Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Wai Yin Wong and Version 1 by Abdul Hanan.

Green hydrogen production via electrocatalytic water splitting paves the way for renewable, clean, and sustainable hydrogen (H2) generation. H2 gas is produced from the cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), where the reaction is catalyzed primarily from Pt-based catalysts under both acidic and alkaline environments. MXene is a 2D nanomaterial based on transition-metal carbide or nitride, having the general formula of Mn+1XnTx, where M = transition metal, X = C and/or N and Tx = surface termination groups such as F, O, OH and Cl.

- hydrogen

- hydrogen evolution reaction

- nanomaterials

- MXenes

- Electrocatalysts

1. Introduction

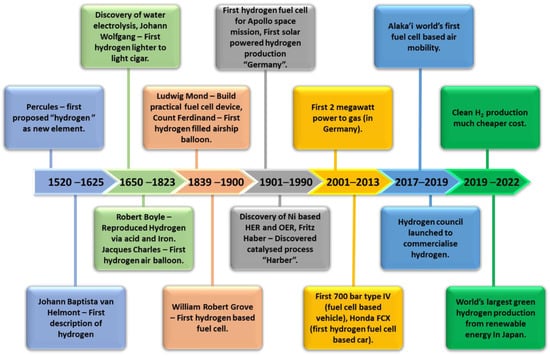

Hydrogen (H2) as a fuel offers the pathway for a clean, abundant, renewable and efficient source of energy that is currently crucial in the worldwide effort to lower emissions of harmful pollutants. The implementation of H2 in fuel cells came about around 219 years after its discovery, as can be seen in the timeline in Figure 1. The technology has evolved from its first use in the U.S. Apollo Space Program in the 1950s to the development of the first fuel-cell vehicle in the 2000s [1]. Throughout this course, the utilization of H2 as fuels further developed for their production using renewable energy approaches since the implementation of the world’s first solar-powered H2 production towards the development of the grid system for hydrogen generation in the 2020s and onwards. Hydrogen is an abundant element and non-toxic. Utilizing H2 in hydrogen fuel-cell systems is able to generate electricity with only water and heat as by-products [2,3]. However, the majority (95%) of global hydrogen production is still based on non-renewable resources via steam methane reforming, as of 2020, emitting 830 tonnes of CO2 annually [4,5]. Therefore, sustainable hydrogen generation should be sourced from renewable sources while reducing CO2 emissions. Green hydrogen adopts H2 production methods that do not rely on non-renewable sources such as fossil fuels. Water electrolysers are an emerging technology that utilizes photocatalytic or electrocatalytic water splitting to generate H2 [6,7,8]. Integrating electrolysers with renewable sources such as solar and wind power provides us with green and environmentally friendly H2 sources with no toxic by-products. An alkaline water electrolyser is a developed technology that generates H2 by water electrolysis. However, highly concentrated potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution in alkaline electrolysers poses a great risk of component corrosion [9]. The proton exchange membrane water electrolyser (PEMWE) and anion exchange membrane water electrolyser (AEMWE) offer a more compact design that uses a lower-concentration electrolyte (0.5 M sulfuric acids (H2SO4) for PEMWE and 1 M KOH for AEMWE) and is able to overcome some limitations related to corrosion and carbonate formation in conventional electrolysers [9,10,11,12,13].

Figure 1. Timeline on the development of H2 utilization as fuel.

