Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Cyriac Abby Philips and Version 2 by Dean Liu.

TIPS involves creating an artificial conduit between the hepatic and portal veins to decrease the portal pressure and resolve the associated complications of portal hypertension. The procedure has traditionally been performed under fluoroscopic guidance with or without wedge portography or carbon dioxide angiography to delineate the portal venous branches. In patients with anatomically challenging scenarios such as chronic portal vein thrombosis, traditional TIPS procedure methods may not prove technically successful.

- TIPS

- EHPVO

- anticoagulation

- transhepatic

1. Transjugular Approach

A standard transjugular approach with real-time transabdominal or intravascular ultrasound guidance remains one of the preferred approaches to TIPS in chronic PVT (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Simultaneous ultrasound guidance allows the operator to access the thrombosed native portal vein. Use of this route not only reduces the procedure time and associated risks of prolonged radiation exposure but avoids several other potentially life-threatening complications of TIPS such as capsular transgression and hemoperitoneum, inadvertent puncture of an artery or periportal collateral vessels, biliary injury, and access site complications (in cases of transhepatic or trans-splenic approach) [1][17]. The need for an extra set of expert hands for ultrasound guidance and unfavorable body habitus in some patients remains a drawback. Moreover, the thrombosed or fibrotic intrahepatic branch of the native portal vein should be visible on the ultrasound for this approach to work. The fluoroscopy-guided puncture of the non-visualized fibrotic portal vein from the transjugular approach has found limited technical success.

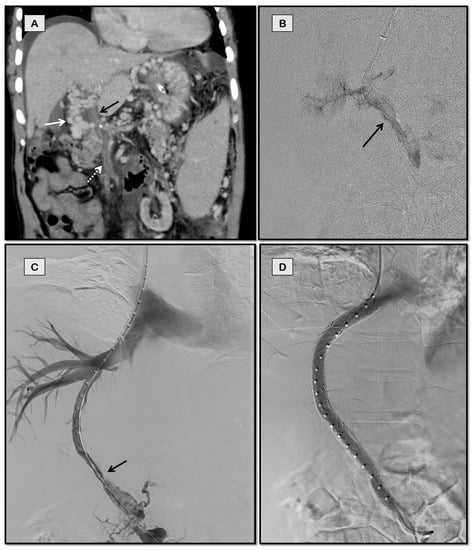

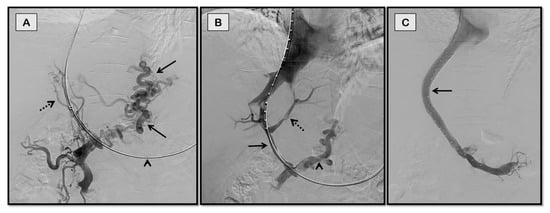

Figure 1. TIPS in a 61-year-old man with polycythemia vera and chronic porto-mesenteric vein thrombosis who presented with recurrent variceal bleed refractory to endoscopic therapy. Patient was not a surgical candidate due to multiple comorbidities. Coronal-oblique image (A) from the computed tomographic (CT) scan of the patient showing chronic thrombosis of the portal vein (black arrow) and superior mesenteric vein (dashed arrow) with cavernoma formation (white arrow). Fluoroscopic spot image (B) shows the thrombosed portal vein (arrow) accessed from jugular approach. Post balloon maceration and thromboaspiration, there is partial recanalization of the portal and superior mesenteric vein (C). Post-stenting (D) image shows brisk flow through the stent with absence of collateralization.

