Adynamic bone (ADB) is characterized by suppressed bone formation, low cellularity, and thin osteoid seams in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). There is accumulating evidence supporting increasing prevalence of ADB, particularly in early CKD. Contemporarily, it is not very clear whether it represents a true disease, an adaptive mechanism to prevent bone resorption, or just a transitional stage. In the present review, we will discuss the up-to-date knowledge of the ADB and focus on its impact on bone health, fracture risk, vascular calcification, and long-term survival. Moreover, where it will emphasize the proper preventive and management strategies of ADB. It is still unclear whether ADB is always a pathologic condition or whether it can represent an adaptive process to suppress bone resorption and further bone loss. In this article, we tried to discuss tHere, this hard topic based on the available limited information in patients with CKD will tried to be discussed.

- low bone turnover

- renal osteodystrophy

- CKD–MBD

- calcification

1. Introduction:

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global public health epidemic comprising a major overwhelming threat to bone and mineral metabolism known as chronic kidney disease- mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Almost all patients with CKD-MBD have distinct abnormal bone pathology within the spectrum of ROD, including osteitis fibrosa, adynamic bone (ADB), osteomalacia, mixed lesions, and osteoporosis (1, 2)[1][2]. ADB is primarily characterized by decreased or absent bone formation along with low cellularity of both osteoblasts and osteoclasts as well as thin osteoid seams and minimal or no peritrabecular or marrow fibrosis (3)[3].

