Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Philip Jennings and Version 2 by Camila Xu.

Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) are efficient structures for attracting private investment, increasing the penetration of renewable energy and reducing the cost of electricity for consumers. It is expected that the number of VPPs will increase rapidly as their financial return is attractive to investors. VPPs will provide added value to consumers, to power systems and to electricity markets by contributing to different services such as the energy and load-following services. Grid forming inverters (GFM) are used to connect distributed energy sources and devices into a unique resource and convert it to Alternating Current. GFMs are especially suited to connecting VPPs to the main power grid.

- virtual power plant

- grid-forming inverters

- renewable energy

1. Introduction

Global warming has reached a point where it is causing serious climate change, and this has focused the world’s attention on reducing the use of fossil fuel-based sources to generate electrical power [1]. In addition to this, fossil fuels are being seriously depleted, and some believe that they should be preserved for high-value applications and future generations. As a result, the use of renewable energy sources (RESs) such as solar and wind has experienced a sharp increase in recent years. Initially, large-scale RESs were integrated into distribution networks by utilities with different objectives [2][3][2,3]. For example, the authors of [4] advocated RESs to enhance the power quality of distribution networks. Likewise, reliability enhancement was another application of the integration of RESs into the power distribution grid [5]. From this, it is clear that RESs not only decrease the considerable amount of pollution derived from power generation, but also bring advantages such as loss minimization and reliability improvement.

Similarly, consumers have attempted to reduce their electricity costs and cut their CO2 emissions by installing photovoltaic (PV) panels on their house roofs [6]. Although this mechanism often helps to decrease their electricity bills, there remain some unresolved issues. Firstly, their additional generation may be partially wasted because they cannot participate effectively in the wholesale electricity market, because their generation is not significant enough to allow them to have an active role in the market. Another problem of such standalone systems is that they experience more power outages due to natural disasters, like hurricanes, earthquakes and storms. In order to tackle these problems related to rooftop PV, the concept of a virtual power plant (VPP) has been introduced [7]. Generally speaking, VPP means combining dispersed small-scale generators to create a unified system, resulting in increasing their ability to participate in the wholesale electricity market as well as increasing the stability of the grid. VPPs can be easily formed based on existing systems and they can decrease public expenditure on additional transmission lines.

2. Virtual Power Plants (VPPs)

VPPs are becoming appealing at the present time due to combining dispersed energy resources into a unified power plant which can supply the local demand as well as connecting to the main grids [8][12]. This section investigates the literature related to case studies of virtual power plants (VPPs) and the costing formulation of VPPs, along with the different approaches to bidding strategies for VPPs. After reviewing the case studies on VPPs, the aspects of customer engagement, demand response and gamification are discussed. Then, the components of expenses and revenues of a VPP when participating in an electricity market are presented, followed by a review of different bidding strategy algorithms for VPPs in the electricity market.2.1. General Overview

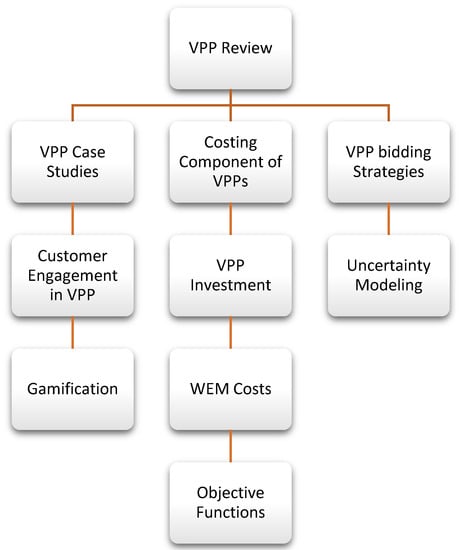

Reducing the carbon footprint and improving the sustainability of energy systems are some of the main goals of many countries. To achieve these goals, many nations are planning for increasing renewable energy integration, for which they have set some targets, such as the contribution of 23.5% renewable generation by 2020 in Australia, which it has already achieved [9][13]. To speed up renewable integration, the governments provide some level of incentives to investors and end-users for the installation and use of renewable-based energy resources, such as photovoltaics (PV) and wind, and also for energy storage [10][14]. Considering the increase in electricity prices in Australia by 200% during the last decade, which brings financial difficulties to many people, it is critical that the use of renewable energy resources and energy storage reduces the cost of electricity for people. Energy aggregators such as VPPs have a great potential to achieve this goal of reduced electricity prices for end-users. VPPs can integrate and coordinate all available energy resources and load flexibility in one place to harmonize the use of energy in order to reduce the cost of electricity by proper planning of energy usage, electricity market participation and customer engagement [11][12][15,16]. To realize all the potential benefits of a VPP, the VPP should be carefully designed and should be managed optimally to be able to produce a profit for the VPP owner and reduce the cost of electricity for the customers [12][13][16,17]. In this rpapesearchr, the previous relevant works and research on VPPs, customer engagement and electricity market participation are discussed, as shown in Figure 1 [14][18].

