, characteristic of the Maghreb [17]. The Algerian species are found in the eastern Tell, in the bedrock areas, and on the high mountain plateaus up to the border of the pre-Sahara Tassili [18][19]. They are mainly present in subhumid and arid zones from the North-East of Algeria to the Tunisian border [9]; a few isolated individuals occur in Mascara province and from the Oran region to the Moroccan borders (Figure 1).

Figure 1. In Red Thymus algeriensis Boiss. and Reut. Maghreb distribution (Coordinates N26° 14.526120 E5° 9.313440) [18].

2.2. Systematic Classification and Botanical Aspects

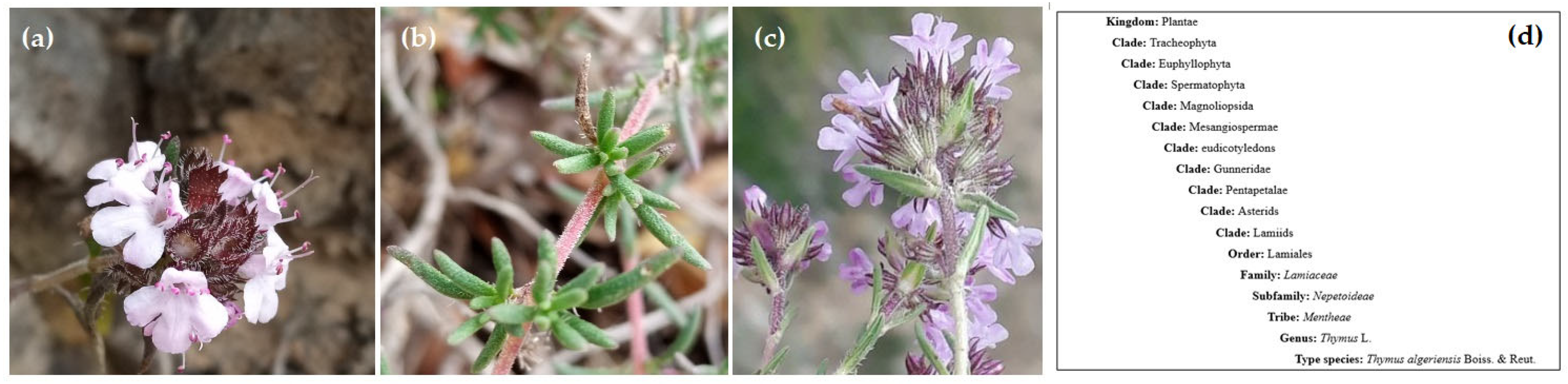

According to Morales [2], T. algeriensis Boiss. and Reut. are classified in section Hyphodromi (A. Kerner) Haläcsy and subsection Subbracteati (Klokov) Jalas [21][22]. It belongs to the order Lamiale, subfamily Nepetoideae, and tribe Menthae (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Systematic classification and botanical aspects of Thymus algeriensis Boiss. and Reut flowers and leaves. (a,b) from Tunisia, (c) from Algeria, (d) Systematic classification of T. algeriensis [23].

2.3. Uses in Folk Medecine

In traditional Algerian medicine, T. algeriensis has been used as an astringent, expectorant, and healing agent and a blood circulation stimulant and aphrodisiac [28][29]. Infusion, decoction, and powder of the aerial parts are used in Naâma, southwest Algeria for treating colds as an anti-inflammatory, to manage hypercholesterolemia and menstrual cycle problems, and recently against COVID-19 [30]. El Kantara’s area (Algerian Sahara gate) is traditionally employed to flavor coffee, buttermilk, and tea. Infusing leaves and flowers are used against abdominal stomach pain, wound infections, and food poisoning. It is also antihypertensive and manages heart diseases [31]. In Morocco, T. algeriensis is a medicinal species indicated in the traditional treatment of diabetes [32]. It is a tonic stimulant against cough, fever, and wound infections [33][34]. It also treats asthma, bad breath, chest pain, lung disorders, and rhinosinusitis. In addition, some of his by-products were used as antitussives [35] and anti-inflammatory agents by topical or oral administration [36][37][38]. Traditionally in Tunisia, T. algeriensis is used as a culinary herb, fresh or dried [39], or as condiments or flavoring mainly added to black tea [40]. It is widely used in popular Tunisian medicine as a protective treatment against digestive tract diseases and abortion [41].References

- Rey, C. Selection of Thyme for extreme areas (of Switzerland). Acta Hortic. 1992, 306, 66–70.

