Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorders with maturation and differentiation defects, exhibiting morphological dysplasia in one or more hematopoietic cell lineages, and are characterized by increased risk for progression into acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Among their multifactorial pathogenesis, age-related epigenetic instability and the error-rate DNA methylation maintenance have been recognized as critical factors for both, the initial steps of their pathogenesis and disease progression. DNA-modifying enzymes, commonly mutated in MDS, play a crucial role in this epigenetic drift.

- myelodysplastic syndromes

- acute myeloid leukemia

- aberrant DNA methylation

- pathogenesis

- epigenetics

- small non-coding RNAs

1. Introduction

- Introduction

Among the complex and multifactorial pathophysiology of MDS, apart from various somatic mutations, occurring at genetic loci with essential role in the growth, development and differentiation of hematopoietic cells, hypermethylation of several genetic loci plays a dominant role in all phases of the disease, from the generation of a clonal cell population until disease evolution to AML [4,5,6,7].

In MDS commonly mutated genes, which are implicated in epigenetics, include DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) DNMT1 and mainly DNMT3A, the family of methyl-cytosine dioxygenases TET1-3 and the isocitrate dehydrogenases IDH1-2, contributing to the generation of aberrant methylation/demethylation genomic imprints [8,9,10]. DNMTs catalyze the reaction of cytosine methylation on DNA CpG dinucleotides, while the family of TET enzymes converts 5-methylcytocine (5mC) to 5-hydroxy-methylcytocine (5hmC) and other downstream oxidative products, which leads to DNA demethylation in daughter cells due to the inability of DNMT1 to recognize the modification from 5mC to 5hmC [11]. Isocitrate dehydrogenases catalyze the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate to 2-oxoglutarate. Mutated IDH1 catalyzes the synthesis of 2-hydroxyglutarate, which inhibits alpha-ketoglutarate dependent enzymes such as the TETs and the histone demethylases, which in turn, indirectly lead to elevation of 5mC levels within the genome, and to a hypermethylated phenotype [12]. Mutation of these enzyme families have been associated with harmful pathogenetic consequences, often acquired with advancing age and they are well known to be involved in disorders, such as MDS and various cancers of epithelial origin.

Hypomethylating agents (HMAs), mainly azacytidine (AZA) and decitabine (DAC), used in clinical practice, are primarily considered inhibitors of DNMTs, mostly of DNMT1 [19]. AZA and DAC are both, chemical nucleoside analogs of cytidine with identical ring structure, thus acting also as antimetabolites inside the rapidly proliferating immature clonal cells, besides their inhibitory activity on DNMTs. These agents, after incorporation into DNA and/or RNA of highly proliferating cells, mainly induce DNMT1 depletion and global DNA hypomethylation. However, their function is not equivalent, and distinctly different effects have been reported for their specific mode of action, with AZA exhibiting a greater effect on the reduction of cell viability and total protein synthesis and on restoration of onco-suppressing gene expression [20].

Efforts to understand in depth step by step the pathogenetic mechanisms of MDS, although challenging, have not resulted in much therapeutic progress in recent years. For almost the last two decades HMAs remain the mainstay of treatment for non-transplant eligible patients, with higher-risk MDS (HR-MDS) and AML, despite the fact that only 30–50% of them may achieve a substantial and durable response [21,22]. Although HMAs are in use for long time, an association of demethylating effect on specific DNA hypermethylated loci with particular clinical outcomes and patterns of response, remains yet to be shown, while their broader mode of action on gene expression regulation is still unclear. According to current clinical experience, median overall survival with HMA monotherapy is about two years for HR-MDS patients [23] and less than a year for those with AML [21]. This observation implies that additional mechanisms, beyond specific genomic hypo/demethylation events are developed, ascribing to clonal cells a biologically more aggressive/leukemic phenotype. Thus, several classes of novel agents, modifying different targets and promising to act synergistically with HMAs, are emerging, in an effort to overcome the generation of resistance. RNA-based therapeutic agents are still in pre-clinical investigation and only a few of them have entered the clinical stage to evaluate their value in practice.