Figure 1. The components of the literature review in this research.

The components of the literature review in this article.

2.2. VPP Case Studies

There are many studies that investigate different aspects of VPPs. For example, [15][19] evaluates the role of VPPs in encouraging the customers within the VPP to use energy efficient appliances. This study on a 63 MW VPP shows a significant energy reduction of 273 GWh/year when high-efficiency devices are installed [15][19]. The affordability and technical aspects of VPP implementation through multiple revenue streams are discussed for a university campus in [16][20]. This research shows that a VPP within a university can be a successful business case in urban areas for the owner; however, the detailed formulation of the expenses is not provided. A VPP has the ability to coordinate the flexibilities from loads for a larger gain in providing services to an electricity market or grid. The Next Kraftwerke is an example of this capability of VPPs; customers, regardless of their locations, can sign up to participate in this VPP, commit to the program and share the benefits generated by the VPP [17][21]. Also, a VPP can aggregate specific devices such as micro combined heat and power (CHP) modules. For example, in Germany, 25 CHPs are integrated and the effectiveness of that for Germany is investigated in [18][22]. There are several categories of VPPs, including community VPP or commercial VPP. Community VPP generally refers to a coordination of neighbouring residential customers and some community service utilities such as parks and aged care facilities. Practical cases of community VPP exist in Ireland, Belgium and the Netherlands [19][23]. Commercial VPP, on the other hand, coordinates commercial and industrial customers, for example, in a large shopping centre or in an industrial park. A case study of a commercial VPP in Scotland shows that more than a 10% increase in the VPP profit has been achieved by good management of renewables and interaction with the electricity market [20][24]. VPPs can be used to maximise the self-supply, such as the case in Spain, in which the VPP is designed to be as self-sufficient as possible while contributing to the electricity market and local grids [21][25]. In some VPP cases, some economic metric such as gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, unemployment rate, etc., are taken into account to evaluate the benefits of establishing VPPs on different aspects of social, economic and environmental criteria [22][26]. It is observed, for example, that a high level of renewable integration can significantly influence the prices in the electricity market [23][11]. A case study of VPP participation in the electricity market in Germany shows a good economic outcome [24][27]. For example, the revenue of the VPP increased by 11% [24][27]. Also, short-term techno-economic analysis of VPPs has been conducted to evaluate the effect of load dynamics, which cannot be used for the cost–benefit assessment of a VPP [25][28]. Islanded VPPs which are not connected to the grid are also considered as an option for renewable integration but their effectiveness is limited as they do not participate in the electricity market [26][29]. A summary of the comparison of literature topics is provided in Table 1.Table 1.

A comparison of recent papers on VPP case studies. (√: considered, ×: not considered, and #: reference number).

| Ref. # | DR | PVs | Energy Storage | Heat Pump | Electricity Market | Detailed Modelling | Gamified DR | WA Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [15][19] | × | √ | × | × | √ | √ | × | × |

| [16][20] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | × | × |

| [17][21] | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | × | × | × |

| [18][22] | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | × | × | × |

| [19][23] | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | × | × | × |

| [20][24] | × | √ | × | × | √ | √ | × | × |

| [21][25] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | × | × |

| [22][26] | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | × | × | × |

| [23][11] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | × | × |

| [24][27] | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | × | × |

| [25][28] | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | × | × | × |

| [26][29] | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | × | × |

| [27][30] | × | √ | √ | × | × | √ | × | × |

| [28][31] | × | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | × | √ |

-

Participation in the electricity market to provide different services such as energy and ancillary services such as frequency regulation and grid voltage control;

-

Provision of operational visibility for better understanding of VPPs’ benefits;

-

Enhancement of customer satisfaction and experience;

-

Evaluation of the requirement of cyber security.

In WA, in addition to a project in South Lake, two other projects on VPPs are underway. One project is called “Project Symphony”, in which the homes in the suburbs of Harrisdale, Piara Waters and Forrestdale in WA will form a VPP; 50% of homes in these suburbs have rooftop PVs, which contribute to the VPP along with the batteries, and some appliances such as air conditioners and hot water systems. This project, which is supported by Synergy, Western Power and AEMO, is in its early stages and is planned to finish in mid-to-late 2023 [29]. There are no more details about how this project would be implemented. Another project in WA is the “Schools VPP Pilot Project”, in which 17 schools are participating. PVs and batteries will be installed in schools with the goal that the battery can contribute to the reliability and security of local grids while improving the sustainability of energy supply at schools. Based on the available information, there is no WEM participation from these school VPPs, and they are designed to work as a community VPP [28].In WA, in addition to a project in South Lake, two other projects on VPPs are underway. One project is called “Project Symphony”, in which the homes in the suburbs of Harrisdale, Piara Waters and Forrestdale in WA will form a VPP; 50% of homes in these suburbs have rooftop PVs, which contribute to the VPP along with the batteries, and some appliances such as air conditioners and hot water systems. This project, which is supported by Synergy, Western Power and AEMO, is in its early stages and is planned to finish in mid-to-late 2023 [32]. There are no more details about how this project would be implemented. Another project in WA is the “Schools VPP Pilot Project”, in which 17 schools are participating. PVs and batteries will be installed in schools with the goal that the battery can contribute to the reliability and security of local grids while improving the sustainability of energy supply at schools. Based on the available information, there is no WEM participation from these school VPPs, and they are designed to work as a community VPP [31].