- Morales, R. The History, Botany and Taxonomy of the Genus Thymus. In Thyme the Genus Thymus; Stahl-Biskup, E., Saez, F., Eds.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2002; pp. 1–43.

- Anne, M. Healing with Flowers: The Power of Floral Medicine; Aeon Books: London, UK, 2022; p. 488. ISBN 9781913504793.

- Evelyn, K. Thyme & Oregano, Healing and Cooking Herbs, and More than 30 Ways to Use Them; Kindle: Athens, Greece, 2014; ISBN 9781312662186.

- Richard, H.; Benjilali, B.; Banquour, N.; Baritaux, O. Etude de diverses huiles essentielles de Thym du Maroc—Institut National de Recherche En Agriculture, Alimentation et Environnement. Lebensm-Wiss.+ Technol. 1985, 18, 105–110.

- Beloued, A. Plantes Médicinales d’Algérie; Offices Des Publications Universitaires: Ben Aknoun, Algeria, 2005; ISBN 9789961003046.

- Harley, R.M.; Atkins, S.; Budantsev, A.L.; Cantino, P.D.; Conn, B.J.; Grayer, R.; Harley, M.M.; De Tok, R.; Krestovskaja, T.; Morales, R.; et al. Labiatae. In VII Flowering Plants Dicotyledons, Lamiales (Except Acanthaceae Including Avicenniaceae); Kadereit, J., Ed.; The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 6, pp. 167–275.

- Morales, R. Synopsis of the Genus Thymus L. in Mediterranean area. Lagascalia 1997, 19, 249–262.

- Quézel, P.; Santa, S. Nouvelle Flore de l’Algérie et des Régions Désertiques Méridionales; CNRS: France, Paris, 1962; Volume 2, pp. 565–1170.

- Kew Science Thymus, L. Plants of the World Online. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:30002942-2 (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Karaca, M.; İnce, A.G.; Aydin, A.; Elmasulu, S.Y.; Turgut, K. Microsatellites for genetic and taxonomic research on Thyme (Thymus L.). Turk. J. Biol. 2015, 39, 147–159.

- Bartolucci, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Passalacqua, N. Typification of names and taxonomic notes within the genus Thymus L. (Lamiaceae). Taxon 2013, 62, 1308–1314.

- Bower, A.; Marquez, S.; de Mejia, E.G. The health benefits of selected culinary herbs and spices found in the traditional Mediterranean Diet. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 2728–2746.

- Amrouche, T.A.; Yang, X.; Capanoglu, E.; Huang, W.; Chen, Q.; Wu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, B. Contribution of edible flowers to the Mediterranean diet: Phytonutrients, bioactivity evaluation and applications. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1–39.

- Nieto, G. A Review on applications and uses of Thymus in the food industry. Plants 2020, 9, 961.

- Sánchez-Mata, D.; Morales, R. Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants; Sánchez-Mata, M., Tardío, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 15–31.

- Tassin, C. Paysages Végétaux du Domaine Méditerranéen: Bassin Méditerranéen, Californie, Chili Central, Afrique du Sud, Australie Méridionale; IRD (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement): Paris, France, 2012; p. 1135. ISBN -10 2709917319.

- African Plant Database. Available online: https://africanplantdatabase.ch/en/nomen/145270 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Eflora Maghreb Thymus Algeriensis Boiss. & Reut. Available online: https://efloramaghreb.org/specie/145270 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- El Ajjouri, M.; Ghanmi, M.; Satrani, B.; Amarti, F.; Rahouti, M.; Aafi, A.; Rachid Ismaili, M.; Farah, A. Composition chimique et activité antifongique des huiles essentielles de Thymus Algeriensis Boiss. & Reut. et Thymus Ciliatus (Desf.) Benth. contre les champignons de pourriture du bois. Acta Bot. Gall. 2010, 157, 285–294.

- Morales, R. Studies on the genus Thymus. Lamiales Newsl. 1996, 4, 6–8.

- Stahl-Biskup, E.; Sáez, F. Thyme: The Genus Thymus, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; ISBN 9780429218651.