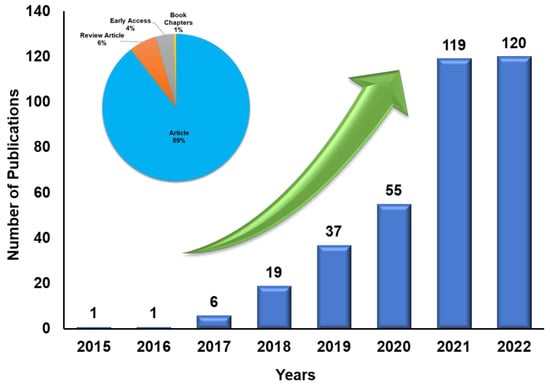

The electrochemical water-splitting system has two essential reactions: hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER). The ideal thermodynamic potential to split water into its component hydrogen and oxygen is 1.23 V. In practice, the potential is much higher due to the mass, electrolyte and transport resistances, in addition to the slow HER and OER kinetics. Additional potential to achieve water splitting is known as overpotential [14]. HER is the cathode reaction in the water electrolyser where H2 is generated. Active research is still ongoing in the field of HER. Moreover, increasing publications related to HER show that challenges and opportunities still exist to be tackled (Figure 2). The rate at which HER occurs varies between the acidic and alkaline electrolyte environments [15,16]. The H2 production rate is determined from the activity of the HER electrocatalyst, where it is desired to have a high current density at the lowest possible potential. Therefore, the smaller HER overpotential of an electrocatalyst indicates its high activity. The benchmark HER electrocatalysts are based on noble or platinum-group metals (PGM), most commonly Pt/C, owing to their very low overpotential in acidic and alkaline conditions [17]. Therefore, to lower the cost of electrode fabrication, PGM-based catalyst loading must be minimized without losing the optimum HER activity.

Figure 2. Various research publications during the last ten years toward HER (keywords: HER, MXenes). Source: Web of Science, https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/summary/aa561b6b-209c-40c7-9557-00595d867918-62e97e6f/relevance/1, accessed on 14 November 2022.

Various electrocatalysts alternative to Pt/C has been extensively studied to identify the best lower-cost catalysts for HER [18]. Ni, Mo and Co-based materials are among the potential catalysts for HER. This includes alloys such as NiMo, transition-metal sulphides, chalcogenides and nitrides [19]. Single-atom catalysts (SACs) such as those of Pt and Ir SACs offer the advantage of utilizing ultra-low loadings of PGM-based catalysts [20]. However, nanoparticles/nanosheets of these catalysts, including SACs, are prone to aggregation, causing instability in their HER performance. Two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials such as graphene and MXene are excellent supports to stabilize these catalysts, which in turn also enhances the HER. MXenes, belonging to a family of 2D transition metal carbides/nitrides, contain an abundance of the termination groups on their basal planes that enable them to anchor catalyst nanoparticles and SACs, facilitating the catalysts’ distribution [20,21,22,23]. These termination groups (–O, –F and –OH) also participate in HER as active sites. Their high conductivity helps lower the electron transfer resistance for enhancing intrinsic HER activity. The types of transition metal and whether it is carbide or nitride determine the electronic structure of MXene and its effectiveness towards HER alongside the termination groups [21]. Past reviews have highlighted the properties of different types of MXenes, the effect of termination groups, their synthesis and their roles as supports for catalysts for HER as well as other applications, including OER [21], photocatalytic water splitting [24], CO2 reduction [24,25] and nitrogen reduction reaction [26]. While the MXene types and their atomic structure significantly affect catalytic activity, the Mxene’s morphology also contributes to the catalysts. Since its discovery in 2011, MXenes with different structures and morphologies, such as multilayer, few-layer and porous, have been successfully synthesized and investigated. Changing morphologies can determine how well the MXene participates in the HER by the ease of access to its active sites, its resistance to restacking, overall surface area, effectiveness in supporting HER-active phases and its durability. Hence, identifying the most suitable out of all the possible MXene morphologies can help cater to the improvement of the overall HER performance.

2. Hydrogen Evolution Reaction

HER occurs as a cathode reaction within the water electrolyser system, where water is reduced to generate H2 (2H+ + 2e− → H2) [27]. It is a two-electron transfer system with one catalytic step in general [28,29,30]. Therefore, to achieve high kinetic effectiveness for electrochemical water splitting, an active electrocatalyst must be used to reduce the overpotential that drives the HER process [31]. The PGM-based electrocatalyst platinum (Pt) is a well-known HER catalyst that needs smaller overpotentials even at high reaction rates (especially in acidic solutions). Pt/C can typically exhibit overpotentials as low as 20 mV to around 80 mV at 10 mA/cm2 [32,33]. However, the scarcity and high cost of Pt limit its technological usage, prompting the effort to minimize the loading of Pt in electrodes or replace it with lower-cost transition-metal-based electrocatalysts.2.1. Mechanism of Electrochemical HER

