Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is an invasive epithelial neoplasm that is influenced by various risk factors, with a low survival rate and an increasing death rate. In the past few years, with the verification of the close relationship between different types of cancers and the microbiome, research has focused on the compositional changes of oral bacteria and their role in OSCC. Generally, oral bacteria can participate in OSCC development by promoting cell proliferation and angiogenesis, influencing normal apoptosis, facilitating invasion and metastasis, and assisting cancer stem cells. The study findings on the association between oral bacteria and OSCC may provide new insight into methods for early diagnosis and treatment development.

- Oral squamous cell carcinoma

- oral bacteria

- inflammation

1. Introduction

Oral cancer is one of the major malignant tumors of the head and neck region, causing great mortality and morbidity [1][2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are around 657,000 new cases of oral cavity and pharyngeal cancers each year, with more than 330,000 deaths. Oral squamous cell carcinoma(OSCC), an invasive epithelial neoplasm with different degrees of differentiation, accounts for about 90% of oral cancer. It starts with the accumulation of genetic mutations and specific genetic variations in oncogenes and suppressor genes[3] .The high-risk areas are the floor of the mouth and the ventrolateral tongue, while the low-risk regions lie in the palatal mucosa and the tongue dorsum [4].

The key to OSCC management is early diagnosis and treatment. Targeting pre-malignant oral diseases has been regarded as a possible strategy for the early diagnosis of at-risk and high-risk patients, but it remains difficult to diagnose clinically [5][6].The most common treatment for OSCC is surgical resection, but radiotherapy and chemotherapy are used preoperatively and postoperatively to reduce difficulties in surgical removal or eliminate remaining cancer cells [7][8]. An epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibody has been developed, aimed at decreasing the over-expression of EGFR,which has been associated with the poor prognosis of OSCC patients [9]. However,despite more diverse and advanced treatment options, the five-year survival rate remains below 50% [10][11][12].

OSCC is influenced by various factors, including tobacco smoking, alcohol abuse, HPV (human papillomavirus) infection,male gender, economic status, dietary habits, and oral hygiene [13][14][15][16]. Lately, studies haveverified a close link between OSCC and oral bacteria, which may provide a fresh view and new potentialtargets for OSCC diagnosis and treatment [17][18][19].

The oral bacteria are the second-largest human-associated microbial community, only exceeded by bacteria in the gut, and constitute a unique micro-ecology in the oral cavity. More than 700 bacterial species survive in it, along with archaea, fungi, and viruses. In the normal oral cavity, bacteria react with each other but maintain a good balance so that oral health can be achieved. However, when something breaks the balance, dysbiosis occurs and the healthy, balanced oral ecosystem is destroyed. Oral pathogens take advantage of the imbalance, leading to diseases such as caries and periodontal disease [20][21]. Lately, many studies have demonstrated that oral bacteria could also be important during the process of OSCC by exploring changes in the abundance of oral bacteria and mechanisms that might participate in the development of cancer . Bacterial compositional differences have been demonstrated among cancer patients, normal individuals, and pre-cancer patients [22][23]. Other studies have verified the potential mechanisms by which oral bacteria affect the development of OSCC, including speeding up cell proliferation, inhibiting apoptosis, and improving tumor invasion and metastasis [24].

This review summarizes the compositional changes in bacteria in OSCC patients and the possible mechanisms associated with oral cancer development, hoping to reveal the hidden link between certain oral bacteria and OSCC and provide new sight into the prevention, prediction, and treatment of oral cancer.

2. Compositional Variations in Oral Bacteria in OSCC

Over the past 10 years, several studies have taken fresh perspectives on the variations in oral bacteria associated with OSCC and their analyses showed similarities and differences. Using 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing to compare oral bacterial DNA isolated from cancer patients and normal subjects, the findings revealed comprehensive relationships between OSCC and oral bacteria

[25].

.

Pathogenic periodontal bacteria are a group of bacteria associated with periodontal diseases and contribute to an inflammatory state, which may induce DNA damage in epithelial cells in cancer progression. Periodontal pathogenic bacteria have been associated with a higher risk for OSCC and

Fusobacterium

,

Peptostreptococcus

,

Filifactor

,

Parvimonas

,

Pseudomonas

,

Campylobacter

, and

Capnocytophaga

were reported in significantly high abundance in OSCC patients. Moreover, proinflammatory substances secreted by periodontal pathogenic bacteria such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were enriched in cancer samples

[26]

. Among the bacteria,

Fusobacterium

showed the most verified alterations in cancerous lesions. In a group of cancer patients,

Fusobacterium

showed a significant increase in abundance, especially in stage 4 patients

. Moreover, some research suggested that

Fusobacterium

might be an essential part of the bacterial impact on OSCC since it had the ability to co-adhere with other species and form an association network centered around itself in patients of the cancer group

[29]

.

Peptostreptococcus

,

Parvimonas,

and

Campylobacter

are anaerobic bacteria reported to participate in the colorectal cancer process

. Two other genera,

Filifactor

and

Capnocytophaga

,have been closely linked to lung cancer

. Nevertheless, how they are involved in OSCC is still unclear, thus, further studies are required.

Pseudomonas

has not been linked to cancer yet, but it possesses virulence factors such as LPS and flagella, which play roles in carcinogenesis by counteracting host defenses and causing direct damage to host tissues

[34]

. In addition,

P. aeruginosa

could injure epithelial cells by triggering DNA strand breaks

[35]

. Therefore, we believe that the ability of periodontal pathogens, particularly

Fusobacterium nucleatum

, to aggregate and induce inflammation, which may cause DNA damage to epithelial cells leading to cancer progression, might account for the compositional change in bacteria in tumor sites.

Periodontal pathogenic bacteria appeared to be positively associated with OSCC, however, other bacteria have shown different changes.

Firmicutes

(especially

Streptococcus

) and

Actinobacteria

(especially

Rothia

) comprised a smaller proportion of the bacteria in OSCC tissues and were enriched in the healthy group.

Streptococcus

was linked to

F. nucleatum

in some aspects

. On one hand,

Streptococcus

is an early colonizer but

F. nucleatum

is a transitional bacteria between early and late colonizers in the OSCC process, with an ability to co-aggregate. On the other hand,

Streptococcus

could attenuate the proinflammatory responses of oral epithelial cells induced by

F. nucleatum

. Moreover,

Firmicutes

and

Actinobacteria

both were confirmed to have a negative correlation with oral pre-cancer, suggesting that

Firmicutes

and

Actinobacteria

may be altered early in cancer development

[38]

. Thus, we believe that

Firmicutes

and

Actinobacteria

are sensitive to cancer-related circumstances, and a remarkably decreased proportion of these bacteria along with an increased proportion of

F. nucleatum

may indicate a pre-cancerous or cancerous state.

