Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Joseph Arsebe Arsene Mbarga Mbarga Manga.

Experience-based knowledge has shown that bacteria can communicate with each other through a cell-density-dependent mechanism called quorum sensing (QS). QS controls specific bacterial phenotypes, such as sporulation, virulence and pathogenesis, the production of degrading enzymes, bioluminescence, swarming motility, and biofilm formation. The expression of these phenotypes in food spoiling and pathogenic bacteria, which may occur in food, can have dramatic consequences on food production, the economy, and health.

- quorum sensing (QS)

- quorum quenching (QQ)

- QS inhibitors

- probiotics

1. Introduction

A few decades after the discovery of bacteria, the idea that bacteria were individualized organisms, and therefore did not communicate with each other, was accepted and established. However, after early research by Kenneth H. Nealson et al. [1] on the luminescence of the Gram-negative bacterium Vibrio fischeri (newly named Aliivibrio fischeri) [2], it became clear that bacteria communicate with each other [1]. Indeed, this research shows that bioluminescence in A. fischeri is induced and closely linked to bacterial density [1]. Later, it was found that this luminescence in A. fischeri is caused by the LuxI/LuxR transcriptional activator and autoinducer system mediating the cell-density-dependent control of Lux gene expression [3]. This communicational regulation, which has since taken the name of quorum sensing, is generally defined as a mechanism of microbial communication owing to a genetic regulation that involves the exchange and sensing of low-molecular-weight signaling compounds called autoinducers (AIs) [4,5][4][5]. Over the last few years, there have been a significant number of studies on the role of QS systems in the formation of various cellular patterns and their behavioral response [6,7][6][7]. Thus, to date, several other bacteria have demonstrated their ability to communicate through QS, and some inter-species communications have even been brought to light [8]. QS can have serious consequences, as it is involved in many important biological processes that can have a detrimental impact on the economy and health, such as sporulation, virulence and pathogenesis, and biofilm formation [9,10][9][10]. The consequences on human health are not discussed here, but economically speaking, phenomena such as biofilm formation can cause enormous losses in the agriculture and food industry [11,12][11][12]. It is well known that biofilms are largely responsible for the contamination of processed products within the food industry [12]. These microbial consortia embedded in self-produced exopolymer matrices [13] adhere to food processing, packaging, and equipment surfaces, and can negatively affect food safety [8,14][8][14]. Recent studies have demonstrated that QS molecules play a major role in the biofilm formation of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [8]. Although this correlation was not found when studying in vitro biofilms of strains isolated from a raw vegetable processing line, other foodborne bacterial pathogens, such as Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus cereus, can attach to various surfaces within the food industry and develop biofilms, leading to concerning hygienic disorders and a severe public health risk [14].

Studies conducted in recent years have suggested that QS inhibition could be an attractive alternative strategy for current bacterial control practices employed in industrial settings [8,14,15][8][14][15]. Unlike conventional antibacterials and sanitizers, instead of killing bacteria, a strategy using QS inhibitors consists of blocking intercellular communication and significantly limiting the expression of phenotypes, such as the formation of biofilms, while reducing the likelihood of resistance development [15,16][15][16]. Several products with important biological functions (e.g., phytochemicals, nanoparticles, halogenated natural furanones, and synthesized derivatives) have already demonstrated their ability to delay the microbial deterioration of foods and defeat important bacterial strains involved in spoilage [8,17][8][17]. However, although several studies have shown that certain strains of probiotics can interfere with the QS system [18[18][19][20],19,20], reports or evidence of their use as QS inhibitors (QSIs) in food preservation are scarce.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO), probiotics are living microorganisms that provide health benefits to their hosts in appropriate doses [21]. Probiotics have applications in a variety of fields, including food processing, animal breeding, and human health [21]. The fact that probiotics are “generally recognized as safe” means that these food additives and their by-products can be used in different processes, including food preservation and the maintenance of industrial food surfaces, since their addition will not have side effects on food safety [22].

