Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Sunila Mahavadi and Version 2 by Catherine Yang.

The G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) is receiving attention for its role in disease pathogenesis and treatment outcomes. GPER expression patterns in various cancers are highly complex and now debatable, with some cancers showing upregulated GPER expression patterns and others showing downregulated or even inconclusive GPER expression patterns. GPER, for example, is overexpressed in seminomas, melanomas, some ovarian cancers, lung cancers (NSCLC), insulin-resistant endometrial cancer models, and the vast majority of breast cancer models (particularly triple negative breast cancer, TNBC).

- G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor

- biosignaling

- therapeutics

1. GPER in Testicular Germ Cell Cancer

Testicular germ cell cancer (TGCC), the most common solid cancer among young men, expresses both classical (ERβ) and non-classical (GPER/GPR30) estrogen receptors [1][58]. GPER is often overexpressed in seminomas but not in non-seminomas [1][2][58,59]; this overexpression tends to stimulate seminoma cell proliferation by activating ERK1/2 and protein kinase A. An in vitro analysis using JKT-1 cell lines (derived from a human testicular seminoma) revealed that the binding of endocrine disruptors (EDCs) such as bisphenol A (at a low concentration) to GPER induces seminoma cell proliferation [3][4][60,61]. Estradiol-17β conjugated to bovine serum albumin has been reported to stimulate JKT-1 cell proliferation via activation of the PKA pathway with rapid phosphorylation of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) through GPER [3][60]. Further, in TCam-2 seminoma cell line, estradiol, acting through GPER-cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling, induces ERα36 isoform expression, in TCam-2 seminoma cell line, leading to increased cell proliferation [5][62]. GPER overexpression in human testicular seminomas is associated with ERβ downregulation, causing a switch in estrogen responsiveness [6][63]. In the TCam-2 cell line, 17β-estradiol induces the activation of ERK1/2 and increases c-Fos expression through the GPER-associated ERβ downregulation. According to a cohort study, there is a genotype-phenotype association between GPER SNPs and seminomas [2][59]. Two of these SNPs (SNP rs3808350 located in the 5′-regulatory region and SNP rs3808351 in the 5′-untranslated region) located in the promoter region of the GPER gene allow them to modify the gene’s expression pattern [2][59], as evident in overexpression of GPER previously reported for TGCC [1][3][7][58,60,64]. Thus, a better understanding of the role of GPER in tumorigenesis of TGCC would open perspectives to identify new therapeutic targets.

2. GPER in Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is a complex disease for which a plethora of factors contribute to alterations that favor the initiation and progression of the disease [8][65]. Although estrogen-associated signaling has been associated with canonical ER-α and ER-β signaling, current research is focusing on the role of GPER downstream signaling in breast cancer pathogenesis and response to therapy [9][66]. GPER is expressed in breast cancer tissues with an abundance of about 50–60%. Activated GPER activates signaling proteins, including the EGFR, phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K), mitogen-activated protein kinases and focal adhesion kinase along with other proteins linked to the regulation of cell growth and division [10][67].

Due to variations in the pathophysiology and treatment of the different breast cancer subtypes, studies have broadly examined GPER expression in ER-positive and ER-negative subtypes [11][68]. For patients, GPER expression correlated with estrogen and progesterone receptor status and poor response to therapy [12][69]. For ER-positive breast cancer patients, GPER expression is associated with tamoxifen resistance and lower survival rates [13][10]. GPER activation and downstream signaling increases the expression and membrane localization of ATP- binding cassette subfamily G member 2 (ABCG2), which is implicated in multi-drug resistance; inhibition or knockdown of GPER attenuated these effects [9][66]. However, GPER activation by G-1 reduced cell proliferation, induced cell cycle arrest at M-phase, and enhanced apoptosis in MCF-7 ER-positive breast cancer cells [14][70]. The authors suggested that GPER activity could be affected by epigenetic factors, as GPER expression was inactivated by promoter methylation.

In triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), GPER expression is increased and GPER-mediated signaling contributes to TNBC invasiveness, metastasis, and recurrence through mechanisms involving the activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), which mediates alterations in expression of target genes [10][67]. Experiments with the MDA-MB-231 TNBC cell line showed that in the presence of bisphenol A, a GPER ligand, there was increased GPER expression and activation of FAK and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (ERK2), which mediate invasiveness and metastasis in TNBC [15][71]. The role of GPER in TNBC proliferation was deduced from a study that examined the interaction of GPER and Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 1 (NHERF1) on the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells [16][72]. The interaction of NHERF1 with GPER inhibited GPER-mediated activation of ERK1/2 and suppressed the proliferation of TNBC cells [16][72]. In TNBC cells treated for 96 h with 200 nMgefitinib, an inhibitor of EGFR that is transactivated by GPER, there were downregulation of GPER and suppressed cell proliferation [17][73].

In contrast, GPER expression is protective in TNBC, as MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumors treated with the GPER agonist G1 showed inhibited angiogenesis and metastasis via mechanisms involving the inhibition of NF-kB and IL-6 signaling [18][11]. Additionally, MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 TNBC cells treated with the G-1 agonist for GPER activation showed inhibited cell growth via mechanisms involving induction of cell cycle arrest at G2/M and increased caspase-3 mediated apoptosis [14][70]. For MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells, GPER activation reduced their proliferation and invasiveness of the cells [19][74]. Clinical studies with 135 Chinese TNBC patients found that GPER expression, determined by immunohistochemistry, positively correlated with favorable treatment outcomes and negatively correlated with lymph node metastasis [20][75]. A similar study accomplished in the United Kingdom involving 1,245 primary invasive breast cancer patients found that high GPER expression was associated with smaller tumors and lower tumor grades [21][76]. However, the study did not report on the ER status of the patients.