Besides

Firmicutes

and

Actinobacteria

, some research identified alterations in other oral bacteria in oral pre-cancerous conditions and differences between normal, pre-cancerous, and cancerous lesions.

Megasphaera micronuciformis

,

Prevotella melaninogenica,

and

Prevotella veroralis

were found more abundant in oral pre-cancer.

M. micronuciformis

seemed to be the best candidate for a specific biomarker as it was detected only in the pre-cancer group

[39]

. In addition, five genera, including

Bacillus, Enterococcus, Parvimonas, Peptostreptococcus,

and

Slackia

, displayed distinct differences in abundance between patients with epithelial precursor lesions and cancer patients. It takes a long time to change from a pre-cancerous state to cancer. Therefore, bacterial changes at this stage may be a potential target for primary prevention. Furthermore, specific microbial combinations have been investigated as potential markers for OSCC diagnosis and demonstrated considerable accuracy. In 2017, Zhao et al. claimed that a highly connected bacterial cluster of

Fusobacterium

comprising seven operational taxonomic units (OTUs) showed considerable predictive power in OSCC since the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve(AUC) reached 0.866. Another study conducted in 2018 by Yang et al. reported that a bacterial combination consisting of

Fusobacterium periodonticum

,

Streptococcus mitis

, and

Porphyromonas pasteri

had an AUC of 0.956 (95% CI: 0.925–0.986) in discriminating OSCC stage 4 from healthy controls. Moreover, in 2017, Lee et al. concluded that

Bacillus

,

Enterococcus

,

Parvimonas

,

Peptostreptococcus

, and

Slackia

in saliva might be a group of potential biomarkers for OSCC diagnosis. However,certain components of this marker are not officially accepted for diagnosis and prognosis despite its accuracy. Further studies are still needed to explore how oral bacteria act upon tumors and the converse situation.

The most recent 10-year research findings have reported changes in oral bacteria in OSCC (Table A1). However, a complete consensus has not been reached. Different specimen types, controls, and methods might have contributed to the lack of consensus. Apart from these factors, disparate stages studied in OSCC may also be contributors to the inconsistent findings. In the progression from normal epithelial tissue to pre-malignant and subsequently cancerous lesions, the proportion of oral bacteria synchronously changes and the bacteria that adapt to or facilitate the tumor microenvironment at different phases become dominant. Here, we choose to introduce the so-called “drive-passengers” model to explain this phenomenon

. The “drivers” are defined as oral bacteria with pro-carcinogenic features such as the production of DNA-damaging compounds that might initiate oral cancer. For this reason, drivers emerge at early cancer stages.

Porphyromonas gingivalis

may be a driver since it can influence pathways related to DNA damage and directly damage DNA with its LPS, a potent inflammatory molecule with cancer-promoting properties

. Furthermore, in studies using high-throughput sequencing technology, a remarkable change in the abundance of

P. gingivalis

in OSCC has been reported and it seems to occur most in the very early stage of OSCC. The passengers are said to be inhibited in a healthy oral state, but when dysbiosis occurs, such as in a cancer-related state, the passengers will have a competitive advantage in the tumor microenvironment. This kind of bacteria participates in the progression and promotion of tumors. From our point of view,

F. nucleatum

may be a vital passenger. The basis for this hypothesis is that

F. nucleatum

remains in low proportion in oral healthy cavities, but it increases significantly and seems to be the most prevalent in OSCC patients

[44]

. Moreover, it has been mentioned in regard to obvious compositional changes in oral cancer in most articles and reported to participate in the progression of OSCC by accelerating the proliferation of cancer cells and helping cancer cells to invade and metastasize

. Therefore,

F. nucleatum

could represent a signal for the malignant transformation of oral epithelial cells.

Moreover, compared with the inconsistent compositional alterations reported, functional changes in oral bacteria in OSCC may be more reliable. Several findings in the last two years demonstrated that the bacteria found within OSCC tissue were functionally proinflammatory

[49]

, and LPS as well as peptidases, two proinflammatory substances from bacteria, were enriched in OSCC samples.Meanwhile, a study that focused on the functional prediction of oral bacterial communities also revealed a potent enrichment in the genes involved in bacterial chemotaxis and flagellar assembly in cancer-related inflammation.

3. Mechanism of the Effect of Oral Bacteria on OSCC

OSCC is a malignant tumor originating from oral epithelial

. Furthermore, like other malignant tumors, it develops through the successive progression of various features and mechanisms such as the activation of oncogenes, the inhibition of cancer cell apoptosis, the promotion of invasiveness and metastasis, and changes in the tumor microenvironment

. The tumor microenvironment consists of the extracellular matrix, soluble molecules, and tumor stromal cells, which interact with a community of heterotypic cells

[53]

. roinflammatory factors in the tumor microenvironment are part of the final outcome of a dynamic process that includes the chemotaxis of immune cells and the appearance of cytokines and chemokines in the tumor microenvironment, which are always over-expressed

. They cause a series of reactions that help tumor cells develop, and with the progression of the tumors, proinflammatory factors increase as well. Moreover, similar to the progression of other tumors, tumorigenesis, and tumor development is an on-going process, which means that cancer cells grow faster and show direct metastasis over wide ranges.

Recently, based on compositional alterations in oral bacteria during OSCC progression, numerous experiments have explored the probable mechanisms explaining how oral bacteria affect oral cancer. From a retrospective view of previous studies, although the bridges linked to cancer are diverse, the focus seems to be on the chronic inflammation involved in tumorigenesis and tumor progression

. Below are different mechanisms involved in the relationship between oral bacteria and OSCC, and among them, some mechanisms are associated with inflammation.