2.3. Customer Engagement in VPPs

Customers can be engaged with VPPs in different ways such as controlling their consumption, via air conditioners, hot water systems, pool pumps, smart appliances or actively managing their energy production from solar rooftop PV systems and energy storage. These contributions are usually categorised as demand response (DR), or more generally, customer engagement. To realise these contributions, an active arrangement between customers and the VPP owner should be in place [30][33]. This arrangement will enable the VPP to intervene in energy-related behaviour of customers in order to change it to the required model. One of the effective platforms is smart energy management systems (EMS), which can be configured for engaging customers. EMS includes smart meters, communication, control system, user-friendly dashboard, and the appropriate hardware and software. The inclusion of game design elements into EMS provides a great opportunity for energy-related behaviour change. The gamification approach facilitates active participation and engagement of consumers with the identified values of a VPP [31][34]. Demand response (sometimes called load profile shaping) contributes flexibility. VPPs can use this flexibility to participate in the day-ahead, balancing or ancillary service market in order to maximise their benefit, resulting in reducing the cost of electricity for consumers [32][35]. In a VPP with different sources of energy, both renewable and conventional, and controllable loads, one of the main objectives is to introduce a framework that optimises the response to demand from different signals such as electricity prices, PV generation, temperature, etc. The demand response is generally categorised in two forms as follows [33][36]: (a) load curtailment/turn on and (b) load shift. In the case of load curtailment/turn on, a load can be switched on or off without any requirement for utilising that load again during the timeframe. For example, a pool pump can be turned off for the whole day due to a rise in electricity price. An example of load shift is a washing machine, for which the user of this appliance can shift the use to the defined interval. In addition, considering different types of appliances, the time interval of DR is different. This is usually defined as short-term interval DR or long-term interval DR. For the short-term interval DR, appliances such as electric water heaters (EWH) and air conditioners (AC) are considered to contribute. These or similar appliances can be turned off for a maximum of 10 to 20 min, considering the comfort level of the customer, temperature and all settings from consumers. Where these appliances are interrupted, they will not receive any signal for DR for the next period of time, depending on the settings of consumers, which could be 10 min to 1 h [34][35][37,38]. Long-term interval DR is associated with DR intervals of several hours, for example, 2 h. Appliances such as dishwashers, washing machines, pool pumps, driers, and electric vehicles (EVs) can be programmed to fit into this scheme. Customers will set their requirements for each of these appliances to make sure that their comfort levels are met. For example, they can put constraints on washing machines and dishwashers that the washing cycle should be finished before applying the DR command [36][37][39,40]. In order to facilitate the decision for customers about whether to participate in DR and nominate one or more of their appliances, a framework is necessary to consider the uncertainties in the load, PV, electricity market, cost of load curtailment or shifts for them and time-of-use tariffs (TOUs) [38][41]. Also, the variation of the load profile of customers should be studied by the VPP owner to make sure it satisfies the VPP’s constraints. Some DR loads can be nominated to participate in the electricity market, and some DRs contribute to congestion management of local electric grids. In this case, the grid operator can send a command for controlling these types of loads to stay below the thermal limit of equipment or grid voltage violations [39][42]. Flexible loads can contribute to the operation of VPPs. For example, a VPP with 46% flexible loads was studied to evaluate the effectiveness of DR programs and the comfort levels of the residents [40][43]. Such load flexibilities from VPPs can contribute to the reduction of the peak load and the investment in poles and wires in distribution networks [41][44]. In some cases, customers use combined heat and power generation in order to generate power and heat from the recovery process simultaneously. This technology can be utilised in DR programs to adjust the electricity and heat load together, which can reduce the risk of participation in DR schemes for VPPs if programmed effectively [12][16]. A VPP that includes a CHP should optimise the heat storage and boiler operation in order to effectively participate in a DR program, and then a scheduling decision is provided for participating in the WEM. Although demand responses are considered as one of the sources of flexibilities for VPPs, which potentially could improve the profit of the VPP [42][43][45,46], the problem with traditional DR programs is that they are less effective due to the significant administrative burden or due to violating the comfort level of customers. Gamified DR, on the other hand, will provide a platform for customers to engage in DR programs in enjoyable ways while keeping the level of comfort that they desire.2.4. Gamification

