Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Dean Liu and Version 1 by Ekaterina Mikhailova.

The diverse biological properties of platinum nanoparticles (PtNPs) make them ideal for use in the development of new tools in therapy, diagnostics, and other biomedical purposes. “Green” PtNPs synthesis is of great interest as it is eco-friendly, less energy-consuming and minimizes the amount of toxic by-products.

- platinum nanoparticles

- green synthesis

- capping agents

1. Introduction

Since the end of the 20th century, the popularity of metal nanoparticles has grown from year to year. This is not surprising because they are widely used in various spheres of human activity owing to their many valuable properties. Green technologies—eco-friendly technologies—are of particular importance as they are simple, cheap, practically waste-free and possess the ability to control the resulting nanoparticles characteristics (size, shape, stability), as well as being a popular topic to study in recent years. This is confirmed by the impressive dynamics of the number of publications on this topic that have emerged in the last twenty years. [1]. Different nanoparticles, nanocomposites and nanostructures possessing biocompatibility are of interest for a wide variety of human activity fields: in the food industry, food packaging and the development of functional food products to increase food safety, the detection of food pathogens and extend the shelf life of food products [2], as well as catalysts for biofuels (for example, Cs2O−MgO/MPC nanocomposite was used as the main nanocatalyst for the production of biodiesel from olive oil) [3], application in makeup and skin care [4], and, of course, use in diagnosis, medical treatment, theranostics, and tissue engineering (these are not only metal nanoparticles, but also, for instance, nanostructured CaPs with surface-rich–OH groups and Ca2+ cations, which can effectively adsorb therapeutic agents [5]). Biosynthesis strategies involve using living objects—microorganisms, fungi or plants—as bio-factories for metal nanoparticles production [6,7,8,9][6][7][8][9]. The obtained medicinal products reveal wide application prospects for the biomedical field for combating pathogens of various diseases, the prevention and treatment of oncological diseases, drugs delivery, diagnostic systems, etc.

Although metal nanoparticles such as silver and gold are more well known, the synthesis and analysis of other metal nanoparticles are also gaining momentum [10]. One of these metals is platinum. The Incas were the pioneers of its mining and application, but in the Old World, platinum was unknown until the 16th century. It was first introduced to the conquistadors from South America, and received its name from the Spanish word platina, literally meaning “little silver” according to its external similarity to real silver [11]. Possessing high refractory, platinum was not found worthy of use for a long time, being valued much lower than silver and gold. Between 1889 and 1960, 90% of platinum alloy was used as the international standard for one meter determining. Currently, South Africa and Russia are the leaders in platinum extraction. Platinum is an inert metal, and apparently does not play an important role in the vital activity of living organisms. In addition, this metal is non-toxic in metallic form.

Platinum finds its application in electroplating. It is used as a catalyst in various industries including coating microwave technology elements as well as jewelry. It is used for medical purposes in dentistry, and platinum compounds, cytostatics such as cisplatin, are applied for oncological disease therapy [12,13,14,15][12][13][14][15]. However, drugs such as cisplatin and carboplatin have nephrotoxic, neurotoxic and cytotoxic effects [16]. These effects can be neutralized with the help of green synthesis of platinum nanoparticles and become the key to solving many medical problems. Bio-factories (microorganisms, fungi, plants) are full of various cellular compounds such as proteins, enzymes, acids, etc., important for the characteristic features formation of platinum nanoparticles synthesized in different organisms. The bio-compound importance consists of not only their participation in the nanoparticle’s synthesis, but also the final assembly processes. Having their own remarkable properties, they will be able to multiply the positive effect of platinum nanoparticles use. Moreover, the agenda of “green” technologies, the absence of toxic side effects, and the targeted effect on the human body are still relevant. The present available information about PtNPs antibacterial properties [17], antitumor effects [18], and other potentially beneficial features make them an interesting topic for comprehensive research.