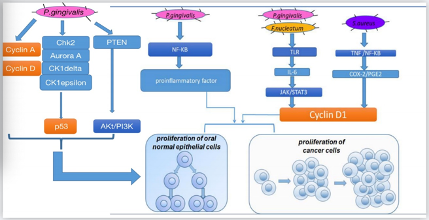

3.1. Cell Proliferation

There are several pathways for different oral bacteria to promote cell proliferation (Figure 1). In vitro, oral bacteria such as

P. gingivalis

can lead to secondary impacts on the proliferation rate by modifying the expression levels of oncogenic-relevant α-defensin genes. Hoppe et al. incubated oral tumor cells with

P. gingivalis

and human α-defensins and observed a noticeable increase in tumor cell proliferation

[58]

. Similarly, another study conducted in the human squamous cell carcinoma cell line SCC-25 and primary human gingival keratinocytes revealed that, in both cells,

P. gingivalis

and its membrane fraction regulated some genes involved in the downstream signaling pathway of the proinflammatory active transcription factor NF-κB and some members of the MAPK family such as MAPK14 (p38), MAPK8 (JNK1), and NFKB1(p50), which participated in cancer proliferation and control. Moreover, Kuboniwa et al. co-cultured 50% confluent human oral epithelial cell culture cells with

P. gingivalis

strains at 37 °C and 5% CO

2

and demonstrated that

P. gingivalis

infection affected pathways related to cyclins, p53, and PI3K that exerted control over the cell cycle [43]. By regulating cyclin A and cyclin D, two nuclear proteins

[59]

,

P. gingivalis

assisted gingival epithelial cells to progress through the G1 phase at a faster pace. By downregulating kinases such as Chk2, aurora A, CK1delta, and CK1epsilon to make p53, a suppressor that could arrest the cell cycle unstable and inactivate,

P. gingivalis

accelerated cell proliferation

. By downregulating PTEN, a lipid phosphatase that prevents the activation of Akt,

P. gingivalis

improved the levels of PI3K and phosphoinositide-dependent protein-serine kinase 1 (PDK1) activated by Akt, which promoted cell proliferation

. In addition, a study our team participated in found that when human oral keratinocyte cells were infected with inactivated

Staphylococcus aureus

in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, certain

S. aureus

genes upregulated COX-2 transcription, increased PGE2 production, andthen induced higher expression of oral cancer-associated genes cyclin D1, which is associated with cell proliferation and growth regulation. Combined with earlier studies on the relationship between OSCC and COX-2/PGE2,

S. aureus

is another likely vital bacterial candidate involved in cancer

. Other research in vivomouse model and in vitroSCC-25 and CAL 27 human tongue SCC cell lines focusing on

P. gingivalis

and

F. nucleatum

observed the same results that by triggering Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling, IL-6 production increased, and then activated STAT3, which induced important effectors such as cyclinD1, driving cancer cells to grow.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms for how oral bacteria promote cell proliferation.

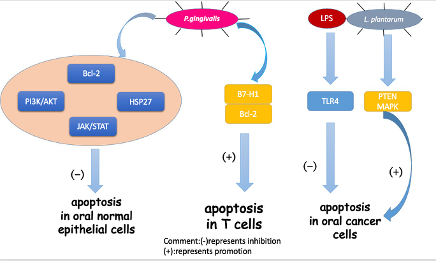

3.2. Cell Apoptosis

Apoptosis is a certain programmed cell death process that is a vital part of the immune system. It serves as a tumor suppressor in various cancer phases

. Based on recent studies, apoptosis in OSCC was associated with oral bacteria and different bacteria showed distinct impacts on apoptosis (Figure 2).

The representative oral pathogen,

P. gingivalis

, has been mostly studied. Not only can

P.gingivalis

inhibit the apoptosis of oral epithelial cells, but the bacteria can also induce the apoptosis of immune cells to help protect cancer cells from an immune attack. In oral epithelial cells, by increasing phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling

and modulating Bcl-2 family proteins,

P. gingivalis

infection could improve the survival and proliferation of gingival epithelial cells (GECs), indirectly inhibiting intrinsic apoptosis. Moreover, a homolog of a conserved nucleoside-diphosphate-kinase (Ndk) family of multifunctional enzymes and secreted molecule of

P. gingivalis

inhibited apoptosis in GECs via phosphorylating HSP27, a kind of heat shock proteinthat inhibits apoptosis

.Another pathway for

P. gingivalis

toinhibit apoptosis in GECs was through the manipulation of the JAK/STAT pathway, which controls the intrinsic mitochondrial cell death pathways

[73]

.In immune cells, Groeger et al. analyzed squamous carcinoma SCC-25 cells after infection with two virulent

P. gingivalis

strains (

P. gingivalis

strains W83and ATCC 33277) and a commensal bacterium(

Streptococcus salivarius K12

). The results showed that only

P. gingivalis

could activate (B7-H1) receptors, which led to anergy and the apoptosis of activated T cells and helped cancer cells evade immune attack

[74]

.

In the last few years, besides the mechanism mentioned above, triggered TLR signaling has been observed in oral tumorigenesis

. Although TLRs work mainly in immunity, some studies have reported their role in inhibiting apoptosis in cancer cells

. Lately, TLR2 and TLR4 were studied for their capacity to recognize different pathogens from bacteria. Recently, a group conducted a research based on the hypothesis that bacterial pathogens such as

P. gingivalis

and

F. nucleatum

may induce resistance to apoptosis by activating TLR2

[81]

. They analyzed the expression of TLR-2 in clinical OSCC specimens and human OSCC-derived cell lines (HSC). They demonstrated that TLR2 was highly expressed in OSCC compared to the adjacent non-malignant tissue. They also found that the activation of TLR-2 could induce miR-146a-5p expression, causing suppression of the downstream molecule CARD10, which is recognized as a molecule regulating apoptosis and may function as a pro-apoptotic molecule by mediating the assembly of larger protein complexes in OSCC

[82]

. Consequently, CARD10 suppression resulted in the resistance to cisplatin-induced cell death and apoptosis in OSCC cells. Cisplatin, a commonly used chemotherapy drug, interferes with DNA replication, which kills the fastest proliferating cells

[83]

. Previously, TLR4 was reported to have a similar effect in OSCC activated by LPS, an endotoxin secreted by gram-negative bacteria in the oral cavity

[84]

. Moreover, the study on TLR-2 demonstrated that the resistance to cisplatin-induced cell death and apoptosis in OSCC cells were significantly higher in HSC3-M3 cells, a highly metastatic cell line, compared to HSC3 cells . This finding indicated that OSCC cells had an increased sensitivity to TLR2 as a result of becoming malignant.Thus, TLR-2 may play an important role in OSCC progression and probably participates in the limited curative effect of chemotherapy. However, the study lacked experiments showing that oral pathogens triggered TLR-2 activation. Therefore, the exact relationship has not been established and more studies should be conducted on TLR-2.