- INaturalist Site, Species Observed in Algeria and Tunisia by Larbi Afoutni and Khaled Bessrour, Occurrence 3455238505. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/3455238505 (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Ali, I.B.E.H.; Zaouali, Y.; Bejaoui, A.; Boussaid, M. Variation of the chemical composition of essential oils in Tunisian populations of Thymus Algeriensis Boiss. et Reut. (Lamiaceae) and implication for conservation. Chem. Biodivers. 2010, 7, 1276–1289.

- Tarayre, M.; Thompson, J.D. Population genetic structure of the Gynodioecious Thymus vulgaris L. (Labiatae) in Southern France. J. Evol. Biol. 1997, 10, 157–174.

- Ben El Hadj Ali, I.; Guetat, A.; Boussaid, M. Chemical and genetic variability of Thymus Algeriensis Boiss. et Reut. (Lamiaceae), a North African endemic species. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 40, 277–284.

- Guesmi, F.; Saidi, I.; Bouzenna, H.; Hfaiedh, N.; Landoulsi, A. Phytocompound variability, antioxidant and an-tibacterial activities, anatomical features of glandular and aglandular hairs of Thymus hirtus Willd. ssp. algeriensis Boiss. and Reut. over developmental stages. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 127, 234–243.

- Baba Aïssa, F. Les Plantes Medicinales en Algerie; Bouchéne-ad Diwan: Algiers, Algeria, 1991.

- Benkiniouar, R.; Rhouati, S.; Touil, A.; Seguin, E.; Chosson, E. Flavonoids from Thymus algeriensis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2007, 43, 321–322.

- Bouafia, M.; Amamou, F.; Gherib, M.; Benaissa, M.; Azzi, R.; Nemmiche, S. Ethnobotanical and ethnomedicinal analysis of wild medicinal plants traditionally used in Naâma, Southwest Algeria. Vegetos 2021, 34, 654–662.

- Mechaala, S.; Bouatrous, Y.; Adouane, S. Traditional knowledge and diversity of Wild medicinal plants in El Kantara’s Area (Algerian Sahara Gate): An ethnobotany survey. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 33–45.

- Hachi, M.; Ouafae, B.; Hachi, T.; Mohamed, E.B.; Imane, B.; Atmane, R.; Zidane, L. Contribution to ethnobotanical study of antidiabetic medicinal plants of the central middle Atlas region (Morocco). Lazaroa 2016, 37, 135–144.

- Sijelmassi, A. Les Plantes Médicinales du Maroc; Le Fennec: Casablanca, Maroco, 1993; Volume 1, p. 285. ISBN -10 9981838020.

- Bellakhdar, J. Pharmacopée Marocaine traditionnelle: Médecine Arabe Ancienne et Savoirs Populaires; Paris Ibiss Press: Paris, France, 1997; p. 766.

- Fakchich, J.; Elachouri, M. An overview on ethnobotanico-pharmacological studies carried out in Morocco, from 1991 to 2015: Systematic review (part 1). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 267, 113200.

- Ismaili, H.; Milella, L.; Fkih-Tetouani, S.; Ilidrissi, A.; Camporese, A.; Sosa, S.; Altinier, G.; della Loggia, R.; Aquino, R. In Vivo topical anti-inflammatory and in vitro antioxidant activities of two extracts of Thymus satureioides Leaves. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 91, 31–36.

- Ismaili, H.; Sosa, S.; Brkic, D.; Fkih-Tetouani, S.; Ilidrissi, A.; Touati, D.; Aquino, R.P.; Tubaro, A. Topical antiinflammatory activity of extracts and compounds from Thymus broussonettii. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2002, 54, 1137–1140.

- Ismaili, H.; Tortora, S.; Sosa, S.; Fkih-Tetouani, S.; Ilidrissi, A.; Della Loggia, R.; Tubaro, A.; Aquino, R. Topical Anti-inflammatory activity of Thymus willdenowii. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2001, 53, 1645–1652.

- Pottier-Alapetite, G.A. Flore de la Tunisie: Angiosperme–Dicotylédones: Gamopétales; Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique et le Ministère de l’Agriculture: Tunis, Tunisia, 1981; Volume 2.

- Karous, O.; Jilani, I.B.H.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z. Ethnobotanical study on plant used by semi-nomad descendants’ community in Ouled Dabbeb-Southern Tunisia. Plants 2021, 10, 642.

- Le Floc’h, É. Contribution à une Étude Ethnobotanique de la Flore Tunisienne; Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique: Tunis, Tunisia, 1983.

More