2. Pathogenesis:

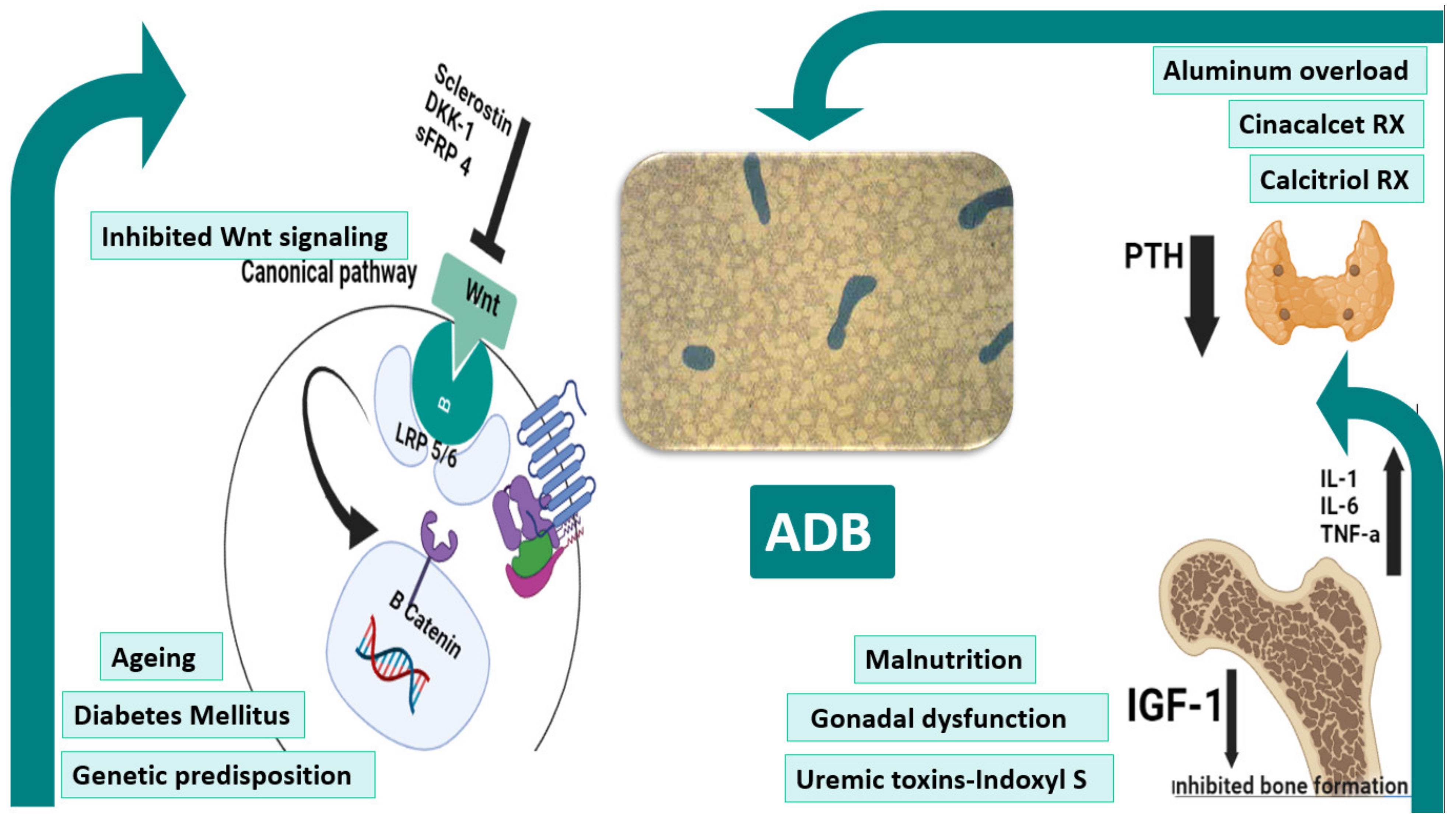

The pathophysiology of ADB is certainly multifactorial (figure 1Figure 1) comprising patient-related and iatrogenic factors on a predisposed genetic background. A state of imbalance between the low circulating levels of bone anabolic factors (e.g insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I) and the increased expression of bone turnover–inhibitory factors, such as sclerostin, and Dickkopf-related protein-1 (Dkk-1), largely predominates. This imbalance ultimately suppresses bone formation through repression of WNT/β-catenin signaling (4)[4]. Moreover, uremic toxins may play a role in this setting. In addition, diabetes, malnutrition and gonadal dysfunction may play a role.

Figure (1): Pathogenesis of ADB. Ageing, diabetes, genetic factors underlie the pathogenesis of ADB. Scelorstin, DKK1, and sFRP4 inhibits the extracellular binding of wnt to the Frz-LRP5/6 receptor complex blocking the B-catenin mediated expression of target genes. Hypoparathyrodism precipitated by excessive treatment with cinacalcet and calcitriol therapies together with uremic milieus such as malnutrition, gonadal dysfunction and uremic toxins all predispose to ADB. The central figure shows acellular bone with bone volume in a patient with ADB. ADB: adynamic bone, DKK-1: Dickkopf-related protein-1, IGF-1: insulin like growth factor-1, IL-1: interleukin-1, IL-6: interleukin-6, LRP5/6: Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6, PTH: parathyroid hormone, sFRP 4: Secreted frizzled-related protein 4, TNF-a: tumor necrosis factor-a.

3. Impact of LBT on bone hBone Health/fFracture, oOsteoporosis, and mMortality:

Adynamic bone results in poor skeletal health, bone fragility and diminished ability to restore damaged bone (5)[5]. A crucial aspect of delayed remodeling is that it promotes more secondary mineralization, making the bone stiffer/tougher (6)[6]. However, in the long term, over mineralization can induce a brittle bone that increases the risk of atypical fractures (7)[7]. Moreover, suppression of bone turnover may cause microcracks which are difficult to heal in presence of low bone formation (8)[8]. Several studies have reported a J- or U-shaped association between PTH levels and mortality in patients on dialysis from different geographic areas (9-15)[9][10][11][12][13][14][15]. Several studies concluded that low PTH levels, indicative of LBT, were associated with higher risk of mortality (16, 17)[16][17].

4. ADB as a risk fAs A Risk Factor for vVascular cCalcification:

Cardiovascular disease is considered the main cause of death in the CKD population (18)[18]. VC is common in CKD, in both pre dialysis and dialysis patients, and it has been linked to the high CKD-related cardiovascular mortality (19)[19]. ADB leads to reduced bone capacity to buffer calcium and inability to handle an extra calcium load (20)[20]. Experimental studies have demonstrated the crucial role of increased levels of calcium and phosphate and the importance of bone turnover on uremic VC (19, 21)[19][21]. Several clinical studies have investigated the possible association between LBT and VC in CKD (22-24)[22][23][24].