2. Application of Green PtNPs

2.1. Antibacterial Activity

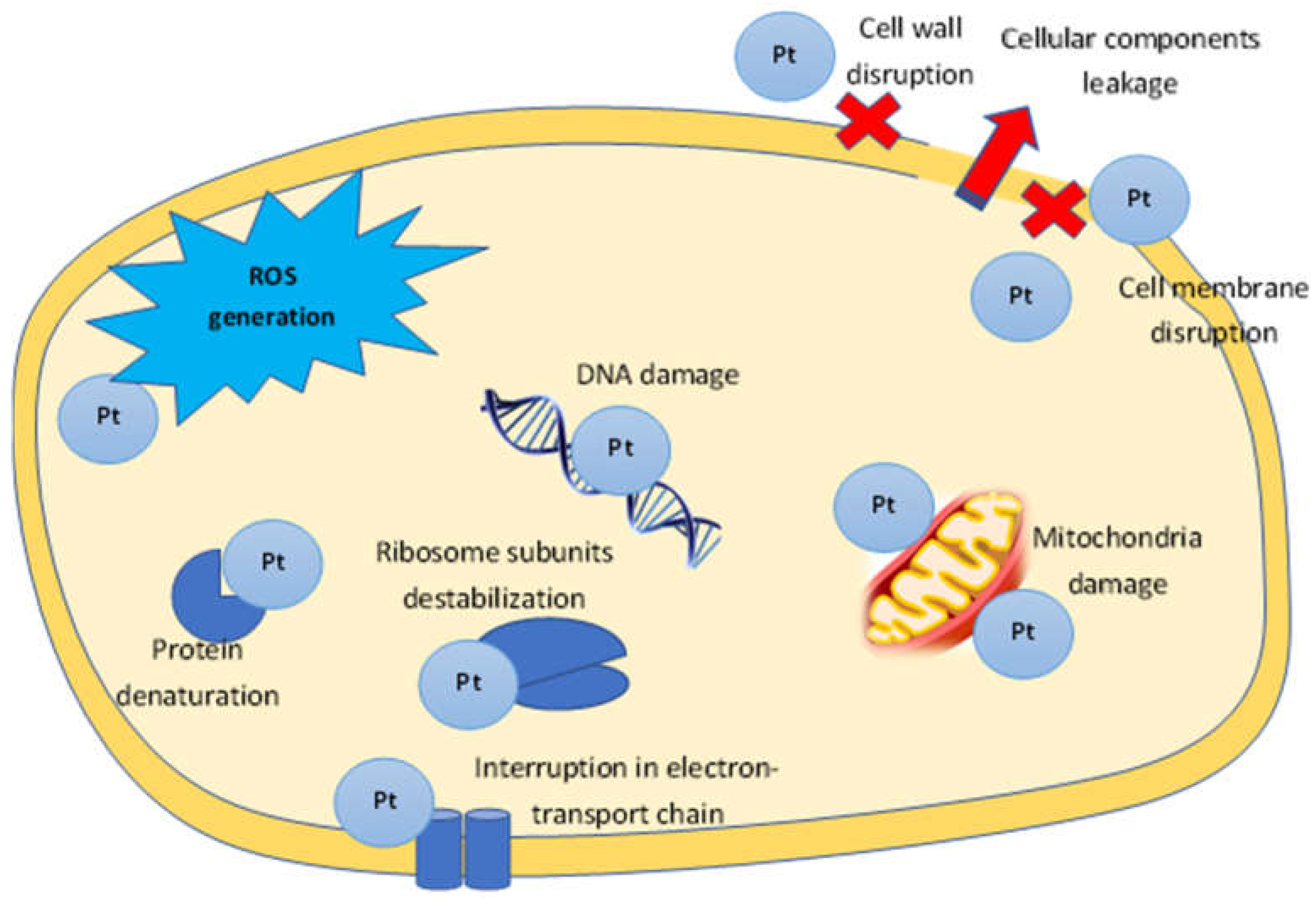

The large-scale application of antibiotics to treat infectious disease has led to the emergence of a large number of pathogen strains resistant to antibiotics causing huge problems in medicine. Biofilms formed by pathogenic microorganisms are a separate issue. Metal nanoparticles are of great value in the solution to this problem, being an effective basis for the development of antimicrobial drugs. The bactericidal properties of metals such as gold and silver have been known to mankind for a long time, and modern methods of nanotechnology discover new possibilities for their use [106,107][19][20]. Metal nanoparticles, including PtNPs, exhibit remarkable biocidal properties against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria [108][21]. Such antimicrobial activity depends on the surface area in contact with microorganisms; their small size and high surface-to-volume ratio gives them the opportunity to interact closely with microbial membranes [107,109][20][22]. The nanoparticle shape also plays an important role in antibacterial activity, and capping agents, due to their own antimicrobial properties, are able to enhance it [110][23]. The mechanisms of nanoparticle action on bacterial cells include: destruction of the microbial cell wall and cell membrane, pump mechanisms damage; destruction of cellular components: ribosome breakdown, inhibition of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) replication and enzyme dysfunction; formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and induction of oxidative stress; and triggering of both congenital and adaptive host immune responses and inhibition of biofilm formation (Figure 1) [20,111][24][25]. Metallic nanoparticles interact with the bacterial cell wall by attraction between the negative charge of the cell wall and the PtNPs positive charge [20,112][24][26]. The main functions of the bacterial cell wall and cell membrane are protection from external influences and the transport of nutrients into and out of the cell. Both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria surface are negatively charged due to the presence of lipoteichoic acid (in Gram-positive) and lipopolysaccharide (in Gram-negatives) [113][27]. The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is a lipid bilayer, whereas the inner membrane is composed of phospholipids. One of the major differences between Gram-positive and Gram-negative is a thicker peptidoglycan layer in the cell wall of Gram-positive, which makes them less vulnerable to metal nanoparticles [114][28]. In addition, the greater nanoparticle efficiency to Gram-negative may be the result of the presence of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) carrying a negative charge, which ensures the PtNPs adhesion to the bacterial cell wall. Due to the presence of the rigid cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria, the antimicrobial activity of Gram-negative bacteria was higher compared to Gram-positive bacteria. Therefore, the biogenic nanoparticles carrying amino groups on their surfaces can attach more effectively to both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial cell walls and destroy them [50][29]. As a result of interaction between PtNPS and the bacterial cell wall, morphological and permeability function changes in the membrane is observed, the integrity of the bacterial cell is disrupted and death occurs [20][24]. In case of PtNPs, their strong negative zeta potential enhances antibacterial activity [110][23].

Figure 1. The proposed mechanism of PtNPs antibacterial activity.

3. Anti-Fungal Activity

There are numerous antifungal drugs, but most of them have many side effects. Green PtNPs represent an alternative in solving this problem. The received data allow uresearchers to characterize them as an effective antifungal agent. Anti-fungal activity was found for Fusarium oxysporum [66][49], and also plant pathogenic fungi such as Colletotrichum acutatum, and Cladosporium fulvum [98][50]. PtNPs prepared using X. strumarium leaves extracts showed significant anti-fungal activity against Candida albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, Aspergillus flaves and A. niger [91][51]. The fungicidal effect of platinum nanoparticles obtained with gum kondagogu was found for A. parasiticus and A. flavus [127][52]. The inhibitory activity of Pt nanocomposite on A. parasiticus and A. flavusfungi is mediated through the induction of oxidative stress, resulting in the formation of ROS and subsequent damage to fungal mycelial morphology and membrane, ultimately leading to cellular damage and fungal growth [127][52].4. Anti-Cancer Activity

Cancer is one of the biggest threats to humanity, occupying second place in terms of mortality. Due to the lack of high-quality diagnosis and treatment in the early disease stages, cancer mortality rates are significantly higher in low- and middle-income than in developed countries. Moreover, most modern drugs targeted at treating cancer have a huge number of adverse effects that can seriously worsen the quality of a patient’s life. Therefore, searching for new, inexpensive drugs possessing a low toxic effect would allow this problem to be solved on a qualitatively new level. Platinum–based anticancer drugs have been known for a long time. One of these is cisplatin, with strong cytotoxic, bactericidal and mutagenic properties. The anticancer activity of cisplatin was discovered back in 1965 by Barnett Rosenberg [128][53]. Its action is based on the ability to form strong specific bonds with DNA that induce chemical damage to DNA bases. However, there are many negative effects of such drugs, including nephrotoxicity, fatigue, emesis, alopecia, peripheral neuropathy, and myelosupression. Platinum nanoparticles can open a new page for cancer treatment. The most promising are PtNPs mediated by plant extracts containing essential oils, acids, alkaloids, phytoncides, which show efficacy in various types of cancers [129][54]. For example, an anti-cancer effect was found for Aloe vera, Catharanthus roseus, hot pepper (Capsicum annuum), tulasi (Ocimum sanctum) and many other medicinal plants [130][55]. The combined effect of platinum nanoparticles, capping by different herbs compounds, could enhance the anti-cancer effect and eliminate the toxic effect of the metal. To create new therapeutic agents against cancer, it is very significant to develop inducers of apoptosis: programmed cell death coordinated by a cascade of interdependent cellular reactions. Moreover, it is the most important process for maintaining homeostasis between cell proliferation and mortality [131][56]. Although the action mechanism of platinum nanoparticles on cancer cells is not fully studied, the basic principles, based on in vitro experiments, can be selected: (a) cell cycle arrest; (b) penetration into the nuclear, nucleus and DNA fragmentation; (c) the level of glutathione; (d) inducing mitochondrial dysfunction; (e) expression of caspases; (f) expression of different proinflammatory cytokines; (g) increasing the level of different enzymes (superoxide dismutase, lactate dehydrogenase etc.); and (h) ROS generation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The proposed mechanism of PtNPs anti-cancer activity.