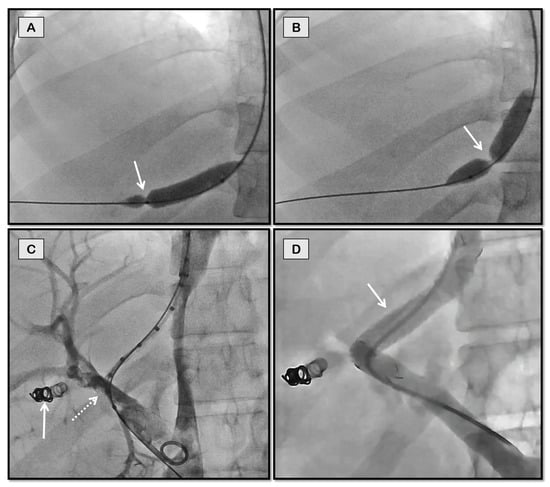

Figure 2. TIPS for recurrent variceal bleeding in a 63-year-old woman with chronic non-cirrhotic portal vein thrombosis. Fluoroscopic spot image (A) shows the partially thrombosed posterior segmental branch of right portal vein (dashed arrow) accessed through jugular approach. Abnormal parenchymal blush is also noted (solid arrow) signifying poor inflow to liver. Superior mesenteric vein angiogram (B,C) showed completely thrombosed portal vein with multiple periportal collaterals (arrows in B) and portal cavernoma (arrows in C). Brisk flow was noted post-stenting (D).

Figure 3. TIPS for refractory ascites in a 53-year-old man with cirrhosis and chronic portal vein thrombosis due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Coronal-oblique CT image (A) shows a large periportal collateral (arrow) replacing the native main portal vein. The main portal vein was accessed through middle hepatic vein via partially patent left portal vein (faintly opacified on B, arrow) from the jugular approach. Image (C) shows the portal cavernoma. Optimal flow of contrast was noted post-stenting (D) with disappearance of collaterals.

2. Transhepatic Approach

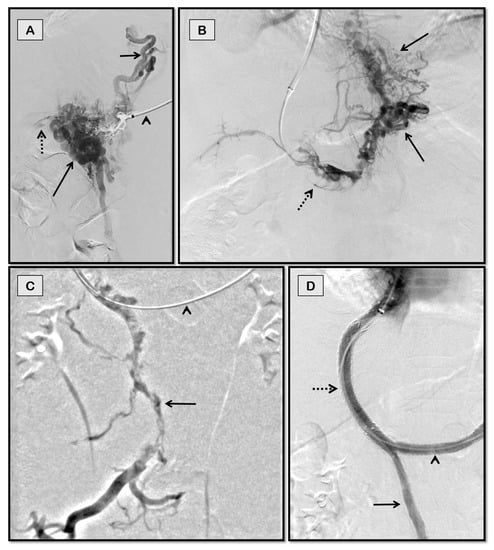

Initial attempts at TIPS in patients with portal vein thrombosis utilized the transhepatic approach [2][14]. Briefly, a micropuncture set is used to access the thrombosed portal vein under fluoroscopic or ultrasound guidance. After balloon dilatation and thrombus aspiration from the portal vein, an inflated contrast-filled balloon or vascular snare is placed, which can be used as a target to puncture the portal vein from the transjugular approach. The rest of the procedure is completed from the jugular side in the standard fashion. The transhepatic tract is plugged with gel foam, coils, or glue. In patients with concomitant chronic thrombosis of hepatic veins (chronic Budd–Chiari Syndrome), this approach can be modified by simultaneously puncturing the thrombosed portal vein and the inferior vena cava (IVC) and snaring the guidewire from IVC through the jugular route (Figure 4).

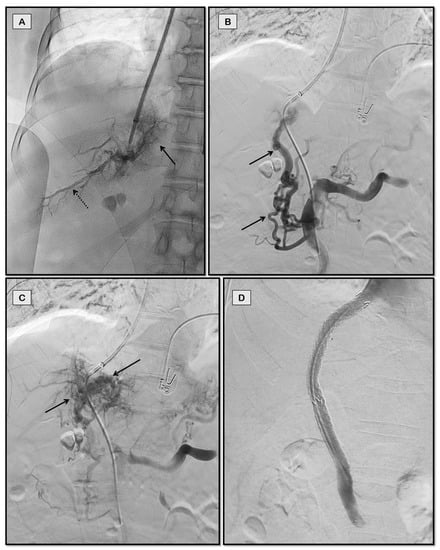

Figure 4. Percutaneous transhepatic access for portosystemic shunting in a 26-year-old man with chronic hepatic and portal vein thrombosis with refractory ascites. Fluoroscopic spot images (A,B) show through-and-through access obtained between percutaneous transhepatic and jugular puncture sites with a balloon inflated to demonstrate the portal puncture site (arrow in A) and IVC puncture site (arrow in B). Post balloon maceration and thromboaspiration (C), there is partial recanalization of the portal vein (dashed arrow). Coils used to close the percutaneous tract can also be seen in this image (solid arrow). Good flow across the stent was noted on the completion angiogram (arrow in D).