Games are one of the ancient ways of effective learning. People not only can learn through games but also can enjoy the whole process, resulting in the desirable behaviour change for the designed purpose. For effective customer engagement, a behavioural change associated with the use of energy needs to happen in which customers can willingly react and accept the DR commands from the VPP owner. Also, the customers can reject or accept any types of participation in DR programs or program EMS through auto-response to the desirable events. The value created by the gamified DR programs will contribute to the electricity price reduction for the customers, to VPP profit increase and to some services to the WEM and grid. There are some energy-related applications that work based on gamified approaches. The applications that are reviewed in this rpapesearchr are Ecogator, Social Power Game, Makahiki, Power House, Less Energy Empowers You (LEY), Wattsup, enCOMPASS and Funergy [44][47]. These applications can also be used for energy efficiency/saving if programmed properly [31][34]. The EcoGator application can provide energy efficiency advice when a person wants to buy appliances. Also, it can compare two appliances and give insights to the customer about the sustainability of products [44][47]. The app will give the users some points and increase their level of involvement the more they use the functions of the application. Users of the app can also receive and share energy efficiency tips [45][48]. Social Power Game is designed to provide a collaborative platform amongst neighbours so that they can participate in teams for completing a task while receiving points for doing so. This constructive competition amongst teams of neighbours will result in awareness improvement related to energy consumption and realistic energy savings for households while they enjoy the social interaction between neighbours [44][47]. Makahiki is an application for programming any type of gaming platform. For example, a sequence of activities and actions can be designed for evaluating the energy consumption at home or evaluating the DR events to encourage faster and more accurate decision making. The players can earn points by doing certain actions. The app can provide data visualisation on energy consumption and other data [46][49]. The Power House application can read the energy consumption of a home and use it for giving rewards to each user in an online environment. In this platform, neighbours can enhance their social reputation by adjusting their energy-related behaviours [47][50]. Less Energy Empowers You (LEY) is a gaming platform that challenges the users by encouraging them to use energy optimally in order to obtain maximum points. It also provides some quizzes that award additional points if completed by the user [48][51]. Wattsup is a Facebook-based application which provides ranking, rewards and comparison amongst friends on the basis of their energy consumption [49][52]. The enCompass and Funergy are other gamification platforms for energy saving which utilise data collection sensors including user data, data analytics, action recommendations, and a programmable gamification system [50][53]. The collected data can be compared with some reference data or other users’ data to provide some insights to the users about their levels on the ladder and to give some recommendations on the appropriate use of energy [44][51][47,54].3. Concept of a Grid-Forming VPP

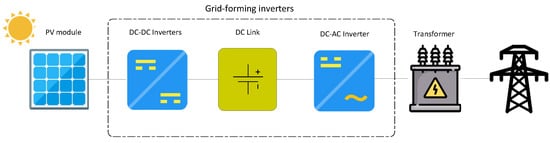

Grid-forming inverters are used to connect dispersed resources into a unique resource and convert it to Alternating Current (AC). The design of a grid-forming inverter is illustrated in Figure 2 [52][94]. As can be seen, the PV modules generate direct current power by receiving energy from the Sun. The generated power may have a low/high level of voltage which can be controlled by DC-DC inverters [53][95]. Then, the regulated voltage from the DC-DC inverters is connected to DC-AC inverters in a DC link [54][96]. Eventually, the AC power is transmitted to the power grid by step-up transformers. This GFM inverter enables us to simultaneously convert DC to AC and inject/absorb reactive power into the network.

Figure 2.

Schematic of grid-forming inverters.

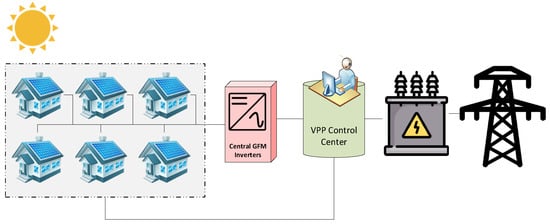

Figure 3.

Schematic of a grid-forming VPP without energy storage.

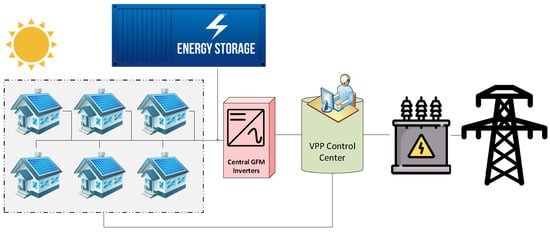

Figure 4.

Schematic of a grid-forming VPP with energy storage.