Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorders with maturation and differentiation defects, exhibiting morphological dysplasia in one or more hematopoietic cell lineages, and are characterized by increased risk for progression into acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Among their multifactorial pathogenesis, age-related epigenetic instability and the error-rate DNA methylation maintenance have been recognized as critical factors for both, the initial steps of their pathogenesis and disease progression. DNA-modifying enzymes, commonly mutated in MDS, play a crucial role in this epigenetic drift.

- myelodysplastic syndromes

- acute myeloid leukemia

- aberrant DNA methylation

- pathogenesis

- epigenetics

- small non-coding RNAs

1. Introduction

2. The Course of Aberrant DNA Methylation Patterns in MDS

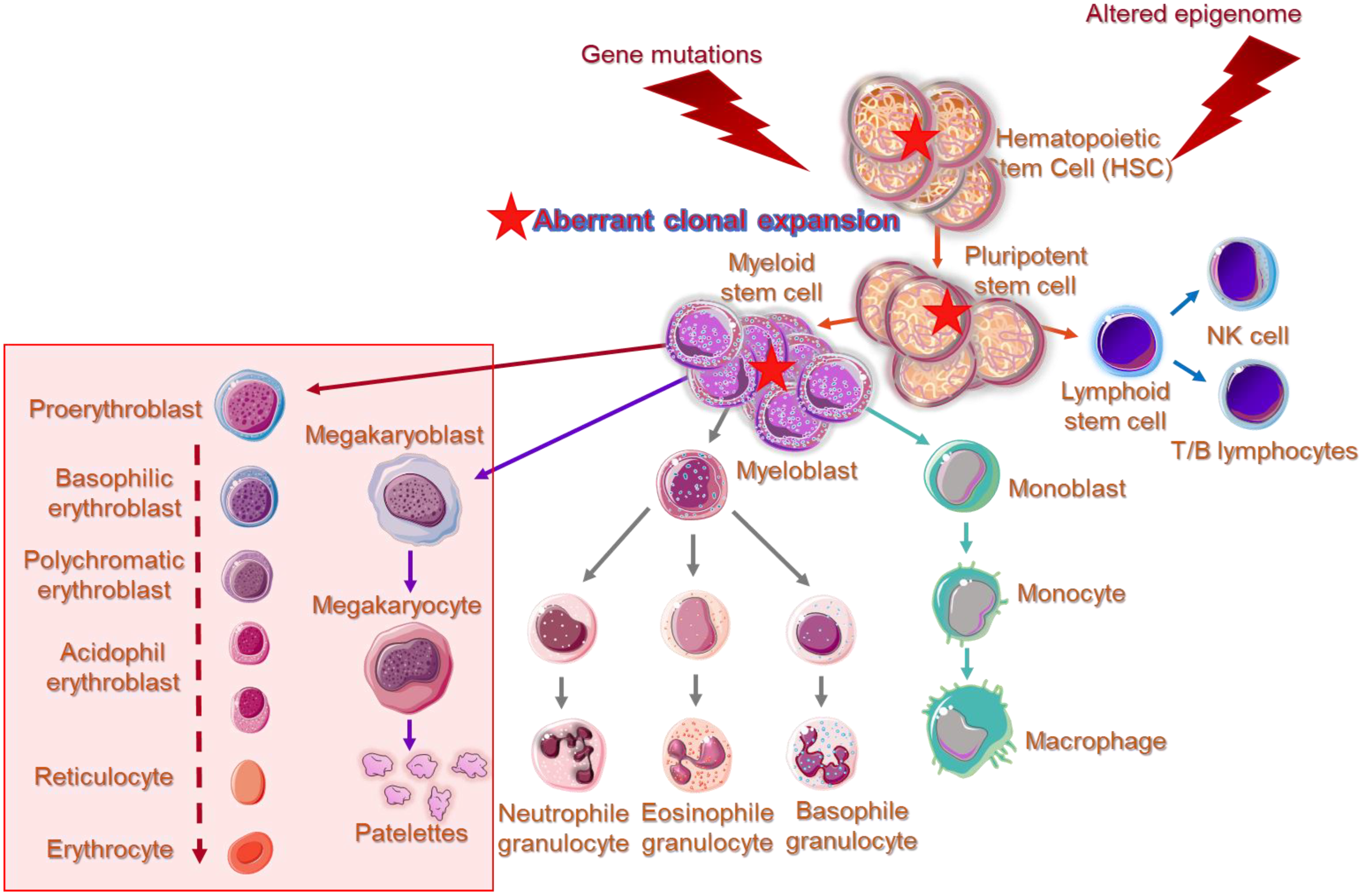

DNA methylation is an essential epigenetic mechanism, playing very important role in the regulation of gametogenesis and zygote development in mammals (orchestrating the rounds of erasing and re-methylating of maternal and paternal derived chromosomes), imprinting and tissue-specific gene’s expression, and preservation of DNA hypermethylation as a suppressing mechanism for the locomotion of repetitive DNA elements [1424][1525][1626]. Herein, enzymes responsible for epigenetic gene reprogramming are considered as delicate sensors of environmental signaling leading to cell responses and differential gene expression profiles. In particular, the epigenetic mark created by a methyl group covalent transfer, derived from the S-adenosyl methionine (SAM), to the 5′C position of a cytosine (C) either in scattered CpG dinucleotides across DNA sequences or in CpG islands, is catalyzed by DNMTs. By a rough classification DNMT1 is considered as the maintenance DNMT, which targets the hemi-methylated double stranded (ds)DNA to preserve the DNA methylation patterns post DNA replication and DNMT3A/DNMT3B as the de novo methylation enzymes, reacting with hemi-methylated and unmethylated dsDNA [1727][1828]. Contrary to DNMT1, responsible for the inherited DNA methylation, DNMT3A and DNMT3B are normally expressed and act during embryonic development or gametogenesis, independently from DNA replication. These enzymes share identical enzymatic centers at carboxyl-ends and different sequence patterns across N-ends that serve for communication with other molecules and for recognition and binding