2.1. GPER Localization and Predisposition to Breast Cancer Subtype

Although the expression and localization of GPER has long been debated, several studies have revealed that, in breast cancer cells, GPER is detectable both on the surface of the cell membrane and intracellularly within the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus [22][23][77,78]. A study revealed a predominant cytoplasmic GPER expression in 189 primary invasive breast carcinomas (19.3%); a predominant nuclear GPER expression was observed in 529 cases (53.9%) [24][79]. Using murine knockout models, GPER overexpression and localization in the plasma membrane have been shown to be essential events for breast cancer progression [25][80]; its absence in the plasma membrane has been reported to have an excellent long-term prognosis for ERα+ breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen [23][78]. The plasma membrane localization of GPER is associated with an increased risk of death for metachronous contralateral breast cancer [26][81]. Additionally, plasma membrane-localized GPER correlates with poor prognostic markers such as high Ki67 and a triple-negative subtype. Additionally, GPER found within the endoplasmic reticulum likely contributes to normal estrogen physiology as well as pathophysiology due to its specific binding to estrogen, resulting in intracellular calcium mobilization in the nucleus [27][82]. Furthermore, cytoplasmic GPER expression in breast carcinomas is associated with non-ductal histological subtypes, better histological differentiation, luminal A and B subtypes, low tumor stages, and a better clinical outcome [24][79]. In contrast, the expression of nuclear GPER in breast carcinomas is associated with triple-negative subtypes with less favorable clinical outcomes [24][79]. In estrogen-stimulated, breast cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), there is a peculiar GPER translocation to the nucleus where it targets genes such as c-FOS and CTGF leading to increased expression of these genes [28][83]. A P16L polymorphism present in CAFs affects the N-glycosylation status of GPER, which promotes its nuclear localization [29][84]. This alternate subcellular localization of GPER in CAFs and potentially in the carcinoma cells themselves may modify the action of these cells and affect tumor progression [29][84]. Tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7 breast cancer cells maintain a proliferative response to estrogen by promoting the translocation of GPER to the cell membrane as well as it signaling [11][68]. Moreover, long-term tamoxifen treatment has been reported to facilitates the translocation of GPER to cell membranes, resulting in abnormal activation of the EGFR/ERK signaling pathway, which enhances communications between tumor cells and their microenvironment [30][85]. This reveals that GPER subcellular localization influences its function in the progression and prognosis of breast carcinomas.

2.2. GPER Target Genes in the Progression of Breast Cancer Malignancies

Estrogenic effects have been ascribed to the nuclear estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), which function as transcription factors binding to the regulatory response elements in the promoters of target genes [31][86]. However, estrogen also triggers non-genomic, rapid cellular events through a seven-transmembrane GPER referred to as GPR30 [32][87]. GPER is expressed both in the plasma membrane and in the endoplasmic reticulum [26][81]. It is involved in the proliferation, migration, chemoresistance, and metastasis of breast cancer [33][88]. The binding of estrogen and related compounds to GPER activates multiple intracellular signaling pathways, including the MAPK, adenylyl cyclase, and PI3K signaling pathways through transactivation of the (EGFR) [34][89]. Therefore, GPER is required for EGFR and ERK activation by epidermal growth factor [35][90]. It is noteworthy that GPER nongenomic signaling events can result in long-term transcriptional changes and a broad range of responses among a variety of cell types [2][59].

In a study by Filardo et al., 17β-estradiol (E2)-triggered rapid activation of ERK1/2 in breast cancer cells that correlated with GPER expression [36][91]. It was demonstrated that GPER-dependent ERK activation occurred via transactivation of the EGFR through matrix metalloproteinase activity and integrin α5β1, which triggered the extracellular release of heparan-bound epidermal growth factor (HB-EGF) [37][92]. Cellular signaling resulting in GPER activation leads to ERK1/2 phosphorylation [38][93]. A study by Pupo et al. confirmed that ERK1/2 phosphorylation by bisphenol A was abolished by silencing GPER expression, suggesting that GPER is required for ERK1/2 activation [39][94]. ERK1/2 has multiple substrates such as transcriptional regulators and steroid hormone receptors, which mediate several biological processes, such as migration, proliferation, angiogenesis, and invasion [40][95]. In mammary tumors, ERK1/2 substrates are mostly hyperactivated because of the high mutation rate of approximately 30% in ERK1/2 members. Pupo’s findings further revealed that bisphenol A transactivates the promoter sequence of c-FOS, early growth response 1 (EGR-1), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and hence stimulated mRNA expression of these genes and increased their protein levels [39][94].

GPER mediates the transactivation of the EGFR to the MAPK signaling axis in response to E2 [36][91]., GPER is associated with the modulation of calcium (Ca2+), cAMP, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) [41][96]. GPER-triggered rapid signaling events have been determined to regulate gene expression of BCL2 and cyclin D1 [42][97], and EGR-1 [43][44][98,99]. Madeo and Maggiolini [43][98] revealed that GPER is exclusively expressed as an estrogen receptor in mammary cancer-associated fibroblasts and induces the expression of C-FOS, cyclin D1, and CTGF in response to E2, as confirmed at both the mRNA and the protein levels, resulting in the promotion of proliferation. In response to estrogen, GPER is recruited to chromatin at target genes such as c-FOS, PI3K, Src, FAK, BCL2, cyclin D1, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), and early growth response 1 (EGR1) [43][45][98,100]. Overexpression of Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src kinases has been observed in breast cancer cell lines and tumors. In MDA-MB-231 cells, bisphenol A activates FAK, Src, and ERK2 via GPER in MDA-MB-231 cells [46][101]. Bisphenol A also stimulates AP-1 and NF-κB-DNA binding via an Src and ERK2-dependent pathway. Src family kinases regulate cell cycle progression, growth, survival, and migration. Src has been associated with EGFR transactivation via phosphorylation at specific tyrosine residues. FAK and Src regulate cell motility, an important component of focal adhesion and cell migration. Breast tumors and cell lines have increased activity of src kinases and FAK, which are associated with tumor growth and metastasis [45][100]. E2 and GPER selective agonist G1 activates FAK, ERK2, and Akt1 via GPER in TNBC MDA-MB-231 and TNBC SUM-159 cells [10][67]. E2 and tamoxifen activate FAK and cause migration in endometrial cancer cells via GPER [47][102]. FAK is a 125 kDa protein tyrosine kinase that is found in focal adhesion, and is involved in a variety of biological processes such as spreading, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion, survival, and angiogenesis [48][103].