5. Diagnosis:

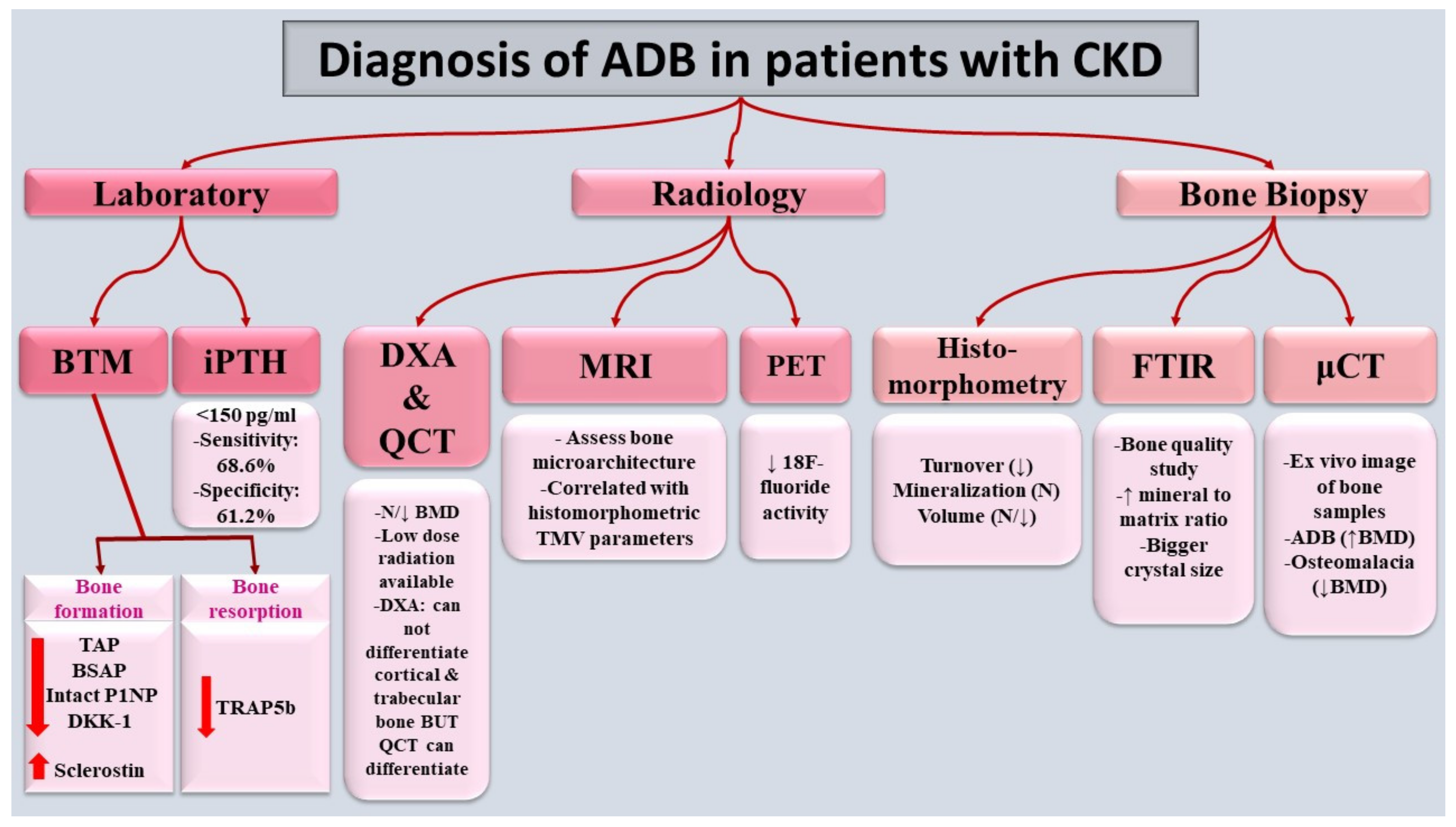

Despite that bone biopsy is the gold standard method for the diagnosis of ADB, non-invasive tools can help not only to diagnose ADB but also to follow up the response to the pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions (figure 2Figure 2).