to DNA [1929]. DNA recognition by DNMT3A and DNMT3B, apart from the N-terminal PWWP domain (‘Pro-Trp-Trp-Pro’ core amino acid sequence) by which bind to DNA, depends also on flanking sequences neighboring CpG targets. DNMT3B shows a significant preference for CpG methylation in a TACG (G/A) context [2030], while other research groups have predicted that DNMT3A and DNMT3B preferentially methylate some representative sequences, more frequently found in naturally over-methylated genes [2131][2232] or that DNMTs in general, favor recruitment at DNA repair sites [2333]. Furthermore, it has been reported that methylation of the Caspase-8 (CASP8) gene promoter in glioma cells is governed by both DNMT1 and DNMT3A, indicating a potential collaboration and concerted action of DNMTs [2434]. Specific recruitment assisted by transcription factors or chromatin remodeling complexes is another context supporting DNMTs’ symmetrical function on DNA methylation [2535]. However, there are still some interesting questions, such as the broader DNA architecture and/or epigenetic landscape that allows DNMTs to bind to CpG target sites in preferable or cognate sites or whether the flanking sequence preferences adapt to specific biological targets of DNMTs. Within this frame of action, crosstalk of DNMTs with non-coding RNA species as potential guides to specific sites for methylation across genome, remains an issue deserving further investigation. DNMT3A and DNMT3B are frequently associated with divergent de novo DNA methylation patterns and gene repression in many pathologies. A common observation is that Myelodysplastic Syndromes are developed under an aberrant epigenetic background [610]. Cell cycle regulators, apoptotic genes, and DNA repair genes are irregularly silenced through epigenetic modifications, promoting clonal dominance and expansion of abnormal hematopoietic stem cell, favoring gradual disease progression or in association with various other somatic mutations, the transformation to AML [2636]. Figure 1 illustrates phenotypic and functional cell alterations in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) compartment of bone marrow, associated with HR-MDS that guide disease progression to AML. In MDS-derived secondary AML, mutations among the DNMTs and the TET family of genes contributing to demethylating genome pathways are frequently identified, suggesting that aberrant epigenetic programming plays a crucial role in MDS progression [610].