In breast cancer-associated fibroblasts, the GPER agonist G1 induced CYP19A1 gene expression and increased E2 production via the GPER/EGFR/ERK pathway which in turn promoted proliferation and cell-cycle progression [49][104]. In mammary CAFs, GPER/EGFR/ERK signaling has been claimed to upregulate the expression of EGR1, CTGF, C-FOS, and cyclin D1, resulting in proliferation enhancement in mammary CAFs [39][44][94,99]. Bisphenol A to stimulates the proliferation and migration of SKBR3 cells and carcinoma-associated fibroblast (CAFs) through GPER [39][94]. Growth factors including EGF, CTGF, transforming growth factor a/b, and insulin-like growth factor to regulate GPER expression and are regulated by GPER activation [43][50][98,105]. GPER expression correlates with upregulation of aromatase gene (an enzyme involved in estrogen synthesis) upregulation [39][51][94,106].

A well-recognized GPER agonist, genistein, increases breast cancer-associated aromatase expression and activity in vitro [51][106]. Moreover, in MCF-7R cells, GPER/EGFR/ERK signaling upregulates β1-integrin expression and activates downstream kinases, which contributes to cancer-associated fibroblast-induced cell migration and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition [52][107] (Table 2). Integrins are focal adhesion receptors that mediate adhesion between the actin cytoskeleton and the extracellular matrix, with various components, including scaffolding proteins, GTPases, kinases, and phosphatases [53][114]. Integrins mediate signal transduction between the tumor cell and its microenvironment and β1-integrin and coordinates some cellular processes such as inflammation, proliferation, adhesion, and invasion [54][115]. Hypoxia upregulates CTGF expression in a HIF-1α-dependent manner; however, GPER expression is required for the HIF-1α-mediated induction of CTGF by hypoxia [55][108]. CTGF primarily modulates and coordinates signaling responses involving components of the extracellular matrix [42][97].

Activation of GPER by its specific agonist significantly inhibits interleukin-6 (Ile-6) and vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) by suppressing NF-κB binding to the Ile-6 gene promoter. Proangiogenic factors including Ile6 and Ile8 are highly expressed and necessary in the growth of triple-negative cancer cells [56][116]. These proteins activate quiescent microvascular endothelial cells and induce them to form tube structures [57][117]. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a chemoattractant and proliferative cytokine that initiates angiogenesis in tumor development [20][75]. E2 and the GPER-selective ligand G-1 triggered a GPER/EGFR/ERK/c-fos signaling pathway that leads to increased VEGF via upregulation of HIF1α [58][110]. In a mouse xenograft model of breast cancer that ligand activated GPER can enhanced tumor growth and the expression of HIF1α, VEGF, and the endothelial marker CD34 [58][110]. In addition, a mechanistic study revealed that E2-mediated GPER activation upregulated HOTAIR (lncRNAs highly expressed in primary breast tumors) gene expression in the TNBC cell lines (MDA-MB-231 and BT549) as well as in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and cancer tissues from breast cancer patients through the suppression of miR-148a [59][111]. Therefore, HOTAIR could be viewed as a potential therapeutic target in breast cancer; and its level in primary tumors is a powerful predictor of metastases and death [59][111]. GPER stimulation activates yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) and transcriptional coactivator with a PDZ-binding domain (TAZ), two homologous transcription coactivators and key effectors of the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway, via the Gαq-11, PLCβ/PKC, and Rho/ROCK signaling pathways. TAZ is required for GPER-induced gene transcription, breast cancer cell proliferation, migration, and tumor growth [60][118]. Chrysin-NPs inhibit the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells via induction of GPER expression, and this action suppresses matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and NF-kB expression [61][119]. In breast cancer, the expression levels of MMPs are higher than in normal breast tissues. MMPs are key enzymes responsible for ECM breakdown and are involved in the regulation of cell growth, migration, angiogenesis, and invasion [62][120]. A study using breast SkBr3, colorectal LoVo, hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cancer cells, and breast cancer-associated fibroblasts suggested that GPER is involved in regulating fatty acid synthase (FASN) expression and activity in cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts, which contributes to cancer progression [63][112]. FASN is needed in cancer cells for synthesis of fatty acids, which in turn are used for energy production, cellular membranes, signaling molecules, and membrane protein anchors [64][121]. In SkBr3 cancer cells and CAFs, miR-338-3p suppresses gene expression and proliferative effects induced by E2 through GPER. miR-338-3p is involved in cancer development through inhibition of the expression of certain genes at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [65][122]. For SkBr3 breast cancer and HepG2 hepatocarcinoma cells, E2 and the selective GPER ligand G-1 induce miR144 expression and downregulate the onco-suppressor Runx1 through GPER [66][113].