Figure (2): Diagnosis of ADB in patients with CKD. Diagnosis mainly relies on bone biopsy, gold standard, as well as reduced bone formation & bone resorption markers. ADB: adynamic bone, BSAP: bone specific alkaline phosphatase, BMD: bone mineral density, BTM: bone turnover markers, CKD: chronic kidney disease, DKK-1: Dickkopf-related protein-1, DXA: Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, FTIR: Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, iPTH: intact parathyroid hormone, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging, P1NP: Procollagen type 1 N-terminal pro peptide, PET: Positron emission tomography,QCT: Quantitative computed tomography, TAP: total alkaline phosphatase, TMV: turnover/mineralization/volume, TRAP 5B: tartrate resistant acid phosphatase 5b, μCT: Micro-Computed Tomography

6. Prevention and tTreatment of ADB in CKD

Despite the underlying complex pathophysiology of ADB, its management is based mainly on the avoidance of risk factors associated with reduction of bone turnover, such as aluminum exposure, oversuppression of PTH secretion due to calcium overload, administration of high doses of vitamin D analogs and/or calcimimetics. Moreover, factors that may contribute to PTH resistance, such as hyperphosphatemia, malnutrition, inflammation, and progression of CKD, among others, should also be targeted (25, 26)[25][26]. Antiresorptives which can potentially used in treatment of ADB are shown in table 1Table 1.

Table 1: Osteo-anabolics used for treatment of ADB

|

Drugs |

Mechanism of action |

Main studies |

Results |

|

|

Teriparatide (PTH 1–34) |

- A recombinant form of PTH, consisting of amino acids 1-34 that binds to PTH type 1 receptor stimulating osteoblast activity |

- Mitsopoulos et al.: 9 hemodialysis patients; 48 weeks of therapy (27).[27]. |

With teriparatide: -Improvement of BMD (femoral neck: 2.7%; lumbar: 4.9%). |

|

|

- Cejka et al.: 7 patients with ADB, 6-month therapy (28).[28].

|

With teriparatide: -Improvement of BMD at lumbar spine. -No changes of BMD at femoral neck, bone turnover markers, or CAC. |

|||

|

- Sumida et al.: 22 patients on dialysis; dose 56.5 μg once-weekly for 48 weeks (29).[29]. |

With teriparatide: -High rate of discontinuation (50%) due to transient hypotension. - Improvement of BMD at lumbar spine by 3.3% and 3.0% at weeks 24 and 48. -No change in the BMD at femoral neck and distal radius. |

|||

|

Abaloparatide |

- Fragment of parathyroid hormone-related peptide |

- Miller et al.: ACTIVE was phase 3, double blinded, RCT included 1645 postmenopausal women who received daily SC 80 μg abaloparatide or placebo) (30).[30]. |

With abaloparatide: Improvement of BMD at 1.5 years: - At total hip by 4.18% - At femoral neck by 3.6% - At lumber spine by 11.2% |

|

|

Bilezikian et al: Post hoc analysis of ACTIVE to evaluate safety and efficacy of abaloparatide in patients with different kidney functions (31).[31]. |

With abaloparatide: Improvement of BMD at 1.5 years: - At lumbar spine by 9.91% in patients with eGFR <60 mL/min. - At femoral neck by 3.06% in patients with eGFR <60 mL/min. |

|||

|

Romosozumab |

- Sclerostin humanized monoclonal antibody - Has anabolic properties |

Miller et al: Post hoc analysis of FRAME and ARCH trials. FRAME included 7147 osteoporotic postmenopausal women who received 210 mg SC romosozumab or monthly placebo and ARCH (received monthly 210 mg SC romosozumab or weekly 70 mg oral alendronate) enrolled 4077 postmenopausal females with osteoporosis and fragility fractures. (32).[32]. |