3. Non-Coding RNA Species Cooperate with DNA Modifying Enzymes

In addition to DNMTs, other epigenetic components, such as microRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) exhibit altered expression profiles in MDS patients, following treatment with HMAs and during disease progression, whereas long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been shown to direct the activity of epigenetic mechanisms and chromatin remodeling complexes in many genetic loci, influencing gene expression. DNA methylation spreading restrictions depending on RNA inhibition is a cooperative epigenetic phenomenon, and potentially represents a global way of inter-regulation between mechanisms, which are still considered distinct. So far there are few, but well-documented paradigms of interrelations between small non-coding RNA and proteins related to DNA or formation of DNA-ncRNA hybrids with regulatory functions. Current knowledge and future perspectives in nc-RNA interaction with DNA-modifying enzymes in MDS are well described in the recent work.

Under the enlightenment of these important but still restricted data, it is anticipated that nc-RNAs could potentially mediate the accurate targeting of CpG sites across the genome, offering guidance to DNMTs via sequence complementarity (between DNA and RNA) or alternatively, they could play the role of scaffolds, that recruit other DNA-modifying enzymes. Non-coding RNAs with secondary loops, such as the inter-nuclear transcribed pre-miRNA clusters and lncRNAs govern the structural principles for DNA–RNA–protein interactions. The above-mentioned speculations remain to be highlighted and elucidated in the near future.

References

- Malcovati, L.; Hellstrom-Lindberg, E.; Bowen, D.; Ades, L.; Cermak, J.; Del Canizo, C.; Della Porta, M.G.; Fenaux, P.; Gattermann, N.; Germing, U.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary myelodysplastic syndromes in adults: Recommendations from the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 2013, 122, 2943–2964.

- Greenberg, P.; Cox, C.; LeBeau, M.M.; Fenaux, P.; Morel, P.; Sanz, G.; Sanz, M.; Vallespi, T.; Hamblin, T.; Oscier, D.; et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 1997, 89, 2079–2088.

- Greenberg, P.L.; Tuechler, H.; Schanz, J.; Sanz, G.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Sole, F.; Bennett, J.M.; Bowen, D.; Fenaux, P.; Dreyfus, F.; et al. Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2012, 120, 2454–2465.

- Papaemmanuil, E.; Gerstung, M.; Malcovati, L.; Tauro, S.; Gundem, G.; van Loo, P.; Yoon, C.J.; Ellis, P.; Wedge, D.C.; Pellagatti, A.; et al. Clinical and biological implications of driver mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2013, 122, 3616–3627. Figueroa, M.E.; Skrabanek, L.; Li, Y.; Jiemjit, A.; Fandy, T.E.; Paietta, E.; Fernandez, H.; Tallman, M.S.; Greally, J.M.; Carraway, H.; et al. MDS and secondary AML display unique patterns and abundance of aberrant DNA methylation. Blood 2009, 114, 3448–3458.

- Haferlach, T.; Nagata, Y.; Grossmann, V.; Okuno, Y.; Bacher, U.; Nagae, G.; Schnittger, S.; Sanada, M.; Kon, A.; Alpermann, T.; et al. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 2014, 28, 241–247. Maegawa, S.; Gough, S.M.; Watanabe-Okochi, N.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Castoro, R.J.; Estecio, M.R.; Jelinek, J.; Liang, S.; Kitamura, T.; et al. Age-related epigenetic drift in the pathogenesis of MDS and AML. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 580–591.

- Heuser, M.; Yun, H.; Thol, F. Epigenetics in myelodysplastic syndromes. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 51, 170–179. Jiang, Y.; Dunbar, A.; Gondek, L.P.; Mohan, S.; Rataul, M.; O’Keefe, C.; Sekeres, M.; Saunthararajah, Y.; Maciejewski, J.P. Aberrant DNA methylation is a dominant mechanism in MDS progression to AML. Blood 2009, 113, 1315–1325.

- Madzo, J.; Vasanthakumar, A.; Godley, L.A. Perturbations of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine patterning in hematologic malignancies. Semin. Hematol. 2013, 50, 61–69. Zhao, X.; Yang, F.; Li, S.; Liu, M.; Ying, S.; Jia, X.; Wang, X. CpG island methylator phenotype of myelodysplastic syndrome identified through genome-wide profiling of DNA methylation and gene expression. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 165, 649–658.