3. GPER in Lung Cancer

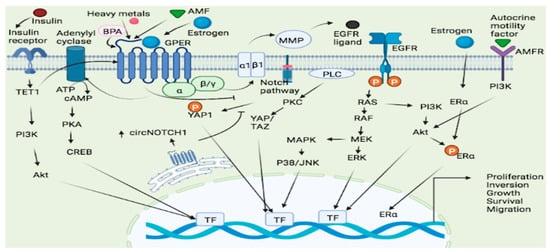

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death worldwide and the second most frequent cancer and the major cause of cancer death in the United States [67][123]. Gene expression studies reveal that the expression of GPER is considerably greater in human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines (NSCLC) as compared to normal lung cells [68][124]. This receptor appears to promote NSCLC cell proliferation by modulating the circ-NOTCH1/YAP1/QKI/ /m6A methylated NOTCH1 pathway, and in this way, the GPER upregulates circNOTCH1, blocks YAP1 phosphorylation, and increases YAP1-TEAD transcriptional regulation on QKI [69][125] (Figure 12). The notch signaling pathway could thus a GPER targets in lung cancer. In lung cancer, heavy metals can activate the GPER and related signaling pathways. For example, cadmium chloride and sodium arsenite have been shown to enhance the proliferation of human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines by activating GPER/ERs/ERK/MAPK signaling pathways [70][126]. Bisphenol A (BPA), a ubiquitous pollutant with endocrine disrupting effects, may increase carcinogenesis susceptibility as treatment with BPA promotes the migration and invasion of human lung cancer cells, an effect linked to morphological changes and matrix MMP-2 and MMP-9 overexpression mediated by GPER [71][127] (Figure 12). Furthermore, numerous estrogenic-synthetic chemicals activate GPER, including herbicides, plasticizers and pesticides [72][73][128,129]. According to a genotoxic study, BPA caused enhanced DNA damage in the Hep-2 cell line and oxidative damage in the MRC-5 cell line [74][130]. Co-exposure to BPA and doxorubicin (DOX) in both cell lines MRC-5 and Hep-2 demonstrated that BPA acts as a DOX antagonist and interacts with MRC-5 cells, a GPER-expressing cell line, which appears to be cell-type dependent, resulting in a non-monotonic response curve [74][130].

When estrogen binds to both ER and GPER, a signal is generated, which leads to increased cell proliferation [75][131] (Figure 12). The activity and expression levels of enzymes involved in estrogen production are upregulated in some cases. For instance, there was an increase in the mRNA level of estrogen metabolic enzymes (17β-HSD type 1 and aromatase) in the lungs of COPD patients compared to controls, implying that estrogen exposure has a role in the etiology of COPD [76][132] and possibly lung cancer [77][133]. Since the GPER has been associated with development of NSCLC, a selective GPER inhibitor, for example, the G15 has been linked to inhibition of this type of cancer development by reversing E2-induced cell proliferation [78][134]. Thus, GPER dynamics could be a factor in lung carcinogenesis.

Figure 12. GPER signaling pathways in lung and endometrial cancer. Several ligands such as Estrogen, heavy metals and AMF bind to the GPER leading to the activation and subsequent cellular proliferation, inversion, growth and survival via the GPER/cAMP/PKA/CREB, GPER/RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and GPER/ERs/ERK/MAPK pathways. Estrogen may also bind to both ER and GPER and generated a signal which leads to increased cell proliferation. GPER-1 interacts with AMF and promotes PI3K signaling resulting in cancer cell growth. TET1 played a key role in upregulating GPER expression and also activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thus making insulin as a stimulator of EC cell proliferation through TET1-mediated GPER upregulation. ATP = Adenosine Triphosphate, cAMP = cyclic Adenosine monophosphate, YAP = Yes-Associated Protein, PKA = protein Kinase A, PKC = Protein Kinase C, Akt = Protein Kinase B, AMF = Autocrine Motility Factor, AMFR = Autocrine Motility Factor Receptor, ERK = extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase, CREB = cAMP response element binding protein, BPA = Bisphenol A, MAPK = Mitogen-activated protein kinase, PI3K = phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase, TET1 = tet methyl cytosine dioxygenase 1, RAF = Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma, RAS = rat sarcoma, MEK = mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase, ERK = Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase, EGFR = Epidermal growth factor receptor, JNK = c-JUN N-terminal kinase, ERα = Estrogen receptor α.

4. GPER in Gastric Cancer

Gastric cancer is the sixth most frequent cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related death [79][135]. This type of cancer develops from malignant cells in the stomach lining, and is divided into two topographic subtypes: cardia gastric cancers, which develop closest to the esophagus, and non-cardia cancers, which develop farther away [80][136]. When compared to normal tissues and cells, the GPER mRNA and protein levels were lower in gastric cancer tissue and in cells examined, demonstrating that, in gastric cancer, decreased GPER expression predicts for poor prognosis [81][9]. GPER expression stimulates G-1-induced anticancer effects by increasing cleaved poly ADP-ribose polymerase, caspases activity, and ER-stress signaling-induced expression of PERK, ATF-4, GRP-78, and CHOP [82][137]. Accordingly, the stresses generated in the ER by G-1 promote gastric cancer cell death. Knockdown of GPER-1 inhibited GC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, as well as downregulated mesenchymal markers (vimentin and N-cadherin), upregulated the epithelial marker E-cadherin, and suppressed expression of the transcription factors [83][138]. The GPER polymorphisms of rs3808350 and rs3808351 were strongly connected with cancer propensity, notably for the Asian population, and, in malignant tissues, cancer severity and advancement were correlated with rs3808351 and GPER expression in malignant tissues [84][139]. By implication, these results show that GPER is a player in genetic polymorphisms associated with gastric cancer.

5. GPER in Colon/Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is a term used to describe two types of cancer that affect the large intestine: colon and rectal cancer [85][140]. Colon and colorectal cancers are similar in that they both originate in the large intestine. However, although colon cancers originate in the colon, colorectal cancers originate in the rectum [85][140]. The implication of this is that since the rectum has proximity to other organs, metastasis is more common with rectal cancer than colon cancer [86][141]. Men are more prone to rectal cancer than women [86][141]. Additionally, due to factors requiring further research, the rectal mucosa is far more prone to carcinogenesis and malignancies than the colon mucosa [85][140]. The risk for developing colorectal cancers is higher in Europe and America when compared to Africa and Asia, with a projected increase of 60 to 70% in colorectal cancer- associated deaths by 2035 [86][141].