In contrast, another oral common bacterium,

Lactobacillus plantarum

, was found to induce apoptosis in oral cancer KB cells via the upregulation of PTEN and the downregulation of MAPK signaling pathways

[85]

.

Figure 2.

Mechanisms for how oral bacteria influence cell apoptosis.

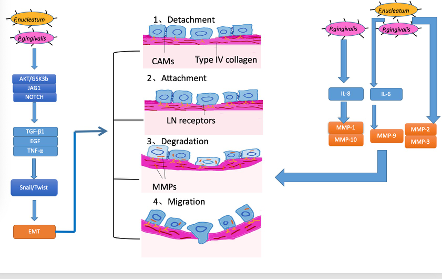

3.3. Invasion and Metastasis

The mechanisms of invasion and metastasis are related to cell adhesion molecules (CAM), the extracellular matrix (ECM), and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). EMT is the process whereby epithelial cells acquire mesenchymal features and has been most studied in the processes of inflammation, invasion, and metastasis in OSCC . For tumors, invasiveness and metastasis can be divided into four steps: separation from each other, increasing attachment with the basement membrane, the degradation of the extracellular matrix, and migration. According to several studies, EMT is linked to all four of these steps

( Figure 3).

Currently, periodontal bacteria were mostly studied (Figure 3). In vitro, heat-killed

P. gingivalis

or

F. nucleatum

triggered EMT-signaling pathways in OSCC cell line cultures (H400), which induced proinflammatory factors TGF-β1, EGF, and TNF-α. In this process, proinflammation cytokines TGF-β1, EGF, and TNF-α participated in a common EMT-signaling pathway, inducing the stabilization and activation of Snail. Snail and Twist are transcription factors that regulate the expression of tumor suppressors and are well-characterized regulators of E-cadherin expression

. In the former study, with the activation of Snail, E-cadherin expression decreased, which helped the cancer cells separate and attain the ability to invade and metastasize. Apart from EMT, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), involved in the breakdown of the basement membrane and facilitation of tumor metastasis, also plays an important role in invasiveness and metastasis in OSCC, and the production of MMP along with the activation of EMT was observed in certain studies . When MMPs emerge, they can dissolve the extracellular matrix and damage the basement membrane so that cancer cells can easily invade and transfer to distal locations

[91]

. Research on

P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum

reported the upregulation of MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9. Furthermore, other researchers demonstrated that oral pathogens triggered TLR signaling, causing IL-6 production that activated STAT3, which induced important effectors such as cyclinD1, MMP-9, and heparinase, driving OSCC growth and invasiveness. Moreover, Ha et al. infected OSCC cells with

P. gingivalis

twice a week for five weeks and found that

P. gingivalis

could stimulate MMP-1 and MMP-10 by releasing IL-8 and gingipain and increased the invasiveness of cancer cells

[92]

.

Figure 3.

Mechanisms for how oral bacteria promote invasion and metastasis.

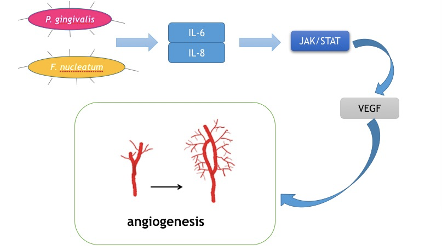

3.4. Promoting Angiogenesis

Cancer cells are capable of fast proliferation and invasion. In a word, cancer cells are always in a hyper-metabolic state. Therefore, angiogenesis is of vital importance in cancer development. Tongue cancer is of the most common oral cancer worldwide due to the rich blood supply in tongues . Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is the key mediator of angiogenesis. It stimulates irregular blood veins around cancer cells to provide nutrition and oxygen . Moreover, its involvement in the differentiation and prognosis of oral cancer has been reported. Recently, IL-6 was reported to induce VEGF production in OSCC. Mirkeshavarz et al. designed an experiment aimed at identifying the relationship between IL-6, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and VEGF production

. They cultured CAFs and oral cancer cells (OCCs) isolated from a 60-year-old male patient diagnosed with oral carcinoma separately and collectively and detected the production of IL-6 and VEGF. Their results showed that IL-6 was a factor that caused VEGF secretion in the CAF cell line and induced VEGF production in both the CAFs and OCCs. Combined with other studies, oral bacteria such as

P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum

could induce the production of IL-6.

et al. also found that the JAK/STAT signaling pathway participated in angiogenesis and could be activated by IL-6

[97]

. IL-8 has also been reported to activate the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, which may indicate another role in OSCC progression . Thus, it may be a feasible way for

P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum

to facilitate the development of OSCC, and by decreasing IL-6 and IL-8, the growth and invasion of cancer cells could be inhibited (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mechanism for how oral bacteria stimulate angiogenesis.

3.5. Assisting Cancer Stem Cells

It is well-known that OSCC patients have a low survival rate. This has been attributed to the enhanced tumorigenesis, increased invasiveness, and resistance to radiation and chemotherapy of cancer stem cells (CSC)

. CSCs are characterized by CD44, a type of membrane integrin

[102]

. Research conducted on oral bacteria in CSC is still lacking. However, several proinflammatory cytokines have been linked to CSCs, and oral bacteria might have an impact on CSCs as well. Patel et al. reported that cytokines in the tumor microenvironment had the ability to modulate CSC signaling pathways

[103]

. They reported that the increased levels of IL-6 and IL-8 in CSC samples were strongly associated with CD44, which could imply that the increased production of IL-6 and IL-8 by oral bacteria may present a favorable proinflammatory path for CSCs. A study conducted on CSCs derived from OSCC cell lines SAS and OECM-1 as well as a normal human gingival epithelioid cell line aimed to explore the cytotoxic effect of immune-modulatory proteins on OCSCs reported a tumor-suppressive effect via inhibition of the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway. Coincidentally, the IL-6/STAT3 pathway was also involved in the process by which

P. gingivalis

and

F. nucleatum

promoted the proliferation of cancer cells. Thus,

P. gingivalis

and

F. nucleatum

may stimulate the IL-6/STAT3 pathway and assist CSCs.

3.6. Evading Immune Attack

The immune system is an essential regulator of tumor biology with the capacity to inhibit tumor development, growth, invasion, and metastasis. However, various mechanisms of tumor escape from immune attack that make it hard to eliminate tumors have been discovered by scientists

.

In the past few years, the potential role of oral bacteria in this process has been elucidated. Our team evaluated the effect of

P. gingivalis

on the phagocytosis of Cal-27 cells (an OSCC cell line) by bone marrow-derived macrophages I and studied the effect of

P. gingivalis

on the growth of OSCC in vivo

[106]

.