5. Antioxidant Activity

Reactive oxygen species such as hydroxyl, epoxyl, superoxide, peroxylnitrile, and singlet oxygen generate oxidative stress, leading to the growth of various diseases such as inflammation, atherosclerosis, aging, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders [158][94]. Free radical activity suppression by antioxidants helps to support the immune system and allows it to fight against viruses and other foreign invaders more effectively. An evaluation of the antioxidant properties of PtNPs in vitro, as a rule, is performed by removing DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radicals, as one of the most important and widespread free radicals that can harm human cells [159][95]. DPPH is an uncharged free radical that can accept hydrogen or free electrons to produce a stable diamagnetic molecule, that is why it has long been used to test the free radical scavenging capacity of antioxidants [159,160][95][96]. The antioxidant activity is reflected as a percentage in the DPF absorption or removal [159,160][95][96]. It was shown that antioxidant activity was found to be dose-dependent for PtNPs and may also correlate with the nanoparticle size and the zeta potential, depending on the used “bio-factory” [50,66,68,96,123][29][42][45][49][97]. For example, the smallest nanoparticles produced by gram-negative bacteria showed better antioxidant activity than gram-positive ones [50][29]. In addition, capping agents also seemed to play quite an important role in the PtNPs antioxidant activity [77][31]. It should be noted that platinum nanoparticles synthesized by plants with antioxidant potential are of great importance, because plant compounds can prevent ROS-triggered oxidative damage when the endogenous antioxidant system does not cope independently. Ascorbic acid can be an example, possessing an important antioxidant value in physiological conditions and pro-oxidant in pathological conditions (bacterial infections or cancer) [161][98]. Antioxidant activity data were found for plant-mediated platinum nanoparticles from T. involucrata [95][67], A. halimus [89][46], D. bulbifera [86][99], Salix tetraspeama [87][100] and Cordyceps militaris [100][38]. Antioxidant and neuroprotective activities studies of platinum nanoparticles synthesized by Bacopa monnieri leaf extract showed a decrease in ROS generation and the free radical’s removal, thereby increasing the levels of dopamine, its metabolites, GSH, catalase, SOD, and complex I, and decreasing MDA levels along with enhanced motor activity with MPTP-induced (1-methyl 4-phenyl 1,2,3,6 tetrahydropyridine) neurotoxicity in a model of Parkinson’s disease in Danio fish [85][83]. The obtained data may become a potential option for the fight against Parkinson’s disease. Suppression of reactive oxygen species by means of PtNPs interacting with antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase was shown using Drosophila melanogaster as an in vivo model system. Moreover, platinum nanoparticles interacted with hemocytes without any toxic cell effect and significantly accelerated the wound healing process in a short time [162][101].6. Anti-Diabetic Activity

Diabetes mellitus (diabetes) is one of the most urgent problems faced by mankind, despite the significant amount of well-established diagnosis and treatment methods for this disease. Alpha-amylase and α-glucosidase are known to be key enzymes in carbohydrate metabolism, so their inhibition is one of the most significant strategies for diabetes therapy [163,164][102][103]. In addition, α-glucosidase is also considered as the main enzyme involved in carbohydrate metabolism, catalyzing the cleavage of oligosaccharides and disaccharides into monosaccharides [163,164][102][103]. An amylase inhibitor, jointly with starchy foods, reduces the usual upturn in blood sugar. Amylase inhibitors or starch blockers, including silver and other metal nanoparticles, were proved to prevent the absorption of food starches by organism [163][102]. The anti-diabetic effect was discovered in vitro for PtNPs from P. salicifolium: a mild inhibitory effect against α-amylase and a higher effect against α-glucosidase was exhibited [96][97]. The authors suggested that the antidiabetic effect could be attributed to the direct correlation between the phytoconstituents surrounding PtNPs and α-amylase and/or α- glucosidase inhibitory action, excessive ROS production or imbalanced antioxidant protection mechanisms [96][97]. Furthermore, a significant decrease in glucose levels after PtNPs injection was observed in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats [165][104]. Type 2 Diabetes is characterized by an increase in ROS production level, induced by chronic extracellular hyperglycemia as a result of a violation of the cell redox state, causing the abnormal expression of insulin sensitivity genes [166,167][105][106]. In this regard, the enzyme-like antioxidant properties of platinum nanoparticles to absorb free radicals and decline ROS concentration can promote the diabetes struggle. For instance, under the influence of PtNPs, the induction of the gene expression of the antioxidant enzyme catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and hemoxoigenase, suppression of fasting blood glucose levels and an improvement in the impaired ability to sugar tolerance in obese insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic KK-Ay mice was shown [168][107].7. Anti-Inflammation Activity

ROS overproduction is associated with the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. Antioxidant therapy to solve this problem is possible in the face of platinum nanoparticles. Rehman et al. demonstrated that in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of PtNPs may be attributed to their down regulation of the NFjB signaling pathway in macrophages in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells [169][108]. PtNPs showed direct anti-inflammatory activity in RAW264.7 macrophages through a mechanism involving the intracellular ROS uptake by suppressing lipopolysaccharide-triggered production of proinflammatory mediators, including nitric oxide, tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 [170][109]. The high antioxidant activity of platinum nanoparticles was found in a cavernous malformation cellular model of the human brain [171][110]. PtNPs had a significant neuroprotective effect on the ischemic mouse brain [172][111] and effectively protected keratinocytes from UV-induced inflammation [173][112] and suppressed chronic obstructive lung inflammation provoked by acute cigarette smoking [174][113]. Platinum nanoparticles, alone and in combination with palladium nanoparticles, showed antioxidant activity and weakened aging-related skin pathologies in vivo in mice, without causing morphological abnormalities such as cellular infiltration, fat deposition, or cell damage in mouse skin [175][114]. It was supposed that the catalase activity shown by the nanoparticle combination may be useful in the treatment of vertigo: an acquired pigmentation disorder characterized by H2O2/peroxynitrite-mediated oxidative and nitrative stress in the skin.8. Other Application