The challenges associated with the management of colorectal cancers have necessitated research into the pathophysiology of these diseases [87][142]. Estrogen has function in gastrointestinal motility including colon motility [88][143]. Estrogen receptors are expressed all through the gastrointestinal tract, pointing to estrogen-mediated signaling in gastrointestinal and colon function [89][144]. Thus, experiments have examined the role of GPER in colorectal cancers [90][91][145,146]. A study involving adult female mice showed GPER expression in colonic myenteric neurons, and reduced colonic transit and increased nitric oxide production on the administration of a GPER blocker (G15) and increased nitric oxide production on administration of GPER agonist (G1), thereby pointing to GPER mediated effects on colonic motility [92][147]. Immunohistochemistry results from in vivo studies using mice and human colons, showed GPER expression with inhibition of muscle contractility observed when G1 and estradiol were administered in vivo [90][145]. In colon tissues of colorectal cancer patients, GPER expression was observed to be significantly downregulated compared to matched normal tissues [93][148]. Further lower GPER expression in the tumors of patients was associated with poor survival rates when compared to those expressing higher GPER levels in tumor tissues [93][148].

Considering these observations, further studies are needed to examine the potential of GPER agonists as a therapeutic target. Such studies should take into consideration the age of patients, ancestry, and stage of cancer. The results from such studies would provide insight into the potential of GPER as a therapeutic target for colorectal cancers

6. GPER Signaling in Renal, Liver, and Pancreatic Cancer

Recently, immunohistochemical staining techniques employing an anti-human GPER monoclonal antibody (20H15L21) revealed, among 31 tumor entities, GPER protein expression in human renal, hepatocellular, and pancreatic tumors [94][149]. However, the authors reported that only pancreatic and renal cell carcinomas have showed moderate to strong and potentially clinically relevant GPER expression patterns [94][149], which projects that receptor as a potential diagnostic option or therapeutic target in these cancers. Moreover, emerging in silico data are beginning to uncover the molecular mechanism of GPER-ligand interactions. A phenylalanine cluster at the GPER active site is essential for GPER recognition by its agonists and antagonists and this molecular scaffold is proposed to be the binding site of some synthetic tetrahydroquinoline derivatives that inhibit the proliferation of human renal, liver, and pancreatic cancer cell lines in vitro [95][150]. The finding thus provides insight into the potential role of GPER in the pharmacological treatment of these cancers.

6.1. Renal Cancer

Although it accounts for just about 2% of the global cancer burden, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the deadliest and the third most common urinary malignancy [96][97][151,152]. RCC cell lines exhibit high GPER protein expression levels, and GPER activation in these cells is involved in RCC metastasis [97][98][152,153]. For instance, by activating GPER, aldosterone promotes RCC metastasis in murine RCC cell lines in a dose-dependent manner [98][153]. In a recent study, G1-mediated pharmacological activation of GPER promoted the migration and invasion of RCC cells, which mechanistically involves the GPER-mediated upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) via PI3K/Akt signaling [97][152]. ThWe researchers ccould thus infer from these observations that GPER promotes RCC metastasis by modulating the expression and function of extracellular matrix proteins involved in the EMT of RCC cells via the PI3K/Akt signaling axis and perhaps by yet-to-be-discovered signaling pathways.

6.2. Liver Cancer

Regarding liver cancer, a study reported that GPER could serve as a prognostic biomarker in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients because its protein expression is downregulated in the cancerous tissues of patients compared to normal controls, and this downregulation is associated with poor overall survival [99][154]. The authors also reported that G1 inhibited tumor growth of HCC xenografts by activating GPER/EGFR/ERK signaling [99][154], indicating that the pharmacological activation of GPER could be a viable therapeutic strategy for HCC patients. Tamoxifen-mediated GPER activation downregulated RhoA levels, which in turn reduced the phosphorylation of MLC-2 (an actomyosin regulatory protein that controls ECM contractility in HSCs) and also suppressed YAP activation; actinomycin and YAP activation are necessary for the development of fibrosis in HCC tumors [100][157]. The authors also reaffirmed that tamoxifen-mediated modulation of GPER/RhoA/myosin signaling impeded the adaptability of HCC cells to hypoxia-induced necrosis by downregulating HIF-1α gene expression [100][157]. The studies thus provide insight into the possible involvement of GPER in the mechanical remodeling of the tumor microenvironment and prevention of hepatic fibrosis for HCC patients. Accordingly, in a previous mechanistic study that dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)-mediated GPER activation promoted tumorigenesis in human HCC cell lines by upregulating miR-21 transcription via a GPER/Src/EGFR/MAPK signaling cascade [101][158]. Based on the research outcomes, the signaling cascade increases miR-21 transcription by promoting the recruitment of the androgen receptor, c-Fos, and c-Jun to its promoter [101][158]. It is noteworthy that miR-21 is oncogenic and overexpressed in HCC cells, and, according to the authors, the RNA in human HCC tumors is actively involved in the downregulation of tumor suppressor genes such as PDCD4 [101][158]. This study, therefore, suggests that epigenetic mechanisms are involved in the GPER-mediated DHEA-induced HCC tumorigenesis.

6.3. Pancreatic Cancer

Evidence suggests that GPER proteins are expressed in tissue samples of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients, and the survival probability in these patients increases significantly with an increase in GPER expression [102][103][159,160]. Furthermore, G-1-mediated GPER activation inhibited the EMT and, therefore, the metastasis of PDAC cell lines by suppressing the contractility and mechanotransduction capacity of the cells via a GPER/RhoA/myosin-2-mediated deactivation of YAP [102][159]. Similarly, tamoxifen-induced GPER signaling increases vascularization and inhibits fibrosis and the hypoxic response in PDAC cell lines via the GPER/RhoA/myosin/HIF-1A axis [104][105][161,162]. These observations support the role of GPER in the RhoA-mediated regulation of the mechanical properties of the tumor microenvironment of HCC cells as reported [100][157] and thus present RhoA as a promising target in the GPER-mediated pharmacological treatment of these cancers. Further, G-1-mediated GPER activation inhibited the proliferation of human and murine PDAC cell lines by enhancing their susceptibility to immune destruction via downregulating the protein expression of c-Myc and its target, PD-L1, which are required for the proliferation, invasion, and escape of PDAC cells from immune surveillance [103][160].