- The Course of Aberrant DNA Methylation Patterns in MDS

DNA methylation is an essential epigenetic mechanism, playing a very important role in the regulation of gametogenesis and zygote development in mammals (orchestrating the rounds of erasing and re-methylating of maternal and paternal derived chromosomes), imprinting tissue-specific gene expression, and the preservation of DNA hypermethylation, as a suppressing mechanism for the locomotion of repetitive DNA elements [24,25,26]. Herein, enzymes responsible for epigenetic gene reprogramming are considered as delicate sensors of environmental signaling, leading to altered cell responses and to differential gene expression profiles. In particular, the epigenetic mark, created by a methyl group covalent transfer, derived from the S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to the 5′C position of a cytosine (C), either in scattered CpG dinucleotides across DNA sequences or in CpG islands, is catalyzed by DNMTs. By a rough classification DNMT1 is considered as the maintenance DNMT, which targets the hemi-methylated double stranded (ds)DNA, to preserve the DNA methylation patterns post DNA replication, and DNMT3A/DNMT3B as the de novo methylation enzymes, reacting with hemi-methylated and unmethylated dsDNA [27,28]. Contrary to DNMT1, which is responsible for the inherited DNA methylation, DNMT3A and DNMT3B are normally expressed and act during embryonic development or gametogenesis, independently from DNA replication. These enzymes share identical enzymatic centers at their carboxyl-ends and different sequence patterns across their N-ends, that serve for communication with other molecules and for recognition and binding to DNA [29]. DNA recognition by DNMT3A and DNMT3B, apart from the N-terminal PWWP domain (‘Pro-Trp-Trp-Pro’ core amino acid sequence) by which they bind to DNA, depends also on flanking sequences neighboring CpG targets. DNMT3B shows a significant preference for CpG methylation in a TACG (G/A) context [30], while other research groups have predicted that DNMT3A and DNMT3B preferentially methylate some representative sequences, more frequently found in naturally over-methylated genes [31,32] or that DNMTs in general, favor recruitment at DNA repair sites [33]. Furthermore, it has been reported that methylation of the Caspase-8 (CASP8) gene promoter in glioma cells is governed by both, DNMT1 and DNMT3A, indicating a potential collaboration and concerted action of DNMTs [34]. Specific recruitment assisted by transcription factors or chromatin remodeling complexes is another context supporting DNMTs’ symmetrical function on DNA methylation [35]. However, there are still some interesting questions, such as the broader DNA architecture and/or epigenetic landscape that allows DNMTs to bind to CpG target sites in preferable or cognate sites or whether the flanking sequence preferences adapt to specific biological targets of DNMTs. Moreover, critical questions, such as whether the DNMTs target the same groups of CpG islands in different cell types or how DNMTs selectively act on specific CpGs, which become hypermethylated, while others remain rather unaffected, also need a deeper insight. Within this frame of action, crosstalk of DNMTs with non-coding RNA species, as potential guides to specific sites for methylation across genome, remains an issue deserving further investigation.

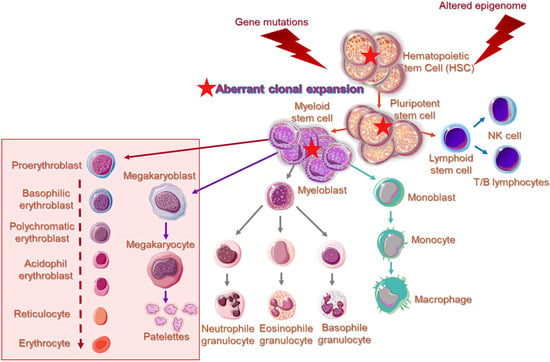

DNMT3A and DNMT3B are frequently associated with divergent de novo DNA methylation patterns and gene repression in many pathologies. A common observation is that MDS are developed under an aberrant epigenetic background [10], on an abnormal bone marrow immune microenvironment [*]. Cell cycle regulators, apoptotic genes, and DNA repair genes are irregularly silenced through epigenetic modifications, and in association with the coexistent immune dysregulation promote clonal dominance and expansion of abnormal hematopoietic stem cells, favoring gradual disease progression or in association with various other somatic mutations, the transformation to AML [36]. Figure 1 illustrates phenotypic and functional cell alterations in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) compartment of bone marrow, associated with HR-MDS that guide disease progression to AML. In MDS-derived secondary AML, mutations among the DNMTs and the TET family of genes contributing to demethylating genome pathways are frequently identified, suggesting that aberrant epigenetic programming plays a crucial role in MDS progression [10].