Photothermal therapy and radiotherapy. Antitumor chemotherapy has many negative diverse consequences for patients, therefore developing less harmful and cancer-specific strategies is an extremely important task. Photothermal therapy may be the one of the decisions. This non-invasive treatment assumes that PtNPs increase the cellular temperature upon irradiation, causing DNA/RNA damage, membrane rupture, protein denaturation and finally apoptosis [176,177][115][116]. Such photothermal therapy using PtNPs, 5–6 nm in size, induce damage of a selective cellular component and cell death [38,176][115][117]. Polypyrrole-coated iron-platinum nanoparticles were used for photothermal therapy and photoacoustic imaging. In vitro investigation experimentally demonstrated the effectiveness of these NPs in killing cancer cells with NIR laser irradiation. Moreover, the phantom test of PAI used in conjunction with FePt@PPyNPs showed a strong photoacoustic signal [177][116]. Cysteine surface modified FePtNPs can be potential sensitizers for chemoradiotherapy: in vitro NPS FePt-Cys induced ROS, suppressed the antioxidant protein expression and induced cell apoptosis, and also facilitated the chemoradiotherapy effects by activating the caspase system and disrupting DNA damage repair. The drug safety and the synergistic effect with cisplatin and irradiation was confirmed by in vivo studies [178][118]. FePtNPs could potentially be a new strategy for increasing radiation therapy efficiency in cancer cells overexpressing hCtr1 due to enhanced uptake and targeting of mitochondria [179][119]. The synergistic antitumor effect with radiation to eliminate tumors for MFP-FePt-GONCs nanoparticles was determined [180][120]. These nanoparticles improved the radiation effects by activating internal mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis and worsening DNA damage repair. Additionally, they induced ROS release, which suppressed antioxidant protein expression and induced cell apoptosis [180][120]. A combination of PtNPs with irradiation by fast ions effectively enhances the strong, lethal damage to DNA [181][121]. In spite of the data presented above, which were obtained for platinum nanoparticles/nanocomposites synthesized by physicochemical methods, “green” PtNPs may have serious potential in this method. Platinum nanoparticles data obtained by Prosopis farcta fruit extract indicate their stability and biocompatibility for application as a contrast agent in computed tomography as an alternative to low molecular weight agents with toxic effects [153][85]. Catalytic activity. The excellent catalytic activity of “green” PtNPs was shown for removing pharmaceutical products (PhP). The platinum nanoparticles produced via D. vulgaris worked as an effective biocatalyst in the removal of four PHPs classes: ibuprofen, ciprofloxacin, sulfamethoxazole and 17β-estradiol, which are most relevant in the environment [182][122]. It is important to note that only 13% of catalytic activity was lost during recycling, indicating the possibility of bacteriogenic PtNPs reuse for technological development in the pharmaceutical wastewater treatment [182][122]. Detection. Platinum nanoparticles obtained by physicochemical approaches can be used for the detection of DNA, cancer cells, antibiotics, glucose, proteins, bacteria, viruses and antibodies [38,183,184,185,186,187,188,189][117][123][124][125][126][127][128][129]. The peroxidase activity of plant-mediated PtNPs makes it possible to quickly detect Hg ions [190][130], as well as hydrogen peroxide [82][131]. Additionally, PtNPs were successfully used for hydrazine detection in spiked water samples [82][131].References

- Maťatkova, O.; Michailidu, J.; Miskovska, A.; Kolouchova, I.; Masak, J.; Cejkov, A. Antimicrobial properties and applications of metal nanoparticles biosynthesized by green methods. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 58, 107905.

- Singh, T.; Shukla, S.; Kumar, P.; Wahla, V.; Bajpai, V.K.; Rather, I.A. Application of nanotechnology in food science: Perception and overview. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1501.

- Hassan, H.M.A.; Alhumaimess, M.S.; Alsohaimi, I.H.; Essawy, A.A.; Hussein, M.F.; Alshammari, H.M.; Aldosari, O.F. Biogenic-mediated synthesis of the Cs2O−MgO/MPC nanocomposite for biodiesel production from olive oil. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 27811–27822.

- Aziz, Z.A.A.; Mohd-Nasir, H.; Ahmad, A.; Mohd. Setapar, S.H.; Peng, W.L.; Chuo, S.C.; Khatoon, A.; Umar, K.; Yaqoob, A.A.; Mohamad Ibrahim, M.N. Role of Nanotechnology for Design and Development of Cosmeceutical: Application in Makeup and Skin Care. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 739.

- Qi, С.; Musetti, S.; Fu, L.-H.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Huang, L. Biomolecule-assisted green synthesis of nanostructured calcium phosphates and their biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2698.

- Park, T.J.; Lee, K.G.; Lee, S.Y. Advances in microbial biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 521–534.

- Patil, M.P.; Kim, J.-O.; Seo, Y.B.; Kang, M.-j.; Kim, G.-D. Biogenic synthesis of metallic nanoparticles and their antibacterial applications. J. Life Sci. 2021, 31, 862–872.

- Hulkoti, N.I.; Taranath, T.C. Biosynthesis of nanoparticles using microbes—A review. Colloids Surf. B 2014, 121, 474–483.

- Hano, C.; Abbasi, B.H. Plant-Based Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Production, Characterization and Applications. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 31.

- Jadoun, S.; Arif, R.; Jangid, N.K.; Meena, R.K. Green synthesis of nanoparticles using plant extracts: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 355–374.

- McDonald, D.; Hunt, L.B. A History of Platinum and its Allied Metals; Distributed by Europa Publicat; Europa Editions: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 4–5.

- Odularu, A.T.; Ajibade, P.A.; Mbese, J.Z.; Oyedeji, O.O. Developments in Platinum-Group Metals as Dual Antibacterial and Anticancer Agents. J. Chem. 2019, 5459461.

- Barnard, C.F.J. Platinum anti-cancer agents twenty years of continuing development. Platin. Met. Rev. 1989, 33, 162–167.

- Lewis, R. From basic research to cancer drug; the story of cisplatin. Science 2009, 13, 11.

- Wilson, J.J.; Lippard, S.J. Synthetic methods for the preparation of platinum anticancer complexes. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4470–4495.

- Bendale, Y.; Bendale, V.; Paul, S. Evaluation of cytotoxic activity of platinum nanoparticles against normal and cancer cells and its anticancer potential through induction of apoptosis. Integr. Med. Res. 2017, 6, 141–148.

- Vukoja, D.; Vlainic, J.; Ljolic Bilic, V.; Martinaga, L.; Rezic, I.; Brlek Gorski, D.; Kosalec, I. Innovative Insights into In vitro activity of colloidal platinum nanoparticles against ESBL-Producing Strains of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1714.

- Bhattacharya, R.; Mukherjee, P. Biological properties of «naked» metal nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 1289–1306.

- Gu, X.; Xu, Z.; Gu, L.; Xu, H.; Han, F.; Chen, B.; Pan, X. Preparation and antibacterial properties of gold nanoparticles: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 167–187.

- Mikhailova, E.O. Silver nanoparticles: Mechanism of action and probable bio-application. J. Funct. Biomater. 2020, 11, 84.

- Brandelli, A.; Ritter, A.C.; Veras, F.F. Antimicrobial activities of metal nanoparticles. In Metal Nanoparticles in Pharma; Rai, M., Shegokar, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 337–363.

- Franci, G.; Falanga, A.; Galdiero, S.; Palomba, L.; Rai, M.; Morelli, G.; Galdiero, M. Silver nanoparticles as potential antibacterial agents. Molecules 2015, 20, 8856–8874.