- Reitman, Z.J.; Jin, G.; Karoly, E.D.; Spasojevic, I.; Yang, J.; Kinzler, K.W.; He, Y.; Bigner, D.D.; Vogelstein, B.; Yan, H. Profiling the effects of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations on the cellular metabolome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3270–3275. Papaemmanuil, E.; Gerstung, M.; Malcovati, L.; Tauro, S.; Gundem, G.; van Loo, P.; Yoon, C.J.; Ellis, P.; Wedge, D.C.; Pellagatti, A.; et al. Clinical and biological implications of driver mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2013, 122, 3616–3627.

- Ghoshal, K.; Datta, J.; Majumder, S.; Bai, S.; Kutay, H.; Motiwala, T.; Jacob, S.T. 5-Aza-deoxycytidine induces selective degradation of DNA methyltransferase 1 by a proteasomal pathway that requires the KEN box, bromo-adjacent homology domain, and nuclear localization signal. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 4727–4741. Haferlach, T.; Nagata, Y.; Grossmann, V.; Okuno, Y.; Bacher, U.; Nagae, G.; Schnittger, S.; Sanada, M.; Kon, A.; Alpermann, T.; et al. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 2014, 28, 241–247.

- Hollenbach, P.W.; Nguyen, A.N.; Brady, H.; Williams, M.; Ning, Y.; Richard, N.; Krushel, L.; Aukerman, S.L.; Heise, C.; MacBeth, K.J. A comparison of azacitidine and decitabine activities in acute myeloid leukemia cell lines. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9001. Heuser, M.; Yun, H.; Thol, F. Epigenetics in myelodysplastic syndromes. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 51, 170–179.

- Dombret, H.; Seymour, J.F.; Butrym, A.; Wierzbowska, A.; Selleslag, D.; Jang, J.H.; Kumar, R.; Cavenagh, J.; Schuh, A.C.; Candoni, A.; et al. International phase 3 study of azacitidine vs conventional care regimens in older patients with newly diagnosed AML with >30% blasts. Blood 2015, 126, 291–299. Madzo, J.; Vasanthakumar, A.; Godley, L.A. Perturbations of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine patterning in hematologic malignancies. Semin. Hematol. 2013, 50, 61–69.

- Fenaux, P.; Mufti, G.J.; Hellstrom-Lindberg, E.; Santini, V.; Finelli, C.; Giagounidis, A.; Schoch, R.; Gattermann, N.; Sanz, G.; List, A.; et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: A randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 223–232. Reitman, Z.J.; Jin, G.; Karoly, E.D.; Spasojevic, I.; Yang, J.; Kinzler, K.W.; He, Y.; Bigner, D.D.; Vogelstein, B.; Yan, H. Profiling the effects of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations on the cellular metabolome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3270–3275.

- Zeidan, A.M.; Stahl, M.; DeVeaux, M.; Giri, S.; Huntington, S.; Podoltsev, N.; Wang, R.; Ma, X.; Davidoff, A.J.; Gore, S.D. Counseling patients with higher-risk MDS regarding survival with azacitidine therapy: Are we using realistic estimates? Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 55. Bond, D.R.; Lee, H.J.; Enjeti, A.K. Unravelling the Epigenome of Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Response to Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 3128.

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, T. DNA Methylation Reprogramming during Mammalian Development. Genes 2019, 10, 257. Zimta, A.A.; Tomuleasa, C.; Sahnoune, I.; Calin, G.A.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. Long Non-coding RNAs in Myeloid Malignancies. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1048.

- Dodge, J.E.; Okano, M.; Dick, F.; Tsujimoto, N.; Chen, T.; Wang, S.; Ueda, Y.; Dyson, N.; Li, E. Inactivation of Dnmt3b in mouse embryonic fibroblasts results in DNA hypomethylation, chromosomal instability, and spontaneous immortalization. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 17986–17991. Huang, H.H.; Chen, F.Y.; Chou, W.C.; Hou, H.A.; Ko, B.S.; Lin, C.T.; Tang, J.L.; Li, C.C.; Yao, M.; Tsay, W.; et al. Long non-coding RNA HOXB-AS3 promotes myeloid cell proliferation and its higher expression is an adverse prognostic marker in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 617.