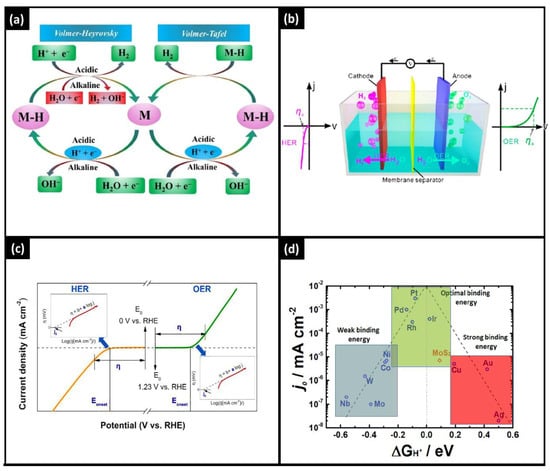

The mechanism of HER is dependent on the driving environment, such as alkaline and acidic solutions [34], represented by Equations (1) and (2), respectively. Further, the literature shows that these equations are furthermore divided into various sub-steps [35]. It contains proposed HER kinetics in acidic and alkaline environments, as depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. (a) The Volmer, Heyrovsky and Tafel reaction mechanisms of electrochemical water splitting. (b) Electrocatalysis chamber with anodic and cathodic approaches. (c) Overall, HER and OER kinetics. (d) Various electrocatalysts for HER through volcanic plot.

2.2. Catalyst Activity toward Overpotential, Current Density and Tafel Slope

Because of fundamental activity, hurdles found on both the anode and the cathode are really what primarily causes the excessive potential, also known as overpotential (η), to exist. Therefore, assessing electrocatalysts’ activity and overpotential is a significant feature. The overpotential value associated with a current density of 10 mA/cm2 is typically utilized to compare the activity of various catalysts [41,42,43]. The Tafel slope as well as exchange current, which are also additional parameters to assess activity through overpotential vs. reactive current connection, are expressed in the following equation: η = a + b log j, where j is the current density, and η is the overpotential (shown in Figure 3c). The linear connection refers to two notable kinetic parameters for the Tafel plot. The other is the exchange current density (j0), which may be determined by extracting the current at zero overpotential. One is the Tafel slope (b). According to the kinetics of electron transport, the Tafel slope (b) is associated with the catalytic reaction mechanism [44]. The lower Tafel slope indicates that the electrocatalytic reaction kinetics is occurring more quickly and that the overpotential shift results in a significant increase in current density [45]. Under equilibrium conditions, overall basic electron transfer is described by the exchange current density [46]. Greater charge transfer rates and a lower response barrier are correlated with increased exchange current density.2.3. Catalyst Activity for Current–Time Curve

Stability is a key factor in determining if a catalyst has the potential to be used in experimental water-splitting cells [47]. There are two approaches to determining stability. One of those is by using chronoamperometry (I-t curve) and chronopotentiometry (E-t curve), which measure both occurrences with time under a constant potential or the potential variation with time under a fixed current [48]. The higher the stability of the catalyst, the faster the tested current or potential is the same. People frequently set a current density of greater than 10 mA/cm2 for at least 10 h of testing in order to compare results with those of other research groups [35]. Another method is cyclic voltammetry (CV), which determines current by cycling the potential and often requires more than 5000 cycles at a scan rate (such as 50 mV/s) [49]. The chronopotentiometric technique used linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) to investigate an overpotential change before and after the durability test. The electrocatalyst with the lowest potential change is considered to be the desirable electrocatalyst [50].2.4. Efficiency toward Turnover Frequency (TOF) and Faradaic Efficiency