2. The Course of Aberrant DNA Methylation Patterns in MDS

DNA methylation is an essential epigenetic mechanism, playing very important role in the regulation of gametogenesis and zygote development in mammals (orchestrating the rounds of erasing and re-methylating of maternal and paternal derived chromosomes), imprinting and tissue-specific gene’s expression, and preservation of DNA hypermethylation as a suppressing mechanism for the locomotion of repetitive DNA elements [14][15][16]. Herein, enzymes responsible for epigenetic gene reprogramming are considered as delicate sensors of environmental signaling leading to cell responses and differential gene expression profiles. In particular, the epigenetic mark created by a methyl group covalent transfer, derived from the S-adenosyl methionine (SAM), to the 5′C position of a cytosine (C) either in scattered CpG dinucleotides across DNA sequences or in CpG islands, is catalyzed by DNMTs. By a rough classification DNMT1 is considered as the maintenance DNMT, which targets the hemi-methylated double stranded (ds)DNA to preserve the DNA methylation patterns post DNA replication and DNMT3A/DNMT3B as the de novo methylation enzymes, reacting with hemi-methylated and unmethylated dsDNA [17][18]. Contrary to DNMT1, responsible for the inherited DNA methylation, DNMT3A and DNMT3B are normally expressed and act during embryonic development or gametogenesis, independently from DNA replication. These enzymes share identical enzymatic centers at carboxyl-ends and different sequence patterns across N-ends that serve for communication with other molecules and for recognition and binding to DNA [19]. DNA recognition by DNMT3A and DNMT3B, apart from the N-terminal PWWP domain (‘Pro-Trp-Trp-Pro’ core amino acid sequence) by which bind to DNA, depends also on flanking sequences neighboring CpG targets. DNMT3B shows a significant preference for CpG methylation in a TACG (G/A) context [20], while other research groups have predicted that DNMT3A and DNMT3B preferentially methylate some representative sequences, more frequently found in naturally over-methylated genes [21][22] or that DNMTs in general, favor recruitment at DNA repair sites [23]. Furthermore, it has been reported that methylation of the Caspase-8 (CASP8) gene promoter in glioma cells is governed by both DNMT1 and DNMT3A, indicating a potential collaboration and concerted action of DNMTs [24]. Specific recruitment assisted by transcription factors or chromatin remodeling complexes is another context supporting DNMTs’ symmetrical function on DNA methylation [25]. However, there are still some interesting questions, such as the broader DNA architecture and/or epigenetic landscape that allows DNMTs to bind to CpG target sites in preferable or cognate sites or whether the flanking sequence preferences adapt to specific biological targets of DNMTs. Within this frame of action, crosstalk of DNMTs with non-coding RNA species as potential guides to specific sites for methylation across genome, remains an issue deserving further investigation. DNMT3A and DNMT3B are frequently associated with divergent de novo DNA methylation patterns and gene repression in many pathologies. A common observation is that Myelodysplastic Syndromes are developed under an aberrant epigenetic background [6]. Cell cycle regulators, apoptotic genes, and DNA repair genes are irregularly silenced through epigenetic modifications, promoting clonal dominance and expansion of abnormal hematopoietic stem cell, favoring gradual disease progression or in association with various other somatic mutations, the transformation to AML [26]. Figure 1 illustrates phenotypic and functional cell alterations in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) compartment of bone marrow, associated with HR-MDS that guide disease progression to AML. In MDS-derived secondary AML, mutations among the DNMTs and the TET family of genes contributing to demethylating genome pathways are frequently identified, suggesting that aberrant epigenetic programming plays a crucial role in MDS progression [6].

. Overview of cell aberrations in epigenome of higher-risk MDS patients within the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) compartment. Impaired gene expression implicated in maturation and differentiation of pluripotent stem cells give rise to myeloid lineage-committed cells, showing further phenotypical as well as functional changes. Higher-risk MDS patients present significantly expanded granulocytic-monocytic progenitor cells and HSC compartments, while the megakaryocytic–erythroid progenitor cell population is severely reduced. Cellular and molecular changes are in line with the observed peripheral blood cytopenias and emergence of aberrant immature cells in the bone marrow and peripheral blood of MDS patients. Aberrant cells, characterized by the generation of multiple copies per cell, are indicated by a solid red star. Obstructed pathways of myelopoiesis and erythropoiesis are indicated within a transparent rectangle.