7. GPER in Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial cancer is a uterine cancer that starts in the lining of the uterus, and represents the most common gynecological cancer in the developed world [106][163]. This type of cancer starts in the layer of cells that make up the uterine lining (endometrium). According to research, GPER interacts with the autocrine motility factor (AMF) and promotes PI3K signaling, promoting endometrial cancer (EC) cell growth [107][164]. GPER also regulates diacylglycerol kinase (DGK) activity, which is necessary for 17-estradiol (E2)-induced proliferation, motility, and anchorage-independent development of the Hec-1A endometrial cancer cell line [108][165]. Expression of endometrial estrogen receptors (ERa, ERb, and GPER) is essential for regular menstrual cycles and eventual pregnancy [109][166], and therefore altered expression of these receptors may lead to endometriosis, endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial carcinoma which may affect many women of reproductive age [109][166]. Endometrial cancer has about 6-fold lower GPER mRNA expression than normal endometrium, and G-1 treatment slowed the growth of the GPER-positive cell lines but had no effect on a GPER-negative cell line [110][167]. Thus, the expression of GPER in the cell could help anticancer agents to slowing down cancer cell growth and exhibit greater efficacy. The expression of Egr-1 in breast and endometrial cancer cells is stimulated by E2 and hydroxytamoxifen (OHT) and mediated via GPER/EGFR/ERK signaling and in model cell lines (breast and endometrial cancer cells). Egr-1 is necessary for the proliferative effects generated by E2, OHT, and G-1 [44][99]. GPER expression was higher in the endometrial tissues of EEC participants with insulin resistance, and insulin, through epigenetic regulation, increased TET1 and GPER expression [111][168]. Low GPER mRNA causes loss of GPER protein from the primary tumor to metastatic lesions, which ultimately translates to disease progression [112][169]. In endometrial cancer, miR195 inhibits cell migration and invasion by targeting GPER and inhibiting the epithelial-mesenchymal transition; both GPER expression and the AKT/PI3K signaling pathway were found to be involved [113][170].

A novel tamoxifen analogue referred to as STX activates GPER, resulting in stimulation of GPER and possibly elevating estrogen levels, as well as activating the PI3K and MAPK pathways, causing endometrial cancers proliferation [114][171]. GPER mediates estrogen-stimulated activation of ERK and PI3K via matrix metalloproteinase activation and subsequent EGFR transactivation (Figure 12), and thus ER-targeted medicinal drugs act as GPER agonists in this regard, and pharmacological inhibition of GPER activity may inhibit estrogen-mediated endometrial tumor growth [22][77]. Tamoxifen has been associated with endometrial cancer proliferative effects and lymph node metastases in users, and this proliferative impact is driven by the GPER/EFGR/ERK/cyclin D1 pathway, which might be blocked by GPER silencing [115][172]. The impact of insulin-induced TET-1 expression and subsequent expression of GPER has been studied. Accordingly, insulin increased TET1 expression, and TET1 was involved in upregulating GPER expression and activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thus allowing insulin to stimulate EC cell proliferation through TET1-mediated GPER upregulation [116][173]. Despite having a diverse expression of estrogen biosynthesis and metabolic genes, various EC models have been discovered to produce estrogens only via the sulfatase route. These cells, however, expressed all of the major genes involved in the production of hydroxy estrogens and estrogen quinones, as well as their conjugation [117][174]. The involvement of TET1 in the GPER system, specifically in EC, points to the fact that GPER epigenomics could be among the underlying molecular mechanisms of EC proliferation.

8. GPER in Melanoma Skin Cancer

Melanoma, the most dangerous skin cancer which occurs due to the abnormal growth of melanocytes that are responsible for skin color [118][175]. As per the American Cancer Society’s estimation for melanoma in the United States, about 99,780 new melanomas will be diagnosed, and about 7650 people are expected to die of melanoma in 2022 [119][176]. In addition, racial disparities also exist for melanoma as it is 20 times more common in whites than in African Americans. There are several risk factors linked to melanoma, including sun (UV) exposure, family history, gender (being male), age, skin color, and genetic mutations (predominantly CDKN2A) [120][121][177,178]. In search of new treatment methods, it was observed that specific gender (female), multiple records of pregnancies, and early age of first pregnancy are correlated with a reduction in melanoma [122][123][179,180]. Therefore, it was thought that sex hormone signaling must be involved. Between 1996 and 1998, four distinct laboratories discovered GPR30, now recognized as GPER, which is structurally different from the classical estrogen receptor (ER) [124][125][181,182]. Later, it was discovered that elevated levels of estrogen during the pregnancy phase act upon melanocytes to boost pigment production and melanocyte differentiation [126][183]. These estrogenic effects are mediated by GPER [126][183]. In addition, scientists made a hypothesis that studying the relevant hormones, receptors, and downstream signaling proteins activated in melanocytes by pregnancy-related sex hormones could lead to a breakthrough [127][184]. Accordingly, they discovered that GPER fosters melanoma differentiation, inhibits tumor cell proliferation, and promotes the susceptibility of cancer cells to immune-mediated elimination [127][184]. Moreover, Natale et al. cloned the oncogene BRAF in human melanoma tissue and grafted the product into mice. Later, the mice were divided into breeding and non-breeding groups. Expectedly, melanoma was not observed in the breeding group as per the hypothesis [127][184]. In this experiment, they portrayed how depletion of c-myc protein stops the progression of melanoma. However, there is currently no FDA-approved drug acting as a c-myc inhibitor on the global market.