- Gowher, H.; Jeltsch, A. Mammalian DNA methyltransferases: New discoveries and open questions. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 1191–1202. Kuang, X.; Chi, J.; Wang, L. Deregulated microRNA expression and its pathogenetic implications for myelodysplastic syndromes. Hematology 2016, 21, 593–602.

- Jurkowska, R.Z.; Jurkowski, T.P.; Jeltsch, A. Structure and function of mammalian DNA methyltransferases. ChemBioChem Eur. J. Chem. Biol. 2011, 12, 206–222. Kirimura, S.; Kurata, M.; Nakagawa, Y.; Onishi, I.; Abe-Suzuki, S.; Abe, S.; Yamamoto, K.; Kitagawa, M. Role of microRNA-29b in myelodysplastic syndromes during transformation to overt leukaemia. Pathology 2016, 48, 233–241.

- Klose, R.J.; Bird, A.P. Genomic DNA methylation: The mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006, 31, 89–97. Lyu, C.; Liu, K.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Xu, R. Integrated analysis on mRNA microarray and microRNA microarray to screen immune-related biomarkers and pathways in myelodysplastic syndrome. Hematology 2021, 26, 417–431.

- Margot, J.B.; Cardoso, M.C.; Leonhardt, H. Mammalian DNA methyltransferases show different subnuclear distributions. J. Cell. Biochem. 2001, 83, 373–379. Ghoshal, K.; Datta, J.; Majumder, S.; Bai, S.; Kutay, H.; Motiwala, T.; Jacob, S.T. 5-Aza-deoxycytidine induces selective degradation of DNA methyltransferase 1 by a proteasomal pathway that requires the KEN box, bromo-adjacent homology domain, and nuclear localization signal. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 4727–4741.

- Dukatz, M.; Adam, S.; Biswal, M.; Song, J.; Bashtrykov, P.; Jeltsch, A. Complex DNA sequence readout mechanisms of the DNMT3B DNA methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 11495–11509. Hollenbach, P.W.; Nguyen, A.N.; Brady, H.; Williams, M.; Ning, Y.; Richard, N.; Krushel, L.; Aukerman, S.L.; Heise, C.; MacBeth, K.J. A comparison of azacitidine and decitabine activities in acute myeloid leukemia cell lines. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9001.

- Lin, I.G.; Han, L.; Taghva, A.; O’Brien, L.E.; Hsieh, C.L. Murine de novo methyltransferase Dnmt3a demonstrates strand asymmetry and site preference in the methylation of DNA in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 704–723. Dombret, H.; Seymour, J.F.; Butrym, A.; Wierzbowska, A.; Selleslag, D.; Jang, J.H.; Kumar, R.; Cavenagh, J.; Schuh, A.C.; Candoni, A.; et al. International phase 3 study of azacitidine vs conventional care regimens in older patients with newly diagnosed AML with >30% blasts. Blood 2015, 126, 291–299.

- Takahashi, M.; Kamei, Y.; Ehara, T.; Yuan, X.; Suganami, T.; Takai-Igarashi, T.; Hatada, I.; Ogawa, Y. Analysis of DNA methylation change induced by Dnmt3b in mouse hepatocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 434, 873–878. Fenaux, P.; Mufti, G.J.; Hellstrom-Lindberg, E.; Santini, V.; Finelli, C.; Giagounidis, A.; Schoch, R.; Gattermann, N.; Sanz, G.; List, A.; et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: A randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 223–232.

- Mortusewicz, O.; Schermelleh, L.; Walter, J.; Cardoso, M.C.; Leonhardt, H. Recruitment of DNA methyltransferase I to DNA repair sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8905–8909. Zeidan, A.M.; Stahl, M.; DeVeaux, M.; Giri, S.; Huntington, S.; Podoltsev, N.; Wang, R.; Ma, X.; Davidoff, A.J.; Gore, S.D. Counseling patients with higher-risk MDS regarding survival with azacitidine therapy: Are we using realistic estimates? Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 55.

- Hervouet, E.; Vallette, F.M.; Cartron, P.F. Impact of the DNA methyltransferases expression on the methylation status of apoptosis-associated genes in glioblastoma multiforme. Cell Death Dis. 2010, 1, e8. Zeng, Y.; Chen, T. DNA Methylation Reprogramming during Mammalian Development. Genes 2019, 10, 257.