Cytosine methylation in CpG dinucleotides is a critical epigenetic modification, although it can be reversible. DNA demethylation occurs via a stepwise oxidation of 5-methylcytosine that is catalyzed by the Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) or methyl-cytosine dioxygenases enzymes. The first oxidation product in this process, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), has been shown to act as a unique epigenetic mark, which, in contrast to 5mC, is linked to transcriptional activation. 5hmC has been implicated in the activation of lineage-specific enhancers and in substantial cell processes [37]. The oxidation pathway generates also several other intermediates (i.e. formylcytosine and carboxylcytosine), that have their own distinct biological functions [38]. The 5hmC has a functional role in promoting gene expression during active demethylation, where conversion of 5mC to 5hmC by the TETs prevent the recognition of DNA sequences by repressive (Methyl-Binding) MBD-domain complexes and DNMT proteins that would typically be recruited to rich 5mC areas [39]. The issue of cytosine epigenetic modifications across DNA CpG rich sequences apparently provides another layer of regulation, beyond the canonical genetic codes.

Hypomethylating agents (HMAs) are mainly administered as treatment to HR-MDS patients with increased percentage of bone marrow blasts, carrying a high risk for AML progression [40]. Among the most widely administered MDS treatment approaches, AZA and DAC, are considered inhibitors of DNMT1, which is almost completely depleted after HMA exposure, whereas DNMT3A, which is significantly less sensitive and DNMT3B, seems completely resistant to HMAs [19]. DAC is tri-phosphorylated and is incorporated into newly synthesized DNA as a substitute for cytosine (antimetabolite), which pairs with guanine assisted by DNA-polymerase. In contrast, AZA is converted to ribonucleoside triphosphate and is incorporated into RNA, leading to inhibition of protein synthesis [41]. Investigation has shown that DNMT1 activity decreases faster than incorporation of HMAs into DNA [19,42,43] and DNMT1 depletion occurs even in the absence of DNA replication and cell division [44,45]. The proposed DNMT1 depletion mechanism supporting these data, is that HMAs induce DNMT1 degradation in the nucleus via its rapid hyperphosphorylation by the protein kinase C delta (PKCd), followed by ubiquitination and finally leading to proteasomal degradation [19]. Although shared epigenetic mechanisms of action have been affiliated to both, AZA and DAC, such as the DNMT1 depletion and global DNA hypomethylation, their function is not equivalent. Distinctive effects have been reported on many cellular responses, such as cell viability and gene expression [20]. In proliferating cells, inactivation of DMNT1 after starting treatment with HMAs, results in a persistent hemi-methylated DNA status delivered to next generations of daughter cells. However, HMAs’ reversible activity towards the abnormal epigenetic stem cell profiles and reactivation of aberrantly silenced genes is moderate to low [46]. Moreover, the effect of HMA treatment on lymphocyte function and its impact on the achievement of a favorable or unfavorable response has not yet been adequately investigated. Response to HMA treatment is not always easily predictable, despite the proposal of various markers of response, since the required molecular genetic testing is not usually applied in routine clinical practice, and most MDS patients, who receive HMA therapy develop resistance to treatment over time and present disease progression to AML [47].

3. Non-Coding RNA Species Cooperate with DNA Modifying Enzymes

- Non-Coding RNA Species Cooperate with DNA Modifying Enzymes

In addition to DNMTs, other epigenetic components, such as microRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) exhibit altered expression profiles in MDS patients, following treatment with HMAs and during disease progression, whereas long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been shown to direct the activity of epigenetic mechanisms and chromatin remodeling complexes in many genetic loci, influencing gene expression. DNA methylation spreading restrictions depending on RNA inhibition is a cooperative epigenetic phenomenon, and potentially represents a global way of inter-regulation between mechanisms, which are still considered distinct. So far there are few, but well-documented paradigms of interrelations between small non-coding RNA and proteins related to DNA or formation of DNA-ncRNA hybrids with regulatory functions. Current knowledge and future perspectives in nc-RNA interaction with DNA-modifying enzymes in MDS are well described in theour recent work.

Under the enlightenment of these important but still restricted data, it is anticipated that nc-RNAs could potentially mediate the accurate targeting of CpG sites across the genome, offering guidance to DNMTs via sequence complementarity (between DNA and RNA) or alternatively, they could play the role of scaffolds, that recruit other DNA-modifying enzymes. Non-coding RNAs with secondary loops, such as the inter-nuclear transcribed pre-miRNA clusters and lncRNAs govern the structural principles for DNA–RNA–protein interactions. The above-mentioned speculations remain to be highlighted and elucidated in the near future.

[*] Kouroukli O, Symeonidis A, Foukas P, Maragkou MK, Kourea EP: Bone Marrow Immune Microenviron-ment in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Cancers 2022;14(22):5656. doi: 10.3390/cancers14225656. PMID: 36428749.