2. Quorum Quenching and QS Inhibitors from Probiotics

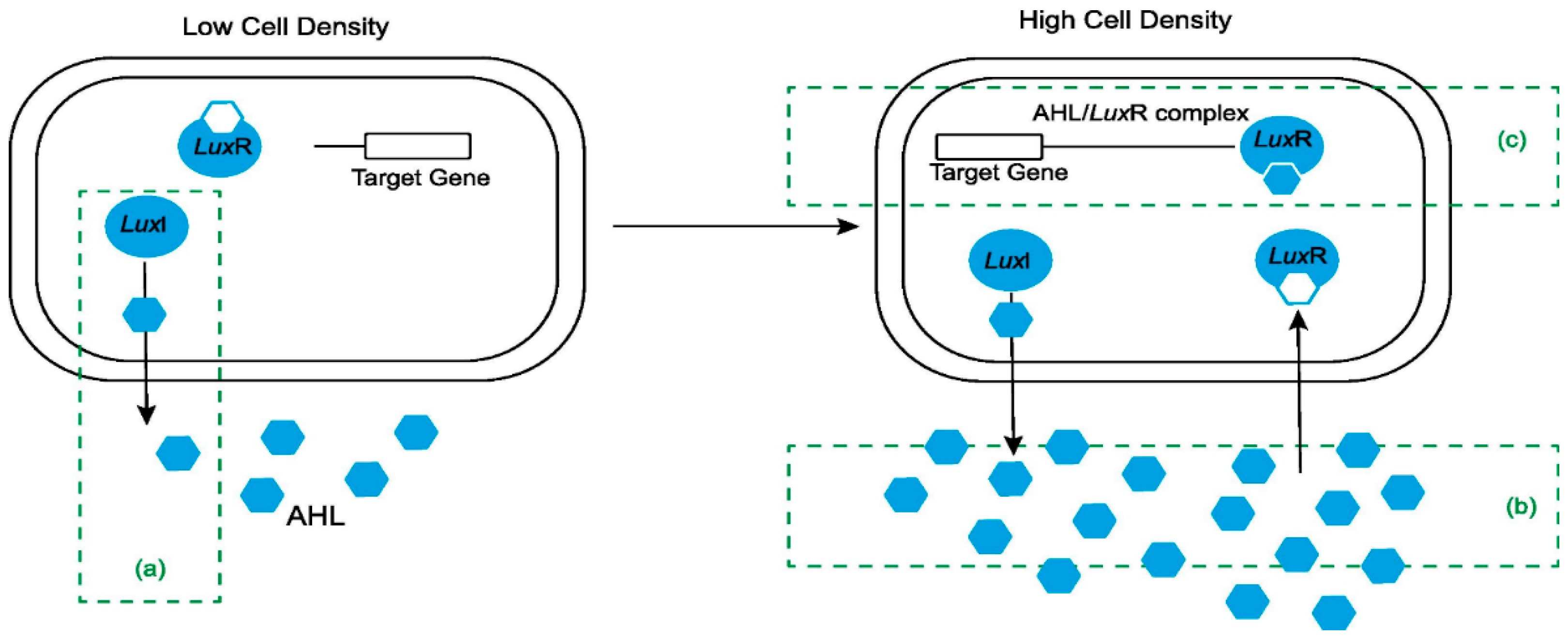

QS inhibition is due to quorum quenching (QQ) enzymes or, more generally, to other chemicals known as QS inhibitors (QSIs). Whether due to enzymes or other chemicals, the disruption of the QS system commonly takes the name of QQ [22]. QQ has been suggested as a strategy for disrupting a pathogen’s ability to sense its cell density and to modulate the production of virulence factors [22]. Some data suggest that QQ is increasingly recognized as a new strategy used to control specific bacterial phenotypes, such as sporulation, virulence and pathogenesis, bioluminescence, swarming motility, and biofilm formation [15]. As shown in Figure 1 (taken from the review by [8] with the permission of Elsevier), there are several putative ways to inhibit QS (Figure 1): (a) the interruption of AHL signal synthesis by blocking the LuxI-type synthase; (b) the degradation of AHL signal dissemination by enzymes (AHL-acylase and AHL-lactonase), which will impair AHL accumulation; and (c) interference with signal receptors or the blockage of the AHL/LuxR complex [8]. Natural and synthetic QSIs have been intensively studied and are produced by a wide range of organisms, such as plants, some animals from aqueous ecosystems, fungi, and bacteria [71][23].

Figure 1. Inhibition of quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria: (a) inhibition of AHL synthesis; (b) degradation of AI using enzymes; (c) interference with signal receptors (From [8] with permission from Elsevier; license number: 5433491396764).