With romosozumab In FRAME: Improvement of BMD at 1 year: - At lumbar spine by 13% and 10.9% in patients with mild and moderate CKD, respectively. - At total hip by 5.9% and 5.2% in patients with mild and moderate CKD, respectively. - At femoral neck by 5.3% and 4.6% in patients with mild and moderate CKD, respectively. In ARCH: Improvement of BMD at 1 year: At lumbar spine by 8.8% and 8.1% in patients with mild and moderate CKD, respectively. - At total hip by 3.2% and 3% in patients with mild and moderate CKD, respectively. - At femoral neck by 3.2% and 2.7% in patients with mild and moderate CKD, respectively. |

|

|

Sato et al.: included 76 HD patients with high risk of fractures received SC monthly 210 mg romosozumab and 55 HD untreated patients (33).[33]. |

With romosozumab: -Improvement of BMD at lumber spine at 1 year by 15.3% -Improvement of BMD at femoral neck at 1 year by 7.2% |

|||

|

Ronacaleret |

- Calcium sensing receptor antagonist - Calcilytic - Increase endogenous production of PTH |

Fitzpatrick et al: placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial. 569 women with post-menopausal osteoporosis, teriparatide 20 µg SC once daily or ronacaleret 100 mg, 200 mg, 300 mg, or 400 mg once daily, alendronate 70 mg once weekly, or matching placebos in a double-blind fashion. (34).[34]. |

- Improvement of spine integral vBMD (0.49% to 3.9%) - Improvement of trabecular vBMD (1.8% to 13.3%). - Non-dose dependent decrease (1.79%) in integral vBMD at proximal femur |

|

ACTIVE: The Abaloparatide Comparator Trial In Vertebral Endpoints, ARCH: Active-Controlled Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis at High Risk, BMD: bone mineral density, CAC: coronary artery calcification, CKD: chronic kidney disease, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, FRAME: Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis, HD: hemodialysis, PTH: parathyroid hormone, RCT: randomized clinical trial, SC: subcutaneous, vBMD: volumetric bone mineral density

Conclusion:

7. Conclusion:

ADB prevalence has been increasing in CKD, including in dialysis patients. It involves multiple pathogenetic mechanisms and risk factors. Its diagnosis depends mainly on bone

biopsy in addition to non-invasive biomarkers. It is still unknown whether all cases of ADB are maladaptive or whether it can be adaptive/compensatory in certain situations.

Management of ADB relies generally on prevention and treatment of its risk factors as well as use of osteo-anabolic medications.

References

- Malluche, H.H.; Mawad, H.W.; Monier-Faugere, M.C. Renal osteodystrophy in the first decade of the new millennium: Analysis of 630 bone biopsies in black and white patients. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011, 26, 1368–1376.

- Ketteler, M.; Block, G.A.; Evenepoel, P.; Fukagawa, M.; Herzog, C.A.; McCann, L.; Moe, S.M.; Shroff, R.; Tonelli, M.A.; Toussaint, N.D. Diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder: Synopsis of the kidney disease: Improving global outcomes 2017 clinical practice guideline update. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 168, 422–430.

- Dempster, D.W.; Compston, J.E.; Drezner, M.K.; Glorieux, F.H.; Kanis, J.A.; Malluche, H.; Meunier, P.J.; Ott, S.M.; Recker, R.R.; Parfitt, A.M. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: A 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 2.

- Tomiyama, C.; Carvalho, A.B.; Higa, A.; Jorgetti, V.; Draibe, S.A.; Canziani, M.E.F. Coronary calcification is associated with lower bone formation rate in CKD patients not yet in dialysis treatment. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 499–504.

- London, G.M.; Marty, C.; Marchais, S.J.; Guerin, A.P.; Metivier, F.; de Vernejoul, M.-C. Arterial calcifications and bone histomorphometry in end-stage renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 1943–1951.

- Hernandes, F.R.; Canziani, M.E.F.; Barreto, F.C.; Santos, R.O.; Moreira, V.d.M.; Rochitte, C.E.; Carvalho, A.B. The shift from high to low turnover bone disease after parathyroidectomy is associated with the progression of vascular calcification in hemodialysis patients: A 12-month follow-up study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174811.

- Andreoli, S.P.; Bergstein, J.M.; Sherrard, D.J. Aluminum intoxication from aluminum-containing phosphate binders in children with azotemia not undergoing dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984, 310, 1079–1084.