Turnover frequency (TOF) is an important parameter for describing the kinetics rate of catalytic sites, which indicates significant activity of the metal catalysts [51]. In addition, the TOF generally shows how several reactants may be transformed into the required product per active site per unit of time [52]. Furthermore, calculating the total TOF value for more heterogeneous electrocatalysts for catalytic sites at every electrode is often an estimation [53]. Furthermore, while being an imperfect method, TOF is a crucial tool for comparing the catalytic activity of diverse catalysts, particularly within a comparable system or under similar conditions [54]. Its faradaic efficiency is a quantitative technique for defining the effectiveness of transferring electrons from an external circuit toward the surface of the electrode for such an electrochemical reaction [55]. The ratio of experimentally examined amount of H2 or O2 to theoretically determined mass of H2 or O2 is known as faradaic efficiency [56,57,58]. The theoretical values can be estimated using chronoamperometry or chronopotentiometric analysis. On the other hand, the experimental values can be obtained by measuring the gas generation using the water-gas displacement technique or gas chromatography [59]. The focus of research and development affects the study of electrocatalyst stability, activity and efficiency. Furthermore, in accordance with the specific concentration for efficiency, analysis, structural characterization and process determination, the current studies of reaction, efficiency and stability may be gathered in three areas for the synthesis and production of an electrocatalyst [60]. Assessment of the current/potential-time curve, on the other hand, provides information for assessing the stability of the electrocatalyst, which is helpful for practical applications [61]. Finally, estimating overpotential, Tafel slope, exchange current density, faradaic efficiency and turnover frequency are the primary parameters for assessing electrocatalytic kinetics [62]. Notably, coupling these electrochemical approaches to spectroscopic and microscopic levels provides the structural properties required to design a robust and active electrocatalyst.3. MXenes as Emerging Materials for HER

MXene is a 2D nanomaterial based on transition-metal carbide or nitride, having the general formula of Mn+1XnTx, where M = transition metal, X = C and/or N and Tx = surface termination groups such as F, O, OH and Cl. The n number varies from 1 to 4 [148,149,150]. MXene is fabricated from the etching of MAX phases, where their general formula is Mn+1AXn. ‘A’ is the group 13–16 elements (i.e., Al, Ga), where n varies from 1 to 3. During etching, the ‘A’ layer is removed as the metallic bonding of the M-A bonds is weaker than the ionic/covalently bonded M-X bonds [149,151]. MXene has been extensively studied for the application of electrocatalytic HER as well as OER for water splitting. Past reviews have highlighted the clear potential of different types of MXenes based on Ti, Mo and V. Table 2 summarizes the HER properties of several common MXenes studied for HER. Yet, the Ti-based MXenes, particularly the Ti3C2Tx or Ti3C2, showed the majority. Termination groups are crucial for MXene’s role in HER and as support. This is owing to their characteristics, including large surface area, metallic properties, high electron conductivity and the presence of hydrophilic termination groups [21]. Gibbs free energy for hydrogen adsorption (ΔGHads) and intrinsic HER activity highly depend on ‘M’ transition metal and the surface termination groups. For instance, Mo-based Mo2CTx MXenes are more catalytically active for HER than the most commonly used Ti-based MXenes [152]. O-termination groups also benefit HER. It has been shown that O-groups facilitate the desorption of H from the MXene surface, bringing the ΔGHads closer to optimum (zero). HER activity is limited if the F-termination coverage is high [153,154]. In terms of their durability, pristine MXenes such as Ti3C2Tx are prone to oxidation within a short term (~12 days) when exposed to oxygen in the water. Modifications such as doping will potentially minimize oxidation to extend the MXene’s durability [155].Table 2. Summary of HER properties of commonly used MXenes under different structures and conditions.