Table 1. Some probiotic strains with QQ activity and the mechanism involved.

| Probiotics | Bacteria Inhibited | QSI Mechanism | References | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | |||||||||||

| Bacillus | B. subtilis | L. monocytogenes | E. coli | Gardnerella vaginalis | Inhibits AI-2 activity and biofilm formation | [86] | [38] | |||||

| B. cereus | RC1 | Lelliottia amnigena | seudomonas aeruginosa | MTCC2297 | Inhibits pyocyanin production in | P. aeruginosa | and modulates the pathogenicity in | L. amnigena | [87] | [39] | ||

| B. subtilis | R-18 | Serratia marcescens | The bacterial extract inhibits biofilm formation, protease, lipase, and hemolysin production | [88] | [40] | |||||||

| B. subtilis | BR4 | P. aeruginosa | Inhibits biofilm formation | [89] | [41] | |||||||

| B. pumilus | P. aeruginosa PAO1 | (las, rhl) | S. marcescens | (shl). | Reduces the accumulation of N-acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) and shows significant inhibition of LasA protease, LasB elastase, caseinase, pyocyanin, pyoverdin, and biofilm formation. | [90] | [42] | |||||

| Bifidobacterium | B. licheniformis | DAHB1, | Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Inhibits biofilm formation in vitro and reduces shrimp intestinal colonization and mortality | [91] | [43] | ||||||

| B. licheniformis | T-1 | Aeromonas hydrophila | Quorum-quenching gene | ytnP | encodes an acyl-homoserine lactone metallo-β-lactamase | [92] | [44] | |||||

| B. longum | ATCC15707 | Escherichia coli | 0157:H7 | Inhibits AI-2 and reduces biofilm formation | [18] | |||||||

| Lactobacillus | L. acidophilus | 30SC | E. coli | O157:H7 | Inhibits AI-2 | [93] | [45] | |||||

| L. plantarum | M.2, | L. curvatus | B.67 | L. monocytogenes | Inhibits swimming motility, biofilm formation, and expression levels of target genes related to biofilm formation | [85] | [37] | |||||

| L. plantarum | SBR04MA | Microbiota of activated sludge | Inhibits N-Hexanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (6-HSL) | [94] | [46] | |||||||

| L. plantarum, | S. aureus | Reduces expression of some genes involved in biofilm formation | [95] | [47] | ||||||||

| L. acidophilus GP1B | Clostridium difficile | Reduces production of AI-2 molecules | [20] | |||||||||

| L. acidophilus | La-5 | Escherichia coli | 0157:H7 | Interferes with QS molecules and reduces adherence and colonization | [19] | |||||||

| L. acidophilus | NCFM | - | Not in pathogenic bacteria, but increases adherence of probiotic to intestinal cells by increasing AI-2 in LuxS system | [96] | [48] | |||||||

| L. brevis | 3M004 | P. aeruginosa | Inhibits biofilm formation | [97] | [49] | |||||||

| L. casei | Streptococcus mutans | Inhibits QS genes vicKR and comCD | [98] | [50] | ||||||||

| L. casei | ATCC 393, | L. reuteri | ATCC23272, | L. plantarum | ATCC14917 | L. salivarius | ATCC11741 | Streptococcus mutans | Inhibits acyl-homoserine lactone activity and blocks their synthesis | [98] | [50] | |

| L. fermentum Lim2 | Clostridium difficile | Reduces the AI-2 in QS gene | luxS | [99] | [51] | |||||||

| L. plantarum | PA 100 | P. aeruginosa | Inhibits acyl-homoserine lactone activity and blocks their synthesis | [100] | [52] | |||||||

| Streptococcus | S. salivarius | S. mutans | Inhibits biofilm formation in vitro when cultured with | S. mutans | [101] | [53] | ||||||

| S. salivarius | K12 | C. albicans | Inhibits | C. albicans | aggregation, biofilm formation, and dimorphism. | [102] | [54] | |||||

| S. salivarius | 24SMB and | S | . | oralis | 89a | S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. pyogenes, S. pneumoniae, M. catarrhalis | and | P. acnes | Inhibits biofilm formation in pathogens of the upper respiratory tract | [103] | [55] | |

References

- Nealson, K.H.; Platt, T.; Hastings, J.W. Cellular Control of the Synthesis and Activity of the Bacterial Luminescent System. J. Bacteriol. 1970, 104, 313–322.

- Verma, S.C.; Miyashiro, T. Quorum Sensing in the Squid-Vibrio Symbiosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 16386–16401.

- Padder, S.A.; Prasad, R.; Shah, A.H. Quorum sensing: A less known mode of communication among fungi. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 210, 51–58.

- Sahreen, S.; Mukhtar, H.; Imre, K.; Morar, A.; Herman, V.; Sharif, S. Exploring the Function of Quorum Sensing Regulated Biofilms in Biological Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9751.