- Luzala, M.M.; Muanga, C.K.; Kyana, J.; Safari, J.B.; Zola, E.N.; Mbusa, G.V.; Nuapia, Y.B.; Liesse, J.-M.I.; Nkanga, C.I.; Krause, R.W.M. A critical review of the antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of green-synthesized plant-based metallic nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1841.

- Salem, S.S.; Fouda, A. Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles and Their Prospective Biotechnological Applications: An Overview. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 344–370.

- Chwalibog, A.; Sawosz, E.; Hotowy, A.; Szeliga, J.; Mitura, S.; Mitura, K.; Grodzik, M.; Orlowski, P.; Sokolowska, A. Visualization of interaction between inorganic nanoparticles and bacteria or fungi. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 1085–1094.

- Abalkhil, T.A.; Alharbi, S.A.; Salmen, S.H.; Wainwright, M. Bactericidal activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles against human pathogenic bacteria. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2017, 31, 411–417.

- Feng, Z.V.; Gunsolus, I.L.; Qiu, T.A.; Hurley, K.R.; Nyberg, L.H.; Frew, H.; Johnson, K.P.; Vartanian, A.M.; Jacob, L.M.; Lohse, S.E. Impacts of gold nanoparticle charge and ligand type on surface binding and toxicity to Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 5186–5196.

- Slavin, Y.N.; Asnis, J.; Häfeli, U.O.; Bach, H. Metal nanoparticles: Understanding the mechanisms behind antibacterial activity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 15, 65.

- Eramabadi, P.; Masoudi, M.; Makhdoumi, A.; Mashreghi, M. Microbial cell lysate supernatant (CLS) alteration impact on platinum nanoparticles fabrication, characterization, antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 117, 111292.

- Fanoro, O.T.; Parani, S.; Maluleke, R.; Lebepe, T.C.; Varghese, R.J.; Mgedle, N.; Mavumengwana, V.; Oluwafemi, O.S. Biosynthesis of smaller-sized platinum nanoparticles using the leaf extract of combretum erythrophyllum and its antibacterial activities. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1275.

- Rehman, K.; Khan, S.U.; Tahir, K.; Zaman, U.; Khan, D.; Nazir, S.; Khan, W.U.; Khan, M.I.; Ullah, K.; Anjum, S.I.; et al. Sustainable and green synthesis of novel acid phosphatase mediated platinum nanoparticles (ACP-PtNPs) and investigation of its in vitro antibacterial, antioxidant, hemolysis and photocatalytic activities. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107623.

- Pedone, D.; Moglianetti, M.; De Luca, E.; Bardi, G.; Pompa, P.P. Platinum nanoparticles in nanobiomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4951–4975.

- Subramaniyan, S.B.; Ramani, A.; Ganapathy, V.; Anbazhagan, V. Preparation of self-assembled platinum nanoclusters to combat Salmonella typhi infection and inhibit biofilm formation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 171, 75–84.

- Baptista, P.V.; McCusker, M.P.; Carvalho, A.; Ferreira, D.A.; Mohan, N.M.; Martins, M.; Fernandes, A.R. Nano-strategies to fight multidrug resistant bacteria — “A battle of the titans”. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1441.

- Jan, H.; Gul, R.; Andleeb, A.; Ullah, S.; Shah, M.; Khanum, M.; Ullah, I.; Hano, C.; Abbasi, B.H. A detailed review on biosynthesis of platinum nanoparticles (PtNPs), their potential antimicrobial and biomedical applications. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2021, 25, 101297.

- Nejdl, L.; Kudr, J.; Moulick, A.; Hegerova, D.; Ruttkay-Nedecky, B.; Gumulec, J. Platinum nanoparticles induce damage to DNA and inhibit DNA replication. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180798.

- Sawosz, E.; Chwalibog, A.; Szeliga, J.; Sawosz, F.; Grodzik, M.; Rupiewicz, M. Visualization of gold and platinum nanoparticles interacting with Salmonella Enteritidis and Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 631–637.

- Kumar, M.N.; Govindh, B.; Annapurna, N. Green synthesis and characterization of platinum nanoparticles using Sapindus mukorossi gaertn. fruit pericarp. Asian J. Chem. 2017, 29, 2541–2544.

- Ganaie, U.; Abbasi, T.; Abbasi, S.A. Biomimetic synthesis of platinum nanoparticles utilizing a terrestrial weed Antigonon leptopus. Part. Sci. Technol. 2018, 36, 681–688.

- Jeyapaul, U.; Kala, M.J.; Bosco, A.J.; Piruthiviraj, P.; Easuraja, M. An eco-friendly approach for synthesis of platinum nanoparticles using leaf extracts of Jatropa gossypifolia and Jatropa glandulifera and their antibacterial activity. OJCHEG 2018, 34, 783–790.

- Sharma, K.D. Antibacterial activity of biogenic platinum nanoparticles: An invitro study. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 801–808.

- Gupta, K.; Chundawat, T.S. Bio-inspired synthesis of platinum nanoparticles from fungus Fusarium oxysporum: Its characteristics, potential antimicrobial, antioxidant and photocatalytic activities. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 1050d6.

- Chun, A.L. Green platinum nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2006.

- Ahmed, K.B.A.; Raman, T.; Anbazhagan, V. Platinum nanoparticles inhibit bacteria proliferation and rescue zebrafish from bacterial infection. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 44415–44424.

- Sathiyaraj, G.; Vinosha, M.; Sangeetha, D.; Manikandakrishnan, M.; Palanisamy, S.; Sonaimuthu, M.; Manikandan, R.; You, S.G.; Marimuthu, N. Prabhu Bio-directed synthesis of Pt-nanoparticles from aqueous extract of red algae Halymenia dilatata and their biomedical applications. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 18, 126434.

- Eltaweil, A.S.; Fawzy, M.; Hosny, M.; El-Monaem, E.M.A.; Tamer, T.M.; Omer, A.M. Green synthesis of platinum nanoparticles using Atriplex halimus leaves for potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and catalytic applications. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 103517.

- Muraro, P.C.L.; Anjos, J.F.; Pinheiro, L.D.S.M.; Gomes, P.; Sagrillo, M.R.; da Silva, W.L. Green synthesis, antimicrobial, and antitumor activity of platinum nanoparticles: A review. Disciplinarum Scientia. Série: Naturais e Tecnológicas 2021, 22, 169–178.

- Rajathi, F.A.A.; Nambaru, V.R.M.S. Phytofabrication of nano-crystalline platinum nanoparticles by leaves of Cerbera manghas and its antibacterial efficacy. Int. J. Pharm. Bio. Sci. 2014, 5, 619–628.