- Hervouet, E.; Peixoto, P.; Delage-Mourroux, R.; Boyer-Guittaut, M.; Cartron, P.F. Specific or not specific recruitment of DNMTs for DNA methylation, an epigenetic dilemma. Clin. Epigenetics 2018, 10, 17. Dodge, J.E.; Okano, M.; Dick, F.; Tsujimoto, N.; Chen, T.; Wang, S.; Ueda, Y.; Dyson, N.; Li, E. Inactivation of Dnmt3b in mouse embryonic fibroblasts results in DNA hypomethylation, chromosomal instability, and spontaneous immortalization. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 17986–17991.

- Khan, H.; Vale, C.; Bhagat, T.; Verma, A. Role of DNA methylation in the pathogenesis and treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Semin. Hematol. 2013, 50, 16–37. Gowher, H.; Jeltsch, A. Mammalian DNA methyltransferases: New discoveries and open questions. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 1191–1202.

- Lopez, V.; Fernandez, A.F.; Fraga, M.F. The role of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in development, aging and age-related diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 37, 28–38. Jurkowska, R.Z.; Jurkowski, T.P.; Jeltsch, A. Structure and function of mammalian DNA methyltransferases. ChemBioChem Eur. J. Chem. Biol. 2011, 12, 206–222.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C. Formation and biological consequences of 5-Formylcytosine in genomic DNA. DNA Repair 2019, 81, 102649. Klose, R.J.; Bird, A.P. Genomic DNA methylation: The mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006, 31, 89–97.

- Szulik, M.W.; Pallan, P.S.; Nocek, B.; Voehler, M.; Banerjee, S.; Brooks, S.; Joachimiak, A.; Egli, M.; Eichman, B.F.; Stone, M.P. Differential stabilities and sequence-dependent base pair opening dynamics of Watson-Crick base pairs with 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-formylcytosine, or 5-carboxylcytosine. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 1294–1305. Margot, J.B.; Cardoso, M.C.; Leonhardt, H. Mammalian DNA methyltransferases show different subnuclear distributions. J. Cell. Biochem. 2001, 83, 373–379.

- Nimer, S.D. Myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2008, 111, 4841–4851. Dukatz, M.; Adam, S.; Biswal, M.; Song, J.; Bashtrykov, P.; Jeltsch, A. Complex DNA sequence readout mechanisms of the DNMT3B DNA methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 11495–11509.

- Van Rompay, A.R.; Norda, A.; Linden, K.; Johansson, M.; Karlsson, A. Phosphorylation of uridine and cytidine nucleoside analogs by two human uridine-cytidine kinases. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 59, 1181–1186. Lin, I.G.; Han, L.; Taghva, A.; O’Brien, L.E.; Hsieh, C.L. Murine de novo methyltransferase Dnmt3a demonstrates strand asymmetry and site preference in the methylation of DNA in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 704–723.

- Creusot, F.; Acs, G.; Christman, J.K. Inhibition of DNA methyltransferase and induction of Friend erythroleukemia cell differentiation by 5-azacytidine and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 2041–2048. Takahashi, M.; Kamei, Y.; Ehara, T.; Yuan, X.; Suganami, T.; Takai-Igarashi, T.; Hatada, I.; Ogawa, Y. Analysis of DNA methylation change induced by Dnmt3b in mouse hepatocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 434, 873–878.

- Ghoshal, K.; Datta, J.; Majumder, S.; Bai, S.; Dong, X.; Parthun, M.; Jacob, S.T. Inhibitors of histone deacetylase and DNA methyltransferase synergistically activate the methylated metallothionein I promoter by activating the transcription factor MTF-1 and forming an open chromatin structure. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 8302–8319. Mortusewicz, O.; Schermelleh, L.; Walter, J.; Cardoso, M.C.; Leonhardt, H. Recruitment of DNA methyltransferase I to DNA repair sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8905–8909.