High levels of Myc protein inhibit the genesis of HLA and also increase the production of PDL1, which impedes immune recognition of cancer cells; therefore, T-cells cannot recognize the melanoma cancer cells [127][128][184,185]. Scientists also came up with GPER agonists for example, G-1, which showed anti-tumor activity. In their quest for a therapeutic model, they tried GPER agonists and differentiation-based immunotherapy. This opened a new horizon to invent a specific GPER agonist possibly to be used with combination therapy to treat melanoma. Furthermore, they found that the mice with tumors in which the GPER was activated responded better to immunotherapy than those without the GPER treatment. It may be deduced from the experiment that estrogens enhance the immune response of female patients against melanoma [127][184]. However, further research should be conducted to discover specific GPER-activated drugs with immunotherapy combinations that can serve as better treatment options for melanoma patients. Additionally, scientists also studied the role of GPER in melanogenesis in the human melanoma cell line (A375) and the mouse melanoma cell line (B16) [129][186]. The authors reported that GPER increases melanogenesis in these cell lines by upregulating microphthalmia-related transcription factor-tyrosinase via activating the cAMP-protein kinase A (PKA) signaling. These findings, therefore, imply that GPER is a potential drug target for chloasma or melanoma [129][186]. In another study involving mice model [130][187], it was found that treatment with the GPER agonist G1 of mouse melanoma K1735- M2 cells decreased cell biomass and the number of viable cells without an increase in cell death. Altogether, these studies demonstrate that GPER as a potential target in melanoma therapy.

IHC staining techniques were used to measure the protein expression of GPER in melanoma tumors [131][188]. To validate the GPER effect on melanoma, a comparative study [132][189] was carried out with the other classical estrogen receptors (ER-α, β) in common nevi, dysplastic nevi, and melanomas. In this study, GPER expression was substantial in nuclei and cytoplasm of dysplastic nevi and margins compared to melanoma [132][189]. Most melanomas expressed ERβ and GPER, but the expression was different in margins and sebaceous glands in melanoma and non-melanoma lesions [132][189]. This points to these receptors as prospective biomarkers. Considering the wealth of evidence that directs the impact of GPER on melanoma cell lines and tumors, thwe researchers postulate that GPER could be a potential therapeutic target for melanoma patients.

9. GPER in Cervical Cancer

To date, cervical cancer (CC) has remained by far, a major malignancy affecting women worldwide with human papillomavirus (HPV) considered the major etiologic agent [133][190]. This is due to the higher prevalence of the virus in most of the women diagnosed with CC. The virus encodes oncogenic proteins (E6 and E7) that are involved in signaling and participates in various cascades of events that ultimately lead to the development of cancer [134][191]. Infection alone with the HPV is not sufficient to establish CC in the patients, as the interplay of other factors is required to fully dictate the final malignant transformation [135][192].

Epigenetic modifications and signaling have been considered relevant phenomena in cancer progression [136][193]. For instance, the E6 and E7 oncoproteins from HPV are associated with the activation and induction of signaling pathways (notably Akt, Wnt/B catenin, and Smad proteins among others) leading to the activation or repression of certain genes implicated in CC [135][192]. The hormone (estrogen), the function of which is mediated through the estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), and the G protein-coupled estrogen receptors (GPER/GPR30) have been associated with the development of CC [73][129]. Although high expressions of the ER receptors were associated with disease advancement, the activation of the GPER/GPR30, particularly in the tissue, is involved in cancer biology [73][129]. A study conducted employing qPCR, Western blots, and immunofluorescence techniques showed that, in HeLa and SiHa cells, E6 and E7 oncogenes increased the expressions of ERα, GPER/GPR30, and prolactin receptors (PRLR) and that the oncogenes modified the location of the receptors to the cytoplasm (in the case of PRLR) and nucleus (for the ERs and GPER/GPR30) [135][192] (Table 3). Hofsjo et al. compared the expression pattern of the sex steroid hormone receptors in CC survivors and non-infected women (control) [137][194]. Concerning GPER/GPR30, a non-significant difference in the expression of the receptor in both the epithelium and stroma of CC survivors and the control women was observed following immunohistochemistry scoring [137][194].

Similarly, GPER expression was detected in most tissues collected from CC patients, as well as in different subcellular tissue staining patterns [138][195]. In the study, there was a positive correlation between cytoplasmic GPER staining and CC tumor suppressor p16 and p53 (but not mutant), although, on the contrary, there was no association between the GPER and E6 and E7 oncogenes [138][195]. Hence, the study revealed that, in early-stage CC, GPER positivity could be an excellent predictor of overall and progression-free survival [138][195]. Moreover, there was a negative correlation between Lysine Specific Demethylase 1 (LSD1) and GPER/GPR30 was observed in 250 cervical cancers [139][196]. LSD1 demethylates lysine 4 of histone H3 serving as a transcriptional co-repressor. Hence the findings reported a disadvantaged 10 years of survival for CC patients with strong LSD1 expressions [139][196]. Further, mono-2- Ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP) was found to increases the proliferation of HeLa and SiHa cells and increased the phosphorylation and nuclear localization of Akt in the CC cells, an effect that was reversed in both cells following knockdown of GPER/GPR30 in both cells [140][197]. Overall, the studies revealed that GPER participated in the compound-induced activation of Akt. Hence, the compound could subsequently trigger the CC progression due to the activation of the GPER/Akt system [140][197]. These findings implicated GPER in CC epigenetics.

10. GPER in Thyroid Cancer

Thyroid cancer (TC) is another class of estrogen-related cancer that frequently occurs in women, and, similar to CC, estrogen binds the GPER with high affinity (in addition to ER-α), thereby mediating cascades of reactions leading to the activation of signaling pathways and related genes in TC [141][198]. For instance, in thyroid cancer cell lines, there is high expression of GPER, similar to MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines. This in turn leads to activation of ERK and AKT pathways, hence, causing increased nuclear translocation of NF-kB and subsequently leading to the activation of downstream genes, including cyclin A, cyclin D1, and interleukin 8 (IL-8) [141][198]. Bertoni et al. found low expression of GPER in papillary thyroid carcinoma which could be associated with BRAF mutation (PTC) [142][199]. However, the study further revealed a positive correlation of the GPER mRNA expression level with thyroid differentiation genes [142][199]. Although a recent review suggested that disease progression could be mediated by the GPER, there were inconsistent findings on the role of the protein in the TC [143][200]. Overall, the limited studies on the role of GPER in TC suggest the need for a thorough investigation on the role of GPER in the progression of TC.