| MXene | Structure | Electrolyte | Overpotential (mV) @ 10 mA/cm2 | Tafel Slope (mV/dec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti3C2Tx [156,157] | Multilayer | 1 M KOH | >600 | - |

| Ti3C2Tx [158] | Few layer | 1 M KOH | >500 | >100 |

| Ti3C2Tx [152] | Few-layer | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 609 | 124 |

| Ti3C2Ox [159] | Few-layer | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 190 | 60.7 |

| Ti3C2(OH)x [159] | Few-layer | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 217 | 88.5 |

| Mo2CTx [152] | Few-layer | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 283 | 82 |

| Mo2CTx [160] | Few-layer | 1 M KOH | 300 | 110 |

| Mo2CTx [161] | Multilayer | 1 M KOH | 280 | 118 |

The electronic structure of MXene plays a role in the intrinsic activity toward HER. Electronic properties are affected by a number of factors, including the ‘M’ element, surface terminations, layer thickness, effects of intercalation, and adding dopants. Pristine M2X MXenes are primarily metallic. The presence of termination groups on the basal planes results in additional energy bands below the Fermi level that shift the MXene into a semiconductor, such as those of Ti2CO2. Ti3C2Tx can exhibit metallic properties where it was found that F-groups occupy the face-centred cubic adsorption site while O-groups have a partial occupation on the bridge sites and hexagonal close-packed sites [162]. Further, electronic properties may vary between multilayer and few-layer Ti3C2Tx given that few-layers may offer a larger in-plane conductivity [163,164]. Ti- and V-based MXenes also offer very high electron conductivity exceeding 1000 S/cm [165]. High electron conductivity is desired for active HER . The electronic properties are adjusted by doping the MXene and introducing the HER-active materials. MXene also affects the electronic properties of the interacting material. Kong et al. [166] found that the Ti site favours H adsorption in Ti3C2O2 quantum dots (QDs). Graphene is able to form an interfacial interaction with the Ti3C2O2 QDs that stabilizes the C—O configuration and shifts the d-band centre energy level by 0.4–0.5 eV in the Ti3C2O2. The graphene-Ti3C2O2 QDs with Gibbs free energy closer to zero value are more favourable towards HER. On the other hand, Ren et al. [167] reported that H-adsorption occurs on the O-sites within the hybrid of MoS2@Mo2CO2. The catalyst also exhibits metallic properties and Gibbs free energy for hydrogen adsorption ΔGHads closer to optimal. Interaction between the MoS2 and the Mo2CO2 is also interfacial through charge transfer. The exchange of electrons between the two components is one of the drivers of improved HER. Single-atom catalysts (SACs) and doping on MXene have positive outcomes for HER. In the case of Ru SACs on Ti3C2Tx with N-doping, Ti—N and N—Ti—O bonds are formed after N-doping on the Ti3C2Tx. Ru SACs are attached in the form of pyrollic-N—Ru bonds. Interactions between MXene, Ru SACs and the N-groups result in a greater total density of state (TDOS) value indicating better electron conductivity. The partial density of state (PDOS) of RuSA-N-Ti3C2Tx near the Fermi level is attributed to the d-orbitals of Ti and Ru, where the Ru SACs brought about d-electron domination near the Fermi level that in turn benefits HER [168]. For transition-metal SACs, Co SACs in V2CTx MXenes showed that electron transfer occurred between the Co SACs and V2CTx through —O— bonds that facilitate early-stage water dissociation. The d-band centre of Co@V2CTx is brought to an intermediate level and has high electron cloud distribution. d-band centre that is nearer the Fermi level is more favourable for adsorption/desorption of intermediates for both HER and OER [169]. Therefore, the electronic structure of MXene would tailor the electron conductivity and intrinsic activity towards HER. Dopants and introducing HER-active materials potentially result in electron redistribution that may lead to more favourable HER binding energies.

Another factor is that the morphology of MXenes can be tailored into several different morphological structures. For example, Multilayer MXenes are intercalated and then delaminated to form nanosheets of few-layer MXenes. Further modifications can produce structures with multiple pores [170] and unique structures such as crumpled [171], rolled [110], and spheres [172]. Various morphology changes the overall surface area of MXene, the termination groups/active sites’ accessibility through the electrocatalytic active surface area (ECSA), electron conductivity, its ability to anchor the HER-active materials (Ni-based HER catalysts, single-atom catalysts, etc.) and their durability. This affects the overall HER activity of the MXene and MXene composites/hybrid catalysts. Several of these different morphologies of MXenes have been studied for HER.