- Datta, J.; Ghoshal, K.; Motiwala, T.; Jacob, S.T. Novel Insights into the Molecular Mechanism of Action of DNA Hypomethylating Agents: Role of Protein Kinase C delta in Decitabine-Induced Degradation of DNA Methyltransferase 1. Genes Cancer 2012, 3, 71–81. Hervouet, E.; Vallette, F.M.; Cartron, P.F. Impact of the DNA methyltransferases expression on the methylation status of apoptosis-associated genes in glioblastoma multiforme. Cell Death Dis. 2010, 1, e8.

- Easwaran, H.P.; Schermelleh, L.; Leonhardt, H.; Cardoso, M.C. Replication-independent chromatin loading of Dnmt1 during G2 and M phases. EMBO Rep. 2004, 5, 1181–1186. Hervouet, E.; Peixoto, P.; Delage-Mourroux, R.; Boyer-Guittaut, M.; Cartron, P.F. Specific or not specific recruitment of DNMTs for DNA methylation, an epigenetic dilemma. Clin. Epigenetics 2018, 10, 17.

- Diesch, J.; Zwick, A.; Garz, A.K.; Palau, A.; Buschbeck, M.; Gotze, K.S. A clinical-molecular update on azanucleoside-based therapy for the treatment of hematologic cancers. Clin. Epigenetics 2016, 8, 71. Khan, H.; Vale, C.; Bhagat, T.; Verma, A. Role of DNA methylation in the pathogenesis and treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Semin. Hematol. 2013, 50, 16–37.

- Stomper, J.; Rotondo, J.C.; Greve, G.; Lubbert, M. Hypomethylating agents (HMA) for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes: Mechanisms of resistance and novel HMA-based therapies. Leukemia 2021, 35, 1873–1889. Lopez, V.; Fernandez, A.F.; Fraga, M.F. The role of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in development, aging and age-related diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 37, 28–38.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C. Formation and biological consequences of 5-Formylcytosine in genomic DNA. DNA Repair 2019, 81, 102649.

- Szulik, M.W.; Pallan, P.S.; Nocek, B.; Voehler, M.; Banerjee, S.; Brooks, S.; Joachimiak, A.; Egli, M.; Eichman, B.F.; Stone, M.P. Differential stabilities and sequence-dependent base pair opening dynamics of Watson-Crick base pairs with 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-formylcytosine, or 5-carboxylcytosine. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 1294–1305.

- Nimer, S.D. Myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2008, 111, 4841–4851.

- Van Rompay, A.R.; Norda, A.; Linden, K.; Johansson, M.; Karlsson, A. Phosphorylation of uridine and cytidine nucleoside analogs by two human uridine-cytidine kinases. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 59, 1181–1186.

- Creusot, F.; Acs, G.; Christman, J.K. Inhibition of DNA methyltransferase and induction of Friend erythroleukemia cell differentiation by 5-azacytidine and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 2041–2048.

- Ghoshal, K.; Datta, J.; Majumder, S.; Bai, S.; Dong, X.; Parthun, M.; Jacob, S.T. Inhibitors of histone deacetylase and DNA methyltransferase synergistically activate the methylated metallothionein I promoter by activating the transcription factor MTF-1 and forming an open chromatin structure. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 8302–8319.

- Datta, J.; Ghoshal, K.; Motiwala, T.; Jacob, S.T. Novel Insights into the Molecular Mechanism of Action of DNA Hypomethylating Agents: Role of Protein Kinase C delta in Decitabine-Induced Degradation of DNA Methyltransferase 1. Genes Cancer 2012, 3, 71–81.

- Easwaran, H.P.; Schermelleh, L.; Leonhardt, H.; Cardoso, M.C. Replication-independent chromatin loading of Dnmt1 during G2 and M phases. EMBO Rep. 2004, 5, 1181–1186.

- Diesch, J.; Zwick, A.; Garz, A.K.; Palau, A.; Buschbeck, M.; Gotze, K.S. A clinical-molecular update on azanucleoside-based therapy for the treatment of hematologic cancers. Clin. Epigenetics 2016, 8, 71.

- Stomper, J.; Rotondo, J.C.; Greve, G.; Lubbert, M. Hypomethylating agents (HMA) for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes: Mechanisms of resistance and novel HMA-based therapies. Leukemia 2021, 35, 1873–1889.