- Qian, X.; Tian, P.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Chen, W. Quorum Sensing of Lactic Acid Bacteria: Progress and Insights. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 1–12.

- Abisado, R.G.; Benomar, S.; Klaus, J.R.; Dandekar, A.A.; Chandler, J.R. Bacterial Quorum Sensing and Microbial Community Interactions. mBio 2018, 9, e02331-17.

- Xiong, L.; Cooper, R.; Tsimring, L.S. Coexistence and Pattern Formation in Bacterial Mixtures with Contact-Dependent Killing. Biophys. J. 2018, 114, 1741–1750.

- Machado, I.; Silva, L.R.; Giaouris, E.; Melo, L.; Simões, M. Quorum sensing in food spoilage and natural-based strategies for its inhibition. Food Res. Int. 2019, 127, 108754.

- Mizan, F.R.; Jahid, I.K.; Kim, M.; Lee, K.-H.; Kim, T.J.; Ha, S.-D. Variability in biofilm formation correlates with hydrophobicity and quorum sensing among Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates from food contact surfaces and the distribution of the genes involved in biofilm formation. Biofouling 2016, 32, 497–509.

- Yuan, L.; Sadiq, F.A.; Burmølle, M.; Liu, T.; He, G. Insights into Bacterial Milk Spoilage with Particular Emphasis on the Roles of Heat-Stable Enzymes, Biofilms, and Quorum Sensing. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 1651–1660.

- Faille, C.; Bénézech, T.; Midelet-Bourdin, G.; Lequette, Y.; Clarisse, M.; Ronse, G.; Ronse, A.; Slomianny, C. Sporulation of Bacillus spp. within biofilms: A potential source of contamination in food processing environments. Food Microbiol. 2014, 40, 64–74.

- Ryu, J.-H.; Beuchat, L.R. Biofilm Formation and Sporulation by Bacillus cereus on a Stainless Steel Surface and Subsequent Resistance of Vegetative Cells and Spores to Chlorine, Chlorine Dioxide, and a Peroxyacetic Acid–Based Sanitizer. J. Food Prot. 2005, 68, 2614–2622.

- Arsene, M.M.J.; Viktorovna, P.I.; Alla, M.V.; Mariya, M.A.; Sergei, G.V.; Cesar, E.; Davares, A.K.L.; Parfait, K.; Wilfrid, K.N.; Nikolay, T.S.; et al. Optimization of Ethanolic Extraction of Enantia chloranta Bark, Phytochemical Composition, Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles, and Antimicrobial Activity. Fermentation 2022, 8, 530.

- Giaouris, E.; Heir, E.; Hébraud, M.; Chorianopoulos, N.; Langsrud, S.; Møretrø, T.; Habimana, O.; Desvaux, M.; Renier, S.; Nychas, G.-J. Attachment and biofilm formation by foodborne bacteria in meat processing environments: Causes, implications, role of bacterial interactions and control by alternative novel methods. Meat Sci. 2014, 97, 298–309.

- Borges, A.; Sousa, P.; Gaspar, A.; Vilar, S.; Borges, F.; Simões, M. Furvina inhibits the 3-oxo-C12-HSL-based quorum sensing system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and QS-dependent phenotypes. Biofouling 2017, 33, 156–168.

- Ta, C.A.K.; Arnason, J.T. Mini Review of Phytochemicals and Plant Taxa with Activity as Microbial Biofilm and Quorum Sensing Inhibitors. Molecules 2015, 21, 29.

- Skandamis, P.N.; Nychas, G.-J.E. Quorum Sensing in the Context of Food Microbiology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 5473–5482.

- Kim, Y.; Lee, J.W.; Kang, S.-G.; Oh, S.; Griffiths, M.W. Bifidobacterium spp. influences the production of autoinducer-2 and biofilm formation by Escherichia coli O157:H7. Anaerobe 2012, 18, 539–545.

- Medellin-Peña, M.J.; Griffiths, M.W. Effect of Molecules Secreted by Lactobacillus acidophilus Strain La-5 on Escherichia coli O157:H7 Colonization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 1165–1172.

- Yun, B.; Oh, S.; Griffiths, M. Lactobacillus acidophilus modulates the virulence of Clostridium difficile. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 4745–4758.

- FAO/WHO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, World Health Organization). Probiotics in Food. In Health and Nutritional Properties and Guidelines for Evaluation; FAO Food and Nutrition Paper No. 85; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization: Rome, Italy, 2002.