P. gingivalis

was able to inhibit the phagocytosis of oral cancer cells by macrophages, and membrane-component molecules of

P. gingivalis

such as proteins were speculated to be the effector components. Meanwhile, sustained infection with antibiotic-inactivated

P. gingivalis

promoted OSCC growth in mice and induced the polarization of macrophages into M2 tumor-associated macrophages, which mainly displayed pro-tumor properties. These results all indicated that

P. gingivalis

could promote the immuno-evasion of oral cancer by protecting cancer cells from macrophage attack. A previous study using the squamous cell carcinoma cell line SCC-25 also verified that

P. gingivalis

could activate (B7-H1) receptors, which led to anergy and the apoptosis of activated T cells and helped cancer cells evade immune attack . These experiments provide another possible mechanism for how certain bacteria promote OSCC and suggest that reducing

P. gingivalis

might be a treatment direction.

References

- Warnakulasuriya, S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45,309–316.

- Seethala, R.R. Update from the 4th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumours: Preface. Head Neck Pathol. 2017, 11, 1–2.

- Ali, J.;Sabiha, B.;Jan, H.U.;Haider, S.A.;Khan, A.A.;Ali, S.S. Genetic etiology of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2017, 70, 23–28.

- Thomson, P.J.; Potten, C.S.; Appleton, D.R. Mapping dynamic epithelial cell proliferative activity within the oral cavity of man: A new insight into carcinogenesis? Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1999, 37, 377–383.

- Goodson, M.L.;Sloan, P.;Robinson, C.M.;Cocks, K.;Thomson, P.J. Oral precursor lesions and malignant transformation—Who, where, what, and when? Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 53, 831–835.

- Thomson, P.J. Potentially malignant disorders-The case for intervention. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2017, 46, 883–887.

- Omura, K. Current status of oral cancer treatment strategies: Surgical treatments for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 19, 423–430.

- Tampa, M.;Caruntu, C.;Mitran, M.;Mitran, C.;Sarbu, I.;Rusu, L.C.;Matei, C.;Constantin, C.;Neagu, M.;Georgescu, S.R. Markers of Oral Lichen Planus Malignant Transformation. Dis. Markers 2018, 2018, 1959506.

- Chen, I.H.;Chang, J.T.;Liao, C.T.;Wang, H.M.;Hsieh, L.L.;Cheng, A.J. Prognostic significance of EGFR and Her-2 in oral cavity cancer in betel quid prevalent area cancer prognosis. Br. J. Cancer 2003, 89, 681–686.

- Le Campion, A.;Ribeiro, C.M.B.;Luiz, R.R.;da Silva Júnior, F.F.;Barros, H.C.S.;Dos Santos, K.C.B.;Ferreira, S.J.;Gonçalves, L.S.;Ferreira, S.M.S. Low Survival Rates of Oral and Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Dent. 2017, 2017, 5815493.

- Suton, P.;Bolanca, A.;Grgurevic, L.;Erjavec, I.;Nikles, I.;Muller, D.;Manojlovic, S.;Vukicevic, S.;Petrovecki, M.;Dokuzovic, S., et al. Prognostic significance of bone morphogenetic protein 6 (BMP6) expression, clinical and pathological factors in clinically node-negative oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 80–86.

- Shrestha, A.D.;Vedsted, P.;Kallestrup, P.;Neupane, D. Prevalence and incidence of oral cancer in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 29, e13207.

- Jiang, S.; Dong, Y. Human papillomavirus and oral squamous cell carcinoma: A review of HPV-positive oral squamous cell carcinoma and possible strategies for future. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2017, 41, 323–327.

- Rupel, K.;Ottaviani, G.;Gobbo, M.;Poropat, A.;Zoi, V.;Zacchigna, S.;Di Lenarda, R.;Biasotto, M. Campaign to Increase Awareness of Oral Cancer Risk Factors Among Preadolescents. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 616–620.

- Macha, M.A.;Matta, A.;Kaur, J.;Chauhan, S.S.;Thakar, A.;Shukla, N.K.;Gupta, S.D.;Ralhan, R. Prognostic significance of nuclear pSTAT3 in oral cancer. Head Neck 2011, 33, 482–489.

- Peter, T. Managing oral potentially malignant disorders:A question of risk. J.F.d.j.2015, 6, 186–191.

- Lafuente Ibáñez de Mendoza, I.;Maritxalar Mendia, X.;García de la Fuente, A.M.;Quindós Andrés, G.;Aguirre Urizar, J.M. Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis in oral squamous cell carcinoma development: A systematic review. J. Periodontal Res. 2020, 55, 13–22.

- Yang, S.F.;Huang, H.D.;Fan, W.L.;Jong, Y.J.;Chen, M.K.;Huang, C.N.;Chuang, C.Y.;Kuo, Y.L.;Chung, W.H.;Su, S.C. Compositional and functional variations of oral microbiota associated with the mutational changes in oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2018, 77, 1–8.

- Zhang, W.L.;Wang, S.S.;Wang, H.F.;Tang, Y.J.;Tang, Y.L.;Liang, X.H.Who is who in oral cancer? Exp. Cell Res. 2019, 384, 111634.

- Kilian, M.;Chapple, I.L.;Hannig, M.;Marsh, P.D.;Meuric, V.;Pedersen, A.M.;Tonetti, M.S.;Wade, W.G.;Zaura, E.The oral microbiome—An update for oral healthcare professionals. Bdj 2016, 221, 657.

- Baker, J.L.;Bor, B.;Agnello, M.;Shi, W.;He, X. Ecology of the Oral Microbiome: Beyond Bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 362–374.

- Lee, W.H.;Chen, H.M.;Yang, S.F.;Liang, C.;Peng, C.Y.;Lin, F.M.;Tsai, L.L.;Wu, B.C.;Hsin, C.H.;Chuang, C.Y., et al. Bacterial alterations in salivary microbiota and their association in oral cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16540.

- Zhao, H.;Chu, M.;Huang, Z.;Yang, X.;Ran, S.;Hu, B.;Zhang, C.;Liang, J. Variations in oral microbiota associated with oral cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11773.

- Groeger, S.;Jarzina, F.;Domann, E.;Meyle, J. Porphyromonas gingivalis activates NFκB and MAPK pathways in human oral epithelial cells. BMC Immunol. 2017, 18, 1.