- Ward, M.; Ellis, H.; Feest, T.; Parkinson, I.; Kerr, D.; Herrington, J.; Goode, G. Osteomalacic dialysis osteodystrophy: Evidence for a water-borne aetiological agent, probably aluminium. Lancet 1978, 311, 841–845.

- Coen, G.; Mazzaferro, S.; Ballanti, P.; Sardella, D.; Chicca, S.; Manni, M.; Bonucci, E.; Taggi, F. Renal bone disease in 76 patients with varying degrees of predialysis chronic renal failure: A cross-sectional study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1996, 11, 813–819.

- Dukas, L.; Schacht, E.; Stähelin, H.B. In elderly men and women treated for osteoporosis a low creatinine clearance of< 65 ml/min is a risk factor for falls and fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 2005, 16, 1683–1690.

- Malluche, H.; Monier-Faugere, M.-C. Renal osteodystrophy: What’s in a name? Presentation of a clinically useful new model to interpret bone histologic findings. Clin. Nephrol. 2006, 65, 235–242.

- Moe, S.; Drüeke, T.; Cunningham, J.; Goodman, W.; Martin, K.; Olgaard, K.; Ott, S.; Sprague, S.; Lameire, N.; Eknoyan, G. Kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO). Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 1945–1953.

- Hutchison, A.J.; Whitehouse, R.W.; Boulton, H.F.; Adams, J.E.; Mawer, E.B.; Freemont, T.J.; Gokal, R. Correlation of bone histology with parathyroid hormone, vitamin D3, and radiology in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 1993, 44, 1071–1077.

- Sherrard, D.J.; Hercz, G.; Pei, Y.; Maloney, N.A.; Greenwood, C.; Manuel, A.; Saiphoo, C.; Fenton, S.S.; Segre, G.V. The spectrum of bone disease in end-stage renal failure—an evolving disorder. Kidney Int. 1993, 43, 436–442.

- Drüeke, T.B.; Massy, Z.A. Changing bone patterns with progression of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2016, 89, 289–302.

- Sprague, S.M.; Bellorin-Font, E.; Jorgetti, V.; Carvalho, A.B.; Malluche, H.H.; Ferreira, A.; D’Haese, P.C.; Drüeke, T.B.; Du, H.; Manley, T. Diagnostic accuracy of bone turnover markers and bone histology in patients with CKD treated by dialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 67, 559–566.

- Barreto, F.C.; Barreto, D.V.; Moyses, R.M.A.; Neves, K.; Canziani, M.E.F.; Draibe, S.A.; Jorgetti, V.; Carvalho, A.B.D. K/DOQI-recommended intact PTH levels do not prevent low-turnover bone disease in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 771–777.

- Massy, Z.; Drueke, T. Adynamic bone disease is a predominant bone pattern in early stages of chronic kidney disease. J. Nephrol. 2017, 30, 629–634.

- Barreto, F.C.; Barreto, D.V.; Canziani, M.E.F.; Tomiyama, C.; Higa, A.; Mozar, A.; Glorieux, G.; Vanholder, R.; Massy, Z.; Carvalho, A.B.D. Association between indoxyl sulfate and bone histomorphometry in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients. Braz. J. Nephrol. 2014, 36, 289–296.

- El-Husseini, A.; Abdalbary, M.; Lima, F.; Issa, M.; Ahmed, M.-T.; Winkler, M.; Srour, H.; Davenport, D.; Wang, G.; Faugere, M.-C. Low turnover renal osteodystrophy with abnormal bone quality and vascular calcification in patients with mild-to-moderate CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 2022, 7, 1016–1026.

- Amr El-Husseini, M.M.A.; Issa, M.; Winkler, M.; Lima, F.; Faugere, M.; Srour, H.; Malluche, H.H. Progression of Renal Osteodystrophy and Vascular Calcifications in Patients with CKD Stage II-IV. In Kidney Week 2021; ASN: Orlando, FL, USA, 2021.

- Malluche, H.H.; Ritz, E.; Lange, H.P.; Kutschera, L.; Hodgson, M.; Seiffert, U.; Schoeppe, W. Bone histology in incipient and advanced renal failure. Kidney Int. 1976, 9, 355–362.