- Arya, A.; Gupta, K.; Chundawat, T.S. In Vitro Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of Biogenically Synthesized Palladium and Platinum Nanoparticles Using Botryococcus braunii. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 17, 299–306.

- Velmurugan, P.; Shim, J.; Kim, K.; Oh, B.-T. Prunus yedoensis tree gum mediated synthesis of platinum nanoparticles with antifungal activity against phytopathogens. Mater. Lett. 2016, 174, 61–65.

- Kumar, P.V.; Kala, S.M.J.; Prakash, K.S. Green synthesis derived Pt-nanoparticles using Xanthium strumarium leaf extract and their biological studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103146.

- Godugu, D.; Beedu, S.R. Biopolymer-mediated synthesis and characterisation of platinum nanocomposite and its anti-fungal activity against A. parasiticus and A. flavus. Micro Nano Lett. 2018, 13, 1491–1496.

- Rosenberg, B.; Vancamp, L.; Krigas, T. Inhibition of cell division in Escherichia coli by electrolysis products from a platinum electrode. Nature 1965, 205, 698–699.

- Govind, P. Some important anticancer herbs: A review. IRJP 2011, 2, 45–52.

- Khan, I.; Paul, S.; Jakhar, R.; Bhardwaj, M.; Han, J.; Kang, S.C. Novel quercetin derivative TEF induces ER stress and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in human colon cancer HCT-116 cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 789–799.

- Ullah, S.; Ahmad, A.; Wang, A.; Raza, M.; Jan, A.U.; Tahir, K.; Qipeng, Y. Bio-fabrication of catalytic platinum nanoparticles and their in vitro efficacy against lungs cancer cells line (A549). J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017, 173, 368–375.

- Sahin, B.; Aygün, A.; Gündüz, H.; Sahin, K.; Demir, E.; Akocak, S.; Sen, F. Cytotoxic effects of platinum nanoparticles obtained from pomegranate extract by the green synthesis method on the MCF-7 cell line. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 163, 119–124.

- Alshatwi, A.A.; Periasamy, J.A.; Subbarayan, V. Green synthesis of platinum nanoparticles that induce cell death and G2/M-phase cell cycle arrest in human cervical cancer cells. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2015, 26, 7.

- Gurunathan, S.; Jeyaraj, M.; Kang, M.-H.; Kim, J.-H. Anticancer properties of platinum nanoparticles and retinoic acid: Combination therapy for the treatment of human neuroblastoma cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6792.

- Rokade, S.S.; Joshi, K.A.; Mahajan, K.; Patil, S.; Tomar, G.; Dubal, D.S.; Parihar, V.S.; Kitture, R.; Bellare, J.R.; Ghosh, S. Gloriosa superba mediated synthesis of platinum and palladium nanoparticles for induction of apoptosis in breast cancer. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2018, 2018, 4924186.

- Loan, T.T.; Do, L.T.; Yoo, H. Platinum Nanoparticles Induce Apoptosis on Raw 264.7 Macrophage Cells. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 18, 861–864.

- Rokade, S.S.; Joshi, K.A.; Mahajan, K.; Tomar, G.; Dubal, D.S.; Parihar, V.S.; Kitture, R.; Bellare, J.; Ghosh, S. Novel Anticancer Platinum and Palladium Nanoparticles from Barleria prionitis. Glob J. Nanomed. 2017, 2, 555600.

- Dobrucka, R.; Romaniuk-Drapała, A.; Kaczmarek, V. Evaluation of biological synthesized platinum nanoparticles using Ononidis radix extract on the cell lung carcinoma A549. Biomed. Microdevices 2019, 21, 75.

- Johnstone, T.C.; Park, G.Y.; Lippard, S.J. Understanding and improving platinum anticancer drugs–phenanthriplatin. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 471–476.

- Tait, S.W.G.; Ichim, G.; Green, D.R. Die another way–non-apoptotic mechanisms of cell death. J. Cell. Sci. 2014, 127, 2135–2144.

- Kutwin, M.; Sawosz, E.; Jaworski, S.; Hinzmann, M.; Wierzbicki, M.; Hotowy, A.; Grodzik, M.; Winnicka, A.; Chwalibog, A. Investigation of platinum nanoparticle properties against U87 glioblastoma multiforme. Arch. Med. Sci. 2017, 6, 1322–1334.

- Selvi, A.M.; Palanisamy, S.; Jeyanthi, S.; Vinosh, M.; Mohandoss, S.; Tabars, M.; You, S.G.; Kannapiran, E.; Prabhu, N.M. Synthesis of Tragia involucrata mediated platinum nanoparticles for comprehensive therapeutic applications: Antioxidant, antibacterial and mitochondria-associated apoptosis in HeLa cells. Process Biochem. 2020, 98, 21–33.

- Almeer, R.S.; Ali, D.; Alarifi, S.; Alkahtani, S.; Almansour, M. Green platinum nanoparticles interaction with HEK293 cells: Cellular toxicity, apoptosis, and genetic damage. Dose Response 2018, 16, 1559325818807382.

- Toufektchan, E.; Toledo, F. The guardian of the genome revisited: P53 downregulates genes required for telomere maintenance, DNA repair, and centromere structure. Cancers 2018, 10, 135.

- Yuan, J.; Murrell, G.A.; Trickett, A.; Wang, M.X. Involvement of cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation in the oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in human tendon fibroblasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2003, 1641, 35–41.

- Liu, X.; Kim, C.N.; Yang, J.; Jemmerson, R.; Wang, X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: Requirement for dATP 1317and cytochome c. Cell 1996, 86, 147–157.

- Zhang, S.; Cui, B.; Lai, H.; Liu, G.; Ghia, E.M.; Widhopf, G.F.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, C.C.N.; Chen, L.; Wu, R.; et al. Ovarian cancer stem cells express ROR1, which can be targeted for anti -cancer-stem-cell therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 17266–17271.

- Sathishkumar, M.; Pavagadhi, S.; Mahadevan, A.; Balasubramanian, R. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles and related cytotoxicity evaluation using A549cells. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 114, 232–240.

- Mohammadi, H.; Abedi, A.; Akbarzade, A. Evaluation of synthesized platinum nanoparticles on the MCF-7 and HepG-2 cancer cell lines. Int. Nano Lett. 2013, 3, 28.

- Elsabahy, M.; Wooley, K. LCytokines as biomarkers of nanoparticle immunotoxicity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5552–5576.

- Gurunathan, S.; Jeyaraj, M.; Kang, M.-H.; Kim, J.-H. The effects of apigenin-biosynthesized ultra-small platinum nanoparticles on the human monocytic THP-1 cell line. Cells 2019, 8, 444.