- Wu, M.; Dong, Q.; Ma, Y.; Yang, S.; Aslam, M.Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Potential antimicrobial activities of probiotics and their derivatives against Listeria monocytogenes in food field: A review. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111733.

- Rasch, M.; Andersen, J.B.; Nielsen, K.F.; Flodgaard, L.R.; Christensen, H.; Givskov, M.; Gram, L. Involvement of Bacterial Quorum-Sensing Signals in Spoilage of Bean Sprouts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 3321–3330.

- Grandclément, C.; Tannières, M.; Moréra, S.; Dessaux, Y.; Faure, D. Quorum quenching: Role in nature and applied developments. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 40, 86–116.

- Dong, Y.H.; Xu, J.L.; Li, X.Z.; Zhang, L.H. AiiA, an enzyme that inactivates the acylhomoserine lactone quorum-sensing signal and attenuates the virulence of Erwinia carotovora. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 3526–3531.

- Butel, M.J. Probiotics, gut microbiota and health. Médecine Mal. Infect. 2014, 44, 1–8.

- Prazdnova, E.V.; Gorovtsov, A.V.; Vasilchenko, N.G.; Kulikov, M.P.; Statsenko, V.N.; Bogdanova, A.A.; Refeld, A.G.; Brislavskiy, Y.A.; Chistyakov, V.A.; Chikindas, M.L. Quorum-Sensing Inhibition by Gram-Positive Bacteria. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 350.

- Selhub, E.M.; Logan, A.C.; Bested, A.C. Fermented foods, microbiota, and mental health: Ancient practice meets nutritional psychiatry. J. Physiol. Anthr. 2014, 33, 2.

- Arsène, M.M.J.; Davares, A.K.L.; Andreevna, S.L.; Vladimirovich, E.A.; Carime, B.Z.; Marouf, R.; Khelifi, I. The use of probiotics in animal feeding for safe production and as potential alternatives to antibiotics. Veter.-World 2021, 14, 319–328.

- Cheng, H.; Ma, Y.; Liu, X.; Tian, C.; Zhong, X.; Zhao, L. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Lactobacillus acidophilus for Treating Acute Gastroenteritis in Children. Nutrients 2022, 14, 682.

- Rodríguez-Nogales, A.; Algieri, F.; Garrido-Mesa, J.; Vezza, T.; Utrilla, M.P.; Chueca, N.; Garcia, F.; Olivares, M.; Rodríguez-Cabezas, M.E.; Gálvez, J. Differential intestinal anti-inflammatory effects of Lactobacillus fermentum and Lactobacillus salivarius in DSS mouse colitis: Impact on microRNAs expression and microbiota composition. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1700144.

- Zhao, Y.; Hong, K.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W. Lactobacillus fermentum and its potential immunomodulatory properties. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 56, 21–32.

- Gomi, A.; Iino, T.; Nonaka, C.; Miyazaki, K.; Ishikawa, F. Health benefits of fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium bifidum YIT 10347 on gastric symptoms in adults. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 2277–2283.

- Sánchez, B.; Delgado, S.; Blanco-Míguez, A.; Lourenço, A.; Gueimonde, M.; Margolles, A. Probiotics, gut microbiota, and their influence on host health and disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600240.

- Mbarga, M.J.A.; Zangue DS, C.; Ngoune, T.L.; Nyasha, K.; Louis, K. Antagonistic effects of raffia sap with probiotics against pathogenic microorganisms. Foods Raw Mater. 2021, 9, 24–31.

- Hossain, I.; Mizan, F.R.; Roy, P.K.; Nahar, S.; Toushik, S.H.; Ashrafudoulla, M.; Jahid, I.K.; Lee, J.; Ha, S.-D. Listeria monocytogenes biofilm inhibition on food contact surfaces by application of postbiotics from Lactobacillus curvatus B.67 and Lactobacillus plantarum M.2. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110595.

- Reis-Teixeira, F.B.D.; Alves, V.F.; Martinis, E.C.P.D. Growth, viability and architecture of biofilms of Listeria monocytogenes formed on abiotic surfaces. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2017, 48, 587–591.

- Meroni, G. Probiotics in Treating Pathogenic Biofilms. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17732 (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Kachhadia, R.; Kapadia, C.; Singh, S.; Gandhi, K.; Jajda, H.; Alfarraj, S.; Ansari, M.J.; Danish, S.; Datta, R. Quorum Sensing Inhibitory and Quenching Activity of Bacillus cereus RC1 Extracts on Soft Rot-Causing Bacteria Lelliottia amnigena. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 25291–25308.