11. GPER in Ovarian Carcinoma

According to the American Cancer Society, about 12,810 women in the United States will die from ovarian cancer in 2022. Ovarian tumors are classified into three main subtypes: ovarian epithelial carcinomas, germ cell tumors, and stromal cell tumors (sex cord) [144][201]. These malignancies are differentiated by cell/site of origin, histological appearance, risk factors, and clinical characteristics [145][202]. Unfortunately, most patients (4 out of 5) with ovarian cancer are diagnosed with advanced disease, and epithelial carcinoma accounts for 85–90% of the cases [146][4]. Estrogen, the primary sex hormone in females [147][203], and is involved in breast, endometrial, and ovarian physiology. Mainly, estrogens are synthesized in the ovaries and adrenal glands [148][204] and regulate the growth and differentiation in the normal ovaries. Moreover, estrogens are involved in the progression of ovarian cancer. There are three physiological subtypes of estrogens: estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), and estriol (E3), with E2 being the major and most active subtype [149][205]. These three forms of estrogen bind to the GPER [150][206], which is involved in rapid estrogen signaling. GPER expression varies with age, gender, and tissue. Estrogens binding to GPER induce ovarian cancer cell proliferation through activation of multiple downstream signals such as ERK (extracellular-signal-regulated kinase), PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase), and EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) [151][207]. Additionally, GPER overexpression enhances Akt phosphorylation via EGFR. Both GPER and EGFR overexpression is associated with poor outcome for ovarian cancer [152][208]. The upstream regulation of GPER is induced explicitly by LH/FSH along with FSHR-GPER dimerization which stimulates FSH-Stimulated Ovarian Follicle viability via Gβγ dimers [153][209]. Furthermore, GPER regulates the migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells (SKOV3 and OVCAR5), and targeting of GPER could provide a new therapeutic strategy for ovarian cancer [154][155][210,211].

On the other hand, Tanja Ignatov et al., and Wang, Cheng, et al. proved that GPER acts as a tumor suppressor in ovarian cancer, and the expression of GPER was lower in ovarian cancer tissue compared to benign as well as early-stage cancers [156][157][212,213]. This finding aligns with the observations made by other researchers that support GPER as a tumor suppressor in ovarian carcinoma [158][214]. Fraungruber, Patricia, et al. addressed the connections between estrogen and Wnt signaling in ovarian cancer. They showed that the combined expression of GPER and the Wnt pathway modulator Dickkopf 2 (Dkk2) signaling pathway is associated with improved overall survival (OS) [159][215]. Moreover, Zhu, Cai-Xia, et al. group [160][216] showed that GPER expression varied in different histological subtypes of ovarian cancer. The same group explained that cytoplasmic localization of GPER is not associated with the outcome, but nuclear GPER predicts 5-year progression-free survival and poor survival for ovarian cancer patients. In contrast, Kolkova, Zuzana, et al. consider that, for patients with ovarian cancer, neither GPER mRNA nor protein predicts survival, and they do not correlate with histological or clinical parameters in patients with ovarian cancer [161][217]. Therefore, the role of GPER in ovarian carcinoma is still controversial and not clear.

The impact of GPER on cancer cell growth or suppression depends on the cancer type and tissue target. The previous findings demonstrate the complex roles of GPER in ovarian carcinoma that need additional research. In addition, since numerous areas lack knowledge about GPER and its function, further investigation is required. For example, it was reported in one study covering the epigenetic regulation of GPER in ovarian tumors that GPER activation epigenetically regulates the trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) and ERK1/2, which leads to cell proliferation and migration inhibition in ovarian cancer cells [162][218].

12. GPER in Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common malignancy affecting men. Although the incidence and mortality rates vary worldwide, PCa remains the second-leading cause of cancer death in the US [163][219]. According to the American Cancer Society, approximately 268,490 new cases of PCa will be observed and 34,500 people will die, in 2022. The most common histological subtype is prostate adenocarcinoma, which can rapidly progress into hormone-refractory prostate cancer (HRPC). The biological heterogeneity of prostate cancer reveals the disease complexity in clinical and research settings [164][220]. However, several studies imply that alterations of different pathways involving growth factor receptors are involved in prostate cancer aggressiveness [165][221]. Growth factor receptors (mainly EGFR) and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) mediate a complex signaling network that activates relevant biological effects in cancer cells [166][222].

Moreover, GPCRs, mainly GPER, regulate multiple biological responses [167][223], including cancer cell proliferation and migration. Both androgens and estrogens mediate prostate cancer development and differentiation, and their combined effect induces disease aggressiveness [168][224]. Of note, estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) are found sequentially in stromal cells and epithelial lumen cells of the prostate gland [169][225], and activation of these receptors leads to premalignant and metastatic lesions [170][226]. Wide-ranging findings on the roles of ERα and ERβ in prostate cancer suggested that ERβ was predominantly protective, and ERα was tumor-promoting [171][227]. Additionally, GPER is an estrogen mediator detected in male reproductive cells (such as testicular cells and spermatozoa). Still, its expression in prostatic tissue has not been reported yet. The Rago, V., et al. group reported that GPER has strong immunoreactivity in the cytoplasm of basal epithelial cells as well as in Gleason pattern 2 or Gleason pattern3, but no immunostaining was evident in luminal secretory epithelial cells. Even though there was a historical use of estrogens in the pathogenesis of PCa, their biological effect is not well known, nor is their role in carcinogenesis [172][228]. Ramírez-de-Arellano, Adrián, et al. reported the mechanism of GPER associated with ER and GPER in PCa [172][228]. Nevertheless, more studies need to be accomplished to explore in depth the role of GPER in prostate cancer prognosis as well as the mechanisms used to carry their therapeutic effects of neoplastic in prostate transformation and the possibility of targeting GPER in advanced diseases in addition to epigenetic regulation of GPER in PCa.