- Guerrero-Preston, R.;Godoy-Vitorino, F.;Jedlicka, A.;Rodríguez-Hilario, A.;González, H.;Bondy, J.;Lawson, F.;Folawiyo, O.;Michailidi, C.;Dziedzic, A., et al. 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing identifies microbiota associated with oral cancer, human papilloma virus infection and surgical treatment. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 51320–51334.

- Perera, M.;Al-Hebshi, N.N.;Perera, I.;Ipe, D.;Ulett, G.C.;Speicher, D.J.;Chen, T.;Johnson, N.W. Inflammatory Bacteriome and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 725–732.

- Al-Hebshi, N.N.;Nasher, A.T.;Maryoud, M.Y.;Homeida, H.E.;Chen, T.;Idris, A.M.;Johnson, N.W.. Inflammatory bacteriome featuring Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified in association with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1834.

- Yang, C.Y.;Yeh, Y.M.;Yu, H.Y.;Chin, C.Y.;Hsu, C.W.;Liu, H.;Huang, P.J.;Hu, S.N.;Liao, C.T.;Chang, K.P., et al.. Oral Microbiota Community Dynamics Associated With Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Staging. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 862.

- Schmidt, B.L.;Kuczynski, J.;Bhattacharya, A.;Huey, B.;Corby, P.M.;Queiroz, E.L.;Nightingale, K.;Kerr, A.R.;DeLacure, M.D.;Veeramachaneni, R., et al. Changes in abundance of oral microbiota associated with oral cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98741.

- Long, X.;Wong, C.C.;Tong, L.;Chu, E.S.H.;Ho Szeto, C.;Go, M.Y.Y.;Coker, O.O.;Chan, A.W.H.;Chan, F.K.L.;Sung, J.J.Y., et al. Peptostreptococcus anaerobius promotes colorectal carcinogenesis and modulates tumour immunity. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 2319–2330.

- Hansen, T.H.;Kern, T.;Bak, E.G.;Kashani, A.;Allin, K.H.;Nielsen, T.;Hansen, T.;Pedersen, O. Impact of a vegan diet on the human salivary microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5847.

- Wang, K.;Huang, Y.;Zhang, Z.;Liao, J.;Ding, Y.;Fang, X.;Liu, L.;Luo, J.;Kong, J. A Preliminary Study of Microbiota Diversity in Saliva and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid from Patients with Primary Bronchogenic Carcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 2819–2834.

- Yan, X.;Yang, M.;Liu, J.;Gao, R.;Hu, J.;Li, J.;Zhang, L.;Shi, Y.;Guo, H.;Cheng, J., et al. Discovery and validation of potential bacterial biomarkers for lung cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 5, 3111–3122.

- Gellatly, S.L.; Hancock, R.E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: New insights into pathogenesis and host defenses. Pathog. Dis. 2013, 67, 159–173.

- Elsen, S.;Collin-Faure, V.;Gidrol, X.;Lemercier, C. The opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa activates the DNA double-strand break signaling and repair pathway in infected cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 4385–4397.

- Nobbs, A.H.; Jenkinson, H.F.; Jakubovics, N.S. Stick to your gums: Mechanisms of oral microbial adherence. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 1271–1278.

- Zhang, G.; Chen, R.; Rudney, J.D. Streptococcus cristatus modulates the Fusobacterium nucleatum-induced epithelial interleukin-8 response through the nuclear factor-kappa B pathway. J. Periodontal. Res. 2011, 46, 558–567.

- Takahashi, Y.;Park, J.;Hosomi, K.;Yamada, T.;Kobayashi, A.;Yamaguchi, Y.;Iketani, S.;Kunisawa, J.;Mizuguchi, K.;Maeda, N., et al. Analysis of oral microbiota in Japanese oral cancer patients using 16S rRNA sequencing. J. Oral Biosci. 2019, 61, 120–128.

- Mok, S.F.;Karuthan, C.;Cheah, Y.K.;Ngeow, W.C.;Rosnah, Z.;Yap, S.F.;Ong, H.K.A. The oral microbiome community variations associated with normal, potentially malignant disorders and malignant lesions of the oral cavity. Malays. J. Pathol. 2017, 39, 1–15.

- Tjalsma, H.;Boleij, A.;Marchesi, J.R.;Dutilh, B.E. A bacterial driver-passenger model for colorectal cancer: Beyond the usual suspects. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 575–582.

- Geng, J.;Song, Q.;Tang, X.;Liang, X.;Fan, H.;Peng, H.;Guo, Q.;Zhang, Z.. Co-occurrence of driver and passenger bacteria in human colorectal cancer. Gut Pathog. 2014, 6, 26.

- Ikebe, M.;Kitaura, Y.;Nakamura, M.;Tanaka, H.;Yamasaki, A.;Nagai, S.;Wada, J.;Yanai, K.;Koga, K.;Sato, N., et al.. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) increases the invasive ability of pancreatic cancer cells through the TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway. J. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 100, 725–731.

- Kuboniwa, M.;Hasegawa, Y.;Mao, S.;Shizukuishi, S.;Amano, A.;Lamont, R.J.;Yilmaz, O. Gingivalis accelerates gingival epithelial cell progression through the cell cycle. Microbes Infect. 2008, 10, 122–128.

- Bronzato, J.D.;Bomfim, R.A.;Edwards, D.H.;Crouch, D.;Hector, M.P.;Gomes, B. Detection of Fusobacterium in oral and head and neck cancer samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Oral Biol. 2020, 112, 104669.

- Punyani, S.R.; Sathawane, R.S. Salivary level of interleukin-8 in oral precancer and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Oral Investig. 2013, 17, 517–524.

- Abdulkareem, A.A.;Shelton, R.M.;Landini, G.;Cooper, P.R.;Milward, M.R. Periodontal pathogens promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition in oral squamous carcinoma cells in vitro. Cell Adh. Migr. 2018, 12, 127–137.

- Binder Gallimidi, A.;Fischman, S.;Revach, B.;Bulvik, R.;Maliutina, A.;Rubinstein, A.M.;Nussbaum, G.;Elkin, M. Periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum promote tumor progression in an oral-specific chemical carcinogenesis model. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 22613–22623.

- Zhang, L.;Liu, Y.;Zheng, H.J.;Zhang, C.P. The Oral Microbiota May Have Influence on Oral Cancer. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 476.