- Hernandez, D.; Concepcion, M.T.; Lorenzo, V.; Martinez, M.E.; Rodriguez, A.; De Bonis, E.; Gonzalez-Posada, J.M.; Felsenfeld, A.J.; Rodriguez, M.; Torres, A. Adynamic bone disease with negative aluminium staining in predialysis patients: Prevalence and evolution after maintenance dialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 1994, 9, 517–523.

- Torres, A.; Lorenzo, V.; Hernández, D.; Rodríguez, J.C.; Concepción, M.T.; Rodríguez, A.P.; Hernández, A.; de Bonis, E.; Darias, E.; González-Posada, J.M.; et al. Bone disease in predialysis, hemodialysis, and CAPD patients: Evidence of a better bone response to PTH. Kidney Int. 1995, 47, 1434–1442.

- Monier-Faugere, M.C.; Malluche, H.H. Trends in renal osteodystrophy: A survey from 1983 to 1995 in a total of 2248 patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 1996, 11 (Suppl. 3), 111–120.

- Araújo, S.M.; Ambrosoni, P.; Lobão, R.R.; Caorsi, H.; Moysés, R.M.; Barreto, F.C.; Olaizola, I.; Cruz, E.A.; Petraglia, A.; Dos Reis, L.M.; et al. The renal osteodystrophy pattern in Brazil and Uruguay: An overview. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2003, S54–S56.

- Barreto, D.V.; Barreto Fde, C.; Carvalho, A.B.; Cuppari, L.; Draibe, S.A.; Dalboni, M.A.; Moyses, R.M.; Neves, K.R.; Jorgetti, V.; Miname, M.; et al. Association of changes in bone remodeling and coronary calcification in hemodialysis patients: A prospective study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2008, 52, 1139–1150.

- Carbonara, C.E.M.; Reis, L.M.D.; Quadros, K.; Roza, N.A.V.; Sano, R.; Carvalho, A.B.; Jorgetti, V.; Oliveira, R.B. Renal osteodystrophy and clinical outcomes: Data from the Brazilian Registry of Bone Biopsies—REBRABO. J. Bras. Nefrol. 2020, 42, 138–146.

- Neto, R.; Pereira, L.; Magalhaes, J.; Quelhas-Santos, J.; Martins, S.; Carvalho, C.; Frazao, J.M. Sclerostin and DKK1 circulating levels associate with low bone turnover in patients with chronic kidney disease Stages 3 and 4. Clin. Kidney J. 2021, 14, 2401–2408.

- Jørgensen, H.S.; Behets, G.; Viaene, L.; Bammens, B.; Claes, K.; Meijers, B.; Naesens, M.; Sprangers, B.; Kuypers, D.; Cavalier, E.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Noninvasive Bone Turnover Markers in Renal Osteodystrophy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 79, 667–676.e1.

- Hirata, J.; Hirai, K.; Asai, H.; Matsumoto, C.; Inada, M.; Miyaura, C.; Yamato, H.; Watanabe-Akanuma, M. Indoxyl sulfate exacerbates low bone turnover induced by parathyroidectomy in young adult rats. Bone 2015, 79, 252–258.

- Mozar, A.; Louvet, L.; Godin, C.; Mentaverri, R.; Brazier, M.; Kamel, S.; Massy, Z.A. Indoxyl sulphate inhibits osteoclast differentiation and function. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2012, 27, 2176–2181. [Google Scholar]

- Shyu, J.F.; Liu, W.C.; Zheng, C.M.; Fang, T.C.; Hou, Y.C.; Chang, C.T.; Liao, T.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Lu, K.C. Toxic Effects of Indoxyl Sulfate on Osteoclastogenesis and Osteoblastogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11265.

- Le Meur, Y.; Lorgeot, V.; Aldigier, J.C.; Wijdenes, J.; Leroux-Robert, C.; Praloran, V. Whole blood production of monocytic cytokines (IL-1beta, IL-6, TNF-alpha, sIL-6R, IL-1Ra) in haemodialysed patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 1999, 14, 2420–2426