- Abed, A.; Derakhshan, M.; Karimi, M.; Shirazinia, M.; Mahjoubin-Tehran, M.; Homayonfal, M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Mirzaei, S.A.; Soleimanpour, H.; Dehghani, S.; et al. Platinum nanoparticles in biomedicine: Preparation, anti-cancer activity, and drug delivery vehicles. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 797804.

- Fruehauf, J.P.; Meyskens, F.L. Reactive oxygen species: A breath of life or death? Clin. Cancer Res. O. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 789–794.

- Corbalan, J.J.; Medina, C.; Jacoby, A.; Malinski, T.; Radomski, M.W. Amorphous silica nanoparticles trigger nitric oxide/peroxynitrite imbalance in human endothelial cells: Inflammatory and cytotoxic effects. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 2821.

- Uehara, T.; Kikuchi, Y.; Nomura, Y. Caspase activation accompanying cytochrome c release from mitochondria is possibly involved in nitric oxide-induced neuronal apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. J. Neurochem. 1999, 72, 196–205.

- Bolaños, J.P.; Almeida, A.; Stewart, V.; Peuchen, S.; Land, J.M.; Clark, J.B.; Heales, S.J. Nitric oxide-mediated mitochondrial damage in the brain: Mechanisms and implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J. Neurochem. 1997, 68, 2227–2240.

- Roussel, B.D.; Kruppa, A.J.; Miranda, E.; Crowther, D.C.; Lomas, D.A.; Marciniak, S.J. Endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction in neurological disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 105–118.

- Nellore, J.; Pauline, C.; Amarnath, K. Bacopa monnieri Phytochemicals Mediated Synthesis of Platinum Nanoparticles and Its Neurorescue Effect on 1-Methyl 4-Phenyl 1,2,3,6 Tetrahydropyridine-Induced Experimental Parkinsonism in Zebrafish. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 2013, 2013, 1–8.

- Aygun, A.; Gülbagca, F.; Ozer, L.Y.; Ustaoglu, B.; Altunoglu, Y.C.; Baloglu, M.C.; Atalar, M.N.; Alma, M.H.; Sen, F. Biogenic platinum nanoparticles using black cumin seed and their potential usages antimicrobial and anticancer agent. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 179, 1–8.

- Jameel, M.S.; Aziz, A.A.; Baharak, M.A.D.; Mehrdel, B.; Khaniabadi, P.M. Rapid sonochemically-assisted green synthesis of highly stable and biocompatible platinum nanoparticles. Surf. Interfaces. 2020, 20, 100635.

- Baskaran, B.; Muthukumarasamy, A.; Chidambaram, S.; Sugumaran, A.; Ramachandran, K.; Manimuthu, T.R. Cytotoxic potentials of biologically fabricated platinum nanoparticles from Streptomyces sp. on MCF-7 breast cancer cells. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 11, 241–246.

- Gholami-Shabani, M.; Shams-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Gholami-Shabani, Z.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Riazi, G.; Razzaghi-Abyaneh, M. Biogenic approach using sheep milk for the synthesis of platinum nanoparticles: The role of milk protein in platinum reduction and stabilization. Int. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2016, 12, 199–206.

- Jha, B.; Rao, M.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Prasad, K.; Jha, A.K. Punica granatum fabricated platinum nanoparticles: A therapeutic pill for breast cancer. AIP Conf. Proc. 1953, 2018, 030087.

- Al-Radadi, N.S. Green synthesis of platinum nanoparticles using Saudi’s Dates extract and their usage on the cancer cell treatment. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 330–349.

- Bhattacharya, S.; Halder, M.; Sarkar, A.; Pal, P.; Das, A.; Kundu, S.; Mandal, D.; Bhattacharjee, S. Investigating in vitro and in vivo anti-tumor activity of Curvularia-based platinum nanoparticles. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2022, 41, 13–32.

- Wang, D.-P.; Shen, J.; Qin, C.-Y.; Li, Y.-M.; Gao, L.-J.; Zheng, J.; Feng, Y.-L.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Cao, J.-M. Platinum nanoparticles promote breast cancer cell metastasis by disrupting endothelial barrier and inducing intravasation and extravasation. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 7366–7377.

- Borse, V.; Kaler, A.; Banerjee, U.C. Microbial Synthesis of Platinum Nanoparticles and Evaluation of Their Anticancer Activity. J. Emerg. Trends Electr. Electron. 2015, 11, 26–31.

- Biosynthesized Platinum Nanoparticles Inhibit the Proliferation of Human Lung-Cancer Cells in vitro and Delay the Growth of a Human Lung-Tumor Xenograft in vivo -In vitro and in vivo Anticancer Activity of bio-Pt NPs- Yogesh Bendale*, Vineeta Bendale, Rammesh Natu, Saili Paul. J. Pharmacopunct. 2016, 19, 114–121.

- Singh, A.; Kukreti, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S. Oxidative stress: A key modulator in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 2019, 24, 1583.

- Kedare, S.B.; Singh, R. Genesis and development of DPPH method of antioxidant assay. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 412–422.

- Nakkala, J.R.; Mata, R.; Sadras, S.R. The antioxidant and catalytic activities of green synthesized gold nanoparticles from Piper longum fruit extract. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2016, 100, 288–294.

- Hosny, M.; Fawzy, M.; El-Fakharany, E.M.; Omer, A.M.; El-Monaem, E.M.A.; Randa, E. Khalifa, Abdelazeem S. Eltaweil Biogenic synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antidiabetic, and catalytic applications of platinum nanoparticles synthesized from Polygonum salicifolium leaves. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 106806.

- Chakraborthy, A.; Ramani, P.; Sherlin, H.; Premkumar, P.; Natesan, A. Antioxidant and pro-oxidant activity of Vitamin C in oral environment. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2014, 25, 499.

- Ghosh, S.; Nitnavare, R.; Dewle, A.; Tomar, G.B.; Chippalkatti, R.; More, P.; Chopade, B.A. Novel platinum–palladium bimetallic nanoparticles synthesized by Dioscorea bulbifera: Anticancer and antioxidant activities. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 7477–7490.

- Fahmy, S.A.; Fawzy, I.M.; Saleh, B.M.; Issa, M.Y.; Bakowsky, U.; Azzazy, H.M.E.-S. Green Synthesis of Platinum and Palladium Nanoparticles Using Peganum harmala L. Seed Alkaloids: Biological and Computational Studies. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 965.

- Rajaram, K.; Aiswarya, D.; Sureshkumar, P. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticle using Tephrosia tinctoria and its antidiabetic activity. Mater. Lett. 2015, 138, 251–254.

- Chen, G.; Guo, M. Rapid screening for α-glucosidase inhibitors from Gymnema sylvestre by affinity ultrafiltration–HPLC-MS. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 228.

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gu, J.; Chen, S. Biosynthesis of polyphenol-stabilised nanoparticles and assessment of anti-diabetic activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2017, 169, 96–100.