- Saxena, D.;Pushalkar, S.;Devotta, A.;Li, Y.;Singh, B.;Kurago, Z.K.;Kerr, A.;Yan, W.;Sacks, P.;Li, X. Abstract 4834: Microbiome in Oral Epithelial Dysplasia and Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 4834–4834.

- Su, Z.;Yang, Z.;Xu, Y.;Chen, Y.;Yu, Q. Apoptosis, autophagy, necroptosis, and cancer metastasis. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 48.

- Jou, A.; Hess, J. Epidemiology and Molecular Biology of Head and Neck Cancer. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2017, 40, 328–332.

- Marur, S.; Forastiere, A.A. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Update on Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 386–396.

- Wu, T.; Dai, Y. Tumor microenvironment and therapeutic response. Cancer Lett. 2017, 387, 61–68.

- Yang, L.; Lin, P.C. Mechanisms that drive inflammatory tumor microenvironment, tumor heterogeneity, and metastatic progression. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2017, 47, 185–195.

- Rivera, C. Essentials of oral cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 11884–11894.

- Multhoff, G.; Molls, M.; Radons, J. Chronic inflammation in cancer development. Front. Immunol. 2011, 2, 98.

- Francescone, R.; Hou, V.; Grivennikov, S.I. Microbiome, inflammation, and cancer. Cancer J. 2014, 20, 181–189.

- Hoppe, T.;Kraus, D.;Novak, N.;Probstmeier, R.;Frentzen, M.;Wenghoefer, M.;Jepsen, S.;Winter, J.Oral pathogens change proliferation properties of oral tumor cells by affecting gene expression of human defensins. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 13789–13798.

- Bloom, J.; Cross, F.R. Multiple levels of cyclin specificity in cell-cycle control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 149–160.

- Knippschild, U.;Milne, D.M.;Campbell, L.E.;DeMaggio, A.J.;Christenson, E.;Hoekstra, M.F.;Meek, D.W. p53 is phosphorylated in vitro and in vivo by the delta and epsilon isoforms of casein kinase 1 and enhances the level of casein kinase 1 delta in response to topoisomerase-directed drugs. Oncogene 1997, 15, 1727–1736.

- Vousden, K.H. Outcomes of p53 activation—Spoilt for choice. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 5015–5020.

- Kim, D.;Dan, H.C.;Park, S.;Yang, L.;Liu, Q.;Kaneko, S.;Ning, J.;He, L.;Yang, H.;Sun, M., et al. AKT/PKB signaling mechanisms in cancer and chemoresistance. Front. Biosci. 2005, 10, 975–987.

- García, Z.;Kumar, A.;Marqués, M.;Cortés, I.;Carrera, A.C. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase controls early and late events in mammalian cell division. Embo J. 2006, 25, 655–661.

- Ramos-García, P.;Gil-Montoya, J.A.;Scully, C.;Ayén, A.;González-Ruiz, L.;Navarro-Triviño, F.J.;González-Moles, M.A. An update on the implications of cyclin D1 in oral carcinogenesis. Oral Dis. 2017, 23, 897–912.

- Wang, Y.;Liu, S.;Li, B.;Jiang, Y.;Zhou, X.;Chen, J.;Li, M.;Ren, B.;Peng, X.;Zhou, X., et al. Staphylococcus aureus induces COX-2-dependent proliferation and malignant transformation in oral keratinocytes. J. Oral Microbiol. 2019, 11, 1643205.

- Wang, Y.;Ren, B.;Zhou, X.;Liu, S.;Zhou, Y.;Li, B.;Jiang, Y.;Li, M.;Feng, M.;Cheng, L. Growth and adherence of Staphylococcus aureus were enhanced through the PGE2 produced by the activated COX-2/PGE2 pathway of infected oral epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177166.

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516.

- Cao, K.; Tait, S.W.G. Apoptosis and Cancer: Force Awakens, Phantom Menace, or Both? Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 337, 135–152.

- Yao, L.;Jermanus, C.;Barbetta, B.;Choi, C.;Verbeke, P.;Ojcius, D.M.;Yilmaz, O. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection sequesters pro-apoptotic Bad through Akt in primary gingival epithelial cells. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2010, 25, 89–101.

- Yilmaz, O.;Jungas, T.;Verbeke, P.;Ojcius, D.M. Activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway contributes to survival of primary epithelial cells infected with the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 3743–3751.

- Singh, M.K.; Sharma, B.; Tiwari, P.K. The small heat shock protein Hsp27: Present understanding and future prospects. J. Therm Biol. 2017, 69, 149–154.

- Lee, J.;Roberts, J.S.;Atanasova, K.R.;Chowdhury, N.;Yilmaz, Ö. A novel kinase function of a nucleoside-diphosphate-kinase homologue in Porphyromonas gingivalis is critical in subversion of host cell apoptosis by targeting heat-shock protein 27. Cell Microbiol. 2018, 20, e12825.

- Mao, S.;Park, Y.;Hasegawa, Y.;Tribble, G.D.;James, C.E.;Handfield, M.;Stavropoulos, M.F.;Yilmaz, O.;Lamont, R.J.Intrinsic apoptotic pathways of gingival epithelial cells modulated by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Cell Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1997–2007.

- Groeger, S.;Domann, E.;Gonzales, J.R.;Chakraborty, T.;Meyle, J. B7-H1 and B7-DC receptors of oral squamous carcinoma cells are upregulated by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Immunobiology 2011, 216, 1302–1310.

- Kotrashetti, V.S.;Nayak, R.;Bhat, K.;Hosmani, J.;Somannavar, P. Immunohistochemical expression of TLR4 and TLR9 in various grades of oral epithelial dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma, and their roles in tumor progression: A pilot study. Biotech. Histochem. 2013, 88, 311–322.

- Zeljic, K.;Supic, G.;Jovic, N.;Kozomara, R.;Brankovic-Magic, M.;Obrenovic, M.;Magic, Z. Association of TLR2, TLR3, TLR4 and CD14 genes polymorphisms with oral cancer risk and survival. Oral Dis. 2014, 20, 416–424.

- Omar, A.A.;Korvala, J.;Haglund, C.;Virolainen, S.;Häyry, V.;Atula, T.;Kontio, R.;Rihtniemi, J.;Pihakari, A.;Sorsa, T., et al. Toll-like receptors -4 and -5 in oral and cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2015, 44, 258–265.

- Mäkinen, L.K.;Ahmed, A.;Hagström, J.;Lehtonen, S.;Mäkitie, A.A.;Salo, T.;Haglund, C.;Atula, T. Toll-like receptors 2, 4, and 9 in primary, metastasized, and recurrent oral tongue squamous cell carcinomas. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2016, 45, 338–345.