The tract between the portal vein and IVC is then balloon dilated, and the portal vein is accessed from the jugular approach to stent deployment. The advantage of the transhepatic approach is that accessing the portal system via this shorter route through the liver under image guidance is considered relatively easier compared to the longer transjugular route wherein a longer needle has to be manipulated through the metallic cannula. However, concern for access site complications remains, especially in patients with coagulopathy and ascites. With the advent of intravascular ultrasound and the trans-splenic approach, the transhepatic route is less commonly utilized.

3. Trans-Splenic Approach

A significant proportion of patients with portal cavernoma do not have a visible native portal vein on imaging. Thus, alternative routes had to be devised for the placement of TIPS. The trans-splenic approach remains the mainstay for such patients. Originally described in the late 1980s, the trans-splenic route was traditionally associated with high rates of hemorrhagic complications [3][18]. However, with improved imaging and real-time ultrasound guidance, complication rates directly attributable to the splenic puncture became low [4][19]. The trans-splenic route is considered ideal when there is a large patent splenic vein with one of its branches entering the splenic parenchyma in a direct anatomic or straight line [5][20]. This intraparenchymal branch is punctured under ultrasound guidance using a micropuncture set. A guidewire and catheter combination are then used to probe and access the fibrotic portal vein via an antegrade approach. The technique requires repeated probing with multiple different catheters at the splenoportal confluence to succeed. After recanalizing the portal vein, a contrast-filled balloon or vascular snare can be placed within the third-order portal vein, which can be targeted via the transjugular route using fluoroscopic triangulation to get the guidewire into the portal vein from the jugular side. This guidewire is snared from the trans-splenic access route to create through-and-through access (Figure 5).

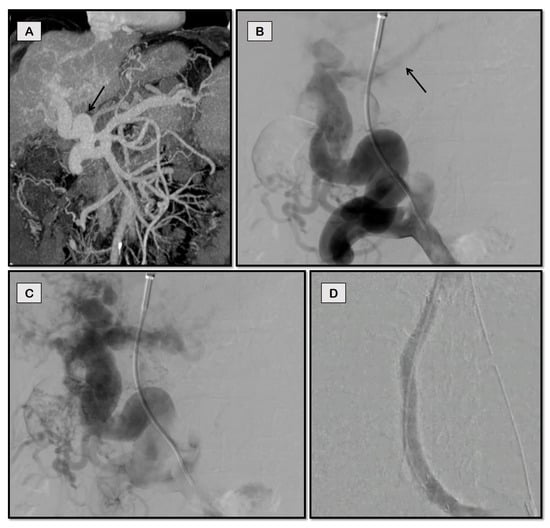

Figure 5. Trans-splenic access for TIPS for recurrent variceal bleeding in a 72-year-old man with chronic portal vein thrombosis secondary to NASH-cirrhosis. Fluoroscopic spot image (A) of splenoportal angiogram obtained after gaining through-and-through access between jugular and trans-splenic puncture sites (arrowhead) shows completely thrombosed portal vein with periportal collaterals (dashed arrow) and tortuous left gastric vein giving rise to esophageal varices (solid arrows). Post balloon maceration and thromboaspiration (B), there is partial recanalization of the main portal vein (solid arrow) and its intrahepatic branches (dashed arrow), but the persistent filling of the left gastric vein (arrowhead). Image (C) shows optimal contrast flow through the TIPS stent with the disappearance of collaterals.

The rest of the procedure is completed via neck using a standard technique. The trans-splenic access site is plugged in to avoid bleeding complications. This approach can also be used in patients with partial thrombosis of the splenic vein at the splenoportal confluence in whom accessing the splenic vein from the transjugular route is difficult (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Trans-splenic TIPS for recurrent variceal bleeding in a 63-year-old man with non-cirrhotic chronic porto-mesenteric and splenic vein thrombosis. Fluoroscopic spot image (A) of angiogram obtained through trans-splenic route (arrowhead) showing tortuous short gastric vein (short arrow) and perisplenic collaterals (long arrow). Splenic vein is faintly opacified (dashed arrow). Venogram images (B,C) captured after obtaining transjugular access through splenic route (arrowhead in C) showing completely thrombosed portal and superior mesenteric veins (dashed arrow in (B) and solid arrow in (C), respectively) with varices (solid arrows in B). Image (D) depicts bifurcated Y-shaped stents in splenoportal axis showing brisk flow with disappearance of collaterals.