- Bag, J.; Mukherjee, S.; Tripathy, M. Platinum as a novel nanoparticle for wound healing model in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Clust. Sci. 2022.

- Tangvarasittichai, S. Oxidative stress, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 456–480.

- Rovira-Llopis, S.; Bañuls, C.; Diaz-Morales, N.; Hernandez-Mijares, A.; Rocha, M.; Victor, V.M. Mitochondrial dynamics in type 2 diabetes: Pathophysiological implications. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 637–645.

- Shirahata, S.; Hamasaki, T.; Haramaki, K.; Nakamura, T.; Abe, M.; Yan, H.; Kinjo, T.; Nakamichi, N.; Kabayama, S.; Shirahata, K.T. Anti-diabetes effect of water containing hydrogen molecule and Pt nanoparticles. BMC Proc. 2011, 5, P18.

- Ur Rehma, M.; Yoshihisa, Y.; Miyamoto, Y.; Shimizu, T. The anti-inflammatory effects of platinum nanoparticles on the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Inflamm. Res. 2012, 61, 1177–1185.

- Zhu, S.; Zeng, M.; Feng, G.; Wu, H. Platinum nanoparticles as a therapeutic agent against dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 8361–8378.

- Moglianetti, M.; Luca, E.D.; Pedone, D.; Marotta, R.; Pompa, P.P. Platinum nanozymes recover cellular ros homeostasis in oxidative stressmediated disease model. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 3739–3752.

- Takamiya, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Yamashita, T.; Deguchi, K.; Ohta, Y.; Abe, K. Strong neuroprotection with a novel platinum nanoparticle against ischemic Stroke- and tissue plasminogen activator-related brain damages in mice. Neuroscience 2012, 221, 47–55.

- Yoshihisa, Y.; Honda, A.; Zhao, Q.-L.; Makino, T.; Abe, R.; Matsui, K. Protective effects of platinum nanoparticles against UV-light-induced epidermal inflammation. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, 1000–1006.

- Onizawa, S.; Aoshiba, K.; Kajita, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Nagai, A. Platinum nanoparticle antioxidants inhibit pulmonary inflammation in mice exposed to cigarette smoke. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 22, 340–349.

- Shibuya, S.; Ozawa, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Izuo, N.; Toda, T. Palladium and platinum nanoparticles attenuate aging-like skin atrophy via antioxidant activity in mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109288.

- Gharibshahi, E.; Saion, E. Influence of dose on particle size and optical properties of colloidal platinum nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 14723–14741.

- Phan, T.T.V.; Bui, N.Q.; Moorthy, M.S.; Lee, K.D.; Oh, J. Synthesis and in vitro performance of polypyrrole-coated iron-platinum nanoparticles for photothermal therapy and photoacoustic imaging. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 570.

- Gautam, A.; Guleria, P.; Kumar, V. Platinum nanoparticles: Synthesis strategies and applications. Nanoarchitectonics 2020, 1, 70–86.

- Sun, Y.; Miao, H.; Ma, S.; Zhang, L.; You, C.; Tang, F.; Yang, C.; Tian, X.; Wang, F.; Luo, Y.; et al. FePt-Cys nanoparticles induce ROS-dependent cell toxicity, and enhance chemo-radiation sensitivity of NSCLC cells in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Lett. 2018, 418, 27–40.

- Tsai, T.L.; Lai, Y.H.; Hw Chen, H.; Su, W.C. Overcoming radiation resistance by iron-platinum metal alloy nanoparticles in human copper transport 1-overexpressing cancer cells via mitochondrial disturbance. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 2071–2085.

- Peng, S.; Sun, Y.; Luo, Y.; Ma, S.; Sun, W.; Tang, G.; Li, S.; Zhang, N.; Ren, J.; Xiao, Y.; et al. MFP-FePt-GO nanocomposites promote radiosensitivity of non-small cell lung cancer via activating mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis and impairing DNA damage repair. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 2145–2158.

- Porcel, E.; Liehn, S.; Remita, H.; Usami, N.; Koayashi, K.; Furusawa, Y.; Lesech, C.; Lacombe, S. Platinum nanoparticles: A promising material for future cancer therapy? Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 085103.

- Martins, M.; Mourato, C.; Sanches, S.; Noronha, J.P.; Crespo, M.T.; Pereira, I.A. Biogenic platinum and palladium nanoparticles as new catalysts for the removal of pharmaceutical compounds. Water Res. 2016, 108, 160–168.

- Zhang, L.N.; Deng, H.H.; Lin, F.L.; Xu, X.W.; Weng, S.H.; Liu, A.L.; Lin, X.H.; Xia, X.H.; Chen, W. In situ growth of porous platinum nanoparticles on graphene oxide for colorimetric detection of cancer cells. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 2711–2718.

- Chen, T.; Cheng, Z.; Yi, C.; Xu, Z. Synthesis of platinum nanoparticles templated by dendrimers terminated with alkyl chain. Chem. Comm. J. 2018, 54, 9143–9146.

- Kwon, D.; Lee, W.; Kim, W.; Yoo, H.; Shin, H.C.; Jeon, S. Colorimetric detection of penicillin antibiotic residues in pork using hybrid magnetic nanoparticles and penicillin class-selective, antibody-functionalized platinum nanoparticles. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 7639–7645.

- Ji, X.; Lau, H.Y.; Ren, X.; Peng, B.; Zhai, P.; Feng, S.P.; Chan, P.K. Highly sensitive metabolite biosensor based on organic electrochemical transistor integrated with microfluidic channel and poly (N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) capped platinum nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2016, 1, 1600042.

- Yang, Z.H.; Zhuo, Y.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y.Q. A nanohybrid of platinum nanoparticles-porous ZnO-hemin with electrocatalytic activity to construct an amplified immunosensor for detection of influenza. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 78, 321–327.

- Dutta, G.; Nagarajan, S.; Lapidus, L.J.; Lillehoj, P.B. Enzyme-free electrochemical immunosensor based on methylene blue and the electro-oxidation of hydrazine on Pt nanoparticles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 92, 372–377.

- Gao, Z.; Xu, M.; Hou, L.; Chen, G.; Tang, D. Irregular-shaped platinum nanoparticles as peroxidase mimics for highly efficient colorimetric immunoassay. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2013, 776, 79–86.

- Kora, A.J.; Rastogi, L. Peroxidase activity of biogenic platinumnanoparticles: A colorimetric probe towards selective detection of mercuric ions in water samples. Sens. Actuat B 2018, 254, 690–700.

- Karthik, R.; Sasikumar, R.; Chen, S.-M.; Govindasamy, M.; Kumar, J.V.; Muthuraj, V. Green Synthesis of Platinum Nanoparticles Using Quercus Glauca Extract and Its Electrochemical Oxidation of Hydrazine in Water Samples. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016, 11, 8245–8255.

More