- Cen, X.; Liu, S.; Cheng, K. The Role of Toll-Like Receptor in Inflammation and Tumor Immunity. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 878.

- Liu, C.; Han, C.; Liu, J. The Role of Toll-Like Receptors in Oncotherapy. Oncol. Res. 2019, 27, 965–978.

- Ikehata, N.;Takanashi, M.;Satomi, T.;Watanabe, M.;Hasegawa, O.;Kono, M.;Enomoto, A.;Chikazu, D.;Kuroda, M. Toll-like receptor 2 activation implicated in oral squamous cell carcinoma development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 2227–2234.

- Hofmann, K.; Bucher, P.; Tschopp, J. The CARD domain: A new apoptotic signalling motif. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997, 22, 155–156.

- Hartner, L. Chemotherapy for Oral Cancer. Dent. Clin. North Am. 2018, 62, 87–97.

- Sun, Z.;Luo, Q.;Ye, D.;Chen, W.;Chen, F. Role of toll-like receptor 4 on the immune escape of human oral squamous cell carcinoma and resistance of cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Mol. Cancer 2012, 11, 33.

- Asoudeh-Fard, A.;Barzegari, A.;Dehnad, A.;Bastani, S.;Golchin, A.;Omidi, Y. Lactobacillus plantarum induces apoptosis in oral cancer KB cells through upregulation of PTEN and downregulation of MAPK signalling pathways. Bioimpacts 2017, 7, 193–198.

- Pastushenko, I.; Blanpain, C. EMT Transition States during Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 212–226.

- Zeisberg, M.; Neilson, E.G. Biomarkers for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J. Clin. Invest. 2009, 119, 1429–1437.

- Mittal, V. Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition in Tumor Metastasis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2018, 13, 395–412.

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, B.P. Snail: More than EMT. Cell Adh. Migr. 2010, 4, 199–203.

- Lo, H.W.;Hsu, S.C.;Xia, W.;Cao, X.;Shih, J.Y.;Wei, Y.;Abbruzzese, J.L.;Hortobagyi, G.N.;Hung, M.C. Epidermal growth factor receptor cooperates with signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 to induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer cells via up-regulation of TWIST gene expression. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 9066–9076.

- Cui, N.; Hu, M.; Khalil, R.A. Biochemical and Biological Attributes of Matrix Metalloproteinases. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2017, 147, 1–73.

- Ha, N.H.;Woo, B.H.;Kim, D.J.;Ha, E.S.;Choi, J.I.;Kim, S.J.;Park, B.S.;Lee, J.H.;Park, H.R. Prolonged and repetitive exposure to Porphyromonas gingivalis increases aggressiveness of oral cancer cells by promoting acquisition of cancer stem cell properties. Tumour. Biol. 2015, 36, 9947–9960.

- Ghantous, Y.; Elnaaj, I.A. Global incidence and risk factors of oral cancer. Harefuah 2017, 156, 645–649.

- Carmeliet, P. VEGF as a key mediator of angiogenesis in cancer. Oncology 2005, 69 (Suppl. 3), 4–10.

- Patel, K.R.;Vajaria, B.N.;Begum, R.;Patel, J.B.;Shah, F.D.;Joshi, G.M.;Patel, P.S. VEGFA isoforms play a vital role in oral cancer progression. Tumour. Biol. 2015, 36, 6321–6332.

- Mirkeshavarz, M.;Ganjibakhsh, M.;Aminishakib, P.;Farzaneh, P.;Mahdavi, N.;Vakhshiteh, F.;Karimi, A.;Gohari, N.S.;Kamali, F.;Kharazifard, M.J., et al. Interleukin-6 secreted by oral cancer- associated fibroblast accelerated VEGF expression in tumor and stroma cells. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017, 63, 131–136.

- Huang, J.S.;Yao, C.J.;Chuang, S.E.;Yeh, C.T.;Lee, L.M.;Chen, R.M.;Chao, W.J.;Whang-Peng, J.;Lai, G.M. Honokiol inhibits sphere formation and xenograft growth of oral cancer side population cells accompanied with JAK/STAT signaling pathway suppression and apoptosis induction. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 245.

- González-Moles, M.A.;Scully, C.;Ruiz-Ávila, I.;Plaza-Campillo, J.J. The cancer stem cell hypothesis applied to oral carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2013, 49, 738–746.

- Bhutia, S.K.;Naik, P.P.;Praharaj, P.P.;Panigrahi, D.P.;Bhol, C.S.;Mahapatra, K.K.;Saha, S.;Patra, S.. Identification and Characterization of Stem Cells in Oral Cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2002, 129–139.

- Wang, T.Y.;Yu, C.C.;Hsieh, P.L.;Liao, Y.W.;Yu, C.H.;Chou, M.Y. GMI ablates cancer stemness and cisplatin resistance in oral carcinomas stem cells through IL-6/Stat3 signaling inhibition. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 70422–70430.

- Gemenetzidis, E.;Gammon, L.;Biddle, A.;Emich, H.;Mackenzie, I.C. Invasive oral cancer stem cells display resistance to ionising radiation. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 43964–43977.

- Oliveira, L.R.;Oliveira-Costa, J.P.;Araujo, I.M.;Soave, D.F.;Zanetti, J.S.;Soares, F.A.;Zucoloto, S.;Ribeiro-Silva, A. Cancer stem cell immunophenotypes in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2011, 40, 135–142.

- Patel, S.; Rawal, R.J.T.B. Role of miRNA dynamics and cytokine profile in governing CD44v6/Nanog/PTEN axis in oral cancer: Modulating the master regulators. Tumour Biol, 2016, 37, 14565–14575.

- Beatty, G.L.; Gladney, W.L. Immune escape mechanisms as a guide for cancer immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res 2015, 21, 687–692.

- Friedrich, M.;Jasinski-Bergner, S.;Lazaridou, M.F.;Subbarayan, K.;Massa, C.;Tretbar, S.;Mueller, A.;Handke, D.;Biehl, K.;Bukur, J., et al. Tumor-induced escape mechanisms and their association with resistance to checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2019, 68, 1689–1700.

- Liu, S.;Zhou, X.;Peng, X.;Li, M.;Ren, B.;Cheng, G.;Cheng, L. Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes Immunoevasion of Oral Cancer by Protecting Cancer from Macrophage Attack. J. Immunol. 2020, 205, 282–289.