- Devi, K.R.; Srinivasan, S.; Ravi, A.V. Inhibition of quorum sensing-mediated virulence in Serratia marcescens by Bacillus subtilis R-18. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 120, 166–175.

- Boopathi, S.; Vashisth, R.; Mohanty, A.K.; Jia, A.; Sivakumar, N.; Arockiaraj, J. Bacillus subtilis BR4 derived stigmatellin Y interferes Pqs-PqsR mediated quorum sensing system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Basic Microbiol. 2022, 62, 801–814.

- Nithya, C.; Aravindraja, C.; Pandian, S.K. Bacillus pumilus of Palk Bay origin inhibits quorum-sensing-mediated virulence factors in Gram-negative bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 2010, 161, 293–304.

- Algburi, A.; Zehm, S.; Netrebov, V.; Bren, A.B.; Chistyakov, V.; Chikindas, M.L. Subtilosin Prevents Biofilm Formation by Inhibiting Bacterial Quorum Sensing. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2016, 9, 81–90.

- Vinoj, G.; Vaseeharan, B.; Thomas, S.; Spiers, A.; Shanthi, S. Quorum-Quenching Activity of the AHL-Lactonase from Bacillus licheniformis DAHB1 Inhibits Vibrio Biofilm Formation In Vitro and Reduces Shrimp Intestinal Colonisation and Mortality. Mar. Biotechnol. 2014, 16, 707–715.

- Chen, B.; Peng, M.; Tong, W.; Zhang, Q.; Song, Z. The Quorum Quenching Bacterium Bacillus licheniformis T-1 Protects Zebrafish against Aeromonas hydrophila Infection. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 12, 160–171.

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Oh, S.; Song, M.; Choe, J.H.; Whang, K.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Oh, S. Influences of quorum-quenching probiotic bacteria on the gut microbial community and immune function in weaning pigs. Anim. Sci. J. 2018, 89, 412–422.

- Kampouris, I.D.; Karayannakidis, P.D.; Banti, D.C.; Sakoula, D.; Konstantinidis, D.; Yiangou, M.; Samaras, P.E. Evaluation of a novel quorum quenching strain for MBR biofouling mitigation. Water Res. 2018, 143, 56–65.

- Buck, B.; Azcarate-Peril, M.; Klaenhammer, T. Role of autoinducer-2 on the adhesion ability of Lactobacillus acidophilus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 269–279.

- Liang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, Q.; Wu, B.; Hu, M. RNA-seq-based transcriptomic analysis of AHL-induced biofilm and pyocyanin inhibition in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by Lactobacillus brevis. Int. Microbiol. 2022, 25, 447–456.

- Wasfi, R.; Abd El-Rahman, O.A.; Zafer, M.M.; Ashour, H.M. Probiotic Lactobacillus sp. inhibit growth, biofilm formation and gene expression of caries-inducing Streptococcus mutans. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 1972–1983.

- Yong, C.; Lim, J.; Kim, B.; Park, D.; Oh, S. Suppressive effect of Lactobacillus fermentum Lim2 on Clostridioides difficile 027 toxin production. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 386–393.

- Valdéz, J.C.; Peral, M.C.; Rachid, M.; Santana, M.; Perdigón, G. Interference of Lactobacillus plantarum with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in infected burns: The potential use of probiotics in wound treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2005, 11, 472–479.

- Tamura, S.; Yonezawa, H.; Motegi, M.; Nakao, R.; Yoneda, S.; Watanabe, H.; Yamazaki, T.; Senpuku, H. Inhibiting effects of Streptococcus salivarius on competence-stimulating peptide-dependent biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2009, 24, 152–161.

- Mokhtar, M.; Rismayuddin, N.A.R.; Mat Yassim, A.S.; Ahmad, H.; Abdul Wahab, R.; Dashper, S.; Arzmi, M.H. Streptococcus salivarius K12 inhibits Candida albicans aggregation, biofilm formation and dimorphism. Biofouling 2021, 37, 767–776.

- Bidossi, A.; De Grandi, R.; Toscano, M.; Bottagisio, M.; De Vecchi, E.; Gelardi, M.; Drago, L. Probiotics Streptococcus salivarius 24SMB and Streptococcus oralis 89a interfere with biofilm formation of pathogens of the upper respiratory tract. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 653.

More