4. Transmesenteric Approach

Recent studies have described the percutaneous transmesenteric approach to access the portal vein via the antegrade route [6][7][21,22]. For patients in whom primary transjugular, transhepatic, or trans-splenic approaches fail due to chronically thrombosed splenic veins with non-visualization of intrahepatic native portal vein branches or those who have undergone splenectomy, this route can be utilized. A 21-G needle is used to access the superior or inferior mesenteric vein via the transabdominal route under ultrasound guidance. A guidewire and catheter combination are then used to catheterize the thrombosed portal vein. Post recanalization of the portal vein, a snare is placed within it, which can be used as a target from the transjugular side for access. This guidewire inserted from the jugular route is snared from the percutaneous mesenteric vein entry site to establish Archimedean access. The procedure is thereafter completed via the jugular route using the standard technique.

5. Collateral Vein Stenting

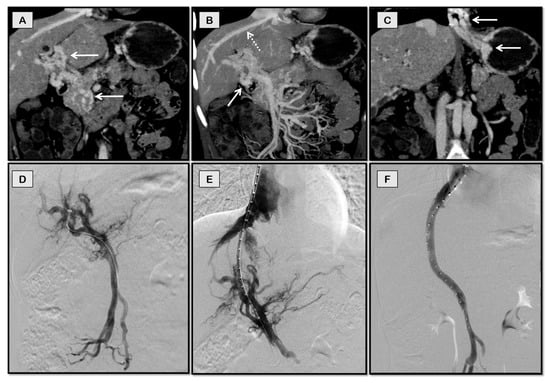

Large, relatively less tortuous periportal collateral veins communicating with the superior mesenteric vein or splenic vein inferiorly can sometimes be used to create TIPS in patients who had a failure of TIPS via other approaches. These collaterals and the possible route through which they can be accessed via any of the three hepatic veins can be evaluated by preprocedural imaging (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 7. TIPS through a collateral vein for recurrent variceal bleeding in a 17-year-old girl with chronic non-cirrhotic portal vein thrombosis. She had undergone a splenectomy at the age of 6 years and was not a candidate for Rex shunt. Coronal-oblique CT images (A–C) showing portal cavernoma (arrows in A), dominant collateral vein (dashed arrow in B) in the same plane as middle hepatic vein (solid arrow in B), and esophageal and gastric varices (arrows in C). The collateral vein was accessed through a jugular route (D) and stented (E) with flow restoration and disappearance of collaterals (F).

Figure 8. TIPS through collateral vein for refractory ascites in a 59-year-old man with chronic portal vein thrombosis secondary to NASH-cirrhosis. Coronal-oblique CT images (A,B) showing portal cavernoma (arrows in A) and dominant collateral vein (solid arrow in B) in the same plane as middle hepatic vein (dashed arrow in B). Collateral vein was accessed through jugular route (C) and stented with restoration of flow (D).

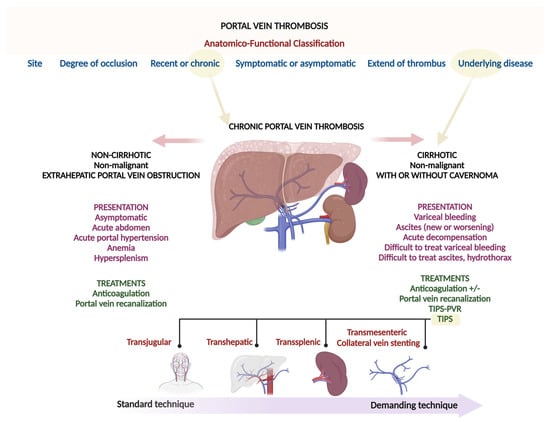

However, accessing a suitable collateral vein is often difficult and risks extrahepatic portal vein laceration and hemoperitoneum. An infographic summary of chronic PVT and its pertinent clinical and therapeutic features is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Summary infographics.